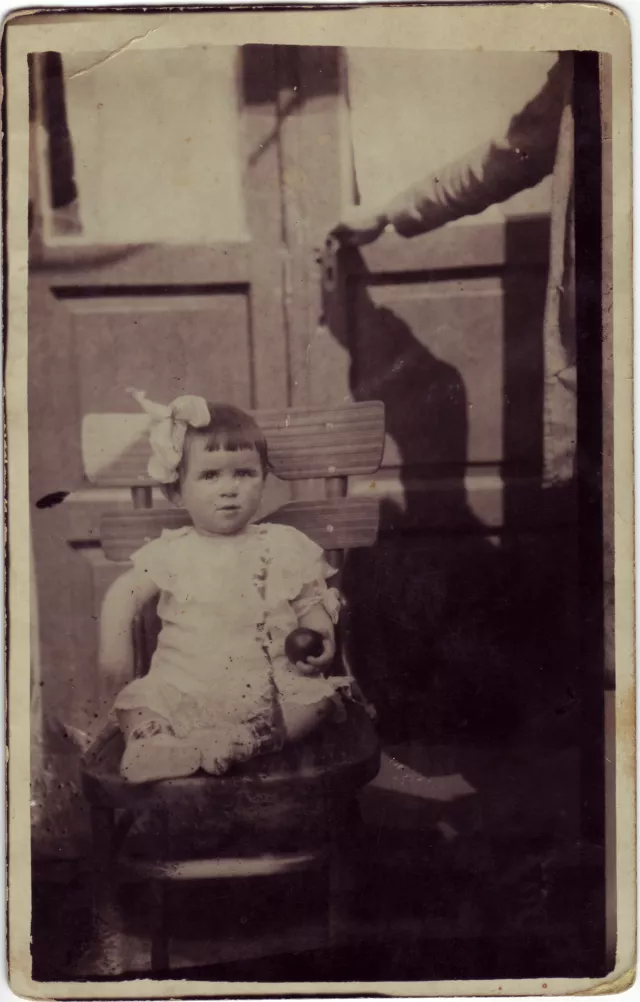

This is me, Rifca Segal, holding a ball in my hand. I think I hadn’t even turned one year old. They just put me on a chair in front of the store my father, Aizic Calmanovici, owned in Sulita and they took this picture.

My parents got married in 1927, and I, Rifca Segal, was born in 1928 in Sulita. Officially, my name is Rifca, they named me after a great-grandmother, the mother of my grandmother from my mother’s side. But people call me Rica, as Sulita’s county chief – his name was Hotupasu – had a daughter whose name was Rica. And my parents were very good friends with the county chief.

Until I was 13, my childhood was a happy one. After that… it was awful. We had been rich until 1941, when the legionnaire regime came to power and they kicked us out of our home and we left with the clothes on our back. And we began to experience dire poverty. Hadn’t the legionnaires come to power, we would have had such a good life in Sulita. They destroyed us back then.

We kept our window shutters closed, we were afraid of the legionnaires. And one day that man who used to carry sacks at the mill came, he had become a great legionnaire, and was one of their front-ranking members, and he pounded on the window shutters: “All Jews must prepare for they have to leave.” At first, they didn’t tell us where we had to go. At first, men were supposed to go somewhere, and women and children somewhere else. But there was this woman, Filica, she worked as a telephone operator at the post office in Sulita, a woman of extraordinary nobility, whom my parents had befriended. My parents were very good friends with the mayor, the county chief, the notary, the scool principals… And there was nothing they could do, poor souls. But this woman, Filica, came and told us: “You know, if they find out, they will shoot me on the spot.” And I remember, she took my father in the back room – we didn’t know what was happening, we were also scared –, and she told him that a telephone call came through from Botosani, that they didn’t have train cars to send the men and women separately, and so we all had to leave to Botosani together for the time being. Well, we were happy to hear that.

And in June 1941, when we came to Botosani, a drizzle was falling – it was very fine, with no lightning’s or thunders –, and we sluggishly came to Botosani in a cart pulled by oxen – a distance of 32 km [35 km]. We were supposed to look for a peasant to rent a cart from him. We brought along as many things as we could carry. I couldn’t tell you exactly what… But I do remember that we certainly brought along a quilt, a pillow, the clothes that we were wearing, for we couldn’t take more, there were 6 of us. I had another sister and a brother, and my father’s grandmother lived with us. And so my parents plus my grandmother were 3 persons, and with us, 3 children, we were 6, all in all. Well, how many things could we take with us? For the entire merchandise, things, furniture, everything was left behind. And then the legionnaires burned it. They burned everything, houses, things. And you imagine, a fine rain was falling, and we used whatever we could take along in order to cover ourselves. We traveled in a group of carts moving together and accompanied by gendarmes. And they left us in the cattle market, where there was a cattle sale the following day. And the following day we were free to go wherever we wanted, for it was a cattle market, and people were coming there to sell cattle.

After they evacuated us, we were very destitute. We became poor people. I couldn’t say how we managed to get by. At a certain point we lived in a house located near the street, and they allowed us to open a small small ware shop. But I don’t know if it was enough for them to make ends meet. I remember that once, as a child, I told them I wanted to eat two eggs, and they told me they couldn’t give me more than one egg, for they had to give some to the other children as well. Do you know how sad it was? I liked eggs, I still do to this day, mainly fried. And I said: “I want two eggs.” And I started to cry. And mother, who was more severe, may God forgive her, would tell me: “I have 3 children, I must give an egg to each of them.” I wanted to show you how we lived. It was horrible. We almost considered begging in the street. But we were also helped by this sister of my mother’s, Branica. It was very difficult. I remember, they paid the rent for us. My uncle had sheep. I believe he had them registered under the name of a Romanian peasant.