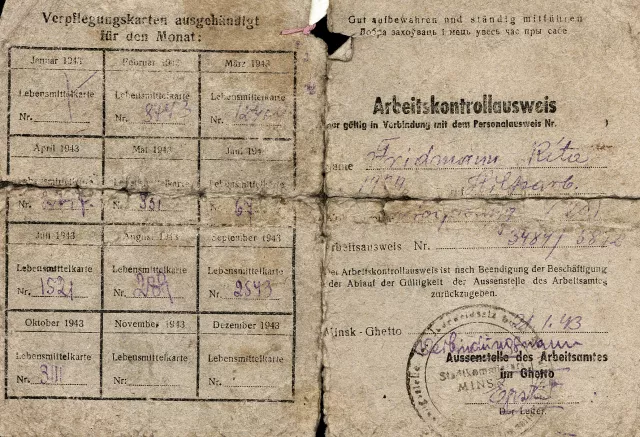

Rita Kazhdan's Worker's ID Card from World War II

This is my Worker's ID Card, the ?Arbeitkontrollausweis?, from the Minsk ghetto, from May 1942, nearly two months after mum's death. On the back a record of the monthly rations of the ghetto prisoners was kept. The ration was one loaf of bread and a few kilograms of potatoes.

After the massacre in March 1942, we moved to the place of Abram Aronovich Levin, the husband of mum's friend - a wonderful man, very decent, in advanced years. He was a pharmacist. In this drugstore there was a so-called malina, a place where one could hide from the fascists. Abram Aronovich himself stayed in the drugstore as the manager, and we edged ourselves into the pharmaceutical cupboard in the next room, where drugs and measuring glasses were kept, through the lower shelf, which could be pulled out; then Levin put the shelf back. This is how we concealed ourselves.

Mum came out and Abram's wife asked her to go home and pick up certain things. As mum was a working person, she had special documents with her. Everybody knew the Germans were catching (and shooting) only unemployed people. We never saw mum again. Then we were informed that she had been taken away with other Jews, and there was a baby in her arms. Mum had a perfect command of German, but apparently there were not only Germans but policemen as well - the traitors, who served for the Germans - so she didn't manage to leave the column. So my brother and I were left without any means of subsistence.

I was like a skeleton covered with skin. But I always had a ruddy and round face. So they didn't pay special attention to me. That's why I could walk away from the crowd that convoyed to work and beg in the streets and in the Russian district. And from time to time I succeeded in taking something into the ghetto for my brother. Once as I was walking out of the ghetto, I came across my classmate who helped get me fixed up in the plant where one could do hard unskilled work. 75 Russian Jews were working at the plant. They were roofers, cleaners, carpenters, and laundrymen. Before the war it had been the machine-tool plant named after Voroshylov, and during the occupation German tanks were repaired here. I was a pin-up, very beautiful girl, especially as I did not have a pronounced Jewish appearance, with long light brown braids; by and large, they accepted me for employment. I got a ladle of soup every day. It was nearly a liter, with rotten meat, and a small slice of bread. I ate some of it and the rest I carried to the ghetto for my brother. Around the time that mum died typhus raged throughout the ghetto. Georgy fell sick. But our savior Abram Aronovich procured Sulfidine for a lot of money. This at least saved the child.