Rozalia Unger

Szczecin

Poland

Interviewer: Anna Szyba

Date of interview: December 2005

Mrs. Unger is a cheerful, nice old lady. We meet in her tiny apartment in Szczecin. The single room is very modestly furnished. A large picture of her children hangs on the wall. Mrs. Unger is convinced she has nothing to say, but she still welcomes me warmly. Though her answers are laconic, as that is her way of talking, I still find many stories worth recording in her account.

I was born on 30th July 1917 in Cracow, but I grew up in Rzeszow [a town ca. 160 km east of Cracow]. I come from a working-class family. My mother’s name was Malka Achtman, née Szapiro. I know nothing about my mother’s father, her mother’s name was Bajla, and she lived with us. [I remember] grandma as an old lady, she barely walked. She was religious – always wore a kerchief! For Yom Kippur, she wore that bead thing on her head to commemorate the holiday. She died in Rzeszow, when the started transporting Jews away for liquidation 1, she couldn’t walk so the Germans shot her in the street.

My mother had two brothers. Their last name was Szapiro, but I don’t remember their first names, neither one’s. One [lived] in Zawiercie [a town 50 km east of Katowice], and one in London. I have here a photo [of one of my maternal uncle’s family] that we found in England after the war. My mother was still young, she was 47 when she died [so she was born around 1895], they were older. I don’t know where my mother was born, I know they lived in a place called Szczekociny [a small town 80 km east of Katowice], it was somewhere in Silesia, near Sosnowiec, or thereabout.

The [maternal] uncle who lived in England had emigrated there a long, long time before the war, to work, most likely, he was a cap maker. He sent us English pounds to provide for the family. He was very religious, reportedly had eight children in London. I’ve never met them. I don’t even know whether his wife was Jewish. I suppose so, because it’s typical for Jews to marry only with Jews.

My mother’s second brother was a hat maker. He was very religious too, and I remember, after I had been released from prison [ca. 1934], my mother sent me to Zawiercie [a town 270 km south-west of Warsaw] to him, his wife, my aunt, met me, but I had a sleeveless dress, and Jews aren’t allowed to bare their arms, so she gave me a scarf so that I could say hello to him, because I have bare arms so he won’t talk to me. They had no children of their own, only two adopted girls, Jews. I knew they had been taught to sew, to care for themselves, perhaps they were earning for their maintenance that way, I don’t know. I remember they lived on the second floor, in a brick house. And the shop was there too. I don’t know whether Aunt worked too. I remember nothing from Zawiercie either because I was there for only a very short time – just a couple of days. I know the older daughter once took me somewhere to some people to entertain me. But I didn’t open my mouth, one thing that I was young, the other that those were people I didn’t know.

I know little [about my mother]. I don’t know whether she went to any school, I’m afraid she could neither read nor write, but I’m not sure. She had to provide for four persons, because I don’t remember my father, he reportedly went missing. Above all, I remember my mother selling a lot of things in a pawnshop to provide for us, and I no longer see those things. There was that plush tablecloth, maroon-red with golden stitching. The same thing on the beds and on the table. And on top of that was also a kind of mesh, the whole thing was obviously valuable, because she sold it. But generally what did she do for a living? It depended, but, as I understand it, she grabbed every opportunity that appeared. I remember, for instance, that she dealt in fruit: if someone had an orchard, a couple of trees or a whole orchard, she’d make a deal with them in the spring or in the autumn, I don’t remember, and when the fruit were ripe, she’d have them picked up, she didn’t do that herself, and sell them; the retailers bought from her.

There were, I remember, those tiny little apples, called the ‘cocks,’ and she’d rent a cellar from someone (we had a basement, but it was no good for that) and pickle cabbage there, and those apples in that cabbage, they were the best variety for that. When already pickled, those apples had a sort of gas in them, very refreshing, like soda water, and flavored. People came and bought it. There was a whole barrel of the stuff, I remember once the barrel was so large they couldn’t take it out of the cellar and people went down there and [bought] as much as they wanted. Those were the sort of things we lived on, but the money from that was just pennies, really.

My mother was religious, but already adapted to the modern times, because otherwise it would have been hard to survive. She lit the candles on Friday night, wore a wig on a Saturday, but not everyday, so she wore a kerchief, because you weren’t allowed to show your hair. I know she went to synagogue, but only for the high holidays, that was obviously a religious dictate, there was a separate space for women, a separate one for men. I see the synagogue in my mind’s eye, but I don’t remember the address 2. I think I never visited the place, you didn’t take children there, I guess, and later I was a communist, so it would have even been a dishonor to go to a synagogue – we were atheists.

My father’s name was Salomon. I know nothing about him to this day, I didn’t know him at all. I know nothing about his family either. I know only that once [my mother’s] brother came, whether from England or from Zawiercie, to attend to the formalities associated with [my parents’] divorce. But I was a kid, no one cared about me, asked or told me anything.

There were two of us, the kids. My brother was a year and half younger than me. His name was Mojzesz, a Biblical name, and I was Biblical too, my name was Rachela. There was nothing to play. He was in the cheder, he went there every day, but he wore no payes. I don’t know where he went later, certainly some elementary school. During the summer holidays we did nothing, and what could we do, no one organized any kind of shows or activities for young people – there was nothing of the sort! There were no summer camps. Who ever spoke of a summer camp? It was good if we had enough to eat at home.

Then [my brother] went to work, he was a bag maker, he went to Bielsko-Biala [a town ca. 60 km south of Katowice]. He worked there for a German Jew who had been deported before the war back to Poland 3, he was a bag maker, had a store, had some money, set up a shop, and gave [my brother] a job there. The two of them regularly went to France to buy new things, bags, suitcases, tools.

We lived in Rzeszow at 5 Lwowska Street. It was a tenement house, but in the back. The owner was a Jew, and the janitor a Pole. The apartment had one room, a large one, so we divided it up in half: two beds. My brother had his own, because he had to sleep separately, and I slept either with my mother or my grandmother. And that was it: a kitchen stove, a table. There was no bathroom, no one had a bathroom, typically there was even no running water, but as far as we were concerned, I remember my mother had a deal with the next-house neighbors who had a well, and if you wanted to use the well, you had to pay, but I think my mother didn’t pay, simply because there were two kids, and the grandma, for her to provide for, so [the neighbors] didn’t charge her.

There was a workshop in the yard, the employees were Poles. A scrap dealer, the owner was a Jew. I don’t know what they did in that workshop, I wasn’t interested. Lwowska wasn’t solely a Jewish street, it ran down to Wislok, the river. Opposite [our house] stood a Polish elementary school, a single-story building.

The pre-war Rzeszow was a small town, very many people were jobless, there was a lot of poverty. Life was hard, poor, simply. I remember one [man] who had a store, on Panska Street, I think it was, selling bathtubs, water closets, obviously for those building or renovating their house. So there were people who could afford that.

There were stalls, stores, tiny ones, I remember a little store that sold a bit of everything, and next door there was a beautiful Christian store, the wooden floors were greased, whether with wood tar or some brown polish, so the peasants, when they came to do their shopping, with those cloth bundles on their backs, instead of going [to the Christian store], they preferred to go to the Jewish one, lest they spoil the floor [in the elegant one]. My mother sent me to the Jewish store to buy things on credit, whatever we needed on an everyday basis, whether flour or sugar, I paid nothing, only my mother would come after some time and pay the bill.

We spoke Yiddish at home. But I speak it no longer. Have no one to speak it to, forgotten. I understand it when spoken to me, but I can’t speak or read it. We spent the holidays at home, because we had no other family. My mother observed all the holiday rituals, today it makes me laugh, the division between the milk and meat dishes, the whole thing. The kitchen was absolutely kosher! It couldn’t be otherwise! They would have cursed [my mother and grandmother] if they had done that, but they were used to that, everyone did that so they observed it too.

For Easter [Pesach], you had to change all the dishes. And we kept the holiday dishes, unused, separately in a chest, and if someone didn’t, they had to scald the everyday ones, and then you could use them for the holidays. They lived the Jewish way, simple as that! But being strictly religious – no, that wasn’t the case. And especially when I was already able to tell, after I had been released from prison, I remember a situation once, you weren’t allowed to touch money on Saturday, and my mother once noticed me touching it, and she said nothing. That meant she had already adapted herself. She preferred to pretend she had seen nothing rather than reproach me.

I remember the peasant strikes, I could have been 9 or 10 at the time, then the funeral of Orbach [a less known communist activist in the 1930s], a Jewish funeral, and the communists pulling the covering off [from the coffin], people carried the coffin on their backs, and covering it with a red cloth instead. I remember a massive crowd, because the way to the Jewish cemetery was down our street, Lwowska, and people [lost] a lot of money, they were hiding in the gateways, I don’t know whether it was from the police or for some other reason, and I went picking up that money, those pennies. Orbach was a communist, they killed him in prison, punched his lungs. I knew his younger brother. It was the time when Pilsudski 4 set up the camp at Bereza Kartuska 5 and there, in Bereza, Orbach’s younger brother caught tuberculosis, I don’t know how, whether they beat him or whatever happened there, whether it was the food, enough that he had developed the tuberculosis and was released. I remember money was being raised among young people to pay for a sanatorium for him in Krynica or Zakopane.

I completed seven grades in a girls’ school, a mixed one [for both Jews and Christians]. We played all together, there was no problem. There was a religion teacher, a Jewess, religion was taught in Yiddish. There were [also] schools for boys, nearby, on the same street, I don’t know how it was there, my brother went there. Upon completing elementary school I wanted to go to a business high school, but that cost something 45 zlotys, my mother told me, ‘Write your uncle in England, he’ll send you the money,’ and that ended the story, he was supporting us anyway.

I went to work, for three years, to learn a trade. The people that gave me the job were Jews, and they were also communist sympathizers. There was some favoritism involved. I worked in a private tailor-making shop, we sewed dresses, blouses. I worked there as an apprentice. And other girls worked there [too] simply for nothing. Why for nothing? Because they wanted to go to Palestine, to Israel, and they needed a profession. They usually didn’t speak Hebrew. Young people generally didn’t know the language, few did. The religious Jews learned Hebrew, I don’t know whether they knew what the prayers they recited meant, whether they understood the words – this is something they know, but young people weren’t religious, like they aren’t these days.

I joined the party 6 because the economic situation, the living conditions in a way segregated us, made us part of a certain sphere, even though in the party – I was in the youth organization – there were also students from well-off families, cultural, educated, up-to-scratch people. (I didn’t think about joining the Jewish party). The Bund 7 had similar principles but a different goal. We worked with the Poles and the Jews, both were represented in the party. I remember no anti-Semitic behavior; there was nothing of the sort between young people. We were all equal, none of us had anything.

The meetings were all hush-hush, each time in a different place, at somebody’s home. Above all, we studied. We couldn’t have books because we might get caught, but there were educated people who knew how to pass knowledge on to us. [Everyone had their responsibilities] and mine area of responsibility were leaflets for the military. I don’t know where they printed the stuff – you weren’t allowed to know, it was top secret. Those were leaflets they distributed among soldiers. They spoke the truth – I don’t remember precisely what they said, it’s too many years, but they spoke the truth about the situation in the country, about poverty, indigence. My job was to deliver [those prints] to the military barracks. I faced a very harsh prison sentence if I got caught. My military contact, his name was Rajber, is dead now. They organized 1st May demonstrations [May Day, a holiday established by the Second International, celebrated annually with mass rallies, demonstrations, and marches], but on a very low key, and I don’t remember how it looked like. I remember pasting up posters on the wall, whether for 1st May or something else.

When I was 17, they arrested 36 people from the past. This could have been 1934 or 1935. Somebody betrayed us. I don’t remember who it was. I met my husband during the trial; he got two and a half years and served it. I also served time, but they released me after a year because I was the youngest.

We did time in Rzeszow, then they moved us to Tarnow [a town ca. 75 km west of Rzeszow], it was the time of the peasant strikes. I remember looking out of the window and seeing how they drove their wagons, with the torches, in the night. I was in a cell with other women. They treated us better or worse. They didn’t really beat us, but the boys they did. There, in front of our windows, was a boulevard. People sat there. And we shouted, when the guards started beating the boys, for them to stop. So that the people knew how things were.

They released me before Easter, and after the holidays the trial began. I remember [one of the defendants] was sick in his lungs, had tuberculosis, and someone from his family gave me a ham sandwich for him. Two slices of bread with a lot of ham in between, and I brought it to the courtroom and gave it to him.

After the trial I spent a couple of days in Zawiercie, because my mother sent me there to stay with the brother [of hers], to isolate me. But there was no work there so I packed my things and left for Cracow. I remember I paid 8 zlotys for a room I shared with another [girl]. I don’t remember where I knew her from but she was a communist too. In Cracow, I lived in various places. Above all, you had to pay. Not much, but the places weren’t special either. I remember I once shared a room with a girl who worked in a creamery below and I couldn’t breathe because of the lactic acid, and I found out it was her who had soaked through with it. The owner was a religious man who liked to peep at girls washing themselves. His wife knew about it and stood by the sink to cover us. He must have been after a stroke – he had a limp in one leg and a stiff arm.

I was an illegal, unregistered resident in Cracow. There was an organization there [Patronat, founded 1908], run by Sempolowska, I guess, [Stefania Sempolowska, 1870-1944, teacher, activist, involved in organizing aid for political prisoners, harassed by the authorities] that helped political prisoners, distributed foreign aid, from France, things that people needed. I received a pair of shoes, light-colored ones, very nice, oxfords.

I spent perhaps two years in Cracow. When there was work, I worked. I once worked for a tailor that made vests and my job was making the buttonholes, and to this day I can make a very nice buttonhole. The better I performed, the more money I got, but those were only temporary jobs. I wrote to my mother, sent her 10 zlotys from time to time. My brother also kept in touch with her like that [sending her money].

Then my husband came and we moved in together [Mr. and Mrs. Unger got married during the war, around 1941], there was a bridge beyond the Planty park, and beyond the bridge was Grzegorzewska Street, and there we lived at no. 8. The apartment had three rooms, and the owner, an obviously impoverished Jew, sold shoes, had a store somewhere, the store eventually move to the apartment, and he sold there, and one room he rented to us. We paid for that room, but then the war broke out and we left the place. I took the pillowcase, stuffed whatever fit inside, the basic things, and off we went. You thought it was just for a moment, that the war would not last long.

My husband, Oskar Unger, comes from a village near Rzeszow called Lubenia [15 km south of Rzeszow]. He was born in 1912, I guess, in peasant Jewish family, there were thirteen children, that’s the way it was those days; Jews didn’t do abortions. I knew my husband’s parents, the father was very religious, carried a beard, but that’s not what I mean but how he lived. They lived in the countryside, and throughout the countryside wandered people, religious ones too. I don’t know whether it was in the name of God or whatever. But if someone came, you had to give him food, water, whatever, and give him a place to sleep for the night. [My husband’s father] had a special little room for that and he never told the pilgrim to go away but slept him there. He even gave him food to eat, those were the customs, different than today.

They had two acres of land, one cow, and thirteen children, one looked after the other, and of all that the only ones to survive were my husband and an orphan boy [my husband’s] father had adopted, his name was Alman Intrater. [My husband] completed only four grades, that’s all there was in the countryside. [They were poor, my husband told me] how he walked on foot from the village to the city, he had a pair of shoes his father had bought him, so he carried them on his back and only upon reaching the outskirts did he wash his legs, put on the foot wraps, put on the shoes, and went to the city. And the same thing on his way back. He didn’t want to wear the shoes his father had been promising him for several years and finally bought him.

We fled, some people went to the station, to the trains, while we went on foot, and many people walked with us, back from Silesia, I guess, some teachers, we walked along the Vistula bank, and there was a house, and besides the house lay our Polish soldiers who had been mobilized to fight but had received no order and didn’t know where to go, what to do, and they lay in a row because they were exhausted 8.

And so, walking along the Vistula, we reached Rzeszow, and in Rzeszow I moved in with my mother. And on our way, a barber went with us, a Ukrainian, and he tells [the men], ‘I know the way, let’s keep going.’ [And my husband went with them]. On the way one of those boys decided to make a detour to Mielec, I think it was [a town, 60 km north-west of Rzeszow], he told them, ‘You go, I’ll catch up with you, I’ll only drop by, I have relatives there.’ And when he caught up with them later, he told them his neighbors had chased him away. [They told him] ‘Look where your people are.’ There was a hole dug out by the road, covered with lime, blood was soaking through, the earth was moving, and he ran away. And they went as far as Lwow. And from Lwow [my husband] sent me a letter to come as soon as possible with his brother and his brother’s fiancée, and we set off all three, but this time we hired a horse wagon to get us to the Bug.

And I remember that we happened upon some German troops marching down the road, and [my husband’s] brother was scared and hid in some house. We were also scared that they would take our horses away, but they didn’t, just marched past us, so he went out of that house and we kept riding up to the place where we wanted to cross to the other side, it was the river Bug, but how to cross it? We had some money on us; especially my husband’s brother had some. We went into a house, a Ukrainian man lived there; he must have spoken German because otherwise we wouldn’t have been able to communicate. There was a manor there, and in the manor stood the NKVD 9, and there were German troops. The others were afraid to get in. It must have been my young age that I was bolder than then others, I went in and first of all I told the Ukrainian that we would pay him if he got us through. I went to the NKVD, a tall, handsome German came out, with that bird on his hat, and says to us, ‘here, on this side, are the Germans, there, opposite, are the Russians, with all the equipment, if the Germans see you, they’ll start shooting.’ [After 28th September 1939, the territories immediately west of the Bug River found themselves under joint German-Soviet occupation. Soviet troops later left the area as a result of the so called second Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, in return for transferring Lithuania to the Soviet sphere of interest.]

The German and the Ukrainian went with us to the river bank, to a ford, we paid the Ukrainian 15 zlotys, and when we were crossing the river, I lost my fountain pen and the rest of the money that I had hidden. We waded in, and there were slippery stones. Water up to here, and I cannot swim to this day. Whether the others could, I don’t know, but we pushed ahead. All wet I eventually reached the other side, we climbed up that high bank on all fours, like apes, we stood there, and no one comes to us, no one asks us anything, nothing, so well, if there’s no one, then off we go.

We went to a peasant; he gave us a place to sleep. They told us to get inside, they were Jews, and it was Friday night or Saturday, some kind of a holiday, they fed us, gave us a bed, we took a rest, but we wanted to get at least to Przemysl [a town 90 km east of Rzeszow], we knew there were friends there, because people had already been fleeing the German-occupied territories, so they told us where the town council was, to go there.

I went there, the place was swarming with young people, and I presented the facts, how things were, in fact, my looks told everything! Half-withered, and they ask, ‘what name can you give us to prove that you are indeed with the communist youth.’ I remembered there was a liaison named Karol, so I say ‘Karol,’ ‘Well, he’s here with us!’ and that saved me, saved us all, they gave us a bus to go to Przemysl, and from there, by a train, to Lwow. It was late autumn 1939. We spent about a year in Lwow.

My mother and grandmother stayed in Rzeszow. Grandma was an old lady, how to take her on such a voyage? And my mother stayed, because otherwise she would have surely gone with us. In fact, did we know at all where we were going?! In Lwow I was joined by my brother [Mojzesz]. [He came from Bielsko Biala] because when the war broke out, the Germans announced that all young Jews, aged so and so, should report and told them to pack because they would go east to work there. And he packed everything he had into a suitcase and went east, in a normal car, not a freight one. In the meantime they were being beaten badly, he lost three teeth, and it was not the Germans who were beating them but Poles, civilians. I imagine they were young people, and they probably made a fuss because they didn’t know where they were going.

After they passed the border, they saw people working in the fields, in a forest; they guessed they were going to work. The train stopped, they got off, the Germans told them to pay 4 zlotys per piece of luggage, and peasants waited with wagons to take those suitcases. Then they lined them up in a row and the Germans started shooting, and when they started shooting, [my brother] ran away. And suddenly he found himself in one shoe on the Russian side, with nothing on himself, naked. Peasants allowed him to go into a stable, lie down. ‘After I woke up,’ he told me, ‘I got a second shoe, an odd one, and something to put on myself, some white shawl.’ He knew I was in Lwow; he wanted to get to Lwow. Only I don’t remember how he eventually found me.

[In Lwow] we lived in a former prison, the party found us a job and the place to stay. Me and two other friends got a job at the Aida factory: tubes, filters, and paper [a cigarette factory]. Every week we received an allowance of tubes, the kind of empty cigarettes, and there was a machine for stuffing them with tobacco. I didn’t need those tubes because we didn’t smoke, but I gave it to my brother who sold the stuff on the market. In fact, he had no job, so that was a kind of support. And the man he had worked for in Bielsko found himself in Lwow too and paid [my brother] five zlotys a week as a means of support, for nothing. He obviously had money.

Then we rented a room. The landlord [gave us] a single spring bed, but there was no mattress so we slept on the bare springs. The landlord lived in the same house, in a different part of it, and he knew we slept like that. He is surely dead by now, but if he’s alive, perhaps it pricks his conscience that he was so mean to us. Then my husband got sick, he had stomach ulcers, and people at my work helped secure a place for him in a sanatorium on Kurkowa Street, in Lwow, and he spent like two weeks there, but he was still sick, an ulcer doesn’t go away easily.

When he got back home, two uniformed men came and told us to pack our things. And what did we have? Nothing! A moment and we left, they took us to a freight car, didn’t tell us why. Did they know themselves? They didn’t – they had their orders, and that’s it. And so they took us to Kazakhstan, to Semipalatynsk [city in eastern Kazakhstan, 80 km from today’s border with Russia], we had no money, no clothes, we were hungry, like dogs, or worse. My husband had 100 rubles in his trouser pocket.

We had a friend in Semipalatynsk, a man we knew from Rzeszow, a communist too. His name was Motek, and we needed to find a place to stay, an apartment. He found one for us, we had to pay 20 rubles, and [my husband] must have obviously been robbed of the hundred. We were left penniless. [My husband] went to the other Poles to ask for a job, for something to do. They reacted in an ugly way, laughed at him, because they earned their living there by stealing. But he met three Czech guys somewhere who worked with horses, and they told him to come, that they would give him oats, and he came and had his pockets full of oats and we ate it.

The three Czechs who gave him the oats also fixed him a small job with a Kazakh man. They said [the Kazakh] would give him flour. [My husband] went to the man with some crewel and fixed his ‘shuba.’ A ‘shuba’ was a kind of sheepskin, [my husband] sat there, there was no proper table, only a low round one, you don’t sit on it; it’s for eating in a squatting position. Those Kazakhs had all gone to work and there came the Kazakh’s old wife, she was obviously preparing a dinner, and she had a knife, and the ram, smoked or raw, hung there, and she [was cutting it]. And [my husband] was afraid of the knife. And he ate his fill there. [The Kazakh] gave him a whole lot of flour, and I made my first potato dumplings then.

Of all of us, it was the hardest for our daughter Frania, who was born there in August [1941]. Shortly before that we got married; we went to an office to sign a document, there was no ceremony of any sort. We had to register officially, arrange the formalities. Frania went through nine pneumonias in a row. The Russians told me there was an establishment where I’d get food for her, and indeed, I regularly got a half-liter pot of some nourishment mixture, she was an infant, she couldn’t eat properly, so it was liquid, not pure milk but a pulp of some sort. And I had to leave her [with a babysitter] because we had no place of our own yet, and of all of us from that train had been billeted all together, and then I had to go to work, because that was the only way. In fact, we were young, you had to work; we had no means of support whatsoever.

And it was like that, when I worked, I received 600 grams of bread a day, and my daughter, my baby, whether it actually ate the bread or not, received 300 grams. And I gave that 300 grams to [the babysitter] in return for changing her clothes, feeding her the food I was receiving for [my daughter], and so on. Whether she fed her or not, I don’t know, but when I came, the [baby] would lay all buttoned up, red in the face, scorched, [the babysitter] didn’t change her, the baby just lay there, I can imagine how she cried, because it burns. [Then] I arranged for her to be admitted to a day care center and the Russian woman there told me, ‘For the burned skin, use “fasting butter”,’ this is oil. I applied the oil for the whole night, and it helped. How I managed to secure the oil, I don’t remember.

[Then I worked] in a tailor’s shop and everyday I carried the baby to the day care center. I’d wrap her in a cotton blanket using my husband’s belt, and when she heard me enter, heard me open the door, she’d start squealing – a little baby! She was just several months old. When I came to pick her up, it was winter time, they had no heating there, her hands were red, swollen, her legs chilblained, completely swollen, they sat at a round table, there were chairs to match, and how I brought her, so she lay there, in the same clothes, unchanged, nothing!

Then I started taking her with me to work, it was nearby, I’d put her on a table, unwrap, those hands were so swollen, cold, and you had to back home on foot, and there was heavy snow there, the snow banks were taller than a man’s height, you could only go where a path had been worn. Today I know it was a nice winter because there was no wind, if there was any, the snow banks stopped it. I had shoes back from Lwow, leather soles and canvas uppers, the three-fourths, laced-up kind of ones; they were all wet by the time I got back home. And at home there was no bed, no heating, nothing, no stove, we slept on the floor and covered ourselves with what we had brought with us. That’s how it was.

Meanwhile, my husband had been enlisted for the ‘trudarmya’ 10, the work battalions, to work with the horses. They slept on bunk beds, and there were lice all over the place. He got stomach ulcers there, and instead of feeding him the proper food, they simply fed him with what they had. In any case, my husband had a very strong will, none of my children were as strong-willed as he was, and he decided he’d go to town, to an official there in charge of labor. And he went there, on foot, and told the man about the conditions he worked in, about what they fed him, and showed him the medical certificate. The official picked up the phone and called the place where [my husband] worked. ‘If you can’t feed the man properly, then better send him home!’ he told them. And they released him. One day I look out of the window, and I see him marching with a bundle on his back. That way he got back. It could have been 1942, 1943.

Then my husband was hospitalized, and after he had been released, they enlisted him again, didn’t leave him in peace. Why did they enlist him? Because they were giving everyone Russian passports 11 and my husband didn’t want one, he insisted he wasn’t a Russian and wanted to live in Poland once the war ended. And those people that refused to become Russian nationals they often jailed, and him they enlisted [again], to work in a tailor’s shop, a military one. I cannot recall the name of the place. And it was good there for him, the manager told him there were unhappy people everywhere, because it was war, but in that place they were patriots. The young people would give their lives for Stalin, and for a ‘stakan’ – a stakan is a glass of vodka – and for something else, he mentioned three things, I don’t remember.

[Even in Lwow] my brother wanted to go back to Rzeszow. But he had no choice, had no work, and couldn’t go with us because they didn’t take him. They deported very many people, I don’t know what those people thought, generally people were afraid, and he fled somewhere to Bessarabia and wrote us a letter he had been enlisted [I don’t know to which army], and that we’d never see each other again, that was the last we heard from him. Perhaps he felt [he’d never return], that’s how it is when you’re going to the front. And that was it, we never heard from him again.

During the war me and my mother wrote each other, she begged me for some coffee, she obviously thought we had access to it here, so I sent her some, but it was chicory coffee, the ordinary one, and it was still very hard to get. I don’t know whether my mother was in the ghetto, or whatever happened to her, I only know what they told me after the war, that it could have august when they took them away, and my grandmother was shot on the street by the Germans, because she couldn’t walk. My mother wrote me that. That was 1943 or 1942 [Editor’s note: it was 1942]. My mother was later taken away, but I know nothing.

The war ended, and the Poles organized the repatriation, Wasilewska 12 arranged for those people to go back to Poland. And we went back. We were members of the Union of Polish Patriots 13. We arrived in Poland on 1st June 1946. We rode for two months on that train. We stayed in Szczecin!

My husband wanted to visit the place where he came from, and in 1946 he went to Rzeszow, we had a friend there, one Tomek Wisniewski, a communist from before the war, my [husband’s] friend from the same village. [My husband] went to him, and he tells him, ‘If you go there by yourself, you won’t come back! I’ll go with you.’ The realities were such that if a Jew had come back, he obviously had something to come back for, some property, and he’d get killed 14. And that guy [Wisniewski] went with him. My husband wanted to see the place, he was born there, went to school there, had his friends there. And he told me he couldn’t even recognize the place, he said, ‘The beaten tracks, the houses, here’s the house, with a thatched roof, and opposite a brick one.’ [No one survived of my husband’s family, only the adopted brother], Alman Intrater. My husband secured an official paper from a court, somewhere near Przemysl, confirming all those people were dead.

[Alman Intrater] went through all the camps here in Poland, and he was saved from a camp by some German nuns, he was already very weak, someone they called a ‘moslem’ [in the camp terminology, a ‘moslem’ was a prisoner on the verge of death, already so starved that he had virtually lost his will to survive], he could no longer eat anything, whatever he ate, passed through him in no time, so that was a pre-terminal stage, and then the war ended, and they took him to Sweden. They took him there because a Gestapo man had destroyed his eye with a whip, and they wanted to save his other eye, took him to a hospital, it didn’t work, he went blind. He told me later he would have died too because very many of those taken to Sweden pitched into food and died. You weren’t supposed to eat, and him they administered some medicinal charcoal in that hospital and he survived on that.

He had to be a very strong man, he was some kind of a military man in Poland before the war, but what kind, I don’t know. My husband visited him after the war, and saw him, but the other man couldn’t see him [because he was blind]. He married a Polish woman, lived with her in Sweden. And it turns out he died of a stroke, I don’t remember when. He survived everything else, but that – he didn’t.

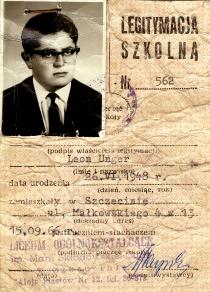

My husband had a job with the WPHO, a shoe-distribution enterprise that exists to this day. And I didn’t work. I had two children! In 1948 I gave birth to a son named Leon. He completed a musical school and is a pianist, and my daughter completed a business college.

[My children] went to the Public School no. 5, the communists’ children all went there. There was a period when religion started to be taught at schools [until 1961, religion classes were held at public schools], it was under Gomulka 15, I guess, and all the kids enrolled, communist or no communist, but [Leon] didn’t. The priest came, told him to stay, said God would bless him if he did, stroked his head, and [Leon] says there is no God at all. The priest got angry, grabbed him, opened the door and hurled him so the poor Leon landed under the opposite corridor wall, all bruised. But that wasn’t all, because after classes, in front of the school, the kids attacked Leon and started beating him. There’s a police station opposite and one of the policemen came up and he couldn’t tear the boy off because he sat on my son’s face and didn’t want to let go. When Leon came home, I called my neighbor, a doctor, and she told me to put him into bed and give him nothing to eat except cottage cheese. He got jaundice then.

My children knew from the very beginning [about their Jewish roots]. My son left Poland during the martial law 16 and went to America because he couldn’t get a job [here] because he was a Jew. And today he understands a lot because he lived among Jews in America. And they wanted to give him a job, only the rabbi told him to get circumcised. And he didn’t want to. Today he lives in Kiel [Germany] and remains a man at the crossroads, while my daughter wants to have nothing to do with all that; she’s married to a Pole.

My son didn’t want to get married, he had an ambition to have a high living standard, and today he’s old. My daughter has a daughter, Ania. She divorced her first husband and has married again. Ania’s father was called I., a Pole. I don’t know who he was or where he works – it’s been some years. Ania is 37. She worked as an English teacher in school, earned poorly, and eventually she made some arrangements and went to Sweden to work. She’s already been a year there, we’ll see! She had a husband, his name was K., but they got divorced, she has no children and cannot have any.

Me and my husband were party members uninterruptedly: before the war, during it, and afterwards. We were moved by 1968 17 like everyone else. Only we viewed it from a different angle: for us, those were mistakes committed by our own [the communists]. One generation has to sacrifice its life, its health, for things to change. We couldn’t leave [Poland] because by husband was seriously ill, he had already gone through one surgery, of the stomach, then of the gall bladder, there’s no hospital in Szczecin that he wouldn’t have been to, I had no one to go with. Me without a profession, the children, him being sick… That would have been like signing our own death sentence, as they say.

I am a member of the club [TSKZ] 18, but no activist, I just pay my fees. I couldn’t do anything even if I wanted to. In the past, I helped. Me and my husband had been in the club since the very beginning. There was a time when everyone had gone away and it looked like the club might be closed down. My husband had a talent, the talent of a social activist, and he organized everything, found a president and a caretaker. He died in 1993, but everybody still remembers him. We had never been to Israel, had no money. We have never been abroad, in fact.

I’m old today, 88, have trouble walking. But I want to live, don’t want to pass away yet. What else can I tell you? Everyone, if they have lived to the age of 88, have stories to tell, but is it important? It’s just life!

Glossary