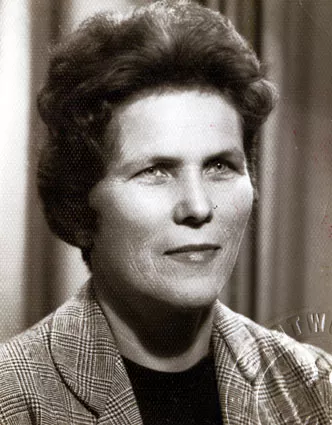

This is my friend Zaba in the 1950s. I think this picture was taken in Warsaw, where she lived after the war. I don’t remember exactly who gave it to me - Zaba or her daughter.

When the war broke out I lived with my family in Warsaw at Leszno Street. My father cut it short and committed suicide, through the window of his sisters’ apartment. That may have been in 1940, before the Ghetto [before October 1940]. My mother and I remained at Leszno until the deportations began, and then we got an apartment at 16 or 18 Mila Street. I wasn't there long, only a few weeks. When things got really bad and Jews were being rounded up, one of my co-workers offered to get me out of the Ghetto. It was September 1942, a few days before the major deportations began. So I got up and left. At first I was in hiding in Warsaw in various apartments. Then I wanted to go back to the Ghetto, and I wrote a letter to my brother. He had been in hiding, but the Germans caught him and sent him to work. He worked outside the Ghetto. When I wrote to him that I want to get out, he wrote back that a woman would come and take care of me.

And indeed, a woman came. She was in mourning. It turned out her father committed suicide by hanging himself. She was my brother's friend, Zaba from Konskowola [around 100 km south-east from Warsaw]. I have no idea where he met her.

So I went to Zaba's, to Konskowola and I actually was very comfortable there. She was a nurse, 6 years older than I was; before the war she took nursing courses in Warsaw. Her mother was Czech, a lovely woman. Zaba's husband was a railway man. They had a daughter Ewa who was 2 or 2-and-a-half when I came. She called me ‘auntie.’ Everybody around must have known I was Jewish, but nobody said anything. Zaba was a brave woman, and her husband was a sissy. She took care of me, she hugged me, she ruled that house so that he didn't have much say, lucky for me… We lived in a brick house next to the railway tracks, by the crossing. When they started deporting the Jews, I could see the boxcars with people in the windows. Once I thought I saw my brother, but I don't know if it was him… And when those trains were going to Majdanek, then Zaba's husband-a kind, polite man-said that one good thing Hitler was doing was what was happening to the Jews. I told Zaba about that, and she said 'Come on, he doesn't know what he is saying.' That was the end of it, but it stayed with me. Anyway, it wasn't good company for me. Zaba's sister-in-law, Hela, a bad one, took an astrakhan fur coat from her Jewish friend and denounced her to the gendarmes. Why didn't she denounce me? When one of Zaba's friends came over I had to spend the whole time under the bed. So it was pretty interesting over there…

When I stayed with Zaba, her brother Czesio came to visit once. But because I was there, he went back to his house for the night. And that night the Germans pulled out all the young people, including him. I had a bad conscience because if he'd stayed the night, instead of me, maybe he would have survived. And he was shot.

I spent two years with Zaba, from 1942 till the end of the war, when Lublin was freed [July 1944], possibly before Warsaw was. When the Russkies came, they wanted to arrest Zaba's other brother, Edward, who was the mayor. People were denouncing him, because apparently he was stealing their cows and produce. To put it short, he was a son-of-a-bitch. When they came to get him he hid somewhere. But the people who he'd rubbed up the wrong way came after him and there was a court case in Lublin after the war. And I was the main witness for the defense. I said in court: 'I can't say anything against Edward, because I am Jewish and this family saved my life.' I did it only for Zaba and her mother, not anybody else from that family. Because of what I said he was released, after having been held for a year and a half.

After the war I helped Zaba-my husband had connections, so he arranged for an apartment in Warsaw and a job at the hospital for Zaba's daughter. After Zaba died, in 1973, her husband wanted me to help him get into the veterans' union. How could I? I didn't have any connections there. So I told him there was this tree campaign. And he got the title of ‘Righteous Among the Nations.’ He accepted it in his and Zaba's name.