Vienna

Austria

Interviewer: Tanja Eckstein

Date of interview: March 2003

Heinz Bischitz lives in a house owned by the Jewish Community in Vienna’s 2nd district.

I had already asked him six months ago to give me an interview, which he rejected after some consideration.

That’s why I was very surprised when I found out from ESRA that he was indeed ready to give me an interview.

Heinz Bischitz is a large, strong man with a full head of hair.

He comes across as very calm and well-balanced – an impression made stronger by his pipe smoking.

- My Family History

My paternal grandfather was named Moritz Bischitz. He was born in Mattersburg in around 1870 [born on 9 March 1872; Source: DÖW Database] and was a traditional Jew. German was his mother tongue. I assume he was in the Austro-Hungarian Army, but, strangely, no one ever spoke about that.

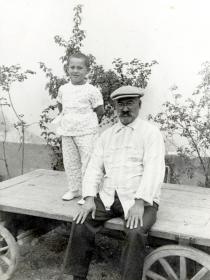

Grandfather trained as a master carpenter and worked as a patternmaker. He had a handlebar mustache, smoked a long pipe, and I can remember that his carpentry workshop always smelled of glue. I believe my grandfather worked in the workshop alone – I never saw employees. He was a patternmaker, and what he did was almost like artistic carving. He also specialized in molds for the industry – that was precision work.

Grandfather had siblings – two or three brothers and sisters who didn’t survive the war. I might have had contact with them when I was very young, but I can’t remember anything about that. I don’t even know what their names were.

My paternal grandmother was called Caroline Bischitz, née Glaser. She was born in Schottwien, but I don’t know when [born on 10 January 1879; Source DÖW Database]. Schottwien is located between Vienna and Semmering. Grandmother was a fairly large, powerful woman.

She had a sister, Johanna Glaser. Both were killed in Theresienstadt. The sisters and my grandfather Moritz were deported together from Vienna to Theresienstadt on 28 July 1942. Johanna Glaser died in Theresienstadt one month later, on 28 August 1942. Caroline and Mortiz Bischitz were then deported from Thereseinstadt to the death camp Treblinka and murdered there. [Source: DÖW Database].

Grandmother’s brothers were called Mortiz Glaser and Bernhard Glaser. In 1938 they both immigrated to Argentina with their families and never returned to Austria.

Until 1938 my grandparents lived in Teesdorf with their daughter, Martha, and son-in-law, Leo Lichtblau. They lived in a large house. There was a shop in the front and an apartment in the back with a garden and my grandfather’s workshop. It was very dark inside.

In 1938 my grandparents needed to relocate to Vienna where they lived in the 2nd district until they were deported to Theresienstadt and murdered.

My grandparents had two sons and a daughter. My father was called Fritz Bischitz and was born in 1904 in Mattersburg. He was the eldest of his siblings. My father was a traditional Jew. He went to temple on the High Holidays and fasted on Yom Kippur.

My uncle had a Hungarian name; he was called Geza Bischitz. He was born around 1908/1909 and was married to Gisela Tichler. They had a son, Peter, who was born in 1935. My aunt and uncle had a village store in Traisen – that’s in Lower Austria – until 1938.

You could buy everything there, as was common back then. In 1938 they immigrated to England and never came back to Austria. My Uncle Geza and Aunt Gisela had a little shop in London after the war. My Cousin Peter lives in London.

My aunt and uncle have been dead for a while. I am in touch with my cousin. He comes to Vienna fairly often. Two years ago he visited the family’s former maid in St. Pölten and they spoke about old times. She is very old, but could still remember him.

We often visited my grandparents, my Aunt Martha – my father’s sister – and Uncle Leo. We lived in Ober Waltersdorf. Aunt Martha was two villages away in Teesdorf, and Traisen is also fairly close-by. Back then I would take everything apart; I was repairing things, so to speak. That’s why my grandmother always gave me an old alarm clock to “repair” for my birthday. It always made me very happy.

My father and his sisters had always maintained contact, just not during the war. My Cousin Peter had three sons; they all live in England. The eldest is called Keith, the middle one is called Ian, and the youngest is Neil. The cousins and the children of the cousins are still in touch.

Aunt Martha Lichtblau, née Bischitz, was my father’s sister. She was married to Leo Lichtblau. Martha and Leo were both trained tailors. Their daughter, Susi, was born in 1933; sadly she passed away last year. My uncle and Aunt also owned a village store in Teesdorf.

In 1938 they immigrated to England and stayed there after the war. After the war my aunt and uncle owned a drugstore in London. My Cousin Susi had two sons: Rufus and Giles. They live in London, but we don’t have much contact with them.

My maternal grandfather was called Armin Knöpfler. As far as I know, he was born in Budapest in 1870. His mother tongue was Hungarian. He was a merchant by trade. In which branch, I don’t know. It had something to do with textiles, I assume. I suppose he served in the Hungarian part of the Austro-Hungarian army. He must have had brothers and sisters, but I didn’t know any of them.

I assume my grandmother, Maria Knöpfler, née Fleischer, was born in Budapest – in Hungary in any case. Her mother tongue was Hungarian. She was a religious woman. Grandmother mostly wore a headscarf – my mother thought her mother would have worn a wig. It was probably taken for granted and no one spoke about it. I don’t recall any siblings.

My grandparents were religious, but they didn’t keep a kosher house because they lived with their daughter, Magda, who was married to a Christian. They observed Shabbat and, for as long as they could, lit candles every Friday. My grandfather also went to the synagogue every Shabbat. They synagogue – a great, big synagogue, not a prayer house – was close to the apartment.

I can still remember the Seder evenings with my grandparents very well, and also that they never ended. My grandfather would go through all the prayers - from A to Z – so the entire Haggadah. Eating would be constantly interrupted in order to keep praying. He did everything as written in the Haggadah – no comma or period would be left out.

I visited my grandfather a few times after the war; he mostly just sat in the kitchen and smoked a long pipe. Both of my grandfathers smoked long pipes, and both of them wore the same mustache. Before the war, Grandfather Knöpfler would visit us every summer in Ober Waltersdorf for a few weeks.

My grandparents survived the Holocaust in Budapest, hidden by their daughter, Magda, and her Christian husband. My grandmother died in 1947 or 48, and my grandfather in 1949 or 50 in Budapest – just a few years after the war. There was already communism in Hungary, and my mother wasn’t allowed to go the funeral; they wouldn’t let her in.

My grandparents had six children. My mother was born Irene Knöpfler in Nitra on 23 January 1906. Nitra is in Slovakia today. When and why the family moved from Nitra to Budapest, I don’t know. My mother was a trained seamstress. She was very consciously Jewish, but she never kept a kosher home, nor did we celebrate Shabbat. On holidays my parents would go to Baden or Vienna.

My mother’s eldest sister was Aunt Ilona Knöpfler. I think she was born in 1898. She never married and always lived with us – therefore I had two mothers. She was in charge of the household, since my mother was always working. We immigrated to Hungary together, then we went to Vienna together, and then to Argentina. She died on 5 June 1967 in Buenos Aires.

My uncle, Manfred Knöpfler, was born in 1901. He was married to a Christian; this unfortunately didn’t help him in the Holocaust – he was deported anyway. He had a son, Georg, who is still living in Budapest.

Aunt Magda Joo, née Knöpfler, was married to Oszkar Joo. He wasn’t Jewish and worked as a chauffeur for the Japanese Embassy during the war. I don’t know where he was working before the war. They had a son, Alexander.

My mother’s youngest sister was always called Nuschi. I don’t know what her actual name was. She was married to Manfred Schlanger. He was a Jew and they had two children: Kathalina and Karoly. Manfred Schlanger was a merchant, but I don’t recall in which industry. They survived the Holocaust in hiding in Budapest.

Anton Knöpfler, my mother’s youngest brother, was born on 12 December 1912. He had a commercial profession. He was a very athletic man. He was deported to a concentration camp and survived with a weight of 32 kilos. After the war he married a Belgium woman and emigrated from Budapest to Belgium a few months after the war. He died relatively young in the 1960s.

My paternal and maternal grandparents got along well and would visit each other for as long as they could. There was always a connection, despite the distance – two lived in Austria, the others in Hungary. My aunts, uncles, and my father all had cars, so they could visit each other often.

My parents were very young when they met. My father and his siblings attended school in Budapest for several years. The story of Mattersburg and of Burgenland is an Austro-Hungarian history. For some time Burgenland was part of Hungary, and then it was part of Austria.

My father grew up bilingual and finished his last two or three years of school in Budapest for some reason. It was probably during this time that he met my mother. My parents were married in 1920 in the synagogue in Budapest. That was the same synagogue where my grandfather went to pray. The street was called Arena utca back then.

After my parents got married my mother moved in with my father in Ober Waltersdorf. Today Ober Waltersdorf is a town, but back then it was a village. But it did have its own railway station. The next synagogue was in Baden.

We had the only Jewish shop in town. That may be the reason why my parents moved there. Or maybe it was because the village was located near Teesdorf, where my grandparents were living. The salesroom of the shop was about 100 square maters.

There were groceries, fresh produce, and canned goods, wine, beer, soap, and textile dry goods like shirts, underwear, socks, aprons, fabrics and yarns. My father also sold sewing machines; he even had a sewing machine agency. Our relationship with the rest of the people in Ober Waltersdorf was very good until March 1938. I don’t know if we were the only Jewish family in towns. There may have been two or three other Jewish families, but definitely not more.

- My Childhood

I was born 19 April 1932 in Baden, since there was no hospital in Ober Waltersdorf. On the day of my birth my father planted a walnut tree in our garden. A year ago my son and I went to see the garden, and the walnut tree was still standing in all its glory.

Before my parents had the shop in Ober Waltersdorf they would holiday on Lake Balaton. I think they were in Italy once. Later they would often take day trips to Semmering or the Ray mountains, since the shop was only closed on Sundays. My parents would also go very often to Baden for fun.

There they would go to the theater where they played operettas, and to the Kaffeehaus Withalm on Josephs-Platz to dance and where they’d meet up with my father’s sister and hold family meetings. The Kaffeehaus Withalm is still there today. My parents must have gone to the cinema in Vienna.

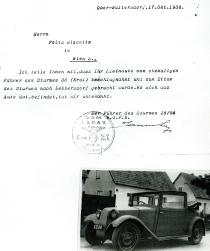

My dad had a lot of friends through his athletic activities. They usually met up in a pub, rather than at our house. He played on a soccer team and rode in motorcycle races for Ober Waltersdorf. The motorcycle had a sidecar. We lived across from the soccer field. My father also owned a motorcycle for the shop, but a special one, since he had to buy and deliver goods. We also had a car. I even have the slip from when the Nazi’s confiscated the car.

In 1938, when we had already been driven out of Ober Waltersdorf, our car was “Aryanized,” meaning stolen. It was a very bureaucratic process and we received this letter with a picture of our car that read:

Ober-Waltersdorf, 17. Oct. 1938. Mr. Fritz Bischitz in Vienna 2nd District

I wish to inform you that your compact car was confiscated by the former leader of Sturm 35 (Kral) and brought to Sturm headquarters in Leobersdorf. I am unaware of the vehicle’s present whereabouts.

Leader of Sturm 18/84

They even confiscated the bicycle.

My father was a great amateur photographer. He had a German camera called a Voigtländer. He could have never afforded a Leica. For a while he thought he would be able to make a career out of his passion for photography and he even studied photography on the side for one or two years. Since there was no color photography yet, he learned to color the photos himself. He used tiny brushes to paint the photos with photo paint, which came in small vials: that was an art.

He was a funny and temperamental man and had a distinct sense of humor. I laughed a lot during the first years of my life, since my father was such a funny man. But he also fought a lot, with every one. When he was riled up he would roar – it was no longer shouting. He fought with my mother, with my aunt, with me, with every one.

Once he was done yelling he would calm down. He’d be angry at the whole world for five minutes, and then everything would be okay again. He could get upset over anything that didn’t suit him. He would even get into scuffles sometimes. Even as an older man. He wanted to beat up one of his customers in Argentina who didn’t want to pay.

My mother spoke German with an Austrian accent. She was also very funny. She had a wonderful voice and loved singing Hungarian folk songs and songs from operettas. She liked working in the shop – the household wasn’t really her thing. So Aunt Ilona took care of the household. Aunt Ilona was there from the beginning. When my parents were married, she came along. She was a wonderful cook. The shop was closed in the afternoons and we would all eat together.

We had acquaintances in town that immediately showed up to our house on the day of the Anschluss. Not all of them, but some, took things from us. In 1938 Uncle Oscar came, Aunt Magda’s husband from Budapest – he was Christian – and brought us all to Hungary.

He was able to bring me, for example, using his son’s papers, and the others with forged papers. It happened slowly, over the course of several months. He brought my mother, my father, my Aunt Ilona, and me. He saved us all.

In Budapest we rented a room in the large apartment of a Hungarian-Jewish family in the 13th district – a working class district. We were allowed to share the kitchen and bathroom.

Then I started first grade; I was six years old. It was a normal public school. There were a couple of Jews there, but not that many. At first I had a hard time managing the Hungarian language, but I learned it quickly. My father and his sisters had gone to the school in Budapest for a while and were notorious.

They had an outrageous wit and were known for their high jinx. When I arrived at the school for the first time, I was introduced to the director as a refugee. The director was a dignified old gentleman with striped pants and a white beard, and he asked me, “So, what’s your name?” “Bischitz.” “Bischitz,” he repeated, mulling this over for a while. “Are you somehow related to a Fritz Bischitz?” “Yes, that is my father.” “By God! Now he’s even sending me his son!” So, he could remember the Bischitz kids very well.

My parents found work: my mother as a seamstress and my father, at first, as a truck driver at a leather factory. They earned enough so that we could eat.

My parents worked until 1942 and I was allowed to attend school. I was even a pretty good student. Starting in 1942 there were the Jewish laws. My parents were never interested in politics. I was the only person in the family who liked talking politics, even as a child. When I was nine or ten, I would often secretly listen to Radio London in Hungarian in the evening. I knew that the invasion in Normandy had begun.

There were quite a lot of Jews living in our building. The family we lived with had a daughter who was about two or three years older than me. I played with her a lot. When the Germans invaded in 1944 the house was declared a so-called “Jewish House.”

A large Star of David was painted on the house and many Jews were packed together inside. We could keep living there and didn’t have to relocate to another “Jewish House.” We had two hours in the morning and two in the evening to go shopping. This became dangerous when we had to start wearing the Star of David.

I read and was involved with politics, and an older gentleman from the building taught me to play chess. We played chess together and talked politics. He owned a leatherwear shop that was also located in our building. He survived the Holocaust and lived to a very old age.

- During the War

At first my father was a soldier in the Hungarian Army, since he had fake papers. Then they found out that he was Jewish and he was sent for labor duty. I think that was 1942. He was sent to Russia. In Russia my father rescued a Torah scroll from a museum. The museum was looted and set on fire. Instead of taking jewels, my father saved the Torah scroll.

He managed to keep it throughout the entire war and afterwards donated it to the synagogue where he and my mother were married. That synagogue no longer exists; the communists converted it into a warehouse. I know the building; I went there and took a look at it. I don’t know what happened to the Torah scroll my father rescued. As the Russians were marching forward, my father was able to return to Hungary.

Before the Budapest ghetto came about following the German invasion in 1944, Jewish women – there were hardly any men left – were deported; even my mother. My Aunt Ilona was slightly crippled and had mobility problems; she wasn’t deported and went with us to the ghetto. She always tried to protect me.

I had become tall, which was a problem, because they almost deported me. They didn’t want to believe that I was just twelve years old. At twelve I looked like I was fifteen. That’s why I always walked stooped over. When we marched into the ghetto they were still taking people from the rows in order to deport them. In the ghetto ten people lived together in one room.

When the Allies began bombing Budapest in 1944 I rejoiced over every bomb. We knew that when we heard the bombs whistling, the danger of being hit was over. I wasn’t afraid. I was still a child, but I grew up during this time. That was a strange feeling.

We had the address of my Aunt Magda and Uncle Oszkar. That’s how I found my father after he returned from Russia, because Uncle and Aunt always knew where we were. We had discussed that we could go to Aunt and Uncle in emergencies and in life-threatening situations. My Uncle got me out of the ghetto when he found out that the ghetto was to be set on fire. He came to the ghetto and brought me a leather jacket with an Arrow Cross armband. I don’t know where he got it from. We marched out of the ghetto together giving the “Heil Hitler” salute.

My uncle then set me up in a monastery with forged papers. After two weeks, on Christmas Eve 1944, the Arrow Cross came into the bedroom at the monastery – there were 20 of us boys there. I knew that I was a Jew, but I didn’t know anything about the other boys, and they didn’t know anything about me.

Jews were hidden in many monasteries. The Arrow Cross came in the middle of the night and said: “Covers off!” And then they went from bed to bed and immediately discovered the circumcised Jews. I was coincidentally in the last row. I am a very calm person, but in this moment I shouted, “As far as I’m concerned you can take all of these Jew pigs with you now, but I want to sleep,” and pulled the covers over my head, turned over, and they moved on.

No one was actually allowed to leave the monastery, but I thought, I need to get out, they’ll be back. There was an old stove in the monastery. I strapped it on, left, put the stove down and went to my Aunt and Uncle’s. Three days later all the Jews were taken from the monastery.

They were led to the Danube, pushed into the water, and shot. I found out about that one month after liberation. An announcement was printed in the newspaper: The parents of a boy who was hidden in the monastery seek contact with someone who can tell them something. They then told me I was the only Jewish child to survive.

My uncle stole stationary from the Japanese Embassy – his workplace – and so was able to forge papers. He brought to a Sweden House, were I saw my father again. For the last two months of the war, my father and I were in one of Wallenberg’s protected Sweden Houses. We starved there and didn’t have else anything to wear. I saw Wallenberg a few times. I remember he always wore a suit and boots. We didn’t know anything about my mother at the time.

There was a kind of resistance movement in our house. They went out into the streets to try to get food and look for Russians. One time two Germans came to the house. They entered, but did not leave. The members of the resistance movement killed them. There was a lot of bombing and shooting.

Then, suddenly, the doors were thrown open and the Russians were there. We joyously welcomed them, of course. They weren’t especially friendly to us, but to us, they were God. I then tore off the yellow star, unfortunately; I could have held on to it.

Afterward my father, Aunt Ilona, and I lived with Aunt Magda and Uncle Oszkar. Uncle Oszkar had saved the lives of around thirty relatives, even distant ones. We submitted a bid to have a tree planted for him on the Avenue of the Righteous at Yad Vashem. Aunt Magda died in Budapest in 1984.

The Red Cross hung lists of survivors throughout the city. I went every day and one day discovered my mother’s name. On the list was written: Irene Bischitz, survivor of the Dachau concentration camp. My mother was in an American hospital in Germany. She only weighed 35 kilos. From the hospital she wrote to Ober Waltersdorf, since we had arranged with her that we’d either meet at our aunt’s in Budapest or in Ober Waltersdorf.

In the meantime my father and I had gone to Vienna with Russian soldiers – at this time there were no borders and you didn’t need any documents – in order to look for my mother. We walked from Vienna to Ober Waltersdorf, to the town hall, and they said, “Yes, Mrs. Bischitz has written. We know where she is and we will officially confirm that Mr. Bischitz and his son have survived.” That’s how my mother learned we were alive. Then we met up in Budapest and left for Vienna together.

My parents didn’t think for a second about going back to Ober Waltersdorf. My father got a bombed-out apartment for us in Vienna, because he promised to fix it up. He opened a textiles shop in the same building. I went to High School on Zirkus-Gasse, in the 2nd district.

I needed to readjust to the German language, but at that age it wasn’t a problem, it only takes one or two months. One problem was the schoolbooks, which were still from the Nazi era. The texts were written in a gothic script that I couldn’t read; that’s something I had to learn.

I assume most of the teachers were Nazis. Of course they never admitted it. Despite that I never had a problem. I immediately told each one I was Jewish. I was pretty tall and fairly strong – and very proud of that. I was a member of Hakoah, was a swimmer and water polo player.

I was even the newspaper sometimes. I was one hundred percent integrated at school, but my only friends were from Hakoah. I never had a Christian friend – perhaps this was because it never came about, or maybe because, subconsciously, I didn’t want any.

- After the War

We lived in Vienna’s 2nd district until 1951. The district was part of the Russian sector, since the allies had split Vienna into four sectors after the war. Then the Korean War broke out. My parents thought that the next World War was coming and that I’d have to go to the military.

They wanted to leave – namely to a country that didn’t have military service, so not to America or Canada, not to Australia. That’s how they came up with Argentina. In Argentina there was only military service for those born in Argentina. Part of the Glaser family had survived there and they sent us an affidavit.

I didn’t want to leave Vienna. I was 19 years old and had my friends and sports in Vienna. But it would not have occurred to me to rebel or stay there on my own. Well, the prospect of becoming a Russian soldier didn’t appeal to me either.

I would have preferred to go to America; I always liked the American. I learned English in school and saw American films in the cinema. But my parents didn’t want to go to America. A took Spanish lessons a few months before we fled again.

First we took the train to Genoa, and from Genoa we went by ship to Argentina. It was a lovely journey – and an adventure for me. I had never written a journal, but I have one from this trip. Our relatives picked us up from the port in Buenos Aires. They had rented a room for us in a boardinghouse for the time being.

We didn’t come to Argentina as rich people, but we weren’t poor either. At first there were three of us. Aunt Ilona arrived a few months later because her papers weren’t finished in time. My parents were really afraid of the Korean War. This wasn’t an escape from one day to the next – but once our papers were completed they immediately bought tickets for the ship.

The next day I went to find out if there was a Jewish sports club and immediately joined one. I continued to play water polo, swam, and made friends with the members of the sports club. They were Argentines, some were the sons of emigrants and others had immigrated before the Holocaust.

I began working, since school was out of the question. I would have had to have everything recognized. I had finished my exams at the trade school in Vienna, but in Argentina I would have probably had to study for months and take exams. I didn’t want to do that. My father began working at a textile print shop, and I joined him.

My father had two co-partners, and after a year no co-partners and almost no money. That happens fast in Argentina. Then my parents opened a knitting factory, which developed nicely. We all worked in the knitting factory – even my wife after we were married.

New immigrants arrived to the building we were living in: Czechs, Austrians, and a Hungarian family with their daughter. The daughter went to school with my future wife. That’s how we met. We were engaged for one year, then we had a Jewish wedding in the large synagogue in Buenos Aires.

My wife’s maiden name is Ida Lubowicz. She was born on 27 July 1937 in Lutsk [today Ukraine], which was in Poland back then. Up until the end of the war she lived with her parents in hiding in Poland. Then they immigrated to Italy and then to Argentina in 1951. My wife’s mother tongue is Yiddish.

My wife can’t speak a word of Polish; they only spoke Yiddish at home. She went to school in Italy the first years. She finished her exams in Argentina and then worked with my parents and me in the knitting factory.

My parents-in-law and their children were the only survivors of what was once a very large family. Once, after the war, my wife went to Poland with her mother. They wanted to look for relatives. They didn’t find anyone; they had all been murdered and she – a 16-year-old girl at the time – was called a “Jewess pig” on the street.

We had two children. Our son, Roberto Bischitz, was born on 5 November 1959 in Buenos Aires and our daughter, Deborah Weicman, née Bischitz, was born on 19 April 1965. Our children were raised Jewish. Both completed their exams at the Pestalozzi School in Buenos Aires.

That was a bilingual private school for German and Spanish – I’m sure 50 to 60 percent of the students there were Jewish. Our children joined youth groups that met once a week in the synagogue. We went to the synagogue together on holidays. Naturally my son became a Bar Mitzvah when he turned thirteen.

My father-in-law and I got along very well. I met him fifteen years before his death when he was a powerful and very sensible businessman. I loved my in-laws and they loved me – we had a lovely family life. Every Friday my mother-in-law lit candles and went to the synagogue.

Within two years my parents and in-laws all passed away. My father died in 1971, my mother in 1973. My father-in-law had a stroke and was paralyzed for seven years before he died. My mother-in-law died of cancer.

The economic situation in Argentina became progressively worse. In 1984 we relocated to Vienna. I was never too fond of Argentina; I could never get used to the South American mentality: the unpunctuality, the people’s payment morality, the climate. I always thought differently than the Argentines.

Probably I always remained a European. My wife was an enthusiastic Argentine back then. She had her two brothers and their families in Buenos Aries. Today you simply can’t live in Argentina any more, it’s terrible: unemployment, poverty, and there’s a murder every three hours.

So we went to Vienna and lived first in the 7th district. I worked as a sales representative; I had textile agencies from Portugal.

My son was 25 and had married an Argentine Christian in Argentina. Even my daughter-in-law came to Vienna. She worked and my son went to the Technical University for a few years. He wanted to be an engineer, but then discontinued his studies. He is self-employed and teaches rhetoric.

We have a granddaughter, Nastassia. She is my son’s daughter. She lives with her mother in Buenos Aires. Their marriage fell apart and my daughter-in-law went with the child back to Argentina. My son stayed in Vienna and flies back to Argentina as often as he can. Now that Nastassia is older she comes to Vienna once a year and stays for one or two months.

My daughter didn’t like Austria. She worked for some time as a saleswoman at Schöps [a textile chain] on Stephans-Platz. But she is a real second-generation Holocaust victim. She wants nothing to do with Germans and Austrians. She told us, “I am Argentine and lost nothing in Austria.” Then she returned. She worked in Buenos Aires as a trilingual secretary. Unfortunately she is unemployed at the moment.

She is an especially good Jew, but she isn’t religious. As it was with me, it would have been impossible for her to marry a non-Jew. She was, of course, married in the synagogue; that was self-evident for her. My son is different in this regard.

We went to Israel a few times. I am not a Zionist, I was never a Zionist, but I liked it there. I am unconditionally pro-Israel, but my wife and I never thought about living in Israel. We liked it, but we were tourists and knew that we were tourists.

I was often in Hungary for business. For years I was in Budapest once a week. When I see old Hungarians I imagine them in Arrow Cross uniforms. I am not fond of Hungary. Budapest is a beautiful city, but God forbid having to live there!

Until Haider, I had successfully repressed the past – consciously or unconsciously. I don’t watch any films or read any books about concentrations camps. My wife is always watching those kinds of films. Though after Haider the past was somehow opened.

I have no memories of the Austrian Anschluss or the persecution in Austria. I only hate the Hungarians. To me the Hungarians are the Nazis. I like being an Austrian, and you could almost say that I love Vienna. I like being here and don’t have the same problem most people have – even my wife – when they see old people. If they’re wearing beautiful jewels, for example, they always ask themselves: Which dead Jew do those come from? That would happen to me in Hungary.

In Hungary I was always getting into fights at school, because they would call me “Jewish swine.” That wasn’t in Vienna. Only once did I take revenge. On the first day after liberation I beat up the boys that had always tortured me at school. I sought them out, found them, and trounced them.

Later I had a few Jewish customers in my business in Vienna. All the other customers knew that I was Jewish, but I never had a problem. I never made a secret of it. Besides which I probably look Jewish, and the Austrians – I know my countrymen – can somehow smell the Jews.

I know that they’re anti-Semites. I’ve just never felt it myself. I know that they murdered. I know that, relatively speaking, there were more Austrians in the SS than Germans. I know all of that. I also know that Hungarians are worse anti-Semites, and that the Poles and Ukrainians are even worse. I am aware that they are, for sure: unconscious and hidden – and nowadays not so hidden.

I felt really good, felt very at home, after returning to Vienna. I didn’t get too upset over Waldheim. I mean, if this man was UN Secretary General twice in a row, then they had really put him through his paces. I am also still convinced that he wasn’t actually a Nazi, just a liar and an opportunist. He just worked through the past in his own way, namely by repressing it.

I have my problems with Haider. I’m convinced that he’ll never become Federal Chancellor, only I was also convinced that his party, the FPÖ, would never get more than ten percent of the vote, and then they got 25 percent! But I do believe that it’s over now with Haider.

There has and always will be anti-Semitism. I don’t know who said this: Anti-Semitism isn’t a problem with the Jews; it’s a problem with the anti-Semites. Only we have to live with it.

We live in a building from the Jewish Community. Our Jewish life has been more active since we’ve been living here. We receive the Jewish Community newspaper and go to events. Once a month we also go to a meeting with the former Hakoah people in Café Schottenring.

I always say, whoever in Vienna wants a Jewish life with these few Jews, can attend some sort of event every day – not a problem. We don’t live a religiously Jewish life, but rather a social Jewish life. But of course we go to synagogue on the High Holidays.

My wife never really settled into Vienna. Our grandchild is in Argentina and she is very close with her younger brother in Argentina. Of course it hurts her to see the family in Argentina so infrequently. But ever since we founded our own “ghetto,” so to speak, in our building, things are going better for her. But that might also have something to do with the fact that she can no longer feel at home in Argentina. And we’re too old to leave Vienna.