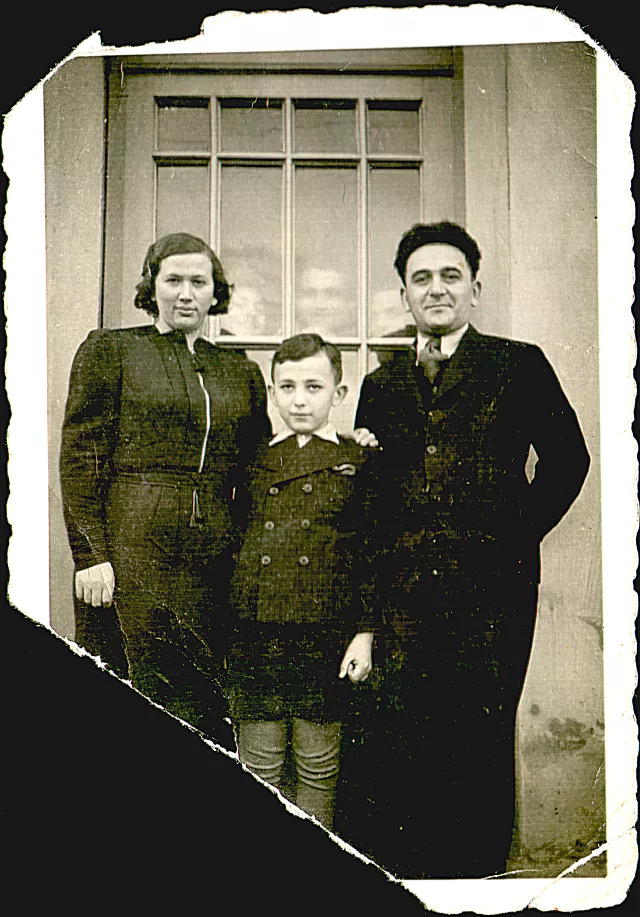

I am in the picture with my parents in Nagykanizsa, at the entrance of our bakery on Tavasz Street. The ones peeking behind the glass door are perhaps the employees of the bakery: the assistant, the apprentice and the servant. The picture was taken in 1939.

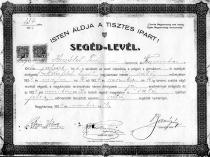

My father, Geza Leicht became a baker's man in the bakery of my maternal grandfather in 1923. But there was another assistant there who was called Terezia Herczfeld. She learned the baker's trade for 3 years in my grandfather's bakery in Nagykanizsa, and she graduated with distinction at the apprentice school in 1924. It wasn't usual for a woman at that time to have an assistant's certificate.

My parents worked in the bakery with an apprentice, a baker's man and a domestic servant at night. For a kilogram of bread, for the dough and the cleaning of the workshop 4 liters of water was needed. They carried the water from the yard, from the well, the domestic servant pulled up the 4 cubic meters of water from the well every day. When he didn't pull up water or carry water, then he cut wood for the oven. The domestic servant lived at our place, in the attic above the oven and ate at our place, too. The apprentice and the baker's man, too, everyone. Our last apprentice was Jewish, who was unfortunately killed in Auschwitz.

There were two ovens in the bakery. One was called lifting oven which lifted the dough and baked a little crust on it. Then they took it out, and in nice German baker's language they umpakk, put it in the other oven, which was called Umpakk-oven. The bread was baked in that. Then they switched. The umpakk became the lifting and the other one became the baking oven, several times a night. They called the tier stand where they put the baked bread garb. Everything had such a funny German name, for example there was something called pekedli, which was a half liter mug with water, with which they cooled the oven if it overheated. Because at that time there weren't instruments which could show the temperature of the oven. The baker had an instrument for that, a handful of flour. If he threw that in the hot, empty oven and the flour just fell and burned- it didn't burn in the air sparkling, or it didn't just fall and remain there, then the temperature of the oven was right. If it was too hot, they pored in a couple pekedli of water. And there was the streisechter, which was a cowl, in which there was water, and using a brush with a handle called vishli, the kind that looks like the back-brushes they sell today, they brushed the flour off the bread, so that the crust would be crunchy. I think nobody knows these names anymore.

When my parents finished their work in the morning 800 kilograms of bread was baked, and there were rolls, too. But they still couldn't go to bed, because then the baking of the dough prepared at home followed. The housewives kneaded the dough at home and took it to the bakery to have it baked. They brought it in bread-baskets put on their head. This cost 5 filler a kilogram. We weighed the baked bread, and we got as many times 5 filler as many kilograms it weighed. And a kilogram of bread cost 36 filler. I knew this very well. Nagykanizsa had 32000 inhabitants and 36 bakers. 800 people could support one bakery. And we had enough customers to get by well. My father was the best specialist in town, the best miser - this is also a German word, it means to stir or blender. He smelled the flour, looked at it, felt it, and told how much yeast, salt and water was needed. Many mills delivered flour, and each was of different quality. And the one who could tell how to make a good bread out of that, was the miser. And my father made excellent goods out of everything. The clerks, the movie theatre, the hospital, and almost all the restaurants bought the bread from us. And we supplied for the district, too

The house on Tavasz Street, in which we lived, wasn't ours, but my father rented it for 140 pengoes a month. This was a lot of money, 20 pengoes were a good day-wages, a loaf of bread cost 36 filler, an egg cost 4 filler. At that time the girls weren't with us anymore, because Vilma took the two small ones, and Ilona and Irma had got married by that time. On that housing estate for public servants 3 Jewish families lived: a baker family, that was ours, a grocer, and a very old Jew, Uncle Dukasz, who was a private citizen. But he couldn't have had much money, because he was a private citizen among miserable conditions. The other family was Istvan Burger, his wife and their daughter, Iren Burger, they were the grocers. The girl was my friend in my childhood and I adored her. Unfortunately she was killed in Birkenau.