Lora Benjamin Melamed

Sofia

Bulgaria

Interviewer: Patricia Nikolova

Date of interview: September 2004

Lora Beniamin Melamed is a considerate and kind person to talk to. Her delicacy and intelligence blend into a strong selflessness towards the interlocutor – a rare quality. Her appearance reminds of a beautiful fragile porcelain figure from the XIX century. Lora is a very affectionate, delicate and interesting woman.

My ancestors came to Spain more than five hundred years ago. [Expulsion of the Jews from Spain] 1 After the Jews were persecuted from Spain, a big part of them settled on the Balkan Peninsula. Some of the Jews were killed by the Inquisition and another part adopted Christianity, but most of them left Spain and moved to the Balkans. The Jews in Greece, Turkey, Macedonia, Bulgaria, a part of former Yugoslavia and a part of Romania spoke a Spanish language from the Middle Ages. It was called Ladino or ‘Spaniolit’ as Bulgarian Jews often call it. My ancestors are Sephardi Jews like most Jews in Bulgaria 2, although some of them are a mixture of Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews. So, my ancestor’s traditions and rites are Sephardi and they spoke Ladino.

My paternal and maternal grandparents were born in the beautiful Bulgarian town of Samokov. They were quiet and kind people with a great sense of humor. They dressed in cheap, but clean clothes. They did hard physical labor all day. They were religious, especially grandmother Orucha (the mother of my mother Iafa Beniamin Kohen), who was very lively and talkative. I knew from an early age that Grandma Orucha lost her husband early and that was why she constantly prayed to God to join him as soon as possible.

Grandma Orucha was something like a hakham for the family. She loved gathering all the families of her children on the high religious holidays. She did all the preparations by herself and she also found some free time for us – her grandchildren. I still remember how she taught us a game with walnuts and what songs to sing on the various holidays. She had interesting conversations with the adults and the children. And she had a lovely sense of humor. She could tell us a lot of interesting, important or funny stories. She dressed in cheap, but very clean clothes. She did not stop working for one minute – cooking, cleaning, going to the synagogue where she always sang. She insisted that the families of her children observe both at home and in the synagogue the Jewish traditions on erev Sabbath and during the holidays.

I remember that my maternal grandfather Rahamim Yuda Levi wore simple, but clean suits and a hat, while my grandmother wore a kerchief. They were not educated. My maternal grandparents were not members of a party, although my grandfather adopted the communist ideas before 9th September 1944 3. That is, he believed in social justice and kindness to people regardless of their nationality or culture. About my paternal grandmother Mazal Shemtov Kohen and grandfather Nissim Shemtov Kohen I know only that he was a merchant and she was a housewife. They were both from Samokov, as was my mother’s family. They were both religious, observed kashrut on Pesach, fasted on [Yom] Kippur, celebrated erev Sabbath and all high religious holidays such as Rosh Hashanah, Chanukkah, Sukkot, Lag ba-Omer, Tu bi-Shevat, Simchat Torah.

We lived in a small house in Samokov. We were about 10 people: my parents with their four children, my maternal grandparents, uncle and aunt, and their children. Our house had two rooms and a kitchen. We did not have a bathroom. We did not have electricity, nor running water. We used an ordinary wood-burning stove to warm the house. We got water from the faucet outside, even in the winter. The faucet was quite far from our house. So, my parents decided to build a faucet in our yard. I remember that we, the children, helped a lot to make it. And we did not have to go so far away for water. Besides, my mother wanted us to grow up healthy and strong. She made us wash ourselves with cold water. They made us a special place in the house where we did gymnastic exercises.

We had a small garden, in which my mother sowed vegetables, fruit and flowers. We did not have any domestic animals, nor any maids. But our neighbors – the Bulgarians and the Jews were very kind people. We got along with them very well. They cheered with us if someone from our family managed to sell something in a nearby village, or went to have medical treatment at a bath, which was the practice at that time.

My mother's name is Iafa Beniamin Kohen, nee Levi, and my father's name – Beniamin Shemtov Kohen. They were both born and raised in Samokov. My mother had primary education and my father - secondary high school education. He knew French, because his parents wanted him to go to study in France, which did not happen, because my father was the first born child and his duty was to stay and support the family, who was not very well-off. My father believed in communist ideas, but I did not remember if he was a member of the party or if he was involved in illegal party activities. In this sense my father was more of an idealist and communist in beliefs than an active party member. My mother was apolitical.

My parents spoke in Ladino to each other. Of course, since we had to go to a Bulgarian school and when we were among Bulgarians, we spoke Bulgarian and learned Bulgarian very well. So, we spoke Ladino and Bulgarian equally well, though our Bulgarian vocabulary was richer. My parents did not know Ivrit, though they both were very religious, observed kashrut on Pesach, fasted on Kippur, celebrated erev Sabbath and all other high religious holidays such as Rosh Hashanah, Chanukkah, Sukkot, Lag ba-Omer, Tu bi-Shevat, Simchat Torah.

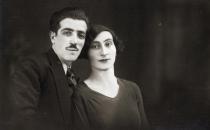

I do not know how my parents met. But I know for sure that their wedding took place in 1919, when my father was 37 years old and my mother – 29 years old. My parents' brothers and sisters were kind people. My parents kept in constant touch with them. They met on holidays, weddings, celebrated holidays together, visited the ill relatives. My father's sisters are Ester Beniamin Kohen [her maiden family name] and Victoria Beniamin Kohen, but I do not remember anything else about their families or about them. My mother's sister's name was Rashel Rahamim Levi [her maiden family name] and her brothers' names were Mordehay Rahamim Levi, Leon Rahamim Levi and Ruben Rahamim Levi. I have no information about them.

I remember that my father worked in a small shop owned by him, but did not earn much money. I also remember that we were constantly short of money and my father had to carry goods on his horse to the nearby villages on Sundays. He carried the villagers' hats, which my mother sowed and knitted at home, as well as cotton, or other things they needed. The Bulgarians bought them and provided us with an income. At first my mother sowed clothes for my father's shop. My father often worked as a travelling salesman to the nearby villages so that his children would have enough food and clothes. My parents also insisted that we further our education. When my parents wanted to go for a walk, they asked us to draw or write something interesting, made up a variety of artistic activities, then they came back and pointed out our best works.

There was not a Jewish school in Samokov. But there was a Bet Am [i.e. a Jewish home], where there was a Sunday school. A special teacher from Israel [then Palestine] was invited there and he taught us to read and speak in Ivrit. We learned a lot then, but we could not practice it anywhere so we soon forgot it. I remember that there was only one synagogue with one rabbi, who was also a chazzan. Unfortunately I do not remember his name. Since my father had the Kohen family name, he had to sing in the synagogue as a kohen. When he was not in the shop, he was in the synagogue. He loved singing and he had a great voice.

I was born on 11th November 1924 in Samokov. My sister and my brothers are Milka Beniamin Revah [nee Kohen], born in 1921, Sinto Beniamin Kohen [1923] and Miko Beniamin Kohen [1926]. We have always been best friends. The four of us were born in Samokov where we studied in the same school (there was no other high school). I remember that we all loved going to school and to the Sunday school. Besides, we always had a lot of books at home, on secular or religious topics. We, the children, loved reading aloud sitting together with our parents, which did not happen very often because my parents were very busy.

My sister Milka was the first to start learning to play the violin. She had private lessons, which also affected our family budget. In order to pay the teacher my mother prepared a large table cover, which she gave to her instead of money. My brother Sinto played a mouth the mouthorgan, and later – an accordion. My little brother Miko had inherited my father's talent and sang very well. I also played the violin when I was in high school. So, we made some merry concerts at home, in which everybody took part.

On the whole, our family was part of the Jewish community in the town of Samokov, which was not big. The high Jewish holidays such as [Yom] Kippur, Rosh Hashanah, Pesach, Purim, Sukkot, Lag ba-Omer, Tu bi-Shevat we always celebrated at home and at the synagogue. Of course, we had the best time when we celebrated them at home. Like all Jewish children, we also loved Purim most. It was most fun then. Usually our parents prepared some cheap things, because they did not have money to buy us expensive gifts. But every time my mother made some nice and colorful purses, in which we put sweets, candies and other sweet things. Then we made a contest who would remain with most sweets in their purse. And whoever won, was considered the most important child.

I studied philosophy in Sofia University ‘St Kliment Ohridski’ 4, but I did not graduate. When I was a student I helped my parents a lot. I went shopping with my mother who was always busy, I helped her in the sewing, cooking, cleaning. I also helped my father who had a hard time earning money from the shop and I sold instead of him the clothes sewn by my mother. Besides the miserable conditions we lived in, I also have other unpleasant memories. I was still a high school student, when I felt anti-Semitism for the first time. On some Bulgarian holiday lots of people gathered in the center of the town, folk music was playing and a beautiful folk ring dance was winding around the central square. We, the three Jewish girls who studied in the Bulgarian school, also joined the dance. Suddenly a tall student came, stood between us and with a strong hit accompanied with dirty and insulting words drove us out of the dance. The three of us also sang in the school choir. We sang patriotic, Bulgarian songs, which I liked very much. Soon after that incident our music teacher, whom I respected very much, summoned us and told us that a higher authority forbade us to sing in the choir. That happened before the Law for Protection of the Nation 5 was adopted in 1942 [Editor’s note: the law was promulgated in 1941].

We had a Jewish youth group in Samokov, we met often and had a great time. At first we gathered in the Sunday school, where we sang and studied Ivrit. My favorite song at that time was ‘Adio kerida’ [Goodbye darling]. We also tried to improvise short plays and theater performances, whose plots we made up by ourselves. My friends then were Stela, Bella, Panka and others (unfortunately I cannot remember their family names). When the Law for Protection of the Nation was adopted, our group disintegrated. We stayed at our homes in Samokov, but it was like living in a ghetto. We wore the shameful yellow stars, we were humiliated and had to observe a number of limitations, such as the curfew and the ban on Jews to go to social places such as theaters, cafeterias, shops and restaurants in front of which there were the degrading notices ‘Entrance Forbidden for Jews’ or ‘Sale for Jews only’.

In the worst time during the Law for Protection of the Nation, we, the young Jews, had a small Jewish orchestra, including a violin, accordion and other instruments. We gathered, sang and had fun. But suddenly, in 1943, my family learned that we would no longer live in Samokov, because we would have to be sent somewhere else, no one knew where. [Internment of Jews in Bulgaria] 6 At that time some of the interned Jews from Sofia had already been living in Samokov. We had to think about what to pack. Of course, the first thing I thought of was the violin. The rest of the orchestra also packed their instruments. We thought that we were sent to somewhere only temporarily, to some place like Samokov. Gradually my parents learned that something was not right, that things were not as we thought. I remember that my father’s Bulgarian friends supported us a lot, so did the people from the villages to which my father went and sold bread during the Law for Protection of the Nation. They would bring us a little butter, a little yogurt, a little bread. And they would tell us, ‘Don’t worry, we will help you, everything will be okay.’ In the end, they did not send us anywhere, although we never fully realized how nightmarish our journey would have been.

When the scary days came, other friends of my father’s, and some classmates of mine also came to console us, although we were afraid for our lives all the time. We were really very afraid. Germans walked around the town all the time, people shouted at us and threatened us with murder, that they would cleanse Bulgaria from the Jews and horrible things like that. The scariest thing was when a classmate of my sister’s tried to kill her once. She was returning home one evening, when he ran after her with a gun and tried to catch her and kill her. I remember very well how horrified she was when we came home. Then we realized that something very frightening awaited us. And our friends came secretly and told us, ‘We will stand beside you, we will not let those horrible people hurt you.’ The people consoling us were Bulgarians again.

From the articles that I read in the papers at that time (‘Utro’ [Morning] and ‘Zarya’ [Dawn]) I remember that the Law for Protection of the Nation was introduced after the fateful meeting between the monarch at that time King Boris III 7 and Hitler in November 1940 and with the signing of the Trilateral Pact by the Prime Minister Bogdan Filov in Vienna on 1st March 1941. Very few people know that in a strange concurrence of consequences the Hitler forces entered Bulgaria on 3rd March – 63 years after the Russian forces liberated us from Turkish rule 8. In fact, the meeting between Hitler and Boris III introduced a lot of the Nazi ideology and practice to Bulgaria.

In the days before and after the meeting between the king and Hitler in Bulgaria a very energetic anti-Semitic campaign was started, which my Jewish friends and I found very strange for our peaceful country. It was started by a number of Bulgarian pseudo scholars led by Filov and the Interior Minister Petar Gabrovski 9. To our surprise they were fascinated by the Nurnberg laws. And they openly declared that the Bulgarian, was of a pure Aryan type, which had nothing to do with the Slavs. And we, the Jews, were the main enemy of that so perfect Bulgarian. Those speeches supporting Hitler’s ideology led to a kind of a Kristallnacht in Bulgaria. Thanks God that I am not a witness, but we all knew from witness reports that groups of youths in uniforms armed with knives broke down the windows of the Jewish shops. And despite the resistance of the citizens, they stormed the poor Jewish neighborhood Konyovitsa, broke down flats, molested old people and women, painted swastikas on the walls, as well as anti-Jewish and anticommunist slogans.

I remember that all people from Sofia and the country were shocked. But then came a strange lull – no one commented on what happened, probably the people were afraid of the authorities, I do not know. Maybe thinking that the silence of the people was a kind of agreement, the Interior Minister suddenly declared that he was introducing to Parliament a bill called ‘Law for the Protection of the Nation’. We had no idea then that this law would be like the Nuremberg laws. In fact, the only difference between the two laws was that the Law for Protection of the Nation did not say anything about blood or blood differences, but about religion and religious differences. It would have been stupid and laughable if its creators had put in it terms like an ‘Aryan’ and ‘purity of the Aryan race’. But this small difference provided some Jews with the chance to adopt the Christian faith quickly. I do not know such Jews personally, but I have heard about them. My Jewish friends and I did not approve of their hasty act. But then the authorities noticed that omission in the law and hurried to add in a consequent regulation that relationships between Jews and people of Bulgarian origin are forbidden.

There were also some cases of superstitions related to Jews. For example, I remember that during the Law for Protection of the Nation a rumor was introduced that on the Jewish holiday of Pesach Jews would steal a child in order to imprison it in a barrel with nails, can you imagine that, and in this way they would drain its blood, which was necessary for the holiday…. I remember that there were some simple mothers who really believed in these things. And when Pesach approached they were very afraid about their children and told them to run if they see a Jew on the street, run, so that they would not be caught and their blood drained. I have even heard such a pseudo threat used by some women to scare their children when they did some mischief – threatening to leave the child to the Jews, to the ‘blood-drinkers’. There were also cases when a child would disappear and the first thought of those people would be that the Jews had stolen it to drink its blood. For me that was an obvious form of anti-Semitism, but thanks God, it was not very common in the Bulgarian society. I speak only of individual cases, but although they were rare, they did happen.

To be honest, I think that King Boris III carries a political responsibility and he was not the true savior of the Bulgarian Jews. The truth is that at those trouble times, we could really rely on our Bulgarian neighbors. The anti-Semites, with all their cruelty, were only a number of crazy individuals. I remember that both before and after 9th September 1944 opinions were heard throughout the country that the former king Boris III was a democratic monarch. Yet, I think that is not true as far as democracy is concerned, because at that time tens of thousands of people (including many Jews) were sent to prison in the name of ‘His Highness’ and underage girls and boys were executed in the name of ‘His Highness’ with his signature on their sentences.

All of us in Samokov were very happy about the big protest organized by the Jews in Sofia on 24th May 1943 10 against the internment of the Jews from Sofia and the deportation of all Bulgarian Jews. The protest started from the Jewish school, moved past the [Great] Synagogue 11, along Stamboliiski Blvd, where the Jewish Cultural Home [Bet Am] 12 is still located today, and stopped at the Klementina Square. Some of the protesters wanted to go to the palace and ask King Boris III, called by Hitler ‘the fox’ to help them. The Sofia Jews interned to Samokov told us that the police met them with trucks and wagons somewhere along Opalchenska Str. between Stamboliiski Blvd and Vazrazhdane Square. They arrested a lot of the protesting Jews, led by rabbi Daniel 13. It was good that he managed to hide at the place of bishop Stefan [Exarch Stefan] 14, who remained in history as one of the greatest supporters of the Jews in Bulgaria. His protests against the deportation of our Jews played a major role and are still remembered with gratitude by the community.

But in the end of 1943 Italy had already left the war by breaking the alliance with the Germans. The Americans and the English had entered Italy. They started bombing Bulgaria from Italy but not so intensely as Romania, for example. The situation changed fast and contrary to the expectations of the Bulgarian government after October 1943 the Americans started bombing Sofia for real. The reason was that their way to Romania passed through Bulgaria, that was why they bombed Sofia and some other towns. In Samokov we only heard about the bombings, but it was more than enough to increase the fear, which we felt all the time.

My hometown Samokov like most of the big towns in the countryside accommodated a part of the interned Sofia Jews during the Law for Protection of the Nation. I think that introduced some optimistic vigor in us, the young Jews from the country, despite the tragic times. We often gathered together, discussed our situation and always tried to view things from a positive angle. We organized progressively oriented groups (an illegal youth party organization). All the time Jewish chamber orchestras were being formed, in which the accordionists were the center of the company. We read a lot. We exchanged the so-called ‘progressive’ books (books by Gorky, Lenin, Marx etc.) which we were eager to discuss. I found that fascinating! When radio sets were officially banned, we gathered in a small ‘bozadjiinitsa’ [a shop selling boza] 15 on the market street, in which the radio was always on.

It was a great pleasure for us, the Jewish youth, to spend the Sunday mornings there, drinking boza and listening in a daze to the traditional holiday concerts. I do not know if even real musicians could be so impressed by the overture ‘Koriolan’ or ‘year 812’, ‘9th Symphony’ or ‘Pathetic’, Beethoven and Chaikovsky… We would gather around a small table and listen in a trance, lost in a world, which was unreal, and yet belonging only to us, a world, which lifted us above the horrifying present. What we heard, filled us with revolutionary emotions, we were ready to fight so that there would be ‘An Ode to Joy’ for everyone in the world.

The exultation at our unreal world continued until the fateful day. The rumor spread with the speed of lightning: we are going to be interned. Where? Why? Nobody knew. Our parents felt the enormous danger, but tried to save us the worry. The appointed day was coming close with all its terror. Still optimistic, we, the young Jews, went to farewell meetings with our favorite friends, promised that we would write to each other from the new place… At home we packed violins and accordions, my mother cried all the time, while my father, seemingly angry, scolded her. And then came our Bulgarian friends. Everyone brought us something: some fresh butter, bread, yogurt. And they would tell us, ‘Don’t worry! Do not believe that something bad will happen!… Look at us, if necessary, we will protect you! If they touch you, it is as if they touch us. Do you hear, do not be afraid! You will come back, and everything will be like old times...’ It was as if the little butter eased our tense nerves. Well, we were lucky then. After a couple of years, we realized what would have been our fate. Our friend Dr. Buko Isakov (a Jew from Samokov) who had accompanied the echelons of the Aegean Jews to the death camps and had experienced the horror of the doomed people, could not recover from the shock for a long time. [Annexation of Aegean Thrace to Bulgaria in WWII] 16 We did not need any words, his state was significant enough.

9th September 1944 brought my family and me the calmness and the hopes for a completely new and secure life. Then the Soviet army entered Bulgaria not as a conqueror, but as a liberator (except to the fascists). Let’s not forget that at that time there was a strong partisan movement in Bulgaria, which opposed the fascist regime imposed by the Bulgarian government. Naturally the government searched for and killed the partisans, burned their houses, terrorized their families. Many young people died between 1943 and 1944, including a lot of Jews – mostly young people from Plovdiv and Sofia. For example, my future husband, who is from Plovdiv, had been involved in antifascist activities and his life had been in real danger. Unfortunately, I do not know any details about that period of his life, because I met him after 1944.

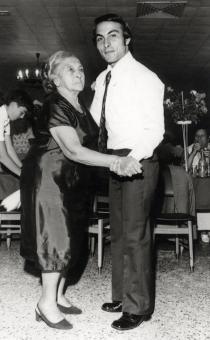

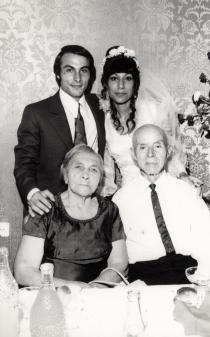

In 1947 I married Avram Melamed. We met through a group of Jewish friends from Plovdiv. I was in Plovdiv visiting my sister who had just married Rofat Revah from Plovdiv. Friends of his decided that I and Avram Melamed were perfect for each other and made everything possible to convince us in that. The main person ‘to blame’ for our marriage was Morits Assa, the former chairman of the Organization of Sofia Jews ‘Shalom’ 17, who lived in Plovdiv at that time. The story is quite unusual. I was introduced to Avram the day before he left for the USSR, where he was about to spend 5 years at a university (he graduated as an engineer there). At first, I thought I was only one of the many friends who came to see him off. But they had something else in mind, which, after all, I did not mind. While we were talking to each other, I suddenly heard Morits Assa saying ‘Lora and Avram are getting married tonight.’ And everyone started taking out some treats – potatoes, meat. ‘Congratulations! Happy wedding! Have a nice journey, Avram! And Lora will be here, working and waiting.’ At that time I was helping Morits with the administrative work, I was something like his secretary.

The next day Avram told me: ‘I am leaving.’ We left for Sofia where he had to take the plane to Moscow. There we went to marry before the registrar. But we had no witnesses. We went out on the street, looking for people to become our witnesses. We asked one stranger, and we found another acquaintance who agreed. And so, my husband left. But before that he said, ‘We will organize the wedding when I come back. And remember, no going out with other men.’ But a year passed, then a second, a third, a fifth... and we still had no wedding. Meanwhile my elder son Sheni [Shinto] was born in 1948.

At first I lived with my sister and my brother-in-law in Plovdiv. My sister’s husband advised me not to go to the relatives of my husband, because I did not know them, but I thought the right thing was to go and live with them. So, I went to live together with my parents-in-law in Plovdiv. My husband's sister and brother also lived with them. His brother's name was Samuel Melamed, but I do not remember her name. At that time I was working as a weaver. I gave all my money to them. In fact, everything was for them, even the food. The situation grew unbearable especially in 1948 when they understood that I was pregnant and I was going to have a baby.

Before Shinto was born my husband's relatives moved me from Plovdiv to Sofia. And there, while I was pregnant in the last month, they showed me where I would live. I went upstairs to the third floor and I nearly fell downstairs with the baby.... My husband's mother and brother were coming behind me. When my son was born, I wrote a letter to my husband and his answer was: ‘A boy, something to be proud of!’ He neither asked me how the delivery went, nor how the child was. Very often the money for the baby went for the needs of my husband's relatives. Then my brother Sinto came, took my child and gave him to my parents who had still not emigrated to Israel. They looked after young Shinto. At that time I was working as a weaver in the Slatina factory in Samokov.

I remember very well an unpleasant incident from my work as a weaver. Once a woman got hit (I can't say if it was an accident or done on purpose) and I went to help her, because her hand looked very bad. My decision was spontaneous, I wanted to help her and accompany her to a doctor. Then some boy came, a Bulgarian, and told me, ‘This is none of your business. You are a Jew...’ His words hurt me a lot. That was a very ugly case, which I want to forget, but I can't.

My family dispersed in 1948 when all my relatives except for me emigrated to Israel. 18 In fact, the decision was taken by my brothers and sister and my parents decided that they should follow their children. At that time I was already married. My sister Milka became a social worker in Israel (she had a university education in Bulgaria), my brother Sinto, who was studying medicine in Bulgaria became a famous doctor and my brother Miko (he is the only one of us with secondary education) became a lab chemist. They still live in Israel today and have good families, children and grandchildren. My sister has two boys, my brother Sinto – a son and a daughter, and my brother Miko – a son. All I know about their families is that Milka married before she left – to Rofat Revah in 1940, who was from Plovdiv and I lived with them in Samokov for a while.

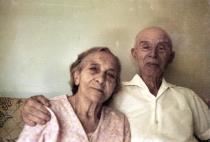

My husband returned from the USSR in 1951 as an engineer. He was also a communist so he found a job very fast. In that period I worked a lot, I was a member of the [communist] party, shared their ideas, read a lot. After 9th September 1944 when I went to Plovdiv to live with my sister. I worked as a typist in the propaganda department in the regional committee of the Fatherland Front 19, and later in the Regional Inspectorate on Information and Arts – Plovdiv where I was in charge of cultural information.

So, I was weaver in the 'Slatina' factory in Samokov. After 9th September 1944 – typist in the propaganda department at the regional committee of the Fatherland Front; later in charge of cultural information at the Regional Inspectorate on Information and Arts in Plovdiv. 1947-1998 - headed the personnel department of the City Committee of the Fatherland Front; instructor in the 'Propaganda' department of the BCP City Committee until 1952 ; head of the cultural department of the regional committee of the BCP (Bulgarian Communist Party) after my return to Samokov. 1952-1954 - instructor in lecture propaganda in the 'Propaganda' department of the Central Committee of the Dimitrov Communist Youth Union. 1954-1958 - Ministry of Culture in Sofia, department 'Community, headed the 'Propaganda' sector until 1958, when my department was renamed into 'Cultural and Educational Institutes'. Later I became an assistant in the sector 'Library Control' until 1960. June 1960 - head of the sector 'International Relations' in the Institute for Amateur Art Activities and after I returned from Spain I was once again head of the 'Propaganda' sector. In 1946 I became a head of department in ‘Septemvriiche’ and in charge of propaganda information of the UYW association 20 in the residential district. The same year I became member of the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP) and head of the Regional Inspectorate on Information and Arts. In 1947 I became a party secretary of the same organisation. I was also in charge of party affairs in the Centеr for Children’s Folklore Art, chaired the trade union committee there, I was a member of the committee on institutions at the Ministry of Education and Culture, member of the party committee at the Culture and Arts Committee, deputy party secretary of the Institute of Amateur Art Activities.

My son Shinto Avram Melamed and my daughter Iafa have an age difference of four years. Iafa was also born in Sofia in 1952. Shinto Avram Melamed has a university education in computer systems at the Higher Mechanical and Electrical Technical Institute in Sofia. My son graduated as a computer engineer (1960-65) and between 1965-71 he worked as an engineer in the Center on Applied Mathematics in the Higher Mathematics Institute; between 1972 and 1974 he was research associate in the Main Information Computer Center of the Ministry of Health; between 1974 and 1979 he headed that center, took part in the research of a national computer system for the health sector. Between 1979 and 1985 he was a director of a computer center, automobile plant 'Sofia' where he designed a control system with five innovations – certificates from the International Federation of Inventors’ Associations (IFIA); from 1985 to 1989 he was chief specialist in the Ministry of Transport in charge of the computerization of transport; from 1989 to 1991 he was deputy director of 'Mikrokom' (a state company) in charge of the computerization of the national post office system; from 1992 to 1994 he was adviser to thе chairman of First East International Bank; from 1993 to 1994 he was a representative of Bulgaria in the English-American Banktrust. From 1996 to 2001 Shinto was president of Geula Fund, and since 1991 he has been a president of the private consultant company 'Annex', in charge of foreign investment, interbank relations, financial and investment projects, their relations with the Bulgarian authorities and financial institutions.

My daughter Iafa Avram (nee Melamed) also has a university education in sociology from the Sofia University. After 9th November 1989 she worked in Bulgaria as a sociologist in the Sociology Institute at the Bulgarian Academy of Science, as a translator, spokeswoman for the Bulgarian National Radio, and in the Embassy of Portugal to Bulgaria. For a while she lived in Madrid, before 10th November 1989 21. Iafa knows French and Spanish.

My children are raised Jewish, so they feel Jews from an early age. My husband and I lived in Sofia and there were suitable Jewish youth groups for both Iafa and Sheni [Shinto] here. They gathered in the Jewish Cultural Home, the so-called Bet Am. They are proud of being Jews. So are their children.

Our family friends during the totalitarian regime were Jews, Bulgarians and Spanish –from our short stay in Spain. We gathered together on all religious Jewish holidays, mostly on Pesach. We had a great time. Now my friends are mostly from the Jewish community in Sofia. We gather often, talking, singing, laughing and dancing. We do not meet only on holidays. We gather daily at the Jewish Cultural Home, housing the administrative department of the Organization of Jews in Bulgaria 'Shalom', the Jewish community house 'Emil Shekerdjiiski', the editors' offices of 'Evreiski Vestnik' ['Jewish newspaper'] newspaper, and the magazine in Bulgarian and English 'Evreiski Godishnik' ['Jewish Year Book'], the Sunday children's school, the rehabilitation center for elderly people, the repatriation service 'Sochnut 22 ', which is the connection of the Bulgarian Jews to Israel, as well as the offices of the ‘Lauder' 23 and 'Joint' 24 foundations. To be honest, I must say that at the start of the democratic changes I received for a while aid from Switzerland and Germany, which helped us a lot.

I have been to Israel three times. I visited my relatives, friends and acquaintances. I remember that when I first arrived in Israel, I was welcomed by a sequence of sunny, bight, fresh and hot days. I was most fascinated by the thriving greenery in Israel, which was everywhere – in the cities, kibbutzim, flats, on the roofs, roads, in the synagogues and parks. I also noticed that the beautiful magnolias, rubber plants, jasmine, hedges, grass and all flowers were looked after with love not only by the common people, but also by municipal employees.

If someone dared to tear a flower from a bush, he would be scolded right away by a child or a passer-by. The terraces and gardens in Rishon le Zion, Rehovot and in the kibbutzim Hazorea, Shvaim, Nevo Betar fascinated me with the wonderful greenery in the midst of the desert where Israel is located. I found the Mediterranean Sea very warm, even in the end of the year. The scenery of Tel Aviv’s seaside is magnificent and inspiring, especially now. One visit of a stranger like me is enough to make him feel at home. The warm ‘boker tov’ [‘good morning’ in Hebrew] used to greet everyone you meet, the cordial ‘shalom’ when parting, the common ‘you’ melt the ice and make you a part of Israeli society. To be honest, I did not find it dangerous there and did not feel afraid of the threat of terrorism. Young children would play tennis, ride bicycles, go swimming, eat and drink and have fun under the watchful monitoring of planes and ships. I remember that one day the sea was a little bit dirty. I was walking along the shore with my husband, when looking at our feet we heard a voice from the loudspeakers saying to us, ‘Don’t worry, sir and madam, next to the changing rooms there is a device, which will wash away the bitumen. The device turned out to be a simple cylindrical brush soaked in petrol.

And the people in Israel really managed to have fun! We were in Tel Aviv during the visit of Luciano Pavarotti. He had to perform together with the Tel Aviv Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by the famous Zubin Meta. The tickets were 400 shekels each, which was quite expensive. But many Israeli were interested in music and the interest in the famous singer was even greater, so the sponsoring companies decided to place an enormous screen on the square, and benches in front of it. Naturally a multitude of music lovers filled the square, there were many people standing or sitting on the ground, all of them clapping and cheering and shouting with joy. I also witnessed the Sukkot celebrations in Israel. The same square was once again overfilled with people dancing, everyone singing, it was really spectacular. Both the young and the old had a really great time.

In the kosher restaurant of 'Shalom' we, the pensioners from Jewish origin, eat together every lunchtime, and on some weekdays some of us do exercises in the 'Health' club. We also meet on Saturdays in the 'Golden Age' club chaired by the former chairman of the Jewish community house Mois Saltiel. We meet various Jews from the area of art and science. I am also a member of the international women's organization 'WIZO' 25, whose meetings are both entertaining and educational.

If 9th September 1944 made my husband and me stay in Bulgaria (because we were communists), then 10th November 1989 made us think whether or not we should emigrate to Israel. Life in Bulgaria became hard, the conditions unacceptable, the country fell into a social crisis, inflation soared, unemployment became widespread. So, firstly Shinto and then Iafa decided to leave for Israel and see how life was there. They went to visit our relatives, stayed for a while and returned. My husband Avram and I had already prepared our documents to emigrate to Israel. But we decided to stay. Our children realized that our life in Israel would not be easy. We had already forgotten Ivrit, the social situation there was different, and Iafa decided that there was no point in emigrating if her child and her work are in Bulgaria. So, we all decided to stay in Bulgaria and I don't think we made a mistake.