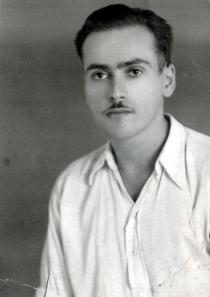

Asaf Auerbach

Asaf Auerbach

Prague

Czech Republic

Interviewer: Lenka Koprivová

Date of interview: October 2005 - February 2006

Always, when I came to see Mr. Auerbach, he was in an excellent mood, constantly smiling; I don't remember ever seeing him frown. On the contrary, he sings, whistles to himself...

After the death of his wife, he is living with Robin, his dog, in one of Prague housing developments. He says that his life isn't very interesting - but... His parents were Zionists and Mr.

Auerbach was born in a Palestinian kibbutz. Nevertheless, the family returned to Czechoslovakia, lived here through the difficult 1930s, and at the end of the decade was split up.

Asaf Auerbach and his older brother Ruben had the luck to have been included among the so-called Winton children 1, a group of children that the Englishman Nicholas Winton managed to save.

They lived in England during the war, and upon their return home to Czechoslovakia, were confronted with the horrible reality of the fate of European Jews.

Despite all expectations that they had lived on for the entire time of the war, many of them did not manage to return home and have a joyful reunion with their parents - the Auerbach parents also died in Auschwitz.

Mr. Auerbach says that his life isn't interesting - that's not completely true.

- Family background

You want me to talk about the family in which I lived, about my ancestors, what environment surrounded me, a member of an ethnic minority, living only occasionally in harmonious symbiosis with my surroundings. The last time I saw my parents was in the summer of 1939, when my brother and I, as Winton's 'children,' immigrated to England.

I was eleven, at that age I wasn't too interested in these things, I took them as a matter of course, I don't think that it interested any child of my age that didn't for example come into immediate contact with aggressive anti-Semitism.

I knew it only second-hand; to a certain degree I knew about what was happening in Germany from my parents. So I didn't have too many reasons to ask questions, it was more a question of me receiving information, than seeking it out.

I didn't get around to familiarizing myself with my earlier past until very late. By chance. About six years ago I read, most likely in Rosh Chodesh 2, which is a monthly newsletter of the Jewish community, a remark regarding the fact that an almanac had been published for I think the 900th anniversary of the founding of Becov nad Teplou, and that in that almanac there was also an article about the history of the local Jewish community.

That was already a strong impetus, as my father had been born in Becov. And so I went to the Jewish Museum to see the article's author, and asked him for a copy. In it I found out that the presence of Jews in Becov has been historically verified since the year 1310, that the number of Jews there gradually increased, and their number peaked in the year 1880, when there were 100 Jews living there, about 4.5 percent of the local population.

I wanted to delve into my father's family tree, so I borrowed the birth registers of the Becov Jewish community from the State Archive in Hradcany [a Prague quarter], but I didn't get very far. It wasn't until during the rule of Josef II 3 that Jews were forced to adopt family names, and the first preserved records of births and marriages in Becov date from that time.

The death register has been preserved only from the year 1840. And so I don't know when my ancestors moved to Becov, and from where. And it wasn't easy to decode the registers. They're written in German, what else, of course. But one can't at all talk about black-letter [Gothic] script or good penmanship. Nevertheless, I easily found the record of the birth of my father Rudolf, on 23rd March 1899, to Simon Auerbach and Luisa, born Fischerova.

Their marriage, however, isn't recorded in the register; I don't know where it took place.

Grandpa Simon is recorded in the birth register as Samuel Auerbach, born on 8th June 1849, as the illegitimate son of Abraham Auerbach and a certain Löblova, whose first name I was unable to decipher. He had already had one son with her, born on 16th July 1847. He subsequently took my great- grandmother as a wife, and that in July of 1849. Her age isn't listed in the marriage register, though that was the custom.

She wasn't my great- grandfather's first wife, though. That was Babette Kleinova, whom he married on 28th October 1840. At that time he was 30 years and 3 months old, the bride 29 years and 11 months.

It was probably a childless marriage, I didn't find any offspring in the birth register, neither did I find my great-grandfather's first wife in the death register, so it's possible that he repudiated her because she hadn't born him any children, and thus he could marry the mother of his illegitimate sons.

According to the register, great-grandfather Abraham died of marasmus in 1896 at the age of 86. In the death register I found a record of the death of Fanny Auerbachova in 1902 at the age of 86. Thus she was born in 1816, and so could have been my great-grandmother, born Löblova.

From information about the age of Great-grandpa Abraham at the time of his first marriage, I know that he was born in July of 1810. I, however, didn't find a record of his birth, so he probably moved to Becov, and thus prevented me from searching for my great-great-grandfather.

And it's not because of the fact that my searching was marred by the fact that Jews didn't have family names, during the time of his birth they already had to have them.

And so I don't know where they came from. I've got this unconfirmed hypothesis. North of Becov, several tens of kilometers on the other side of our border with Germany, lies the town of Auerbach. A co-worker of mine sent me a postcard from there 15 years ago. It's a picturesque little town called Kurort Auerbach, we used to call these places a climatic health spa. Some time ago I was playing around with the thought of going there, renting a hotel room, and when I tell them that my name is Auerbach, they'll gape at me with open mouths. But to go there just for that?

The name Auerbach isn't rare, that's only the case now, in the Czech Republic, earlier it was quite common and in other places it's probably common even now. Not long ago, one friend of mine was even telling me that she'd read somewhere that it's the oldest documented Jewish surname in the Czech Republic.

I've never heard that before, but I'm not ruling it out. At the Old Jewish Cemetery in Prague, on the wall that runs along the sidewalk on which you walk through the cemetery, there are tin plaques with names on them, across from the graves of prominent people. The very first one says, here is buried a certain Auerbach, who was a contemporary of Rabbi Löw 4 and Emperor Rudolf II. [Rudolf II. (1552-1612): from the Habsburg line; 1576-1611 Roman Emperor and Czech King] So that was at a time when Jews didn't yet usually use surnames. I don't know how many times I've said to myself that I should drop by the Jewish Museum and ask someone what made him so important, but I've never gotten around to it.

Back to Grandpa. According to the marriage register, on 1st March 1882 Samuel Auerbach, single, married Anna Luxbaumova, aged 31 years and 1 month, who is listed in the register as the mother of three children, begotten with - now already - Simon Auerbach. The oldest, Jenny, was born in 1883, I don't know when she died, I never knew her, I didn't even know she existed. It wasn't until after the war that I found out that she was mentally ill and died in a psychiatric institution. Whether it was before the war or not until during its course, that I don't know, I didn't want to ask. But I knew my father's half-brother Leopold, who was born in 1885, he was the only one in the family that was wealthy, he had a shoe store and a large residential building in Karlovy Vary. He used to occasionally come to Prague and visit us, but it wasn't often. He was single and in 1940 he managed to escape to Palestine. He didn't do very well there, he died in the mid-1950s. He was an unusually self-sacrificing person, he supported my grandmother, his stepmother, after Grandpa's death he bought her a house in Terezin, where she had a small store, my father used to commute from Terezin to Litomerice to attend business academy. And so he also likely financed the studies of his stepbrother and stepsister, who graduated from conservatory.

I didn't find Simon Auerbach's second marriage in the register; he probably married Luisa, my grandmother, in a different town. I don't know where my grandmother comes from. My cousin told me once, when I asked whether Grandma spoke Czech or German, as I didn't even remember that. She came from the interior of the country and so knew Czech well. Grandpa had two children with Grandma. The first to be born was Aunt Ida, in 1897, and after her on 23rd March 1899 Rudolf, my father.

Grandpa died in Becov on 13th March 1914 at the age of 64 years and 9 months. It's rumored that he was an alcoholic. Neither my father nor aunt ever talked about him. That doesn't surprise me. As I've already said, Grandma then moved to Terezin with the children. But I remember her from a later time, when she was living in Nusle [a Prague neighborhood] with her daughter, Aunt Ida. Grandma wasn't very talkative, which is why I couldn't remember whether she spoke Czech or German. All I remember of her is how she's sitting in the kitchen on a chair, smiling slightly, her hands in her lap. My cousin was telling me how she once had a terrible argument with her daughter, packed her things and went to live with her son, so with us. But the move from the usually calm environment at my aunt's place, where the most noise was caused by a grand piano on which my aunt gave children piano lessons, to an apartment where two brothers were constantly arguing and fighting, that was going from the frying pan and into the fire, and apparently a few days later she packed up her things and repentantly returned to her daughter's place. But I can't guarantee that it's all exactly true.

In 1942 my grandmother was deported to Terezin 5 and there she died a so- called natural death due to unnatural conditions. Otherwise she would have lived to be older. I don't remember the date of her death, I'd have to go to the Pinkas Synagogue and find it there on the wall.

So now on to Aunt Ida and her family. She finished conservatory, piano. She married Otto Drucker, a civil engineer. In January 1927 she had a daughter, Dita, and in February of 1929 her husband died of an inner ear infection. He ignored it, it was right at the time of the legendary deep freezes that were plaguing Central Europe back then, and so my aunt became a widow at the age of 32. She didn't remarry, so those three women of three generations, Grandma, her daughter and granddaughter lived together. I didn't have it far from our place in Vrsovice [a Prague neighborhood] to theirs, and I visited them about once every 14 days, I don't know exactly anymore, mostly I used to go alone. On foot.

My aunt and cousin survived the war in Terezin; my aunt once told me that my father twice managed to reclaim her from the transport to Auschwitz, for which she had already been scheduled. He had some influential friends. So who knows, maybe it was good that she never remarried. For sure it would have been harder to save them both from the transport, and so in the end maybe both of them would have gone to Auschwitz. How Mengele would have decided regarding their fate, that's something I have no doubts over.

She didn't have it easy after the war. A small pension after her husband - how much could have it been after about five years' employment - my uncle could no longer support her, there weren't too many piano lessons after the war, her prewar 'clientele' had most likely been predominantly Jewish. The relatively large apartment in Nusle, where they lived up until the transport to Terezin, was never returned to them. Instead, they gave her and Dita a sixth-floor attic bachelor apartment in Pankrac, which had a slanted ceiling and about 16 square meters [about 170 sq. ft.], without an elevator, so they lugged coal from the cellar up to the sixth floor on the stairs. When Dita immigrated to Australia in 1949, I visited my aunt quite often, and would always carry up a stockpile of coal for her.

My aunt left to be with her daughter in the spring of 1951, at first she lived alone, she worked in a café where she made coffee and tea, later, when my cousin and her husband had a house, she moved in with them. After some time she started getting some sort of pension from Germany, within the scope of the so-called 'Wiedergutmachung' [German for 'compensation'], which was enough for her. We wrote each other often, up until she died in 1986. Once she was here on a visit, accompanied by her daughter, that was in May of 1978, right when I was celebrating my 50th birthday. Now Dita comes all that way to visit relatively frequently, once a year, two at most - I actually see her more often than my cousin on my mother's side, who lives in Most. Not that there are any problems between me and my cousin from Most, it just doesn't work out time-wise.

Dita was telling me that in Terezin one Gypsy woman read her cards and predicted that she'd meet her future husband on a ship. She kept an eye out for her future husband on the merchant ship that took her from Marseille to Sydney for more than two months, because they were loading or unloading cargo in every port along the way, but he wasn't there. And then she met him on a ferry in Sydney. Which is also a ship. So the Gypsy woman didn't lie. He's a Hungarian Jew, before the war he immigrated to England and after the war he moved to Australia, they've got two sons, and four grandchildren. Her husband is still working, for a brokerage. And he's already over 80. Apparently sitting at home and doing nothing would do him in. At least that's what Dita claims.

I don't know any more about my father's family. Now on to my mother's family. She came from a different environment. My father's family, those were very poor German Jews, my mother, on the other hand, came from a middle class, Czech Jewish environment. My grandfather, Jindrich Fantl, born in 1867, was from the village of Chlebnik. My grandmother, born in 1873, had I think always lived in Prague. I knew her mother, thus my great- grandmother. She was named Roza Epsteinova, was born in 1848, so the year when my one generation younger Grandpa Auerbach was born, and died in the year 1936, by then I was eight years old, so I remember her. She'd apparently had a pub, but by the time I knew her she was already living with her daughter, for many years she took care of her household, because Grandma spent a lot of time in the store. Her grandchildren loved her. I've got the feeling that they were closer to her than to their mother, probably because she had more time for them.

When my mother and I would go to visit her parents in Smichov [a Prague neighborhood], where by U Andela, in a building that's been since torn down, Grandpa had a men's wear store, and that was regularly once a week, we'd always first go see my great-grandmother. And when we didn't find her at home, we'd find her in a small park by the Vltava River. She always had a piece of hard candy for me in her pocket. Or several stuck together. Only then would we go to the store to see my grandma and grandpa. My grandfather, grandmother and great-grandmother, and before that also with their children, lived on Vltavska Street, a few minutes' walk from the Andel neighborhood. It was a typical spacious bourgeois apartment in a building from the turn of the century.

In the shop my grandmother reigned behind the till, and Grandpa 'officiated' in the back in the 'comptoir,' which was a narrow, dark hallway surrounded by walls and a wall of shelves in the back, at its end was a writing desk with a desk lamp, telephone, typewriter and other such things, and here on the other hand reigned my grandfather. Once in a while he'd allow me to use the typewriter, which I considered to be a major show of favor on my grandfather's part. And my aunt Oly served customers behind the counter, along with an assistant. Later, when Grandpa handed the store over to Aunt Oly, they used to send me for Grandpa to a nearby café, where he went every afternoon, except for Sabbath of course, for a game of cards. There I always found him with an obligatory cigarillo and an unfinished, cold cup of black coffee. He always finished the game, drank the rest of his coffee, and without complaining that he was having a good run of luck, collected his change from the table and left with me for the store.

They had four children. The oldest, Marketa, my mother, was born in 1900, a year later Uncle Rudolf, with a greater intervening period in 1908 Aunt Olga, and in 1915, Aunt Mirjam. Uncle Rudolf was a civil engineer, I used to see him infrequently, he was at the construction site of a tobacco factory in Southern Slovakia, as a construction supervisor for the Czechoslovak Tobacco Directorate, which was a state-owned monopoly for the processing and sale of tobacco and tobacco products. He was single, and had a steady girlfriend, a Christian girl, who was pressing him to marry her, but he didn't want to endanger her, and didn't want to get married until after the war. If he would have married her, his life wouldn't have ended somewhere in Poland, but how could he have suspected that?

On the other hand, Aunt Olga survived precisely because in 1937 she married a Christian, who was also a civil engineer, a German from Tesin, who graduated in German technology in Prague, Oskar Dworzak. So his ancestors probably hadn't been again all that purebred Germans. Of course, they pressured him to get divorced, but he didn't give in, perhaps thus he also saved his own life, because for that reason he didn't get drafted to the army. He could also have frozen to death by Stalingrad, or if he was luckier been displaced or expelled 6, pick the word that you prefer. To be sure, my grandfather, an Orthodox Jew, didn't like a marriage with a 'non-Jew,' neither did he participate in the wedding, neither he nor my grandmother are in the wedding photographs.

Worse off was Aunt Mirjam. While she had married a Jew, she had done it a year before her sister, and that was also hard for my grandfather to come to terms with, as she was supposed to have waited until her older sister got married. Jews don't do that sort of thing. She experienced Terezin, then a half year with her husband in the so-called family camp in Auschwitz, they both made it through the selection, but were separated, and Uncle Oskar died of exhaustion during a death march 7, several tens of kilometers from Terezin, where they were leading them on foot. After that my aunt was in Hamburg, where they were mainly clearing debris after the bombing, she lived to see the end of the war in Bergen-Belsen, which during the last days of the war was perhaps the most horrible place in the world.

After the war Aunt Mirjam married Frantisek Klemens, who had returned to Prague after immigrating to England, where he had served as a bomber navigator, he then finished his medicine studies here. The StB 8 harassed him, they had something on him, and promised him immunity if he made a pact with the devil as a collaborator, which he refused, and so in 1951 they decided to cross the border illegally. At that time they already had two children and a third on the way. Dr. Klemens was afraid to give the younger son, back then two or three years old, whom he was carrying on his back, a sufficiently large dose of sedative, and he woke up at the worst moment, began crying, and so the border guards caught them.

My uncle was in jail for a relatively long time, they added some time for an unsuccessful attempt to escape from jail, my aunt served, I think, a half year, and that was even split into two stages, they were so 'considerate' that they interrupted her sentence so that she could give birth outside of the jail. Most likely they didn't have an obstetrician or midwife there, that's why. And so during this time Aunt Oly [Olga] had five children to take care of. Unenviable.

After he finished his sentence, my uncle was barred from practicing medicine, he worked in a factory, and they decided to emigrate legally, which took a long number of years before they gave them permission. They immigrated to Israel, my uncle has since died, and my 90-year-old aunt now lives with her daughter. My cousin Ivan, Aunt Olga's son, writes in detail about these hard times in his book named 'Report.' I didn't have any closer contact with them during the 1950s and 1960s, they moved not long after my uncle returned from jail to Pisek.

Actually, I've forgotten to talk about the further fates of Grandpa and Grandma Fantl. Grandpa was lucky - you can't call it anything else - he died in his bed of pneumonia in May of 1940. I can't imagine how he would have borne those horrors. He wouldn't even have survived Terezin. When I once told Aunt Mirjam this opinion of mine, she agreed with me. My grandmother was made of different stuff, she was a fighter with immense energy, who wasn't one to give up just like that. At the age of 72, in Terezin, she fell ill with typhoid fever. I don't understand how in those conditions she managed to survive typhus and live to see the end of the war there. She wouldn't have survived Auschwitz.

My grandmother died in 1954. The close of her life wasn't easy either. The last two years she lived in a Jewish old folk's home, she certainly wasn't happy there, that was clear to me when I used to come visit her. Back then old age homes looked a little different from today's retirement homes and because she didn't have anything to occupy her, her head was beset with probably very sad memories of dead children. I liked her very much, after the war she was the closest to me of all my relatives.

So now I should finally return to my parents, my and my brother's fates? I'm loath to; it still hurts, even after so many years. My parents' youth was marked by membership in a Zionist movement 9 that was 'in' in those days, that's how they say it today, right? There they most likely met, and were preparing for the return to the Promised Land. They were preparing for kibbutz work on some farm, and were learning Ivrit, or modern Hebrew. In 1922 they emigrated to what was at that time the British Protectorate of Palestine. They became members of the Bet Alfa kibbutz, they were among the founding members, they arrived in a wasteland that had been purchased from Arab sheiks, set up tents and gradually fixed it all up.

On a photograph from the year 1930, it already looked very good there. It's a view from a hill, on the hillside is a large orchard with already full- grown trees, most likely orange trees, at the bottom of the hill is already a number of buildings, especially farm buildings. While digging their foundations, they came upon a preserved mosaic floor of a synagogue from the 6th century, so it's been made into a museum. It's quite well known, I've already seen photos of that mosaic in several publications.

A kibbutz is an agricultural cooperative, which functions on the principle of each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs. However very modest needs, depending on the kibbutz's means. They ate together, when their pants were torn they got new ones, etc. In other words, the basic idea of communism. How they addressed the problem of non-smoker versus smoker of 10 cigarettes a day versus a smoker of 30 cigarettes a day, I don't know. Maybe they got some sort of allowance. There are still kibbutzim in Israel today, there are less of them now, and they don't live as Spartan a life in them now as back then. They joined the kibbutz voluntarily; they could join anytime and leave anytime. After the war, immigrants often began their lives there, before they had a chance to look around and decide for a different, more independent life. So in the kibbutz they had and likely still have a somewhat different relationship than our co-op members had to their co-op, which probably also showed in their work ethic. President Masaryk 10 went there to visit them, some photographs have survived of him talking to the kibbutz members in the mess hall, but they're dark and out of focus.

Well, and we were born there. Not in Bet Alfa, but in Ain Harod, which is a nearby town with a hospital. First my brother Ruben on New Year's Eve in 1924, and then I in May of 1928. The confirmation of my parents' wedding by the head rabbinate in Jerusalem still exists. It wasn't until 1926, probably a mass wedding of all couples that had up to then been living together, most likely the rabbis were scandalized, and so the kibbutz members did it to please them. They themselves probably didn't care. Thus when he was born, my brother was illegitimate, but nothing of the sort is written on his birth certificate. While on my birth certificate I erroneously have it written that my father is Polish. My parents probably didn't care one way or another, after all, they were just Jews.

It wasn't until right before our return to Czechoslovakia at the end of 1930, that my father, like it or not, had to go to the registrar's office in Ain Harod and there sign an affidavit that he's not Polish, but a Czechoslovak. On the basis of this, the relevant registry clerk wrote on the back of my birth certificate that on the basis of the attached affidavit, Nationality Polish is changed to Nationality Czechoslovak. In this simple fashion I changed my citizenship. Here it would probably have been more complicated. Especially after the war. I have one memory connected with the trip from Palestine. It's not guaranteed, I could also have suggested it to myself after the fact. I'm standing on the deck of a ship, and in front of me is nothing but the sea. It could be a real memory, the difference between parched Palestine and the Mediterranean Sea could have made a deep impression.

Why did we return? That I don't know, I didn't ask; why should have I been interested in that back then? I didn't even know what Zionism was. Back then a number of families were returning, probably mainly due to health reasons, the climate there is quite different than what they were used to, and also physically demanding work, I heard that malaria was rampant there, so probably mainly due to that. We kept in touch with several of these families here as well. Of course, after the war there were many times that I said to myself that if back then my parents would have endured it there, everything would have turned out differently. Probably during the war, maybe for the last time on the ramp in Auschwitz, they also said it to themselves. How many times in life do we make a key decision, which we then regret when we subsequently realize its effects on the rest of our lives? What happened couldn't have been predicted in 1930 even by astrologists. At that time Hitler was still a ridiculous, insignificant zero. Three years later, they would have most certainly already decided differently.

And so we found ourselves here during the time of the Great Depression 11. The beginnings were probably not easy, we came with nothing but our bare hands, how my father found work in that situation, I don't know. We boys didn't speak Czech, I had enough time to learn, I was two and a half, but my brother had to hurry up, he had three quarters of a year to manage it before the start of school. But in England we had much less time for it. In the beginning, up until I was six, we lived in an apartment building in Zizkov [a Prague quarter]. I have almost no memories, just that for a year I attended nursery school at Na Prazacce, back then it was a brand-new school, that's probably why I remember it. And then I also remember that there was a shoemaker in our building, more like a cobbler, that I used to go visit him in his dark little shop, curious as to how he did it, and he'd tell me things. I don't remember what our apartment looked like. Actually not even the next one, where we lived for two years. That was in Podbaba, a little ways up the hill from the last streetcar stop. There I began attending school. I remember school. It was in several temporary single- story wooden buildings, in each one two classes across from each other. There were more of these around Prague, my wife then studied in such a one at the beginning of the 1950s in Branik [a Prague quarter].

When at the end of the summer holidays in 1936 we came back from pioneer camp 12, our parents were waiting for us at the train station, but instead of Podbaba we drove to Vrsovice. To our third, and last apartment. They didn't tell us about the move ahead of time, it was a surprise. It was a new building, the apartment was more spacious, there was a large living room, which was the children's room and dining room, our parents had a room that was a little smaller, and along the entire width of both rooms there was a balcony. It was about the same size as the one I have now. The kitchen had only indirect light, between our room and the kitchen there was a wall with glass bricks from a meter above the floor to the ceiling. It was already a modern apartment, with central heating, hot water, an elevator in the building, in the basement there was a laundry room with a washing machine and a heated drying room. There I finished attending what was back then called elementary or grade school, it was Grade 1 to 5. At the end of the school year in 1939 I applied for council school, but I didn't actually go there. At the end of July my brother and I left for England.

My memories of childhood are basically tied only to Vrsovice. Back then it was still full of empty lots, a little ways away from us were the barracks of the 28th Infantry Regiment and its military training grounds, we children were also allowed on them, a few hundred meters further Eden, with merry-go-rounds and a summer athletic grounds, which in the winter changed into a skating rink. We had everything. Back then I read a lot, that was my favorite pastime, to lie on my stomach and read. At home we didn't have a lot of books, I remember only Svejk 13, which I faithfully read in its entirety, from children's books I remember Capek's 14 fairy-tales and Dasenka and also the book 'Bambi' by some Northern author, it was about the life of a fawn. [Editor's note: 'Bambi' was written by Felix Salten (1869- 1945): real name Siegmund Salzmann, Austrian-Jewish author and theater critic, president of the Austrian writer's association P.E.N-Club from 1927- 1933. Salten lived in Vienna most of his life, but fled to Zurich during WWII. 'Bambi' was first published in 1926, Walt Disney acquired the film rights in the 1930s and the cartoon film first came out in 1942.] I liked that one a lot. It was bound with green cloth, with gold lettering. Probably someone gave it to me for my birthday. I took it with me to England, where it probably remained. I used to go to the children's library regularly, it was on Korunni Trida [Avenue] in the Vinohrady quarter, beside the water tower, on foot it wasn't even a half hour. That children's library is still there.

How do I know? I take my dog to a vet in Vrsovice. I found him once long ago in the phone book, when we got this Welsh terrier, he's named Dr. Bondy, so it was obvious that he's co-religionist, so why wouldn't I support him, and what's more Vrsovice, which I still have nostalgic memories of. And so I go there at least twice a year for vaccinations, if I'm not in a hurry we take the streetcar to Orionka, where in those long- ago days it smelled beautifully [a large candy factory used to be located there], I take the steps down to Ruska [Street] then to Bulharska [Street], we lived on that one, we stop for a while and I look at our balcony, reminisce and in my mind's eye I see my mother there. I then take Bulharska to Kodanska [Street], along my usual route to school, there I also stop for a while, in front of it we non-Catholics used to play 'Odd Man Out' during religion class, and then it's only a bit further to Dr. Bondy's.

My parents were Communists. Apparently they brought it with them from the kibbutz, which was the only functional, real commune, functioning without a dictatorship of the proletariat, leading role of the Party, repressions, Gulag 15 or electrified barbed wire fences. They didn't know about what was at that time already happening in Russia, and if someone did claim something as sacrilegious as that, they most certainly considered it to be hostile capitalistic propaganda. And so they also brought us up in that spirit, we didn't go to Sokol 16 for exercise, but to the Federation of Proletarian Athletic Cooperatives, instead of Scouts to Sparta Labor Scouts, and in the summer we used to go to the pioneer camp in Sobesin na Sazave, where the indoctrination continued in an intensive fashion, what else. It was an infallible, uncritically accepted faith. The Holy Trinity was replaced by Marx-Engels-Lenin, Jesus the Messiah was replaced by Stalin. I can't otherwise explain succumbing to this religion, or rather delusion.

I don't believe that in those days someone would join the Party with an expectation of thus laying the foundations for the future acquisition of unlimited, uncontrollable power over people and the sources of society's riches, to be more equal among equals, but perhaps someone was so far- sighted. And even so, it can't justify that what some of these former idealists and those who joined them later perpetrated. Excuse me this digression from the subject at hand. Erase it if you want.

So after our return from Palestine, my father was involved, as far as I know, mainly in the so-called 'Rote Hilfe,' or Red Aid 17, which helped Communist, perhaps also socially-democratic refugees from Germany and Austria here. I've retained the memory of how once this one man came to our place, splashed about in our bathtub like a madman, and I asked my mother why he was making such a fuss. She explained to me that he'd escaped from a concentration camp, and that he hadn't had a bath for several months, and so now he wanted to properly enjoy it. After that he stayed for lunch and left. We had visits like that often.

Of course, as a member of the Communist Party, my father could have had problems at work. And so on 1st May my mother and Ruben took part in the Communist parade, and my father took me to Wenceslaus Square where we stood on the sidewalk and waved to them. I remember that my mother had a red kerchief on her head. Once, the next day our teacher asked me what we had done on 1st May. One zealous boy immediately put up his hand and told on me, that he'd seen my mother and brother in the Communist parade. But our teacher didn't praise him for this information; instead she gave us a lecture on democracy.

Immediately after the occupation 18 began the arrests of active anti- Fascists according to lists prepared in advance, and so during the first days after the occupation our father didn't sleep at home, occasionally he dropped by during the day, but for that we had a special signal: if there was a blanket hung out on the balcony, it meant that the Gestapo was at our place. I don't know if we would have had enough time to hang out the blanket, luckily our father wasn't on the lists, and so after the end of the wave of arrests he returned home. But even after that he worked illegally, that I know, he was part of an organization that arranged illegal crossings into Poland. Actually, believe it or not, even I, at the age of eleven 'worked illegally.' Several times my father sent me somewhere with an oral message. It was an exciting experience, but it could also have been dangerous, if the Gestapo would have been at that apartment at the time. How would have I explained to them why I was coming to visit strangers? But my father probably didn't send me where such danger would have existed. I don't remember the details any more.

At home we spoke only Czech, I don't remember recognizing that it wasn't my father's mother tongue. But it probably wasn't perfect, because in the letters that our parents wrote us to England, you could tell my mother's corrections of my father's grammatical mistakes. But she did it in such a way that it was almost unnoticeable. And there weren't many of them. You could probably tell it from his pronunciation. But at that age I didn't pay attention to it.

Well, I should tell the truth and nothing but the truth. For about two years, once a week, I attended private German lessons, and my mother got the idea that one day a week we'd speak German so I could practice. The idea was undoubtedly a good one, certainly I would have thus learned more and faster, that's proven by the fact that I then quickly learned English and German concurrently in England. There, of course, necessity was a great teacher. At home I always sooner or later gave up on it, and my mother probably wasn't rigorous and patient.

I don't know what else I can tell you about life before the war. Seen through my child's eyes it was a wonderful time, we lived a fairly modest life, certainly we weren't wealthy, I don't remember my parents raising their voices when talking to each other, or arguing, when later I used to see it with other married couples I was dumbfounded by it, I couldn't understand it, because I had never encountered it before, and didn't know that something like that existed. Something else was the relationship between me and my brother; there the sparks were always flying, as it tends to be between siblings, especially if there's two of them. Probably when there are more of them it's not like that any more, then that sibling rivalry and envy dissipates. It also stopped while we were in England. We could no longer envy each other our parents' attention.

My brother played sports a lot, so he never used to be home very much in the afternoon, while I, on the other hand, was a domestic type, what I liked most was to be with my mother, watch her cook and ask her about this and that, I helped out when she let me, after a big load of laundry I'd go down to the laundry room with her and help her put the laundry into the spinner, hang and take down the laundry, I regularly went with her once a week to Smichov, sometimes even on other visits. But probably I was also bad, occasionally my mother would chase me around the dining room table with a wooden spoon, probably I managed to escape many well-aimed blows after all. I really don't remember ever getting it from my father. Maybe also because he worked outside of Prague, he was an accounting supervisor, he checked whether the cartel members were observing the agreed-upon rules, and so on Monday morning he'd leave and return on Friday evening, and then on Saturday before noon he'd leave for the audit company he worked for, and most likely reported what he had found. I remember only one unrealized hiding, I escaped before him to the washroom and locked myself in, I was terribly afraid of being beaten, I resisted my father's threats that it'll be worse if I don't open, in the end Dad gave up.

And suddenly the idyll was over. Hitler's speeches on the radio, which my parents listened to, which while I didn't understand, I could tell from his manner of hysterical bellowing that it won't be anything pleasant, the occupation of Austria 19, Munich 20, the Protectorate. And when the danger could already be felt in the air, air raid drills began, sirens wailed and we had to go hide in the nearest building and wait until the siren sounded all clear. My mother joined the volunteer nurses; she bought herself a uniform and in the evening attended Red Cross classes. I remember my mother and I going to buy gas masks, they sold them beside Viktoria Zizkov [a soccer stadium in the quarter of Zizkov], I was very proud of mine.

On the morning of 15th March 1939, by then we already knew from the radio that President Hacha 21 had 'asked' Hitler for protection - I don't know from who - I was walking to school like always, like always I was walking through the Herold Orchards, and there, there were German soldiers lounging about, tremendously noisy and merry, self-satisfied, they had built a fire under a military cauldron and were cooking something for breakfast. And I also remember how they'd lay siege to sweetshops and with apologies stuffed themselves with whipped cream. I guess they didn't have it in the Third Reich. Or they made use of the very favorable - for them - exchange rate of 10 Kc per mark, which they established right on the first day after the occupation, and merchants were obliged to accept payment in marks.

One more reminiscence: One day, instead of going to class, we schoolchildren were obliged to go greet our first protector, the knight von Neurath 22. After the Germans, the Communist regimes also grew fond of this obligatory greeting activity. But by then civil servants, soldiers, militia members and who knows who else also went to greet. Our teachers led us to Smetanovo Nabrezi, in front of us on the hill Hradcany [The Prague Castle], where his eminence the protector had deigned to settle in, around crowds of schoolchildren drove cabriolets and gave out little paper flags with the swastika. The schoolchildren were throwing them down underfoot, we were Czech patriots after all, and back then we didn't yet know how afraid we should be, and so they brought another batch, and that repeated itself several times, Mr. Protector was late, we stood there for about three hours. And then a huge long parade drove by us and in the end we didn't even know which of those many uniformed men with loads of shiny oak leaf is the one that we came to greet. We didn't have the flags any more anyways; they were lying in the puddles under us. I guess we seemed to ourselves to be courageous heroes.

We must have known about the departure for England soon after 15th March, because I stopped taking German lessons and instead started taking English. Well, and after the school year ended we already started preparing for departure, we were supposed to leave on 1st August. An excellent adventure ahead of us, how else would I have had a chance to see England at that age. Anyways, it was only for a few months, soon either Hitler will fall, after all the Germans must want to get rid of him, and we'll return, or our parents will come to be with us. So why worry? Frantic preparations began, all sorts of shopping, every bit of clothing had to have our name sewn on it, so they could sort it out after washing. It wasn't until years later that I noticed that my quilted blanket had beading in one corner with AUERBACH written only partly, and into it was stuck a needle with thread; my mother must have left her sewing and then forgotten about it. Even trifles like this managed after many years to evoke deep sadness in the soul.

One Sunday morning in July, right when we were sitting in the kitchen having breakfast, a letter carrier rang at the door; he brought a telegram that said that we were already leaving on 18th July. I don't know why back then from the original large transport they chose 70 of us for earlier departure, the rest then still managed to leave for England on 1st August, but the next one, which was supposed to leave on 1st September, never arrived at its destination. According to rumors it did leave, but in Germany they turned it back. That day the Germans attacked Poland 23, a world war broke out.

When the telegram came, I began crying, because it meant that I'd be leaving my parents earlier than I had it fixed in my mind. And my mother couldn't stand it any more and also began crying. After that we were brave, or at least we tried to be, well, mainly our parents did. The train was leaving at midnight from Wilson Station, so before that our parents took us for supper to a fancy restaurant on Wenceslaus Square. I remember it as if it were today, because that was the first time I'd been in a restaurant. It was Vasata's Fish Restaurant with obliging waiters in tailcoats, silverware, etc.

We probably didn't sleep much that first night; there were children much younger than me there, who cried the whole night through. Still at night we crossed the border of the Protectorate, late in the afternoon of the next day we left Germany and were in Holland. Up to that time we weren't allowed to leave the train, we had food and drink for the trip from home. We probably didn't have any concrete notion of it as such, but suddenly we felt relieved, we felt freer.

Of Holland I remember that hardly anyone walked there, everywhere lots of bicycles, which is no surprise when it's all flat there. Late in the evening we arrived in the port, there they loaded us onto a ship, assigned us to cabins and finally we could stretch out and get a good sleep. And in the morning when we woke up, we were already in the English port of Harwich. So we didn't get anything at all out of the boat trip.

The train to London wasn't leaving until noon, so they took us to a playground, we played soccer. Well, and in the afternoon we were already in London, at the train station they led us off to some hall, and there our future guardians picked us apart. Mrs. Hanna Strasserova came to get my brother, me plus six other children, and took us to Stoke-on-Trent, a polluted industrial town of a quarter million in the center of England. I hadn't known those six children up till then.

It was like this: Hanna was a friend of my parents', they knew each other from the kibbutz. She and her husband and son had also returned to Czechoslovakia, they had lived in Teplice, where her husband was from, my mother and I had been to their place about twice to visit. My brother had been with them for a year on an exchange so that he would learn German, that used to be called 'tauschi,' their son on the other hand was at our place, to learn Czech. After Munich they lived in Prague not far from us, also in Bulharska Street, and immigrated to England already at the beginning of 1939. Over there Hanna probably found out about Nicholas Winton's endeavor, and so initiated the formation of the Czech Children Refugee Committee - North Staffordshire Branch, which put together people that wanted to help, to canvass for financial contributions for the advance deposit that the Ministry of the Interior wanted, before they would give Nicholas Winton permission for our stay, money for financing our stay and they also arranged accommodations. Then they also often visited us, invited us over to their homes, took us on outings and so on.

The town council provided a house that belonged to an orphanage - it was called the Children's Homes - it wasn't a normal orphanage, but what today is called a children's village: a fenced-off piece of land with gates always open, a dead-end street led in from the entrance, more of an avenue lined with large trees, at the end a huge playground, on both sides of the alley duplex houses, in each house a guardian whom the children addressed as Mother, and with her about ten children of both sexes between the ages of 3 and 14. So it was this large family, but without a father. So like in a family they also had to help out at home: sweep and mop the floor, wash dishes, peel potatoes, bring in coal and so on.

Well, and one of those houses was empty, and the city put it at our committee's disposal. And so the committee got housing, water and electricity for free, once a year the local mining company gave us a big load of anthracite, and the committee raised money for the other necessities. In the beginning it went well, later it was harder and harder; the war brought people other problems, union organizations, our main sponsor, had a much lower income, and probably were also helping the families of members that had joined the army. We also helped out in the household, I didn't mind that, I was used to it from home, Father cooked lunch on Sunday, he knew how to make only one thing, risotto with smoked meat, but that didn't matter, I always looked forward to it anew. Well, and after lunch my brother and I would wash and dry the dishes. Basically our mother had a day of rest on Sunday. I've digressed again.

I was afraid of the housework only when it was my turn to light the fireplace; there was no other heating there. It would go out a few times, the smoke went into the room instead of up the chimney; it always took a while before the fire wised up. But it was cold there anyways, unless you stood right by the fireplace, where you'd warm up one half of your body, and then after turning 180 degrees, the other half. What's more, single- glaze windows, and I, spoiled by an apartment with central heating. And they didn't buy me my first long pants until I was 15!

But the first week we were placed with families, as they had expected us after 1st August, and so preparations weren't finished yet. After we moved in, intensive English lessons began, as the school year was beginning in less than two months. We were taught by an Englishwoman, a retired English teacher, before that she had taught English in the Palestine, but she didn't speak Czech, so we learned with the help of pictures, pointing to things and so on. She probably already had it tried and tested, she must have taught us at least something, and so six weeks later we started school.

They let me repeat 5th grade, after a half year they judged that I already knew enough English, and transferred me to 6th grade, where I belonged age- wise. There I finished Grade 6 and 7, then I passed an exam for a two-year technical school, there I liked it, the teachers knew how to capture our interest, I finished it without any problems. With honors, even. I spent the last two years in England in a Czechoslovak state high school, which was financed by the Czechoslovak government-in-exile, where I on the other hand did have problems. Not due to Czech, that I hadn't forgotten, as opposed to many others, but with having to memorize boring subject matter, that I didn't enjoy. And so I just scraped through.

For some time we were able to correspond with our parents, but it took a long time, the mail passed through the hands of censors in England and Germany, plus we were sending it through friends in the USA, who were also former Bet Alfa kibbutzniks. In Prague my mother and I used to go on visits to their place. This was possible until the United States declared war on Germany, but even after that we stayed in touch for some time. There was the possibility of sending letters through the International Red Cross in Geneva, which was actually intended for prisoners of war on both warring sides, and somehow it was also made possible for us. It was very scant writing, something like a telegram, limited to 25 words besides the address, and we had to write in German. The reply was written on the reverse side. Where they took it to be sent, I don't know. I've got several of them hidden away, but likely not all of them, so I don't know when it stopped. Most likely in 1942, when our parents were transported to Terezin. No, it didn't seem strange to me, as the other children were also no longer getting these messages, and so I thought that the Germans had disallowed it, we weren't prisoners of war.

I didn't experience any bombing, just once a bomb fell on a nearby house and completely demolished it, most likely some German plane had been hit and needed to jettison some weight. But all the while, it was an industrial town, coalmines, machining companies and so on. But we experienced enough air raids during the Battle of Britain; practically night after night bombers flew over Stoke, aiming somewhere further north. Sirens would begin to wail, they woke us up, we quickly dressed and ran to a nearby air-raid shelter, which served the entire orphanage. Well, and when they flew over again on the way back, they sounded the end of the air raid and we could go back to bed. Quite often it even happened more than once a night.

So we didn't get a lot of sleep. But in the morning we went to school as if nothing had happened, with the obligatory gas mask, which you couldn't compare with the one I had left at home, unused. This one was stored in a paper box with a string sticking out, so you could carry it over your shoulder, and instead of glass eyeholes it had a celluloid oval. So I scorned that mask, but I had to carry it with me. Like everyone, even adults. There weren't any others available for civilians, but on the other hand, they were for free.

We were taken care of by married couples, also from Czechoslovakia, which every so often changed. Without exception their German was much better than their Czech, sometimes they didn't speak Czech at all, and so I actually learned German at the same time as English. But it wasn't nearly as perfect, I had a good vocabulary, but I would have gotten an F in grammar. Soon we got used to each other, I don't recall there being any animosities, arguments or fights among us children. Of course I found some of them more sympathetic than others, but that didn't prevent us from living in overall harmony.

They also organized us into a choir, my brother played the accordion and Ralph, who was one of us, the violin, and so we went about the town 'playing concerts.' What's more they dressed us up in something horrible that they had sewn themselves, and what the English were supposed to think was a Czechoslovak folk costume, I don't even want to describe it to you. They told us that it was propagation of Czechoslovakia, so people wouldn't think that we were from Africa, but most likely the main goal was a collection for the running of the home. But all the same, I have fond memories of that time.

Worse was the stay at the Czechoslovak state school, where I spent the last two years. One thing is ten children living together, and another is 200 children living together. I didn't like the loss of privacy, I can't comprehend why the English are so fond of their boarding schools. Maybe because it isn't all that cheap to send a child to such a school, that with the rich it's the fashionable thing to do, but they probably also think that their child will get 'hardened' by that environment. I didn't observe that in myself.

I spent four sets of summer holidays in Northern England on various sheep farms, I helped out here and there, in the last two years quite actively with haymaking. There were huge meadows with more or less freely grazing herds of about 800 sheep, they spent the night outside, and as snow is rare there, they partly grazed even in the winter and weren't dependent only on hay. But there was enough of it, we harvested it all summer. When it wasn't raining, that is. And that was quite often.

My brother was the oldest of us eight, and at the age of 18, in the summer of 1943, he volunteered for the Czechoslovak Army. After him, gradually the other boys, except for me, I was the youngest, I wasn't 18 until 1946. So towards the end of the war from the original eight only three of us remained, I plus two girls, who were younger than me.

Near the end of May, maybe the beginning of June, a letter arrived at school from my brother, who had in the meantime arrived in Prague with the army. In it he wrote that he hadn't found anyone in Vrsovice, so he had gone to Smichov, there he found Aunt Oly and Mirjam and Grandma, that Grandpa had died and that the only thing that was known about our parents was that they had been transported someplace from Terezin, and from that time on, nothing. He probably already realized, most likely from what Aunt Mirjam had told him, what fate had befallen them, which he couldn't bring himself to write me outright, and so I lived on in the illusion, or hope if you like, that they'd still appear out of somewhere. It must have been similar for the mothers and wives of soldiers, who got letters from the army command that they were missing and also for a long time hoped that they'd return, especially if they had been at the Russian front. Prisoners of war were still returning from there at the beginning of the 1950s.

Our return was organized by our government, and so one day at the end of August 1945 they loaded us, that is me and those two girls, onto an army airplane, probably for the transport of paratroopers, because we were sitting alongside the fuselage on wooded benches, not exactly comfortable. And without refreshments! At Ruzyne they put us on a bus and took us to the YMCA building on Zitna Street, which had been converted to a temporary dormitory, and gave everyone a bed. I put my suitcase under the bed, and went straight to Karlovo Namesti [Charles Square], got on the No. 16 and went to Smichov. Because I had always taken the No. 16 there with my mother. At that moment Andel was my only stable point in the universe. I went to the store, as I didn't know where my aunt lived. Only the assistant was there, whom I had already known before the war, and he gave me directions.

How many times in England had I imagined how I'd arrive in Vrsovice, look up at the balcony whether I would catch a glimpse of my mother, then ring the doorbell, my mother or father will open the door, shout out in joy and thus call the other parent. How we'll be endlessly happy, we'll enter the same river again and then it'll be nothing but a beautiful, idyllic life...

It ended up differently. I rang at my aunt's door, a tiny old woman came to open up, I said good day, and asked if Mrs. Dvorakova was home, the old lady said that she had gone shopping, that she'd be back soon, and then I and Grandma recognized each other at the same time, and hugged. Grandma took me into the room, we sat down and Grandma began crying, with joy and pain at the same time. And then she only repeated, and this very often until her death, 'Why didn't I die instead?' From that time I know that for a woman there is no greater pain than the death of a child. The day that Grandma was dying, my aunts and I visited her in the hospital. She was in a morphine-induced delirium, didn't recognize us, and just repeated 'Gretinko.' That's how she addressed her daughter, my mother.

I occasionally borrow some English book in the local library, so as not to forget completely, what if it could come in handy one day. The last time I borrowed the autobiographical novel 'Sons and Lovers' by D.H. Lawrence. In it he writes about the death of his older brother, about his mother's sorrow, how she constantly repeated, 'If only it could have been me!' So my grandmother's reaction wasn't unusual.

After about half an hour my aunts returned from doing the shopping, once again joyful greetings and hugs. Mirjam decided that we'd immediately go to Zitna for my suitcase, and the very first night in Prague I slept at my aunt's in Smichov. I lived there for two years, until I graduated from high school. My bed was in a room which was at the same time the dining room, you walked through it from the foyer to the living room, bedrooms and washroom, so there was no privacy. Of course it was better than living in an orphanage, which happened to many, including those two girls that were in England with me.

Once I was in that Jewish orphanage with a classmate to visit his brother. It was a horrible experience, which enabled me to realize how much better off I was, and to perhaps not feel so sorry for myself. But even so, my return home was incomparably sadder than my departure for England. Back then it had been a time of great hopes, or rather certainty, that we'd soon see each other again. But life had to go on, so I went to the nearest high school and scraped through the remaining two years before graduation. After graduation some classmates and I left for three months to help farm in the depopulated border regions. Back then it was allegedly a precondition for acceptance to university, many sneezed at it and they accepted them in school anyways. But I don't regret it, it was also one of life's experiences.

Back then Aunt Oly's husband had already expressed an interest in my moving out. At that time Aunt Mirjam had already moved back into her original apartment, which surprisingly was free. It was on Bulharska Street, so several buildings over from my pre-war home. She found me a sublet in that building and so I moved there. I was badly off in terms of finances, I had an orphan's pension after my father, less than 600 crowns, and on top of that from the Joint American Jewish organization 24 I got 1000 crowns a month via the Prague Jewish community. That's about 2000 in today's crowns. But during the week I went to Smichov for lunch, usually I had supper with Aunt Mirjam, so in this way I managed. Within four years I finished statistics at CVUT and started working in power generation, I've worked in it in various economic functions my whole life.

No, I didn't have any problems at work due to the fact that I'm a Jew, even though it was generally known. How could it not be, when I've got such an exotic name, which many wondered at. Those were more due to the fact that I wasn't in the Party, which of course had an influence on my career, in that I was no exception. Occasionally someone said to me that if I would be, then I could... but for me it wasn't a sufficient reason to apply for membership. When in 1954 after my army service they outright offered it to me and gave me a membership application to fill out, I did take it home, but after a few days I politely declined, that while the idea of socialism is near to me, after all as a Jew I can't and won't join a party that expresses anti-Semitism. It was not long after the trial with Slansky 25 and his band of Zionist conspirators, oddly enough they understood my position. They never bothered me with another offer.

In the spring of 1950 I married a girl that I had been going out with since my last year of high school, near the end of the year our first son, Ivan, was born, and in 1956 a second, Pavel. Both did well in school, they studied engineering, the older one mechanical, the younger electrical engineering, both are married, Ivan has two children, his daughter recently finished university, civil engineering, last year his son started university, he's studying architecture. They younger, Pavel, unfortunately has no children. They wanted them, but it didn't work out. But my sons feel that Jewishness is a part of them, but don't devote themselves to it in any particular way. And why should they, when even their 'purebred' father doesn't live it. Once Ivan proclaimed in front of us, I don't even know in relation to what any more, that he's more proud of his Jewish half than his Czech half, which warmed my heart, and nettled my wife. But surprisingly she didn't react to it; she ignored it, as if she hadn't heard it. That was quite unusual.

So what remains now is to say something about the further events in the life of my brother, Ruben. Those were somewhat less straightforward than mine. After being discharged from the army he moved to Brno, where he had an army buddy who had gotten an apartment there, so he lived with him, attended college and in the summer of 1946 graduated. He started working in Teplice, I don't know why he picked Teplice, maybe because he'd once been there on 'tauschi.' He didn't deny his Communist convictions from his youth, joined the Party, maybe also because he considered it to be our parents' legacy, and was very active. He wanted to blend into the majority of society, and so he changed his name to Pavel Potocky. But for the rest of his life we all that were near and dear to him called him Ruben anyways. I didn't follow him, because for me my only inheritance was my name, and my task was for them to continue through me. I didn't follow him in joining the Party either, not because I didn't believe in the ideals of socialism, but more out of inertia, dislike of organizations and associations of all kinds.

I was sorry that he had changed his name, but I didn't say anything to him, he was my older brother, so what right did I have to criticize him, I just said to myself that if it really had to be, he could have chosen our mother's maiden name, Fantl, which doesn't sound German or Jewish. Apparently it's the name of Sephardic Jews 26, those are the ones that came from Spain. Allegedly my grandfather's ancestors came from there. Mirjam once told me that after our return from Palestine our mother wanted to change our first names, and I was to have been Karel. But back then it wasn't possible, only to change German surnames to Czech ones. That is, after the creation of the Czechoslovak Republic 27 in 1918, when it became 'in.'

I'm digressing again. So as I've already said, my brother was very active in the Party in Teplice, and so they decided that he's what they called a cadre with good prospects, and that he should continue in politically educating himself. This took place at the Lidovy Dum [People's House] on Hybernska Street, once and now again the headquarters of the Social Democrats. A boarding school, where he spent the 1949/1950 school year. Then for about a half year he was some sort of junior official in the party apparatus. But by then the party purges had begun, suspicious were mainly those that had fought against General Franco in the Spanish Civil War 28, those who had been in England during the war, and as it's been the case for centuries, Jews. My brother satisfied two criteria, so they politely told him that he should go and work among the working class, to get to know it better 29. Well, it could have also ended up worse, they could have made him into an anti-state conspirator. But he'd probably been there too short a time for that, and hadn't come into contact with those up top.

He left for Ostrava, worked as a miner underground for two or three years, lived with other brigade members in wooden barracks, so more with the lumpenproletariat than the proletariat, I don't know any more how many of them there were to a room, he had a bed and a small closet, nothing more. In 1951 I was in Ostrava on business, so I made use of it and went to the dormitory, which quite shocked me. After several years he returned to Prague, he used to commute to Vodochody, where they manufactured jet fighters, he worked there for several years as a locksmith.

When in 1956 the Soviets sent the army into Hungary 30 to suppress the rebellion, it was the proverbial last drop and he left the Party. Back then it was no joke, they summoned him to the committee perhaps ten times and tried to convince him with various 'arguments' to stay faithful to the Party, they were annoyed that a member of the working class was leaving the Party, but he insisted on it, so they finally let him go. He was very stressed out by it.

After some time he found work in Modrany, the daily commute to Vodochody was very time-consuming. In Modrany he also worked as a locksmith, and then for some time as a technician, so he could finally make use of his education. He married, had two children and in 1969 immigrated to the United States. After 1989 he came to Prague once with his daughter, she's also Mirjam. When I became a widower I visited them, that was in the year 2000. My brother died two years ago.

There he didn't have it easy either, especially the first few years. In the beginning they lived in New York, then they moved to Denver. He found work as a technician, his wife worked in a clothing factory as a seamstress, their daughter finished university and is now a university professor in Miami. Their son didn't want to study, he took after his father in some things, he changed his name from Jan to Michael, and at home they call him Honza [a familiar version of Jan] anyways, he's a truck driver, single and still living with his mother. Which is actually good, because otherwise she'd be alone, even after so many years her English is miserable, she never got used to living there, but neither did she want to go back. Her adult children would for sure not return, so that's probably why. They've got a nice house with a garden and a paid-off mortgage.

So that's perhaps all about our family. I told you right at the beginning that there was nothing particularly interesting about us that would be worth writing down. There were more dramatic fates; those are more the ones that should be remembered. But in many families no one remained to tell their stories.

So now you want me to say something about our family's relationship to religion, to Judaism in the wider sense of the word, to traditions. We were almost all atheists. My grandfather on my mother's side was deeply religious, he attended synagogue daily, morning and evening, to pray, during the Sabbath he stayed there almost the whole day, he was a member of the board of elders of the Smichov synagogue and a member, perhaps even the chairman of the funerary brotherhood, which in Jewish communities take care of the last rites. Its members go to pray with the dying, after death they dress him in a shroud, lay him into a coffin, and if he was a pauper, they would pay for the funeral from the contributions of fellow believers.

I experienced a Jewish funeral only once, the funeral of my grandmother from Smichov in 1954. At that time I was taken aback that she was being buried in an ordinary box cobbled together from rough, unfinished planks, at first I was scandalized, I thought that my aunts had wanted to save money on the coffin. Then I realized that it's a Jewish custom expressing the idea that we're all equal at birth and at death. But that doesn't count for gravestones. Through those wealth is expressed the same as in Christian cemeteries.

Perhaps only Grandpa's son Rudolf was also a believer, but for sure he wasn't as frequent a visitor to the synagogue. I don't even know how it was with Grandma. During Grandpa's lifetime she most certainly observed certain habits, women however traditionally don't pray as much as men, they don't have time for it, when they have to take care of the household while the men are off somewhere philosophizing and arguing about the meaning of this or that biblical passage, they aren't even allowed in the prayer hall, they're only allowed into places specified for them. While men from times immemorial have learned Hebrew so that they could read holy books and discuss them, their wives remained illiterate probably until the institution of compulsory schooling.

So I didn't encounter my grandmother's religiosity until after the war. Once a year, on the Day of Atonement, she spent time from morning to the late afternoon hours in the Jubilee Synagogue, that's the one on Jeruzalemska Street, the whole day she'd fast in accordance with religious decrees. With Jews that means not only not eating, but also not drinking. Aunt Oly was concerned that at her age she could faint on the way home as a result of this, and so I'd come for her before the end of the services, I'd wait in front of the synagogue and accompany her home. Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah, or New Year and the Day of Atonement are the so-called High Holidays, and during these days many Jews who otherwise don't visit a synagogue all year and don't pray much at home either, and probably even many unbelievers fill synagogues all over the world. It probably strengthens their sense of belonging to Judaism, even though otherwise they try to assimilate and blend in with the majority of society.

Nevertheless, the complete family did gather together one day a year, which was for seder, a celebratory supper commemorating the departure of Jews from Egyptian slavery. This supper has a very strict, exactly defined ritual, the youngest member of the family asks the oldest member of the family specific questions that are always the same, and each year gets exactly the same answers to them. I was the youngest one, I remember that my grandfather was sitting at the head of the set table, I on his right side along the longer side of the table, and I'm asking him questions in Hebrew that they taught me in religion class, he answers me in Hebrew and I don't understand him but know what he's talking about, the rabbi explained that to us during religion class. Everyone was smiling at how beautifully I said it, I had a book in front of me, in which the questions [the mah nishtanah] and answers were written, in Hebrew of course, but I had to memorize them, otherwise I would have stuttered and stumbled through them.

I went to synagogue once a year, but not on the Day of Atonement, it was during a holiday when children would walk through the synagogue, each one with a borrowed flag with the Star of David [Editor's note: it was the Purim holiday]. As we walked by the board of elders of the synagogue, who were sitting in front of the box with the Torah, the board members would give each of us a bag of candy. My grandfather also sat there, and I was proud of him.

I was at the synagogue one more time, I know the exact date, it was on 1st January 1938, my brother had his bar mitzvah, as the day before he'd turned 13, the age at which a boy enters adulthood, and he was reading from the Torah the prescribed text for that week. A bar mitzvah is a great event in a Jewish family. Whether he knew how to read it or he had memorized it, I don't know. I didn't have a bar mitzvah, if I would have wanted it, I could have had it in England, in the Czechoslovak state school we had 'our' Czech Catholic priest and rabbi and a small prayer room. I think that Catholic and Jewish services alternated in it, most certainly he would have gladly prepared me, but I was proud of my atheism. Today I regret it; it belongs to Judaism as inseparably as circumcision, so I feel the poorer for it.

Believer or not, I did attend religion class, it was always once a week in the afternoon in the school, we gathered there from several grades, and the cantor from the synagogue in Nusle taught us, I guess there wasn't one in Vrsovice. He was an older, tall thin man, very tolerant, almost all of us came without a yarmulka, we didn't have them, and so during prayers at the beginning and end of the class - 'Sh'ma Yisrael Adonai Elohaynu Adonai Echad.' [Hebrew: 'Hear, Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One'], I don't know the rest any more, one also began with 'Barukh ato Adonai' [Hebrew: 'Praise the Lord'] - we put our palms on the top of our heads, and thus overcame this handicap. With a smile he'd ask us if we'd had pork with dumplings and sauerkraut for lunch, if yes I told him, at that time I didn't even know that I wasn't supposed to eat it [because of the kashrut, the body of Jewish law dealing with food that dictates which living creatures are allowed to be eaten, and which aren't. Pork is a forbidden food]. But he just smiled and didn't comment on it. He'd then tell us Bible stories, before the beginning of holidays, why we observe them.

He also tried to teach us Hebrew. In that we didn't excel, I don't think that we got any further than reading the primer, of which I remember only the first page, or in your case the last. It had a drawing of a garden and under it in Hebrew, GAN. He only ever really got upset when we with difficulty pronounced the word 'yeyo' in the text, which doesn't mean anything, Jews use this to get around writing God's name, Yahweh, which is forbidden. I suspect that we were looking forward to how upset he'd get, and never forgot to say 'yeyo.' Why did I, at home raised as an atheist, attend religion classes? For the same reason that my brother had his bar mitzvah: because of Grandpa. And it didn't bother me, nor did it do me any harm.

Otherwise we didn't observe any Jewish traditions, not even eating kosher. I've already told you, after all, that on Sunday my father would regularly make a risotto from smoked [pork] meat, I loved bread with lard sprinkled with cracklings, that was some delicacy! I don't know, but maybe even in Smichov they weren't so strict about it, besides seder that is, that they would eat matzot instead of bread for the whole of the Passover holidays. Why do I think this? When my mother and I were there on our weekly visit we'd be there until evening, and so I'd have supper in Smichov. They'd give me two or three crowns, I don't know how many any more, in the summer they'd send me to the neighboring store, a dairy, and there the lady would pour me a cup of milk, with that two rolls and a triangle, perhaps two of Swiss cheese, she had a table there at which I'd eat it. But in the winter they'd send me to the deli on the corner for a wiener with mustard. And that's not exactly kosher. But sauerbraten with cream sauce, that I didn't taste until after the war.

So my mother probably didn't know how to make it, as at home they didn't teach her how to make it, meat and milk can't be together in one food, in fact there should be separate dishes for meat and dairy foods. During biblical times there weren't any refrigerators and with the temperatures in the Middle East being what they are, that was reasonable, no? Otherwise we probably ate what everyone else did. I liked stuffed [with smoked pork] potato dumplings with sauerkraut, stuffed sweet buns, those Mom would bake the day before laundry day and we'd then have them for lunch. I loved bread dumplings with eggs, that used to be for supper. I can still see before me how my brother and I are sitting at the table, and I'm stealing them from his plate, and right away there was a reason to brawl.

No, we didn't even have Christmas at home. Most likely I asked about it at home when my friends were telling me about Christmas supper and presents. But at home they apparently told me that Christians have Christian holidays and we Jews have our Jewish holidays. I guess that satisfied me, because I know that I didn't envy my classmates their Christmas. I was satisfied by this logical explanation. Even though later I found out, to my amazement, that some Jews celebrated Christmas precisely because they didn't want their children to feel left out.

But I didn't miss out on Christmas completely. The employees of the company where my father worked used to get a carp from their boss. A live one. But Father couldn't bring it home, as during the week he was away from Prague. The company's headquarters were on Ve Smeckach Street, and so my mother took a mesh bag, an old towel and me, and we would go to get it. There in the office they had a wooden tub, the kind they fish carp out of on the street before Christmas, they fished one out, wrapped it in the wet towel, put it in the bag and we took it home. And then he had to just sit in the bathtub and wait until Father came home on Friday and carried out his death sentence. But for sure we didn't wait until Christmas Eve to eat it. We probably ate it right that Saturday or Sunday. I don't remember how my mother used to prepare it.