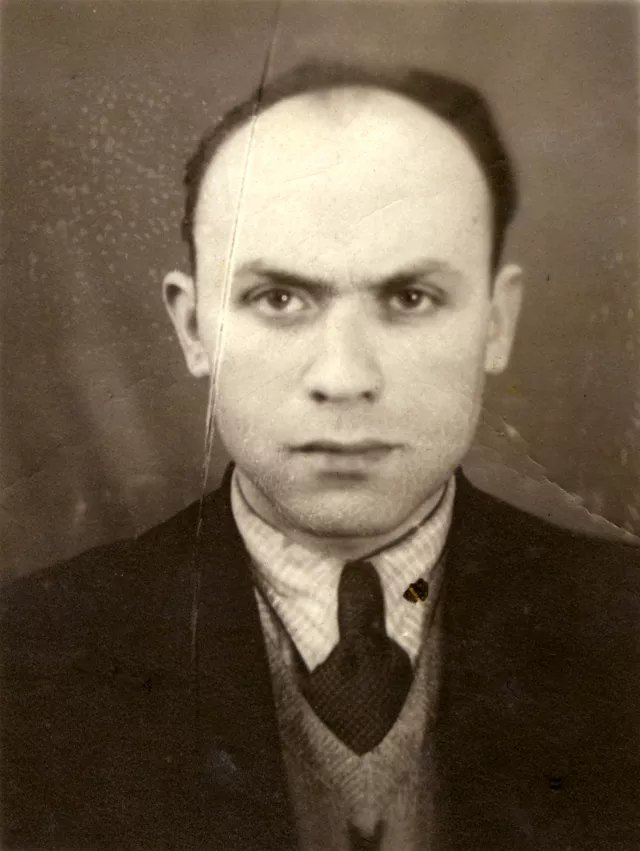

‘As a sign of my appreciation. Furman. Komi-Aykino...’ It’s a friend from USSR, who was with us in Komi. I don’t remember anything about him... But I can say something about this place. Komi.

I was in Brzesc with my father. In 1940 they came in the night, told us to pack our things and leave with them. I had stashed a medical insurance ID. Birth year 1921, I added a dash, first I tried the ink so that the color matched, now it was a '4' and I was three years younger. Because I was afraid they'd separate me from my father. And so: families they sent to the north, to Komi [republic west of the Ural mountains], to Siberia, various places. And singles - to a camp.

We traveled for a month. At first by train, in the night. We'd stop somewhere and they'd bring us something to eat. A soup made of nettle or some other weed, we could draw some water. At first they locked the cars and set up a semi-toilet in the middle. What - everyone will sit and look at the others looking at him? So we kept losing the locking rings. Until they gave it up and left the door unlocked. But no one ran away. Where were we supposed to run without any papers? They'd have caught us right away. Then we sailed for so many days on a ship, a kind of hollowed out barge, there was one toilet on the top and that was it. Then they let us off in the taiga and we had to walk for some… Twenty five kilometers? Into the taiga. There we lived in barracks, some twenty families per barrack. Those who had sheets, had sheets; those who did not, did not. And work, usually in the forest. All women didn't have their period for a year after coming to Komi. The different climate. I was a maiden, I knew I wasn't pregnant, but the married ones were worried. And there, in Komi, we stayed in the forest for something like two years. Perhaps it's the flow of time that it seems to me like ten years, but no. And then they let us go to the countryside. And in the countryside we started working as watchmakers. I also worked as a watchmaker. I could install a spring, clean a watch. But I didn't do much because my father never wanted to agree for me to be a watchmaker. I was for a total of four years in Komi with my father. We were in exile, but free.

The local 'folklore' is the more pleasant part of the story. We rented a room and lived with a family. Unfortunately, we had to sleep together because we had one blanket, one pillow, and one bed. The blanket and pillow were ours. Later they gave us a little single-room house, we made a partition with boards, and here you worked and there you slept. At the side stood an iron stove that during the winter you heated around the clock. With wood of course. We kept chopping and sawing wood.

It was like that: you work, but in the summer they send everyone to the forest for the forest produce. I fell in love with the forest only in the taiga. Most of the trees there are of the northern variety, spruces. They were sky-high. Covered to half-height with gray moss, they looked like standing whitebeards. Beautiful! There were water holes, swamps. There was permafrost. During the heat of the summer there was still snow in the deep ravines. Doesn't it look strange? Berries larger than cherries. It was there that I saw the bog bilberries for the first time.

When it's, say, harvest time, everyone goes to help. The first time I took a sickle, I cut myself here and I still have a mark. I cut it to the bone. Because I couldn't operate the sickle, I handled it the wrong way. They said I didn't deserve to eat bread if I couldn't harvest it. No peasant there owns his own cow. He doesn't because during the two summer months he won't be able to mow enough grass for food and litter. So, if the family has many members, he owns half a cow. If the family has few members, he owns quarter of a cow. What does it mean? It doesn't mean the cow is today here and tomorrow there, because everyone would count on the other to feed it and the cow would starve to death. The cow spends one week with one farmer, one with the other one, one with the third one, and so on. And when it goes to graze, it knows perfectly well: this barn is closed, so it goes to the other one, the second one is closed, she goes to the third one.

We worked hard and our life was difficult. But if you walked or rode through the forest, the world was beautiful! The trees all in snow, the roads white. And I sang, sang out loud, because I used to have a very nice voice. Soprano. The world was beautiful, so what that it was hungry, cold, and far from home? White nights, superb. And the northern lights. It's so wonderful. The colorful, beautiful curtain hanging in the sky. You saw many things. And what you saw, no one will take away from you. Everything there was interesting.