Izsák Sámuel

Életrajz

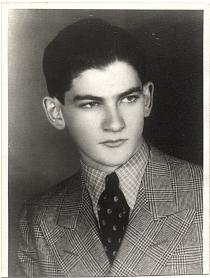

Izsák Sámuel jó megjelenésű, régi vágású nyugdíjas orvostörténész. Az értelmiségi ember éleslátása és törekvése a körülötte és vele történő események okának, értelmének felkutatására Izsák Sámuelre is jellemző. Az általa megélt és elmesélt élettörténet elsősorban önmagáról szól. A környezetéről (család, barátok, ismerősök) alig hajlandó beszélni, a moralitásra, a más magánügyeibe való beavatkozás helytelenségére hivatkozva. Mindennapjait most is a kutatómunka, az írás tölti ki. A kolozsvári zsidó hitközség életében nem vesz részt. Sem ő, sem felesége nem tagjai a hitközségnek, zsidóságukat viszont kihangsúlyozzák. A központi fekvésű lakásában alig utal valami arra, hogy nem keresztények lakják. Az egyszerű berendezés olyan értelmiségi családra utal, amelynek nem az anyagi, hanem a szellemi értékek jelentenek prioritást. A dolgozószoba könyvei, íróasztala, Szobotka Endre szobrász, festőművész képei a falon, egy zongora a lakás hangulatának meghatározói.

Apai részről az én nagyszüleim gazdálkodók voltak Mezőszabadon, egy Marosvásárhely környéki faluban. A falu 12 kilométerre fekszik Marosvásárhelytől. Apai nagyapámat úgy hívták, hogy Izsák Sámuel. A születésére nem tudok határozottan válaszolni, csak azt tudom, hogy a családi legenda szerint 1914-ben halt meg és azután egy évre rá születtem én, 1915-ben, és az ő nevét viselem. A nagyapám, egy időben, a 19. század vége felé, egy éven át Mezőszabad bírája volt, amit ma polgármesternek neveznek. Úgy volt, hogy választás alkalmával az addigi bírót le kellett váltani és a következő választásig a nagyapám töltötte be a tisztséget. Kitűnően vezette a falut, az alatt az idő alatt rend volt a faluban. Nem voltak verekedések a fiatalok között. A falusiak tisztelettel gondoltak rá, megbecsülték, mert támogatta őket. Nagyon szép kapcsolat alakult ki a nagyapám és Mezőszabad község lakói között, akik egyébként románok voltak. Mezőszabad egy román falu. Úgy tudom, hogy az ő családja volt az egyetlen zsidó ebben a faluban. Nem tudok róla, hogy bármilyen egyesületnek vagy pártnak tagja lett volna a nagyapám. Azt sem tudom, hogy egyáltalán volt valamilyen politikai meggyőződése.

Az apai nagyanyám lányneve Simon Regina volt és a férje halála után özvegy Izsák Sámuelné név alatt ismerték. 1864 körül született. Az apai nagyszüleim anyanyelve magyar volt. Teljesen közép-európai divat szerint öltözködtek. Szép és egészséges emberek voltak. A nagyapámnak fiatal korában volt egy kis szakálla. Van egy nagyon régi, múlt század végi képem nagyanyámról és nagyapámról, ahol látszik, hogy teljesen európaiasan voltak öltözködve. Civilizáltan éltek, gondozták magukat. A 20. század elején beköltöztek Marosvásárhelyre. Egy ideig bérlakásban éltek a nagyszüleim, azután vettek egy emeletes házat maguknak nem messze a város központjától, a Kisfaludi utcában. Az alsó emeleten lakott az Izsák család. Hogy a felső emeleten ki volt, arra nem tudok válaszolni. A háznak abszolút modern berendezése volt, a kor divatja szerint. Úgy emlékszem, legkevesebb négy szoba volt a mellékhelyiségeken kívül. Nem emlékszem rá, hogy lett volna vezetékes víz. Emlékszem, hogy a nagyszüleimnek volt egy székely cselédlányuk is.

Vallásosak voltak, egész biztos, hogy megtartották az ünnepeket. A nagyanyám rendszeresen járt templomba. Azt hiszem, hogy a nagyanyám ortodox volt. De a nagynénéim, nagybátyáim és az apám is lassan-lassan valamennyien neológgá 1 lettek, elvilágiasodtak és már kevésbé voltak vallásosak. Nem tértek át neológnak, de amikor alkalom nyílt akkor neológ templomba jártak. Persze erre Marosvásárhelyen nem volt lehetőség, mert csak ortodox és status-quo 2 zsinagóga volt, de nem maradt mindenki Marosvásárhelyen. Szétszéledtek Erdélyben. Nem emlékszem, hogy például apám, Marosvásárhelyen ortodox templomba járt volna. Miután a családunk Nagyváradra költözött, ahol a neológia dominált, ott neológ templomot látogatták a szüleim, én kevésbé jártam. Aztán átköltöztünk Temesvárra ott is neológ templomba jártak.

Gyermekként több ízben voltam a nagyanyámnál, nagynénéimnél és nagybátyáimnál, Marosvásárhelyt. Rendszerint szombatonként meg voltam híva az apai nagyanyámhoz, nála ebédeltem. Meg kellett várjam a templom előtt, mert ő minden szombaton délelőtt templomba járt. Nekem nem volt kötelező, ezért vártam inkább kint. Kijött a templomból, együtt mentünk haza és útközben kérdezgette, hogy „Te miért is szeretsz hozzám jönni? Azért jössz hozzám mert szeretsz?” Én azt mondtam, hogy azért megyek a nagymamához, mert nagyon jó az ebéd. Persze ő ezt sértésnek vette. De hát a gyermeki száj mit mondhat egyebet?

Több nagybátyám és több nagynéném volt. Apám nővérei a következők voltak: Sári, Erzsi, Teréz és Antónia. Az Izsák Sári nagynéném 1887-ben született. Színműveket irt. Ezek közül többet ellő is adtak Marosvásárhelyen. Címeikre és hogy milyen színtársulat adta elő őket már nem tudok visszaemlékezni. Emlékszem viszont az egyik előadásra, amely a marosvásárhelyi kultúrpalota előadó termében zajlott. Ott voltunk az egész családdal. Én még gyermek voltam. Csak arra emlékszem, hogy a darabot tapsvihar követte és nagynénémet a függöny elé tapsolták és virágkosarakat kapott. A közönség kifejezte a tiszteletét. Nem volt férje. Egyébként egyik nagynénémnek sem volt családja és mind Auschwitzban pusztultak el. Apám nővérei nem tudom milyen szakmát tanultak ki, viszont tudom, hogy rendkívül szép fehérnemű-varrást és goblent készítettek megrendelésre. Marosvásárhely főterén volt egy kiváló kézimunka vállalat, még exportált is, és apám összes nővére annak dolgozott. A cég nevét nem tudom. Izsák Teréz 1896-ban született. Mást nem tudok róla, csak azt, hogy Auschwitzban halt meg. Izsák Antónia volt a legfiatalabb apám testvérei közül, ő 1904-ben született. Auschwitzban halt meg.

A fiuk közül apám volt a legidősebb, majd utána következtek: József, Jenő, Béla, Gyula. Ezek voltak a nagybátyáim. Izsák József Marosvásárhelyen volt tisztviselő az úgynevezett petróleum gyárban. Egy rendkívül művelt ember volt, különleges nyelvérzékkel rendelkezett. Ő nyolc–tíz nyelven írt és beszélt. Ismerte a keleti nyelveket: perzsa, török, ivritet. Tudott románul, olaszul, németül, franciául. Rendkívül gazdag könyvtára volt. Minden alkalommal, mikor nála jártam, könyvet ajándékozott nekem. Családja nem volt. Úgy tudom, hogy Kistarcsáról deportálták, politikai okokból. Hogy pontosan mik voltak ezek az okok, nem tudom. Auschwitzban pusztult el, 1944-ben.

Izsák Jenő Kolozsváron élt, ő is tisztviselőként dolgozott. Volt valamilyen kereskedelmi ügynöksége, ami az övé volt. A feleségét Jánosi Annának hívták, aki úgy tudom, református volt. A lányuk, Éva, egyszer azt állította nekem, hogy Anna áttért a nagybátyámmal való házasság után zsidónak, de én erről nem tudok semmit. Nem voltak gazdagok, de jó módúak voltak. Jenő nagybátyám is, akár József, szeretett olvasni. Volt neki is egy kisebb házi könyvtára, főleg modern irodalmi művekkel. Orvostanhallgató koromban vasárnaponként meg voltam híva hozzájuk ebédre, mint diák. Azért vasárnap, mert még járt a nagybátyámékhoz ebédelni egy rokonuk, egy magyar fiú, aki egyébként nekem kollégám volt és vele erre a napra volt megegyezve. A lányuk, Éva, Marosvásárhelyen végezte el az orvosi egyetemet, majd az 1930-as években férjhez ment egy doktor Herczeg nevű zsidó orvoshoz, itt Románia területén, és kivándoroltak Izraelbe. Éva ma is ott él Izraelben, Rishon Le Zionban. Kiváló orvosnő volt, a marosvásárhelyi orvosi fakultáson tanulta a szakmát. Most már nyugdíjas korban van, hogy hány éves azt már nem tudom megmondani. A vészkorszak alatt Anna nagynéném rejtegette Jenőt a hatóságok elől. Hogy milyen módon, arra nem tudok válaszolni, csak azt tudom, hogy elrejtette és sikerrel. Nehéz dolog kellett legyen. Jenő nagybátyám megmenekült a deportálásoktól, és aztán itt halt meg Kolozsváron. Az évet nem tudom pontosan megmondani.

Izsák Béla úgy tudom, gazdálkodó ember volt. Talán szőlőse is lehetett. Volt felesége, családja, Marosvásárhelyen éltek. Béla jóval a deportálások előtt halt meg valamilyen betegségben. Pontos értesülésem nincsen arról, hogy mi okozta a halálát. A felesége zsidó származású volt, 1898-ban született. Eszternek hívták. Volt két gyermekük, Izsák István és Izsák Kati. Nagybátyám feleségét, Esztert és lányát, Katit a holokauszt ideje alatt Auschwitzba deportálták. Eszter ott pusztult el, a lánya viszont megmenekült. Kati nem sokkal hazatérése után Izraelbe vándorolt. Izsák István a holokauszt alatt munkaszolgálatos volt. A vészkorszak után, Marosvásárhelyen megnősült. Újságíróként dolgozott, úgynevezett közíró volt, egészen a haláláig.

Izsák Gyula 1899-ben született. Családot nem alapított. Magántisztviselő volt. Nagyon korán elkerült Vásárhelyről, különböző erdélyi vállalatoknál dolgozott. Kiváló szakértője volt az úgynevezett fafeldolgozó raktáraknak. Úgy emlékszem, az egyik alkalommal Facsárdon volt tisztviselő, ugyancsak faraktárnál. 1940-ben, amikor Észak-Erdélyt elszakították Dél-Erdélytől [amikor a magyar éra kezdődött] 3, az én Gyula nagybátyám hazatért az akkori munkahelyéről Észak-Erdélybe, Marosvásárhelyre. 1944-ben deportálták, Auschwitzban halt meg.

Apám, Izsák Izsák 1885-ben született, Mezőszabadon. Ott iskola nem lehetett, valószínűleg tartom, hogy vagy magánúton végezte az elemit, vagy bevitték Marosvásárhelyre. Sem héderbe, sem talmud-tórába nem járt. Az érettségit, a felsőbb osztályokat, Brassóban járta ki. A brassói Felső Kereskedelmi iskolának volt a diákja és ott is érettségizet. Meg is őriztem az érettségi bizonyítványát. 1901 júniusában tette le az érettségit. Véleményem szerint a tanárai elfogultak voltak, ugyanis nem szabad elfelejteni, hogy apám zsidó volt. Tizenkét tantárgy közül hetet jelessel végzett – mindezek ellenére jó érettnek nyilvánították, nem pedig jelesnek. Román nyelvből is jeles volt. Apám, hát ugye magyar anyanyelvű volt, de románul már gyermekkorában megtanult. Jól beszélt németül is. Valami keveset tudott olaszul és franciául is, de beszélni nem tudott. A szülei azért küldték különben Brassóba, hogy tanuljon meg németül. Miután elvégezte a felsőkereskedelmi iskolát, banktisztviselő lett egy marosvásárhelyi Agrár Bank nevű pénzintézet ludasi fiókjánál. Innen áthelyezték a bank sepsiszentgyörgyi kirendeltségéhez. Ekkor már meg volt házasodva. Sepsiszentgyörgyről behívták Vásárhelyre, a bank központjába és a bank egyik főtisztviselője, egyik igazgatója lett. Az apám nem volt vagyonos soha. Ő nem volt üzletember, nem voltak neki kereskedelmi hajlamai. Jövedelméből viszont meg tudtunk élni.

Az anyai nagyszülők közül én csak a nagyapámat, Legmann Rudolfot ismertem jobban. Ő 1856 körül született. Nagyanyámra, Legmann Rózáliára (született 1878-ban) alig emlékszem, tíz éves voltam, amikor meghalt. Nagyapám egy Kolozsvár melletti román faluban, Drágban volt gazdálkodó. Drág körülbelül 40 kilométerre fekszik Kolozsvártól, északnyugati irányban. Saját- és bérelt földön gazdálkodott. A gazdaságban a család mellett természetesen béresek is dolgoztak, akik a faluból kerültek ki. Kiváló baráti kapcsolatban élt a falu román ortodox (görög-keleti) papjával és a falusi emberekkel, akik nem felejtették el nagyapám emberségét: az első világháború alatt nagyon sok férfit elvittek katonának a faluból és az özvegyeiknek nagyapám támogatást nyújtott, búzalisztet, málélisztet adott nekik. Nem tudnám megmondani, hogy mennyire voltak vallásosak a nagyszüleim. Valószínűnek tartom, hogy a hagyományokat, a hagyományos ünnepeket megtartották és azt is valószínűnek tartom, hogy amikor a kádist kellett mondani a meghalt szülőkért, akkor elmentek a templomba. De pontos értesülésem nincsen ezekről nekem. Az édesanyám ilyen dolgokról nem mesélt, nem mondott semmit. Az anyanyelvük magyar volt.

Gyermekkoromban többször vittek a szüleim hozzájuk látogatóba. Szép falusi házuk volt nagy udvarral, istállóval és kerttel. Nagyon civilizáltan éltek. A ház mögött egy nagyon szép kert volt. A kertben volt egy régi ribizli sor egészen végig. Közte egy kis sétány húzódott. A kert végében egy öreg diófa volt s alatta egy kőasztal. Voltam abban a kis szobában, amelyben anyám a lánykorát töltötte. A szobából nagyon szép kilátás nyílt a kertre. A szobájának ablaka alatt éveken át egy gyönyörű virágszőnyeg volt. Anyám nagyon szerette a virágokat.

Egy nagyon szép gyerekkori emlékem van Drággal kapcsolatban. Nagyapámnál, a ház udvarán őgyelgett egy bivaly bornyú – mert volt bivalyuk, tehenük, lovuk – és én azt hittem, hogy [az állatokkal foglalkozni] az egy gyerekjáték. Odamentem hozzá, az felbőszült, amitől én rettenetesen megijedtem. Elszaladtam és bebújtam egy tyúkketrecbe. Persze jó piszkosan kerültem ki onnan. Mikor a szüleim rám találtak, rögtön levették a ruháimat, megfürdetek – tekenőben persze – és tisztába raktak. Emlékszem egy családi ebédre is. Ott voltak nagyapámnál a rokonok, a szüleim és mi, a testvéreimmel. Mi gyerekek, külön asztalnál ültünk, egy alacsonyabb gyermek-asztalnál. Ugyanazt ettük, mint a felnőttek. A felnőttek bort ittak, nekünk pedig a nagyanyám málnaszörpöt öntött a pohárba szódavízzel.

1925-ben meghalt nagyanyám. Ha nem tévedek mellrákja volt. 47 évet élt. Ezt követően nagyapám eladta amije volt, és a beköltözött Kolozsvárra. Arra emlékszem, hogy nagyapám építtetett magának egy földszintes, egyszerű kis lakóházat és ott élt. Akkoriban úgy hívták azt az utcát, hogy Kun utca. Most ott van a város egyik gyermekklinikája. Ez az utca vezet a Kismezői temetőbe. Annak a háta mögött volt egy kert és abban a kertben van a ház még ma is. Nem tudom, kik élnek most benne. A nagyapám 1938-ban halt meg itt, Kolozsváron. Akkor éppen diák voltam az orvosi egyetemen, a szüleimmel együtt vettem részt a temetésén. Nagyapámat zsidó szertartás szerint temették el, a kolozsvári ortodox temetőbe. Legmann nagyapámnak három gyermeke volt: Ráchel az én édesanyám, Miksa és Irén.

Legmann Miksa nagybátyám Kolozsváron élt, betegségben halt meg deportálás előtt. Nem tudom hány éves lehetett. Azt hiszem, hogy a feleségét, akit Eszternek hívtak, deportálták, de erről nincs egészen biztos információm. Volt két fiuk, József és Pál. Tudom, hogy Pál túlélte a deportálást. Azóta meghalt, de hogy hol azt nem tudom. József is túlélte a deportálást a feleségével együtt. Egy gyermekük született Gyuri, aki Auschwitzban született. Azon hét gyermek közé tartozik, akik Auschwitzban születtek, a deportálás vége felé. Nem tudok részleteket a történetéről. Legmann Irén nagynéném férjnél volt egy darabig. A férjét Deutschnak hívták, nem tudom mivel foglalkozott. Még a két világháború között elváltak, majd Irén egy ideig Bukarestben élt. Később kivándorolt Izraelbe és ott halt meg. Gyermeke nem volt.

Édesanyám, Legmann Ráchel, 1884-ben született, Drágban. Hogyan nevelkedett és hogy hol végezte az elemit, azt nem tudom. A négy polgárit Budapesten járta. A nagybátyjánál lakott. Édesanyám ott nagyon gazdag művelődési életet élt. Színházba járt, folyóiratokat, irodalmat olvasott. Miután hazament Drágba, folyóiratokat járatott az édesanyám Pestről: a Magyar Lányokat és a Kiss József 4 költő által alapított kiváló irodalmi lapot, a Hetet. Édesanyám nagyon szerette a népművészetet, az édesanyám nevelt rá engem is a népművészet szeretettére.

Marosvásárhelyen ismerkedtek meg a szüleim. Volt egy König család Marosvásárhelyen, König Gyula és felesége, Berta, aki anyámnak rokonsága volt. A König Gyulának volt egy húga, a König Róza. Ők figyelmeztették valószínűleg az anyámat, hogy van egy fiatalember, az apám, aki családalapító lehetne. Jó állása van, anyagi szempontból stabil. Valahogy sikerült elérniük, hogy a két fiatal összeismerkedjen, a többi pedig biztos ment magától. Berta néninek öt lánya volt. Egyik lánya, az Iló Ilona néném, egy marosvásárhelyi román nemzetiségű gyógyszerészhez ment feleségül. A lánya már románként nőtt fel. A bátyáim később is, miután Iló néniék az 1930-as években elköltöztek Temesvárra, tartották velük a kapcsolatot. König Gyula jóval a deportálások előtt meghalt, még az 1930-as években. Feleségét, Berta nénit és négy lányát deportálták, ott haltak meg Auschwitzban.

A szüleim 1907-ben házasodtak meg Marosvásárhelyen. Az esküvőről, a házasság körülményeiről nem meséltek semmit. 1908-ban megszületett Izsák Hajnal [1908-1964] nővérem, Sepsiszentgyörgyön. Valószínűleg még ebben az évben, vagy 1909 elején költöztek a szüleim Sepsiszentgyörgyről Marosvásárhelyre. Hajnal elvégezte a zsidó elemit és négy osztályt a vásárhelyi református polgári iskolában. 1909-ben született meg a második testvérem, Izsák Ferenc [1909-1983]. Ferenc a marosvásárhelyi Református Kollégiumba járt középiskolába. Az 1911-ben született Izsák László [1911-1986] testvérem a vásárhelyi román gimnáziumban tanult. A két világháború között a Kolozsváron megjelenő Korunknak 5 volt külső munkatársa. Az írói neve Bálint volt. 1912-ben született Izsák Iván [1912-1977]. Én 1915-ben születtem, Marosvásárhelyen, a család ötödik gyermekeként. Az utánam négy évre, 1919-ben született Izsák Ibolya húgom a legkisebb a testvérek között. Ő kivándorolt a második világháború után Izraelbe, majd onnan Kanadába, a lányához.

Vásárhelynek a zöme magyar lakosságú volt. A központban főként magyarok és zsidók éltek. Én a város kellős-közepén születtem [vagyis a központban laktak Sámuelék gyerekkorában]. Az utca nevére nem emlékszem, de volt ott egy görög-katolikus templom. Annak a háta mögött volt egy házsor és abban a házsorban volt egy úgynevezett Tövisi ház. Általában a házakat a tulajdonosaik után nevezték el, vagy akik ott laktak. A Tövisi házban születtem és úgy emlékszem, hogy ugyan abban a házban laktunk egy ideig. Emlékszem, hogy sok volt a patkány a ház pincéjében és a földszinten. A nagyobb testvéreim üvegeket törtek össze és az üvegcserepeket elhelyezték a pincében hogy a patkányok megsérüljenek, s megdögöljenek. A mellettünk lévő házban volt a híres zsidó származású szemészorvosnak, Dr. Blatt Miklósnak a rendelője. Amikor az elemibe jártam, egy fertőző szemgyulladás járvány volt. Persze a szüleink elvittek minket gyermekeket Blatt doktorhoz, aki kiváló szemész volt. Később, a háború után egyetemi tanár lett belőle Temesváron, majd kivándorolt Németországba. Frankfurt am Main-ban vendégprofesszorként dolgozott. Blatt Miklós kiváló szakorvos író is volt, tudományos munkákat tanulmányokat, dolgozatokat közölt.

A szüleim engem a marosvásárhelyi zsidó elemi iskolába írattak be. Az iskolánk az Iskola utcában volt, ott volt a zsidó templom is. Hazafelé jövet az iskolából, átmentünk rendszerint a marosvásárhelyi egykori Mészáros Közön. A Mészáros Köz egy Vásárhelyi különlegesség volt. Egy utca, ahol csak az egyik oldalon voltak boltok, a másik oldalon a tűzfalak. Egymás mellett sorakoztak a hentes boltok. Zöldre festett fa ajtókkal voltak fedve a bejáratok. Itt egymás mellett több mészárszék volt, később aztán ezeket az üzleteket bezárták. A háziasszonyok ott vásároltak. Hús mellett halat is árultak. Halat a zsidók is ehettek. Az üzletek egyébként magyar tulajdonúak voltak. Egyszer egy mészárszék bejárati kampójára egy 2 méteres harcsa volt kitéve, amit darabokban adtak aztán el. Nagyon meg voltunk döbbenve egy ilyen szörny láttán. Ezek marosi harcsák voltak. Nem tudom, hogy azóta kivadászták-e a harcsákat a Marosból.

Még valamire emlékszem: iskolából hazafelé menet, elhagyva a Mészáros Közt, a Hunyadi úton már, a Vár mellett mentünk el. A Vár okkerre volt festve, és mi ezt a Várat úgy neveztük, hogy Sárga vár. És emlékszem, hogy, elhagyva a várat, éppen akkor a Főtéren ásták a későbbi román ortodox templom alapgödrét, és ott megtalálták az egykori marosvásárhelyi Zenélő Kútnak fából faragott, vezetékeit. Egymásra illesztett, kivájt törzsek voltak. Kiemelték és bizonyára elvitték a múzeumba. Azon a helyen, ahol ma az ortodox templom áll, ott volt a Bodor-féle Zenélőkút. [Bodor Péter, 1788–1849, székely ezermester épitette1816 körül. A kút kupolájába zenélő szerkezetet épített, amely 6 óránként olyan erős hangon zenélt, hogy a szomszédos falvakban is hallották.]

Van egy vásárhelyi antiszemita emlékem. Az iskolából jöttünk haza a Mészáros Közön. Aki Vásárhelyt ismerte, azt tudta, hogy az Iskola utca felöl, a Mészáros Közön át jönnek a zsidó iskolás gyermekek, mivel a zsidó elemi az Iskola utcában volt, a zsinagógától nem messze. Amikor a piacra értünk, – hárman vagy négyen lehettünk, – körülvettek bennünket a csiszlikek. Csiszlik régebben, azt jelentette, hogy inas. Csizmadia inasok voltak, vállukon vitték a csizmát. Körülvettek bennünket és azt kiáltották, hogy „Hep, hep hep”. [Sámuel szerint akkor szoktak így kiáltani, amikor a zsidókkal csúfolódni akarnak.] Különben nem bántottak, csak körülvettek és támadó hangon csúfoltak bennünket. Nem futamodtunk meg, hanem csendben folytattuk utunkat.

A vásárhelyi elemiben volt egy osztálytársam, akire azért emlékszem, mert jártam hozzájuk haza. Paneth Karcsinak hívták. Egy alakalommal elmentem hozzájuk. Az édesanyja fogadott és kérdeztem, hogy „Karcsi nincs-e itthon, mert látogatóba jöttem”. Azt mondta, „Karcsi nincs itthon, de ha meg akarod találni, menj ki a Főtérre, és menjél körbe-körbe az üzleteknél, mert ő ott áll valamelyik kirakat előtt, mert imádja az üzleteket nézni”. És hát kimentem és ott is találtam, s akkor együtt folytattuk a sétát, erre az egyre emlékszem.

Emlékszem arra is, hogy a Főtéren volt akkoriban egy kis sikátor, ami felvezetett a református kollégiumhoz [a mai Bolyai Farkas Líceumhoz]. Ma már megszűnt ez a sikátor, beépítették. Mikor a hetipiac volt, a sikátor Nagypiac felé eső részében voltak a sültet készítő asszonyok. Sült kolbászt, tordai pecsenyét és mást készítettek, finom kenyeret adtak hozzá, és uborkát. Anyámmal voltam éppen akkor a piacon és kértem anyámat, hogy vegyen nekem egy sült kolbászt. Vett is, kaptam hozzá egy szelet nagyon finom házi kenyeret és egy uborkát. Vagy talán savanyú uborka, vagy vizes uborka volt. Nyilvánvaló, hogy nem volt kóser a kolbász, de egyáltalán nem mondta azt anyám, hogy ezt nem szabad megenni, minden további nélkül megvette nekem. Ilyen szempontból a szüleim már túl léptek a vallási előírásokon.

Vásárhelyen, a mi háziorvosunk, a zsidó származású doktor Schmidt Béla volt. Egy ideig szemben laktunk vele. A Rákóczy-lépcsővel szemben van azt hiszem a Petőfi utca, ha nem tévedek. Annak az első házában laktunk mi. A Tövisi házból költöztünk ide. Nem volt a miénk a ház, hanem béreltük. Szemben volt Schmidt Bélának a villája, egy gyönyörű angol stílusú villa, ő építtette. A villa földszintjén volt a pincelejárat. A doktornak volt kocsija, egy homokfutója, és hátul az istálló – úgyhogy ő a betegeihez, ha kihívták, kocsival ment. Kocsisa is volt. Én egy ízben, amikor már a Kemény Zsigmond utcában laktunk, lementem a pincébe, és a fehérnemű-tisztító kazán szélén kőszódát találtam. A kőszóda olyan volt, mint a kandli cukor. Akkoriban volt egy ilyen cukorfajta, amit úgy neveztek, hogy kandli-cukor. Ettem ebből a kőszódából és kiégette a számat. Ösztönösen kiköptem, nem nyeltem le szerencsére. Négykézláb jöttem fel a pincéből, lélegezve, fújva és hűsítve a számat, az egész szám kezdett égni. Akkor anyám megkérdezte, mi történt? Mondtam, hogy a pincében voltam és megettem valamit. Rögtön tudta, hogy mi történt, kocsit hívott és elvitt Schmidt doktorhoz. Schmidt doktor elmondtam, hogy ha lenyeltem volna a kőszódát, akkor nyelőcső szűkülés keletkezett volna, amit nagyon nehéz kezelni, és fájdalmas is lett volna, az étkezést, a táplálkozást is zavarta volna. Egy lisztes pépet készített és azt itatta velem. Mondta, hogy tartsam a számba, de le is nyelhetem, mert lisztből van. Így mentett meg.

Mi nem voltunk túl vallásosak. Szüleim civilizált, közép-európai megjelenésűek voltak, teljesen így is öltözködtek, és viselkedtek. Legfeljebb a családi életben mutatkoztak meg a zsidó vonások, az ünnepekkor. Egyébként szokványos polgári életet éltünk, édesanyám polgári háztartást vezetett. Nem ügyelt a kóser étkezésre. Volt mosónőnk és szolgálólányunk is. Úgy emlékszem, székelyek voltak. A szolgálólányok, amikor elköltöztünk Temesvárra, velünk jöttek, továbbra is az alkalmazásunkban maradtak.

Szüleim olvasott emberek voltak akik szerették az irodalmat, szerették a színházat, szerették a zenét. Volt zongoránk, amin a nővérem zongorázott. Apám megvásárolta a román haladó napi sajtót az Adevărult [Igazság] és a Dimineaţat [Reggel]. Ezek két világháború közötti demokrata napilapok voltak. Állandó olvasója volt apám, a Pesti Hírlapnak. Elő voltunk fizetve a Múlt és Jövőre. Jártak német lapok is, a Die Dame női lap és a Die Voche. A szüleim előfizettek nekünk, gyermekeknek Benedek Elek folyóiratára, a Cimborára. Abból olvasgattuk a mesét. Ezen kívül anyám [gyerek] könyveket is vásárolt nekünk: Benedek Elek meséit, Magyar mese- és mondavilágot, és a Csili Csali Csalavári Csalavért. Így nevelték belénk az irodalom, a kultúra, a művészetek iránti érzéket. Kisasszony is volt egy időben, szász vagy magyar, aki igyekezett németre tanítani bennünket, de nem tanultunk semmit. Apám is, anyám is látta, hogy nincs értelme, mert a gyerekekkel foglalkoznak az iskolában bőven, szabadidejükben pedig ők maguk foglalkoztak velünk. Ezért elbocsátották a kisasszonyt.

Vallásos irodalmat nem olvastunk. Voltak viszont imakönyveink és gondolom, hogy ha voltak, akkor a szüleim használták ezeket is ünnepnapokon. Volt Haggada is, amit húsvétkor szoktak felolvasni. Mivel én voltam a legkisebb fiú a családban, húsvétkor én olvastam fel részleteket a Haggadából, amire aztán apám, az asztalfőnél ülve, válaszolt. Megkérdeztem, hogy ez az éjszaka miért különbözik a többi éjszakáktól: „Ma nistana ha lejla ha ze mi kol ha lejlot?” Apám erre elmondta, hogy rabszolgák voltunk és elhagytuk Egyiptomot, s ennek az emlékére tartjuk ezt az estét. Ez egy örömünnep, mert a rabszolgaságból való szabadulás öröme. Apám felolvasta a tíz csapást is, ami az egyiptomiakat érte, mielőtt belegyeztek volna a zsidók kivonulásába. A csapások felolvasásakor kezünkben tartott borral teli pohárba mártottuk az ujjunkat és lecsepegtettük a földre róla a bort. Ez egy hagyomány volt. Emlékszem, gyermekkoromban volt külön edényünk, amit Húsvétkor használtunk. Ezek ünnepi tányérok voltak. Attól lehetett megkülönböztetni a hétköznapiaktól, hogy színesek voltak. Húsvétkor az asztal meg volt terítve. Előírásos széder este volt. A szó is azt jelenti, hogy rendezett asztal. A széder esték jól meghatározott szertartás szerint folynak le, amit mindig a családfő irányít. Apám az asztalfőnél, mi gyermekek pedig az asztal körül ültünk. Elfogyasztottuk az egykori rabszolgaságra emlékeztető ételeket. Pontos leírását ezeknek az ételeknek nem tudom, de arra emlékszem, hogy volt az asztalon keserűgyökér, ami az élet keserűségét jelképezte. Volt két pászka között dióval készített krém, az a maltert akarta jelképezni. Tudom, hogy volt főt tojás is csak azt nem tudom, hogy a főt tojás mit jelképezett. A főtt tojás a templomi áldozatokra emlékeztet. – A Szerk.] Persze borral fejeződött be ez a része az estének. Mindig igen jó hangulatban teltek el ezek az ünnepek.

Jom Kippurkor elmentek a templomba a szüleim, nem annyira vallásosság, mint amennyire a szüleikre való megemlékezés miatt. Ugyanis Jom Kippur délutánján mondták a kádist, amit ők is elmondtak a szüleik emlékére. Azon a nap böjtöltek is, de mi gyermekek nem tartottuk be az előírásokat. Először is 13 év alatt nem kötelező böjtölni. De az után, miután nagykorúvá lettél azután már minden előírást, legalábbis papíron, respektálni kell. De mi gyerekek nem törődtünk a vallási előírásokkal 13 éves korunk után sem, és böjtkor elmentünk barátainkkal valahová enni. Nem volt szigorú vallásosság a családban, ezért a szüleink nem szidtak össze bennünket.

Nem tudom pontosan, milyen baráti körük volt a szüleimnek Vásárhelyen. Sokat járt anyám a König Berta nénihez. Ennél többet nem tudok. Az én barátaim között természetesen keresztények is voltak. Együtt mentünk kirándulni például a Vásárhely melletti Somos tetőre. Csak mi, gyermekek mentünk, szülői felügyelet nélkül. Vittünk magunkkal gyújtót, üres konzervdobozt, vittünk zöldhagymát, tojást és valami felvágottat is biztosan. Egy kis tűzhelyet csináltunk az erdő szélén, ügyelve, hogy nehogy meggyújtsunk ottan valamit, és nagyon jól éreztük magunkat. És ez többször fordult elő. Előfordult, hogy nyaralni is voltunk. Emlékszem, hogy egy ízben, Szovátára mentünk nyaralni az egész család. [Szováta 67 kilométerre van Marosvásárhelytől.] Más további nyaralásokra nem emlékszem. Bizonyára volt de én nem emlékszem rá.

Egy jobb állást kínáltak az apámnak. A temesvári Timisiana Banknak volt egy fiókja Nagyváradon. Ismerték apámat és értékelték a tudását. Nagyobb fizetést ígértek neki, mint amennyit Marosvásárhelyen addig kapott. Nyilvánvaló, hogy az apám elfogadta, és akkor 1926-ban átköltöztünk Váradra. Nagyváradon, a zsidó iskolában fejeztem be a negyedik elemit, még ebben az évben, 1926-ban.

Váradon nagyon erős kultúrélet volt. Nagyon gyakran tartottak a gyermekek számára a mozikban matinékat, főleg vígjátékokat. Ott ismertem meg Chaplint, Harold Lyodot, Buster Keatont, Stan és Brant [Pant], és Zigottót. A híres nagyváradi Sas palotában volt az egyik legjobb mozi a városban, az első emeleten. A mozi egy nagyon jó módú zsidó családé volt, akinek a tulajdonát képezte a palota. A Sas palotában, kereskedelmi csarnok és szálloda is volt.

Nagyváradi tartózkodásunk alatt töltötte be Iván bátyám a tizenharmadik életévét. A barmicvája az úgynevezett Cion templomban volt, amely egy nagyon szép váradi zsinagóga. Akkor Kecskeméti Lipót volt a rabbi. A bar micvát egy ünnepi ebéd követte nálunk, az otthonunkban, ahová meghívtuk Kecskeméti rabbit is. Emlékszem, hogy a szüleim az asztalfőhöz ültették. Kecskeméti Lipót egy igen neves rabbi családból származott, úgy tudom, hogy az apja is ott volt rabbi Váradon. Az apja híres volt a csodálatosan szép magyar nyelvű prédikációiról, amelyeket meghallgatott Ady Endre 6 is, hogy a magyar nyelv szépségét tanulja, ismerje meg. A Kecskeméti család nagyon elkötelezet volt a magyarság mellett.

1926 ősszén átköltöztünk Temesvárra egy bérlakásba. Annyit tudok, hogy a tulajdonos keresztény volt. 1926 ősszén beiratkoztam a temesvári Zsidó Líceumba. A líceum 1919-es alapítása után néhány évig magyar tannyelvű iskola volt. Azután az új közoktatási törvény következtében román tannyelvre tértek át. Míg gimnáziumba nem kerültem, magyaron kívül más nyelvű irodalmi műveket nem olvastam. Persze ott a gimnáziumban beilleszkedtem a gimnázium programjába és idegen nyelveken is olvastam. Nagyon sok román nyelvű könyv volt feladva. Évről évre mind igényesebb olvasmány volt, előírva és eleget is tettünk ennek. Kisgimnazista voltam, amikor apám megvette Lyka Károly Képzőművészet történetét. Ez egy igen híres könyv. Apám maga is egy kiváló művészettörténész volt. Ez a könyv ébresztette fel bennem a művészettörténet, a művészetek iránti szeretetet és szolgált alapul a későbbi olaszországi éveim alatt kifejlődő képzőművészeti ismereteimnek.

Nagyon szerettem a Zsidó Líceum hangulatát. Minden iskolának vannak nagyon jó oldalai és vannak kevésbé jó oldalai. Ez minden iskolára jellemző még egy konfesszionális [felekezeti] iskolára is. Nem minden tanár volt egyformán jó pedagógus. Nem mindegyik tanár tudott uralkodni indulatain. De az iskola egészben véve nagyon civilizált, haladó szellemű iskola volt. A tanárok között voltak igen kiválóak, akik nemcsak mint középiskolai tanárok tűntek ki, hanem tudományos téren is. Különösen kiemelem Dr. Déznai Viktor nevét, aki nekünk franciát tanított. Kiválóan tanította a nyelvet és a francia művelődést, a francia irodalmat: „Csukjátok be a könyvet, ami a könyvben van azt az érettségire kell tudjátok, most beszélek a francia irodalomról a francia műveltségről.” Igen sokat segített és művelődési távlatot nyitott előttünk. Ő különben urbanisztikával foglalkozott, városrendezéssel. Írt cikkeket, amelyek Temesváron jelentek meg, de voltak olyan munkái, amit Párizsban a Sorbon adott ki. Szóval urbanisztikai téren egy Európában ismert szakember, tudós volt. Nagy hálával gondolok rá, mert nagyon sokat tanultam tőle. Haza is jártam hozzá és olykor-olykor én rajzoltam az urbanisztikai térképeit, az ő utasításai szerint. Kaptam tőle könyveket kölcsön, úgy hogy szerepe volt a művelődési életem, a kultúrám kialakulásában. Nagyon szerettünk még az egészségtan tanárunkat, aki egy rendkívüli rokonszenves, nagyon ügyes orvos volt. Bennünket, fiatalokat, ő tanított meg sok mindenre, az élet intim dolgaira is.

Nagyon szerettem a természetrajzot, a számtanhoz nem volt semmi érzékem. A számtan, a geometria gyengéim voltak. Nagyon szerettem a történelemtudományt, és az érdeklődésem megmaradt mind a mai napig. Az idegen nyelvek közül a francia mellett még németet és ivritet tanítottak. Gyakran vittek bennünket a temesvári múzeumba, amelyiknek volt egy festészeti művészeti osztálya is, és ezeket én nagyon szerettem. Emlékszem, hogy a múzeumi látogatásokról írásos dolgozatot kellett készítsünk és egy alkalommal az enyém volt a legjobb.

A zsidó líceumban a szegény tanulókat alapítvány támogatta, amelynek 1935 körül én voltam a vezetője.

Az iskola mellett kellett járnunk a zsinagógába, a neológba. Névsorolvasás volt. Aki nem ment el, azt azzal ijesztgették, hogy annak rosszabb jegyet adnak az iskolában. Nem szerettünk kényszerből templomba menni ez egy tény. Volt egy igen meleg szívű hittantanítónk, Vajda bácsinak hívták, keresztnevét nem tudom. Szerettük, mert jó érzésű, meleg érzésű ember volt. Tudott a gyerekekkel bánni, neki is voltak gyermekei. A felsőbb osztályokban egy Fleischer Lipót nevű talmudista tanított nekünk héber nyelvtant. Az olvasást már megtanultuk a kisebb osztályokban. Megtanultuk héberül pontozva olvasni és írni. Aztán bibliaolvasás is volt héberül, ez már bibliai héber. Cionizmusról és kivándorlásról nem volt szó az iskolában. Voltak tanárok, akik cionisták voltak, de az én tanáraim között, akik az én korosztályomat tanították nem voltak.

13 éves koromban kellett volna legyen a bar micvám, de nem volt hozzá kedvem. Aki otthon előkészített az egy elég primitív valaki volt, amolyan egyházfi, aki a kérdéseimre egyáltalán nem tudott válaszolni. Mondtam is az apámnak, egy olyan ember készít engem elő, aki a legegyszerűbb kérdéseimre is csak annyit tud válaszolni, hogy: „Ez így van, ezt így kell tudni, ezt így kell mondani”. De azért mégis 13 éves lettem: tartottunk otthon egy ünnepi ebédet. Ajándékba kaptam egy új ruhát és egy új cipőt. Meghívtam aznap délutánra az osztálytársaimat, akik el is jöttek. Szóval megünnepeltük a bar micvát a magunk módján, a szüleim nem ellenkeztek ez ellen. Nem voltak merevek vallási téren. Ez egyáltalán nem csökkentette tudatunkat, hogy zsidók vagyunk. Az a tény, hogy bennünket, a testvéreimmel zsidó elemibe és zsidó líceumba járattak, az már részben tudatosította bennünk zsidó voltunkat.

Temesváron jártunk színházba, moziba. Megnéztük a magyar és a román színház előadásait is. Az 1930-as években egy zsidó színtársulat vendégszerepelt Temesváron. A színtársulattal lépett fel egy híres énekesnő is, Sidi Thal. A két világháború között Sidi Thal zsidó énekesnő, a csernovici jiddis színház társulatával együtt, több alkalommal is turnézott Erdélyben Az előadás alatt a vasgárdisták 7 pokolgépet robbantottak, aminek következtében többen meghaltak és megsebesültek. Az eset valószínűleg 1935-ben történt, az Új Kelet két világháború közötti kolozsvári zsidó napilap szerint. – A szerk. Én nem voltam ott ezen az előadáson, csak hallomásból ismerem az esetet. Ott volt viszont a jövendőbeli apósom, de nem sérült meg.

A zsidó fiatalság körében voltak konzervatív gondolkodásúak, haladó gondolkodásúak, baloldaliak, cionisták. Ilyen szempontból elég vegyes volt a baráti társaságom, különböző meggyőződésűek voltak a tagjai. Én nem vettem részt semmilyen mozgalomban, de rokonszenveztem a baloldali irányzatú Hasomer Hacair 8 szervezettel. Elmentem a rendezvényekre, előadásaikra, táncmulatságaikra, de nem lettem tagja. Temesváron volt egy zsidó sportegyesület a Kadima, ahova nem csak iskolások, vagy egyetemisták, hanem a dolgozó fiatalok is jártak. Részt vettem a Kadima újévi összejövetelein, amelyeken mindig ott volt a temesvári zsidó fiatalság krémje. Ezen kívül, nyár folyamán rengeteg közös kirándulást szervezett a sportegyesület. Szinte minden hét végén mentünk kirándulni. Gyalogtúrákra mentünk a közeli helyekre.

Az érettségim nem sikerült elsőre. 1936 őszén érettségiztem le. Latinból, román nyelv- és irodalomból, természettudományból és talán franciából kellett vizsgáznom. Régi elhatározásom volt, hogy orvos legyek. Apám anyagi helyzete megengedte, hogy külföldre menjek tanulni. Román egyetemekre akkor elég nehéz volt bejutni a numerus clausus 9 miatt, ezért elkerülendő egy esetleges sikertelenséget, ami évvesztést jelentett volna, 1936-ban úgy határoztuk el közösen, hogy Olaszországba megyek tanulni, Bolognába, a híres bolognai egyetemre. Ott volt két gyermekkori barátom is, akik már előttem kimentek Bolognába. Csatlakoztam hozzájuk és folytattam tanulmányaimat és baráti kapcsolataimat. Nagyon sok erdélyi magyar és román diák tanult ott.

Bolognában minden egyetemi évet ünnepség keretében nyitottak meg. Az ünnepséget az egyetem nagytermében, az Aula Magnában tartották a diákság és a tanári kar részvételével. A terem egyik végében ültek a tanárok, a dékánok, a dékán helyettesek. Talárban voltak mindannyian, arany nyaklánccal a nyakukban és az egyetemi bullával a kezükben. Baloldalt voltak a középkori ruhákba öltözött heroldok, karzaton pedig ugyancsak középkori ruhába öltözött trombitások, kürtösök. Négy kürtös állt, a kürtökön az egyetem zászlajával. Kinyíltak az Aula Magnának az ajtói és bejött a rektor. Hermelin köpeny volt rajta. Utána jöttek a heroldok és hozták az egyetem szimbólumait: az egyetem nagy középkori pecsétjét, bársony párnán. Ez után mindenki elhelyezkedett. A rektor felment a terem közepén levő szószékre és egy rövid beszédet tartott, ezzel nyitva meg az évet. Hát persze, ez nagyon nagy hatással volt ránk, felejthetetlen pillanat volt.

Tudom, hogy létezett Kolozsváron az Erdélyi Zsidó Diáksegélyző, amely kantint is fenntartott és támogatta a külföldön tanuló zsidó diákokat. Bolognában én csak a szülői támogatásból éltem, nem kaptam semmiféle segítséget ettől a szervezettől. Anyagi szempontból előnyős körülmények között lehetett tanulni Olaszországban és zsidó voltom miatt sem ért semmilyen megkülönböztetés.

Olaszországban csak két évet végeztem, 1936 és 1938 között, aztán haza jöttem Kolozsvárra és itt folytattam orvosi tanulmányaimat. Apám hívására jöttem haza. Ő úgy ítélte meg az európai helyzetet, hogy már háborús veszély van és jobb, ha a család együtt van. Az egyetemi évek Kolozsváron nem voltak csendesek. Mikor a vasgárdista mozgalom felvirágzott, az egyetemeket is megfertőzte. Állandóak voltak a zsidóverések. A zsidó diákokat megverték, a lányokkal nagyon „udvariasak” voltak, azokat csak hátba vágták. Emlékszem, hogy egy alkalommal egy sötét folyóson hagytuk el a tantermet, a fal mellett pedig, mindkét oldalon román diákok álltak, s a kijövő zsidó diákokat az egyik oldalról a másikra pofozták, köztük engem is. Ez 1939 vagy 1940-ben volt. Kolozsváron is csak rövid ideig tudtam tanulni. A második bécsi döntés 10 és Észak-Erdély Magyarországhoz való kerülése után érvénybe léptek a zsidótörvények, amik korlátozták a zsidók felsőoktatásban való részvételét. A numerus clausus 11 miatt félbe kellett szakítanom orvosi tanulmányaimat. Amúgy is, a családom Temesváron élt, ami a bécsi döntés után Románia területén maradt és így kénytelen voltam elhagyni Kolozsvárt és haza költözni.

A második bécsi döntéskor tehetetlennek éreztük magunkat. A családomat közvetlenül nem érintették az események, mert Temesváron éltünk, a Marosvásárhelyen és Kolozsváron élő rokonságunkat viszont igen. Tudtuk, milyen sorsa volt a magyarországi zsidóságnak a két világháború között, ezért különösképpen nem örültünk a bécsi döntésnek.

Ami a magyarországi deportálásokat illeti, nagyon sokan úgy tudják helytelenül, hogy csak 1944-ben kezdődtek meg deportálások, amilyen mértékben a németek megszállták Magyarországot. Hát a valóság az, hogy már 1944 előtt is voltak deportálások. Például az egyik ilyen deportálás a 40-es évek elején történt, még a német megszállás előtt. Összeszedték a környező országokból Magyarországra menekült rendezetlen állampolgárságú zsidókat és Galíciába vitték, ami akkor már német ellenőrzés alatt volt. Galíciában 10-12 ezer zsidót végeztek ki. Sámuel a kamenyec-podolszki vérengzésre gondol, ahol 1941-ben körülbelül 16-18000 magyar zsidót mészároltak le SS-egységek és ukrán segéderők. A magyar csapatok részvétele a mészárlásban nem tisztázott.

1940-ben már Romániában is igen szigorú zsidóellenes intézkedések voltak érvényben. Be kellett adni a rádiót, lefoglalták az autókat, bicikliket, kisajátították a zsidók házait. 1940-ben meghalt apám. Bátyáim már önállóak voltak, ők tartották el a továbbiakban az édesanyánkat. A háború után a temesvári lakásunkat az állami betegsegélyző épületéhez csatolták. Anyámat elköltöztették és kapott a várostól egy szobát konyha használattal. Ott halt meg szegény, súlyosan betegen, rákban, 1957-ben. A szüleimet zsidó szertartások szerint temették el Temesváron. Mondtak kádist is. Jahrzeitot nem állítottak össze róluk. Egyedül a nagyanyám Jahrzeitja volt meg, amit elküldtem az izraeli Cfátba, a Magyar Nyelvterületekről Származó Zsidóság Emlékmúzeumába.

Nemcsak Magyarországon, hanem Romániában is vitték a zsidókat munkaszolgálatra. Engem 1941 augusztusában vittek el. Ezek a munkaterületek az ország különböző részein helyezkedtek el. Először a Bánságban voltunk munkaszolgálaton, ahol kubikus munkát végeztünk, aztán áthelyeztek az Olt völgyébe. A leghosszabb időt Dél-Moldvában, Focsanitól nem messze töltöttem. A temesvári és aradi zsidók nagy részét ide hozták munkaszolgálatra. Focsani mellett egy ideig szanitécként dolgoztam. A munkaszolgálaton volt nálam egy szanitéc táska, amit még Temesvárról hoztam magammal, benne orvosságokkal és kötszerekkel. Idősebb korú embereket különösen gyakran kezeltem. Injekcióztam őket és még az is elő fordult, hogy a román katonákat is, ha megsérültek, én részesítettem elsősegélyben. Sőt a parancsnokunkat, aki egy kapitány volt, egy alkalommal szemfertőzés támadta meg a por és a rossz higiéniai viszonyok miatt. Én kezeltem ki, másodéves orvostanhallgatói tudásommal és a könyvek segítségével, amik nálam voltak. Sebészet és fertőző betegségek tankönyvei voltak velem. Előfordult az, hogy valakinek volt valamilyen furunkulusa vagy tályogja, én azt kikezeltem. A tályogot felvágtam, kitisztítottam, fertőtlenítettem az előírás szerint. Én inkább a kis sebészet terén tudtam segíteni, mert belgyógyászati ismereteim még nem voltak. Odáig nem jutottam el az egyetemi tanulmányaimmal. Ott, ahol én voltam, viszonylag normális körülmények között éltünk, de nem minden munkaszolgálatos egységnél volt ez így. A bátyám panaszaiból és elbeszéléseiből tudom, hogy, milyen szörnyű volt a pankotai munkaszolgálatosok helyzete. Pankota 40 kilométerre van Aradtól, északkeleti irányban.

Mi katonai keretben voltunk. Rádiót hallgathatunk, a mellettünk levő katonai egységek tisztjei pedig francia-, nyugatbarátok voltak. Volt köztük például olyan, hogy eljött hozzánk és tájékoztatott minket a háború állásáról. Az utolsó hetekben odajött az egyik tiszt és elmondta, hogy a visszavonuló németek a közelünkben vannak. Úgy gondolta, helyesen, hogy a visszavonuló németek talán megtalálnak bennünket és kivégeznek minket, munkaszolgálatosokat. Azt mondta, hogy: ’Adok nektek szekereket, hogy vigyen be benneteket a városba, Brailába, ahol még is nagyobb a biztonság, mint kint vidéken’. De erre nem került sor, mert 1944 augusztus 23-án a hadsereg átállt a Szövetségesek oldalára, mi pedig visszavonultunk a katonákkal együtt Braila felé. Nem vagyok egészen biztos benne, hogy előbb Focsaniba vagy Brailába mentünk-e, de emlékszem, hogy útközben találkoztunk fejvesztve visszavonuló németekkel, akik fegyvereiket eldobálva menekültek az oroszok elől. Brailán segélyt kaptunk a hitközségtől és mindaddig ott ültünk, amíg megindultak a vonatok.

Brailáról Bukarestbe mentem az ott élő rokonaimhoz. Felkerestem őket, fürödtem, tisztálkodtam náluk, ruhát adtak. A bukaresti hitközség is nyújtott pénzbeli támogatást. Én a kantinba nem mentem el, mert a rokonaimnál ehetem. Kivártam, amíg jelezték hivatalosan, hogy a vasutat helyreállították és lehet Temesvárra utazni. 1944 őszén hazautaztam. Otthon mindenkit épségben találtam: lánytestvéreimet, bátyáimat, anyámat. A háború után mindegyikük saját maga alakította az életét, amiről úgy érzem nincs jogom helyettük beszélni.

1944 őszén ismét beiratkoztam a kolozsvári egyetem orvosi fakultására, ami akkor Szebenben működött, ugyanis Észak-Erdély 1940-es Magyarországhoz való csatolásakor Szebenbe menekült az intézmény. Szebenben egy egyetemi évet végeztem, majd az egyetem Kolozsvárra való visszaköltözésével, 1945-től Kolozsváron folytattam a tanulmányaimat. Bele kellett szokjak ismét az egyetemi életbe és a román szaknyelvet is el kellett sajátítsam, mert én az alapokat olaszul tudtam. Előadásokra, gyakorlatra, laboratóriumokba kellett járni. A kolozsvári egyetem esztétika tanára Rusu professzor volt. Ragyogóan adta elő a zenekultúrát. Előadásaira minden fakultásról jártak diákok. Igen nagy műveltségű ember volt. Ismertette a műveket magnetofonról s az után a következő alkalommal, magyarázat nélkül hallgattuk meg ugyanazon műveket. Ez így ment végig, egy egész tanéven keresztül. Nagyon sok zsidó diák vett részt az előadásain, legalábbis az orvosi fakultásról.

Igen gyakran jártunk szimfonikus koncertekre. Más szórakozásunk a mozizás és a színház volt. Ősszel és tavasszal rengeteget kirándultunk a Kolozsvár közeli erdőkbe. A második világháború után volt Kolozsváron egy nagyon komoly zsidó diákegyesület, amely menzát tartott fent. Antal Márk [12 Diáksegély volt a neve. Ebéd és vacsora is volt. Rendkívül nagy segítséget jelentett, hiszen a háború után éhség volt. Nehezen lehetett élelmiszerhez jutni. Ennek a diákszervezetnek egy több diákból álló vezetősége volt. Pontosan a nevüket sem tudnám ma megmondani. Egyikre emlékszem, mert orvos lett: Antal doktor volt az egyik vezető. Időnként a vezetőségbe beválasztottak újabb tagokat is, például a vezetőségnek 1945-1948 között én is tagja voltam. Tagja voltam a kommunista diákszervezetnek is. A Pártba 1945-ben léptem be. Mint sokan mások a nemzetiségiek közül, én is azt reméltem, nem lesz többé antiszemitizmus, nemzetiségi megkülönböztetés, tolerancia lesz.

Voltak olyan világnézeti problémák, amelyekkel nem értettem egyet tudományos szempontból. Baloldalon nagyon hangoztatták a történelmi materializmus univerzális értékű jelentőségét. Hogy azok, akik elsajátítják a történelmi materializmust 13, azokat ez nagymértékben elősegíti a tudományos kutatás terén. Hamarosan észrevettem, rájöttem, hogy ennek nincsen alapja. Mert, a második világháború után, sőt már az első világháború után szinte kizárólag minden nagyobb jelentőségű orvosi felfedezés vagy találmány Nyugaton valósult meg és nem Oroszországban.

Szebenben ismerkedtem meg Valeriu Lucian Bologa professzorral, az européer gondolkodású kiváló tudóssal. Szívesen jártam az orvostörténeti előadásaira. Különben kötelező volt az óralátogatás, de nekem ez tetszet, szeretem a történelmet. Szorosabb kapcsolatba kerültem a professzorral és miután befejeztem Szebenben a tanulmányaimat megkérdezett, hogy tudnék-e Kolozsváron az orvostörténeti tanszéken dolgozni. Mondtam neki, hogy én különösképpen nem tudom, mi az, az orvostörténet. Az egyetemen túl keveset tanítottak ezekről. „Tudod mit, adok neked orvostörténeti munkákat, olvasd el és majd gyere mondd el nekem hogy szeretnéd-e csinálni, hajlandó vagy-e vagy sem.” Tényleg, egy hónap múlva, átolvasva a munkákat, megjelentem nála és azt mondtam neki, hogy tetszik ez az orvostörténet, szívesen dolgoznék a tanszéken. „De volna egy nehézség”, mondtam én. „Mi az?” – Kérdezte. „Tanár úr, én zsidó vagyok. Hátha ez gátolna engem a jövőben.” Azt mondta: „Édes fiam, engem nem érdekel, hogy milyen nemzetiségű vagy, az a fontos hogy szeresd azt, amit csinálsz és légy korrekt, becsületes.” Így 1945 őszétől kezdve egészen a professzor haláláig, vagyis az én későbbi nyugdíjazásomig, 1981-ig, az orvostörténeti katedrán dolgoztam Kolozsváron. Valeriu Lucian Bologa professzor tanítványa és utóda vagyok. Folytattam a professzor orvostörténeti előadását az egyetemen, mint hivatalosan kinevezet orvostörténeti professzor.

A gyakorló orvosi tevékenységet feladtam. Amilyen mértékben átadtam magamat az orvostörténeti tevékenységnek, olyan mértékben hagytam fel a gyakorlattal. Valami kevés gyakorlatot folytattam, de csak kizárólag a családon belül. Az erdélyi és a regáti orvostörténelemmel is foglalkoztam. Írtam és közöltem több könyvet románul, amelyekben ismertettem az erdélyi magyar orvosi hagyományt, személyiségeket. Azért románul, hogy a román orvos közönség ismerje meg az erdélyi magyar kultúrának ezt a szeletét. Első lépésem az volt, amiben a mesterem Valeriu Lucian Bologa professzor segített, hogy lépésről lépésre megismertem az anyagot, a romániai és az erdélyi valamint az európai orvostudományi hagyományokat és ezeknek a történelmi kialakulását. Meg kellett ismerni az orvosi eljárásokat és a népi gyógyászatot is. Lassan, lassan bedolgoztam magam a hazai orvostörténelem különböző alkotóinak a tudományos tevékenységébe. Különösen az európai orvostudomány erdélyi és romániai hatását vizsgáltam. Erre szükség volt és ezután lassan, lassan össze tudtam szedni gondolataimat, forrásaim gazdagodtak és kezdtem ismereteimet írásba foglalni. 1945-től kezdtem dolgozni a tanszéken, de az első könyvem csak 1954-ben jelent meg. Ekkor már sok anyagot ismertem, dolgoztam fel. Ezeknek az alapján jelent meg 1954-ben a gyűjteményes kötetem, amit a Román Akadémia adott ki.

Amilyen mértékben a tudásom gazdagodott, azzal párhuzamosan az egyetemi beosztásom is fejlődött, gyakornoktól a tanársegédig, később pedig adjunktusig emelkedtem az egyetemi funkcióban. Mikor a professzorom valamilyen oknál fogva hiányzott, vagy el volt utazva, vagy beteg volt, én tartottam az előadást és a szemináriumokat. Hosszú évnek kellett eltelnie, amíg odáig fejlődtem, professzorom segítségével, támogatásával, hogy nagyobb, összefogó, szintetizáló munkákat is ki tudtunk adni a professzorommal együtt. 1955-ben jelent meg a hazai orvostudomány történetével foglalkozó munkánk, amiért mind a ketten, Bologa professzor és én, 1957-ben Állami díjat kaptunk.

Az orvostörténet mellett foglalkoztam gyógyszerészet történettel is. E téren volt egy megvalósításom, amit meg kell említsek. Az 1950-es években, tehát a gyógyszertárak államosítása 14 után, itt Kolozsváron létrehoztam a város egyik régi gyógyszertárában, a Hintz patikában a Gyógyszerészet Történeti Múzeumot. Természetesen itt fel lett annak értéke szerint használva a híres kolozsvári Orient Gyula-féle gyógyszerészeti történeti gyűjtemény is. Ehhez még hozzá kerültek azok a gyógyszerészet történeti értékek, amelyeket az államosított gyógyszertárakból gyűjtöttem be. Gyönyörű muzeális értékű gyógyszertári edények, felszerelések, festmények, gyönyörű barokk officina asztal. Életem egyik legfontosabb munkájának tekintem a múzeumot. Ezzel gazdagítottam Kolozsvár kulturális életét.

Miután a professzoromat 1962-ben nyugdíjazták, átvettem az előadások tartását. Bologa professzor számára élete végéig biztosítva volt a tanszékén dolgozószobája. Állandóan ott is volt, jött és dolgozott. Én minden esetre fontosnak tartottam, hogy a mesterem számára biztosítsam a nyugodt munka lehetőséget. Sohasem gondoltam arra, hogy az ő dolgozószobájába költözzek. Annál is inkább, mert volt nekem külön dolgozószobám.

1979-ben írtam egy négyszáz oldalas gyógyszerészet-történeti munkát. Ez a gyógyszerészet egyetemes története, különös tekintettel a hazai, tehát a romániai gyógyszerészet fejlődésére. Egyelőre eddig ez az egyetlen egyetemes gyógyszerészet történeti munka Romániában. Vannak részletmunkák és a hazai, a román orvos- illetve gyógyszerészet történettel foglalkozó nagyon értékes munkák, de az univerzális, egyetemes gyógyszerészet történetnek egyelőre ez az egyetlen román nyelvű kötete.

1945-ben megnősültem, feleségül vettem Ungár Sárit, aki 1916-ban született. A feleségem zsidó értelmiségi családból származik. Gyermekkorát Szilágysomlyón és Nagyváradon töltötte. Tisztviselőnőként dolgozott. Temesváron ismerkedtünk és ott is házasodtunk meg. Csak polgári esküvőnk volt. Nagyon szegények voltunk, nem rendeztünk ünnepséget utána. Talán a családban volt ebéd, amin kizárólag a feleségem családja vett részt és édesanyám.

Kolozsvárra költöztünk, mert én akkor még diák voltam és kellett folytassam az egyetemi tanulmányaimat. Mind a ketten élveztük az Antal Márk Diákszervezet, diákotthon támogatását. A város szélén laktunk egy nagyon szerény pincelakásban. Azután, az 1940-es évek végén, a Jókai utcába [a város főterére nyíló utcába] költöztünk, a mai lakásunkba. Ideköltözésünkkor viszont csak egyetlen szoba volt a mienk a négyszobás lakásból, amelyen velünk együtt három család osztozott. Örökösek voltak a súrlódások a fürdőszoba használat és a konyha használat miatt. Vagy 5-6 évig folyt ez az együtt lakás. Miután megszülettek a gyermekeink, kértük a lakáshivataltól, hogy utalják ki számunkra a lakás többi szobáját is. Nem ment egyszerűen, csak fokozatosan kerültek a mi használatunkba a szobák, sok veszekedéssel.

Izsák György fiam 1950-ben született, két év múlva, 1952-ben pedig világra jött második fiam, Izsák András. A gyerekek felnőttek, innen mentek elemi iskolába, gimnáziumba. A középiskolát románul végezték. Anyanyelvük természetesen magyar, magyar könyveket olvastak gyermekkorukban. Nem titkoltuk előttük származásukat, zsidó tudatra neveltük őket. Mind a ketten az orvosi egyetemet végezték el Kolozsváron. György a sztomatológiára járt, Andris az általános orvosira. Andris 1978-ban fejezte be az egyetemet. Körülbelül negyed éves egyetemista korukban, úgy Gyuri, mint Andris is útlevelet kaptak és Nyugat-Európába utaztak. Párizsban élt egy orvos unokabátyám és az támogatta őket. Franciaországból átmentek Olaszországba, ott is voltak kollégáim, aki segítettek nekik, s így megismerhették a nyugat európai kultúrát. Itt nősültek meg, majd kimentek Izraelbe. Gyuri 1980-ban, Andris pedig 1981-ben vándorolt ki. Nem voltak cionisták, nem neveltük őket annak. Mi a diaszpóra hívei voltunk, de ők szabadabban akartak élni. Azt akarták, hogy utazhassanak, munkájukat élvezhessék. Most mind a ketten, családjukkal együtt Haifában élnek. Hetente beszélünk telefonon egymással.

1959-ben Jugoszláviában, Dubrovnikban részt vettem egy nemzetközi gyógyszerészet-történeti konferencián. A résztvevők között voltak jugoszláviai, dalmát zsidó gyógyszerészek. Meglátogattam a dubrovniki zsidó utcát. Volt egy szép barokk stílusú zsidó templom, azt is meglátogattam. Beszéltem ott egy hitközségi emberrel, aki egy őrféle volt, aki megmutatta nekünk a templomot. Spanyol származású volt, Toletónak hívták. A családja Toledóból érkezet. Az őr felnyitotta nekünk a Tóra-szekrényt és megmutatott egy régi, több száz éves Tórát, amelynek a fogóira az ő családjának a neve volt ráírva. Azt hozták magukkal Spanyolországból. Jártam egyébként Toledóban is, 1980-ban és meglátogattam a csodálatos szépségű toledói zsinagógákat. Alkalmam volt az évek során nemzetközi orvostörténeti és gyógyszerészet történeti kongresszusokon részt venni, egy-egy előadással. Néhány alkalommal a feleségemet is magammal vittem, többek között Csehországba, Franciaországba és Németországba. Nyugat-európai látogatásaink nem mindig a konferenciákhoz kapcsolódtak. Izraelben öt alkalommal jártunk, a fiainkat látogattuk meg.

A kommunizmus alatt Kolozsváron szamizdat irodalomhoz 15 nem nagyon jutottam hozzá, de nyugati rádiót állandóan hallgattam. Angol és izraeli rádiót hallgattam. Az 1989-es eseményekben 15 nem vettünk részt. Nem mentünk el a tüntetésekre.

A forradalom után sem változott meg a felfogásom zsidóságomról. Nem tartottam fontosnak, hogy a hitközségnek tagja legyek, sem a feleségem. De ez nem jelenti azt, hogy megszűntettük a kapcsolatunkat a zsidó hitközséggel. Igenis vannak kapcsolataink, többek között az, hogy amikor megtudtam, hogy a hitközség könyvtárat alapít, több ízben sok értékes könyvet adományoztam a zsidó hitközségnek. Legutóbb pedig felkért a zsidó hitközség, elnöke, Goldner Gábor, hogy írjak a kolozsvári, egykori zsidó kórház történetéről, amit meg is csináltam, át is adtam neki. Ezt magyar nyelven írtam, de most le lesz fordítva románra és valószínűleg angolra is, egy olyan kiadványban, amit a hitközség fog kiadni. Néhányszor ajándékként kaptunk a hitközségtől pászkát, és a munkám megírása után még azzal is megtiszteltek, hogy egy üveg izraeli konyakot küldtek. Tehát a kapcsolatok fennállnak.

A kolozsvári zsidó közösség esetében nem lehet újjáéledésről beszélni a szó igazi értelmében. A hitközségnek néhány száz tagja van. Pontosan nem tudom mennyi, talán 300 körül. Rabbi nincsen, valami előimádkozó van, aki ismeri szertartásokat és az imarendet. Létezik egy imaház és létezik egy zsinagóga a vasút felé vezető Horea úton. Az a deportáltak emlék zsinagógája. Azt a háború után hozták rendbe és helyezték el az emléktáblákat. Nagyobb ünnepekkor sem megyünk zsinagógába, mint ahogy 1989 előtt sem voltunk. Itthon sem üljük meg őket. Esetleg ünnepekkor fellapozom valamelyik zsidó történelmi munkát és elolvasom a rá vonatkozó részt.

Van egy kapcsolatom a Kártérítési Bizottsággal (Comisia Internationala a Revendicarilor de Asigurari in perioada Holocaustului), amely valahol Rotterdamban vagy hol van. Azzal én levelezésben állok, elküldtem az adataimat. Én nem voltam ugyan deportált, de voltam munkaszolgálatos. Románul leveleznek velem. Hosszú táblázatokat töltöttem ki, amelyeket ők nyílván tartanak. Évek óta levelezünk, de eredmény nincs semmi, azt sem mondták, hogy nem jár, és nem számíthatok semmiféle támogatásra, azt sem mondták, hogy jár.

1981 óta nyugdíjas vagyok, ma is tudományos tevékenységet folytatok. Több, tudományos társaságnak is a tagja, vagy tiszteletbeli tagja vagyok: a Román Orvostörténeti Társaságnak, a párizsi Nemzetközi Orvostörténeti Társulatnak, a Nemzetközi Gyógyszerészettörténeti Akadémiának, az olaszországi Orvostörténeti Társulatnak és a Magyar Orvostörténeti Társaságnak. Szabad időmben irodalmat, orvostörténeti munkákat olvasok. Nagyon élvezem a zenét, szeretem a zenei kultúrát.

Vannak magyar barátaim és vannak zsidó barátaim. Inkább több a magyar, mint a zsidó. Az orvos barátaim közül, hogy úgy mondjam szinte mindenki meghalt. Van néhány öreg barátom, akiket a hitközség tart el. Ezért cserében átírták a lakásukat a hitközségre. Az elmagányosodás érzése nehezedik ránk. Elmagányosodtunk, bár a fiaink minden héten felhívnak telefonon Izraelből és minden évben legalább egyszer hazalátogatnak.