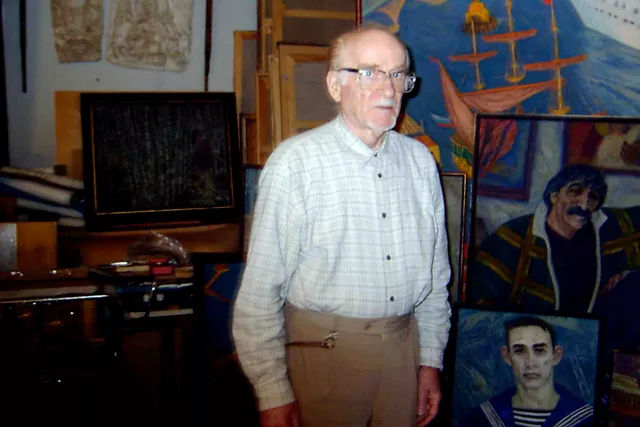

Solomon Epstein

This photograph taken in 2007 shows me in my studio in St. Petersburg.

Unfortunately now I have no photographs taken at the front-line. Therefore here I’d like to tell you about the war. I remember several episodes: they are not heroic, but rather interesting.

Once (in spring) field-kitchens were caught in the mud and our food supplies gave out. Genka suggested going to the neighboring village and earning some food drawing portraits of inhabitants. It was me who had to draw.

At that time I always had clean sheets of paper (I did my best to find them everywhere I could) and a stub of a pencil with me. So Genka and I started towards the village during a lull in the fighting.

The village appeared to be not far from our position: about 1.5 kilometers. We found there a long earth-house and a bench in front of it. An old man was sitting on that bench. We greeted him and sat down beside him. I asked if it was permissible to draw his portrait.

The old man examined us suspiciously 'What for?' I answered that I was an artist and wanted to draw during a lull in the fighting. 'Well, do it, if you wish!' I drew him quickly and the portrait was a good likeness. His wife appeared, sat down next to him, and looked at my drawing. 'Look, it's you! It looks like a photo!'

The old man agreed 'You are quick and skillful!' I handed the drawing over to him. He moved away mistrustfully 'How much is it?' - 'It's free. But if you give us something to eat, we would be grateful. You see, our field-kitchens lagged behind and we have nothing to eat.' The old man took the portrait, looked at his wife and nodded his approval.

She jumped up and some minutes later called us to their earth-house. With great pleasure we ate shchi, potatoes and pickled cucumbers. After that I drew a portrait of the old woman.

Their neighbors came; they wanted to have their portraits, too. I drew quickly. One hour of my work resulted in a small bag of potatoes, a piece of lard, some hard-boiled eggs and onions, a loaf of bread, some salt.

My earned income appeared to be great! We became friends. Genka wanted to carry the bag: 'You worked, and I only chattered!' 'No, you did good public relations for my work!' Nevertheless he took the bag from me and carried it himself.

Our return was triumphal. We made a fire and reheated our meals. We also shared it with soldiers from other platoons... Here I told you about this sort of fighting episodes...

Another day I was appointed to accompany a local peasant mobilized to collect milk from neighboring farms for our hospital. At that time I was already recovering. I had to guard him and took my sub-machine gun with me.

Not to frighten people, I hid my sub-machine gun in his telega under the hay and we started moving slowly and talking peacefully about everything. [Telega is a four-wheel carriage.] He told me that he was a poor man, his farm was situated nearby.

So we went from one farm to another. Sometimes people friendly rolled out big cans of milk and helped us to put them into the telega, the others obeyed gloomily. One peasant served us a hefty meal. By the evening we brought about 20 big cans of milk to the hospital.

We became friends with that peasant. I was sleepy. I got into bed, but jumped up immediately! My sub-machine gun! That peasant had taken it away in his telega. I knew for sure that a soldier who lost his arms was worth death by shooting.

I decided to find that peasant. I had to go through the wood, and it was extremely dangerous, because the wood was full of wood brothers. [Wood brothers was a cumulative name of anti-soviet armed groups on the territory of Baltic Republics.]

I was sure that I would never get back alive. At last, after a long way I came to his farm more dead than alive. My driver came out of his house carrying my sub-machine gun.

I seized it hastily and hung it on my shoulder. The peasant's wife invited me to visit their house, gave me some bacon and apples. See what a prize I found!