Anna Schwartzman

Anna Schwartzman

Chernovtsy

Ukraine

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of interview: June 2002

My name is Anna Yakovlevna Schwartzman. I was born on 14th January 1923 in Kishinev, Moldova. At that time Moldova belonged to Romania. My maiden name is Barenboim, and the name my parents gave me at birth is Hannah.

My father, Yankel Barenboim, was born in a Moldovan village in the 1880s. I don't know the exact place where he was born. His parents died long ago. I know this because my oldest brother, who was born in 1911, was named Khuna in honor of my deceased grandfather. Since it's customary for Jews to name their children after dead relatives, I can state with certainty that my grandfather died before the birth of my brother, that is some time in the early 1900s. My grandmother died even earlier. I don't remember anything about them. If my father did tell me about them, then none of it was preserved in my memory.

My father had one brother and seven sisters. Five sisters lived in Kishinev, and I knew them and their families. Two of my father's sisters, Tuba and Beylia, and their brother, Moishe, went to America in the 1910s. My father used to correspond with his sisters but lost touch with his brother. After Moishe left for America, nothing was heard of him again. I know that Tuba and Beylia were the oldest children in the family, and Moishe was slightly older than my father. I can't recall anything about the life of the sisters that left. Of course we received letters from them, and my father read them aloud, but I just don't remember any more.

I don't remember the dates of birth and death of any of my father's brothers or sisters. Yentl was the oldest of the sisters who lived in Moldova. She was married, but I don't remember her husband's name. They had three daughters and one son. The second oldest sister was Leya. She had five children: two daughters and three sons. Her husband was a tinsmith and called Srul. Then there was a sister named Dvoyra, whose husband's name was Iosia. He was a businessman. They had a daughter named Khovele. The next child was my father, and after him there were two more girls. Rukhl and her husband ran a tavern that sold wine. They had four children: three sons and a daughter. The daughter was named Zina, the oldest son was Khuna, in honor of my grandfather, the other boy was called Shimon and the name of the youngest I'd forgotten. They were all older than me. The youngest of my father's sisters was Tzipa. Her married name was Rozenshtein. Tzipa's husband had a grocery store. There were three children in their family. The oldest daughter, Paula, was three years my senior. We were friends. Today Paula and her son live in Brooklyn, New York, USA. Paula's younger sister was named Enna. She was two years younger than Paula. Enna lives in Israel. Sometimes she calls me. Paula's older brother David, lived, in Israel. He died almost ten years ago.

My father's family was very poor. He used to say that the children often went to bed hungry. Their mother was always concerned with feeding such a large family, she worked around the house unstintingly. Clothes were passed from the older kids to the younger ones. The biggest problem were shoes: in the summer everyone walked barefoot, and in the winter children often stayed in because they all had to share one pair of boots.

My father and his brother attended cheder. In the winter they had to take turns, again, due to the shortage of footwear. The children learned how to make an imitation of a bast-shoe from the stem of a corn plant. Needless to say that these shoes didn't keep them warm, but it was possible to wrap ones feet in some rags first and then put on these pseudo-shoes.

My father said that his parents were religious people. My grandparents attended the synagogue. Before Sabbath my grandmother lit candles at home. They celebrated Jewish holidays. My father didn't tell me any details. The family spoke Yiddish at home and Romanian with their Moldovan neighbors. Romanian was the official language in Moldova. My father hardly knew any Russian.

Neither my father nor his sisters wanted to spend their entire lives in poverty in a small Moldovan village. The children grew up and, one by one, they left for the capital of Moldova, Kishinev, in search of a better life. My father left, too. He had no education. He found a job as a construction worker and rented a small place to live. I know very little about that period of his life.

My mother, Molka nee Kritz, was born in 1889 in a small village in Podolskaya province. That part of Ukraine borders with Moldova. Her Romanian was poor, and she preferred to speak Russian. My grandmother, Sura Kritz, was born in the 1860s, but I don't know where. I hardly knew her. She died in 1926 when I was very young. I have blurred memories of my grandmother. She and grandfather used to come over to our house. I remember that she had beautiful hair: dark, wavy hair arranged in a heavy knot at the back. Later my mother told me that it was a wig. My grandmother wore white blouses and long dark skirts. I know that she suffered from a weak heart. My grandfather, Solomon Kritz, was born in the 1850s, but I don't know where either. In the early 1900s their family moved to Kishinev. My grandfather worked while my grandmother ran the household. I knew my grandfather well because I spent my childhood close to him. He never remarried after my grandmother's death in 1926. My mother took him in, and he lived with our family until he died in 1933.

My mother had three brothers, and they were all older than her. They all left for other countries when they were still very young. The oldest, Khaim Kritz, went to America in 1905. They kept in regular contact with my mother. Khaim was a tremendous help with money. I don't remember what Khaim did. He had two kids: a son and a daughter. After World War II, when my mother was no longer alive, the correspondence ceased. I don't know what happened to Khaim and his children.

My mother's second brother, David Kritz, lived in Palestine. He left in the 1910s. David got married in Palestine and had two boys and a girl. My mother's youngest brother, Zeilik Kritz, lived in Poland. On his arrival there he worked in Gdansk, a port town. Later he got married and moved to Warsaw, the capital of Poland. He had one son, Milya. Zeilik often wrote to us. I remember the last letter, which we received in 1939. He wrote that his son had decided to go to Palestine, and that he would come to meet us and say goodbye on his way there. We were all very excited by the forthcoming visit of our cousin, but then the war began in Poland. We have not had any news from Zeilik or his son ever since. I believe they both died during the Holocaust.

I don't know how my parents met because they never talked about it. They got married in Kishinev in 1909. They had a traditional Jewish wedding with a chuppah. My parents were religious, just as their parents were.

My parents rented their first apartment. I remember that apartment. Our family lived there until 1932. There was a large courtyard with a flowerbed in the middle. There were a few separate small houses in the courtyard. They all belonged to a single owner, a middle-aged Jew, who rented them out. Each house had two rooms, a kitchen and a vestibule. There was no bathtub and no toilet. We had no running water. Water was brought in from a well and stored in a large barrel, which stood in the kitchen. We bathed in the kitchen, in a large galvanized trough. The water was heated in a samovar and poured into the trough. The toilet was in the yard.

After the wedding my father continued to work in the construction business. My mother did all the housework. In 1911 they had their first child, my brother, Khuna. Later, after Moldova was annexed to the USSR in 1940, he was known as Yefim because this name has a more customary Russian pronunciation. In 1913 a girl was born. I don't know her name. When she was 2 she contracted some childhood disease and died in hospital. After my sister's death my father was grief- stricken. He visited the cemetery daily, painted the fence around her grave, chiseled letters on the headstone and painted them. My mother said that he had forgotten that he had a family. In 1916 my brother, Ruvim, was born. I was the last child in the family. After my birth, my father was finally able to stop grieving so much over his dead daughter.

There were mostly Jewish families in our courtyard. Moldova belonged to tsarist Russia until 1918, so there were Russians who remained there, but there was only one Russian family in our courtyard: a married couple and their three kids. The youngest of them, Artiusha, became a close childhood friend of mine. My childhood world was our yard. We had a few walnut trees and a large, white acacia. Artiusha and I played in the shade of the tree. All the other children in our yard were much older than me. They didn't pay attention to us. My father created a small sand mound for us to play, and Artiusha and I spent days puttering about in this sand box. In bad weather we played either in his house or mine.

When I turned 4 my parents sent me to a Soviet kindergarten next to our house. There was no necessity because my mother didn't work, but I wanted to be with my peers. We were in kindergarten until lunch time. The children and teachers played different games, we made figures from putty, listened to fairytales read by our teacher and sang songs together. In good weather we played ball outside. We used to take sandwiches and fruit with us from home, and at 11 o'clock we had breakfast. The kindergarten stayed open until 1 o'clock. After that we went home and had lunch. The kindergarten was full of kids of all ethnic backgrounds - Jews, Moldovans and Russians. We all lived happily together. There were no differentiations because of nationality. Everyone spoke Romanian. It has been my second native tongue since my childhood. [The first one was Yiddish.]

We lived modestly. Only my father worked, and he had to support my mother and three children. We had no additional source of income. Farming land was outside the city, and we lived in the center. Kosher milk and dairy products were brought to us daily by a Jewish woman from Roshkanovka, a suburb of Kishinev. In those days each family had their own dairy supplier. It was customary in Jewish families for the wife not to work. She had to work at home. This was even an advantage. There were no refrigerators back then, so in the mornings the wife would go to the market, buy fresh products and make lunch. At lunchtime her husband would come home to eat.

Children returned home after school. By the time we came home, my mother always had fresh and delicious food ready. In the evenings, after supper, we went for a walk. Back then it wasn't like it was when I had my own family: you came home from work and had to make lunch for the next day. Back then a housewife would go to the market and buy everything that was needed. Vegetables and fruit had to be fresh every day. In Kishinev, fruit wasn't sold by weight, it was measured by basket. My father would bring a basket of white grapes, a watermelon, or a melon in the morning. Apples, pears and cherries were sometimes sold by the kilo but more often by basket or bucket. There were good harvests in Moldova, especially for grapes. My mother usually bought meat and fish at the market. She had her own butcher and her own fishmongers. Every seller had his own clients. Butchers were usually Jews, fishmongers usually Russians. And fruit, grapes and dairy products were brought by the Moldovans. My mother always went to the market in the morning. If a woman went to the market after lunch she was deemed a bad housewife. To this day I detest food from the refrigerator. Even today my fridge is unplugged. I go to the market every day. I cannot carry much so I only buy a little, but it's fresh every day.

Our house was immaculate. My mother liked to grow flowers in bowls. Our windows faced the street and on our window-sills we had such beautiful plants that passersby used to stop to look at them. Mother cooked on a kerosene stove. We also had a large furnace stove in the kitchen, which was heated with wood. Usually my mother would light it when she baked challah or made food for Sabbath. She prepared Jewish dishes. She would leave pots with chicken broth or stew in the oven overnight, and the next day they were still hot for lunch. On other days she cooked on the kerosene stove because kerosene was cheaper than wood. She would put a tripod over the stove making it possible to put two or three pots onto it at the same time. The noodles were always homemade, mother made them.

The rooms were also heated with these stoves. In the summer we stored wood for the winter. Coal wasn't used for heating in Moldova. In order to save wood, we bought corn stumps. They burned fast but cost next to nothing. We would put a large log in the furnace and then add the corn stumps, to keep it warm.

Our family was very religious. My parents went to the synagogue every Saturday. The synagogue they went to wasn't the only synagogue in town. There were five or six of them in Kishinev. I don't remember the name of the largest and most beautiful synagogue there. There was a big synagogue with a choir and that's what it was called, the 'Big Synagogue'. The 'Big Synagogue' was attended by our whole family. My parents had their own seats there. The majority of the Kishinev Jews had their own seats in the synagogue. These seats were purchased. When my grandfather moved in with us after grandmother's death, he also started attending our synagogue and paid for his seat there. Before that he had his seat in another synagogue, close to where he and grandmother used to live. The most expensive seats were called mizrach 1, they resembled box seats in a theater.

My mother dressed up when she went to the synagogue. She didn't wear a wig because they were very expensive, and she couldn't afford such extravagancies. She wore a scarf on her head. When I turned 12 years old, I had a bat mitzvah in the synagogue, and after that my mother took me with her to the synagogue. Later, when my oldest brother married, his wife Genya started coming with us. My brothers attended the synagogue with our father every Saturday.

Grandpa Solomon was very religious. He prayed constantly. We had a large number of religious books including the Bible, the Talmud and prayer books in Yiddish and Hebrew, and my grandfather read all day long. Since the synagogue was so close to our house, he went there twice a day. The remaining time he would put on his tallit and tefillin and prayed at home. He taught me prayers. When he was in the synagogue, my mother would often send me there to bring him home. By then he was very old and had trouble walking. He was hunched; his beard and hair were white. He dressed in a long, black frock-coat, and his head was always covered with a yarmulka. My grandfather commanded a great deal of respect from the members of our family, and we all tried to be of help to him.

My mother always lit candles on Friday nights. Sabbath was observed according to the Jewish tradition: she made gefilte fish and chicken broth. Lunch was at 1 o'clock, and everyone gathered at the table. My grandfather said the prayer, and then we all had dinner and rested until the end of the day. We didn't clean the table until late in the evening. On Saturdays we weren't allowed to light a fire. Our Romanian neighbor, Milian, would stop by and put on the samovar. Once my father went into the yard and blew on the coal in the samovar. My grandfather kept admonishing him long afterwards saying, 'You think I didn't see through the window how you were blowing into the samovar?'

We observed Jewish holidays according to every rule. On Purim my mother baked hamantashen, and she also prepared chicken broth with dumplings. I cannot recall its Hebrew name. My grandfather read a prayer. In the evening musicians came and played Jewish melodies, and later my mother would give them money and feed them. I don't remember any Purimshpil, I only remember the meals at our house. While my grandfather was alive the meals were a lot more fun. On Chanukkah candles were lit by our father. We had a beautiful chanukkiyah, my mother's dowry. The poor who didn't own a chanukkiyah would cut a hole in the middle of a potato, fill it with oil and light a wick. These weren't candleholders but small lanterns. On Chanukkah my grandfather always gave me and my brothers 100 lei each. This wasn't just pocket money. When I started working, it took me a month to earn 100 lei!

On the eve of Pesach grandfather wouldn't leave my mother alone. He followed her around and scrutinized everything. Only when everything in the house was spotless and shiny, when all the bread crumbs and ends were swept and burned, when all the walls were whitewashed, only then did he allow himself to calm down. For Pesach we bought two poods [32 kg] of matzah. There were special bakeries that made it. We had matzah delivered in a giant canvass sack. Two poods of matzah is a lot. When the matzah was delivered, my mother would lay out a white sheet. The sack got turned inside out and the matzah remained on the sheet. I remember that the sheet hung in the bedroom. A tin sheet lay on the stove in the kitchen. We used to put matzah on it, and it was always crispy and warm. No bread was consumed during Pesach, God forbid!

Mother was in the kitchen all day long. She had beautiful Pesach china which was never used on other occasions. We heated goose fat and made cracklings. We roasted potatoes with cracklings, made different balls from potato and matzah, gefilte fish and chicken broth. Every day mother baked two cakes using matzah flower. Those cakes were called leiker and one was regular, the other one with nuts. We had visitors each day of Pesach, and a lot of food had to prepared. Of course I always helped. During Pesach, the kitchen was very animated and fun. I crushed matzah in a large mortar and made flour. Then it was sifted. My mother would mix fine flour for cakes and whatever remained in the sieve with eggs and make dumplings for chicken broth. Mother also baked delicious Pesach cookies.

For Simchat Torah all children were bought a 'fon' [Yiddish], a little flag. Its rod speared a little red apple with a candle inside, which was lit. And all the kids went to the synagogue with these 'fons' . We celebrated Sukkot, and my grandfather made a big sukkah in the yard. We, children, lived in it for a whole week. We also celebrated Rosh Hashanah with candles, a festive dinner, apples with honey and presents.

On Yom Kippur fasting was always observed. I fasted for the first time when I was 11. Ever since then I have been fasting on Yom Kippur.

When I turned 8 I began to go to school. There were two Hebrew schools in Kishinev but they were unable to take on all applicants. For this reason I attended a Romanian elementary school in my first year. My older brothers were taught in a Romanian school as well also because of the great number of students.

Every subject was taught in Romanian. We spoke Romanian, so it was no problem for us. The students were predominantly Jewish. There were Russians and Romanians, too, but there were more Jews. Elementary school was free; tuition fees were only required for gymnasium. The teachers were also Jewish, Romanian and Russian. There was no ethnic tension between the students or between students and teachers. There were separate schools for boys and girls.

My parents bought their own living quarters with my grandfather's help in 1932. It was a four-bedroom apartment, or rather the same kind of separate small house in a large courtyard we had before. My grandfather was always trying to convince my mother that it would be better to buy your own place and not pay rent when you're old. He had money which he received from the sale of his home after my grandmother died. Also, Uncle Khaim regularly sent money to him. Just like in the old place, there was a large courtyard with several houses that were referred to and numbered like apartments. The owner was a Jew and rented out these apartments to Jews only. We were the only tenants who bought an apartment from him. All the others just rented them.

I had a longer walk to school after we moved, and we had to switch synagogues and go to the one that was closer. My grandfather walked with difficulty. The new house only differed from our previous quarters by the number of rooms. The rest was all the same - the same kitchen, the same lack of running water and a sewer system, and the same furnace heating. Now my grandfather had his own room and so did our parents. I and my brother Ruvim also had our separate rooms. Ruvim finished school and went to work as an entry level worker for the construction company where my father worked. It's a shame that my grandfather could only enjoy his new home for one year. He died in 1933.

My oldest brother, Khuna, worked at a leather goods factory. He started working when he turned 11. He became a qualified specialist and earned good money. The owner of the factory was a Jew and only hired Jews. My brother had a fiancé, who was also a Jew. Her name was Genya Khais. Later we called her Zhenya. They were dating for six years: for two years before my brother went into the army and two years during his service in the Romanian army. A year after his return from the army my brother got officially engaged, and a year after that they got married. My brother said that he wouldn't get married until he could provide for his family on his own. He rented an apartment and bought furniture. After that, in 1935, they had their wedding.

The wedding was a traditional Jewish wedding. The celebrations weren't what they are now - in a restaurant until midnight - they lasted until morning back then. There were special wedding halls or people booked a large tavern. There were poorer weddings and richer weddings, and the number of guests depended on the size of the family. Since my father had five married sisters, they, along with their husbands and children and grandchildren, were invited, as well as my father's and my brother's co-workers. It was a large wedding with close to a hundred people. A chuppah was erected in the hall. The fathers of the bride and the groom led the groom to the chuppah. A rabbi said a prayer and the bride and the groom exchanged rings. They were given a shot of vodka and a piece of cake and the ceremony was complete.

Food for the wedding was prepared by women, who were especially invited and referred to as sarvern [Yiddish for 'cook']. They prepared Jewish dishes like gefilte fish, chicken, and sweet and sour stew. The stew was always served with maina, a pie that is prepared in the same way as strudel and made from the same dough, but the filling is minced meat mixed with home-made noodles and fried onions. The dough was most delicate and very difficult to roll. Maina and strudels were prepared by a highly skilled cook who didn't prepare any other food. The guests were served vodka and cake immediately after the ceremony, and afterwards everyone sat down. The tables were already catered with gefilte fish, which was always served with horseradish. After the fish, chicken broth, maina, boiled chicken and stew were served. Vodka and wine completed the meal. Later everyone danced. Klezmer musicians were invited and played all night long, so the dancing continued all night long. It started with the traditional sher, danced by everyone, the young and the old. Sher is danced in pairs; man and woman dance together. It can last for two hours. After that the klezmer musicians played Jewish and Moldovan music, tangos and waltzes. We danced all night. And then sweets were served. Weddings were always held on Sundays, and Saturdays before a wedding were called freilekher Shabbat, or happy Saturday. Guests visited the groom and bride with wedding gifts. Giving money wasn't customary. Gifts were things that the newly-weds would need to start their own home such as dishes, cutlery, household items, bed-linens and so on.

At the age of 7 I became a member of the Romanian Zionist youth sports organization, Maccabi. We had gymnastics, social interaction and attended lectures on Jewish history, traditions and culture. The club also organized events. On Saturdays we had dances and concerts. There were different groups: choir singing, athletics, dancing. The orchestra was superb. Once a year we were taken on a trip and lived in a summer camp by the river for two weeks. We had to wear a Maccabi uniform. The junior group girls wore a blue skirt, white shirt and white tennis shoes. On the left breast we had the Maccabi pin, and we wore a blue tie. At 14 I was moved to a senior group. The uniform differed slightly - the skirt was not blue but white.

This wasn't the only Zionist youth organization in Romania. There were also the Koikh, the Betar 3 and the Shomer [Hashomer Hatzair]. But none of these clubs had sports or music groups, they only pursued the Zionist agenda.

Every year on 10th May Romania marked the birthday of the Russian tsar with a celebration. [Editor's note: In realty 10th May commemorated the crowning of the first Romanian king and the creation of the Romanian Kingdom, which took place on 10th May 1883.] On that day there was always a parade. The Maccabi girls marched in the parade with their own orchestra. The entire town came to watch us. Perhaps it only seemed so to me, but we marched beautifully, and our orchestra was exceptional.

When I was 12, I finished a 4-year school, the 'primar'['elementary school' in Romanian]. There was no money for me to attend a gymnasium, so I went to work at a leather goods factory. The factory employed close to a hundred people and was considered a large factory. We made bags, belts and suitcases. Moldova didn't have heavy manufacturing plants but mostly private companies. My brother and I worked together. We were organized in teams of 6 or 7 at work, and every member of the team had his own task. I was very happy with my job. I began as an apprentice to a seamstress, cutting thread into equal pieces. Eventually I was promoted to senior trainee and then became an assistant. I was paid 100 lei a month. Of course it was difficult to survive on that little money, but it offered considerable help to my family.

Moldova wasn't under Soviet power but it had a Communist Party. The majority of communists were Jews. It was an underground party. They were forbidden to hold meetings and demonstrate with red flags. The police tried to arrest all communist before 1st May but the ones who remained demonstrated every year on 1st May, and in the end every one of them was arrested. Romanians disliked Jews because almost all the Jews were communist. Neither my father nor my brothers were communists but in their hearts, I think, they were sympathizers.

Young Moldovan Jews were allowed to leave for Palestine. Zionist youth organizations ran a program called hakhsharah. This was a blessing for children of poor families who wanted to leave but couldn't afford the fare. They had to do six months of hard work at state organizations. They weren't paid, but they were fed and had a place to live. After that they were issued certificates of passage and left for Israel. The last migration was in 1936, and my Maccabi girlfriends left. The Soviet authorities detained this steamship and kept it anchored at sea for three months. There was death, illness, famine and frost. Three months later they reached Palestine, but many people had died during the journey. After her arrival in Palestine, my friend Sarrah Arshirovich wrote to me and sent a photograph. There was work there, provided you could and wanted to work. They built kibbutzim. What the first settlers did was absolutely fantastic. They said they couldn't imagine how to build a country on that foundation - rock, clay and sand - but what a country they managed to build! They turned it into heaven on earth, one big garden of Eden. I have always dreamt of seeing Israel before I die, but I don't think it will happen. It's expensive to go there now, plus my age is an obstacle. God willing, let there be peace and harmony.

In 1933 Hitler came to power in Germany. We heard vague rumors about Jews being victimized in Germany. But that was far away, and we had our own life here. After Hitler's attack on Poland and the death of my mother's brother Zeilik and his family, the horrors of fascism became more real. But I could never imagine that I would have to flee from my house one day and survive a war. I think my parents had more of an idea about it. Mother used to say, 'Who knows what this Hitler may do. The living may yet envy the dead'.

I remember the arrival of the Soviet power in Moldova. In the evening of 26th June 1940, I was visiting with my girlfriend. Her mother came home and said, 'Did you hear what they broadcast on the radio? Stalin announced that unless they give us Bessarabia 3 back, we will go to war'. Only one household on our street had a radio. I went home and repeated what I had heard. All the neighbors came to listen; they were all alarmed. By the next morning there were no Romanians left in Kishinev. They left everything behind and fled. Some left by train, some by car, others on horse and carriage. The Romanians were crying as they were leaving, but they couldn't stay. They knew that they wouldn't survive under the Soviet power. They wanted to be free. Between 27th and 30th June everyone was free to leave, not only the Romanians. It was mainly the Jews who came here [to Ukraine]. They thought that the Soviet power would relieve them from poverty and anti- Semitism. For some reason they believed in ideas of the revolution and in egalitarianism. This happened on Friday. Mother was still preparing for Sabbath, as always, and while washing dishes she said to me, 'We are living without any authority. The old one is on the way out and the new one has yet to come.'

At five o'clock in the morning on 28th June the first Soviet airplane landed. Soviet communists used it to distribute flyers. I remember the following words, 'Comrades, we shall free you from the fetters of the rich and of the boyars'. Local communists printed similar flyers. They went from door to door and left a flyer under each one. By morning tanks roared on paved roads. My mother sat in the yard. Our gate was facing the square. The tanks stopped by the water pump. Soldiers crawled out from the tanks, washed themselves and went to the city center. They didn't take their tanks or trucks. They left all their equipment and went to town on foot. They returned with bags. For the main part they bought shoes, carrying 5 to 10 boxes of shoes. Mother kept asking, 'Don't they have shoes there?' In those days we couldn't imagine that shops may not stock shoes, that Soviet stores had absolutely nothing! This way they emptied our stores from all the merchandise in one week. Then there was a military parade. The tanks were leading the parade, followed by cars, and then we, the workers, followed on foot. We welcomed the Soviets wholeheartedly. Although the rich, the businessmen and the shopkeepers weren't too keen on the new regime.

In the beginning we couldn't accustom to the new way of living. And then we suddenly had everything under the sun, and it could all be bought for next to nothing. I earned 600 rubles a month, and the best roll was only 30 kopeks and a bagel was 30 kopeks, too. Everything was cheap, and shops were brimming with goods. Politics never entered my mind. At that time I had other interests. We would gather at my house or at my girlfriends'. Every evening we either strolled on the boulevard or went to the cinema, or sang and danced in a group. Back then most of my friends were Jewish because I met them either at the factory, which only employed Jews, or at the Maccabi. We didn't concern ourselves with the change of power. My mother knew Russian, and I started picking it up, too. So when the Russians came I could communicate with them.

My parents had shown signs of illness at that time already. My father suffered from hypertension, and my mother was diagnosed with inoperable cancer. Once, speaking of something else, she said, 'When I die...', and my father replied, 'No, I will die first'. And I remember him saying after that, 'Let's die together'. And that's what happened: my mother died on 29th May 1941, three weeks before the beginning of the war. My father only outlived her by 10 months.

On 22nd June 1941 we heard thunder. It was light outside and a beautiful day. In June it's already light at 5am. The sky was blue and it was unclear where the storm was coming from. As a joke I said, 'War must have started'. When we got up, we heard an air-raid warning. When the bomber planes appeared and began bombing we hid in the basement of the synagogue. People sought shelter there from all the adjoining streets.

My older brother, Khuna, was mobilized on 26th June 1941. He was lucky: he was drafted on 15th July when everyone left because the city was on fire. He returned. Later all Kishinev residents volunteered for the front but they were all dismissed. They were regarded as unreliable and weren't trusted to go to the front. In early August my father, Ruvim and I were evacuated. At first we stayed in Kramatorsk where we worked for a month, but the Germans were approaching, and we had to move on. We traveled on open rail cars. Among other cars there were the ones filled with sand. The wind blew sand on us, and then it began to rain. Then we saw these three 'birdies', as we used to refer to airplanes. Our airplanes flew like those did; two at the front, one in the back. The Germans imitated this formation. When they came close we recognized by the sound that those weren't our planes. It was frightening. We forgot about the sand and the rain.

The train kept on moving. We were shelled. They destroyed a few cars, but ours was spared. We reached a station where two cars with soldiers had been blown up. One guy in a soldier's uniform stood there. He was shaking and afraid to board the train. He looked as if he were dead. He told us that the ones that survived had dug huge ditches and dumped all the dead bodies into them. At this train stop we were assigned to work at a large factory. We worked there for two months, but the front was getting closer and again we were on the move.

A few days we walked on foot as trains didn't stop at the station in Kramatorsk. Once there was a huge rainstorm, and we stopped to sleep at some local club. It turned out that this settlement was a German colony. In the morning we went to the village to buy food. These Germans lived in poverty, but everything was spotlessly clean. They had cotton dresses, blouses, head-scarves - all impeccably clean and ironed. We entered a house, and there was a woman in her summer kitchen, and she was making mamaliga. We asked her to sell us some food. She made us mamaliga, gave us lard to go with it and milk. We ate there and whatever mamaliga was left she let us take with us. We wanted to pay her but she refused to take any money. She said that this was the very least she could do for us to try and alleviate Germany's guilt. Eventually we ended up in Essentuki in the Caucasus. We stayed there a few months, working the fields, harvesting. Right there, in the field, the kolkhoz cook made food for us on the bonfire by using some grain and corn. We picked fruit and were allowed to eat whatever we liked. We recollected our strength there a little before we moved ahead.

The local population hoped that Hitler would liberate them from the Soviet power. Each day they expected him to come in a month or two. One morning we got up, got ready and walked 15 kilometers to Essentuki. There were trains running from there. From Krasnodar we were all going to Tashkent. We squeezed into a train car and continued moving ahead. We reached Georgievsk station, which is still in the Caucasus. This was a German colony. All local residents were deported there. Everything remained untouched, as it was when the owners were still there. There were cows, pigs, chickens and so on. We were told to move into empty houses and live there as if they were our own. These houses were very lowly, but everything was clean. None of us stayed because Georgievsk was a dead end. The road literally ended there. If Germans had come there we wouldn't have been able to escape. We kept moving. We reached Makhachkala, but it was full of evacuees. We remained there for three days. Leaving there was fraught with difficulty because the trains were packed. My brother got himself hired as a stevedore on a steamboat. In exchange he was given three tickets, and we traveled on this ship. We sailed for three days. The moon was luminous against the velvet sky, but we were hungry and all our thoughts were concentrated on food. We arrived in Krasnovodsk. There was even more hunger there. There were thousands of people. It was impossible to get a piece of bread. From there we took a train to Tashkent.

In Tashkent we met our sister-in-law, Khuna's wife, who was pregnant, at the end of her last trimester. Again we were put onto a train. Each day we were informed that the train was now passing Samarkand, Namangan, Fergana and so on. We stopped at Ursatovskaya station in Tashkent region. We were directed to a Kaganovich 4 kolkhoz. It was winter already. When we got to the kolkhoz we were immediately given bread. There were orders to feed us. They made out well at our expense - sometimes they fed us, sometimes they didn't.

My father got a job as a construction worker. They didn't get fed at his workplace, and he was always hungry. He had no shoes. Frostbite was severe. He was hospitalized, and his leg was amputated. At the same time I was in hospital with typhoid fever. For ten days my temperature was 40 degrees, but I didn't receive a single injection and wasn't given a single pill. They said that all good doctors were at the front, and all medication was being sent there, too. We were each given a small piece of bread, which they put on our pillows. When I turned my head the bread was gone. Someone had taken it. I couldn't eat anyway. When I was discharged I weighed less than 40 kilos. In the hospital they shaved my head. I couldn't walk because I was too weak. I sat down on a bench in the hospital yard. A woman came out and asked why I was sitting there. I explained that I had just been released from the hospital and that the kolkhoz was 6 kilometers from here, and that I couldn't make it. This woman returned with a piece of bread but I couldn't eat due to extreme atrophy. At this time my brother came to get me. It was him who told me that our father was in the hospital and that his leg had been amputated. We went to the hospital to visit him. He was in the hallway because there was no space in the rooms. In the hallway I was given a chair next to someone's bed. I sat down. The man in the bed was my father but I didn't recognize him. On the side there was a mirror. When I looked into it, I didn't recognize myself either. And my father failed to recognize me, too. He was given some food. I tried to feed him but he refused to eat. I was given food too, I ate a little. Three days later, on 19th March 1942, my father died.

I returned to the kolkhoz. My brother left for Tashkent and got a job at a construction site. I was bedridden and unable to walk. There was no food. The woman I shared the room with went to see the secretary of the party committee and told him about my condition. He brought me bread himself, but I couldn't eat. After that his wife came and brought me a cup of soup. She fed me one spoonful. I will remember that spoonful until the day I die. And thus, little by little, I began eating some soup. The next day I was able to swallow a little bit of bread. We were sent to harvest wheat. We were allotted 5 kilograms of flour every 10 days. Once we were in the field when lunch was being prepared for kolkhoz workers. It was broth with a piece of lamb. When the chairman of the kolkhoz spotted us, he gave orders to feed us, too. We were given bread and a little bit of broth with lamb. This soup with the piece of meat got me back on my feet.

We lived in tents, on an earthen floor. I shared my tent with a woman and her daughter, who were also from Kishinev. We lived as one family. In the summer we started saving pieces of saxaul bush to have something to heat our place with in the winter. Flour was handed out regularly. I put a little bit aside each time and when I amassed a small bag, I traded it for a skirt. Until then I walked around in a skirt made from a tattered hospital sheet, which a nurse had given me as a present.

A few months later my brother returned to bring me to Tashkent, to work at a construction site. I was a pump operator there. When we were digging a foundation pit, underground water would rise. It needed to be removed from the pit with a pump. It was my responsibility to turn the pump on with a switch-knife. Two months after I arrived my brother was mobilized and sent to the front.

I lived in a dormitory. The construction company had good dormitories. There were 12 people of different nationalities in our room. We had a Moldovan woman, two Estonians, one Pole, one Russian woman from Belarus, and Riva from Moscow. We were young and after work the Estonians sang in Estonian and danced, the Moldovan woman sang in Moldovan along with me, and the Polish woman sang in Polish. We had no conflicts of nationality in the dormitory. Quite the opposite; everyone tried to help each other. I recovered a bit there. After all, we were fed three times a day - breakfast, lunch and dinner plus 800 grams of bread. I could sell half a kilo in return for food vouchers. The salary was low, and I needed to save a few hundred rubles in order to buy winter boots. I ended up buying a patched-up pair for 350 rubles. This required that I sold half a kilo of bread every day. The rest I ate.

When the construction was completed I went to a different site, which was also in Tashkent. They distributed overalls there. I worked as an operator again. They fed us even better, and we lived happily together in the dormitories. I worked there until the end of the war.

When I worked in Tashkent I visited my sister-in-law, Zhenya, my oldest brother's wife. In Tashkent she gave birth to a son, who was named Monya Solomon in honor of her grandfather. When the boy was three years old Zhenya died. The child was put into an orphanage. In February 1945 my oldest brother, Khuna, found me. He was in Alma-Ata. He had been wounded four times. Three times he returned to the front. After the fourth time he was sent to a hospital in Alma-Ata. This is where we found him at the end of the war, and that's where he remained. He went to work for a leather goods factory and married again. His Jewish wife was named Tzilya. When my brother learned that his son was in an orphanage he asked me to take Monya from there and bring him to him. I brought his son to Alma-Ata. He had two girls, Lusya and Yana, with his second wife. Khuna died in 1974, almost immediately after his retirement.

My brother Ruvim, who was drafted into the army in Tashkent, never went to the front. He told the military committee that he was a builder and was sent to rebuild the city of Gorky. He worked for a military factory until the end of the war. After the war he settled in Chernovtsy and continued working in construction. He married and had a son named Yankel. Ruvim died in 1980.

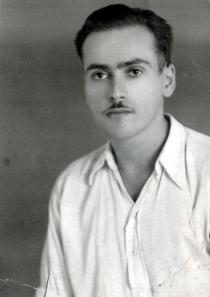

It was in Tashkent, at the construction site, that I met my future husband, Iosif Schwartzman, a Jew. We worked together. He was born in 1914 in Yedinsty, Moldova. Iosif completed a Hebrew school in Yedintsy. He came from a religious family, knew Yiddish and read prayers. He courted me for a long time.

Before the war I fell in love with a guy, whom I had met at Maccabi. He was drafted into the army. No one thought there would be a war. He asked whether I would wait until he returned. I had no news of him during the war. I waited for him during the war and thought that if he returned from the front without arms or legs, I still wouldn't refuse him. Afterwards, after the victory, I received a letter from his brother, in which he told me that Izya was killed on 17th April 1945. On 9th May the war was declared over. My entire life I only loved Izya. My marriage to Iosif wasn't a marriage of love, it was an escape from loneliness.

I took my brother's son to him and stayed in Alma-Ata. Iosif joined me there and we got married. There was no wedding, we simply registered with a marriage bureau. We lived in Alma-Ata for a year and then decided to return home. The town of Yedintsy was almost entirely destroyed. My building in Kishinev was still standing, but in order to move in I had to prove through the courts that I had lived there before the war. Neighbors offered to give evidence to that effect but demanded money in return. We didn't have any and agreed to go to Chernovtsy. During evacuation I befriended a woman from Chernovtsy who had great things to say about this city. We arrived in Chernovtsy in 1946. The city hadn't been damaged during the war, and there were plenty of vacant apartments because local residents fled Romania after the invasion of Soviet troops in 1940. We were allocated an apartment in which I still live today.

Our daughter was born on 24th January 1947. We named her Charna. She gave my life a purpose. 1947 was the year of a terrible famine. I didn't enroll my daughter in a nursery because children were starving there. Of course we were starving as well. I had little milk, and she had to be put on formula early on. She ate hot serial and potatoes without butter but grew up a healthy, good child. I stayed at home with Charna until she turned 5. We had no one to help us, neither I nor my husband had parents any more. Charna never knew what grandparents are. I signed her up in a kindergarten and went to work for the Chernovtsy leather goods factory. I was hired as a lab assistant in a testing plant where new models of handbags were developed. My husband worked at the rubber shoe factory. We lived modestly.

I tried to observe Jewish traditions, which I have grown up with in my family. Even when money was extremely tight I used to put a little aside over the course of the year to have something for Pesach. We bought matzah, and I prepared the Pesach dishes that I loved as a child. When I was setting up my home I made sure that we had Pesach china. My husband was a lot more neutral in this regard. On Pesach and Yom Kippur he went to the synagogue, but he refused to fast on Yom Kippur. On Chanukkah I always gave my daughter money.

Chernovtsy was a Jewish town. There were five or six synagogues and a Jewish community. I only went to the synagogue on Pesach because it wasn't free and there was always a shortage of money. I celebrated Sabbath, too. I remember my mother saying that Sabbath must not be disregarded by inattentiveness. I lit candles and tried to prepare some treats, make gefilte fish and boil a chicken. I didn't adhere to the law that forbade to work on Saturdays though. Back then Saturday was part of the official work week, and we were obliged to go to work. All household chores were left for Sundays. I didn't celebrate Soviet holidays, perhaps because I didn't have a chance to get accustomed to them in my childhood. What brought me joy was that Soviet holidays were always a day off. I didn't perceive any anti-Semitism in Chernovtsy. Most people I worked with were Jews as were my husband's and my friends.

Personally, I didn't experience the campaign against cosmopolitans 5, which began in 1948. I was an insignificant person to them, and this oppression didn't reach out to people like me. It was noticeable in Chernovtsy by the closure of synagogues, leaving only one, the smallest one, open. The largest synagogue was converted into a storage space for metal. The Hebrew middle school was shut down, and the Jewish musical theater was closed. My husband and I had often gone there before; we used to attend every new show.

We were very much affected by the Doctors' Plot 6. There was an outburst of anti-Semitism. I remember a boy who approached me on the street and said, 'Soon you will go to Siberia'. But the brunt of all hostility was endured by the doctors. The best medical scholars were called killers and fired from work.

During the Doctors' Plot my daughter, who was in the 1st grade at the time, found out that she was Jewish. She came home from school and said to us, 'You know, Jews are no good, they killed Stalin. Our teacher said that'. All the children in the courtyard began inquiring into who was Jewish and who wasn't and refused to play with Jewish kids. I overheard my daughter saying to her girlfriend that she wasn't Jewish. My heart stopped beating for a second. That evening we had a long discussion with my daughter about being Jewish, and I tried to explain to her that those who call Jews killers are malicious and foolish people. We had quite a few of these talks. I noticed, nonetheless, that ever since then Charna closed up. It was unpleasant for her that I celebrated Jewish holidays and spoke Yiddish with my husband. We spoke Russian with her.

In those days there was persistent talk of the deportation of all Jews to Siberia. People stocked up on canned food and grains. Bags with food for the road were standing ready in almost every home. We believed in these rumors because we all remembered the deportation of Jews from the Crimea. Fortunately, because of Stalin's death in 1953, this never happened.

I remember Stalin's death in March 1953. People on the streets wore red and black mourning armbands. Their faces were puffy from tears. Yes, it's true, during Stalin's last years there was state anti- Semitism, but I believe that Stalin cannot be blamed for that. He actually liked Jews. He helped Jews a lot during the war. He said: 'The evacuated must be fed, the evacuated mustn't be harmed'. I think that the Doctors' Plot was a provocation premeditated by his enemies. If these doctors had still enjoyed their freedom, it would have been possible for Stalin to survive, that they would have saved him. This was all masterminded by those, who tried to take his place. After all, anti-Semitism didn't cease after Stalin's death, which suggests that someone wanted to keep it that way. Of course, I grieved when Stalin died. I was petrified by the thought of what would come after him. When Stalin was publicly denounced as enemy of the state at the Twentieth Party Congress 7, I believed it. Still I think that Stalin was deliberately misled regarding the guilt of those accused of being enemies of the state. After all, he couldn't possibly oversee everything. He had to trust his advisors but they pursued their own agenda. And then Stalin alone was blamed for it all.

When Charna turned 8 she was enrolled in a Russian school. She had no Jewish friends at school and at university. She graduated from school in 1965 and started working as a teacher in a kindergarten while studying by correspondence in the English Department of the Romano- Germanic College at Kiev University. She graduated from university in 1971.

I retired in 1979, and that same year my daughter got married. I don't know how and where she met her future husband, Nikolai Galkin. He was Russian and lived in Moscow. Charna moved there. Once a year she visited Chernovtsy. In Moscow she worked as a kindergarten teacher. She loved kids but didn't have any of her own. To my questions regarding her marriage, Charna's reply was always that everything was fine. Much later I found out from her girlfriend that her husband constantly beat her, and screamed that his Jewish wife had ruined his life. Unfortunately I only found this out after her death. She died from a heart attack in 2001. After her funeral and cremation in Moscow I took her ashes and buried them in the Jewish section of the cemetery in Chernovtsy. Hesed erected a tombstone on her grave. Next to Charna's name there is room for mine on this tombstone. There I will lie, beside my little girl, when it's my time.

My husband and I were overjoyed to learn about the creation of the state of Israel. I knew how much effort was invested in this country, and it pleased me to learn that I had my own country, that our Galut [wandering] was over. When the Jewish immigration to Israel began in the 1970s, I sympathized with those leaving, but I didn't go myself. My husband died in 1969. I buried him in the Jewish cemetery, according to Jewish tradition. I couldn't leave my daughter, and she didn't wish to leave with me. I was offended not by those who were leaving, but by those who failed to assimilate in Israel for some reason, those who returned and began to drag Israel through the mud publicly, through newspapers and television, telling tales of how Zionists lured them there with lies and how unbearable it was for a Soviet person to live there. There were such people in Chernovtsy as well. It was an offense to hear them speak like that.

The live of Jews has drastically changed over the last 10 years. Synagogues started to open again as well as Hebrew schools. I don't feel any anti-Semitism. As to me, I treat people as they deserve to be treated, not according to their nationality. For example, I have lived with my neighbors for 47 years. They are a Russian family, but I honestly cannot say whether I would have lived in such harmony with a Jewish family. These good neighbors are somehow my family, too. We don't pause to think about which one of us is good and which one isn't. Since we are all friends, we are all good people. They have been a great help to me, especially after my daughter's death.

We have Hesed in Chernovtsy and various other Jewish organizations. I began attending lectures and concerts. I met many new friends in the Jewish community. We observe Sabbath and celebrate Jewish holidays. Hesed also helps us with food and medicine. They organize daily lunches for the needy. After my daughter died, I withdrew from participation in community affairs; I simply had other things on my mind. I don't go anywhere these days, except for the cemetery and the market. My friends supported me in my grief. Hesed volunteers visit me almost daily. They spend an hour or two with me and make me feel that I'm not alone. These days that's more important than material or financial help. We talk, read Hebrew books out loud, and my sense of loneliness abates a little. Time will pass, and I will probably return to my friends in the Jewish community. For now, I am grateful to them for everything.

Glossary