Elvira Lidgi after her husband Buko Lidgi’s death

In this photo is my mother Elvira after dad's death during the Holocaust in 1942. You can see the badge [yellow star]. In her eyes are reflected all difficulties she had to go through in those hard times.

[After my dad’s death] mum remained without any resources because everything we had was mainly from the companies that dad had assisted and they paid him, or, as it turned out later, some of them hadn't paid him anything.

And dad was buried at the lowest possible price, according to mum's words, but I didn't know what exactly that meant. Mum started to look for a job. Robert Kohen's family, who was an acquaintance of uncle Mois Beniesh and owned a haberdashery in 'Pirotska' street, helped her initially. He gave her 2, 000 leva, somebody anonymously bought us coal and wood for the winter, then she got some other aid again, but the situation was terrible because mum was still without work. After dad died a neighbor, Marko Rahamimov, my friend Eti Rahamimova's father, taught her accountancy. She had helped my father while he was still alive but she didn't know accountancy. The knowledge she acquired was of help later.

Soon after dad died, while she was still without work and the situation seemed desperate, she thought of leaving a letter to my uncle Isak. She had a plan - to get up earlier and to jump under the tram because she couldn't see a way out of her awful situation.

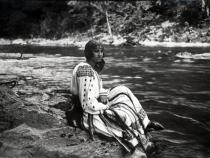

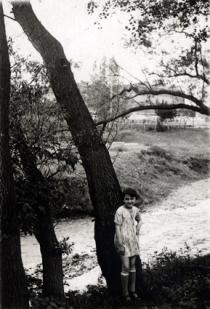

I will tell one of her dreams after dad's death, which she told me on waking up and from which, she believed, she got information about the future course of our life. She dreamt that my dad and granny Sarah came near her bed and told her, 'Come with us.' She was in her night gown and while walking on a way she said, 'I can't…'. There were torns. She then saw a bloody trace in front of her, but he told her to continue and they reached the bank of a river. He said, 'We will go to the other side and will throw something for you.' And then she saw a big fish in the air but the fish fell into the water. Granny Sarah shouted from the other side 'Don't worry, we will throw something again.' And they threw a small fish. She woke up. And she woke up later than the possible time at which she could wake to throw herself under the tram. And she told me the dream then. And I smiled and said, 'Well, Mama…', can you imagine to say that, at the age of twelve, 'Mama, this is just wishful thinking.' At that moment, and this is really strange, it is difficult to believe in these things, so at that very moment a neighbor, the wife of Rahamimov - the person who taught her accountancy, came to look for her. She said, 'Elvira, I read that they are looking for electricity collectors.' And mum, using the information from the advertisement, took an exam for electricity collectors in Sofia. The exam was very difficult, but she passed all the exams and they hired her in the electricity company. The situation was complicated, but as the company was international, they could hire her even though she was a Jew. They had that right and then again some strange force helped her. She started going round Sofia and taking down the indications from the electric meters.

One day, an assistant of hers from her previous job saw her and asked her, 'Mrs Lidgi, what are you doing here?', 'Well, I am here at work.'. This work involved going round the streets, to measure and calculate the indications from the electric meters. And this woman went immediately to Mr Kastermans, a director of the electricity company, and said, 'Mr Kastermans, I want to take Mrs Elvira Lidgi in my department, as my employee.' and she actually went there, to a better position in the accountancy department of the electricity company.

And after that, just think about that dream! - one day she met the very director of the insurance company 'Asicurazione Generale', where my mother had worked until I turned four. He asked, 'Mrs Lidgi, why are you in mourning?', because mum was wearing black from head to toes after my father's death. 'Why? What's happened?' 'Well, I remained a widow.' 'Do you have a job?' She told him where she worked, after which he offered her a job - much better and well paid. In this way she changed her job for the third time after my father's dad. So she started work there, it must have been in 1941 and stayed there until our internment.