Jozef Seweryn

Warsaw

Poland

Interviewer: Zuzanna Solakiewicz

Date of interview: May – October 2004

All my conversations with Mr. Jozef Seweryn began with looking over his identity cards: a former prisoner of Auschwitz, a member of the Association of Jewish Veterans, Union of War Invalids of the Republic of Poland and other similar ones; he always carries them in the pocket of his flannel shirt. Jozef Seweryn, before the war Jozef Kraus, always recalls the year 1938 when he begins talking about the past – the year when he was drafted into the army. He probably does so because this event divided his life into two parts. In 1939, when the war broke out 1, he was stationed in a regiment in southern Poland. The pre-war times – those of Jozef Kraus – have few connections with the post-war times, those of Jozef Seweryn. Before the war Jozef Kraus was a member of a Jewish bourgeois family, a boy with dreams and an imagination. Like many Jews from Cracow, he called himself a Pole of the Jewish faith. After the war Jozef Seweryn became a war veteran, he served many times as a witness in trials of war criminals. And all of this happened because, as he explains, he knew how to repair fountain pens, shave and cut hair. Today he lives with his wife in Warsaw, near the Vistula River. We met many times and tried to recreate the times of Jozef Kraus from the Podgorze district of Cracow and what happened later.

My family history

Growing up

During the war

After the war

Glossary

My grandfather on my mother’s side, Jakob Kraus, from Wieliczka [town near Cracow], came from a large and wealthy family. He was born in 1869. My grandfather’s parents ran a restaurant in Rajsko near Cracow. After their death, my grandfather sold the establishment and lost a lot of money that way. That was immediately after the war [World War I], before marks were replaced by zloty. The marks, which my grandfather received as payment, lost all of its value overnight.

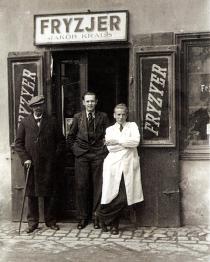

In the 1880s my grandfather opened a hairdressing salon in Cracow, in the Podgorze district [A district of Cracow, set up as a district for merchants and craftsmen; the Austrians exempted the residents from paying taxes, so people from all over the empire settled there. It was a workers’ district. There were some small and larger factories there: Piszinger, Optima – chocolate factories, wine factories, Wassanbergs’ mills, a wire fence factory – those were all Jewish enterprises.]. Several apprentices worked in the salon as well as my grandfather. They learned the trade at his salon and later left to start their own businesses. The apprentices would change every three years. It was a unisex salon. My grandfather had many customers. A cut cost one zloty.

My grandfather was also a feldsher. [The name Feldsher was derived from the German term Feldscher, which was coined in the 15th century. Feldscher means Field barber, and was the name of medieval barber-surgeons. They worked as primitive field surgeons for the German and Swiss Landsknecht until real military medical services were established by Prussia in the early 18th century. The term was then exported with Prussian officers and nobility to Russia. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feldsher] He applied leeches, pulled teeth and applied cupping glasses. The leeches would always be in a jar standing in the window of the hairdressing salon. My grandfather would get them from Budapest, Hungary. They would arrive once a week, through the mail. They were special leeches – medicinal; regular leeches could harm a human, bite in too deeply, but these would only break the skin and suck the blood. You put them behind the ear, on the mouth, on the gums.

My grandmother’s name was Felicja; her maiden name was Herzog. She was born in 1870. She was one year younger than my grandfather. Her family came from Czechia; she also had some relatives in Vienna [today Austria]. My grandmother was a real estate broker; she sold apartments and even houses. She used to make quite a lot of money; she had a talent for that job. She was a very cheerful and energetic person. She knew how to do business not only with Jews, but also with Poles. She even had her own lawyer – a young and talented Jew.

My grandparents got married in 1890. They had six children: Staszek, Dora, Heniek, Jozek, Hela and one more, whose name I don’t remember and who died shortly after birth. The oldest one was Uncle Staszek. He was born in 1891. He was the co-owner of the Royal Hotel in Cracow. It was a beautiful hotel, opposite Wawel [Editor’s note: The old seat of the Polish kings in Cracow]. He later opened a colonial store on Wielicka Street, where people from the neighborhood did their shopping.

Then there were Uncle Heniek, born in 1895, and Uncle Jozek, who was three years younger than Heniek. Heniek learned barbering; he ran a barbershop near Podgorze. He married a girl who came from a family of Jewish railroad workers. I can’t remember my aunt’s name, but I remember their daughter’s name – she was called Czesia. Uncle Jozek, who was born in 1898, learnt driving on his own; he was a car person – a car mechanic, he had a workshop near the Vistula River, he bought and sold cars.

Aunt Hela was born in 1900, she was the youngest. She married a Polish lieutenant. His name was Dzikowski. She converted to Catholicism then. They had a daughter – Lidzia. That marriage quickly fell apart. Later, she married a Polish officer, but she divorced him also. That second husband ran the Soldier’s House in Cracow and he didn’t have any toes on his feet – he lost them in a battle in 1918. My aunt also had a third husband, but I don’t remember that. She died some ten years ago. Her daughter is 86 years old and she lives in Warsaw; she’s a Catholic.

My mother, Dora, was born in 1892 or 1893 and was the second child in my grandparents’ family. She graduated from high school during the war [World War I] – first she went to an Austrian school, then a Polish one, where she passed her final exams. Everything changed during that war. Poverty was bad, there was nothing to eat, there was some aid from America and that was when my mother met my father. His name was Adolf Lehr. My mother got pregnant and he left for the war. He was badly wounded during the war, he became a cripple and wasn’t of any use after that. He didn’t return to Cracow, what happened to him later I don’t know. My mother stayed with her parents. I was born on 24th June 1917. My mother had no milk, so I had a wet-nurse – it was our neighbor, Mrs. Rokoszowa. I was friends with her son Tadek, who was my milk brother, throughout childhood.

When I was a few years old my mother left us. She met some Pole – Wladyslaw Seweryn –and married him. When she left I walked her with my grandparents to the tram stop. I stayed behind as she didn’t take me with her. She later changed her name to Elzbieta. Her husband worked on construction sites, she had a stall on the Maly Rynek market square. He didn’t want to keep in touch with our family. They had children, but I never met them.

I grew up with my grandparents, Jakob and Felicja Kraus. My grandparents didn’t have much time – they had their problems and their own affairs. I helped my grandfather in the shop. I remember he used to say, ‘Do this, do that, wash the floor, clean up.’ But my grandmother she had a gentler, caring approach, ‘Come and have some dinner, have some lunch and breakfast.’ My mother used to visit us sometimes.

We lived on 11 Limanowskiego Street, in a tenement house belonging to Mr. Brajer, who was of German origin. There were both Poles and Jews living in that house. It was a large building; there were two wings on both sides. Our apartment was in the back, on the first floor, and the hairdressing salon was on the ground floor, with an entrance from the street. My grandmother didn’t have a separate office. Customers would call her, my grandmother had a telephone and she took care of her business in the city.

There were three rooms in our apartment. My grandmother and grandfather slept in one of them; I slept in the second one and the housekeeper in the third. The housekeeper was Polish. When I was small, I also had a nanny. I don’t remember her name. The housekeeper cooked for the three of us and for my grandfather’s employees. Every morning my grandmother would tell her what to buy at the market. The market wasn’t far, some 100 meters from the salon. That’s where the tram stop was.

My grandparents were religious like all Jews. They went to pray on Saturday in the nearby prayer house on Rekawka [Street]. We celebrated Friday and holidays, like all Jews. Like it should have been. My grandfather didn’t have side locks or a beard, but he had a moustache. He wore suits – like a barber should. My grandmother didn’t wear a wig. The prayer house we went to looked modest. A house where you went to pray and that was all. People from the neighborhood would go there. The prayer books were in Hebrew. Women prayed on the balcony and men prayed downstairs. The rabbi from the prayer house lived opposite my grandfather’s hairdressing salon, but I don’t remember him well.

There were also Hasidim 2 living in Cracow, some even lived on our street. They lived in one tenement house and had their prayer house in that house. That prayer house was completely different than the one we attended. The Jews who came to our prayer house dressed Polish style, not Hasidic style. Hasidim dressed Jewish style; wore fur hats, side locks, chalats. There were few Jews of that kind – Hasidim. There were some, but not many. There were more of them in the east of Poland, in smaller cities, but not in Cracow or Lvov [today Ukraine].

At home, the holidays were observed according to tradition. We celebrated Passover like everyone else. Well, perhaps there was one difference; at home only seder dinner was festive and on the following days you’d normally go to work. And New Year was celebrated twice. First the religious New Year, Rosh Hashanah, and then the calendar New Year in the winter.

I liked Rosh Hashanah the best, because it was a very joyful holiday. A bit later the Festival of Shelters [Sukkot] was celebrated. In our house one booth would be built in the backyard for all the residents. That’s the way it was done then. We would go there with my grandfather when I was a boy. Inside the booth you would eat. It wasn’t very loud and pompous. It was like that in Kazimierz 3. But in Podgorze the holidays were more modest, quite poor. You’d just observe them for the sake of observance, and that was it.

My grandparents’ house was kosher. People cared about that at that time. There were those who respected the rules, but there were also those who didn’t. In my family my grandmother and grandfather respected them. They only bought things which you were allowed to buy and which you should, but their sons and daughters didn’t. My grandparents kept up what they were brought up in, but the young generation didn’t have time to live like they did. But when they visited my grandparents for the holidays, they behaved properly – according to tradition.

My grandparents somehow tolerated all this. When their daughter, Aunt Helena, got married to a Catholic officer and baptized her daughter a Catholic, they didn’t throw them out of the house. Helena and her husband would still visit us. Like all their other children.

When my uncles visited, they played cards with my grandfather – ‘66’ was the game. After supper they’d sit down at the table and play for money, for grosze [Polish currency]. We’d also go to the theater, but not often. My grandparents spent the summer in the mountains, in Szczawnica. Sometimes they’d also go to Vienna. I went to Szczawnica with my grandmother once, but usually my uncle and his wife would take me to a summer-house near Cracow.

There were about 70,000 Jews in all of Cracow between the wars. And about 100,000 Poles; there were also Hungarians, Czechs, Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians and even Swedes and some Bulgarians. It wasn’t bad for the Jews in Cracow. It was comfortable. Jews could behave freely there, like others. It was a city where different people lived, different nationalities. Everyone grew up there: Hungarians, Ukrainians, Russians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, and natives of Cracow, Jews. Jewish life was wonderful in Cracow, and it wasn’t just Jewish life. It was completely different in Cracow than it was in Warsaw, Gdansk or Poznan. Because Cracow and Lvov were two cities which used to belong to Austria before the war 4. If there were any problems, they were small, very small. There were some anti-Jewish incidents 5, but there were also anti-Ukrainian, anti-Hungarian, anti-Czech, because they were all equal citizens in Cracow.

Only Polish was spoken at our home. You have to understand this well: We were Poles of the Jewish faith: religion Jewish, nationality Polish. It was like this not only in our family, but also in other Jewish families of this kind, like the Herzes or the Krauses, in our tenement house in general – only Polish was spoken. [Editor’s note: Most Jews in Cracow described themselves in this way in the years between the wars, with the exception of the Hasidim.] With my great-grandparents – I don’t know. That was under Austrian rule, so perhaps it was different, but I don’t remember this because when I was born, it was already Poland 6 [Editor’s note: the interviewee was one year old at the time]. Among Jews like us, everyone was educated. They’d graduate from university or at least from high school. Jews were professionals. We were also more open to others, it would be said: a Pole of the Jewish faith, a Pole of the Roman Catholic faith. That was very important to all of us.

Pilsudski’s 7 funeral took place in Cracow in 1935. It was a huge event. I went to that funeral. First I stood on the market square. Then I followed the procession to Wawel and I saw how they carried Pilsudski into the cathedral. They buried him there, but I didn’t go inside. After a few days, I did go to see what it looked like. The marshal was lying in a metal sarcophagus, but his face was visible, as it was covered with a glass pane. You have to understand that everyone, Jews and Poles, liked Pilsudski. He was a hero.

I didn’t go to cheder. There were no religious education classes in the elementary school I attended on Jozefinska Street. Like most children from Podgorze, I took religious education classes at the elementary school on Kosciuszki Street; there were special Jewish religious education classes there. We used to meet in one of the rooms on the first floor and one Jew met with us and taught us Judaism. A private tutor prepared me for my bar mitzvah. He came and informed me, taught me religion. By the time I was 13, I had been taught everything that a Jew has to be taught. I had my bar mitzvah and then I forgot everything. I didn’t have time for it, I went to school and I was also earning some money working at a store, which sold dentistry supplies; and I had to help my grandfather on top of that. When was I supposed to have time for religion?

When I was a boy I really liked reading Karl May’s books, and also other books, about the war. [May, Karl (1842-1912): real name Carl Friedrich May, German author, best known for his wild west books set in the American West and similar stories set in the Orient and Middle East.] I practiced boxing. I was interested in photography. This really started by chance. When I was little, I would often have my picture taken and I liked it so much that I started to take pictures myself. I went to the theater on school outings. They would stage various instructive plays. And I always went to the cinema, whenever I wanted. I liked going to the cinema.

I was a member of the Polish Socialist Party 8. I joined it when I was 15 years old. I signed up because others were signing up. All of us – the boys from Podgorze – belonged to the PPS. There was nothing else in Podgorze but the PPS. I mean there were other groups – Zionists 9, Bundists 10, but they were very weak. We organized 1st May celebrations. Speakers would be invited to come; they explained what the PPS was, that it was an organization acting for the benefit of the working class. My grandmother and grandfather didn’t have anything against my joining this party. Many of my grandfather’s customers and all of his employees were in the PPS.

After I graduated from elementary school, I attended a three-year economic school. It was a good school. It cost 25 zloty a month. Part of this amount was covered by my grandfather and I paid some of it myself, from the money I earned at the dentistry supplies store. There were more or less ten Jews out of the 40 students in my class. All were assimilated, dressed in Polish clothing, behaved like Poles, so there were no problems with anti-Semitism. I passed my final exam in 1936. I worked for two years after graduating from school and then I was drafted into the army.

I was called up to the station in Cieszyn [town 80km south-west of Cracow] – the 4th Podhale Riflemen’s Regiment of the 21st Podhale Division was stationed there. Because I had graduated from high school, I was sent to the officer cadet school. But after three weeks I was moved to Biala [town 150km north-west of Cracow] to the 3rd Podhale Riflemen’s Regiment. This was because I was a Jew and they didn’t want Jews in the officer cadet school in Cieszyn. There were many Jews in the regiment in Biala – of my friends I remember Baruch Kostenbaum, Idzio Wittenberg from Kazimierz, Romek Kinstling from Podgorze. After that we all served on the front.

They moved me in September and we took the oath in October 1938, because we were considered to be honest, reliable and useful soldiers. We were later stationed in Zaolzie [territory on the Polish-Czechoslovakian border], which was occupied by Poland at that time. And we stayed there for a while and then returned to Biala. In March I got promoted to corporal and on 3rd May I became lance sergeant in the 3rd Podhale Riflemen’s Regiment. Our commander was married to a Jewess, the daughter of the owner of a wool factory.

I was supposed to leave the army on 30th September 1939, but the war broke out on 1st September, so I went off to fight the Germans. We soon got the order to retreat. In Wadowice I became the deputy reconnaissance commander. We had bicycles; the army was retreating and so we rode in front of everyone and then returned to the commander of the regiment with information. We were moving in the direction of Cracow, but we didn’t enter the city. We were ordered to march towards Wieliczka, where we joined other companies. Next, we retreated east.

The Russians took half of Poland and the Germans took the other half, and that was the end of Poland, and I was taken prisoner in the area of Lublin [town 140km south-east of Warsaw]. I was wounded during a skirmish and taken to a hospital, which, incidentally, was organized in a church. The Germans took me from there and we were ordered to move in the direction of Przemysl [south from Lublin]. During one of the stops I was sent with a friend of mine to get some water in a mess tin. They thought we wouldn’t be able to escape, because I was wounded, but of course we did run away. Over the mountains, through the forests, on side roads; we asked the farmers in the villages for food and something to drink. And we walked like this for quite some time, because I wasn’t walking very well, and this friend led me. Finally, we somehow reached Cracow.

It was late September 1939. I got back home and started working at my grandfather’s shop, as a barber. I had to, there was a war on. The owner of the house, Mr. Brajer, who was of German origin, didn’t want to be with the Germans; for them he was Polish, but that didn’t help us much. It was very cold inside the apartment, and we didn’t have any food. The ghetto was created in 1941 11. It was very crowded at home. Six families moved into our three-room apartment. It was extremely crowded; we finally moved to an apartment that was left after some relatives of ours had been killed. It was on Jozefinska Street, near Limanowskiego Street. It was a one-room apartment, so we could be there alone. The Germans came to our apartment in spring 1942 and murdered my grandmother and grandfather. They shot them, in their own beds, because they weren’t strong enough to go to work. I was there; they took me to work.

Regarding the rest of my family, my mother was living with her husband and children outside the ghetto. She pretended that she wasn’t Jewish. She had to, in order to survive. Someone finally denounced her and she was taken to Auschwitz. Uncle Jozek died in Auschwitz in July 1942, his number was 39 212. In 1941 Uncle Staszek and his wife and children went to Nowy Sacz. He was a member of the Judenrat 12 there. He and his entire family died in Nowy Sacz. Uncle Heniek was deported from Cracow and murdered with his wife in Belzec 13. Their daughter – Czesia – survived, she’s now living in Israel; she has two daughters and one son. Or perhaps she’s dead by now… And my milk brother – Tadek Rokosz, our neighbor’s son, managed to make it to England and he became a pilot in the RAF [Royal Air Force]. He survived the war. He died several years ago.

My childhood flair for photography was still there. I had my own photo camera – a Leica with a claw and a fixed focus lens. I’d always carry the camera around with me. I’d take pictures from the tram. One day I managed to take several pictures of a street round up of Jews in Podgorze. I took them from inside a coffin – through a knothole. This coffin was set up in the window of a funeral parlor, which was owned by my friend Staszek Gawlik, a Pole.

One night, in October 1942, I ran away from the ghetto. On my own I discovered an underground passage, running through houses which were connected to the ghetto. Nobody knew about this passage but me. Before the war I had had a girlfriend, a Pole; her name was Jadwiga Lepka and she worked in a bookstore. I ran away to her. I had to get Aryan papers. A priest agreed to give me a fake certificate of baptism, issued for Jozef Seweryn. Seweryn was the last name of my mother’s husband – the Catholic, the Pole. All his children were Seweryns and I became a Seweryn as well. I looked right, and I was taken for an Aryan. By the end of 1942 I married Jadwiga. I started working in the same bookstore where she worked. I had a section there – I repaired fountain pens, I had to make a living somehow. Our son Jacek was born at that time, but by then I was in the camp in Auschwitz.

I went back to the ghetto several times, I was active in the PPS, and we tried to help Jews. In November 1942 I was arrested, on the street, and not in a street round up. I met two Jews on Krakowska Street, in the Arkady cafe. When I left the cafe, I was caught by the Gestapo. First they sentenced me to death, and then they sent me to Auschwitz as Jozef Seweryn. Well, and I was Polish, an Aryan and so it stayed in the papers. Even in a book, published recently, listing the transports to Auschwitz, my nationality is listed as Polish. It was only several years ago that I went to Auschwitz and told them that I was a Jew.

I reached the camp in Auschwitz on 16th December 1942. I was there for more than two years. I was issued a number: 83782. Some experiments were conducted on me. They [the experiments] were carried out by a German physician, an SS soldier – Horst Schumann 14. These experiments were connected with fertility.

At the very beginning I met a friend from the 3rd Podhale Riflemen’s Regiment; we had served in the army together. When the war broke out in 1939, he would guide people through the mountains to Slovakia. He was a Pole, a mountaineer from Zakopane [town at the feet of the Tatra Mountains]. He arrived in Auschwitz in 1940, in the second transport. He recognized me immediately, as soon as I arrived; he was an old stager there, so he knew what to do and how to behave in the camp. He helped me a lot, he taught me everything. Others helped as well.

I survived, because the SS men needed me – I fixed their fountain pens. After several months of my stay in Auschwitz, the Germans wanted to find someone who could repair fountain pens and typewriters. I volunteered and was accepted. I worked for SS Unterscharführer Artur Breitwieser [1910-1978], he came from Lvov; before he became an SS man he had served in the 3rd Podhale Riflemen’s Regiment in Biala, at the same time as I did. Perhaps that’s why he chose me. I became his ‘Füllfederhaltermechaniker,’ that is his fountain-pen-fixer. The Germans had a lot of good fountain pens, Pelikans, Watermanns, Parkers, which they had got by looting the possessions of the Jews, but the ink they used was poor. Their pens needed to be rinsed and fixed every two months. And I knew how to repair pens, because I’d had that section in my wife’s bookstore. I worked for Breitwieser and for the other SS men, commandants, German physicians. They thought I was useful, so they even gave me a watch, so I wouldn’t be late when I came to see them. Besides, I didn’t just fix their pens; I would also shave them and give them haircuts. They addressed me ‘Sie’ [formal] and the others they called ‘Du verfluchter Hund’ – ‘You damned dog.’ And they killed them. I got the tools I needed for cutting hair and shaving – they used to be Jewish. I had more luck than sense.

I used to write letters to my wife; writing to your wife was permitted. She’d answer them. But my letters and her answers were so official. You couldn’t do it otherwise, and you had to write in German. And you couldn’t say anything more than, ‘I’m here – I am waiting – good bye.’ I couldn’t even write that I was hungry because they controlled all the letters.

One time at the camp, some time in 1943, an SS man came to see me, he had a higher rank than Breitwieser, and he told me, ‘Make me a barber’s wig and a beard – red.’ I said I would and that it would be ready in several days. When he came to pick it up he told me to get on his motorcycle and he took me to the commando, so I’d put the wig and the beard on him there. And then he told me to drive him to the theater, which was nearby, but it was on the other side of the fence. We got there and he said, ‘Now go to the camp.’ I answered, ‘I can’t go, there’s no one to guard me, if anyone sees me on this side of the fence, I’ll get shot.’ But he made me go, so I did. I was in prison clothes; wearing those stripes. I had a huge row at the fence; the guard took out his gun and shouted. I was so scared I almost shat in my pants, but he finally let me go. There were such stories.

In 1944 I was moved to Sachsenhausen 15, from there to Oranienburg [today Germany] and Ravensbruck 16, and finally to a camp in Barth [today Germany]. There was an aircraft factory there, where we all worked. We produced two-engine bombers. Most of the inmates were moved out of that camp on 30th April 1945. We were being led towards some town, when the Russians cut us off. The Germans surrounded us when they saw them approaching and started shooting at us. I survived.

The Russians put us on barges and we sailed somewhere in a northeastern direction, more or less. We sailed into some canal or bay, I don’t remember exactly. Anyway, a German ship attacked us and the barge was blown up. People were drowning, I held onto some log, I wanted to climb onto it, but I couldn’t because the Germans were still shooting. So I swam underneath it. I finally reached the shore. That night was 1st May 1945, going to the 2nd. I found some barn, I undressed, buried myself in the straw and waited until morning like this. I was very sick. I reached the city in the morning. It was Rostock [today Germany]. I met some of my friends there – those who had also managed to save themselves. We went on our way together, first to Szczecin, then to Poznan, Katowice. We’d sleep two, three nights in doss-houses set up by the Red Cross at train stations.

I finally arrived in Cracow. Straight away, I went to the bookstore, the one where my wife worked and where I had a section in 1942. I found her there and she took me home. Not to the place where we had been living before, but to a new one – in Kazimierz. She had got it when the Jews were being evacuated. Three rooms, one family in each room. She took me there and she started nursing me there.

When I came back I was thirty years old already and I had nothing any more. In 1945 I was assigned a job in Jelenia Gora [town 270 km north-west of Cracow by the German and Czech border]. Because after I came back, I reported to the PPS, someone from the PPS was going to Jelenia Gora and took me with him. They employed me in an office, which assigned apartments – I liquidated post-German property. First I went alone, my wife joined me later, as did her parents and her entire family. I found them all places to live and jobs in Jelenia Gora. For my mother-in-law and father-in-law – tailors in a dressmaking store that had belonged to some Germans. Everything was left there – sewing machines and other dressmaking tools. I gave my wife’s sister and her husband a beautiful apartment, in a tenement house that had belonged to some Germans. I also had my friends move to Jelenia Gora [Editor’s note: Mr. Seweryn didn’t want to say anything more about this, but he was probably a party official]. At that time many people came to that area – Polish and Jewish. Mostly those who had survived the war in Russia. Most of them came in 1945 and 1946.

After the war it was a lot worse with anti-Semitism, as if the Poles had learned it from the Germans and the Russians. Jews would be attacked, murdered, persecuted. There’s still some anti-Semitism, but right after the war it was a lot worse. People were leaving for Israel. At that time they would get people from all over Europe, from all over the world, to go to Israel. And in Poland they also suggested for the Jews to move there. So I went to Warsaw, to the embassy and I applied as well. I left in 1956 with my wife and children: 13-year-old Jacek and ten-year-old Krystyna.

We first arrived in Vienna. At first I wanted to stay there, but everyone said, ‘Go to Israel, see what it’s like there.’ I wish I hadn’t gone. I should have stayed in Vienna and asked for reparations from the Germans. But we went.

Israel looked nice in 1956. The state of Israel was created; a good thing that was; the Jews deserved it. I found a job in the aircraft industry as I had worked for the Germans in that field. I had experience from the camp, so when I came they employed me immediately, as a professional. I worked in the aircraft factory in Tel Aviv. There’s an airport there – Ben Gurion. I went with my wife and children. It was my wife who later decided that we had to go back. And that was it, no discussions. Our son was sick, respiratory tract problems – he couldn’t live in that climate. We left in 1959; I never went back there afterwards.

We first went to Italy, then to Vienna. I tried to convince my wife to stay there or move to Germany, but she would tell me – only Poland. So when she told me that it could only be Poland, I couldn’t say anything. We went back to Warsaw. I should have come back to Cracow. But we had relatives and friends in Warsaw, we could stay with them for some time; and Cyrankiewicz 17 was there. I knew Cyrankiewicz from Cracow, from before the war, we were in the PPS in Podgorze together, and later in the camp in Auschwitz. After three months he got us an apartment, he also helped me find work in a machine factory in the Praga district. I moved there in 1962 or 1963 from a Jewish metal plant which produced machines. It was a Jewish company, operated by the Jewish community. It was first located on 11 Listopada Street and later on 6 Twarda Street, but I didn’t work there after its move to Twarda Street.

I first went to a trial of war criminals as a witness in 1962. I also went in 1963, 1964 and later as well. I attended over a dozen trials. Four times in Berlin, and also in Hanover, Hamburg, Wuppertal and Frankfurt [all today Germany], several times. I was a good witness, because I had had personal contacts with many SS men. I had cut their hair, I had shaved them, so I remembered their faces well and I was able to recognize them. Among other trials, I attended the trial of Artur Breitwieser, the one who came from Lvov and who I served with in the army before the war, and whom I later met in Auschwitz – he was an SS man and I an inmate.

My wife died in 1972. A year later, I wrote a book. The title is ‘Mayn Yiddishe Mame’ because my mother and all of my folk died in Auschwitz. I was left alone. As the only one left of all the Herzogs and Krauses. This book comprises my memories about what happened during the war. From the time when I was drafted into the army in 1938 until the 3rd Podhale Riflemen’s Regiment and about what happened later. I wanted to have it published, but I didn’t succeed. At first they accepted it at the publisher’s, but then the management changed its decision and the publication was put off. I wanted to get the manuscript back and take it someplace else, but they made it difficult for me somehow. Nothing came together with that publishing business, so I finally gave up.

Krystyna went to the United States, to New York, after she graduated from college, in 1973. She’s still living there today. I visited her several times, but I was never very fond of the States. Jacek is 62 years old now; he’s retired. He worked in a factory for many years, I don’t recollect now what kind of a factory it was, but he was the director of some department. My children are Catholic. Of course, the children have always known that I’m Jewish. After all, we went to Israel together, but my wife, Jadwiga, was Catholic and she raised them as Catholics.

Today, the way I see it, Jewry isn’t as Jewish as before the war. It’s enough to go to a cemetery and compare the old section with the new one. The old tombstones – matzevas, and today? The same tombstones as in a Catholic cemetery. Besides, nowadays Jews are buried in coffins, and before the war it was a shroud and a bag of sand under the head; it was different, because they were buried the Jewish way back then.

And I’m old and sick now. My second wife, Henia [Henryka], whom I married in 1981, is also a Catholic. There was no Jewish world in Poland, there were no Jews. We live together in Warsaw. In 2001 I was appointed an officer by the president of the Republic of Poland, as a war veteran. I’m a veteran, a group one war invalid and a former prisoner of Auschwitz. I have identity cards and documents to prove that. I received some reparations from the Germans, but it wasn’t much. Renovating my apartment cost me more than what I got from them.

I’ve gone through so much in my life – so many things have happened. I was in Auschwitz. I was a witness in war trials – even after so many years they still invite me to Germany for various ceremonies. When I was in the army, I also achieved something. And how did I manage to achieve all of this? How is it that I am talking about it today? That I remember it at all?