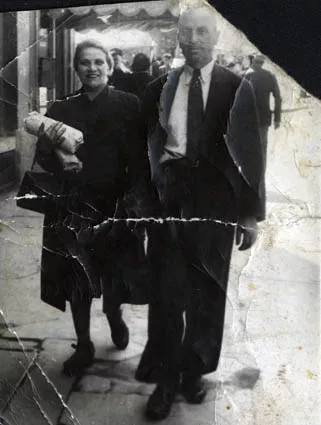

In this photo are my mother Liza and my father Yuda (Zhoudi) in a street in Plovdiv. They are going to the shops. There is no stamp of a photo shop on the back of the photo, nor any other inscription. The year was 1943.

My father Yuda Samuil Behar was born in Plovdiv in 1896 and died in 1959 there. There were six children in the family which means that dad had five more siblings – Bouka, Nisim, Sofi, Rebeka, Stela. He finished the fourth grade at the Jewish school. And irrespectively of the fact that he had only primary education, he was quite a specialist on Bulgarian grammar. He knew it better than the majority of people because he worked as a typesetter for years and years on end. When he turned twelve he started working as an apprentice at a printer’s. At that time the local, Plovdiv, newspapers were printed there as well as the Jewish newspaper at that time ‘Shofar’ [a Jewish newspaper, issued in Plovdiv and Sofia from 1919 till 1944.] In his spare time he was reading books with a pencil in hand and we could often hear him say: ‘Oh, bullshit! Here a dash must be put, here – a comma, and here – a semi-colon.’ I remember a very interesting occasion. I had a little book with his corrections. After his death I decided to give it to the greatest specialist on the Bulgarian language at the time – the teacher Vera Gulubova. At that time I was a student at the Rabfak[Worker’s Faculty] and she was my teacher. ‘Comrade Gulubova, I want you to tell me if this correction is accurate.’ And about a month and a half later she brought the book back and told me: ‘Behar, who has done that correction – because that is a person who is perfectly familiar with the grammar of Bulgarian.’ I told her that it was done by my father – a person who had finished the fourth grade but who worked as a typesetter for 52 or 53 years. He didn’t know what the rules were for the usage of commas and dashes but had an intuitive feeling as to where to put them. My father had always been a well-informed man, he worked at the printer’s after all. Apart from being a typesetter, he was also a stamp-cutter – he was making stamps. On top of that he was very skilful and could engrave with slate pencils. Yes, he was skilful indeed – he was making his living with his two hands but the money he was earning was only sufficient for a meal every day and for bread.