Ferenc Deutsch

City: Budapest

Country: Hungary

Interviewer: Eszter Andor and Dora Sardi

- My family background

My paternal grandfather was Gabor Deutsch. He was born in Tiszaszollos in 1841, but I don’t know when he died. I didn’t know him. My grandmother was named Eszter Brunner. She was eighteen when she got married and my grandfather was twenty-one. We don’t know my father’s siblings, or even how many he had. The family was dispersed. My paternal grandparents lived in Tiszaszollos, but I don’t know what they did for a living.

My maternal grandfather was named Ferenc Kortner. His family lived in Szentistvand, a small village near Mezokovesd. They were pottery merchants. They did not own a shop but they went to fairs to trade. They had a horse and cart, which they loaded with merchandise and took to market. They went from fair to fair. They lived in difficult conditions.

My grandfather was an observant Jew and a prayer leader. He always had his head covered and wore a beard. My grandmother wore the sheytl (wig). There were fifteen Jewish families in Szentistvand and there was a strong Jewish feeling in that group. My mother grew up in this environment. The Kortners were a big family. About 80% of them never came back from Auschwitz. The grandparents died in 1919. Grandfather is buried in Szentistvand and we still visit his grave.

Our mother had ten siblings. They must have been born every second year. My mother was the eldest; she was born in Szentistvand around 1890. Her name was Gizella. Two twin boys came after her, uncle Bela and uncle Sandor. Uncle Bela was a cobbler and he had four children, though his wife died in childbirth. Uncle Sandor had four children too.

They came back from Auschwitz after the war and they went back to their house. However, later they had to run away, because there was a pogrom in Karcag. They ran away to Israel in 1947. Then there was aunt Szeren, who had four children with her husband, Uncle Bela Muller, a baker. He tried to give each of them a good trade.

The eldest son became a barber at aunt Szeren’s, the girl was a shoemaker, Pista was a merchant and there was one more son, called Feri, who was also a cobbler.

Then there was Jolan. She married once, gave birth to a girl, but then she divorced and could never remarry. She became a servant at the house of a school headmaster. Our family was very, very poor. Then there was uncle Jozsi, who lived in Mezokeresztes, and bought and sold animals.

There was also Aunt Margit, who lived in Szanto. I can’t remember any more. I had a close relationship with these relatives and knew them personally. Nearly the whole family lived in Putnok in the '20s because of my mother. My mother was the organiser, the one who gathered her siblings together in the village.

My father was born in Tiszaszollos in 1886. He worked in his father-in-law’s business. Then he worked in Diosgyor as a boilermaker. That was rare among the Jews, because most of them were farmers in Szentistvand too, but he had to go to Diosgyor to find work. My elder sister, Jolan, was born in Diosgyor in 1908; my eldest brother, Zoli, was born in 1910; and my other elder brother, Bela, in 1912. My father’s business was closed down in Diosgyor.

My father joined the army as a hussar in the First World War. There he met a lieutenant, who had a rented estate near Nyiregyhaza called Rakoczi Farm. The lieutenant was a Jew and he liked my father so much that he took him to the farm. So that’s how we got from Diosgyor to Rakoczi Farm. Corn and wheat were cultivated there and there was a distillery as well. There they produced the raw material for a factory too.

- Growing up

My father doled out the payment to the workers. He had a position between that of accountant and storekeeper. Those workers were summas, the lowest category of hired farm labourer. They were not given money for their work, but they were paid with products. It was seasonal employment. They worked during spring and summer, but there was no work during winter.

We lived on the farm, in a house made of mud bricks. It was a very poor house, but still we were glad to have a roof above our heads. I was born on the farm in 1917 and the landowner was my godfather. My Jewish name is Efrahim. I received this name, and my other name Ferenc, in honour of my grandfather.

There were ten families, and my mother managed to get one son in each of these families to take my grandfather's name. My little sister, Irenke, was born on the farm in 1919.

I was six when we moved to Putnok. There were roughly 380 Jewish families there. We Jews lived in one area, but there was a strong hierarchy between us. Because of my poverty I could never have married in Putnok. From this point of view, there was no great cohesion there. The poor were looked down on. Putnok was a very observant town, with a very orthodox Jewish community. It had a yeshiva, they educated bochers (students) in Putnok. There was a very observant rabbi there. He was bearded and had many children. He wore a caftan, and he had tzitzith on it.

We were educated to love the Jewish religion. My father was less religious than he was a hard physical labourer, but he kept the Sabbath. Our mother, however, was very religious: she did everything to ensure that her children felt Jewish. All the children were taught to read Hebrew and all had to have their Bar Mitzvah.

My mother read Hebrew but my father did not. Had my father been a bit more religious, my mother would have worn the sheitl (wig) too. I myself wore payot (sidelocks), but only until the age of ten. I had seen the other children wearing them and I did not want to be seen to be any less Jewish. Later, we wore the kipa at home. My younger brother is so religious even now that he goes to synagogue every day in the morning and evening.

We were considered very religious. My parents even took on a duty in the community. When someone in the town died, they would be washed – by my dear mother if it was a woman, by my father if it was a man. We were very kosher. I remember “taking the carving” (the gullet of the goose that has to be taken to the rabbi for him to check the kashruth). I remember that meat which had not been salted previously could not be placed on the table at all. We had to be very careful not to mix together the milk and the meat foods.

Every Thursday, my mother, and later my sister, bought a goose that we took to the shochet, as there was a kosher butcher there. When my sister opened up the goose, we were standing around the table to see the liver, hoping for it to be big, because then we could sell it. A doctor or lawyer would buy it and we could buy the next goose for the following week out of that money.

When my mother, and later my sister, opened the goose, they had the carving checked. When I took the goose to the rabbi for him to check, it was never treif (non-kosher). It might have happened that the rabbi thought – I presume now, according to my modern way of thinking – “It is Friday evening, and they have ten hungry mouths. If I say that the goose is treif the family is left without food. But if I pray for it, the family gets the food.”

When we had no goose, there was chicken. And then there was the Thursday lunch made of roasted fat with mashed potatoes. This was a tradition. On Friday there was meat soup. The family still keeps the tradition today. We call it the Friday tradition: meat soup, tarhonya (farfel) and garlic or tomato sauce. My mother lit a candle every Friday evening.

My father and the boys went to the synagogue, my mother and the girls stayed at home. We lived very close to the synagogue and just had to walk over. When we returned from the synagogue, then we had dinner. The whole family gathered at our place. There were at least twenty of us.

My dear mother wanted to show the hospitality of the house so she gave everybody corn on plates. That was hospitality. And then there was barhes (challah). My mother, and later my sister, made it.

On Saturday we had cholent. The children took it to the baker’s on Friday and it was ready on Saturday. As far as I can remember there were at least one hundred pots at the baker’s. They didn’t work at the bakery on Saturday because the owner was a Jew.

Bread and cakes were baked on Friday and after that the ovens were only used for baking the cholent. It was made in clay pots, it was tastier like that. We covered it and tied a piece of paper on the top on which our name was written. We had to be very careful not to mix up the pots. We only had beans and vegetables in our cholent.

Unfortunately, there was no meat in it, but when my mother or my sister felt like it, they put in kugel (flour dumplings) on the bottom. I remember that in the summer when there were gooseberries, we had gooseberry sauce. That was a real feast.

I used to be invited to a Jewish family’s place. My father was working in their vinegar factory. I had lunch every Saturday with them, because they had two sons with whom I was friends. The lunch began with an appetizer of eggs and goose fat, and then there was meat soup or cholent. In autumn it was meat soup, and in the summer, cholent. Then there was a roast, and after that, cake. We had fruit too, because they were wealthy Jews.

Nobody in the whole town worked on Saturday. At eight in the morning the prayers began and we were at the synagogue until noon. On Saturdays at noon, as the women descended from the balcony, I would take their prayerbooks, as it was forbidden for them to carry anything on Saturday.

I was allowed to do that until the age of 13, after which it was forbidden for me too. My father was never called up to the Torah, because when somebody was called they had to shnoder (offer money), and even had to buy a particular pasuch (verse of the weekly reading.) The shamash went around and offered the pasuch for sale. The poor could not afford it. Shnodering was necessary, because it supported the Jewish faith and education. The children had to be sent to school and money was needed for that.

On Saturdays, if we did not go to the synagogue for some reason, the children of the family got together. We had a prayerbook from which a certain part of the Torah had to be read for Saturday. We put on the talith or the tzitzith and then we imitated what we had seen the adults doing at the synagogue. We called each other up to the Torah; we said the mishe berach (blessing). This was sort of a game for us.

There were separate vessels for the Pesach, which we kept from one year to another.

There was a matzo factory and we could have matzo if the children went there to work. Then we got matzo for the eight days. We were glad when it got broken, because then it was not kosher anymore and we could take it home after work.

Later I would go to the manor at Pesach and supervised the milking of the cows. So I was in the position of meshgiach (ritual supervisor). I made people wash their hands, then milk cows into the pot I took for them. This was kosher milk. We took it by cart to the distribution centre and (people) got their Pesach milk from there. This was because at least at Pesach, people had to have kosher milk. I was there every time there was a kosher slaughtering.

I tried to learn the reiningen (cleansing). This means that from bovines, calves or any other ruminants, only the front part of the animal is supposed to be eaten. There, mostly in the thighs, are muscles from which the blood does not pour out easily. The reiningen is that the veins there must be cut with a knife. I wanted to learn this work because it was well paid. But I had no time and later no will to do so.

Yom Kippur was the biggest festival of all. I remember that our dear mother went to synagogue in her wedding gown. Though our father was not very religious, he still went to synagogue in kitl at Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. Even though we were poor, all the children got new clothes for the festivals.

At Succoth, all the children from the town gathered in the schoolyard and played with nuts. It went like this: we had about 10 or15 nuts and there was one called “the king.” The other nuts had to be thrown at it from a distance of about two metres. We all threw, and if you could hit the king, all the nuts we had thrown there were yours. But if you could hit only one, you got that one, and if that one hit another nut, you got both.

There was a big arbor, or Sukkuh, that was built for this holiday, and we ate under it.

Purim was more of a family get-together. At school we merely mentioned that Purim was coming and sometimes we had a performance to show where Purim comes from.

There were some villages close to Putnok where lived only a few Jews. Five or six of those villages would get together to have minyan (prayer quorum) at festivals. They would invite us to come from Putnok. I’d get lodging, food and a sum of money for them to have the minyan.

It was very important for every Jewish child in Putnok to attend Jewish school. There was a state school and there was the Jewish school besides that. From the first form untilthe fourth form we learned Hebrew in the mornings, and in the afternoons from two until four or five we learned Hungarian. We were given food at the school: every day we got a glass of milk and a croissant in the morning when school started.

We were taught the basics until the age of ten. The Hebrew letters were taught. They taught Rashi’s commentaries on the Talmud. Everybody had to learn Rashi at school. We had a female teacher named Lenke who taught Hungarian. She taught at the school for a long time, right up until the deportations.

There were about 20 or25 students per class, and until the fourth form we were mixed, boys and girls together. When we were ten the girls did not attend the religion classes, they stopped studying, but by then they had learned perfect reading and all the facets of Judaism.

Everything was around one yard: the synagogue, the rabbi (he was a great rabbi—we and others like us still visit his grave and put notes on it), the bochers, the Hungarian school, and the upper school, where the boys were taught mainly religion from the age of ten until fifteen.

At the upper school we read only Rashi and Talmud for five years, four hours a day. The teacher who taught religion from the fourth form onwards was named Wiess. From the age of ten or eleven we went to learn Gemarah (part of the Talmud, commentary to the Mishna) on Sundays. That also was taught by Mr. Wiess, but that cost money so nobody from our house could attend the Gemarah classes.

We prayed every day. Then the children who were already nine were taught to leinen (read the Torah). I left school when I was fifteen. We had to be attentive at school when we were praying. We did not say all the mincha (afternoon prayer) in one go, but we had to say it in parts. And the teacher would say: “Now, you go on.” And we had to be attentive and not interrupt the flow.

If we did not know where to read, we were punished. At each festival, we really studied the meaning. I had the honour to always say the brocha (blessing) at Hanukkah at the school. It might have been because of my voice or because the teacher liked me very much, as I was a diligent pupil.

Until the age of fourteen all the children had their tzitzith. We could not have gone to school without the tzitzith. More than that, Mr. Weiss, our religion teacher, checked the kashruth of the tzitziths to make sure they weren’t posl (faulty), not torn or worn out anywhere. Those of us who had no (financial) means, received tzitzith from the community. Those who had money gave contributions for it, because the Putnok community supported the synagogue, the cantor, the rabbi and the teachers. They paid for them.

All my brothers had the same schooling as myself, and my sisters too. All the children studied until the age of 14 or 15. I studied until I was fourteen.

My father was employed in Putnok by a Jew called Bernat Roth, who had a vinegar factory. The reason for his employment was that he had many children, and he had to do physical work. Later the vinegar damaged his stomach. We kept poultry in Putnok as we had a suitable yard, and my mother kept geese.

We had no vegetable garden but bought vegetables from the market. My mother was a housewife. I was already making money for my family at the age of six. When we got home from school, I would tie a small box full of candies to my chest and go from coffeehouse to coffeehouse selling them.

First we lived in a one-room flat, which had a kitchen. Later we lived in a two-room flat. Two more siblings were born: Pista in 1924 and Klarika in 1926. Klarika was eight months old when our mother died. My father was left with eight children and got so ill that he could hardly work anymore. My elder sister, Jolan, was nineteen when our mother died. She took over the seven children and raised us.

Jolan married in 1934. They were married under the chupah, but not in the synagogue. My sister insisted that she wanted her wedding in the open air. She also insisted that my brother-in-law wear kitl. He had kitl beneath and over it he wore an ibertzi - that’s a kind of overcoat.

Her husband was a second cousin, called Zoltan Grunwald, later Zoltan Galambos. He was a very, very good man. They lived on Marvany Street, in a huge house with a passageway. He worked as a painter-decorator there in that house, summer and winter. The inhabitants were always changing and whenever there was a new resident, a flat had to be redecorated.

A wealthy Jewish family wanted to adopt me, because they had no children, but my sister said that as long as she lived, no child would be given up for adoption. My sister couldn’t bear not having the children with her. She regarded us, her sisters and brothers, as her own children. My sister brought me to Ujpest in 1936. Juliska and my younger sisters, Irenke and Klarika and my father, came with me. In Ujpest we got a one-room flat with a kitchen at No. 23 Vaci Avenue.

I handed in an application to Koztisztviselok, which was a grocery store. like Csemege today. I was there for a one-month trial period. They wanted me until they asked for information and my religion had to be put on the questionnaire. Of course, I put “Jewish.” The next day I was out of a job.

This was between 1936 and ‘37. Then my sister got a job in the Pannonia Fur Factory as a fur cleaner. My younger sister got a job there too, and we made arrangements for my youngest sister to be trained to be a hairdresser.

I had an acquaintance who was the Member of Parliament for Putnok and he was an important man in the Parliament. I went to him in Veres Palne Street. He was a very good man. He gave me a letter of recommendation. That was the way for one to get a job at that time. I got into Wolfner Gyula & Partner leather factory, where I was hired as an unskilled worker.

This was a seasonal factory. I did hard physical labour, because we had to take leather sheets, which weighed more than one hundred kilos, to the processing section. I got an open hernia there in a few months' time. There was no work there during the winter so I was unemployed then and we lived on what my elder and younger sisters earned. With all that, we kept the festivals. It hurt me very deeply that we could not keep kashruth, but that was a financial matter then.

- During the war

In 1940 I joined the army as a regular soldier in Esztergom, and within a month I was taken as forced labour. I wore the regular uniform for a month, then it was taken away from me and I had to wear the yellow arm-band. People of my age group were taken to the Ukraine.

When the time came for me to be taken to the Ukraine, I was discharged because of my heart condition. And then I was recruited again. I was always being discharged and recruited, discharged and recruited. Whenever I was discharged I went back to the Wolfner factory.

In 1941 I got acquainted with a very cute little Jewish girl who was seventeen then. Her name was Irenke Klein and she was an only child. Her father sold pots at the Ujpest market. Her mother was very observant, her father less so. Their house kept kashruth. My wife was deported, but she never had chazer (pork) in her mouth. Our wedding was in 1941 in Ujpest, in the synagogue on Beniczky street.

I was considered an indispensable war-factory worker while working at the Wolfner factory, which is why I was not deported. We lived on the premises of the factory. There was a sort of bunker there and the workers were taken from there. They were all workers for the war-factory.

The soldiers used to come with their bayonets on and take them to work. I cooked for them, for about 300 people. The factory provided the ingredients and we had a very good company commander, who oversaw the cooking. We celebrated Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah in the bunker under his surveillance. He ordered the Torah to be brought for us to be able to celebrate our festivals as prescribed by our religion.

My pregnant wife was taken to Auschwitz with my mother-in-law in July 1944 and both were sent to the gas chamber. My father-in-law told me this when we met in 1945. When I found out that the ones from Ujpest were being taken away, I wanted to go with the family, so I jumped over the fence. I was caught and tried by military tribunal. One member was very kind; when I told him that my wife was pregnant and I wanted to join her, he was lenient.

I was taken to Sachsenhausen with the last transport in October 1944. In Sachsenhausen there was an international demonstration lager (camp) under the guidance of the Red Cross. There we were together with POWs. They were not taken for work as we were. We were together in the barracks and they got a monthly parcel from the International Red Cross.

They shared the contents of the parcels among the ten people in the barracks. Every morning at five we were taken in closed train cars from Sachsenhausen to Oragenburg, to an aeroplane factory which belonged to a company called Henkel. I was lucky, as I got into the engineers. I had to perforate plates, on what was called a vollmachine, but I had no clue about it.

In February 1945, when the Allied Forces were getting closer, we received an order that the lager at Sachsenhausen had to be emptied. We walked until Theresienstadt. We got to Theresienstadt at night on the first of May. Everybody was disinfected and we were given other clothes, which were fresh and clean.

For six days we were there doing nothing. I saw that we were in an area where families were together. They were all Czechs. They had flats where there were small children, and parents and grandparents too. I was amazed. More than once, the Germans were shooting as they left they and many died there in that lager.

I was liberated on the 8th of May, 1945. They wanted to take me from Theresienstadt to Sweden. All day long the loudspeaker said in all languages: “Don't go back to those countries which expelled you.” Very many went away, but I wanted to go home, because I did not know at the time what had happened to my wife, and I wanted to help the family.

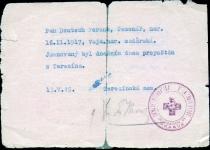

The International Red Cross had an office there where we were given papers, as we had no documents at all. The papers were filled in according to one’s declaration. Everybody stated their name, age and the trade they wanted. I declared at least three trades.

We were also given 800 Czech crowns. I stayed in Prague for some days on those 800 crowns to fortify myself a bit, then I left for Hungary. I got to Rakospalota in July, 1945. I went to the house we had lived in, but did not find anybody there. Then I went to the Bethlen Square, where I got a certificate stating that I’d been disinfected, and then I could get food and clothes.

Then I went to my sister’s place. Thank God, I found my sister and stayed with her for a week. They had been liberated in Godollo, where they were at the house of an acquaintance of theirs, hiding in the cellar. They had false papers. Her son Peter, who was six at the time, remembers that even though they were hiding all the time, my sister lit a candle every Friday evening, even there in the cellar.

My sisters Juliska, Irenke and Klarika never came back from Auschwitz. My brother Zoltan was taken together with his wife and three daughters. Our father was taken in the first transport directly to the gas chambers. My younger brother Pista hid in Budapest. My elder brother, Bela, got to Bor and was liberated in Buknikov. His wife and his six-year-old daughter did not come back from Auschwitz, nor did his mother-in-law.

- Post-war

Peter, Jolan’s son, was a very clever child. We wanted him to be an actor. As we wanted to send him to the Academy, he had an audition with the famous actor Zoltan Varkonyi. Varkonyi said that Peter had no talent whatsoever. At this, the child said: “Mother, I want to leave this country”.

In 1956 the family crossed the border into Austria. There the Jewish community asked them where would they like to go. My sister said that they wanted to go somewhere her son could learn to be an actor. They were sent to Syracuse, where the largest academy was. As they told it, a three room flat was waiting for them there, with a big refridgerator full of food, and a piano for the child to be able to practice.

My sister's liver ruptured in 1960 and she died. Peter met an American girl at the university who also wanted to become an actress. I managed to get to their wedding and I gave them our grandmother’s candelabra, which is 150 years old now, and has been passed from family to family. His wife lights candles in it on Fridays. He and his wife are very, very religious, but they are already living according to the modern religion.

Peter started directing on Broadway, but could not make a career for himself there. His father-in-law had a medical-instruments factory and said to him: “Come to the factory and learn this trade.” He learned it so well that from 50 employees the factory expanded to 200. Later they sold the factory and bought a smaller one. He now has two daughters and they are very well-off.

My younger brother, Pista, went to Israel in '56. Peter later brought him to New York He is also a painter-decorator. My elder brother, Bela, got to Rochester in '56. He went to work at the Kodak company. He met a Jewish woman, as his wife and child never returned from Auschwitz.

All three of us, my elder and younger brothers and I, live in the same town in America, Delray Beach.

For a year after the war I was the housekeeper for my sister’s family, as I love cooking. Then I got a position at the Fiume Stock Corporation. I administrated a coffee and teashop. I did well in the shop. I have skill in business in my blood. I inherited it from my grandfather, who was also a merchant. The leaders of the corporation liked me a lot.

At the end of 1946 I met my second wife. I would have liked to get married, but had no money. I went to my boss, Gyorgy Vajna, and told him that I wanted to get married and could buy a house for 25,000 forints in Pest. He said that it was a big sum. I told him that I could pay it back monthly from my wages, because I had good wages then. $10 or 10 kilos of sugar or 10 grams of gold was the agreement then, as the forint was good for nothing.

He said that the directors of the company would have a meeting later and they would discuss it. The next day the director told me to go back to the office the same evening, to lift the last page of the telephone book and there would be something for me. There was the 25,000. A month passed and I wanted to pay back part of the money, but the director said that I was such a good worker that I deserved that much and it was from the company.

I worked there until 1950-51. Then there was a problem again with my being Jewish. The company was taken into state ownership and I got a beautiful note from Vajna and a good recommendation. I handed in a CV to the Kozert, but I put in that I was a Jew, and they did not hire me. The next week I went there, handed in nothing, just made a fuss that I wanted to get in. They hired me to pack candies.

In three or four days' time I was already a leader. I was taken to Ferenczi Square to be a shop assistant. I was noticed and was taken to the headquarters. I was made supervisor with good wages, and later chief supervisor. One day I got a message to go to the director. Champagne was opened and I did not know what was going on. The next day I was summoned to the Ministry of Domestic Trade, and I got a position there. I was responsible for supplying bread to the whole country.

The Director at the Csemege Company, a Socialist food store chain, was a very good friend of mine.We had trudged through the mud together during the forced labour period. He asked me how much my wages were. I told him and he said that he would give me double that if I went to work for him. I moved to the Csemege Company in 1953 as a group leader, where I had to supervise all the shops in Budapest.

This job was not really good for me because I was a Jew and there was anti-Semitism. From there I got to the supplying section of the company. I worked there for thirty years. I managed to organise my work in such a way that I was the supplier for all the diplomats to Hungary from 176 countries.

Besides this I also oversaw fifty buffets. I supplied the diplomats with food in their private lives. If they needed some delicatessen, they could get it with my help. I got many high decorations, mostly from the government. This job had also some perks that raised my quality of life: Western connections, travels, food, etc.

I met my second wife on St. Nicholas’s Day at a dance party. First I thought that she was a Gypsy girl. Later I asked her what kind of church she went to. This was the basis of our friendship. She told me that she had no denomination, but she was a Jew and had been deported.

Her name was Sarolta Holstein. She had been born in Esztergom. Her parents had divorced, and her aunt and grandmother had taken her in and raised her. She was learning to be a hairdresser. She went to Auschwitz when she was nineteen together with her grandmother and aunt. Mengele sent the old lady to the gas chamber, the aunt to work and took my wife to the experiment lager.

The experiment subjects were in the experiment lager for six weeks. As my wife explained it, they were treated well, but when the experiment was over they were all taken to the gas chambers and killed so as not to leave any trace. Near Mengele worked a French Jewish doctor who had lost a daughter very like my wife.

The doctor told my wife that she had to leave the hospital during the night and take the transport the next day as Mengele would recognise her as one of the experiment subjects. They dressed her as a nurse and she was able to run away from the hospital and get to the barracks her aunt was in. There was a transport leaving for Horisov and my wife and her aunt made it there.

She and I got married in 1947 in the synagogue on Csaky Street. She was a hairdresser, but studied further. She graduated from college as a technical designer. She worked on the Nepstadion.

During our marriage she never spoke about Mengele experimenting on her. She could get pregnant, but not deliver.

In 1961 she received compensation because she had been an experiment subject. She was a star witness. A delegation came from Geneva, because I said that my wife had already been through great hardships and had had enough of Germany once. I insisted that if they wanted her to be a witness then they had to come here. And that's just how it happened.

The delegation came, she was called in, and they examined her. They concluded that everything my wife had said was true. We handed in the papers for the compensation here in Hungary. My wife was given 40,000 deutschmarks for having being used in the experiments. I said that this was blood money. My wife and I agreed that if we could not have a family, we would travel.

I had an agreement with the finance minister of the time, that I wanted money in deutschmarks. And so we went to other countries for my wife’s enjoyment. When she became ill, I retired before the required age.

She and I kept the festivals. We had the Jewish feeling, and never left the faith.

My elder brother changed his last name to Deak. At this, my younger brother Deri and I said: “Our father was burnt in Auschwitz, and he was burnt as Vilmos Deutsch. I remain Deutsch. I do not want to give up my name. I do not want to give up my Jewishness.”

On Yom Kippur I did not work at Csemege. The director had a secretary. She had been a nun and we agreed about religion. OnYom Kippur I was at the synagogue on Dohany Street. I left and phoned her to ask if there was anything unusual. To this Magdi said: “Feri, dear, just get back and pray in peace, there is nothing.” She covered me whenever I was at the synagogue at Yom Kippur or other festivals.

I was between life and death when there was war in Israel. I arrived in Israel at the most critical moment. I went to see my younger brother in Haifa during the Six-Day War. I was there only until the war started in earnest. A friend told me not to go. He had a position where he was well aware of the real political situation. I was in the Holy Land four times. Nearly each year I went to America to see my relatives, my brothers. And then later I went on official business too.

In 1981 my second wife died. Not much later the aunt who had raised her died too and I went to her funeral in Cleveland. I had quite a large circle of friends who supported me and wanted me to stay there. I had a very good friend who had a big restaurant and took me to his workplace, for me to forget and to get away from all. He looked after me for a month and suggested that I stay, but I did not feel like it. Together with my second wife’s aunt’s widower , I decided to go to Florida for the winter.

There I met a widow at a lunch. Her parents had emigrated in 1906. Her mother had been sixteen and her father twenty. Her father had graduated from school in Tokaj and Satoraljaujhely. He was very observant, and he was so intelligent that he spoke seven languages. Her mother was illiterate; she was from some village in the North.

The widow was my intimate friend at first for nine months. I asked her to visit me in Hungary and then I told her that I wanted to marry her. The family was well off enough to try to talk me out of it, but I told them that I was family-oriented and I wanted to marry her. We decided to get married here in Hungary.

This was in 1984. We divided our life in this way: I had a flat here in Hungary and we spent three months here, and nine months in America. She died in 1990.

I stayed alone after that for six years, not thinking of a fourth. But I came home and met my wife. Her name is Edit Czitrom. She was born in Budapest and is a teacher. Her mother was 91 when she died and she my wife was with her mother until the age of 58. She did not want to leave her. We have a flat here and another in America; I’ve got a car, and a very good wife. What more could I want?