This is my wedding photo from 1963. My mother, Olga Munkova, nee Nachodova, is standing on the left, beside her Nanicka - my nanny, then my wife, Alena Munkova, nee Synkova, I, my wife's stepmother, my nephew Jiri Kovanic, my sister Helena Kovanicova, nee Munkova, and her husband Rudolf Kovanic.

In 1959 I met my wife. After the war, many Jews who had returned from the concentration camps married non-Jewish girls. For one, there weren't enough Jewish girls, and also Jews apparently didn't want to have anything to do with their origin any more. My wife and I were an exception. Initially we didn't know that we had a common past. We had both been in Terezin at the same time, but hadn't known of each other. My wife had been in a 'Kinderheim.' When we met, sometime around 1959, and found out that we both had a similar history, it made us very close. People who hadn't experienced what Jews had during the war were after all somewhat distant, because they couldn't understand how we felt. I had never talked about my experiences anywhere. We tried to suppress our feelings and forget about them, and as a couple it was simpler.

My wife comes from Letna. Though her father was a dentist, her ancestors' family tradition was connected with book publishing. Her grandfather was the first publisher of Schweik and founded the Synek publishing house, which before the war had been known for publishing quality books. My wife's mother died of cancer when my wife was still a baby, and her father then found a new wife. Shortly thereafter they registered my wife as a Catholic in the assumption that it would help her in life, but unfortunately during the war entirely different points of view were decisive.

My wife was one of two children. Her brother, Jiri Synek, later known under the pseudonym Frantisek Listopad, who today lives in Lisbon, had a very interesting fate during the war. Back then he was about 18 or twenty years old, and was involved in some underground organization, which is why he hid out with various people in Prague during the entire course of the war. It's unbelievable that no one discovered him, and he must undoubtedly have been very brave. He used to tell stories about how for example he had to steal a rubber stamp in some government office, so he could then use it to stamp some documents. After the war he got an award for courage from President Benes.

He was the only Communist in our family, but a Communist of a different type than were those that during the Communist era bowed down before the regime. Before the putsch in 1948, my wife's brother had gone to France on a business trip, where he then published some political magazine. When after the putsch the Communists summoned him back to Czechoslovakia, he refused to return and stayed abroad.

My wife then had many troubles due to him, they used to take her in to the StB, because her brother occasionally broadcast on Radio Free Europe, which in the 1950s was no joke. It was all carefully noted in their cadre files. Because from the regime's point of view, a Communist who emigrated was much worse than a non-Communist. My wife's brother devoted himself mainly to literature, he's a well-known poet, writer and playwright. He currently lives in Portugal, and is very respected there as a cultural authority. He even represented Portugal in negotiations regarding the Czech Republic joining the European Union. He's received many decorations and awards in Portugal as well as the Czech Republic, most recently for example an award from President Havel as well as the Czech foreign minister for promoting Czech culture in Portugal.

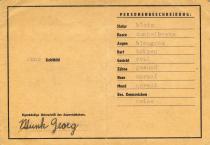

Jiri Munk's wedding

Share

Photos from this interviewee

The Centropa Collection at USHMM

The Centropa archive has been acquired by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

USHMM will soon offer a Special Collections page for Centropa.

Academics please note: USHMM can provide you with original language word-for-word transcripts and high resolution photographs. All publications should be credited: "From the Centropa Collection at the United States Memorial Museum in Washington, DC". Please contact collection [at] centropa.org.