Alena Munkova

Prague

Czech Republic

Interviewer: Zuzana Strouhova

Date of interview: October 2005-March 2006

Mrs. Alena Munkova, née Synkova, was born in 1926 in Prague into the family of dentist Emil Synek, who was politically and professionally active, and his brother Karel was head of a well-known publishing house and bookstore in Prague, which he took over from his father, Adolf Synek. When Alena Munkova-Synkova was ending Grade One, her mother died of cancer. Her father remarried, but his second wife also died of cancer five years later. Right before the ban on mixed marriages 1, her father married for a third time. Because Emil Synek was protected by this marriage, the first to be summoned for transport to a concentration camp was Mrs. Munkova's older brother, Jiri, who didn't report for transport, and survived the war in hiding. Mrs. Munkova was summoned some time later. She left for Terezin 2, where she was protected from further transport to Auschwitz by the fact that she was considered to be a half-breed. After the war she returned to Prague, where she lived for some time with her stepmother, who had also survived the war, even though she was arrested by the Gestapo along with Mrs. Munkova's father, apparently on the basis of some denunciation, and both ended up in a concentration camp. Her father, however, died in Auschwitz. She graduated from the Faculty of Journalism at the University of Political and Social Sciences, and started working on animated films at Barrandov [a well-known film studio in Prague], from where she was however thrown out due to her Jewish origins. But after several detours she finally returned to film, and until retirement worked as a dramaturge in animated and puppet films. Today she lives in Prague with her husband, Jiri Munk, an architect, and is still very active.

Family background

My paternal grandfather was named Adolf Synek. He was born on 1st November 1871. According to records at the Jewish community in Prague, it was in Mitrovice, in German written Mitrovitz. But I don't know, translated into Czech it could be Mlada Vozice, by Tabor. All the Syneks were from southern Bohemia, from around Tabor. I came across this publication that came out not long ago, about old companies from this region, where there were lots of Syneks. It was probably this regional name there. Grandpa's brother Bohumil, however, wrote it with an 'i,' which was most likely a question of birth certificates. When I retired I also had a problem with it, because some of my documents have an ''' and others a 'y.' As far as I know, my father's grandparents were from Mlada Vozice, but I don't know anything more about them. They probably weren't big landowners, I'd say that more likely they were agricultural workers or merchants. I don't know, I'd be guessing. Grandpa died on 20th January 1943 in Terezin, where he went on 20th November 1942.

My grandfather definitely didn't have a university education, he was a tradesman, and apparently had studied somewhere in Vienna. But his mother tongue was Czech. He then worked his entire life as a book-seller and publisher, the two were usually connected back then. He became famous by having the monopoly on Hasek's Schweik 3. Then he had this edition named 'Minor Works of Major Authors' or something like that, which were classics, beginning with Thomas Mann and ending with I don't know who. [Mann, Thomas (1875 - 1955): German writer, philanthropist and essayist, awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929.] I don't know how Grandpa came by that publishing house, but it was in the city ward of Prague 7, on Letna, on Janovskeho Street, which I think is still named that. I remember going to visit him as a small child. The bookstore was down on the ground floor, so I would always stand on the windowsill, and he'd always take me down off the window.

Uncle Karel then took over the publishing house, sometime in 1936, and moved it all to Vodickova Street. It's the store opposite the street named V Jame. Besides the publishing house and bookstore, there was also this so- called 'Karel Synek's Children's Corner,' where there were some toys, too.

My grandfather had two brothers, Bohumil and Rudolf. Bohumil Sinek was born on 19th October 1872, and on 10th July 1942 went to Terezin. He died in Treblinka, but when, I don't know. Rudolf Synek was born on 5th January 1876, and on 25th April 1942 went into the transport, and they took him to Warsaw. I never heard of anything going to Warsaw before. To Lodz 4, there yes, those went in 1941. But this is what it says in the records at the Jewish community [in Prague]. With a cross, that he died there. No one knows when, but probably in 1943. If he left for there already in April 1942, then he couldn't have survived longer than that.

All I know about his brothers is that they were probably members of the wealthier class, because Bohumil owned at least one building, which I was then supposed to inherit. This was because Bohumil didn't have children of his own. But there was probably more than one building. I remember that he lived on the corner of what was back then named Sanitrova Street. But the building he owned was somewhere else, on Bilkova Street.

I also remember that I was in that building when the funeral of T.G. Masaryk 5 was taking place. You see, the funeral procession was going to pass by there, so about fifty of us gathered there, from my point of view a huge number of people, there was all sorts of food served, and we watched. It was apparently all relatives, who I hadn't even known existed. I was about eight or nine years old at the time. Back then I had this feeling that those people didn't even have jobs. On the other hand, they were already older men, so I don't know. Perhaps they were some local businessmen, I don't know, I'd be making it up.

I don't know what Rudolf did. All I remember is that he had a large mustache. He had two daughters, Marta and Irma. Her [Irma's] husband was named Iltis, and after the war he was in charge of a magazine at the Jewish community. They had a daughter, Ruth. But then they divorced and Irma and Ruth moved away to Chile. And then I found out by chance, and it's not that long ago, that they both died in Israel. That they had moved, I don't know when and why, from Chile to Israel. After many long years, apparently. Marta was still here in Prague after the war, but I don't know anything at all about her. Suddenly she wasn't there anymore, most likely she died.

My grandmother was named Terezie, her maiden name was Löfflerova, and she was from somewhere in Slovakia. I don't know anything about her parents. But they probably weren't overly wealthy, because she went to Vienna to work as a servant. But that's just my hypothesis. Her education was most likely a basic one. She met Grandpa in Vienna, where she was working as a servant. That's where they probably got married, because my father, Emil Synek, was born there, but relatively soon they moved to Czechoslovakia.

She died in 1939 in a mental institution. Her sister and their mother were also mentally ill, so I've got this good family medical history. I don't know exactly what she had, back then they probably didn't classify things. Maybe it was some sort of dementia or something like that. I myself, as a ten-year-old, saw visible signs of lack of concentration and distance from reality in her. And I know that she had a horrible clutter in this large embroidered bag that ladies carried back then. So there were already some seeds of schizophrenia or some nervous disease there. Otherwise she was exceptionally kind and affectionate, and saw herself in her grandchildren, as it usually is with grannies.

She's buried at the new Jewish cemetery in Prague, I've found this out only recently. At that time they weren't burying people at the old cemetery much anymore. But she doesn't have a tombstone, because in 1939 that was already forbidden. I'm going to have to have one made. Whether she herself lived in some Jewish fashion, that I don't know, we didn't talk about things like that at home at all.

The Synek family was completely assimilated. It's true that I didn't see my grandfather's brothers, Rudolf and Bohumil, so there I don't know. As far as Grandpa Adolf goes, I don't at all remember there being anything, him celebrating some holidays, although both we and Grandpa lived on Letna, close to each other, so I would most likely have noticed something. But I don't remember anything like that. All I know is that my father, who was very liberal, had me 'liberated' from religion classes, because he wanted, as he later told me, for me to one day choose for myself. But by me that was a mistake, because it belongs to one's education. And I remember that they kept it a secret from my grandfather. That apparently he'd have been upset, so obviously there were at least some traditions there. What's more, his two sons, both my father and my uncle Karel, married Christian women. With my uncle it was his first wife, with my father not until the second and third.

My grandfather on my mother's side was named Bohumil Steiner. He was born in 1871 in Kovansko, Nymburk region. But back then it fell under Kolin. He lived in Kolin, where he was in the textile business, I remember the store. He died on 20th October 1932, a year before the death of my mother, his daughter Marie. Probably in Kolin, because somewhere I had some documents about what Grandma had paid the funeral service, and that was all in Kolin. So he's most likely got to be somewhere in the old Jewish cemetery in Kolin.

My grandmother on my mother's side was named Hermina, née Fialova. She was born on 10th August 1869, so she was two years older than Grandpa, which was very unusual back then. On the contrary, men used to be for example twenty years older. I've also got a younger husband, so I'm continuing the 'tradition.' After Grandpa died, my grandmother moved with my mother's sister, Anna, from Kolin to Prague.

Exactly when I'm not sure, but it probably took a while for them to wind down the store. Because Grandpa had a textile store in Kolin, in this little street close to the town square. I remember that the entrance was right on the street, and in the courtyard there - it's as if I saw it in front of me even now - there were cobblestones, that had grass growing up between them. Back then, as a child, I was very interested as to why there was grass growing up between the cobblestones there. A colorful impression like that stays with you your whole life.

My grandmother and Aunt Anna also had some little store in Prague, in Smichov, but they went bankrupt right away. They then had it in Zizkov [a quarter of Prague], and again went bankrupt. I guess they weren't good at it, my grandmother had probably never done it. She died sometime during the war, most likely in 1942. I don't know if she had any siblings. I later lost contact with them, because after my first mother died, my father remarried, and although that second mother of mine was very kind, she was afraid of me having contact with that original family. But I used to go to Zizkov around once a year anyways. I remember that they lived at 5 Milicova Street. But as soon as I walked in, my grandmother would start weeping, because as soon as she'd see me, she'd right away feel sad that her daughter had died. I remember her as being very slight, this proper grandma, delicate. But that's probably a bit of a fabrication after all those years.

I remember my grandfather being very tall, and my grandma small. My mother and aunt were also relatively small, I probably inherited it from them. But Grandpa Steiner, he was tall. So at least my brother, Jiri, isn't such a shrimp. I used to envy him that a lot. But on the other hand, I've got my grandfather's eyes, their shape, setting, look, color. Our father had grey eyes, Mother was dark-eyed, but I've got quite intensely blue eyes after Grandpa. Genes are genes.

As far as my mother's parent's religiousness goes, there I don't remember anything. We used to go see Grandpa, I remember him playing with me and I used to get fabric scraps from him. And I know that Grandpa used to take my brother Jiri, who was five years older than I, with him to the fair, where he always used to display his wares. But I don't remember them celebrating any holidays, for example.

My father, Emil Synek, was born in Vienna, as I've mentioned, on 1st June 1894. He apprenticed as a dental technician, and then took some exams, so he was a dentist. He studied to be a dental technician and lab technician, and then wrote some exams, so he was a dentist. Which means that he could pull teeth and in general do everything on the level of a dental surgeon. He had his own large dental practice on Letna. He was also very active on the dental panel, and lectured and I don't know what all else. He was very active in his profession, and was always educating himself and studying dozens of professional magazines. I think that he was one of the first ones here to have an X-ray machine. I remember that it was from Siemens, that company supplied it to us from Germany. But he wasn't a physician, he was a dentist.

By the way, he was very popular, because he used to fix teeth for the Sparta soccer team 6 for free. It was in general characteristic of him that he fixed a lot of people's teeth for free, when they didn't have money. He used to say that he'd make it up on the rich ones. These days he wouldn't be able to exist, he'd go out of business within a year. He had a strong sense of social responsibility, which was common in rich Jewish families.

My father was in the army during World War I, but he never told us where and for how long. But I do know for sure that he told us that he was in uniform in 1918, when Austrian emblems were being torn down. That revolution in 1918 was a big experience for him. But he probably didn't spend much time in the army, because he was wounded in some way. Even though who knows how it was, because my father was quite dead set against war, he'd always been an anti-militarist.

My father had one brother, Karel. He was somewhat younger, I think he was born sometime around 1896. He married Vlasta, née Kolarova. She apprenticed as a dental technician at my father's where she met my uncle. Vlasta wasn't Jewish, so my uncle would have survived the war thanks to that mixed marriage, but they divorced because of property. Probably in 1940 or 1941. My aunt was probably afraid to live with a Jew. I wouldn't say that it was only for the sake of appearances, because after that they didn't live together anymore. I think that my uncle then lived with his father, but I don't know exactly. He used to come to our place for lunch. Already before his departure for Terezin, my uncle had open tuberculosis - I remember that we always used to wash all the dishes with permanganate - and he died of this disease in Terezin, in 1943.

Karel and Vlasta had two daughters, René and Milena. René is a year younger than I, she was born on 23rd September 1927. I remember that when we were in public school, we'd always walk to school together, because they also lived on Letna. René then married Igor Korolkov, who was from a Russian émigré family, and after the war they moved to Holland together. She's still alive, in Amsterdam, and her husband died two years ago. Before moving away, René was a seamstress by trade, and then studied at the Faculty of Philosophy, but didn't finish. In Amsterdam she then had a large fashion studio with many employees, where they used to make higher-quality clothing.

The second daughter, Milena, married name Kuthejlova, was born in January 1937, I think. She graduated from economics at university and worked in television, where she worked as an editor for magazines about TV programs. I think that she's perhaps still there now, as a retiree - she's eleven years younger than I - and works in the library. I don't know exactly.

My cousins didn't go onto the transport during the war, because they were half-breeds. Few people know that according to the Nuremberg Laws 7, the year 1935 was a defining line for children from mixed families. Children that were born before 1935 and weren't registered at the Jewish community, which both my cousins weren't - this also shows how religiously inclined our family was - were therefore so-called Aryan half-breeds. Children born before 1935 who were registered at the Jewish community were so-called Jewish half-breeds. And children that were born after 1935 were Jewish half- breeds, whether they were registered or not. I know this because I myself was considered to also be a half-breed, which saved my life. As far as religion goes, as I've indicated, Uncle Karel didn't live in any particularly Jewish fashion, he didn't observe anything at all. I don't know how deeply he felt his Jewish origin, but the Germans then made sure of reminding him of it.

We of course saw my uncle's family, the family stuck together. I also used to see my cousin René quite often. My father was at one time in the Zinvnostenska Party 8, because he was for the middle of the road as a matter of principle, and his brother, Karel, apparently used to try to convince him to vote for the National Socialists. But I don't know how it ended up. My father was perhaps even active in that Zivnostenska Party within the scope of Prague 7, but I don't know anything exact. He was also very active on the Board of Dentistry, where he used to lecture and perhaps even had some sort of function, I don't know what kind.

My father was in general very sociable, quite often he'd go out in the evening, to cafés and so on. Within the scope of these groups, as an eleven- year-old, I used to play in some theater and used to attend Sokol 9. There I also had my first conflict, when they yelled 'Jewess' at me. My father was active in the Czech-Jewish Association 10, assimilated Jews that identified with the Czech nation. They published the Rozvoj weekly, which my father subscribed to.

My mother was named Marie, née Steinerova. She was born on 9th August 1898 in Kolin - she was four years younger than my father - and died before the war, in 1933, of cancer. As I then found out, her father had also died of cancer, a year before her.

How did she and my father meet? I don't know, my mother was from Kolin and my father from Prague, but back then couples apparently used to meet through all sorts of matchmakers, and it was said - don't take this completely seriously - that my father needed a rich bride so that he could start his dental practice. Up till then my mother had been at home, as was right and proper for young ladies back then. She definitely didn't have any sort of university education, but she played the piano beautifully. She was quite a melancholic, and used to play for days on end. I don't have any idea what sort of high school education she had either. Maybe someone used to come and give her piano lessons. That would have been appropriate for that social class. Young ladies knew how to cook, sew and play the piano.

I don't even know what her religious inclinations were like, I was six when she died - it was at the end of Grade One - she'd already been ill for the last two years.

My mother had one sister, named Anna Schwelbova. She was born on 10th December 1904. She was married about three times, and with one of her husbands, some Neumann, she had a son, Zdenek, who was two years older than I. I think that Neumann, but that I'm not sure of, maybe it was Schwelba, was a barber or hairdresser, something like that. Anna, her son and her mother, my grandmother Hermina Steinerova, went onto the transport already at the beginning of 1942, and maybe didn't even go through Terezin, but straight away somewhere further on. I think that they died somewhere in Poland.

Growing up

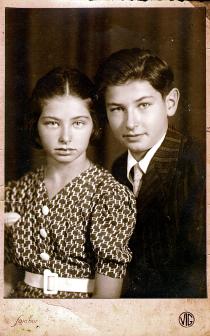

My name is Alena Munkova, and I was born on 24th September 1926. I was born in Prague, and besides Terezin, I've never lived anywhere else. I've got one brother, who was born in 1921. He was born on 26th November. His real name is Jiri Synek, but he's known by his artistic name of Frantisek Listopad [Listopad, Frantisek (b. 1921): real name Jiri Synek, Czech poet and writer of prose]. I'm giving his artistic name, because he's quite popular under his pseudonym abroad as well as here. He's had several books published, and also does theater.

My parents had one more child, born before me, but it soon died. So I don't have any other siblings, not even step-siblings. Because my father married two more times, but didn't have any children with any of those women, and neither did they have any children from previous marriages. They were divorced and childless when they married him.

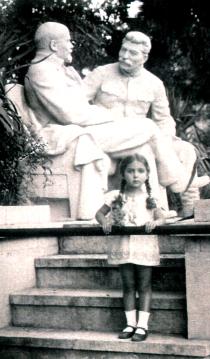

My childhood is much interwoven with Letna, where I lived. I really was rooted in that sidewalk there. The way they say a person has roots in land, here it was the sidewalk, with its paving stones. I knew all the store owners on Letna, I used to run to the park there, and to Stromovka [Park]. And the loss of that place where you grew up - and certainly it's different for everyone - can't be renewed again. A person pretends a bit, but it's gone. After the war I did return to Letna, but everything was different. But to this day, when I walk by Letna, I feel a twinge. To this day, I smell that aroma, what it smelled like there. I remember colors a lot, and smells perhaps even more. I think that childhood forms a person, whether he wants it or not. Or also deforms.

So before the war, Letna was my whole life. I've got this memory of our apartment building's courtyard. It's still there, No. 1, we were on the ground floor, on the corner. Back then it was Belcrediho Avenue, now it's Milady Horakove, if I'm not mistaken. Then they made it into a bank, and now I think there's a KFC there. From bad to worse. Back then, when you entered the building, and I even think that the doors are still almost the same, in horrible condition, there on the end of this L-shaped hallway, was the entrance to our apartment. But on the other side, right after the apartment door, was another door, which led into the waiting room and into the clinic. So the entire ground floor was divided among my father's dental practice and our apartment.

Then there was of course a courtyard, where I used to play. People used to hang carpets there, there were these two small trees, and it was all quite grimy. And on the ground floor of the building there was a man with a junk shop, named Andrle. He was a mysterious figure, and I never had the courage to go down into the basement. By the way, back then those apartments had toilets in the hall, not in the apartments. But the toilet was of course only ours.

I don't remember us having a maidservant in that first era, because my mother was at home, and there was a building caretaker there who used to do things, and someone also used to come over and do the laundry. So maybe there was some sort of help, some sort of cleaners and so on. My memories of that are of course very foggy by now. But a servant as such wouldn't even have had anyplace to live there.

Before I started going to school I was at home, but from what I've been told, my older brother Jiri attended French nursery school that last year before he went to school. But I remember being in Brevnov with my mother, and I even know about where the staircase was that she used to lead me up to dance school. I was five at the time. In one of those dance schools for little children I was even supposedly supposed to play a part in some theater, back then it was the German Theater, which today is the State Opera beside the main train station. But my father forbade it, that he didn't want me to grow up to be in the theater. Despite his being such a liberal, something conservative inside him reared its head. I remember being terribly sad because of that. I guess my mother didn't succeed in forcing the issue, or didn't want to, I don't know.

I don't remember any family vacations or trips, that's already quite foggy, maybe my brother would remember, he is five years older, after all. All I remember are the trips to Grandpa's in Kolin.

Then I started Grade One. From this time I remember that an apprentice from my father's lab used to come get me after school. I would always come with untied shoelaces, so he'd always tie them for me. I've got a very strong memory of this. The apprentice would kneel and tie my shoes. That's quite cute. I don't know if we always had gym class, or why I didn't have them tied. But back then people wore lace-up ankle boots, not sandals. I think that by then my mother was quite ill, and so no one was really taking care of me much. That it's the result of there being no one to tell me: 'You've got to tie them yourself.' That's why I'm talking about it, not because of those shoes. That I was actually a bit of an outsider, not on purpose, but because of the situation that existed in our family.

But that was given by the fact that our mother was dying, and I think that the cancer lingered on quite long. I remember being in some room, in some dining room, and my mother is lying in the next room, and Grandma Hermina, who'd come for a visit is with her, and my mother is weeping horribly. They didn't know that I was listening. And my mother is saying, 'What will become of the children, what will become of the children?' And Grandma is consoling her.

That was a horrible experience for me. For one, I didn't want them to know that I could hear it, and then, for a child, suddenly something opens up in front of you, you don't even know its exact scope, because the words aren't completely filled with content, but despite that you know that it's something terrible. That it's something horrible, unjust, cruel, something that you can't defend yourself against. That was a very terribly strong moment for me at such a tender age. I was six then. Later I even wrote this poem about it. I also remember how horrible it seemed to me when then our teacher announced it to the class, and said, 'Your poor classmate's...' It was awful. Even though she probably thought that that was all right, she didn't know how else to react. You can't judge that at all.

By the way, that teacher was named Helena Tumova, and she was an old maid, because during the First Republic 11 teachers were usually single, unmarried women. I remember her being very strict, but everything that I know how to do, I know from those first years when she taught us. Everything that I know in Czech, I know from her. It was a perfect foundation.

I don't remember what went on after my mother's death, it's a blank spot for me. All I remember is us moving to another apartment. This is because our father remarried, but that second wife also died of cancer five years later. That must have been something insane for my father, an absolute train wreck. I was twelve, so it was most likely in 1937 or 1938. That wife was named Marta, née Polakova, then Erbenova, and Synkova after my father. So she was once divorced. She was also a dentist, so they obviously probably met through work. She was a Protestant, from a Protestant family, but that didn't play a role at all. I never had any conflicts with her, she was great. Then when she became seriously ill, I used to sit with her a lot, because by then I was already eleven or twelve.

I remember that my brother refused to call her Mommy, and called her Marta. He rebelled. Well, he was in the full bloom of puberty at the time. There were frightful conflicts because of it, but our father didn't break him. I myself called her Mom. Not Mommy, but Mom. I didn't have any inhibitions in my relationship with her, but I was a little bit afraid of her. She was large and dark, and was relatively, as people from a Protestant environment are, or were, strict and high-minded. Something like that was present in her.

What's more, she was no longer all that young, and it was hard for her to relate to children. With me it still somewhat worked, but she probably never found a way to have a relationship with my brother. She herself had no children, and was an independent, emancipated woman - back then there weren't many women studying medicine either - so I'm convinced, that is, it's my deduction, but for sure a correct one, that it was a problem for her to marry a man with two children. And what's more with a son in puberty and rebellious. For sure our father was also troubled by that situation.

As I've said, my second mother was also a dentist. Our original apartment became her clinic; we created a large waiting room and laboratory there, where she worked on teeth. We had several employees in the laboratory. We moved to what was at the time Belskeho Avenue, now I think it's called Ulice Dukelskych Hrdinu [Dukla Heroes Street], into a modern four-room apartment with all conveniences. There my brother and I already had a children's room, there was also a large dining room, a den, my parents' bedroom and of course a kitchen and a room for the maid, which we had at the time.

We had a maid for a long time, when the second mother died, she was still there. We called her Fanca, I know that she was from Boskovice, by Brno, in Moravia. There were probably quite a few Moravian girls working as servants, and I know that they were treated quite well. With what she made working for us, Fanca for example built a house in Dablice.

The parents of my second mother, Marta, lived in the village of Kluky, by Podebrady. We used to go visit them often, almost every Sunday, because my father loved cars. Every little while we had a new car. I'd say that we were more or less middle class. We didn't own buildings, our father didn't want that. But we always had cars, every three years a new car. Our parents probably used to go on decent holidays, even though I don't even know how much they made a year. They would often go to the Tatras [High Tatras: a mountain range in Slovakia].

But my father always said that he didn't save money. Which was the right thing to do. He used to say that for a country's economy to function, money has to circulate. That was his motto. An absolutely modern way of thinking. And he also used to say as a joke that he wanted someone to marry me out of love and not for money. Back then people used to save up for girls' dowries. And he did the right thing, because he enjoyed his money. Then we lost everything anyways. He also equipped his dental practice with the latest. Had one of the first X-ray machines from Siemens.

I also remember my second mother's siblings. She had two brothers and one sister. I even know that one of her brothers was a university professor, Polak, and that at one time he lectured in Bratislava. I don't know his first name. The other one, also named Polak of course, was the director of some sugar refinery somewhere near Prague. Her sister lived in Podebrady; she was named Karla, was married or perhaps divorced, and was some sort of public servant. The siblings used to get together in Kluky, because the family was quite spread out. There were also perhaps some cousins, I don't know exactly any more.

In Kluky they had a beautiful garden, by this larger country house. From there I've got very intense memories of a garden full of flowers, of course with a swing and so on. We used to go to various nearby farms for fresh eggs... I remember these large, beautiful, grand farms, at least they seemed to be big to me. Apparently people used to bring food from there to Prague, and at the Prague city limits there was then a so-called customs checkpoint. Police, basically. And when you brought in food, you had to pay a tax. Which of course no one ever paid. I know how people would talk about for example having a couple of eggs with them, and said, 'I have nothing,' and everyone that used to bring in things then were terribly pleased that they'd brought in a couple of eggs. But it was more of a sport than anything else, just for fun.

I also remember - Grandpa and Grandma had a maid, I guess they weren't that poor - and she'd always go with me to the nearest forest, where there were dogs' graves. Apparently left by some local nobility, that I don't know. It was on the way out of Kluky, but not towards Prague, nor towards Podebrady, but on the other side. Before you get to Podebrady, there's a large graveyard there, then a turnoff towards Kluky, and if you took that turnoff and continued on, there were big forests there. And that's where those graves were. And not just one, several of them. Those dogs also had names there. For a kid it was an attraction. Back then it wasn't common, perhaps with the exception of some nobility and counts, to bury dogs. And these graves must have dated back to Austrian times.

Besides trips to Kluky to visit my second mother's parents, I also used to go to a guesthouse during the summer holidays, which was in Doksy. I was supposed to learn German there, but because it was all Czech children there, besides the German teachers, we spoke only Czech. It was by Mach's Lake, so I've got beautiful memories of Mach's Lake, where at the age of nine, when I was there, I probably learned to swim a bit, but I don't exactly know any more.

One summer vacation, I might have been nine, ten or perhaps eleven, we were in a different guesthouse, in Nadejkov, which is in southern Bohemia, whose owners were relatives of my first mother, by the name of Seger. They had a farm in Nadejkov, and during the summer there was some sort of camp set up there, where my brother and I were invited. Mrs. Segerova was probably my mother's cousin. They had two sons, one was older by about two years and the other by about four, one was named Milan and they called the second one Hansi, as he was named Jan.

I met Milan after the war during one reunion of children from Terezin. We were both amazed that we had survived. At that time he was already living in Israel, where he married Eva Diamantova, whom I remember from Terezin. It hasn't been so long ago that their son contacted me. He was terribly glad, and said, 'Finally I'll find out something about the Steiners again.' But I'll tell you, that I didn't have the feeling that he's some sort of relative of mine, by which I mean to say that it's not true that a person right away feels some sort of emotions. He'd already been born in Israel, and even though he speaks Czech, it very much depends on where a person grows up. Even though I'm always very afraid to succumb to some sort of false sentimentality, so I hold back from such feelings.

I have memories from the beginning of the war, and they're still quite sharp, because I wasn't brought up in the spirit of some sort of Jewish consciousness, and so it was something new for me at the time. Besides that, I was in puberty. Suddenly came this blow from nowhere, in the sense that the war was actually the beginning of a feeling, at first not completely conscious, but then of course more and more an intensely conscious feeling, that I didn't belong in the society that I lived in. They threw us out of school 12; we weren't allowed to continue. One prohibition followed another, I don't know exactly from what date. My father, who you could say was emotionally unstable, was breaking down more and more. I was suddenly in a situation where I began to be afraid of people.

The first impact was already before the war, when some little girl in Sokol yelled 'Jew' at me. I had no idea what she was going on about. We were an absolutely assimilated family, but it didn't come about through some specific aim, it came about due to our way of life. In my view it's very important that as long as people acted naturally, everything flowed from their way of life. Not that they said to themselves: 'I'll be this, or that.' Today there's a bit of a tendency for people to pretend, and not think enough. But that generation back then, and today it's seen as an attitude that's a bit naive in some respects, was convinced that their way of life was right, and that that's the way they should behave.

With the beginning of the war, I was alerted to the fact that people were watching us. Likely they were also the people across from us in the building - back then all the buildings in Letna had superintendents. They were usually from the poorer classes, although not all of them. As it's always been, envy also began. One prohibition after another was inflicted upon us, and suddenly I heard that we had to have a big 'J,' for 'Jude,' in our identification, that we can walk only in certain streets, and on streetcars ride only in the back car. To this day I always get on the first car, that's in my subconscious, and it's been a long time already.

As a Jewish family, we also had food coupons that were then in use designated with a big 'J.' We had smaller rations and could shop only during certain hours. Some shopkeepers used to bring my father groceries, as he was after all well-known and liked in Letna. I myself witnessed how surprised they were. 'Mr. Synek, those Jewish laws apply to you?' It was something incomprehensible for me. Here, during the First Republic, people didn't reflect on things so much as to say about someone that he was or wasn't a Jew. In a smaller town, or in Moravia and Slovakia, perhaps that was something completely different. I'm only talking about my experience.

I remember that a prohibition, or a bylaw came out - it was one of the first Nuremberg Laws - that the word jew had to be written with a capital J. That was something that I didn't understand at all anymore, I only understood that it was supposed to be pejorative. It had never been written like that before. I haven't accepted it to this day, here jew with a big J is used all the time, though I've asked in my articles for it to not be that way. Because I think that it's very, very wrong, because from that stem other things. Everyone uses only a capital J, but that's nationality, not religion, and why is it always taken as a nationality? [Editor's note: In the Czech language, jew in a religious context is written with a small "j," and Jew in the context of nationality with a capital "J."] It can't be used constantly.

In 1934 there was some sort of census, well, so a few people identified themselves as being of Jewish nationality, so then a capital J. Even the state is Israel, not Jew. And another thing, on our report cards, we had Israeli written for our religion, not Jewish. Or 'of Moses.' I'm very insulted by it, and I think that it supports anti-Semitism. It supports the notion that we're somehow isolating ourselves. Due to this I had big conflicts at the Prague community, even with Rabbi Sidon, with whom I'm otherwise on a first-name basis, as we were once co-workers. [Sidon, Karol Efraim (b. 1942): from 1992 Prague and national rabbi.] He knows it, and knows my opinions. The community also issues everything with a capital J, and that's quite important. Some would say, don't make a fuss, little j, big J, but that's not true. Big things are composed of small ones.

On top of it all, my father's dental practice was endangered, but then he got permission for only Jewish clientele, and thus I was able to work as his assistant. At that time everything had to be given away, musical instruments, pets, and as a dentist my father had gold. Well, I think that then he wasn't allowed to work with gold anymore, there were various substitutes. Then he could only do fillings, because he had to let the lab workers go, and only Mr. Porges remained, who was Jewish, and who went on one of the first transports. So then my father had no one left there, he had to do everything himself, and so could at most do fillings, but certainly not some sort of complicated prosthetic work.

I was helping him out, so I didn't go for any lessons anywhere like other Jewish children did, which I didn't find out until after the war. Maybe when they then met up and played together, it gave them strength. And that they had a bit of fun, even in the worst times there's fun, after all. But I didn't have any, I was in complete isolation. After I stopped attending school, my girlfriends from school of course never came by, people were afraid to associate with us. And that's something that I took very hard. My resistance manifested itself by my going about without a star 13. It made my father crazy and fearful, unfortunately I never got the chance to apologize to him. It was only later that I realized what he went through with us children.

Of all the prohibitions, the thing that bothered me the most was that we weren't allowed to go to school, and that the normal course of things was interrupted. It's not so much about the studies, but about the fact that you were suddenly deleted from society. You couldn't go to the movies, nothing. I didn't even mind the shopping, but the fact that I didn't have the possibilities other girls had. I didn't even have a substitute in another collective.

I remember how once my father arranged a visit - I think that it was somewhere in Dlouha Avenue, even that the people were named the Aschermanns, but of that I'm not sure - during some afternoon when people from Jewish families gathered. I went there, but it was completely foreign to me. I guess I was supposed to get to know someone there, but I was completely... well, I wasn't able to. Likely some patient of my father's saw me and said, 'Why don't you send your daughter, we're having a get- together.' I don't know, maybe it was someone's birthday. I don't know, I just remember that it made me all grouchy, and no one ever got me out anywhere again.

It was also back then during the war that my big complex began, because I said to myself that I don't belong among Jews, that I simply don't belong. My puberty played a role in this too. I wanted to be like other people, and it even went as far as me reproaching my father for my first mother also being Jewish, that I would have at least been only half and half. Later I regretted this terribly. Well, my father tried, explained, he was never angry with me, and was very calm. He tried to explain to me that it's not anything bad, and that when the war ends, everything will be different. I remember him telling me, 'The star you have to wear now, later you'll wear it as a badge of honor, it'll be like when the legionnaires returned from World War I.' He was deeply mistaken. Deeply. But thanks to this big complex, which I really felt intensely, I actually saved my own life.

Luckily, during the war my third mother lived with us, Anna Mandova, who married my father just before the prohibition of mixed marriages, so she put herself at great risk. What's more, her relatives tried to talk her out of it, understandably from fear for her future existence. She of course wasn't Jewish, but a Catholic, utterly tolerant. Overall, she was excellent, kind. According to me, a true angel. She'd loved my father for years; he used to care for her teeth, as a patient. My father was a very - so in this I'm not like him - handsome man, who didn't at all look Jewish. She was born on 9th March 1897 in Kolc, near Slany. She worked as a seamstress. She sewed normally, like people did at home, as well as for the Rosenbaum company. That was this large company where she apprenticed, and she was the first fabric cutter there. So she was a lady that knew what she was doing.

At the time when things were getting worse and worse, by then they were writing about my father in 'Aryan Struggle' - that was this seditious rag - and stars were being worn, he had some patients that were named the Kristliks, a husband and wife. They were faithful Christians, perhaps Catholics. They used to invite my father along with that third wife of his to this outdoor café somewhere in Holesovice, so that he'd be outside, and he'd walk around there with his star covered up, and they knew about it and weren't afraid. From Letna to Holesovice, that was actually the same quarter, and my father was very well-known, so it was a risk.

This couple had such an influence on him that he began to engross himself in the Bible. He read both the Old and the New Testament, and had the Bible on his nightstand. In those last years it apparently helped him very much. What exactly he read from it, I don't know, but he needed some faith, and in that case it doesn't matter which one. It's a question of a spiritual crisis, and he was of a less stable nature. He was very sensitive, very sociable and on the other hand used to have depressions. That was all caused by the way of life during that time. I think that in order to last it out, he needed to believe in something. I don't think that his Christian wives played any role in his affinity to the Bible. Neither of them was religious, I don't remember them going to church. My father even had a baptismal certificate, it was issued to me and obviously him too by the priest at Strossmayer Square. Back then we thought that it would help, but it was of course useless.

But only a handful of people helped Jews. I'm not accusing anyone, I'm stating facts. And when I then add it up, all that had its role in the fact that those people then had a harder time standing up to the hardships that followed. Up till then my father had been extremely sociable, he was a successful dentist and sometimes even lectured about it, and was constantly studying it. So that he'd constantly get better and better at it, so he devoted himself to it scientifically as well. Now, suddenly, when everything was supposed to come together and bear fruit, everything collapsed. Of course, he was marked by the deaths of those two wives of his. My childhood was influenced by those deaths as well.

Suddenly the fact that we were Jewish was an issue. No one had concerned themselves with it before. No one had even known that my father was a Jew, he had nothing Jewish in his appearance, and even the name is Czech. In fact, when he first remarried, he also married a dentist, a non-Jew, who however looked a bit Jewish, so his patients would say to him, 'Why, Mr. Synek, you've married a Jewish woman?' Not until right before the occupation, when papers like 'Arijsky boj' [Aryan Struggle, a magazine put out by the Czech fascist movement Vlakja (Flag)], then we were. Suddenly my father was 'That Synek Jew.'

At that time we were living under great tension. There was constant tension in our home, because not once, but several times someone rang at our door - I remember for example one Czech policeman, who was apparently high- ranking, who walked through our apartment and pointed out paintings that my father then had to give him. Besides this, we were always afraid of Germans and of informers, because in the newspaper belonging to the Vlajka movement 14, that was this Czech fascist rag, there were various denunciatory articles about my father. Like why is it that Mr. Synek is fixing teeth, and so on. So we lived in fear and tension, and you can say that my father was a nervous type, and that it of course rubbed off on me.

I turned to books for some sort of consolation, and already back then I was writing these little verses, I was 13, 14 at the time. I read only poetry. I read prose only a bit. I was very influenced by literature, maybe even of a somewhat exclusive type, especially for my age, which my brother, who was five years older, used to give to me. During those times all he was doing was reading, he was as opposed to me very single-minded and was gathering knowledge. For him it was also actually his future profession. He concerned himself with words, and so did I, but in a different way. He was an example for me, but of course we also fought. He used to scare me at night in that children's room, with lights and so on. So sometimes I hated him. But he influenced my reading, and with my affinity for poetry I was then this insufficiently realistic person. My thoughts were influenced by a certain dream factor, the non-acceptance of reality. This conflict was very, very strong in me.

I was very influenced by what I read, for example already when I was very young I read Pitigrilli [Segre, Dino (1893 - 1975): pseudonym Pitigrilli, Italian author]. I know that a scene when some woman was receiving her lover in a coffin had a great effect on me. To this day I don't know what it was called. I'd really like to read it again. And then there was the famous book by the Italian author Amicis [Amicis, Edmondo De (1846 - 1908): Italian writer and journalist], 'Heart' it was called, and it contained stories over which I wept many evenings and nights, because they were terribly sad and beautiful. I'd like to read that one again too, for one. There was for example one story, 'Sardinian Drummer,' about how during some war they shot a 12-year-old little boy, who crossed some terribly high mountains in Italy, I don't know where exactly, to find his mother, who had cancer and had been transported to the other end of Italy. I was completely kaput from that.

Then I was influenced, for example, by reading classical Czech literature, beginning with Nemcova 15. I liked it all, Jirasek for example [Jirasek, Alois (1851 - 1930): Czech writer and dramatist]. To this day I think that by making him compulsory school reading, they've discredited him. Those classical authors knew their craft, there's magnificent use of words there. I remember that the only book that I took with me to Terezin was Macha 16, his 'Maj' [May]. Nothing else. I liked it very much.

Back then it was in general a little different. In my youth, though after the war already, it was in fashion to read Dostoevsky 17 and carry the book so that others would see it. Now it's music. That's about something completely different. Back then that didn't exist at all, when you wanted to come across as an intellectual, you had to know literature. Right after the end of the war, I was already reading 'The Castle' by Franz Kafka 18, published by Manes in 1936-1937, and was very influenced by it, even though I didn't understand it very much.

My father was also a big reader, but certainly not of poetry. He read Pritomnost 19 magazine, which was edited by Peroutka 20, that was really for intellectual readers. It was a monthly with a beautiful yellow cover. I remember the way the cover looked to this day. When during the war we weren't allowed to go out anywhere in the evening, our father used to read to us. Well, there was no TV. I remember that he was reading the novel 'Katrin vojakem' and 'Katrin svet hori,' which was about World War I. It was dramatic. He'd read us a bit after supper, and we'd sit quietly. He used to do that mainly after the death of our second mother, because he was terribly depressed, lonely.

We used to subscribe to a lot of books from the ELC, a modern European literary club. [European Literary Club: was created in 1935 on the initiative of the publishing businessman Bohumil Janda (1900 - 1982) and his brother Ladislav Janda (1898 - 1984).] Besides Pritomnost, he also subscribed to other papers, Rozvoj, which was a paper that belonged to the Czech-Jew Association. We used to get those papers, but I didn't read them, not Pritomnost either. I wasn't at all interested in that, because they were political, and let's say partially philosophical and cultural articles.

During the war

In 1942 my brother got a summons to the transport. Alone of course, because our father was protected by his marriage to a non-Jew. But he didn't get on, and left a letter that he'd committed suicide. Then very uncomfortable situations followed, because we were in contact with him and I was the connection. Either I or my stepmother would bring him things that he needed. It was so terribly risky. Everything was full of fear and risks. I think that that atmosphere of fear molded me for the remainder of my life. From that time I've never been far from states of anxiety. I don't want to say depressions, that's a strong word. They were more like states of anxiety. Fear of the unknown.

Later I realized that it predestined me to this, basically constant, mild misunderstanding with the world as such. To questions why I am, why do I do this and why do people do that. It's this feeling that I can't communicate what I'm feeling anyways. Basically not to anybody. And that I have to come to terms with that constant misunderstanding.

I've got this incident, completely abstract, just to explain it more closely. In that apartment on Letna, where I lived, to get to the room where I slept, you had to cross from this large room where we used to have supper, through this quite large front hall. The light switch for that hallway was completely on the other side. So that I had to cross it in darkness. To this day I've still got an intense memory of sitting there and being unable to go to bed. No one knew about it, I of course didn't tell my father about it. I remember that I exerted all my energy, or strength - it's more of a symbol, what I'm saying now - to walk through that dark hall. When I entered the children's room and turned on the light, I was completely exhausted. I think that this extreme exhaustion from that journey, which today in my reminiscences is so short, but back then seemed unimaginably long to me, is a symbol of my entire life.

This fear-filled period lasted up to December 1942, when I myself was summoned to the transport. That's when I saw my father for the last time, he had completely collapsed, because there was nothing he could do. Even before that he had been living under terrible tension, in terrible fear, and then suddenly... For him I was a little girl, even though I wasn't all that little any more. Certainly he also blamed himself for everything. Because he was so extremely just, so absolutely humanistically inclined and he idealized the world - even though back then it was still possible, today I don't idealize it anymore, and I don't think I'm alone - that he still believed that it wasn't possible for Czechoslovakia to be gone and for the Czechoslovak state to not care for its citizens.

There was this one incident that took place, that after the Anschluss 21, after the annexation of Austria, some distant cousin of his arrived in Prague, who was then continuing further on. He was at our place, and telling us about the horrors that were taking place there. Well, and when that cousin left, my father said, 'That's not possible. He must be crazy, he needs to go to a mental institution.' He didn't believe it, he didn't want to believe it. He wasn't alone in that, it must have been utterly horrible for those people back then, that powerlessness. What's more, back then a man was still the head of the family, who takes care of his family members. That has changed a bit, after all.

You see, before the war I had had the possibility of emigrating, but my father didn't let me go. When I was very small, when that first mother of mine was ill, I had had a nanny, Miss Saskova. This Miss Saskova, that was around 1939, left for England to work as a nanny for some family, also some dentist. She apparently liked me in some fashion, and so came to see my father, that she could take me with her and that I'd learn a trade there. My father said that it was out of the question.

I remember that even later there was always talk of emigration around us, but we didn't have any contacts, it was said that certain Jewish families had a lot of money and information, so they had at least some possibility of emigrating. Often it was a question of money. I don't know anything exact about it, just that very few people got an affidavit. They may have had one promised, for example, but then it never happened. I know that the Petchka family was terribly rich. They even transported out all of their employees, an entire train. But I'm convinced that even if someone had offered my father something, he'd have turned him down.

We for example didn't even know about Winton's 22 activities, how he transported out Jewish children. We didn't find out about it at all. It's true that we weren't in very close contact with the Prague Jewish community. But maybe it wasn't just because of that. We were recorded there. Jews, for example, used to get summons, while they were still in Prague, for the clearing away of snow. Well, that we used to get every little while. My father and brother. That was so humiliating, you'd be shoveling snow, wearing a star, and on top of that people would be yelling things at you. It was always terribly difficult to get out of it. It was a so-called compulsory labor. So we were in the records.

I expected the transport, I knew that it would come, and was afraid. When I then got the summons, I knew that I had to go, that I couldn't do what my brother had done. For a week before they took us away, we were in a so- called quarantine at Veletrzni Palace [The Trade Fair Palace, a Modernist 1920s exhibition hall]. I knew that my father was only a few buildings over, but with that star he couldn't even come see me. But he sent someone, because through some guard I got a box of candy with a letter.

The conditions were quite bad for us in the Veletrzni Palace. I ended up with a fever from it all. At that time an excellent person took care of me there, Gustav Schorsch, who unfortunately never returned. By complete chance, he had the number next to mine. The transport was named 'Ck,' and I had number 333; I guess the threes were 'lucky.' When you entered the quarantine, there were mattresses arranged there according to those numbers. Schorsch saw me there, that I was alone and crying. He helped me very much during that week before they transported us away, and also the whole time in Terezin, until they sent him further on.

When he knew that I was sick, or that something was wrong, he'd always come to check on me. He used to put on plays there, gave lectures, and in general was culturally active. He was a lot older than I was, nine years. He'd already graduated from high school, and as a student had already acted on the stage. He was the founder of Theater 99 on Narodni Avenue. He was an exceptional stage talent.

After the war a book about him came out, 'Nevyuctovan zustava zivot.' After the revolution 23, in the 1990s, I among other things also wrote a script about him. The film exists, and was shown on TV. Unfortunately I was only able to use interviews with other people, his photographs exist, but there was little authentic material, except for some plays he'd dramatized. They've even been put on at the National Theater. He was an exceptional person, a lot of people reminisced about him, his former classmates and so on.

I don't exactly know what went on with my father after my departure. I think that someone there helped him, that someone from those Letna residents, either from his former patients or the businessmen there, used to go to see him. All the business owners there knew each other. I think that my father must have had contact with someone, because during that year that I was in Terezin, he managed to smuggle through a letter, apparently via the Czech policemen that guarded us in Terezin. I've got it hidden away to this day. It's beautiful, full of hints. He wrote 'Jirina is all right,' that was my brother, Jirka. Contact with my brother was then apparently maintained by our stepmother. But both she and my father were arrested about a year after me. He had the dental practice right up to his arrest. Then there was apparently some German there, because after the war all the equipment was still there. When we returned, my stepmother rented it out via a so-called widow's law.

In Terezin I wasn't all alone anymore, some sort of society formed there. The people there were in the same situation. When I arrived there, we were in the so-called shloiska, which is a quarantine. [Editor's note: the Hamburg barracks, so-called shloiska, likely from the German 'Schleuse': women's accommodations, and from 1943 especially for Dutch prisoners. At the same time the main transport dispatch location.] We had to report there, and precisely because of the horrible complex of mine that I was something different, I reported that I was a half-breed. I had no idea that this had been the first transport that had contained half-breeds, otherwise I would have been found out, and I wouldn't be sitting here now. It was a completely irrational thing. It seems like I've made it up, but that's really how it was.

After some time in Terezin I was put in the children's home. There were children from about 11 or 12 upwards there, up to about 15 or 16, I think. I don't know exactly. I was among the oldest ones there. Younger children were with their parents. For example, my husband, who's younger than I, was with his mother. Children that had arrived in Terezin with their parents were also in the children's home; I was more of an exception, I mean that I had arrived alone. But my uncle, my father's brother, was already there. He was lying there in this hospital room where people with tuberculosis were. I used to go see him occasionally. My father's father was in Terezin at that time. He died very early on, and then my uncle as well. That was in 1943. I didn't have any other relatives there.

In Terezin I became friends with Vera, back then Bendova, who was also a half-breed, but a real one. We were bunkmates - there were triple bunk beds, and we slept up on the top bunk together. She was the only one who knew the truth about me; I had to tell someone what the case was with me. Always, when I was summoned - half-breeds used to be summoned to the headquarters - neither of us slept. We're of course in touch to this day. She lives in Olten, Switzerland, where I went to visit her after the revolution.

As a half-breed I was allowed to stay in Terezin; it protected me from further transport. And my best friend as well. Of the people in our room - we lived in No. 29 in L410 - mostly everyone else were transported further on. And some returned after the war, and some didn't. Plus when Brundibar 24 was being put on there, new children had to be recruited to replace the ones that had been transported away. I myself never played in Brundibar, as I never knew how to sing.

We then tried to put on a play by Klicpera with Schorsch. But mainly I wrote. These trifles, various poems. Mostly they involved reminiscences, for example about a girlfriend that had remained in Prague, or laments over what I had lost. There were all these sentimental things, with tendencies towards romantic expressions. Not long ago there was a reunion of girls from Terezin, and they said, 'Listen, we were always thinking about food, and you were writing poems. We used to say to ourselves that you aren't normal.'

I of course also experienced love in Terezin. And not just once. I think that I fell in love there at least five times. I never counted the times, and I always also soon got over it. It never lasted very long for me, which was still the case long after the war. I perhaps stuck out a bit in Terezin; I was completely blond and blue-eyed. Maybe it also says something about that period, it was sometimes for only a couple of days, but intense.

However, there were one or two stronger relationships. Not one of them returned. One was named Jiri Kummermann. That boy, though he was 17, was already composing. I've still got some notes, some fragments, hidden away to this day. His mother, a former dancer, was also there; she didn't return either. Because I knew that I'd probably stay in Terezin, I had some of his notes with me. But after the war I gave them to his relatives. I guess that the relationship was quite intensive, because long after 1945 I still thought that he might appear.

Then there was Karel Stadler, who I knew from Prague, because he was a friend of my brother's. An exceptionally educated boy. He was about four, five years older, while the musician was the same age as I. So I was impressed by him, and felt embarrassed, that I was completely dumb compared to him. I wasn't the only one to fall in love there. Of course, during the day we couldn't see each other much, but curfew wasn't until after 8pm, so we could still be outside in the evening.

Terezin was an amazing education for me. First of all, I wouldn't be the person I am now, but that's normal. But mainly I was introduced to values there that I would never have had the chance to know. For example what friendship can do for a person, but not only that. How important the influence of art is. There, the people that had come to Terezin, and they were professors, artists, all of them truly tried to convey what they knew. There's no way that could happen in a normal situation. In Terezin everything was extreme, it wasn't a normal situation there. That's of course hindsight, back then I couldn't have realized it.

We lived through extreme situations there. For one, there was the fear of further transport. No one knew when he'd have to leave, and where to. Even though no one of our generation of course wanted to at all allow the fact that it could be the end. Almost to the end of the war, I didn't know that the gas chambers existed. That was because I was in Terezin. Maybe someone there knew it, but I think that most of them didn't. Not until 1945, when people were returning.

Understandably, we also had fun in Terezin. And those love affairs. Everything was experienced intensely, because there you couldn't count on having time. I think that whether you're an adolescent, or 20 or even 50 years old, that's a very unusual situation. There you didn't at all have the feeling that time was uselessly running between your fingers. The intensity of the time was also given by the fact that we were hungry. Everything was intense. I never experienced such intensity before, or since then. Everything that those children were doing there, either they were drawing something, or writing, was full-on. The entire leadership tried to do as much as possible for them. Because in their view the only ones that had a chance of survival were the children, or the young people. In the end it wasn't like that, but even so, they tried.

I don't know if some country, or some group, some small nation, does in a normal situation as much as was done back then in those extreme times in Terezin. Back then, everything was at stake. It was also necessary to help the adults as well as the young people, to make them aware of the fact that they have to watch themselves so that they won't decline morally. All that was terribly important. You had to preserve the feeling that you're not in some hole.

The question, why did I return and not someone else, this feeling of guilt, we've probably all got it. That's been reflected upon many times already. I of course don't have an answer to it, and you can't even feel guilty. But I think that the percentage of those best ones that didn't return is very high. You also don't know what those children would have become. Certainly there were many talented people there, and with that experience, that intensity that I've talked about, everything was amplified even more.

What do the people that survived have in common? I don't have a definite answer to that. I think that the majority of the people that returned are today much more tolerant than people without this experience. But it of course also depended on what sort of way of life you ended up in. That also molded you. If you remained completely alone, or if at least a bit of your family remained. Its way of thinking and intellectual position. Life itself.

There are all sorts of people. Lots of them moved away as well, and those, when they come here, are also completely different. But there is something there, some sort of common fate. Not that we're extremely close, but there is something there that I can easily and immediately identify with. With someone who didn't go through it, I'd have to do a huge amount of explaining to give them an idea what it's about. Here I don't have to. There's no doubt that we have a common experience, which binds us. It's hard to say, maybe we're connected by some sort of reappraisal of values. A larger degree of tolerance, that for sure.

Of course, there are some individuals that don't fit the pattern, but even now, when I meet with people, it's clear to me from the first moment who is a survivor. I also think, though maybe I'm fooling myself, that those that survived won't succumb to concerning themselves only with economic matters. I think that they're a little less susceptible to the influence of today's way of life. That they're a little more themselves. There is, after all, something there, some experience that sets them apart. If I was to summarize what my stay in the concentration camp took from me, it took my past. That severing of the past, that's something I have to come to terms with.

We were terribly looking forward to returning home. But of course there was no place to return to. I suddenly didn't know what to do. How to live, why at all, and mainly there was no one to turn to for advice. My brother, who also survived, didn't pay much attention to me, he had enough of his own cares and worries. He was running all over the place, they were already starting up a newspaper and he was given an important editorial position, head of the cultural section. They got what was then a German paper, Mlada Fronta 25, and he was basically a founder. He was 23, and J. Horec, later the editor-in-chief, was I think 24. [Horec, Jaromir (b. 1921): popular Czech poet, writer, journalist and publicist] He had absolutely no time for me. I remember that back then after I had returned, I went to report to something like the people's committee of the time, I don't know what it was called anymore, because I needed identification. There they gave me two pieces of underwear, panties and some sort of nightie, and about five handkerchiefs.

My father didn't survive the war, he died in 1944 in Auschwitz. I've got two dates. One is in February, the other is in May, no one knows for sure. They arrested him in the fall of 1943, he passed through Karlovo namesti [Charles Square], where he was interrogated, through the Small Fortress 26 to Auschwitz; he didn't go on a normal transport. He was most likely arrested because of my brother. My stepmother was also arrested, but she returned after the war. But she also didn't know why they actually arrested them. It's quite likely that they were denounced by someone. She passed through the Ravensbrück 27 and Barth concentration camps. [Barth: camp that fell under the Ravensbrück concentration camp] She didn't return until somewhat later, not until the end of June 1945, and was seriously ill.

Post-war

After the war, I supported my mother as much as possible; after all, it was thanks to her that I saved my life, because they didn't know that she wasn't my true mother. If that would have been uncovered, it would have been the end. She died when she was 85, that would be sometime in 1983, because she was born in 1898. She was hit by a streetcar; she became disoriented and the streetcar hit her in the head.

By the way, I've found out that in the Pinkas synagogue, where the names of the dead from the concentration camps are, there is also my brother's name. [Editor's note: during the years 1992 - 1996, 80,000 names of Czech and Moravian Jewish who had died at the hands of the Nazis were written by hand on the walls of the synagogue.] Like as if he was dead. As I've said, when he got the summons to the transport, he left behind a letter that he'd committed suicide, and disappeared. In the register he's listed as being dead. Well, there's nothing we can do about it now, it's there. According to one tradition, that mean's he'll live a long life.

Other mistakes occurred as well. For example, my father was arrested, he didn't go by transport, but nevertheless also ended up in a concentration camp, and didn't return. But he's not in the Terezin book. [Editor's note: the Terezin Memorial Book contains the names of Jewish victims of Nazi deportations from Bohemia and Moravia during the years 1941 - 1945.] I don't know if his name was added later, I haven't tried to find out. I told Mr. Karny, who put that book together with his wife, that he's not in there, but that he also died in Auschwitz. There are other similar cases, people that didn't go via the normal transports, but were arrested or disappeared like my brother.

At first I lived with my brother, who got an apartment on Letna, and then, when my stepmother returned, we moved into the apartment where the dental clinic had been. But nothing except for the dental equipment remained there. Back then, when I returned from Terezin, I was, above all, hungry. My mother had relatives here, a sister who was very kind, and I used to go to their place in Smichov for lunch. They fed me from what they had for themselves. It seems strange, but I don't think that there was any sort of organization to take care of those people that had returned. It never occurred to me at all to go to the Jewish community. Maybe I should have gone there, they would definitely have given me advice. After all, there was some assistance here, as I found out later, from America 28. Some applications for compensation were being submitted. Well, I didn't know anything about it, and got nothing. Not until now, after the revolution, that which everyone has.

For about the first two years, until I got my bearings, I really didn't know how I should behave. I knew that you should say hello to people, and what I should say when I enter a shop, but I couldn't at all grasp other people's way of thinking. They were all foreign to me. I had no idea how they thought, why for example they would do something they did. I always wanted to know the reasons for people's behavior.

For example, my aunt, the one that had divorced my uncle because of that publishing house, wasn't Jewish and survived the war. After the war she was in charge of the bookshop that belonged to that publishing house. She offered me a job selling books there. So I worked there for some time. Then she told me, 'Your waist isn't slim enough, I'll buy you a corset.' I couldn't grasp it at all. Why I should be selling books there, and why she was going to buy it for me. I should have asked her, why would you buy this or that for me, or why should I be selling books here? I'm sure she would have explained it to me. But I didn't ask her.

Or another example. There were some girls from Terezin on Letna, and they pulled me into the Youth Union 29. Again, I used to go there, and didn't at all know why I was even there. There were many things that I didn't get back then, not until I met a girl my own age, whose father was a dentist, a colleague of my father's. Dr. Vanecek. He invited me over to their place, and gave me money. That Vera was the only one to say, 'You've got to go to school.' If it hadn't been for her, I would have said to hell with everything. But even she had to explain to me why I had to go to school, and even so I didn't completely understand. Maybe I was completely neglected, or maybe more likely, lonely. I think that it was due to loneliness. And yet later in life, I was a sociable person and not an introvert. But all too late. But back then I was definitely a complete introvert. I think it's a consequence of that what I've talked about, that severing of bonds with the past.

Luckily, several relatives gradually appeared who also helped me. For example my first mother's cousin, who had a list of people whom Anna, my first mother's sister, had hidden things with. He made the rounds of those people with me, who for the most part didn't want to return anything. I experienced this very unpleasant situation, when they'd say, 'Oh my, you've returned!' I don't even feel like talking about it. What's more, that's common knowledge. As far as school goes, they explained to me that I had to arrange a stipend. From a financial standpoint, our life after the war was very bad indeed. In the end I was only able to finish my studies thanks to that stipend, which I got as a war orphan. Back then I was being paid by the War Reparations Office. I think that it was in Karlin [a Prague city quarter]. Without that money, I wouldn't even have had money for a slice of bread.

My brother had managed to graduate from Jirasek High School before the war, and after the war he registered at the Faculty of Philosophy. In 1947 he was sent by the then Ministry of Culture to Paris, where he published a weekly about Central Europe named 'Parallele Cinquante,' Fiftieth Parallel. He was supposed to return right after February 30, he was there for one year. But he emigrated and remained abroad. But he was here secretly, and thanks to my boyfriend at the time, the artist Jiri Hejna, whom I was with for a long time, we changed the stamp on his passport with the use of some plaster. So he got out once February had already passed.

I began attending university in the spring of 1946, when it was actually first being reopened. I picked the Faculty of Journalism at the University of Political and Social Sciences. It was composed of three faculties: political, social and journalistic. This school was also intended for future diplomats, that is, the political and social faculties, not the journalistic one. Already as an adolescent I had written poems, and during the war as well. Besides movement, dance, my strongest interest was literature, so that meant that it had to be some school where you worked with words. I imagined that afterwards I could perhaps live in some foreign city and be a correspondent. In Paris, for example. Stupid me. The faculty of journalism was something new. I've got this impression that it didn't exist during the First Republic, but I'm not sure. It was probably possible to study journalism someplace else, that I don't exactly know. But for me it was a novelty. Plus I knew that there they wouldn't require me to know Latin. I was afraid that even in that Faculty of Philosophy, I'd feel the lack Latin, or perhaps Greek.

I actually finished my high school as part of that faculty. Back then that was possible. This school had a solely practical focus. There was a lot of economics and law, something from all fields. I don't know if that was good, but to me it seemed a lot more doable, because I was missing entire years of education. I thought that I had a better chance of managing it. There was no problem getting into the faculty, everyone that registered could attend. Back then older people registered too, who for example hadn't been able to study during the war. But there was a lot of filtering out. Few people finished all four years plus a thesis. Those people perhaps went for a more practical life, or they didn't like it.