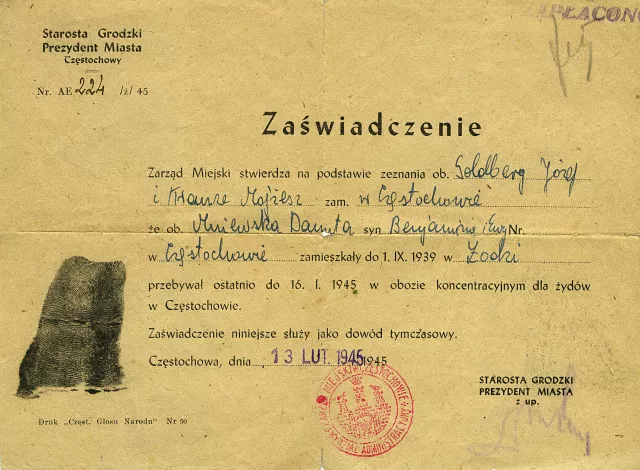

Danuta Mniewska's temporary ID in 1945

This is a certificate which I got in February 1945 in Czestochowa. It confirmed that I had been in a concentration camp [labor camp in fact] in Czestochowa, the Hasag, until 16th January 1945. This document served me as a temporary ID.

Uncle Roman Markowicz was a very wise man. Before the war, he owned a textile factory in Bielsko - very rich people. One day, at the camp, he told me that I had to change my job and join the column of those going to work on the Aryan side, so that I was in touch with the Poles. The point was to secure false papers for us. There were groups of people at the camp that worked at the Hasag, the Rakow steel plant, the Czestochowianka or the Peltzery [pre-war textile factories, working for the German military industry during the war]. And so I joined one such group, of some 15 people, who worked at a large square at the outskirts of Czestochowa where the rubbish from all over the city was being brought.

Our job was to separate rags, glass, paper from that rubbish - it's called recycling these days. The company running that was called Ravo. We weren't guarded by Germans but by Ukrainians, Latvians, and the 'saulis'. The work was very tough, and it was already severe winter, but the square was where all the trade took place. The Aryans came to us - some produced false documents, others brought food, still others bought dollars from the Jews. And indeed, I secured those false IDs - I still had one of those gold coins my father had given me.

Uncle's various employees also came there - it was the only place because they weren't allowed to enter the camp. Uncle put great trust in his manager, Mr. Pastuszko - he was his 'banker.' And rightly, because he was a very decent man. Another one, Domzal, a young Home Army soldier, took money from the 'banker' guy and brought to us. Uncle started thinking about setting up some hideout on the Aryan side; that eventually we'd have to escape from that camp. He asked a worker from his factory, Mrs. Siminska, to find someone who for money would prepare a hideout - a shelter.

The one who agreed to do it was called Klimczak. His wife was opposed to it, was afraid - they had a five-year-old daughter. A little house was bought in his name on the outskirts of the city, a neighborhood called Piaski, beyond the Jewish cemetery. He was to organize everything there, build a room for eight people. The house was now his property, and after the war he was also to receive a two-story house in Czestochowa and two building lots.

.At the end of November the shelter wasn't yet ready, we were still in the camp. And one night I return from work to the so-called home and there everyone's crying, wailing. There was a raid; they were looking for people hiding away. Uncle and Aunt hid somehow, but Bronka, their daughter-in-law, and her mother were gone. Someone told us that two dead women lay by the fence. It was a frosty night, the moon shone, you could see everything. Bronka's husband and his brother crawled up to the wire. And indeed, they lay there. They buried them. They return home and it turns out the IDs are gone. No one knows what happened to them, whether the Germans took them or the Jewish police, the Polish police? Or perhaps Bronka and her mother took them before they ran away? So Bolek and Lucek return to the fence, dig them up, but find nothing.

Within a couple of hours we had to organize an escape from the camp. That wasn't a problem - you simply joined a column going outside. There were no Germans there, only Polish and Jewish police. Aunt, I and Uncle and Aunt's niece, Mirka, went to Klimczak's apartment. There was only one room there, the door was always open, no one bolted doors in those working-class apartments - if the neighbor wanted to enter, she simply entered. And we were hidden in a 'done' bed. During the day we had to lie flat under the eiderdown, you weren't allowed to move. During the night we went out. And the men and my sister went to the house that had been bought, pretending to be the foreman's helpers. That may have lasted some two weeks.

We lived there for a full two years - from December 1942 to January 1945. Towards the end of 1944, when the Germans were already fleeing, they seized part of the house and put four pilots there - they lived behind the wall. We behaved as if we didn't exist - silence, lock and bar. When they went out, Klimczak would knock on our door and tell us we could go out. Someone sat in front of the window at all times, so there was always time to go into the hole. That lasted for a month. Such miracles happened too.