Faina Sandler

Faina Sandler

Chernovtsy

Ukraine

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of interview: June 2002

According to the family legend our ancestors settled down in Kopyl during the Napoleonic War of 1812. My great-grandmother was a canteen keeper in Napoleon's army and came to Minsk with the army provision transport. Military life turned out to be hard for her. She quit the army and married a local merchant, a Jew. They moved to Kopyl. They opened a small store there and got their own house. They also had children. Since then our family lived in Kopyl.

Kopyl was a small town far away from the railroad. I remember that when my mother, Golda Sandler [nee Abramovich], wanted to visit my father's sister Elena in Minsk the only way of transport was a horse- driven cart. Jews constituted almost half of the population of this town; there were several thousand of them. There was a synagogue in the main square and a cheder right next to it. There was an Orthodox Christian church there as well. The closeness bothered neither the Jewish nor the Belarus population. There were several synagogues in Kopyl, but I can't remember how many exactly. The one in the central square was the biggest - it was a choir synagogue. There was also a city market in this same square. Kopyl was located within quite some distance from other settlements and people sold their products in exchange for other services.

My grandfather on my father's side, Avrom-Ber Sandler, was born in 1871. He was a carpenter. My grandmother was a housewife, which was a usual thing in Jewish families. I don't remember her name; she was just 'Granny' for me. I don't know what kind of family she came from. I only know that she came from Kopyl, too. There were many children in the family. They had two sons and a daughter besides my father. The oldest was Elena, born in 1894, then came Grigory in 1895, and my father, Semyon followed in 1897. Peisah, the last one, was born in 1899. The family wasn't wealthy. My grandmother could hardly get sufficient food and clothing for the family. Except for my grandfather, who was busy in his shop from morning till night, everybody else was helping my grandmother to grow vegetables in her vegetable garden. We mainly grew potatoes, and they saved the family from starving. My grandmother also had a few chickens and a goat.

They lived in a small, miserable house. It had a thatched roof and the goat often jumped onto the roof to eat some of it. They lived a very modest life. My grandmother and grandfather didn't go to the synagogue very often. My father said they prayed at home. They celebrated Jewish holidays in the family, and that's probably all they did. They didn't follow the kashrut. Their children studied in cheder and finished lower secondary school in town. They spoke Yiddish.

My father's brothers Grigory and Peisah moved to Minsk in the early 1930s. Both of them were apprentices to a carpenter at a plant. They married Jewish women. Grigory had two sons, and Peisah had a son and a daughter. Both brothers were on the front. Peisah's family was killed by the fascists in Kopyl on the first day of the war. He got married again after the war and had a son with his second wife. Both brothers were on the front After the war the two they brothers returned to Minsk and stayed there till the end of their lives. Grigory died in the late 1970s and Peisah died in 1984.

My father's sister Elena married a Russian man. She took her husband's last name, Ivleva. He was a high official in the NKVD 1. They lived in Minsk. Elena used to visit us with her husband. They came by car, which was rare at that time. They had a son and a daughter. Elena was a housewife. In 1937 Elena's husband was arrested and shot [during the so-called Great Terror] 2. Fortunately nothing happened to Elena and her children. She attended an accounting course and worked as an accountant at a plant. After Stalin's death in the 1950s Elena's husband was rehabilitated 3. During the war Elena was in the ghetto in Minsk. She managed to escape from there and got into the partisan unit where she stayed until the end of the war. After the war she lived in Minsk with her children. She died there in 1978.

The rules in my father's family weren't as strict as in other Jewish families. All the children were atheists. That's all I can remember. I was very young back then and my father didn't like to talk about his childhood.

I knew my mother's family much better. We lived in the same house with my mother's parents before the evacuation. My grandfather on my mother's side, Avrom-Yankev Abramovich, was born in Kopyl in 1869. He was a religious man, which wasn't surprising because he was a rabbi in Kopyl. He was a respectable man. People often addressed him to ask his advice. Visitors were very often waiting for him at the gate early in the morning.

My grandfather died when I was 4, but I know much about him from what my mother told me. In addition, I still have some memories of my own. My brother was often surprised to hear me talking about events from our childhood. He said that I was too young to remember such things.

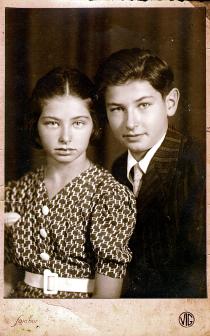

My grandfather always wore a long black jacket and a black hat no matter what the weather was like. He had a nicely trimmed beard. My grandmother, grandfather and their children didn't look like Jews. They were tall, fair-haired and had gray eyes. My father and my brother Mihail were also gray-eyed blondes. I'm the only one in the family with black hair and dark eyes. I suffered much in my childhood because I thought I didn't belong to them.

My grandfather was the grandnephew of Mendele Moykher Sforim 4, a well-known Jewish writer. That was his pseudonym. His real name was Shalom Jacob Abramovits. Mendele was born in Kopyl in 1835. He was the brother of my grandfather's father. His family was poor. Mendele met somebody who helped him to learn languages, history, philosophy and literature. He moved to Berdichev and then to Odessa. He lived in Odessa from the 1880s until his death in 1917. My parents told me that all documents, photos and portraits - everything related to his biography - were kept in my grandfather's house. I also know that a Museum of Jewish Culture was opened in Minsk before the war. They addressed my grandfather with the request to give all these things to the museum, but he refused. During the war the family perished, and the house was destroyed along with all the relics.

I have dim memories of my grandfather but very clear memories of my grandmother, Genia Abramovich. She looked after me and was very nice and kind. My grandmother was only one year younger than my grandfather, but she looked much younger. She was born in Kopyl in 1870. She often told me about her childhood. Unfortunately, I can hardly remember those stories. I only remember one story about her mother, who was a well-known healer. She cured people with herbs. My grandmother told me that her mother was very upset that her daughters didn't want to follow into her footsteps. My great-grandmother died taking her secrets into the grave with her. I was very sorry that she didn't live until I was born. I would have listened to her every word. I don't know my grandmother's maiden name or anything about her meeting with my grandfather and their wedding. Only, knowing my grandfather, I'm sure that they had a traditional Jewish wedding. They spoke Yiddish in the family.

My grandparents lived in a big spacious house with five rooms and a big kitchen. There was a big yard and a flower garden, as well as a shed, where they kept a cow, and a vegetable garden. They were quite wealthy, I believe. My grandmother did all the housework herself.

They had many children. I only know the names of the two, who left for America in the 1920s: one of them was called Zelda and her family name was Diamant. Zelda's husband was a farmer. Their daughter, Mildred, was born in America. They were successful. The other one who left for America was called Meyer. He was an engineer. He got married. We received a letter from Zelda after the war. She told us about her life and her daughter and asked us if we needed any help. She also sent pictures of her and her brother Meyer. To keep in touch with relatives abroad was very dangerous at the time. My brother was working at the military plant at that time, had a special sensitive work permit and such facts could have ruined his career. My Mama wrote one single letter to Zelda asking her to stop writing us. Much later, in the 1990s, I was trying to find my cousin, Mildred, but I failed.

Another one of my mother's brothers lived in Belostok, Poland. Mama said that he perished in Auschwitz during the occupation of Poland.

One of my mother's brother and two sisters lived in Kopyl. I can't remember their names. They had children and we used to play together. They visited us with their families. On Pesach the whole family got together. They didn't evacuate during the war and perished in the ghetto. The only date imprinted on my memory and related to my mother's family is their date of death: 1941.

My grandparents strictly observed Jewish traditions. On Friday my grandmother lit the candles and cooked dinner for Saturday. She baked deliciously smelling challah. My grandfather went to the synagogue every day; my grandmother went on Saturdays. They strictly followed the kashrut. They celebrated Jewish holidays. I remember preparations for Pesach. The house was always clean, but before Pesach it had to be all shiny. They took fancy dishes from the attic and washed them. I remember those dishes. I especially remember the bright turquoise salt- cellar. I was mesmerized by it. I remember big bags of matzah that were brought from the bakery at the synagogue. I also remember the big table covered with white cloth and family gatherings on Pesach. My grandmother and my mother spent a lot of time in the kitchen before Pesach to have all the required food on the table on Pesach. I can't remember all the dishes. We, kids, couldn't wait until they were over with chicken broth, stuffed fish, stuffed chicken neck, etc. to take to my grandmother's strudels with jam, nuts and raisins that melted in the mouth. We preferred these to all other Pesach dishes.

My grandfather was reading the prayer, but I don't remember it well. We, children, did not have to be present at this time. After my grandfather died there was no more praying in our house. I remember the very delicious hamantashen with poppy seeds that my grandmother and mother baked at Purim. Chanukkah was memorable for the Chanukkah gelt that we were given. My brother took away the bigger part of my money, but I loved to go to the store and buy two lollypops and some sunflower seeds with my own money - just like an adult. I loved shopping, and the shopping assistant didn't fail to play along with me. He asked me how I liked what I had bought the previous year and invited me to come again. On Yiom -Kippur all members of our family, except for my brother, my father and me, were fasting. According to the Jewish tradition children could avoid fasting, and my Papa didn't find it necessary to fast. As I've mentioned already, they weren't nearly as strict about observing traditions in my father's family, as they were in my mother's. Mama suffered a lot because she couldn't observe all Jewish laws and traditions. She never ate pork or sausage - it was the result of her upbringing. My father didn't care about such things. It was of no significance to him.

I was surprised that my father's and my mother's families were so close because they were so different. They had different standards of life, and the level of education and their attitude toward religion and traditions were also so different. Theirs wasn't just a relationship of two families whose children got married. It was true friendship. Many years later I found out the reason for it. Both my grandmothers had their children almost at the same time. They lived near one another. Grandmother Genia didn't have breast milk, and my father's mother was breastfeeding both babies. This means that my mother and father were in a way foster brother and sister. My mother's parents believed that my other grandmother saved their daughter's life. Their gratitude grew into a friendship that lasted a lifetime.

Since Kopyl was located far from the main roads it was safe from pogroms. The local people didn't take part in pogroms, and the gangs from other settlements didn't reach the town. The Revolution of 1917 5 had no impact on the town either. However, my father was on the front during the Civil War 6. My parents got married after he returned. I don't know whether they had a wedding party. They got married in 1925, and my brother Mihail was born in 1928. The newly weds lived with my mother's parents. Mama was a housewife and looked after my brother. My father took a course in accounting and got a job as an accountant at the peat-bog.

I was born in 1934. I got my name after some of my mother's relative who died when she was young. The name Faina is written in my birth certificate, but I was affectionately called Fania at home. My grandfather and grandmother spoke Yiddish. My mother and father spoke both Yiddish and Russian, and I knew both languages because they spoke to me in either one depending on their mood. My brother also spoke fluent Belarus. I found out that I was a Jew in the kindergarten. Although Mama didn't work I still went to the kindergarten. They believed at that time that a child should get used to getting along with other children. I remember that we sang patriotic songs in a choir and learned poems about Lenin and Stalin. Once a commission came and someone of the commission asked about me, and I remember that our teacher told him that I was a Jew. I came home and asked my mother what that meant. She explained it to me. For a long time my favorite stories were the stories from the Bible she was telling me.

There was no acute anti-Semitism before the war. Nationality wasn't even an issue, my parents told me. I don't remember my friends from kindergarten, and therefore I don't know if they were Jews.

My brother went to the 1st grade of a Russian school in 1935. He was a very smart boy and had no problems with his studies. There were Jewish, Russian and Belarus children in class, and the children communicated in three languages. They understood each other well, and there were no nationality issues between them.

1937 was a very hard year for our family. I've already mentioned that Elena's husband was arrested. But that wasn't all. In the same year Grandfather Avrom-Yankev died. He had prostate adenoma resulting in uremia. He died after suffering a lot in July 1937. We buried him in the Jewish part of the cemetery. We didn't observe any Jewish rituals. Nobody observed any traditions in those years - they weren't popular any more and not appreciated by the authorities. Only his closest friends were at the funeral.

My father told me that there was a time in 1937 when he was very afraid that he would be arrested. I don't know why he was afraid, but there was no way of asking 'why' at that time. It was a small town and some acquaintance from the NKVD mentioned to my father that it would be better for him to hide away for some time. Many of my father's friends were arrested, sentenced or disappeared in prison camps. My father was away from home for about a year. The repression affected even distant locations, although there was no industry apart from the peat shop.

I can't say anything about Hitler coming to power, but Mama told me after the war that it seemed to them an internal affair of Germany, like something that would never have anything to do with them. My parents were concerned when Germany attacked Poland because my mother's brother lived in Poland. After Western Belarus joined the USSR in 1938 my mother established contacts with her brother and his family. [Editor's note: Soviet troops moved into Western Belarus in September 1939, soon after the outbreak of WWII. Arrests started and masses of people were deported to Soviet labor camps.] They all hoped that it would be the beginning of a peaceful life. After the USSR entered into the Non-Aggression Agreement with Germany [the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact] 7 people stopped worrying.

I remember the beginning of the war. It wasn't the Sunday22nd June 1941 for Kopyl. The war for us began earlier, in the night of 21st June. Everybody was asleep, and it was dark when all of a sudden the silence was broken by cannon-balls and flashes and a horrible roar. The buildings were on fire at once. My father's younger brother, Peisah, ran into our house. He had come from Minsk with his family to visit his relatives. A bomb hit his parents' house killing everyone inside. Peisah was alive because he was sleeping in the garden because of the heat. He told us to get ready to leave. There was a cart in the yard. My parents were trying to convince Granny Genia to leave with us. Mama was crying and begging her to get ready. But my grandmother refused flatly. She was saying that it wouldn't be for long and that there was nothing to fear. She remembered the Germans from World War I and believed there was nothing to fear about them. Regretfully, many people who survived World War I were thinking that way. Nobody expected it would turn into such a calamity. My grandmother perished in Kopyl like all other Jews. They were shot and buried in a pit during the first days of the occupation.

We ran away. We were moving at nighttime and hiding in the woods. There were five of us: Mama, Papa, Peisah, my brother and I. We happened to be close to German capture twice. I remember we stopped to eat and rest, and I went to pick some flowers. I remember that all of a sudden a German soldier with an automatic gun rose from the grass in front of me. I screamed and don't remember what happened then. I also remember another night when we came to the road leading to the railway station. German motorcycles and cars were there. We were cut off but we managed to get through. We reached Blykhov railway station and got on a flatcar of a train - there was no other opportunity to leave. When we had just boarded the train the bombing began. All adults ran away leaving me behind in their panic, and I was sitting there alone throughout the raid.

I remember I was crying throughout our trip because I was hungry, but we didn't have any food with us. A military train was passing by and a soldier gave me some bread. There were many people on that flatcar. Nobody knew where we were going to. We stopped in Kirsanov, Tambov region. My father went to the recruitment office and left for the front. The front was moving closer, and we had to leave. We evacuated to Kazakhstan and then to Kyrgyzstan. In Kazakhstan we stayed in a village in the desert. Water was more precious than gold there. People shared their water and bread with us. In winter we arrived in Frunze, Kyrgyzstan. We met our acquaintances there, and they helped us to find a place to live. It was a clay shed for cattle. It had small windows right beneath the ceiling, and the roof was supported by tree trunks. There were many trunks, and Mama jokingly said that we were living in the Column Hall of the House of Unions. We slept on plank beds and stayed in this hut until the end of the war.

My father found us via the evacuation search agency in Buguruslan. He had been wounded in the battles near Stalingrad and sent to Kopeysk in the Ural. He developed gangrene in the hospital where he was staying and his leg had to be amputated. It's a miracle that my father survived. Later he had another surgery. Then he somehow managed to be transferred to the hospital in Frunze. There weren't enough nurses in the hospital. Mama went to the hospital to look after Papa. He was released in 1943 with his leg amputated up to his hip joint, and he walked with crutches for the rest of his life.

My brother and I went to school. I went to the 1st grade in Kazakhstan and then stopped my studies. So, in Frunze I went to the 1st grade again. I could read ever since I had turned 3, so I didn't have any problem. We didn't have any textbooks. We had notebooks made from newspapers and were writing between the lines. There were mainly evacuated children in the class as well as our teacher, Margarita Nikolaevna.

The local people treated us nicely and supported us. There were Koreans, Chechens and Tatars in our neighborhood. Many of them had been deported there. People were living in some kind of holes, but they got along well and had no conflicts.

Mama got a sewing machine at the market. I still have it. Mama could sew and saved us from starving to death that way. I don't know what she exchanged that sewing machine for. We didn't have anything. I remember the dress Mama had. Nurses in hospital where my father was were throwing away used bandages. Mama picked them up, washed and colored them with onion peel and made a dress out of them.

During the evacuation Mama and I fell ill with jaundice. The hospital was overcrowded, so we were taking the treatment at home. When I grew older I heard about the 'method' we used back then and was horrified: we had to swallow a few lice. There was no lack of that 'medication' back then. However strange it may sound, swallowing lice helped. Mama had liver problems for the rest of her life, though.

I remember people coming into our hut to beg for some food. They were so swollen up from hunger that they looked like balloons. Once a man wanted to change salt for some food - and there were lice in this salt. Many people starved to death or died of diseases.

When my father returned he received his invalidity pension. We managed somehow, but it was impossible to buy anything for money. Mama saved us with her sewing. Sometimes she made flat bread from black sticky flour. Since that time I hate melons by the way. I can't even stand their smell. Melon was the only thing there in sufficient quantity, and our basic food was dried apricots and melons. Now theses things are delicacies.

My brother and I grew out of our clothes. Mama was altering them and we managed to have clothing that way.

The climate in Frunze is continental, and winters are cold. We had a Burzhuika stove in the middle of the room. It served for cooking and heating. We, kids, were constantly looking for chips of wood for this stove. We weren't under the risk of violent death, and we weren't living behind barbed wire, but to call it life - oh, Lord, no. We were constantly facing starvation or diseases. There were also cases of violent death. My mother's friend was in evacuation in Frunze with her little daughters. One was a year old and the other one about 3. Well, their mother went to the market to get some food in exchange for a few clothes and was murdered on her way for these rags. A family from Moscow adopted her two girls. Another Jewish family we made good friends with and went to Chernovtsy with after the war, adopted a Jewish boy. I also remember another story: the mother of two boys died. A Russian family adopted the older one, Izia, who was the same age as I. At that time nobody cared about nationality; those kids were orphans that needed a family. The younger brother was a very sickly boy. My mother's friend, Polina, was looking after him. He began to call her Mama, and she couldn't part with him when he got better. He never knew that she wasn't his real mother.

We listened to the radio for news about the war. Sometimes we had newspapers. Newspapers were valuable to us, because we made notebooks from them by tearing them to individual pages and putting those together.

My brother finished school in Frunze in 1944 when he was 16. He passed his exams for the 10th grade. He wanted to learn a profession and go to work. At 16 he entered the Institute of Electric Engineering in Leningrad and finished his 1st year while we were in Frunze.

I remember the dawn of 9th May 1945. Our neighbor banged on our door shouting, 'The war is over! The war is over!' People were rejoicing, crying and kissing each other. I don't know who was the 1st to know, but we heard about it at dawn. That whole day people hugged each other and danced.

We knew what had happened to our relatives because Belarus was already liberated. We knew that none of them was alive. Mama firmly said firmly, 'I shall not return to the ashes of our home. I just can't'. We were thinking of where to go. Our neighbor lived in Chernovtsy before the war. He told us a lot about Bukovina. He said that his friends had told him that the town wasn't destroyed. He convinced us to go there. We arrived on 3rd September 1945.

The institute where my brother studied was to return to Leningrad. We were considering of letting him go there, but it was difficult. There was no money or clothes. We decided that he should be with us. In Chernovtsy he entered the chemical department of the university. Mama made him a jacket from Papa's uniform coat, and he wore that one until he finished university.

It was easy to find a place to live in Chernovtsy. There were many empty apartments. The town had been liberated in 1944, and many families were leaving for Romania. We moved into a large three-bedroom apartment along with another family. We thought it would be easier to maintain and heat the apartment. People weren't eager to have separate apartments then. The town was intact, except for three buildings. There had been Romanian units in this town, and they were careful to leave the town in good condition because they were hoping that once it would be given back to them. So, we didn't have a problem with getting a decent apartment. The problem was clothing, food and heating.

My father got a job as the chief accountant of the Social Provisions Department. Mama made him a jacket, and he wore it to work. Mama also made me a jacket from a blanket. Our first years after the war were difficult, but we were happy that the war was over. Mama fell ill with bronchitis which resulted in pneumonia, which again developed into bronchial asthma. My father was an invalid. His salary and little pension was all our income. Mama helped to provide for the family with her sewing. But we were glad we survived. We enjoyed having boiled potatoes, cucumbers, plums and apples.

I went to the 4th grade of the Russian school for girls in 1945. There were two schools for boys and two for girls. There were 30 girls in my class. We didn't have enough textbooks and used some Ukrainian textbooks. It was difficult at first because I didn't know Ukrainian. But I picked it up soon and managed.

There were many Jewish children at school. There was also a Jewish school, but it was too far away from our home. During the campaign against 'cosmopolitans' 8 it was closed, and the girls from this school came to our class. My Russian classmate told me recently that she learned all Jewish traditions from another classmate from that Jewish school. There was no anti-Semitism at school or elsewhere. Chernovtsy had always been a very tolerant town. Yiddish was heard in the streets. Peasants or janitors could speak Yiddish, German and Romanian.

In the 4th grade I became a pioneer. It was a routinely procedure at school. We celebrated all Soviet holidays at school: 1st May and 7th November [October Revolution Day] 9. Nothing changed in my life. In the morning teachers and children went to the parade. At home we didn't celebrate Soviet holidays. In the evening there was a concert at school for the children and their parents. Firstly, we couldn't afford to celebrate and, secondly, my mother didn't acknowledge those holidays. My brother and I didn't mind having a celebration, but we understood that we couldn't ask Mama about it. MyY parents didn't go to the synagogue in Chernovtsy. My father didn't care about it, and my mother couldn't stay in a crowd of people because she had asthmatic fits. Mama only celebrated Pesach until her last days. She never had enough money and saved for a whole year to have us enjoy the food at Easter. We bought some matzah at the synagogue. We only ate matzah on the first and last day of the holidays and managed without bread on the rest of the days. Besides Pesach we also celebrated New Year's and birthdays.

We lived near the Jewish theater. The leading actors of this theater lived in our house and the neighboring buildings. My friend and I went to their performances. By the way, this was the Jewish theater from Kiev that moved to Chernovtsy because the building of the theater in Kiev had been destroyed by bombing. They moved temporarily, as they said, until the building in Kiev was restored. In the end they stayed in Chernovtsy for good. In 1948, during the campaign against 'cosmopolitans', the theater was closed. I went to see almost all their performances, although I could hardly afford it. Besides going to the theater I read a lot. Our whole family read a lot. We had a huge collection of books that had been left by the previous owners of the apartment. There were books in Yiddish, Russian and French. Reading has always been my hobby.

I became a Komsomol 10 member in the 10th grade. I have never been involved in politics or social activities. I didn't like meetings or social activities and avoided them as much as I could. In the 10th grade my teacher told me that I wouldn't receive a medal or be able to enter university if I didn't become a Komsomol member. I gave in and submitted my application to the Komsomol.

I remember how happy my parents were when they heard about the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. Even my father, who usually kept his emotions to himself, began to smile when he talked about it. It was a moral support for them to know that their 'drifting' people had finally found their motherland. I was too small to understand things back then.

I remember 1948, the campaign against 'cosmopolitans', very well. We had a book about Jews, published in Romania. I remember Papa saying that we had to burn it. I was hysterical about having to burn such a book, but he said I didn't understand things and insisted on our doing this. It was dangerous to have such books at home - it was a reason for being accused of chauvinism. My family and my friends' families didn't suffer, but it was a hard time. One couldn't even talk to his acquaintance because nobody knew the consequences. The Jewish school and theater were closed.

My brother graduated in 1949 and got a job assignment in Tashkent. Thanks to him I managed to finish school. My parents wanted me to go to technical school after the 7th grade, get a profession and go to work. They were very short of money. But my brother insisted that I continued my studies if I wanted. His salary was 800 rubles per month, and he sent us 500 rubles. Perhaps, this was one of the reasons why my brother stayed single. I finished ten years at school and studied at university with my brother's support.

I faced anti-Semitism at school for the first time. It didn't come from my classmates, but from their parents. The parents of two girls in our class worked at the NKVD. They were spoiled girls and didn't study well. The mother of one of them came to school and screamed that Jewish girls had the highest grades in the Russian language when her daughter only had a '2' or '3'. She was asking whether it was possible that Jewish girls knew Russian better than a Russian girl. Then I understood what anti-Semitism meant. I had excellent marks in all subjects, and nobody doubted that I was going to receive a gold medal. I passed all 12 final exams with the highest grades, but got a '4' in composition. When I demanded that they showed this composition to me they said that I made no mistakes, but got a lower grade for my handwriting. It was ridiculous. I finished school in 1952 and received a silver medal.

I couldn't go to study in another town. My parents were ill, and I had to be with them. Anti-Semitism on the state level was at its height in Chernovtsy. It was very hard for a Jew to enter a higher educational institution. My silver medal gave me the right to enter university without exams. I decided to study at the Chemistry Department. There were 25 applicants and only five were to be accepted. One of the university assistants was present at our final exams at school, and he helped me to get through. Also, my father went to the rector. He was a veteran and a war invalid. He didn't want to ask for me, but it was the only way out. I was admitted and I was the only Jew in my class.

The Doctors' Plot 11 began when I was a 1st year student. This was a disturbing period, very much like 1937. We were stunned. Everyone realized that it was all schemed. The majority of the population had a nice attitude towards Jews. It was mainly anti-Semitism on the state level. A few years later I had a discussion with a Ukrainian friend of mine. He studied at the Medical Institute. I asked him why Ukrainian people were loyal towards Jews, and he said that they have always been friendly with each other. However, the Russian people, who established the Soviet power in Bukovina and 'liberated' it, weren't appreciated so much.

In 1953 Stalin died. I must have been very naïve. There was something disastrous in his death. Although it was no secret that Stalin was a tyrant we had a weird feeling about how we were going to live without him. My father knew the truth about Stalin and told my brother and me about it. My father witnessed the arrests of 1937 [during the Great Terror] and understood the reason for it. But I couldn't understand what was to happen to us and how life was to continue without Stalin.

I graduated from university in 1957. I had excellent grades in all subjects except for Marxism-Leninism; they gave me a '4' at the exam. There was an assistant professor at the exam - she came from old nobility - and when she saw what grade they were giving me she blushed of indignation. The students I was helping right there at the exams got a '5'. I received a diploma but couldn't find a job.

Whatever vacancies I applied for the response was always that they had already employed someone else. I couldn't find a job for eight months until my brother's friend helped me to get one at the laboratory of a shop. I was paid 45 rubles per month. This seemed a fortune to me. I was happy to have this job, although it wasn't good enough considering I had a university degree. I worked there for 41 years. I faced anti- Semitism at work more than once. They appointed a young inexperienced girl for the position of the chief of the laboratory, although I was the only candidate for this position at that time. In the long run I got the position of an engineer and senior engineer, although I was the first female inventor in Ukraine. I could have been further promoted if I had become a party member, but I didn't want to be one.

I worked in a Jewish team. Our chief and about 90% of the employees were Jews, so my colleagues never expressed any anti-Semitic feelings towards me.

When I began to work in this laboratory I believed it wouldn't be for long. I imagined a different career. I was told by someone that the head of department at Chernovtsy University said once that he would have loved to enlist me for the post-graduate course, but he was afraid they wouldn't have let him do this. Now, after all these years, I think I was very lucky. I worked in a great team with a great erudite boss. I learned a lot from him. I've never liked chemistry though. I do my job appropriately and thoroughly. Speaking about my dream: I would like to work with animals. I love animals, and I know how to approach them. A couple of doves come to my windowsill. I have been friends with them for five years. They eat from my hand. I love cats and dogs, whatever animal it doesn't matter.

In the 1970s Jews began to emigrate to Israel. I remember buying something from a peasant woman at the time, and she asked me why I didn't leave. I said I felt okay where I was. And she said to me, 'Have you read the Bible? You are young and you just don't know that the time has come when God gets all his people together at one location'. Another time I was waiting for a bus. Two Ukrainian women were talking behind me. They were saying with regret that there would be no good doctor or teacher left after all Jews emigrated. People in Chernovtsy say that the town was different before the Jews left.

I never wanted to emigrate to Israel for different reasons. I'm all alone. I have some relatives abroad, but I wouldn't be able to find them. And here I have at least my friends, ex-colleagues and other people that I can socialize with. What would I find in a foreign land? Besides, the climate in Israel is unacceptable for me because I have heart problems. I have thought about it, and I understood that I was going to take my problems with me and have new ones there on top of it. When I was just beginning to think about it my brother was still alive. He worked at the Military Enterprise for many years. In his last years he was head of the shop at the Microelectronics Plant in Sevastopol and had access to sensitive information. Even if he had left his work he would have only been allowed to leave the country after 15-20 years. We were very close. I couldn't imagine leaving without him. My brother died in 1980 when he was still young. My mother died in 1962 and my father in 1978. It's impossible to live alone. I need somebody close. I'm not married, but that's the way things are. I was looking after my parents and lived in the same apartment with them for many years. I couldn't even imagine inviting a man to my home. But perhaps, I just didn't meet my Mr. Right. I would like to visit Israel, this wonderful country. But with my pension I can only dream about it.

Since Ukraine gained its independence the attitude towards Jews has changed dramatically. At first they started talking calmly about Jews on TV, radio and in newspapers. Previously they had even avoided to say the word 'Jew'. Jewish culture is in the process of being restored. Things have undoubtedly improved. Many Jewish newspapers and magazines are published. I don't know how sincere our government is but it tries to be tolerant towards Jews and shows an interest in them.

I read Jewish newspapers and learned about the spiritual heritage of the Jewish people at university. We celebrate Sabbath in the community. I have many friends there. I'm trying to light Sabbath candles at home. I celebrate Jewish holidays at home. What's going on around convinced me finally that there is God. He supports his people. He is there, I know he is.

Glossary