Isaac Rozenfain

Kishinev

Moldova

Interviewer: Nathalia Fomina

Date of interview: September, November 2004

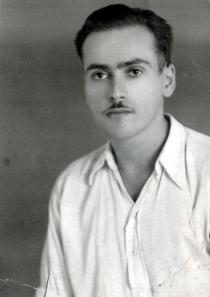

Isaac Rozenfain is a lean man of medium height with fine features. He has a moustache and combs his hair back, giving way to his large forehead. He wears glasses with obscure glass. When talking he looks at you intently, but at times he seems to drift off into his own world, recalling something deeply personal, and is in no hurry to share what is on his mind. Isaac and I had a meeting at the Jewish municipal library. Isaac is a very nice, intelligent man with impeccable manners and a sense of dignity. However, he is rather taciturn and reserved: there are subjects he never discusses, subjects that he determined for himself based on his sad experiences in life. Therefore, he often used phrases such as 'I don't know' or 'I don't remember', particularly when it came to politics.

My family background

Growing up

During the War

Post-war

Glossary

Unfortunately, I know nothing about my father's parents. I didn't know them and never saw photographs of them either. All I know is that my paternal grandfather's name was Moisey Rozenfain and he lived in Nevel [a district town in Vitebsk province, 980 km from Kishinev]. We lived in Bessarabia 1, and Nevel belonged to the USSR [during the Soviet regime Nevel was in Pskov region, today Russia]"and my father's relatives never traveled to Kishinev. My father may have spoken about his parents, when I was small, but I can't remember anything. I have no doubts that my grandfather and grandmother were religious since my father was given a traditional Jewish education. I don't know how many sisters or brothers my father had. I met only one of his brothers, who visited us in Nevel after the Great Patriotic War 2. I have a photo taken on this occasion, but unfortunately I cannot remember my uncle's name.

My father, Wolf Rozenfain, was born in Nevel in 1888. He must have had education in addition to cheder since he knew Hebrew. They didn't learn Hebrew properly in cheder, and my father knew Hebrew to such an extent, that he simply couldn't just have learned it in cheder. He also spoke fluent Russian. My father must have moved to Kishinev before 1918, before Bessarabia was annexed to Romania [see Annexation of Bessarabia to Romania] 3. I don't know what my father was doing then. My parents met in Kishinev, but I don't know any details in this regard. My parents got married in 1920.

My maternal grandfather, Israel Kesselman, came from some place near Kiev. I don't know my grandmother's name. My grandfather and grandmother died before I was born. I know that they had to leave their hometown near Kiev due to the resettlement of Jews within the [Jewish] Pale of Settlement 4. The family moved to the village of Eskipolos [today Glubokoye, Ukraine] near Tatarbunar in Bessarabia province [650 km from Kiev].

I remember that my mother's sister Mania Shusterman [nee Kesselman] lived in Eskipolos. Aunt Mania was the oldest of the siblings. She was a housewife. I don't remember her husband. Her son Abram, my cousin brother, was about 20 years older than me and always patronized me. Abram was a Revisionist Zionist [see Revisionist Zionism] 5, and a rather adamant one. He was one of the leaders of Betar 6 in Bessarabia, on an official basis: he was paid for his work; he was an employee of Betar. He was an engineer by vocation. He passed his tests extramurally in Paris. Abram had a hearing problem, which was the result of lightning that struck their house in Eskipolos in his childhood. It killed Abram's sister, whose name I can't remember. She had two children: Izia and Nelia, my nephew and niece.

Mama also had two brothers, whose names I don't remember. One of them lived in Galaz in Romania. He died before World War II. The second brother moved to South America at the beginning of the century. He lived in Buenos Aires. I remember that my parents corresponded with him. My uncle had a big family: a son, Izia, named after grandfather Israel Kesselman, and three daughters: Sarita, Dorita and Berthidalia, in the local manner. Their Jewish names were Sarah, Dora and Bertha. I never met them, but I remember their rather unusual names. My uncle must have been a wealthy man. I was supposed to move to America to continue my education after finishing the technical school. Later, my family decided I should continue my education in Civitavecchia near Rome [Italy] and my uncle was to pay for it. My uncle died after the war, in the late 1950s, early 1960s. I didn't correspond with my cousins. [The interviewee is referring to the fact that it was dangerous to keep in touch with relatives abroad] 7.

My mother, Fania Rozenfain, nee Kesselman, was born near Kiev in 1890. She lived in Tatarbunari before she moved to Kishinev. She must have finished a school of 'assistant doctors' there. [Editor's note: In Russian the term 'assistant doctor' (from the German 'Feldscher') is the equivalent of medical nurse. As a rule men were feldschers and women were nurses.] Mama got married at the age of almost 30, and I guess hers was a prearranged marriage.

After the wedding my parents settled down in a one-storied house with a verandah on Alexandrovskaya Street [today Stefan cel Mare Street] in Kishinev, where I was born on 28th October 1921. I remember this house very well. My mother showed it to me when I grew older. Later we moved to 29, Kupecheskaya Street [today Negruzzi Street]. We always rented two-bedroom apartments, but I don't remember the details of this apartment. From Kupecheskaya we moved to Mikhailovskaya on the corner of Sadovaya Street.

My father was the director of the Jewish elementary school of the Society of Sale Clerks for Cooperation [founded in 1886] on Irinopolskaya Street. He taught Hebrew and mathematics at school. My father was short and wore glasses. When he returned home from work he enjoyed reading Jewish and Russian newspapers. My father subscribed to the Jewish paper 'Undzere Zeit' [Yiddish for 'Our Time']. We had a collection of books in Hebrew and Russian at home. However, the books in Hebrew were philosophical works and fiction rather than religious ones. We spoke Russian at home. Mama and Papa occasionally spoke Yiddish, but my mother's Yiddish was much poorer than my father's. Mama worked as an assistant doctor in a private clinic. She knew no Romanian and for this reason couldn't find a job in a state-run clinic. Mama was tall and stately. She had thick, long hair that she wore in plaits crowning her head. Mama's friend Manechka, a Jewish woman and a morphine- addict, who also worked in this clinic, had an affair with the chief doctor. For some reason I remember this, though I was just six or seven years old then. We occasionally had guests, but I don't remember any other of my parents' friends.

We always had meals together at the same time. Papa sat at the head of the table. Mama laid the table. She cooked gefilte fish, chicken broth with home-made noodles, and potato pancakes [latkes]. The food was delicious. Mama was really good at cooking. Our family wasn't extremely religious. I wouldn't say that we followed all rules at Sabbath, though Papa certainly didn't work on this day. Papa went to the synagogue on holidays, but he didn't have his own seat there. I went to the synagogue with him. We celebrated Jewish holidays. I remember Easter. [Editor's note: Mr. Rozenfain speaks Russian. In Russian the words 'Pesach' and 'Paskha' (Christian term) are very similar and Russian-speaking Jews often use 'Paskha' instead of 'Pesach'.] We had special fancy crockery. Papa conducted the seder according to the rules. He reclined on cushions at the head of the table. There was no bread in the house during the holiday [mitzvah of biur chametz]. When I was five or six years old I looked for the afikoman, but I don't remember any details. They say childhood events imprint on the memory, but that's not the case with me. We had Easter celebrations till the beginning of the war, but I don't remember myself during seder, when I was in my teens.

I must have been given some money on Chanukkah [the traditional Chanukkah gelt], but I don't remember. On Purim Mama made hamantashen and fluden with honey and nuts. I also remember how we took shelakhmones to our acquaintances on Purim [mishlo'ah manot, sending of gifts to one another]. We didn't make a sukkah [at Sukkot] and neither did any of our acquaintances, so I didn't see one in my childhood.

Most of my friends were Jews, but when we moved to Mikhailovskaya Street I met Shurka Kapevar, a Russian boy, who became my very close friend. His maternal grandfather was a priest. Shurka showed me records of Shaliapin [Shaliapin, Fyodor Ivanovich (1873-1938): famous Russian bass singer], with the singer's personal dedication to Shurka's mother. When I grew older I incidentally heard that she had had an affair with Shaliapin when she was young.

My parents and I often spent our summer vacations with Aunt Mania in Eskipolos on the Black Sea firth. We went by train to Arciz [180 km from Kishinev], which took a few hours, and from there we rode for some more hours on a horse-drawn wagon. There was a lovely beach there with fine yellow sand. I enjoyed lying in the sun. I learned to swim and used to swim far into the sea and sway lying on my back on the waves. I also enjoyed spending time with my cousin Abram, whom I loved dearly. He often traveled to Kishinev on Betar business.

I went to the Jewish school where my father was director. We studied most subjects in Romanian, but we also studied Hebrew and Jewish history in Hebrew. Regretfully, I don't remember any Hebrew. After successfully finishing elementary school, I entered the Aleku Russo boys' gymnasium [named after Russo, Aleku (1781-1859), Romanian writer and essayist]. This building on the corner of Pushkin and Pirogov Streets houses one of the university faculties now. This was the only gymnasium in Kishinev, which exercised the five percent quota 8 for Jewish students. [Editor's note: as the five percent quota existed in Russia before 1917 it is possible that it also existed in some schools in Romania.] However, my father decided I should only go there - that's how good it was. Our Jewish neighbors' son, who was about three years older than me, studied there and my parents decided I should try.

There were Romanian and Russian boys in my class, but only three Jewish boys: Kryuk, Balter and I. We had very good teachers. I remember Skodigora, our teacher of mathematics. His brother taught us natural sciences. Our Romanian teacher was Usatiuk, a member of the Iron Guard 9. There were fascists in Romania at that time. Usatiuk gave me a '9' - we had marks from 1 [worst] to 10 [best] - for the Romanian language in the 2nd or 3rd grade, and this was a high mark, and he hardly ever gave such a high mark to anybody else. This was quite a surprise for me.

Once I faced the hidden antipathy of my peers. I can still remember this very well. One day in spring we played 'oina,' a Romanian ball game. Two players standing in front of each other try to strike the third player running from one to the other with a ball. I stood with my back to a window of the gymnasium. The ball broke the window, but it was obviously not my doing considering that I was standing with my back to the window. Anyway, when the janitor came by, the other boys stated unanimously that I hade done it. Besides punishment, the one to blame was to pay for the broken window. I felt like crying. This actually showed they disliked Jews in my view. We weren't allowed to speak Russian in the gymnasium. [Editor's note: The reason for this was to introduce the Romanian language publicly as well as at higher educational institutions in the formerly Russian province.] Since we often spoke Russian at home I switched to it in the gymnasium. My classmate Dolumansi often threatened, 'I will show you how to speak Russian!' By the way, he was a Gagauz 10, I'd say.

I had moderate success at the gymnasium, but I was fond of sports like everybody else. I went to play ping-pong at the gym of the Jewish sports society Maccabi 11 on Harlampievskaya Street. I also played volley-ball for the team of our gymnasium. There were competitions between the town gymnasiums for boys. They were named after Romanian and Moldovan writers: Bogdan Hasdeu [Hasdeu, Bogdan Petreceicu (1838-1907): Romanian scholar, writer, historian and essayist], Alexandru Donici [Donici, Alexandru (1806- 1865): Moldovan writer, translator, the creator of the Moldovan national fable], Eminescu 12; by the way this latter gymnasium was called Jewish in the town, as many Jewish students studied there.

The Kishinev of my youth wasn't a very big town. It had a population of about 100,000 people. [According to the all-Russian census of 1897, Kishinev had 108,483 residents, 50,237 of who were Jews.] The only three- storied building was on Alexandrovskaya Street on the corner of Kupecheskaya Street: its owner was Barbalat, who also owned a big clothes store. There was a tram running along Armianskaya, Pushkin and Alexandrovskaya Streets. One of the brightest memories of this time I have is of two dead bodies on the corner of Alexandrovskaya and Pushkin Streets, guarded by a policeman. This happened in the late 1930s, when the Iron Guards killed the Prime Minister of Romania [Armand Calinescu, Premier of Romania, was murdered in September 1939.] King Carol II 13 ordered the carrying out of demonstrative executions of leaders of the Iron Guard in big towns in Romania. In our town the spot for this was across the street from the 'Children's World' store, and people passed this location hurriedly or preferred to avoid it at all.

I loved cinema and wanted to become a film director. I often went to the Orpheum on the corner of Alexandrovskaya and Pushkin Streets, the Coliseum on Podolskaya Street, and the Odeon cinema. I didn't want to miss a single movie. However, this was a problem. We weren't really wealthy and a ticket cost 16 Lei [the price of a tram ticket was 30 Ban (0,3 Leu)], which was rather sufficient for a gymnasium student. I remember movies with Gary Cooper, Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo. I particularly liked step dance and never missed one movie with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

The gymnasium students liked walking along Alexandrovskaya Street, the Broadway of our town. We walked from Gogol to Sinadinovskaya Street, on the right side of the railway station. We made acquaintances, walked and talked. This love of walking played an evil trick on me. One afternoon, when I was supposed to be in class, I was noticed by a gymnasium tutor, who was to watch over the students. I was walking with a girl and I was smoking a cigarette. I was 15 or 16 years. I was immediately expelled from the gymnasium, and my father's attempts to restore me there failed.

The family council decided that I should go to a technical school. I entered the construction technical school on the corner of Zhukovskaya and Lyovskaya Streets. My sad experience changed my attitude towards my studies and I became one of the best students in the technical school. This school was owned by a priest. Architect Merz, a German, was the best teacher. The recruitment age to the Romanian army was 20 and I didn't have to go to the army before 1940. I was born the same year as the son of Karl II, Mihay [King Michael] 14. This was supposed to release me from the army service, and also, I guess the month and the date had to coincide. I also remember the rumors that Mihay wounded his father's lover and that she was a Jew. The situation for Jews got much worse then. I remember the New Year [Christian] celebration when Antonescu 15 was the ruler. There was the threat of pogroms and the celebration was very quiet. I don't know how serious this threat really was, but the feeling of fear prevailed. I don't remember whether they introduced any anti-Jewish laws in Romania 16 at that time, but there was this kind of spirit in the air.

Perhaps for this reason we welcomed the Soviet forces, entering the town on 29th June 1940 [see Annexation of Bessarabia to the USSR] 17. People were waiting for them all night long. I stood on the corner of Armianskaya and Alexandrovskaya Streets. There were crowds of people around. At 4am the first tanks entered the town. The tank men stopped their tanks and came out hugging people. When the Soviet rule was established, teaching at the technical school continued, only the priest stopped being its owner. Our teachers stayed. They knew Russian very well and started teaching us in Russian. A few other boys and I repaired two rooms in a building to house the district Komsomol 18 committee. We plastered and whitewashed the walls. I joined the Komsomol sincerely and with all my heart. I liked the meetings, discussions and Subbotniks 19, when we planted trees.

Then wealthier people began to be deported from Kishinev. The parents of one of my mates were deported, but he was allowed to stay in the town and continue his studies. The Stalin principle of children not being responsible for their fathers was in force ['A son is not responsible for his father', I.V. Stalin, 1935]. Once, this student whose Russian was poor asked me to help him write a request to Stalin to release his parents. We were sitting in the classroom writing this letter, when the secretary of the Komsomol unit came in and asked what we were doing. I explained and he left the classroom without saying a word. Some time later I was summoned to the Komsomol committee and expelled from the Komsomol at a Komsomol meeting. Then there was the town Komsomol committee meeting that I still remember at which I was expelled. I couldn't understand why they expelled me, when I was just willing to help someone. 'How could you help an enemy of the people 20?' I had tears in my eyes. I sincerely wanted to help a person and they shut the door in my face.

The Germans attacked the USSR in 1941 and Kishinev was bombed at 4am on 22nd June. One bomb hit a radio station antenna post in a yard on the corner of Pushkin and Sadovaya Streets. At first I thought it was a practice alarm. A few days later Mama said their hospital was receiving the wounded from the front line. We lived two blocks away from the hospital, and I rushed there to help carry the patients inside. Kishinev was bombed every day at about 11am.

I finished the technical school on 24th June. The school issued interim certificates instead of diplomas because of the wartime. I got an assignment [see mandatory job assignment in the USSR] 21 to Kalarash [50 km from Kishinev]. I took a train to the town and went to the house maintenance department. There was a note on the door: 'All gone to the front.' I went back to Kishinev on a horse-drawn wagon. I arrived in the early morning. A militiaman halted me on the corner of Armianskaya and Lenin Streets. He checked my documents and let me go. This was 6th July and on the following day I was summoned to the military registry office that was forming groups of young guys to be sent to the Dnestr in the east. In Tiraspol we joined a local unit and moved up the Dnestr. My former co- students and friends Lyodik [short for Leonid] Dobrowski and Ioska [short for Iosif] Muntian and I stayed together. We crossed the Dnestr south of Dubossary. German bombers were fiercely bombing the crossing. We arrived at a German colony 22 in Odessa region where we stayed a few days. Then we joined another group from Tiraspol and moved on. On our way we mainly got food from locals.

One night, we arrived at Kirovograd [350 km from Kishinev, today Ukraine] where a restaurant was opened for us and we were given enough food to eat to our hearts' content. Then we were accommodated in the cultural center. We had enough hours of sleep for the first time in many days. On Sunday young local people came to dance in the yard. A few of us joined them. I asked a pretty girl to dance, but she refused. I asked another girl, but she refused, too. When the third girl refused to dance with me, I asked her 'Why?' and she replied, 'because you are retreating.'

The next morning we got going. For two months we were retreating from the front line. At times we took a train, but mainly we went on foot. We arrived at a kolkhoz 23 in Martynnovskiy district, Rostov region. We stayed there for a month. I went to work as assistant accountant. Throughout this time I was dreaming about joining the army. Dreaming! In October, when the front line approached, we were summoned to the military registry office and then were assigned to the army. Lyodik, Ioska and I remembered that we were Bessarabians [the Soviet commandment generally didn't conscript Bessarabians, former Romanian nationals], since we came from Tiraspol, another Soviet town, we kept silent about it; we wanted to join the army!

Ioska and I were assigned to the front line forces and Lyodik joined a construction battalion. Construction battalions constructed and repaired bridges and crossings. After the war I got to know that Ioska survived and Lyodik perished. I was sent to Armavir [today Russia]. We received uniforms: shirts, breeches, caps and helmets. We also received boots with foot wrappings that were to be wrapped around the calves, but then they slid down causing much discomfort. We received rifles and were shown how to use them. After a short training period I was assigned to an infantry regiment, mine mortar battalion, where I became number six in a mortar crew consisting of the commander, gun layer, loader and three mine carriers. A mine weighed 16 kilos: so it was heavy and for this reason three carriers were required. Some time later I was promoted to the commander of a crew since I had vocational secondary education. Our battery commanding officer was Captain Sidorov, a nice Russian guy of about 30 years of age. It may seem strange, but I have rather dim memories about my service in the front line forces. It's like all memories have been erased!

In 1942 I was wounded in my arm near Temriuk [Krasnodarskiy Krai, today Russia]. I was taken to a hospital in Anapa. Six weeks later I returned to the army forces. However, I didn't return to my unit. Instead, I was sent to a training tank regiment in Armavir where I was trained to shoot and operate a tank. I could move a tank out of the battlefield if a mechanic was wounded. All crew members were supposed to know how to do this. A tank crew consists of four members: commander, loader in the tower, a mechanic on the left and a radio operator and a gunman/radio operator on the right at the bottom of the tank. The radio operator receives orders and shots. The commander of the tank fires the tower gun. I was the loader, 'the tower commander', as tank men used to call this position. Tank units sent their representatives to pick new crew members to join front line forces and replace the ones they had lost: 'sales agents' as we called them.

I was assigned to a tank regiment near Novorossiysk. The commander of my tank, Lieutenant Omelchenko, was two or three years older than me. He had finished a tank school shortly before the war. The tank and radio operators were sergeants and I was a private: we were the same age. They were experienced tank men and had taken part in a number of battles compared to me. Omelchenko was Ukrainian and the two others were Russian. At first I noticed that the others were somewhat suspicious of me, but then they understood I was no different from them. We were in the same 'box' and we got along well. I was afraid before the first combat action, but I didn't show it so that I wouldn't give them a chance to say: 'Hey, the Jew is frightened'. I didn't notice anything during the first battle since all I did was load the shells to support non-stop shooting. I was standing and placed the shells into the breech, heard the click of an empty shell and loaded the next one. All I heard was roaring, this maddening roaring. I might have got deaf if it hadn't been for the helmet. The battle ended all of a sudden, and it all went very quiet. I don't know who won, but the Germans had gone. When we were on our way back to our original position, the manhole was up and we were getting off the tank. I heard the sound of a shot and fell.

The bullet hit me in my lower belly and passed right through my hip. I was taken to the medical battalion where they wanted to give me food, but I knew that I wasn't supposed to eat being wounded in my belly - I knew from Mama, who was a medical nurse. The doctor examining me decided he knew me. He thought I had been his neighbor in Odessa. I was taken to the rear hospital in Grozny by plane. This was a 'corn plane' [agricultural plane], as people called it, and the wounded were placed in a cradle fixture underneath the plane. I remember that the hospital accommodated in the house of culture [alternative name for cultural center], was overcrowded and the patients were even lying on the floor. I was put on a bed since I was severely wounded. A few days later I got up at night and went to the toilet. I started walking and was on my way to recovery. After the hospital I was sent to a recreation center where Shulzhenko gave a concert on the second floor. [Shulzhenko, Claudia Ivanovna (1906-1984): Soviet pop singer, whose name is associated with the start of Soviet pop singing] I went to the second floor. I can still remember the stage and Shulzhenko in a long concert gown. She sang all these popular songs and one of them was 'The blue shawl' [one of the most popular wartime songs]. There was a storm of applause!

I received my first letter from Central Asia from my girlfriend whom I had met in Kishinev before the war. Her name was Neta [Anneta]. She somehow managed to get to know my field address. Neta also gave me my parents' address. She wrote in her first letter that my parents had evacuated to Central Asia and were staying in Kokand, Uzbekistan. Mama worked as an assistant doctor and Papa was a teacher of mathematics at a local school. They wrote to me once a month. The field post service was reliable. At least, the letters made it to me wherever I was. A postman was always waited for at the front line. I don't know about censorship, but I wrote what I wanted. My parents described their life in evacuation. When Kishinev was liberated in 1944, they returned to Moldova. Neta and I corresponded, and I visited her when I returned after the war, but I was already married by then.

When I recovered I was assigned to a reserve tank regiment. I stayed there a month before I was 'purchased'. We were to line up, when 'purchasers' visited us and once I heard Kusailo saying, 'this zhyd [abusive of Jew] will never join a tank unit,' but I did, and he and I were in the same SAM [mobile artillery regiment] unit where I stayed for over a year. A mobile artillery unit is very much like a tank, but it has no circulating tower on top of it. It was a 76-mobile unit with a 76-mm mortar. This was one of the first models of mobile units. Lieutenant Chemodanov was my commanding officer. I have very nice memories about this crew and our friendship. I was wounded again and followed the same chain of events: hospital, reserve unit and then front line unit again.

In summer 1943 I joined the [Communist] Party. The admission ceremony was literally under a bush: the party meeting was conducted on a clearing in the wood. I think it was at that time that I got an offer from the special department to work for SMERSH 24. I'd rather not talk about it. Actually, there is nothing to talk about. As far as I can remember, I provoked this myself. I always said I was interested in intelligence work. I was young and must have been attracted by the adventurous side of this profession. This must have been heard by the relevant people. I was given a task: two soldiers had disappeared from our unit and I was supposed to detain them, if I ever met them... This didn't last more than a year, but I must say that spies are quite common during the war. No war can do without intelligence people.

I served in the 84th separate tank regiment for the last two years of the war. I joined it in late 1943, when the Transcaucasian front was disbanded and we were assigned to the 4th Ukrainian front. We had T-34 tanks that excelled German tanks by their features. I was an experienced tank man. We were very proud of being tank men. Air Force and tanks made up the elite of the army. Tank men usually stayed in the near front areas and were accommodated in the nearby settlements. During offensives we moved to the initial positions from where we went into attacks. Sometimes tanks went into attacks with infantry, but we didn't know those infantry men. My tank was hit several times, but fortunately there was no fire. Perhaps, I'm wrong here and other tank men would disagree, but I think if there was an experienced commander of the tank, the tank had a chance to avoid being set on fire. The thing is: if a tank is set on fire, what's most important is to get out of the tank. The manhole was supposed to be closed and the latch was to be locked and this latch might get stuck. We closed the manhole, but never locked it. On the one hand it was dangerous, but on the other, it made it easier to get out of the tank, if necessary. The tank might turn into a coffin if the latch got stuck. Germans shot bullets at us and we believed that if we heard a bullet flying by, the next one was to hit our tank. Then we evacuated from the tank and crawled aside before the tank became a convenient target or hid behind the tank, if there was no time left to crawl to a hiding.

I had a friend who was a loader in another crew. I don't remember his name, but I remember him well. He was Russian. When we were fighting in Ukraine he perished in a battle, when we were approaching Moldova. Some time later his mother, who was a military correspondent, visited us to hear how he had perished. She found me since he must have mentioned my name in his letters. When she started asking me the details, I was shocked knowing that she specifically arrived to hear the details of his death. In 1944, when our regiment was fighting within the 4th Ukrainian Front, the Soviet army entered Moldova. I had very special feelings about my homeland. I knew Romanian, and when we were in the woods the others sent me to nearby villages to exchange gas oil for wine. Gas oil was our tank fuel. The villagers were happy to have it for their kerosene lamps. And we were twice as happy since Moldova was known for making good wine.

Major Trubetzkoy, chief of headquarters of our regiment, perished in Moldova. He was everybody's favorite in the regiment. He was young, 29 years old, brave and good to his subordinates. He was cultured and rather aristocratic, I'd say. I even think, he must have come from the family of Trubetskoy. [Editor's note: The Trubetskoy family, an old family of Russian princes (14th-20th century), gave birth to many outstanding statesmen and scientists.] He was killed by a German sniper when he was riding his motorcycle going to the headquarters. He had all of his awards on though he had never worn them all before. Colonel Chelhovskoy, our regiment commander, followed the tanks on the battlefield on his motorcycle. The commander of the regiment intelligence was Captain Dyomin. Our regiment was involved in the Iasi/Kishinev operation [From 20th-29th August 1944 the Soviet troops liberated Moldova and Eastern Romania. Romania came out of action and on 24th August its new government declared war to fascist Germany.] All types of forces were involved in this operation. Our tank regiment passed Kishinev and its suburbs, and we could see how ruined the town was.

After the Iasi/Kishinev operation we entered Bulgaria via Romania. People welcomed us as liberators. On 24th September 1944 we arrived in the town of Lom. It was hot and I jumped out of the tank without my shirt on. A bunch of Bulgarian girls surrounded me. One of them gave me a bunch of field flowers. Then the bravest of them, Katia, asked me to get photographed with them. Her boyfriend took a photo of us. I gave Katia the address of my parents at their evacuation spot and she sent them the photo. From Bulgaria we moved on to Hungary across Romania. In Hungary our tank regiment was involved in battles near Szekesfehervar and Dunaujvaros on the Danube River. Our crew changed within a couple of days: someone was wounded or killed, a commander or radio operator. I only remember Nikolai, the tank operator. I remember the names of our regiment commander or chief of staff, but not of those who were with me in the tank: this is strange, but that's how it happened. In 1945 we moved on to Czechoslovakia and then returned. It should be noted that we were given a warm welcome in Czechoslovakia, but they were also happy to see us leaving again. Or at least that's the impression I got.

In Hungary I was slightly wounded again and that's when I met my future wife Lidia Zherdeva in the hospital. She was a medical nurse in the army. Lidia came from Kharkov [today Ukraine]. Her mother stayed on occupied territory during the war. Her mother was mentally ill and Lidia thought she had perished, when one day, shortly before demobilization, she heard from her mother. She felt like putting an end to her life because it was extremely hard for her to live with her insane mother. She took morphine, but the doctors rescued her. We were together, though we weren't officially married. It was a common thing at the front line. Occasionally there were orders issued in the regiment and that was it about the official part.

I celebrated the victory in Nagykoros, a small town near Budapest. We actually expected it... In the morning of 9th May we were told that the war was over. What joy this was! I cannot describe it. We didn't shoot in the air since we had no guns, only carbines in tanks, but we hugged each other and sang! In the evening we drank a lot. Our regiment was accommodated in Budapest. Our radio operator, mechanic and I were accommodated in one woman's house. The Hungarians were good to us, particularly the women. The Hungarian language is difficult and we mainly used sign language. One of us had a better conduct of Hungarian than the others and translated for us.

In late 1945 demobilization began. There was an order issued to demobilize those who had vocational secondary education first. I was a construction man and had a certificate on the basis of which I was demobilized in January 1946. Lidia and I moved to Kishinev. My parents were back home and my father taught mathematics at school. They lived in a small room on Sadovaya Street. I went to the executive committee to ask them about a job and some accommodation, but they replied, 'there are thousands like you. And there are also invalids.' One of my father's former students left Kishinev, and my wife and I moved into his hut on Schusev Street. Later we obtained a permit to stay there. This former student's father was working in the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Moldova and helped me to get employed by the industrial construction trust. In February 1946 I was already working as a foreman at the construction of a shoe factory on Bolgarskaya Street. In 1949 my mother died. We buried her in the Jewish cemetery, but not according to the Jewish ritual from what I remember.

In 1944 my cousin brother Abram Shusterman returned from evacuation. He had been in Central Asia with his mother and nephews. Some time later Abram was exiled to the North: he told a joke about the government and someone reported on him to the KGB 25. Later he was allowed to settle down in Central Asia. After Stalin's death [5th March 1953], he and his wife visited us in Kishinev. They had no children. He was my only relative, who thought he had to take care of me. I have no other relatives. He died in Central Asia, but I don't remember in what year.

I didn't live long with my first wife. I fell in love with Lubov Berezovskaya. She was an accountant in our construction department. I think she was the most beautiful woman I've ever met in my life. I was offered the position of site superintendent at the construction of a food factory in Orhei. At first I refused, but when I heard that Berezovskaya was going there to work as an accountant, I changed my mind. We moved to Orhei together and got married in 1947. Our son Sergei was born there. My second wife was Russian. She was born in Kharkov in 1925. She moved to Kishinev after the war with her mother, Olga Antonovna Chumak. Her father, Boris Berezovskiy, died before the war. Olga Antonovna was a worker at the shoe factory in Kishinev. When we met, Lubov only had secondary education, but later she graduated from the Faculty of Economics of Kishinev University. She was promoted to chief accountant of the construction department.

There was a building frame on the construction site. Our office was accommodated in a small building next to it. In August 1950 the director of the construction department organized a meeting dedicated to Kotovsky 26. I went to Kishinev at this time. We were driving on a truck and I was struck by the color of the sky over Orhei: it was unusually green. My co- traveler from a village said, 'I've never seen a sky of this color before.' When I arrived at the construction department in Kishinev the people had scared expressions on their faces. It turned out that after I left Orhei a storm broke and the frame of this building collapsed over the office. I rushed back to Orhei. When I arrived, I asked, 'Are there any victims?' 'Fifteen.' Later a commission identified that this was a natural force majeure and this was the end of it. The director of the factory, a former KGB officer, resigned and went back to work at the KGB office.

In December this same year the chairman of the Trade Union Committee of the Light Industry reported this accident at the USSR trade union council plenary meeting in Moscow. There was the question: 'Was anybody punished?' 'No.' A week later I was summoned by the prosecutor and didn't return home. I was interrogated for a day, and in the evening I was put in prison. They shaved my head before taking me to jail. I remember entering the cell: 25 inmates, two-tier plank beds. I was so exhausted that I just fell onto the bed and fell asleep. A few days later I was appointed crew leader for the repairs in prison. About two weeks later I was released. The Light Industry Minister, Mikhail Nikitich Dyomin, helped me. He knew everything about the construction of this food factory, and construction men called him a foreman. I remember going home from prison on New Year's Eve with my head shaved.

In April 1951 I was summoned to the Prosecutor's Office. I said to my wife, 'Look, I'll probably need an extra pair of underwear.' This happened to be true. There was a trial. I was convicted and sentenced to three years in jail for the violation of safety rules, and the construction chief engineer, Mikhail Weintraub, was sentenced to three years in jail as well. It turned out I wasn't supposed to allow them to conduct the meeting in this annex. Dyomin arranged for us to be assigned to the construction of the Volga-Don channel [the Volga-Don channel, named after Lenin, connecting the Volga and the Don near the town of Kalach, opened in 1952]. There were mainly prisoners working on the construction of this channel. We lived in barracks for 20-30 inmates.

Since I was a foreman and supposed to move around visiting the sites, I was released from the convoy. I could move around within an area of 80 kilometers. I could also stay overnight in a guard house on the construction site. My wife often visited me. Fortunately, the chief engineer of the district knew me from back in Moldova. He worked at the construction of the Dubossary power plant and we met in Kishinev. When Lubov came to visit me she stayed in a room in his apartment for a month. A year later I was released, the conviction was annulled and I was awarded a medal 'For outstanding performance.' When I came back home, I was sent to work at the CD-8 [construction department]. However, when I wanted to restore my membership in the party, I was told: 'You can join the party again, but you can't restore your membership.' This hurt me and I gave up. I didn't avoid the war or prison in my life...

I was arrested at the time of the campaign against 'cosmopolitans' 27, but I don't think that Mikhail or I fell victim to this campaign. The period of the Doctors' Plot 28 started in 1953, when I returned to Kishinev. I heard talks that Jews were bad and would kill, poison people etc., but there were no official actions of this kind. I can't say whether any doctors were fired at that time.

I remember Stalin's death well. I cried. I heard it either early in the morning or in the evening, because it was dark, when I was at home. Our friends felt the same. At war the infantry went into attacks shouting, 'For Stalin! For the Motherland!' I didn't believe what I heard during the Twentieth Party Congress 29 in 1956, when Khrushchev 30 reported facts that we had never known about. I don't think I believe it even today. I cannot believe it, it's hard to believe, you know. When a person has faith in something it's hard to change what he believes in. If I had seen it with my own eyes..., but I only know what I heard. It's hard to change what one believes. I still have an ambiguous attitude to it.

In 1954 our second son, Oleg, was born. When we moved back from Orhei we received a two-bedroom apartment. We bought our first TV set, 'Temp', with a built-in tape recorder and a wireless. I was offered a plot of land to build a house, but neither my wife nor I wanted it. My mother-in-law lived in a one-bedroom apartment. We exchanged her one-bedroom and our two- bedroom apartment for a three-bedroom apartment in Botanica [a district in Kishinev]. My mother-in-law lived with us, helping us about the house and with the children. We hardly observed any Jewish traditions in our family. I entered the extramural Faculty of Industrial and Civil Construction of Moscow Construction College. I defended my diploma in Moscow. By the time of finishing the college I was a construction site superintendent. A construction site included two to three sites. I was in charge of the construction of a few apartment buildings, kindergartens, a shoe factory, a leather factory, a factory in Orhei and a fur factory in Belzi. Occasionally, when walking across town I think: this is mine and this one as well.

After my mother died my father married his former student. I don't even want to bring her name back to my memory. I thought this was an abuse of my mother's memory, and I kept in touch with them just for the sake of my father. Though my father's second wife was a Jew, I don't think they observed any Jewish traditions. I don't think my father went to the synagogue after the war, not even at Yom Kippur, but we lived separately and I cannot say for sure. My father died in 1961. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery, but I cannot find his grave there.

Our family was very close. Our sons got along well. In 1954 Sergei went to the first grade. He studied in a general secondary school. Oleg was seven years younger and Sergei always patronized him. He was in the seventh grade, when Oleg started school. After school Sergei finished the Electrotechnical and Oleg the Construction Faculty of the Polytechnic College. My sons adopted my wife's surname of Berezovskiy. They are Russian and there was no pressure on my wife's side about this. I gave my consent willingly since it was easier to enter a higher educational institution with the surname of Berezovskiy rather than Rozenfain. As for me, I never faced any anti-Semitism at work. Everything was just fine at my workplace. Always!

My wife Lubov was a kind person. She was always kind to people. We lived almost 50 years together and not a single swearword passed her lips. We never had any rows and I believe I had a happy family life. We spent vacations separately. Starting in 1959 I went to recreation centers and sanatoriums and the costs were covered by trade unions at work. My wife also went to recreation centers, but not as often as I did. I traveled to Odessa, Truskavets, Zheleznovodsk. I also went to Kagul, Karalash and Kamenka recreation homes in Moldova. My wife and I went to the cinema together and never missed a new movie. I knew a lot about Soviet movies and knew the creative works of Soviet actors and producers. I liked reading Soviet and foreign classical literature. I had a collection of fiction: I still have over two thousand volumes. I liked Theodore Dreiser [1871-1945, American novelist]: 'The Financier', 'Titan', 'Stoic' and I often reread these novels. I never took any interest in samizdat [literature] 31. Once I read Solzhenitsyn 32, The Gulag Archipelago, but I didn't like it. Now I read detective stories! I like Marinina [Marinina, Alexandra (born 1957): Lvov-born, contemporary Russian detective writer], but I prefer Chaze [Chaze, Lewis Elliott (1915-1990): American writer].

We celebrated all Soviet holidays at home. We went to parades on October Revolution Day 33, and on 1st May, and we had guests at home. We celebrated 8th March [International Women's Day] at work. We gave flowers and gifts to women and had drinking parties. I congratulated my wife at home. Of course, we celebrated birthdays. We invited friends. There were gatherings of about ten of us when we were younger. The older we got, the fewer of us got together. Some died and some moved to other places. I sympathized with those who left the country in the 1970s. In 1948 when newspapers published articles about the establishment of Israel I felt very excited and really proud. I always watched the news about Israel. I admired the victory of Israel in the Six-Day-War 34. It was just incredible that such a small state defeated so many enemies. I considered moving to Israel during the mass departure, but it wasn't very serious. If I had given it more serious thought, I would have left. I had all possibilities, but I didn't move there because I had a Russian wife.

In the 1970s, when I worked at the construction of a factory of leatherette in Kishinev, I went to Leningrad [today St. Petersburg] on business twice a month. The factory was designed by the Leningrad Design Institute. By the way, Chernoswartz, our chief construction engineer, was a Jew. He moved to Israel in the 1990s with his daughter. His wife had died before. He was ten years older than me and I don't think he is still alive. I love Leningrad and always have. Not only for its beautiful architecture, but also for its residents. I think they are particularly noble and intelligent. This horrible siege [see Blockade of Leningrad] 35 that they suffered! They used to say in Leningrad: you are not a real Leningrad resident if you haven't lived through the siege. They are such good people, really! And its theaters! Once I went to the BDT [Bolshoi Drama Theater] 36, where the chief producer was Tovstonogov [Tovstonogov, Georgiy Alexandrovich (1913- 1989): outstanding Soviet artist], a Jew by origin. When I came to the theater there were no tickets left. I was eager to watch this performance; I don't even remember what it was. It didn't take me long to decide to go to see Tovstonogov himself. I explained who I was and where I came from. He gave me a complimentary ticket. I remember this.

I had a friend in Leningrad. His name was Nikolai Yablokov. He was the most handsome man I've ever seen. He was deputy chief of the Leningradstroy [construction department]. I met the Yablokov family in the 1950s when I was working at the factory construction in Orhei. Nikolai's wife worked on our site in Orhei and he joined her. I met him at the trust and we liked each other. We became friends though we didn't see each other often. He was probably my only close friend in many years. He was a good person, I think. I always met with Nikolai when I went to Leningrad. He knew many actors. One night we had dinner at a restaurant on the last day of my business trip and went for a walk to the Nevskiy [Nevskiy Prospekt, main avenue of St. Petersburg]. This was the time of the White Nights when Leningrad is particularly beautiful. I left and one day later I was notified that Nikolai had died. [White Nights normally last from 11th June to 2nd July in St. Petersburg, due to its geographical location (59' 57'' North, roughly on the same latitude as Oslo, Norway, or Seward, Alaska). At such high latitude the sun does not go under the horizon deep enough for the sky to get dark on these days.]

Some time after Nikolai's death I got a job offer from Leningrad. My application letter was signed up and we were to receive an apartment in Pushkino, but my wife and I decided to stay in Kishinev after we discussed this issue. Everything here was familiar: our apartment, the town, the people we knew, and our sons. Sergei worked at the Giprostroy design institute [State Institute of Town Planning] and Oleg worked at the Giproprom design institute [State Institute of Industry Planning]. My sons got married. My daughters-in-law are Russian: Svetlana, my older son's wife, and Tamara, the younger one's wife. In 1969 my first granddaughter, Yelena, was born, the daughter of Sergei and Svetlana. Then Galina and Tatiana were born. I have five granddaughters. Oleg had two more daughters: Yekaterina and Olga. I worked at the factory of leatherette for 43 years: I worked at its construction and then became chief of the department of capital construction and I still work there.

When perestroika 37 began in the 1980s, I took no interest in politics living my own life. I had no expectations about it. I didn't care about whether it was Gorbachev 38 or somebody else in rule. After the break up of the Soviet Union nothing changed. I kept working, but the procedure was changing. We used to receive all design documents within two to three weeks and we didn't have to pay for them, but now it takes about two years to prepare all documents for the design, longer than designing itself. It also costs a lot. One of my acquaintances, a very smart man, who had worked in the Gorstroy, wrote a very detailed report where he described what needed to be done to return to the appropriate system of document preparation. [Editor's note: Gorstroy is the Russian abbreviation for 'gorodskoye stroitelstvo,' literally 'city building/construction,' a municipal organization responsible for construction at the city level.] He was fired within a month. I receive a pension and salary. So, I'm a 'wealthy' man. However, to be honest, my older son supports me a lot. Half of my income comes from him.

My wife died in 1998. After she died, my younger son Oleg, his family and I prepared to move to Israel. We had our documents ready when he died all of a sudden [2000] and we stayed, of course. I sold my apartment and moved in with my daughter-in-law and granddaughters to support them. My granddaughters are in Israel now and are doing well. Yekaterina, the older one, lives near Tel Aviv, she's served in Zahal [Israel Defense Forces]. Olga moved there last summer [2003]; she lives in the south and studies. They are single. Another tragedy struck our family in 2002: Galina, Sergei's second oldest daughter, committed suicide. Yelena, the older daughter, is a doctor. She lives in Rybniza with her husband. She is a gastroenterologist. Tatiana, the younger daughter, is finishing the Polytechnic College. I have my older son left: he is everything I have in life. He is an electric engineer and a very skilled specialist. He has worked in the Giprostroy design institute for over 20 years. When he travels on business I cannot wait till he calls.

Unfortunately, I know little about the Jewish life in Kishinev today. However, I'm deputy chairman of the Council of Veterans of the War of the Jewish Cultural Society. We, veterans, have meetings and discussions in a warm house... We usually sit at a table, and the lady of the 'warm house' receives food products for such parties from Hesed 39. We are close with regards to character and have common interests. I enjoy these meetings. Hesed provides assistance to me like it does to all Jews. I receive food parcels once a month and this is very good for me; this assistance constitutes 20-30 percent of my family budget. Hesed also pays 50 Lei for my medications. I can also have new glasses once a year. I'm very grateful to international Jewish organizations for this.