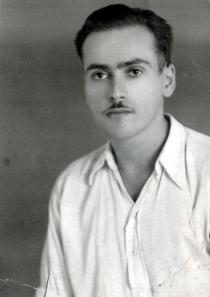

Alexander Gajdos

Alexander Gajdoš

Karlovy Vary

Česká republika

Rozhovor pořídil: Martin Korčok

Období vzniku rozhovoru: srpen 2005

Pán Alexander Gajdoš v súčasnosti pôsobí ako predseda Židovskej obce Karlovy Vary. Naše spoločné interview prebiehalo na obci v priestoroch jeho pracovne.

Rodina

Dětství

Za války

Po válce

Glosář

Starí rodičia z otcovej strany žili v čase otcovej mladosti v Nitre. Starý otec sa volal Bernát Goldberger a jeho manželka sa volala Terézia Goldbergerová. Žial už si nepamätám ako sa volala babička za slobodna a neviem ani to, odkiaľ pochádzali starí rodičia. Starí otec zomrel približne v roku 1936 alebo 1937 a babička pár rokov pred ním. Obaja sú pochovaní na židovskom cintoríne v Nitre. Zúčastnil som sa aj ich pohrebov. Pretože zomreli, keď som bol ešte mladý, pamätám sa na nich len veľmi matne. Starý otec bol zamlklí. Vždy sedel pred domom na lavičke s fajkou a len dumal. Mal svojho psa a ten sedel stále vedľa neho.

V Nitre bývali v štvrti pod hradom. V tom čase sa tam nachádzali malé prízemné rodinné domčeky. Nebola to však židovská štvrť. Židovskou štvrťou v Nitre boli Párovce. Starí rodičia bývali tiež v takom prízemnom rodinnom dome. Z dvora sa vchádzalo priamo do kuchyne. Okrem kuchyne mali ďalši tri izby. V jednej mali spálňu, potom bola ešte jedna malá izbička a napokon obývačka. Do tej obývačky sa chodilo asi tak, ako sa povie: „Raz za rok“. Elektrina a voda už boli v dome zavedené. V podstate tam viedli normálny život.

Žiadny z najbližších členov otcovej rodiny nepatril k pobožným Židom. Jeden z otcových [otec sa volal Heinrich Galik (changed from Goldberger)] bratov, Gyula [Gál (changed from Goldberger)] vlastnil obchod a dieľňu s rádiami. Otec mal štyroch súrodencov. Troch bratov a jednu sestru. Bratia sa volali Gyula, Rudi a Jožko, sestra Cecília. Cecília sa vydala za holiča, pána Horna. On však zomrel ešte na začiatku tridsiatych rokov [20. stor.]. Ja si na neho ani nepamätám.

Otcových rodičov som navštevoval každé leto. V podstate leto som trávil v Nitre. Väčšinou som býval u otcovej sestry Cecílie. Takže spával som u otcovej sestry a na obec som chodil vždy k niektorému z rodinných príslušníkov. Podľa toho, kedy ma kto pozval. Inak som väčšinu času trávil so svojim bratrancom, Alexandrom. Volali sme ho Sanyi, bol Cecilkiným synom. Chodievali sme sa spolu kúpať a tak. Do Nitry som prestal chodiť, až ked začala vojna.

Neviem aký bol materinský jazyk mojich starých rodičov ale so mnou sa rozprávali vždy slovensky. Okrem toho samozrejme ovládali aj maďarký a nemecký jazyk. Neboli pobožní ani neviedli kóšer domácnosť, ale sviatky sa v rodine držali. Starký mal obchod so zmiešaným tovarom. Mal jednu miestnosť a tam bolo všetko možné. Do obchodu sa vchádzalo hneď z kuchyne. Na dverách sa nachádzal zvonček, ktorý zazvonil, keď niekto vošiel. Niekto k nim potom vybehol z kuchyne a obslúžil. Inak si zvlášť na nejaké príbehy so starými rodičmi nespomínam. Mal som k nim ako dieťa určitý odstup. Ba dokonca ani neviem, kto bol susedom starých rodičov. Otec mi o nih neskôr tiež nezvykol rozprávať.

Mamičkiny rodičia pochádzali z Trstenej na Orave. Starý otec sa volal Markus Lubovič. Babičku sipamätať nemôžem, lebo zomrela ešte pred mojim narodením. Starý otec sa potom opäť oženil, ale ani meno jeho druhej manželky si už nepamätám. V Trstenej mal starký pekáreň. Nevedel by som však už o jeho pekárni nič bližšie povedať. Starý otec mal v čase mojej mladosti silnú cukrovku. Vtom čase ešte nebol inzulín, tak sa choroba nedala liečiť. Starý otec z nej takmer úplne oslepol. Nebol úplne slepý, ale takmer nič nevidel. Chodieval o paličke. Potom mu naši zohnali vo Vrútkach byt, kde sa presťahval spolu s druhou manželkou. Starali sa o nich mama spolu so sestrou Ruženou. Keďže vtedy starí ľudia nedostávai dôchodok, podporovali ich moji rodičia. Na meno druhej manželky starého otca sa už vôbec nepamätám. Rozprávala však maďarsky, pričom na Orave sa rozprávalo hlavne slovensky, aj medzi židovským obyvateľstvom. Starý otec ešte ovládal nemčinu a myslím, že aj maďarčinu. Obaja boli počas vojny deportovaní a zahynuli.

Starý otec mal so svojou prvou manželkou tri dievčatá. Moju matku, Sidy. Jej sestry sa volali Lina a Ružena. Z jeho druhého manželstva sa narodil syn Zoli. Lina sa vydala do Poľska za holiča do mesta Nowy Targ. Myslím, že sa volal Löwenberg. Ružena sa nikdy nevydala. Ostala stará dievka.

So starým otcom vo Vrútkach som trávil viacej času, ako s tým druhým zo Žiliny. Ale žiadny zvláštny vzťah sme si nevybudovali. Býval v byte jedna plus jedna, torý bol zariadený starým nábytkom. Z môjho vtedajšieho pohľadu nič moc. Vodu už mal samozrejme zavedenú. To, že koľko Židov žilo vo Vrútkach, neviem. Bola tam však celkom slušná komunita, s peknou synagógou. V tomto meste som mal dokonca aj bar micva. Starí rodičia z oboch strán boli neologickí Židia 1, to znamená, že veľké sviatky sa v rodine držali, šábes už pomenej a kóšer vôbec nie.

Otec sa volal Heinrich Goldberger. Narodil sa 17. júla 1898 v Nitre. Po vojne sa premenoval na Galík. To bola vtedy taká móda. Zomrel v roku 1978, mal presne osemdesiat rokov. Otec získal základné vzdelanie. Pracoval ako obchodný cestujúci. Týmto zamestnaním sa živil dovtedy, kým sa neosamostatnil. Neskôr si založil vlastný obchod v Žiline. Neviem kedy presne sa sťahoval otec do Žiliny, ale učinil tak kvôli práci a mojej matke. Pracovala totiž pre tú istú firmu ako môj otec. Bol to veľkoobchod Mendl a syn. Tam sa rodičia spoznali a neskôr sa vzali, lebo čakali mňa. Matka sa narodila v roku 1900 v Trstenej na Orave. To, že kedy zomrela neviem. Bola deportovaná a už sme sa o nej nič nedozvedeli.

Finančné zabezpečenie našej rodiny by som zaradil, medzi chudobu a strednú vrstvu. Keď boli zamestnaní u toho Mendla, mali celkom slušný plat. Keď sa otec osamostatnil, založil obchod so zmiešaným tovarom. Vzal si hromadu pôžičiek a potom prišiel krach na burze Wall Street a nastala kríza 2. Nebolo práce, prišiel exekútor a bol koniec. Ak sa dobre pamätám, otec mal ako prvý na okolí elektrický krájač na šunku a údeniny. Žiaľ, už po krachu burzy to nemal z čoho splácať. Okrem otca pracovala v obchode moja matka a ďalší zamestnanec, ktorý vykonával hrubé práce. Napríklad jazdil pre múku a pracoval v sklade.

Čo sa otcových politických názorov týka, ťažko povedať. Viete on sa so mnou ako s dieťaťom o takých veciach nerozprával. Predpokladám však, že bol sociálnym demokratom. Neviem to s určitosťou, len som to tak vydedukoval. Neviem o tom, že by bol otec členom nejakých spolkov a niečoho podobného. Tiež si spomínam, že za mlada slúžil ako vojak v 1. svetovej vojne ale nič bližšie k tomu neviem povedať. Vždy spomínal, že bol na vojne ale k nejakým konkrétnym historkám sa nedostal. Ak by sme sa mali rozprávať o otcových záľubách, tak on sa hlavne venoval obchodu. Okrem toho bol viac-menej sukničkár, to bol jeho koníček.

Rodičia sa medzi sebou zhovárali maďarským jazykom. S nami deťmi rozprávali slovensky. No o otcovi by som povedal, že bol sukničkár. To viete, mamu si bral preto, lebo ma už spolu čakali. Mama bola miernej povahy, dalo by sa povedať až uzavretej. Sama sa dokonca neukázala ani na ulici.

V Žiline sme bývali na viacerých miestach, podľa toho ako upadala naša finančná situácia. Vždy sme menili byt za lacnejší. Najprv sme bývali v centre nedaleko námestia, tam som sa narodil. Potom sme bývali smerom na celulózku. Neskôr sme sa presťahovali do časti mesta, kde bola budova vtedajšej elektrárne. Napokon sme museli prejsť do časti s mestskými činžiakmi, kde bolo najlacnejšie bývanie. Odtiaľ sme sa sťahovali do Vrútok. Z prvého bytu si už veľa nepamätám. Viem, že tam bola jedna veľká izba a ja som po nej jazdil dookola na trojkolke. Na ostatné miestnosti si už nespomeniem. Zo začiatku sme mali aj slúžky, ktoré varili a upratovali. Bývali spolu s nami približne do roku 1937. Vystriedalo sa ich viacero, takže si ich ani veľmi nepamätám. Ale keď som sa narodil, mal som dokonca aj kojnú. K žiadnej som si nevybudoval bližší vzťah. Že či sme mali za susedov Židov? My sme mali zakaždým niekoho iného. Veď stále sme sa len sťahovali. Ale boli to väčšinou nežidia. Rodičia nemali veľa blízkych priateľov. No tak otec mal nejaké známe, ženské, vdovy a ja neviem, niečo také. Tam sme občas chodili a inak nejak extra kamarát, tak to nemali. Tak to si nepamätám.

Sviatky sa v našej rodine nedržali veľmi prísne. V piatok mamička zapálila svičky a potom sa podávalo hlavne pečené kura. Neskôr, keď už otec nemal obchod a stal sa z neho obchodný cestujúci, v pondelok odišiel ale na piatok sa vždy vrátil domov. Jazdil po celom Slovensku. Predával múku pre rôzne mlyny. Do synagógy však veľmi nechodieval, to len na veľké sviatky. My sme navštevovali veľkú neologickú synagógu v Žiline. V Žiline žilo pred vojnou veľa Židov. Na sviatky bola veľká synagóga plná, napriek tomu, že za miesto sa muselo platiť a nie málo. Každý si tam platil svoje miesto.

Dodržiavali sme napríklad Roš hašana [židovský Nový rok – pozn. red.]. V tento deň sme sa doma navečerali a potom sa išlo modliť do synagógy. Inak si z toho večera nič zláštne nepamätám. Na Jom kipur [Deň zmierenia. Najslávnostnejšia udalosš v židovskom kalendáry – pozn. red.] sme sa potom postili, ale keď som niečo našiel, tak som si z toho uštipol. Jom kipur som však mal najradšej zo všetkých sviatkov. Všetko bolo biela a pôsobilo to tak slávnostne. No ale hlavne to, že sme sa na dvore synagógy zišli so všetkými kamarátmi. Vzadu vedľa synagógy bola židovská škola s veľkým dvorom a tam sme vyvádzali. Rodičia zatiaľ sedeli v synagóge. Občas sme sa tam aj my objavili a potom sme opäť zmizli. Chanuku [Chanuka: sviatok svetiel, tiež pripomína povstanie Makabejcov a opätovné vysvätenie chrámu v Jeruzaleme – pozn. red.] sme tiež ešte ako tak držali, hlavne sme v tom čase šli aj do synagógy ale napríklad Sukot [Sviatok stanov. Po celý týždeň, kedy sviatok prebieha, panuje jedinečná sviatočná atmosféra, pričom najpodstatnejšie je prebývať v suke – pozn. red.] a Purim [Purim: sviatok radosti. Ako hovorí kniha Ester, sviatok ustanovil Mordechaj na pamiatku toho, ako Božia prozreteľnosť zachránila Židov v perzskej ríši pred úplným vyhladením – pozn. red.] už vôbec nie. Dodržiavali sme ešte aj Pesach [Pesach: pripomína odchod izraelcov z egyptského zajatia a vyznačuje sa mnohými predpismy a zvykmi. Hlavný je zákaz konzumácie všetkého kvaseného – pozn. red.]. Večer sa čítalo z Hagady [Hagada: kniha zaznamenávajúca postupnosť domácej bohoslužby pri sédery. Hagada je v podstate prerozprávaním príbehu o východe Židov z Egypta podľa biblického podania – pozn. red.] a bol prestretý sviatočný stôl. Ale to ostatné, že by sme nejedli chlieb, tak to nie. Macesy boli, to je pravda ale jedli sme aj chlieb.

V meste boli aj ortodoxní Židia 3, síce ich bolo oveľa menej, no a oni držali všetko. S ortodoxnými Židmi som sa stretával aj ja. Dokonca ma otec poslal do ješívy v Žiline. Vyučoval nás taký malý zlostný chlapík. Dlho som sa však v tejto škole nevzdelával. Totiž moja mama už na tradície veľa nedala a doma sme nejedli kóšer 4. Preto bolo pre ňu normálne, že mi na olovrant zabalila žemľu so šunkou. Ten malý chlapík to uvidel, priskočil ku mne, vyviedol na dvor na „nakopal mi na zadok“. Povedal, aby som sa tam už viac neukazoval. To bol koniec môjmu náboženskému vzdelávaniu. Inak mne to vtedy ani nenapadlo, že čo som s tou šunkou spáchal.

Ako som už spomínal. Otec pochádzal z Nitry. Mal štyroch súrodencov, Július, každý ho volal Gyula. Ďalším bol Rudolf, nazývaný Rudi, Jozef a sestra Cecília. Najstarším otcovým bratom bol Jozef, on viedol obchod po starom otcovi. S rodinou žili v dome starého otca. Jeho manželka sa volala Malvína. Mali syna Tibora a dcéru Magdu. Obe deti prežili vojnu. Tibor sa vysťahoval do Ekvádora a Magda do Švédska.

Gyula bol približne o dva roky starší ako otec, to znamená, že sa mohol narodiť v roku 1896. Býval v Nitre spolu so svojou rodinou. Vlastnil obchod s rádiami, kde tie rádiá aj opravovali. Mal dvoch synov, Michala a Pistu [Pista, prezývka od mena Štefan – pozn. red.]. Vychádzali sme spolu celkom dobre. Keď som bol na prázdninách v Nitre, často som ich navštevoval. Chodili sme sa spolu kúpať alebo sme robili túry na vrch Zobor [Zobor: vrch pri meste Nitra (nadmorská výška 588 m), v pohorí Tríbeč – pozn. red.]. V Nitre bolo v tom čase kúpalisko pod hradom. Neviem, či to tam ešte stále je. Možno to už zastavali. Gyulova manželka sa volala Vilma, rodená Braunová. Bola to veľká dáma. Pochádzala z lepších kruhov. Bývali spolu na takzvanej Špitálskej ulici. V dome kde bývali mal Gyula aj obchod a dieľňu.

Tretí otcov brat sa volal Rudolf, čiže Rudi. On je o nejakých päť rokov starší ako otec. Vyštudoval stavebnú školu a pracoval ako architekt, v tom čase pán architekt. Rudi mal dvoch synov, Walter a Babi. Okrem nich mal ešte dcéru. Jej meno si už nepamätám. Bola trošku telesne postihnutá, mala menší hrb. Napokon však vyštudovala medicínu a stala sa lekárkou. Meno jeho manželky si už nepamätám. Počas vojny sa dostali do Terezína. Celá rodina prežila holokaust a po vojne utiekli do terajšieho Izraela.

Jediná otcova sestra sa volala Cecília. Vydala sa za pána Horna, ktorý mal v Nitre na Hlavnej ulici holičský salón. Obývali byt nad tým salónom s prístavbou smerom na dvor. Mali to zariadené celkom slušne. Jej manžel žiaľ veľmi skoro umrel. Mali jedného syna, volal sa Alexander, čiže Sanyi.

Druhú svetoú vojnu prežil len jeden z otcových súrodencov, Rudi. Ten sa potom spolu s rodinou vysťahoval v roku 1946 alebo 1947 do Palestíny. Po niekoľkých rokoch sa vrátili, znášali dobre tie klimatické podmienky. Ostatní otcovi súrodenci počas vojny zahynuli.

Mamička mala troch súrodencov. Dve sestry a jedného nevlastného brata. Najstaršia mamina sestra sa volala Lina. Vydala sa do poľského mesta Nowy Targ za holiča menom Löwenberg. Ja som toho pána ani nepoznal. Viem, že sa im narodili dve deti, ktoré s Linou počas vojny zahynuli. Prežil len ich otec, zachránil sa kdesi v Rusku.

Ďalšia mamina sestra Ružena tiež umrela počas vojny. Pred vojnou žila istý čas s nami v Žiline a potom i vo Vrútkach, kam sme sa presťahovali. S tetou Ruženou sme celkom dobre vychádzali. Znamená to asi toľko, že žiadne srdečné vzťahy to neboli ale ani napriek sme si nikdy nerobili. O mamičkinom najmladšom bratovi, volal sa Zoli, veľa povedať neviem. Bol o dosť starší ako ja, tak sme sa veľmi nekamarátili. Zomrel spolu s ostatnými počas holokaustu.

Ja, Alexander Gajdos [rodený Goldberger], som sa narodil 8. apríla 1924 v Žiline. Meno som si nechal zmeniť začiatkom päťdesiatych rokov. Že prečo som si vybral práve priezvisko Gajdoš? To ani tak nezáležalo na mne. Volal som sa tak ešte v nemeckom zajatí, k čomu sa ešte dostaneme. No a pri zmene som musel uviesť tri mená. Nadiktoval som Gajdoš, Gordon a to tretie si ani nepamätám a úrad mi vybral Gajdoš.

Ako malé dieťa som chodil do škôlky. U nás sa to volalo óvoda. Mal som celkom dobrú pani učiteľku. Dokonca do tej óvody som chodil rád. Nejaké extra spomienky na tú škôlku nemám. Pamätám sa len to, ako sme sa hrávli na dvore. Potom som prešiel na obecnú židovskú školu v Žiline. Bolo tam päť ročníkov – od prvej triedy po piatu. Chodili sme tam spolu chlapci a dievčatá. Chodilo tam pomerne dosť kresťanských detí, pretože to bola lepšia škola ako ostatné. Vyslovene som nemal rád matematiku a nemčinu. V škole som mal najradšej telocvik. Mali sme jedného vynikajúceho učiteľa, ktorý to s nami vedel. Toho sme mali naozaj veľmi radi. Samozrejme veľa sme cvičili a hrali hlavne hádzanú. Tá bola jednoduchá a na dvore stačili dve bránky. Dobité ruky i nohy samozrejme patrili k hre. Náš telocvikár sa volal Braun. Chodievali sme spolu aj na krátke výlety po okolí mesta. Hlavne na Dubeň a na okolité hrady. V židovskej škole sa samozrejme museli navštevovať aj hodiny judaizmu. To neexistovalo, aby sa na ne nechodilo. Náš vzťah k náboženskej výchove bol asi taký, že sme sa stále s rabínom hrali. Na jeho meno sa už nepamätám. Bol to starý pán a my sme mu vyvádzali strašné veci. Napríklad si pamätám, že sme mali zvonček a v polovici hodiny sme zazvonili, niekto vykríkol „zvonilo“. On na to „keď zvonilo, tak zvonilo“ a bol koniec hodiny. Na chodbe nás stretol riaditeľ, bol to obrovský chlap s trstenicou, ešte sa nás pýtal kam ideme. My sme mu povedali, že rabín povedal, že zvonilo. On povedal: „Veď ešte nemohlo zvoniť.“

Riaditeľ používal aj telesné tresty. Napríklad s nami chodil aj jeden zaostalejší chlapec a ten vždy niečo vyviedol dievčatám. Napríklad kým cvičili, tak im zobral šaty zo šatne a tak. Mimo školy sme boli partia židovských chlapcov, všade sme spolu chodili a trávili spolu veľa času. Boli sme tak piati. Okrem nás bola ešte jedna partia židovských chlapcov a tak sme proti sebe bojovali, hádzali kamene a tak. Mali sme asi desať, jedenásť rokov.

Vo Vrútkach som sa pripravoval aj na obrad bar micva [Bar micva: „syn prikázania“, židovský chlapec, ktorý dosiahol trinásť rokov. Obrad, pri ktorom je chlapec prehlásený bar micvou, od tejto chvíle musí plniť všetky prikázania predpísané Tórou – pozn. red.]. Otec mi zjednal vyučovanie u istého rabína. Bol to mladý človek nižšej postavy. Pochádzal z Čiech a patril k neológom. Ten ma učil. Išlo hlavne o to, aby som sa naučil text, ktorý mám prečítať počas obradu. Iné sa tam po mne ani nechcelo. No a do bar micva som sa to nejako naučil. Samotná bar micva prebiahala v synagóge vo Vrútkach. Predvolali ma k Tóre, prečítal som text a to bolo všetko. Na nejakú oslavu doma si ani nespomínam, a nespomínam si ani na to, čo som pri tejto príležitosti dostal nejaké darčeky.

Vo veku mojich štrnástich som začal pociťovať protižidovské nálady. Vychodil som päť tried obecnej židovskej školy a potom som sa dostal do gymnázia 5. Z gymnázia ma vylúčili v tretej triede, potom som už nesmel chodiť v Žiline do školy. Ale inak sa nič zvláštne nedialo, len že som nemohol chodiť do školy. Že by nás nejak inak diskriminovali, tak to nebolo. Akurát tí sopľoši na ulici vykrikovali: „Žid, smrad, kolovrat!“, ale tie nadávky sme poznali aj predtým.

Práve v tom období sme sa sťahovali zo Žiliny do Vrútok, kde som nastúpil do štvrtej meštianky. Tde priamo vo Vrútkach ma na školu nevzali. Musel som každý deň dochádzať vlakom do neďalekej obce Varín. Židom som tam bol iba ja. V podstate si ma nikto nevšímal. Všetci učitelia boli v Hlinkovej garde 6, dokonca aj riaditeľ, pre nich som ako keby ani neexistoval. Sedával so v prvej lavici, ale ani raz ma nevyvolali, napriek tomu som dostal na vysvedčenie samé trojky. Bolo to v roku 1939. So spolužiakmi som vychádzal dobre, tam nebol žiadny problém. Bolo medi nimi aj pár Čechov, ktorých nevyhnali 7 zo Slovenska. Priatelil som sa najmä s tými, ktorí spolu so mnou dochádzali. Boli sme štyria, ktorí sme jazli vlakom z Vrútok do Varína a večer naspäť.

Okrem mňa sa rodičom narodila moja sestra Viera. Narodila sa v Žiline v roku 1927. Vychádzali sme spolu dobre, ale nie až natoľko aby sme chodili spolu von. Každý z nás mal svojich kamarátov. Sestra žiaľ vojnu neprežila. Do lágru išla spolu s mamou, ale vôbec nevieme, kde zmizli. Napriek tomu, že sme po nich pátrali, stopa sa stratila. V priebehu vojny nás celú rodinu internovali v zbernom tábore v Žiline v roku 1942 a boli sme tam do vypuknutia Slovenského národného povstania v roku 1944 8. V tom období, medzi rokom 1942 a 1944, keď nešli žiadne deportácie 9, pracovali sme v tom žilinskom tábore.

V tábore bol v tom období celkom dobrý život. Chodili sme pracovať na výstavbu športového štadióna v Žiline. Aj môj otec tam pracoval. Štadión sa nachádzal neďaleko rieky Váh. Nebola to až taká ťažká práca. Dozorcovia, gardisti, z tábora nás tam doviedli. Oni potom niekde zaliezli, alebo sa rozišli na pivo. Bol tam jeden človek, ktorý nás navygoval a to bol slušný chlap. Mama pracovala v tábore v kuchyni a sestra nerobila nič.

Život bol v tom čase naozaj znesiteľný. Dokonca som chodieval aj do mesta. Ani hviezdu som nenosil 10, v živote som ju nemal. Nikdy som sa ani nedopočul o prípade, že by bol za to niekto niekoho udal. My, ktorí sme boli zo žilinského lágra, sme hviezdu nenosili. V tábre som býval s ďalšími piatimi chlapmi. Sem tam niekto utiekol, ale veľmi sa neutekalo. O tom, čo sa deje v Poľsku sme sa dozvedali od železničiarov, ktorí sprevádzali transporty po hranice s Poľskom. Železničiari nám priniesli správu o krematóriách v Osvienčime. Myslím, že od nich sa to rozšírilo.

Počas povstania 8 sa otec, matka a sestra ukryli v lesoch v okolí Rajeckých Teplíc. Tam ich potom všetkých chytili. Otca previezli niekam inam, kde mamu a sestru a tak sa mu podarilo prežiť. Otec sa dostal do Sachsenhausenu a potom do Buchenwaldu. No a matku so sestrou vzali do ženského tábora v Ravensbrücku a tam sa ich stopa stratila. Ja som sa počas povstania pridal k armáde. V Žiline bola vojenská posádka, no a celá táto posádka sa stiahla k Martinu, do Strečna. Pred vojnou som bol členom mládežnického hnutia Hašomer Hacair 11, ale nie preto som sa pridal k armáde. Človek sa pridával tam, kde bola nádej na prežitie.

Na Strečne sme boli v nejakej obrane. Kopali sme zákopy a mali za úlohu podržať záložnú líniu. Samozrejme neboli sme len pasívnymi pozorovateľmi. Raz sme dostali rozkaz zaútočiť na železničnú trať s tunelom. Ako sme sa tam približovali, zrazu sa objavil Tiger [Tiger: nemecký tank, sériovo vyrábaný od roku 1942 – pozn. red.] a začal po nás páliť. Stiahli sme sa do zákopov. Boli tam s nami francúzski partizáni, ktorí boli na Slovensku v zajatí a počas povstania sa im podarilo utiecť. Viac o ich osude neviem, veľmi som sa s nimi nestretával. V našom odiely sme boli len dvaja Židia, ja a môj vzdialený bratranec Elemér Diamant. Žial neviem, či prežil vojnu, lebo potom sa naše cesty rozišli.

Časom sme útočili na nejakých Nemcov ukrytých v lesíku. Tam po mne začal nejaký Nemec strieľať. Žiaľ aj ma trafil. Prestrelil mi rameno, guľka našťastie vyšla druhou stranou. Zranenie bolo pomerne ťažké, ale dostali ma z neho. Najprv ma z miesta, kde ma zasiahla guľka odtiahli. Ťahali ma po zemi a na bezpečnom mieste so mnou vybehli na cestu. Po čase pre mňa prišla sanitka a vzala ma do nemocnice v Martine. Tam som bol jeden deň, pretože Nemci prerazili frontu a granáty dopadali až na nemocnicu. Rýchlo nás evakuovali do mesta Sliač.

Povstalecké územie bolo už úplne malé. V podstate len miesta v okolí obcí Banská Bystrica, Sliač a Brezno. Všetko ostatné už bolo buť obsadené alebo obkľúčené. V Sliači sa ma opýtali, či môžem chodiť. Keďže chodiť som vedel, prepustli ma z nemocnice. Ešte som sa tam stretol s Elemérom, pretože on bol tiež v nemocnici. Počas bojov pri meste Vrútky sa dostal do nejakej mely a utrpel z toho šok. Oboch nás prepustili takmer súčasne. Ja som si to namieril na hlavný stan partizánov a on povedal, že už tam nepôjde, radšej vymyslí niečo iné. Tak sme sa rozišli a od tej doby sme sa nestretli. Z nemocnice som odišiel do Banskej Bystrice, na hlavný štáb. Tam ma vzali k strážnemu oddielu. Držal som stráž pred hlavným štábom v Banskej Bystrici na hlavnom námestí.

Nemci sa tlačili aj do Banskej Bystrice. Evakuovalo sa do hôr, Staré Hory [Staré Hory: horská obec v Starohorskej doline, okres Banská Bystrica – pozn. red.], Donovaly [Donovaly: horská obec situovaná medzi pohoriami Veľká Fatra a Starohorské Vrchy, okres Banská Bystrica – pozn. red.], Kozí Chrbát [Kozí Chrbát: v súčasnosti lesná rezervácia ležiaca na severnej strane Nízkych Tatier – pozn. red.] a tak ďalej až cez Chabenec [Chabenec (1955 m): je mohutný horský masív v Nízkych Tatrách – pozn. red.]. Na tom Chabenci napríklad zmrzol Šverma 12. Mnoho z nás tam vtedy dostalo dyzentériu [dyzentéria: vážna infekčná črevná choroba. Prejavuje sa ťažkou hnačkou s prímesou krvi a horúčkou, ktorú sprevádzajú bolesti brucha – pozn. red.]. Všetkých, ktorí sme ju dostali nás ubytovali zvlášť v jednej zemľanke [zemľanka: podzemný úkryt, obyčajne vojenský – pozn. red.]. Odtiaľ nás však poslal preč jeden miestny občan so slovami: „Tu nemôžete byť, my vás nemôžeme živiť, sami nemáme čo žrať!“ Oznámili nám, že nás vezmú na kraj lesa, kde sú dediny a sami si budeme musieť niečo zohnať od miestnych ľudí. V tom čase som sa zoznámil s jedným Čechom z Ostravy. Na jeho meno sa už žiaľ nepamätám. S ním sme to odvtedy spolu „ťahali“. Odviedli nás na kraj lesa a povedali rozchod. Tam nám oznámili, že sme stále vedení ako partizáni z odielu, ktorého meno si už tiež nepamätám. Povedali nám aj, že keď niečo prezradíme, tak si nás nájdu.

Celé sa to udialo na prelome novembra a decembra 1944. S mojim českým kamarátom sme si našli celkom slušné miesto a jedným kopcom a vykopali si buker. Najbližšia dedina bola z toho miesta vzdialená na tri hodiny chôdze. Tak sme si povedali, že tu ostaneme a každý večer sa vyberieme do dediny, vyžobrať si nejaké jedlo a zásoby. Pretože, ak by napadlo veľa snehu, aby sme neumreli hladom. Našťastie v tom období ešte nemol sneh, pretože sme sa nachádzali kdesi v Nízkych Tatrách [Nízke Tatry: 80 km dlhé pohorie nachádzajúce sa na Slovensku – pozn. red.]. Takto sme denne chodili do dediny. Vždy sme sanajedli. Niekde nám dali fazuľu, inde zemiaky a tak. Pokiaľ to bolo možné, vzali sme si aj zásoby. Keď sme už mali dostatok zásob, povedali sme si: „No, teraz sa pôjdeme najesť naposledy!“

Tak sme sa išli naposledy najesť. Zabúchali sme u jedných na dvere a otvorila veľmi slušná selka. Povedala: „Ó vy chudáci!“ Hneď nám dala večeru. Potom si všimla naše oblečenie a so slovami: „Veď vás žerú vši, ja vám to vyperem“, nás nechala vyzliecť a uložila do postele, do perín! My sme jej povedali nech nás zobudí akonáhle sa začne rozodnievať. Na čo odvetila: „Samozrejme, samozrejme“. No a naraz buchoty v dedine. Nemci hulákali. Veci sme už mali vyprané, suché a rýchlo sme sa obliekli. Ešte sme jej hovorili „Prečo ste nás nevzbudila?“ „Mne vás bolo tak ľúto, vy ste tak krásne spali.“ Vylietli sme z baráku a hneď na námestí jedna hliadka s guľometom, na druhom konci ďalšia hliadka s guľometom. Nemci už chodili z baráku do baráku. Tak sme vyleteli zadom. Obišli sme námestie a dostali sa do úhozu. Už sme boli vonku z dediny. Naraz sa oproti nám objavili dvaja Nemci. Debili tam museli ísť práve tým úhozom a my dvaja dotrhaní civili im rovno naproti. Už sme sa minuli, už sme boli asi desať krokov od seba a naraz nás zastavili. Niečo sa im nezdalo a jeden z nich zakričal: „Hej partizán!“ Tak nás zobrali. Zhromaždili nás na námestí v strede dediny. Aby sme nešli len tak naprázdno, každému naložili s nábojmi. Takže sme mali čo niesť cez ten sneh, ktorý medzičasom napadal.

Napokon nás posadili do vlaku a odviezli do väzenia v Banskej Bystrici. Tam sme boli od začiatku decembra do konca februára. No a tam v tej väznici sme vegetovali tie dva, tri mesiace. Občas niekedy kravál, niekoho vyhnali na Kremničku 13. Vyháňali ich psami, gulometmi. Potom bolo týždeň ticho. Potom ich zase nahromaždili a zase ich potom išli vystrielať. No a my sme tam stále vegetovali v tej izbe. Bol tam jeden Ukrajinec, ja a ešte dvaja Židia. Nevedeli s určitosťou, že sme Židia ale mysleli si to. Naraz nás koncom februára vyviedli a prišiel nejaký Slovák, s vysokou šaržou. To boli Slováci. Strážila nás slovenská väzenská stráž. Krútil hlavou, že ako je možné, že sme stále tam. Oznámili nám: „Tí, čo tu boli pred vami, tak tých všetkých už pozabíjali v Kremničke!“ Na našu izbu akosi zabudli. Tak otvorili dvere a pýtali sa „čo tu robíte? Už tu nemáte byť!“ No my sme hovorili: „Nemáme tu byť?“ Podľa papierov malo byť celé väzenie prázdne. Kartotéky sa už ničili, lebo oslobodzovacia armáda už dobíjala blízke Brezno a oni už chceli evakuovať aj Banskú Bystricu.

Nás si teda zapísali a odišli, proste týždeň pokoj. Potom prišiel znovu iný a zase si nás zapísal. No a potom za tri, alebo štyri dni prišiel esesák s tým, že ideme na výsluch. Cez ulicu bol banskobystrický súd a tam mali sídlo. Tak tam nás odviedli na chodbu. Potom prišiel ďalší, pýtal si meno. Nadiktoval som Gajdoš, narodený v Žiline. Zapísal si to a odišiel.

Zachvíľku prišiel nejaký vysoký dôstojník, sudeťák 14, rozprával česky a hovorí: „Ja vám teraz dám prepúšťacie papiere. Bežte domov. Nie aby ste bežali na východ! Lebo, keď vás tam uvidia naši vojaci takto otrhane, tak vás postrielajú.“ Tak sme dostali papier a išli sme. S tým kamarátom z Čiech sme si povedali: „Čo budeme robiť? Samozrejme vybali sme sa na východ. Hneď v prvej dedine za Banskou Bystricou nás pristavil jeden chlap. My sme mu ukázali papiere, že nás práve prepustili a že sa potrebujeme dostať k partizánskej jednotke. Tak dobre, povedal. Tu máte večeru, vyspíte sa a skoro ráno vás prevediem k hlavnej ceste a ukážem vám, kadiaľ máte ísť.

Či sa tým ľuďom dalo dôverovať? Čo iného nám zostávalo? On vyzeral skutočne tak seriózne. Ráno nás previedol na cestu a ukázal smer. Mali sme sa dostať do obce Priechod, kde sa nachádzali maďarské jednotky, ktoré sa odtrhli od Nemcov. My sme teda šli tým smerom. Po čase sa kamarát potreboval vysrať. Tak si vyliezol na pole, poobzeral sa dookola a uvidel nejakú postavu v bielom ako tam stojí a pozerá sa na nás. Dali sme sa na útek. Bežali sme otvoreným poľom. Keď sme sa zastavili, že už sme dosť ďaleko, pred nami sme zbadali zástup nemeckých vojakov. Zbadali nás! Nemohli sme robiť nič iné, len im kráčať naproti. Samozrejme nás zajali a odiedli do nejakej dediny. Predviedli nás pred veliteľa so slovami, že nás chytili a buď budeme partizáni alebo banditi a treba nás zlikvidovať. Veliteľ sa nás pýtal, či rozprávame nemecky. Keďže som si niečo pamätal zo školy, tak som mu povedal, že nás práve pustili. Ukázali sme mu papiere. Potom sa začal hádať s ďalším vojakom, či nás zlikvidujú alebo nie. Vojak bol za likvidáciu, veliteľ proti. Napokon veliteľ rozkázal, že nasledujúcu noc budeme spať s ním v jednej izbe. Keď sme ostali sami, nám po nemecky hovorí: „Musíte spať so mnou, lebo on je nacista a ja za neho neručím.“

Na druhý deň nás poslal s vojakom späť do Banskej Bystrice, aby sa presvedčil, či nás skutočne pustili. Te človek, sudetský Nemec, ktorý nám vypísal papiere nás zbadal. Podišiel k nám a začal rozprávať česky, aby mu nás sprievodca nerozumel. „Vy dvaja, čo som vám povedal, že máte ísť rovno na západ a že sa nemáte motať!“ Nemecký vojak samozrejme ničomu nerozumel a hlásil, že sme banditi a máme falošné papiere. On mu hovorí „Vy hovoríte o mojom podpise, že je falošný?!“ On mu tak vynadal, že až! Ešte aj nám sa ušlo, že: „Čo čumíte, okamžite sa strate, ak vás ešte raz privezú, potom bude koniec!“ Tak sme zase vybehli von. Za nami vybehol ten nemecký vojak, sadol na voz a „utekal“ rýchlo preč.

My sme sa opäť vybrali tou istou cestou ako včera, napokon už sme ju ako tak poznali. Na druhý krát sa nám podarilo dostať do deniny Priechod. Hneď nás tam zadržala stráž. Pýtali sa, čo tu chceme. Povedali sme, že ideme za partizánmi. Tam sa nás ujal nejaký chlap v civile. Rozprával slovensky aj maďarsky. Povedali sme mu, že by sme sa radi pridali k nejakej partizánskej jednotke. No tak dobre ale najprv sa navečerajte. Tí Maďari sa ešte mali dobre, mali buchty s makom. Tak sme sa tam nažrali!

Územie, na ktorom sme sa ocitli bolo slobodné a to tým, že maďarská vojenská jednotka sa odtrhla od Nemcov. Nakoniec sa dostala reč k tomu, kde budeme spať. Oznámili nám, že nad dedinou je hájovňa s partizánskym oddielom. Bolo tam pár partizánov a Maďarov. Presunuli sme sa do tej hájovne. Tam sme dostali ďalšiu večeru, zase nejaké buchty a dobroty. Vyfasovali sme zelenú československú uniformu a flintu. Napokon sme sa pobrali spať. Mohlo nás tam byť asi päťdesiat, šesťdesiat ľudí. Ráno, mohlo byť tak päť hodín, nás zobudili výkriky a streľba. Dedinu Priechod ráno obkľúčili Nemci. Použili lesť. Keďže tam boli maďarskí vojaci, Nemci poslali napred iných maďarských vojakov, ktorí boli na ich strane. Tým sa podarilo dostať k strážam, pretože na ich výzvu odpoveali maďarským jazykom. Takto stráže odzbrojili a vošli do dediny. Ako ľudia vybiehali z domov, Nemci ich rovno strieľali, ako zajace. Časť mužov pozbierali a vyniesli na koniec dediny pod strmý kopec. Kázali im utekať. Ako utekali, všetkých postrieľali. Ujsť sa podarilo len jednému nemeckému chlapcovi, mohol mať tak šesťnásť, sedemnásť rokov. Tento chlapec sa ešte predtým pridal k partizánom. Bol jediným z mužov, komu sa podarilo prežiť. Nemci napokon dedinu vypálili. Niektorým ženám sa to podarilo prežiť a oni potom zostali žiť v tej vyplienenej dedine.

Odstupom času sme sa dozvedeli, že zradcom bol chlap, ktorý sa nás ujal po príchode do dediny a nakŕmil buchtami. Ak by nás večer nebol poslal hore do hájovne k partizánom, už by som tu nebol. Nás defakto zachránil. Jeho úlohou bolo zháňať zásoby a zároveň pracoval aj pre Nemcov ako agent. Nakoniec aj jeho chytli Rusi a popravili ho. My sme ostali istý čas v hájovni. Odtiaľ sme chodievali na hliadky k okolitým dedinám, napríklad k dedine Podkonice a tak. Všade už boli Nemci. Len sme počuli ako pri nás vŕzga sneh. Pretože ich hliadky prišli až na kraj dedín, k lesu a potom sa opäť stiahli. Napriek tomu, že od nás boli len na niekoľko krokov, nemohli sme s nimi ísť do boja. Bolo by to pre nás beznádejné. Vedeli sme, že by to bolo beznádejné. Cez Podkonice viedla aj hlavná ústupová cesta Nemcov smerom na Ružomberok. My sme sa z hájovne postupne presunuli do bunkrov v lese, kde sme držali hliadky. Odtiaľ sme koncom februára, začiatkom marca, pokračovali cez Chabenec a Nízke Tatry, do Brezna. Brezno už bolo oslobodené. Zdržiavali sa tam rumunskí vojaci. Tam nás rozdelili. Maďarskí vojaci, ktorí boli s nami, šli dole na juh. Česi a Slováci pochodovali smerom na Poprad. Pešo z Brezna do Popradu [priama cestná vzdialenosť medzi mestami Brezno a Poprad je približne 90 km – pozn. red.]!

Po príchode do Popradu som sa hlásil do Prvého československého armádneho zboru. Tam som bol ovedený do poddôsojníckej školy. Dostal som peknú uniformu, zbraň a tam som slúžil do júna 1945. Poddôstojníckuškolu v armádnom zbore som absolvoval s hodnosťou slobodník. Odvtedy som sa ešte prepracoval na podplukovníka československej armády. Po škole som odišiel s ostatnými vojakmi, v rámci výcviku, pešo z Popradu do Martina [priama cestná vzdialenosť medzi mestami Brezno a Poprad je približne 130 km – pozn. red.]. Kráčali sme tri, alebo štyri dni. V Martine sme sa stretli s prezidentom Benešom 15, ktorý prišiel z Košíc 16. Tam sme nastúpili na autá a poslali nás ako zálohu na Moravu, kde sa ešte bojovalo. Vojakom pred nami sa však vždy darilo frontu preraziť a tak sme sa my priamo bojov nezúčastnili. Takto sme šli za frontou, až do Prahy.

V Prahe sme ako vojaci chodili na „cvičák“. Nacvičovali sme napríkld boj v uliciach mesta. Bolo to na Bílej hore. Tam vybehovali babičky s maskami a pokrikovali: „Ježiš Mária, Nemci sa opäť vrátili.“ Oni nevedeli, že je to výcvik, a že používame len slepé náboje. V uliciach bol rachot a babičky sa preto chceli dostať do úkrytu. My sme im hovorili: „Babi, to je len tak, to nie je skutočné.“ Koncom júna nás poslali späť na Slovensko, do vojenského útvaru v Nitre, odkiaľ ma potom prepustili do civilu.

Počas môjho pôsobenia v Prahe som kontaktoval bývalého starostu Vrútok. Zároveň bol zástupcom veliteľa Hlinkovej gardy v meste, ale aj náš ochráca a rodinný priateľ. On mi povedal, že otec sa vrátil a žije v Žiline. Tak to som vedel. Počas môjho pobytu v Nitre som sa ubytoval u otcovho brata, Rudiho. Prežil vojnu v Terezíne 17. Spal som u neho na žehliacej doske. Po niekoľkých dňoch som sa vybral v nákladnom vagóne z Nitry do Žiliny.

V Žiline sme sa stretli s otcom, ktorý am už mal vlastný podnájom. Na obedy sme chodievali k jeho kamarátkam. Raz k jednej a potom zase k druhej... Z nášho majetku sa ná nepodarilo zachrániť absolútne nič. Aby som sa uživil, začal som pracovať ako inštalatér. Síce som nemal výučný list, no napriek tomu ma zamestnala jedna firma v Žiline. Majiteľom bol tiež Žid.

V povojnovom období sa obnovil aj chod židovskej obce v meste. Počet členov židovskej komunity však neustále klesal. Otec sa odsťahoval ešte v roku 1945 do Karlových Varov 18. Rozhodol sa tak kvôli svojej kamarátke, pani Katzovej. Ona mala v Karlových Varoch známych, rodinu Kleinman. Otec sem prišiel v domnení, že si tu vezme do prenájmu penzión. V podstate všetci odchádzali do Karlových Varov v domnení, že sa uchytia. Ja som za nimi prišiel začiatkom jari v roku 1946. Býval som s otcom. Napokon vychádzali sme spolu dobre.

Otec sa zamestnal v kúpeľoch. No najprv bol v kyslikárni, kde sa plnili kyslíkové fľaše. Potom sa stal na riaditeľstve ubytovacím referentom. Odtiaľ odišiel aj do dôchodku. Ako dôchodca robil inšpektora na kolonáde. V podstate sa tam prechádzal celý deň od rána do večera a dohliadal na poriadok.

V tom období som sa zoznámil so svojou prvou, dnes už nebohou, manželkou. Za slobodna sa volala Irena Rothová. Narodila sa v roku 1926 v meste Kajdanove na Podkarpatskej Rusi. Kajdanove patrilo do okresu Mukačevo. Pochádzala z pobožnej rodiny, ale ona už nebola po vojne tak pobožná. Po vojne sa vrátila na Podkarpatskú Rus. Zistila, že všetky jej kamarátky, ktoré prežili vojnu, sa rozutekali po svete. Jeden z bratov jej mamičky žil v Karlových Varoch. Zhodou okolností to bol pán Kleinman, ku ktorému moja budúca manželka prišla. Zoznámil som sa s ňou u otcovej kamarátky, pani Katzovej. Prišiel som k nej na večeru a moja budúca manželka tam bola tiež. Pani Katzová a Kleinmanová boli kamarátky. Tak sme sa teda „náhodou“ spoznali. Svadbu sme mali židovskú, pod chupou [Chupa: baldachýn, pod ktorým stojí pár pri svadobnom obrade – pozn. red.], v Karlových Varoch, v roku 1946. To však vtedajšie úrady nepočítali za oficiálny sobáš. Civilný sobáš sme mali na jeseň v roku 1948. Svadbu, židovskú, sme oslavovali u Kleinmanových. Zišlo sa tam približne dvadsať ľudí.

Manželka prežila vojnu v Osvienčime, odtiaľ sa dostala do nejakej továrne a nakoniec vyviazla v Terezíne. Jej rodičia zahynuli v Osvienčime. Okrem rodičov mala ešte dvoch bratov. Obaja vojnu prežili a vysťahovali sa do Izraela. Volali sa Imre Roth a Béla Roth. S Imrem som sa stretol neskôr v Karlových Varoch. Bol tu dva alebo tri krát. Jeho brata som nvidel. Manželka sa s ním stretla niekde v Budapešti. Po smrti mojej manželky som s nimi stratil kontakt. Ale myslím, že už tiež nežijú. Manželka rozprávala maďarsky a jidiš, no a samozrejme česky. Ja hovorím česky a slovensky a dohovorím sa aj maďarsky a nemecky. V našej rodine sa držali po vojne väčšie sviatky. Šábes samotný sme veľmi nedržali, len manželka zo začiatku zapaľovala sviečky, neskôr už ani to nie. Taktiež sa oslavoval pésach. Manželka pripravila pésachovú večeru, polievku s macesovými knedlíčkami.

V Karlových Varoch sa po 2. svetovej vojne obnovil aj chod židovskej obce. Napokon, bolo tu dosť Židov. Časom sa však veľa z nich vysťahovalo. Odišli hlavne do Izraela a Ameriky. Tí, čo tu ostali, sa medzi sebou vždy „hrýzli“. Napokon, ako vo všetkých obciach. Samozrejme, bola tu aj modlitebňa, ktorá už dnes nestojí. Obec mala aj rabína a šamesa. Rabín však emigroval. My sme sa na židovskom živote v meste veľmi nepodieľali. Pár krát do roka sme šli so ženou do modlitebne. Hlavne na Roš hašana a Jom kipur. Chlapci s nami nechodili.

Osobne som vnímal vznik štátu Izrael pozitívne. Dokonca by som nenamietal, keby sme sa tam s manželkou boli vysťahovali. Ona tam bola za totality navštíviť svojich bratov. Myslím, že prvý krát v roku 1965. Hovoril som jej: „Vysťahujme sa.“ Jej odpoveď znela: „Ani za nič. Ja som to tam videla a viem, o čo ide. Ja tam nejdem!“ Jej mladšiemu bratovi, Bélovi, ktorý žil v Ber Sheve, sa celkom darilo. Mal firmu, ktorá vozila piesok na stavby. Starší brat, Imre, žil v Nathanyi. Prevádzkoval obchod s nábytkom. Občas skrachoval, potom sa postavil na nohy a zase dookola. Obaja jej bratia si založili vlastné rodiny. Čo sa náboženstva týka, ani jeden z nich nebol pobožný.

Irenka pracovala ako krajčírka. Dlhé roky šlila uniformy a medzitým aj doma známym. Proste šila stále. Po príchode do Karlových Varov som istý čas pracoval ako údržbár pre podnik Československé hotely. Chodil som po hoteloch spravovať batérie a podobné veci. No a potom som sa dostal, do funkcie tajomníka okresu pre kultúru KSČ 19. Členom strany som bol od roku 1945. Napriek tomu, že som tam vstúpil s otcom, vravieval mi: „Ty nebudeš nikdy komunista.“ Hovoril mi to preto, lebo ja som komunistom nikdy neveril. Postupne začali Slánskeho procesy 20. Mňa sa však v podstate vôbec nedotkli.

Udalosti v roku 1968 21 som vnímal pozitívne. Pracoval som vtedy v národnom podniku a bol som predsedom odborovej závodnej rady. V podstate v roku 1968 sa v Karlových Varoch konala konferencia a smerovaní strany. Na tej konferenii vystúpili niektorí členovia okresu s novým spôsobom zmýšlania a sprdli okresného tajomníka komunistickej strany. Ja som bol vtedy vo volebnej komusii a na už sme stihli zvoliť nových ľudí do funkcií v strane, čo mi neskôr samozrejme priťažilo. Ja som však veril, že konám správne. Napokon mi vytkli, moju účasť na danej konferencii. Dospelo to až k tomu, že v roku 1970 ma vykopli zo strany 22. Predtým ma navštívili páni z ŠtB. Povedali mi, že nič odomňa nechcú, len aby som... Ja som im povedal, že nebudem nikoho udávať. Ako predseda závodnej ady som sa vždy snažil, aby bolo všetko spravodlivé a toho som sa aj držal. Neskôr som sa zamestnal ako technik u pozemných stavieb. Jazdil som po stavbách v okolí, napríklad Praha, Chomutov, Cheb, Aš, proste celý región. Veľa voľného času nebolo.

V Karlových Varoch sme zo začiatku bývali v malom studenom, vlhkom, prízemnom byte. Bolo to začiatkom 50. rokov 20. storočia. Napokon sa nám narodili dvaja synovia. Milan v roku 1953 a Roman v roku 1956. Synov sme sa snažili vychovať, ako slušných ľudí. Obriezku nemali, žena to po skúsenostiach z minulost nedovolila. Odvolávala sa na to, že im nechce pokaziť život... Samozrejme, že sme pred nimi ich pôvod netajili a vedeli o všetkom.

Časom sme dostali aj nový, krásny slnečný byt na Víťaznej ulici. Chodievali sme spolu aj na dovolenky. Na západ sa vtedy nedalo. Človek na to nedostal povolenie. Chodievali sme ako rodina do Bulharska. Manželka mala veľa kamarátok a ja som mal tiež jedného kolegu z práce, s ktorým som si rozumel. Trávili sme spolu veľa času aj mimo práce. Stretávali sme sa u nás, alebo u nich. Žiaľ, aj on už zomrel. Tiež sme s manželkou a deťmi jazdili na rôzne dovolenky pod stan. Irenka chodievala aj do kúpeľov. Hlavne do Františkových Lázní a do okolia Písku. Ja som ju tam samozrejme vždy odniesol a potom prišiel pre ňu, takže to som z tých kúpeľov akurát tak mal.

Môj otec sa po vojne ešte tiež oženil. Za manželku si vzal ženu menom Eda Kleinová. Pochádzala z Podkarpatskej Rusi. Edina sestra s manželom bývali v Prahe. Rozhodli sa, že v štvorici si kúpia v Prahe dom. Otec s manželkou obývali poschodie a jeho švagor s manželkou bývali dole. Samozrejme, zvykli sme ich navštevovať, tak dva-trikrát do roka. Otec zomrel v Prahe v roku 1978. Jeho druhá manželka tiež, približne desať rokov po otcovej smrti.

Irenka dostala začiatkom 90. rokov 20. storočia mŕtvicu. Ostala ochrnutá na pol tela. K tomu všetkému sa prieplietol zápaľ pľúc. Chorobe podľahla v roku 1994. Pochovali sme ju na židovskom cintoríne v Karlových Varoch. Medzitým dospeli aj naši synovia. Milan žije v obci Tachov. Je to približne šesťdesiat kilometrov od Karlových Varov. Vyučil sa ako elektromontér. V Tachove sa však v začiatkoch zamestnal ako krmič dobytka, pretože mu pridelili byt, za podmienok, že sa tam zamestná. Roman vyštudoval vysokú školu stavebnú v Prahe. Po štúdiách ostal žiť v Karlových Varoch. Kanceláriu má hneď vedľa židovskej obce. Projektuje stavby a vodí sa mu celkom dobre. Nikdy sa však neoženil. V kancelárii trávi celé týždne, aj víkendy a domov chodí večer o desiatej. Milan si vzal za manželku nežidovské dievča a vyženil si aj syna. Spolu sa im narodil ďalší chlapec. Obe ich deti sú už však dospelé.

Približne päť rokov dozadu som bol navštíviť Izrael. Bol som na poznávacom zájazde. Život tam bol taký, ako som si predstavoval. Ruch na uliciach, kaviarničky. Cesty sú tam prvotriedne. Mimo mesta boli všetky osvetlené, čo tu asi nenájdete. Hovoril som si, že je to celkom fajn. Čo sa životnej úrovne týka, to neviem. Nebol som tam až tak dlho, aby som to vedel posúdiť. Čo ma prekvapilo? Na šábes som bol akurát v Nathanyi. Čakal som, že v sobotu bude všade kľud. Ráno som vstal, vyšiel na okno a všade zástupy áut. Jazdilo ich toľko, ako vo všedný deň. Plné boli aj pláže a na uliciach neustal ruch.

Na prelome tisícročí som sa spoznal so svojou druhou manželkou, Miluškou. Pracovala v potravinách, kam som chodil nakupovať. Tak sme sa stále na seba usmievali, kým raz za mnou nevybehla, že má dva lístky do divadla. Pýtala sa ma, či by som s ňou nešiel. V tej chvíly som ostal v šoku. Musím povedať, že viac-menej sa mi samozrejme páčila. Odvetil som, že hneď neviem odpovedať, ale zistím, či na ten termín nemám program a ozvem sa. V tom čase som už pôsobil ako predseda židovskej obce v Karlových Varoch. Samozrejme, okamžite som si utekal kúpiť oblek a potom som sa vrátil do obchodu a povedal: „Áno, pôjdem do divadla.“ Dopadlo to tak, že sme sa vzali. Miluška nie je Židovka. Svadbu sme mali civilnú. S mojim synom Romanom sa hneď skamarátia. Milan bol zo začiatku trochu odmeraný, ale potom sa dalo všetko do poriadku. Miluška má z prvého manželstva troch synov a sedem vnúčat. Takže teraz sme celkom veľká rodina. Čo sa sviatkov týka, teraz doma nedržíme nič, pretože ona zrušila aj vianočný stromček, ktorý sme my s predošlou manželkou doma mali. Spočiatku sme spolu zvykli chodievať na kúpalisko, no a teraz väčšinou na záhradu.

Niekoľko rokov som pôsobil v predstavenstve židovskej obce v Karlových Varoch. Istý čas som bol miestopredsedom. Vtedajší predseda obce nespĺňal predstavy ostatných členov. Bol podľa nich arogantný. Napríklad niekomu nechcel dať macesy na Pésach, pretože sa neobjavil na obci dosť často a podobne. Zatvoril cintorín a pre kľúč sa muselo chodiť k nemu. Kľúč však nechcel každému požičať. Proste nebol obľúbený. Napokon na jednej výročnej schôdzi vystúpil pán Gubič, že by sa mala oddeliť náboženská funkcia vedúceho obce a funkcia predsedu obce. Napokon sa odhlasovalo, že bývalý predseda ostane ako duchovný vodca obce a mňa zvolili za predsedu. Bolo to približne pred siedmymi rokmi. Mojou úlohou je starať sa o majetok obce. Náboženské záležitosti majú na starosti rabín Kočí a šames Rubin. Tí majú na starosti náboženskú oblasť. Obec má čím ďalej, tým menej aktívnych členov. Môže ich byť asi tak desať. V predstavenstve je nás sedem, na tých sa dá povedať, že sú ako tak aktívny. Všetkých členov je približne 98. Nie všetci sú priamo z Karlových Varov. Máme členov aj v okolitých obciach a mestách, ako napríklad Sokolov a Jáchymov. Židovská obec má svoju modlitebňu, kde sa každý piatok a v sobotu schádzajú na modlenie. Niekedy nemajú minjan [minjan: modlitebné minimum desiatich mužov vo veku nad trinásť rokov – pozn. red.], sú len piati – šiesti. Ale Karlovy Vary sú lázenským mestom, s množstvom hostí, aj židovskými. Preto nie je ničím výnimočným, že sa tu zíde aj dvadsať chlapov. Niektorí z kúpeľných hostí, ktorí tu už boli viac-krát, automaticky prídu aj do modlitebne. Rovnako držíme aj väčšie sviatky. Na sukot sa na dvore budovy obce stavia aj suka.

Glosář:

1 Neolog Jewry: Following a Congress in 1868/69 in Budapest, where the Jewish community was supposed to discuss several issues on which the opinion of the traditionalists and the modernizers differed and which aimed at uniting Hungarian Jews, Hungarian Jewry was officially split into to (later three) communities, which all built up their own national community network. The Neologs were the modernizers, who opposed the Orthodox on various questions. The third group, the sop-called Status Quo Ante advocated that the Jewish community was maintained the same as before the 1868/69 Congress.

2 Great depression

At the end of October 1929, there were worrying signs on the New York Stock Exchange in the securities market. On the 24th of October ('Black Thursday'), people began selling off stocks in a panic from the price drops of the previous days - the number of shares usually sold in a half year exchanged hands in one hour. The banks could not supply the amount of liquid assets required, so people didn't receive money from their sales. Five days later, on 'Black Tuesday', 16.4 million shares were put up for sale, prices dropped steeply, and the hoarded properties suddenly became worthless. The collapse of the Stock Exchange was followed by economic crisis. Banks called in their outstanding loans, causing immediate closings of factories and businesses, leading to higher unemployment, and a decline in the standard of living. By January of 1930, the American money market got back on it's feet, but during this year newer bank crises unfolded: in one month, 325 banks went under. Toward the end of 1930, the crisis spread to Europe: in May of 1931, the Viennese Creditanstalt collapsed (and with it's recall of outstanding loans, took Austrian heavy industry with it). In July, a bank crisis erupted in Germany, by September in England, as well. In Germany, in 1931, more than 19,000 firms closed down. Though in France the banking system withstood the confusion, industrial production and volume of exports tapered off seriously. The agricultural countries of Central Europe were primarily shaken up by the decrease of export revenues, which was followed by a serious agricultural crisis. Romanian export revenues dropped by 73 percent, Poland's by 56 percent. In 1933 in Hungary, debts in the agricultural sphere reached 2.2 billion Pengoes. Compared to the industrial production of 1929, it fell 76 percent in 1932 and 88 percent in 1933. Agricultural unemployment levels, already causing serious concerns, swelled immensely to levels, estimated at the time to be in the hundreds of thousands. In industry the scale of unemployment was 30 percent (about 250,000 people).3 Orthodox communities

The traditionalist Jewish communities founded their own Orthodox organizations after the Universal Meeting in 1868-1869.They organized their life according to Judaist principles and opposed to assimilative aspirations. The community leaders were the rabbis. The statute of their communities was sanctioned by the king in 1871. In the western part of Hungary the communities of the German and Slovakian immigrants’ descendants were formed according to the Western Orthodox principles. At the same time in the East, among the Jews of Galician origins the ‘eastern’ type of Orthodoxy was formed; there the Hassidism prevailed.4 Kashrut in eating habits

kashrut means ritual behavior. A term indicating the religious validity of some object or article according to Jewish law, mainly in the case of foodstuffs. Biblical law dictates which living creatures are allowed to be eaten. The use of blood is strictly forbidden. The method of slaughter is prescribed, the so-called shechitah. The main rule of kashrut is the prohibition of eating dairy and meat products at the same time, even when they weren’t cooked together. The time interval between eating foods differs. On the territory of Slovakia six hours must pass between the eating of a meat and dairy product. In the opposite case, when a dairy product is eaten first and then a meat product, the time interval is different. In some Jewish communities it is sufficient to wash out one’s mouth with water. The longest time interval was three hours – for example in Orthodox communities in Southwestern Slovakia.5 People’s and Public schools in Czechoslovakia

In the 18th century the state intervened in the evolution of schools – in 1877 Empress Maria Theresa issued the Ratio Educationis decree, which reformed all levels of education. After the passing of a law regarding six years of compulsory school attendance in 1868, people’s schools were fundamentally changed, and could now also be secular. During the First Czechoslovak Republic, the Small School Law of 1922 increased compulsory school attendance to eight years. The lower grades of people’s schools were public schools (four years) and the higher grades were council schools. A council school was a general education school for youth between the ages of 10 and 15. Council schools were created in the last quarter of the 19th century as having 4 years, and were usually state-run. Their curriculum was dominated by natural sciences with a practical orientation towards trade and business. During the First Czechoslovak Republic they became 3-year with a 1-year course. After 1945 their curriculum was merged with that of lower gymnasium. After 1948 they disappeared, because all schools were nationalized.6 Hlinka-Guards: Military group under the leadership of the radical wing of the Slovakian Popular Party. The radicals claimed an independent Slovakia and a fascist political and public life. The Hlinka-Guards deported brutally, and without German help, 58,000 (according to other sources 68,000) Slovak Jews between March and October 1942.

7 Czechs in Slovakia from 1938–1945

The rise of Fascism in Europe also had its impact on the fate of Czechs living in Slovakia. The Vienna Arbitration of 1938 had as its consequence the loss of southern Slovakia to Hungary, as a result of which the number of Czechs living in Slovakia declined. A Slovak census held on 31st December 1938 listed 77,488 persons of Czech nationality, a majority of which did not have Slovak residential status. During the period of Slovak autonomy (1938-1939) a government decree was in effect, on the basis of which 9,000 Czech civil servants were let go. The situation of the Czech population grew even worse after the creation of the Slovak State (1939-1945), when these people had the status of foreigners. As a result, by 1943 there were only 31,451 Czechs left in Slovakia.8 Slovak Uprising

At Christmas 1943 the Slovak National Council was formed, consisting of various oppositional groups (communists, social democrats, agrarians etc.). Their aim was to fight the Slovak fascist state. The uprising broke out in Banska Bystrica, central Slovakia, on 20th August 1944. On 18th October the Germans launched an offensive. A large part of the regular Slovak army joined the uprising and the Soviet Army also joined in. Nevertheless the Germans put down the riot and occupied Banska Bystrica on 27th October, but weren’t able to stop the partisan activities. As the Soviet army was drawing closer many of the Slovak partisans joined them in Eastern Slovakia under either Soviet or Slovak command.9 Deportation of Jews from the Slovak State

The size of the Jewish community in the Slovak State in 1939 was around 89,000 residents (according to the 1930 census – it was around 135,000 residents), while after the I. Vienna Arbitration in November 1938, around 40,000 Jews were on the territory gained by Hungary. At a government session on 24th March 1942, the Minister of the Interior, A. Mach, presented a proposed law regarding the expulsion of Jews. From March 1942 to October 1942, 58 transports left Slovakia, and 57,628 people (2/3 of the Jewish population) were deported. The deportees, according to a constitutional law regarding the divestment of state citizenship, they could take with them only 50 kg of precisely specified personal property. The Slovak government paid Nazi Germany a “settlement” subsidy, 500 RM (around 5,000 Sk in the currency of the time) for each person. Constitutional law legalized deportations. After the deportations, not even 20,000 Jews remained in Slovakia. In the fall of 1944 – after the arrival of the Nazi army on the territory of Slovakia, which suppressed the Slovak National Uprising – deportations were renewed. This time the Slovak side fully left their realization to Nazi Germany. In the second phase of 1944-1945, 13,500 Jews were deported from Slovakia, with about 1000 Jewish persons being executed directly on Slovak territory. About 10,000 Jewish citizens were saved thanks to the help of the Slovak populace.Niznansky, Eduard: Zidovska komunita na Slovensku 1939-1945