Rosa Kolevska

Sofia

Bulgaria

Interviewer: Leontina Israel

Date of interview: December 2003

Rosa Kolevska lives in a quarter in Sofia close to one of the most beautiful parks of the city, Borisova Garden. She is a pensioner and lives alone in an attic apartment. One of her daughters lives with her family on the second floor of the same building. When I first went there, she came downstairs to meet me, as the entrance door was locked. This embarrassed me because she had to climb the stairs back up, which is quite tiresome for a woman of her age. At first sight Rosa Kolevska looks strict and cold, but in reality she is emotional and well disposed. Her room is full of family photos, mostly of her grandchildren. We carried out the interview on Saturdays and Sundays, when she had time to spare. During the week she has other obligations and occupations - she visits the Jewish organization and looks after her grandchildren.

I was born in 1929 in the city of Bourgas, where I used to live with my family till the age of three. My father's father Yako Cohen is from Aytos, but I don't know anything about his ancestors. Later they settled in Bourgas.

My grandmother Rosa Cohen, my father's mother, is from Bourgas. My parents and I used to live at her place after my birth. I remember her being very cheerful, kind and always joking. She was a brave woman! She coped with life on her own. My grandfather Yako Cohen had died very early leaving her a widow with six sons. She also had a daughter who died very young. She raised her children by herself. I don't know how she managed but she never complained. I suppose her elder sons worked and helped her.

My mother's kin is from Odrin. My grandfather on my mother's side, Meshulam Aroyo, comes from there. My maternal grandmother Evgenia Solomon Aroyo's parents were Solomon Behar and Mazaltov Behar. Solomon was born in 1860 and my great-grandmother in 1866. I know only that she was a little girl during the Ottoman yoke [see Ottoman Rule in Bulgaria] 1 and her family had already come to Bulgaria, but I have no idea when exactly.

My grandparents Evgenia and Meshulam were born in Sliven. I have wonderful memories of these grandparents of mine. I felt closer to my grandmother than to my mother. Unfortunately she passed away very early, in 1941. A photo album is the only thing I have from her and I still keep it, though it is already torn and the pictures have scattered, as a loving memory of her. She gave it to me as a present for my bat mitzvah. She was a very vivacious and courageous woman. Everybody loved her - my mother and me and all the other relatives. Besides she was a very intelligent woman; before her marriage she had worked as a teacher, which was a great merit in those times. Our family used to boast about this fact. You wouldn't have called her pretty, but she was a very nice and kind woman. A relative of ours, I cannot remember his name, used to come on a regular basis to ask for food. He was very poor, he wanted bread and yellow cheese and she never turned him down. Moreover she was never angry that such a small man would eat such an enormous amount of food. As a whole, my granny was more flexible than my mother and she got used to innovations more easily.

My grandfather Meshulam Aroyo was a very intelligent person too. He spoke several languages: in addition to Ladino and Bulgarian he also spoke French, Turkish and German. He did the correspondence of the local factory- owners. He cared a lot for his family as well as for the observation of the Jewish customs. My granny used to cook at home and I remember she used to prepare all kinds of cheese crackers and sweets traditional for every single Jewish holiday.

My grandpa had four brothers and one sister, all of them born in Sliven. His brother Isak was a trader. His wife's name was Bolisu. They had three children: Elia, Berta and Vitali. After the war [WWII] they left for Israel, where Isak remained till the end of his life. The second brother, Nissim, was also a trader. He lived in Plovdiv with his wife Rebecca and their children Berta, Marko and Eli. The third brother, Yakov, was also a trader and I remember that his second wife's name was Rashel. They had three children: Tsvi or Daniel, Sofi and Berta. Yakov died in Bulgaria, but I cannot remember the year. My grandfather's fourth brother, Iliya, was married to Mika. They had no children. They also lived in Israel. Their only sister Perla didn't work. Her father took care of her. She never got married.

I have a few memories of Bourgas, where we lived until I was three. At first we lived at my granny Rosa's place. I remember there was a large dining room there, in which a big lamp was on, but not an electrical one. My father had five brothers: Yeshua, Albert, Gaston, Leon and Yosif. They also lived in that house. Yeshua was married. I guess the daughters-in-law helped in keeping the household. They cleaned their own rooms first and then assisted their mother-in-law. I used to play with my oldest cousin Rosa; I used to call her Chechi, but I don't know why. My granny's house, in which we used to live, was actually rented. It seems that at that time people didn't really care so much about buying property. And not that they were poor. Only my uncle Leon did buy a house, which he sold when he left for Israel after the war [WWII]. I remember that later we lived at aunt Irina's place. She had a daughter, Lalka. The landlady loved my mother like her own child. Many years later, after I had graduated from university, I went to Bourgas and found the house. Aunt Irina was no longer alive, but I met with Lalka. This was in 1951. I don't know whether this house still exists today.

Yeshua used to sell flowers. His wife's name was Ester and she was from the town of Nova Zagora. They had two children: Yako and Rosa. Albert died young. His wife's name was also Ester, and she was from the city of Stara Zagora. They had two children: Lili, who died at the age of only six, and Rosa. The other brother, Leon, born in 1878, was a carter. His wife's name was Luna; she was from the town of Karnobat. Leon and Luna had two daughters: Rosa and Simha. My father's fifth brother Yosif's wife was called Mimi. She was from Plovdiv and I remember that she graduated from the French College 2. They also had two children: David and Rosa. Yosif was born in 1911 and died in 2002 in Israel, where he used to live. They also had a little sister who died very early. I don't know her name. All my father's brothers have a daughter named after their mother and my granny Rosa. I was also named after her. It was a family custom. My cousin Evgenia was named after my other granny, my mother's mother. Usually the child received the name of the grandfather or the grandmother after their death. In our family though my oldest cousin and I were both named after my granny Rosa when she was still alive because her sons respected her very much.

I don't remember a particularly Jewish neighborhood in Bourgas. It is true that a lot of Jews used to live on Bogoridi Street, some of whom I remember by name: tanti [aunt] Reina, uncle Mois; and there were several Assa families. Our house wasn't exactly on Bogoridi Street, but it was close. It was on a street parallel to Bogoridi Street. My father's brothers also rented lodgings in the center of Bourgas. My connection with Bourgas has never broken off. Although later we didn't live there any longer, I used to go there every summer, moreover I remember my mother taking me there as a little child in order to treat my rachitis.

I don't remember the synagogue of Bourgas, but I know there was one, as well as, most probably, a Jewish school.

In 1932 my parents and I moved to Sliven, because there was no work in Bourgas. There we first lived at my granny's place. There was a room made from bricks, built later than the rest of the house, and that was my parents' room. I remember a small and dark room, which later became our kitchen. There was also a little hall and another kitchen, albeit not a very nice one, with a dormer-window. That's how we lived before my sister Greta's birth. Later we rented lodgings at bai [an older fellow or uncle] Georgi's place. Later we rented another house at Bohor Navon's place. I remember his house was very close to my grandpa's place. One could enter it through a ladder from my parents' bedroom. That's how we went there, without going out into the street. We lived on the second floor of the house. The owner's two daughters and his son inhabited the first one. Bohor Navon had already passed away. There was a children's room, a bedroom, a dining-room, a large drawing-room, which we actually didn't use, as well as another room, which was very cold - most probably it was a northern one - and in which we used to store our food.

My mother, Berta Meshulam Aroyo, was born in Sliven in 1907. She studied in the Jewish school, which existed back then in Sliven, till the secondary school. Later she went to study in Rousse, in a Catholic college. She studied there for two years, and after that she returned to Sliven where she finished a Bulgarian school. She spoke French. She had learned it very quickly. Her father obliged her to write letters to him only in French, when she was a schoolgirl in Rousse. I have even seen such letters, written by mother in a very impressive handwriting. She spoke the language so brilliantly that almost 40 years later, in 1964, it happened so that some friends of ours from France visited us and they were really very impressed by her perfect French, which she hadn't spoken for many years. She was very clever, very studious. Sometimes she translated some articles for WIZO 3, but otherwise she wasn't an activist in such organizations. She was a good housewife and a good mother.

My father was quite a harsh man and my mother never had access to money. He used to buy everything, and the money he gave to her was always under control. Actually I didn't know my mother well as a child. I got to know her only when my father died in 1942. My mother had two brothers, Israel and Elia, and a sister, Matilda. Matilda had a twin brother who died very young. They were all born in Sliven. Israel was a trader - a carter. He had graduated from Robert College [a famous college in Istanbul]. His wife's name was Blanka. They had two children: Evgenia and Misho. Evgenia was named after our granny, my mother's mother, as well as after her father, and she resembled her in the courage she showed in everything. After the war [WWII] the family left for Israel. My uncle Israel died there in 1968.

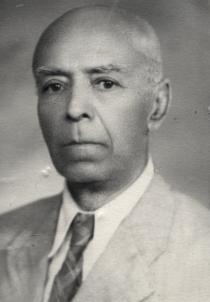

My father, David Yako Cohen, was born in Aytos in 1898. I don't know what kind of education he had. He started working at a very early age. He was a very strict man and I was afraid of him. He never beat me, but every time he raised his voice, I was dying of fear. Actually I didn't know him. Now I realize that at the time of his death he was in fact quite a young man - only 44 years old. His friends were mostly Bulgarians: a watchmaker, a factory-owner, and a furniture manufacturer. My father was a very worldly person. He wasn't religious, but he insisted on all of us being at home for dinner. He never stayed in the tavern like most Bulgarians used to do. There were several Bulgarian families, with whom we kept very close friendly relations. We even taught them several Spanish words.

My father had a shop in Sliven, which he actually rented. We never owned anything. He used to sell maize and flour. He was a representative of the Big Bulgarian Mills [co-operation]. We were neither poor, nor rich. My father didn't work alone in that shop. I remember, for example, that there was a Turk, a carter, who used to help him. There were other representatives of the Bulgarian Mills in the town too; he wasn't the only one. My father was the soul of all the Jewish holidays we celebrated at home. He wasn't religious and we didn't even speak Ladino at home. Though Ladino was spoken both in my mother's and my father's families, we used to speak Bulgarian at home, and moreover, it was proper Bulgarian. For example, we never said 'chushmya', as some people in Sliven pronounce it, but we pronounced it correctly as 'cheshma'. [Editor's note: 'cheshma' means fountain.]

Before my parents got married, my mother's relatives had introduced her to some other 'candidates'. She was very beautiful! People used to call her 'Pretty Berta'. They arranged a meeting for her with a Romanian, but he wanted a very big dowry, which her parents couldn't provide. Later they also arranged other meetings. Finally she was introduced to my father. That's how they got married, without having a romantic relationship, but they both fell for each other instantly. They had a religious marriage, as was common for all Jews at that time.

I remember we had a gas lamp while we lived in Bourgas. Later, in Sliven, we also had a gas lamp, as the winters there were severe: strong winds blew and there were a lot of power cuts. Naturally we had running water as well. Even our toilet was within the house. There were both a toilet and a bathroom in the house, but it was still very unpleasant to go downstairs in wintertime. The bathroom was rather primitive - with a vessel, where the water was warmed up with firewood - but it looked like a bathroom anyway. At my grandfather's place there was a separate building, in which the dishes were washed and the laundry was washed in ashy water. Usually water was left to be warmed up by the sun, though this could also be done by means of firewood. There was a well in the yard. There was an underground river passing through the yard and unfortunately my uncle had built his house right over it. Even now this house is cold and wet. When I was a child I used to hear the river's ripple. Before the well was cemented they used to cool watermelons in there. They had always had cold water.

We had a yard with a lot of fruit-trees. We had quinces, several sorts of plums, apricots, apples and pears. Now there are fig trees also, but I cannot recall whether they were there when I was a child. In the neighboring yard there was an apricot-tree, whose branches rose even above the house. They used to tie swings for us there, so that we could seesaw. We also had vine with delicious grapes. My granny used to take care of the flowers - roses, gillyflower and many other kinds.

Sliven was an industrial town, which had an intensive cultural life. There was a theater and an opera house. There was a 'chitalishte' 4, 'Zora' [dawn], with quite a well-stocked library, several bookshops, banks and pharmacies. The streets were clean and tidy; the buildings had a nice architecture. Sliven was famous for its socks and textile factories, etc. The monument of Dobri Zhelyazkov, the first factory-owner was there. Sliven was a cultural center: Elisaveta Bagriana [Bulgarian poet, born in Sofia, studied in Sliven], Dobri Chintulov [Bulgarian poet, born in Sliven] and others lived there. I don't know the number of its population neither then, nor now.

I don't know how many Jews used to live there at that time, but I remember it was quite a large community. I don't recall a particularly Jewish quarter. I remember Dr. Israelov, a physician, the Alkala family, quite well off people, Mr. Kemalov, who had a bank and others. All Jews in the town were honest, decent and hard-working people. There were tinsmiths, merchants, doctors, dentists and bankers and there was also one shoemaker. There were several workers as well. We didn't purchase goods only from Jews, yet my granny, for instance, regularly bought textiles from a trader called Yomtov Geron. My granny told me that at the beginning, when she went for the first time to buy fabrics from him, she spoke in Bulgarian and everybody there spoke in Ladino. He had several Bulgarian girl-assistants, who had learned Ladino from him. And when my granny asked for the cloth in Bulgarian, he said in Ladino to his assistants to give her from the lower quality cloth, as she wasn't a regular customer. This was followed by such a great scandal that in the end the trader wondered where to hide.

My uncle Yako had also a textile shop and his assistant was also a Bulgarian, who also spoke Ladino. Some Jews in Sliven had small factories and workshops. There was a family, which had a blanket factory. Actually it was a workshop. There were also corn-chandlers, dairymen, teachers and tailors among the Jews. There was also a carter. He was one of the very few Jews who drank. There were also two Jews whom I found very disgusting. They wore awful clothes, they were unshaved, and they drank and spoke in an ugly manner. Nevertheless, in accordance with the Jewish religion our community supported them, as they had no money, but they usually spent the money in the tavern and they did absolutely nothing work-wise. There were also other poor Jews yet they worked in order to earn their living.

I remember the synagogue in Sliven unlike the one in Bourgas. Women usually sat upstairs together with the children, though they often chased us out, as we used to be very noisy. The yard was very large and we used to play a lot in there! A sukkah was regularly built there on Sukkot. There was a chazzan, but there was no rabbi. From time to time a thin, red-haired and poorly dressed man went about the streets. He was called shammash and his job was to invite people to go to the synagogue and to explain when the candles should be lit. The hakham was an extremely intelligent man, who had two wonderful sons and a wife, worthy of being the hakham's wife. Then another hakham came, who was quite unpleasant and his wife was uneducated. They subsisted on selling peach and apricot pits, which they soaked so that they wouldn't taste bitter. Frankly speaking they were a real disgrace for the Jewish clergy [community representatives]. The Jewish weddings were performed in the synagogue but not all of them. There were also people who performed the ritual at their homes in accordance with the Jewish traditions. I remember my uncle Israel's wedding, which was held at their home and there was something like a tent set up there.

There was a Jewish chitalishte in Sliven as well. My first memory from a visit to that community center is from 1939, when we were gathered for a talk about the destiny of Jews and the policy of Germany. It was a very nice place - we celebrated holidays there and organized performances. Once, for example, we staged how Rachel was married, that is how Eliezer went to take her as a wife for Isaac; I have already forgotten the name. Anyway, I was playing the bride. I burnt with shame then! Since I had to look like a bride I had put on a nightdress of my mother, but we hadn't taken into consideration that it was transparent. So, everybody laughed at me. We had to think of some kind of a lining ... We had various kinds of performances. We didn't have the intention of creating true art, but it was amusing indeed. Our life was nice then! There was a Maccabi 5 organization in Sliven as well. We were given lessons in singing and dancing. There was also Hashomer Hatzair 6, but I don't recall anything of it, as I was too young at that time.

We observed the kashrut at home, at least until the occupation, when it became impossible to choose what to eat because of the lack of food. I even remember that during the war [WWII], when I was forced to taste pork for the first time in my life, I became sick. It stank horribly but there was nothing else to eat. I gradually got used to it. We got supplies of kosher meat from the shops, where the chazzan used to go about and put a seal on some of the meat. We didn't have a shochet. The hakham slaughtered the hens and we brought them to him in order for him to examine the meat. If it looked good, we ate it, if it didn't we threw it away. We didn't have separate dishes for meat and dairy products. There were several families who observed the kashrut strictly. They even called Bulgarians to light the lamps at Sabbath.

Most of the Jewish holidays we celebrated at home, but sometimes we went to the synagogue. My grandpa went there. I remember him wearing a tallit, Tannakh but I don't recall him wearing a kippah. I also remember our rabbi wearing a big white hat with a pompon. As I said, my father was a worldly person; he wasn't religious. But that doesn't mean that we didn't celebrate the holidays. I don't remember us celebrating Sabbath, nor do I remember lighting candles. But I have memories of other holidays.

My favorite holiday was Purim. We made mavlach in various forms - scissors, hearts, etc. 'The tongue of Haman' was also baked on Purim. It was a sweetmeat like a fat biscuit in an oblong form, and at one of its ends there was an egg resembling the man's throat. 'Haman's hair' was also made - kadaif [a sweetmeat made of dry pastry threads, baked with butter and walnuts and soaked in syrup], as well as 'Haman's ears'. These kinds of 'Haman's ears' are not prepared everywhere. I have seen them made in the form of triangles, while in Sliven, Bourgas and probably in Yambol also, and in Stara Zagora some kinds of honeycombs were prepared that were pinched and resembled the shell of an ear. Once a competition was organized in the Jewish community center for best costume. Mine was made of stretchable paper. I was disguised as a snowdrop and I was convinced that I would win that competition. To my greatest disappointment some other girl with a Hungarian costume was awarded the prize. Actually the most original costumes belonged to Venis and Zhula, but they were the contest organizer's daughters and it wasn't proper for them to win.

We celebrated Rosh Hashanah, but also the New Year on 1st January. On Christmas came koledari [traditional Bulgarian Christmas custom, in which men called 'koledari' go about people's houses and sing songs as a good health wish] and sang songs to the maidens. We did not separate from the Bulgarians. To the right of my granny's house a Bulgarian family used to live - the family of baba [granny] Tsanka, who had a son and a daughter. We were very close to them. They had a fulling-mill. We used to exchange tidbits on every holiday with them - on Easter they brought us red-painted eggs [widespread Easter custom] and we gave them brown ones on Pesach.

For Pesach we always had matzah, which wasn't like the one that exists today but quite a bit rougher. Besides our mothers made pitas. We also made tishpishti [a Jewish sweetmeat with walnuts] and burmoelos 7. My mother didn't have separate dishes but before every holiday they were all boiled in ashy water in order to be cleaned.

For Fruitas 8, Tu bi-Shevat, we made special satin bags and filled them with fruits. There were carobs, peanuts, and almonds... All of us prepared them.

I don't recall a special custom for Chanukkah. On Yom Kippur we tried to do taanit [fast], but it almost never worked out, as it was also forbidden to drink water. The Bulgarian school always excused us when we celebrated the Jewish holidays, at which we were even allowed to stay at home. We didn't have any limitations. Sometimes, at the beginning of the lesson, I used to say a prayer, which none of the other children knew, only I knew it. This was in the Bulgarian school where we studied French. We knew Christian prayers in French, which I also said sometimes as I had learned them. I didn't have the feeling of betraying my own religion because we weren't religious at all.

My granny used to prepare a sweetmeat made of almonds with a very little quantity of flour and eggs. Those were cone-shaped pieces, with yolk spread on them, and an almond on top of each one. I ate such sweets when I was in Israel. We made kezadas - of borekas' pastry, round, we put fresh cheese and eggs in it, and then we browned it. It looked very beautiful. My mother and my granny used to prepare all kinds of delicacies. They took care of the household and looked after my sister and me. I didn't go to a kindergarten. There was one for the workers' children, as they didn't have the opportunity to stay at home the whole day. It was a common practice to have a maid at home. I have most wonderful memories of ours; we loved each other very much. I remember Radka, then Kina... At home they learned how to cook, to keep a household and clean. We took care of them; we bought them clothes and shoes. They were from villages near Sliven. We never treated them haughtily. Our relations were completely natural.

I had a happy and peaceful childhood. We played all kinds of games - 'kralio [king] - portalio [gate]', hide-and-seek, tag, 'handkerchief', 'ring', 'telephone' and many others. There was a large space in front of my granny's house and we used to play there, not in the street. I had a friend from the neighboring house. Her name was Katya and she wasn't Jewish. In the afternoon every child used to go out with a slice of bread with jam spread over it. We used to prepare everything at home. We made rechel [Turkish; boiled and condensed juice made of grape, sugar-cane, sugar-beat or pears, sometimes with pieces of pumpkin or fruits added] butter-dishes - strung up walnuts, which were several times dipped into a farina gruel, sugar and must. This resulted in 'sausages' that we used to cut. My granny also made something of rice, which she left in water in order to soften and then she prepared it.

My sister Greta was born in Sliven on 17th September 1933. I was very jealous of her. She was rather spoiled, because she was a very beautiful child with huge eyes, and people paid attention only to her. Once, I don't know how it happened, I was hit by a cart. Fortunately I wasn't wounded at all, but everyone got pretty scared. I remember I was lying on the ground and people were bustling around me, when I suddenly said: 'Come on, come on, I know you aren't worried that much about me!' It is the baby only that you love!' Later, when we grew up, my sister in return felt somehow neglected. There was probably nothing like that. My grandpa, for example, gave open preference to the youngest person in the family. He always loved the last-born child, and ignored all the rest.

I started my education in the Jewish school in Sliven. It was situated in a large building. I don't remember what there was on the first floor, but we were on the second floor - one teacher's room and two very big classrooms. We had two teachers - one in Ivrit and one in all the other subjects. We were four classes altogether, two in each one of the classrooms, but the teachers managed to teach us. At the end of the year inspectors came from the Ministry of Education in order to examine us, and we always got excellent marks. My mother had also studied in that school; she had learned Ivrit there. At that time school was until the 7th grade. Mrs. Ester was our teacher-of-everything and she was an amazing teacher! The other teacher, poor one, seemed to be quite ill and always nervous. She also taught us the Torah, songs, etc. which later helped me to freshen up my Ivrit and learn new things. I still recall these songs. My sister also studied in this school.

Our preparation in the Jewish school was so good that when we entered secondary school all of us were excellent students. I remember my literature teacher from this period - she was a good teacher, and there was another one, the geography teacher, whom we disliked. Then there was a young history teacher, with whom all schoolgirls were in love. In our singing classes we were taught to sing Rhodope Mountain songs; we also had a choir. The scariest teacher was the one in maths. Once during a term test my cousin asked me to give her a hint and the teacher saw me. In order to punish me he ordered me out of the classroom and gave me a poor mark. I have never felt so ashamed in my entire life! Although my uncle was a friend of his and asked him to test me, he didn't do it and gave me a four [that is C] at the end of the year. I suffered a lot then.

My favorite school subjects were Bulgarian, history and, later, in high school chemistry, perhaps because of the teacher. I also liked my history teacher; not everybody liked her. She was cold, yet very logical in terms of her teaching method. Everything was in its place; she wasn't emotional, yet she spoke convincingly. Later we had a teacher in drawing, whom all of my classmates used to adore and I solely disliked, because she used to speak like an actress, with a kind of pathos that didn't impress me. I didn't like maths and I didn't understand physics. I loved French. Initially my mother found me a teacher, who actually didn't teach me anything. Later I continued with a teacher, who had graduated in France. She taught me the basics, but I still couldn't speak the language. Many years after that, maybe in 1964 it happened so that we were in Zakopane, Poland, on some kind of holiday on an exchange basis, and there were Italians, Spaniards and French. With the latter I wanted to speak in French, yet it turned out that I couldn't. Then I started studying the language very hard with a teacher, whose mother was French. Well, I still don't know it perfectly, but I manage. I speak with few mistakes and read criminal novels.

My father died when I was 13. At that time my mother didn't have any education and she had nowhere to work. My uncles used to provide for her. It's not an easy thing to live at someone else's expense though and we did our best to save. All my friends got 'semanada' - pocket-money, which their parents used to give them per week. It wasn't that much, yet it was money anyway! I never got anything like that, not even when my father was alive, let alone after his death. I remember it was the big boom of Deanna Durbin [Hollywood actress and singer]. These were films with songs, dances, girls' favorite ones. Once after we had watched the film in the theater, my friends wanted to see it again. I had no money and one of the girls offered to pay for my ticket. And so it happened. Yet, their family wasn't like ours - they used to tell each other everything and she shared with her parents that she had bought my ticket. They in return told the widow, my mother. The ticket was 50 stotinki. I have no idea whether that was a big amount then or a small one, but I remember when everyone gathered around me scolding me. And what could I possibly do?! That film was so sweet, that one could watch it three or four times. Yet, it wasn't a custom for a fatherless girl to watch such films even once, and I, outrageously enough, had seen it twice. It was such a shame! Generally my relatives used to watch a lot over me. When my father was still alive, he sometimes used to come and get me when I was playing games in the street in broad daylight. When he died, my uncles kept watching over me like dragons.

Upon the beginning of the war we gradually stopped lessons at school and the school buildings were occupied for other purposes. As a result of this I suffered a lot of gaps in my high school education. We were given diplomas without actually deserving them, but what is to be done! It was no one's fault - neither the teachers' nor the students'! Practically we didn't have school lessons on a regular basis. We just went there and read. The 'nazified' brains of the teachers gave birth to sentences like: 'Look, the little Jew speaks Bulgarian better than you!', otherwise they didn't maltreat us. I've heard offensive words like 'chifuti' 9 or expressions like 'it's a Jewish affair', without anyone having the slightest idea what exactly it meant. Rumors were spread among Bulgarians that at Easter time Jews used to put a Christian child into a cask pricked all over with nails and rolled it down a slope, in order to supply themselves with blood for drinking [blood libel accusation]. Although such beliefs existed among Bulgarians, they were not widely spread.

The situation got worse when the Germans came and all 'Branniks' 10 and 'Legionaries' [see Bulgarian Legions] 11 emerged. Otherwise I had all kinds of friends - Bulgarians, Jews, an Armenian and a Turkish girl. Initially there wasn't any tension among us and the separation was somehow artificially created. During the war [WWII] there were plenty of hints and writings on the walls that provoked intolerance. When the laws against us started, an evening hour was introduced. Also, a quota for enrollment of Jewish students in high school was accepted - for example, three students were admitted to high school and the rest had to enroll in the technical school, and so on. Some of the Branniks even went beyond the limit and while watching the beautiful Jewish girls, used to say: 'I hate Jews but I love Jewish girls', which was quite an ugly thing to say. In accordance with the Law for the Protection of the Nation 12 my father was deprived of the right to own a shop, although he continued to work in it after the shop was transferred to another person. The same happened with my uncles, who used to have an electricity materials shop. During the war [WWII] they transferred it to one of their workers and after the war they didn't have problems regaining it. That is true: Jews weren't allowed to work in order to earn their living.

All my paternal and maternal uncles were in labor camps during the war, after 1942. My father died in 1942, before they were sent to camps. He was extremely sensitive about the attitude towards Jews. Wearing the yellow star was painful for him. [In Bulgaria yellow stars were like buttons, with two holes sewn on the lapel.] He was a worldly person, most of his friends were Bulgarian, and he couldn't take the humiliation.

I remember an interesting incident regarding these yellow stars. In order to travel to another town, we needed special permission. However, every summer I was used to travel to Bourgas, so I took off the badge, bought a ticket and went to visit my cousins there. Suddenly a higher police officer - a commandant or something like that in Sliven - came across me in the center of the town and recognized me. Anyway, I decided that I would lie to him and started inventing a story that I had a cousin in Sliven, who resembled me very much and that he was mistaking me for her. How could I possibly think that I would get away lying to him, even as a joke? It is true that my Bourgas cousin's name is Rosa Cohen, just like mine, but anyway... Then he took me to the police station, questioned me and I confessed. In the morning my maternal uncle came to take me home. This was one of the few adventures in my life. Most probably I did it not out of bravery, but out of stupidity.

During the war [WWII] I wasn't that young anymore, already about fifteen, and still I was very naive. As though I didn't realize what exactly was going on. Whether it was my mother who kept me aloof of everything, I don't know. I remember some incidents. There was a sweet shop in Sliven, whose owner was an Albanian. We loved to go there and have something sweet. During the war a sign appeared on its front door saying 'Entry forbidden for dogs and Jews!' My parents were well informed of what was happening on the front. Radio sets were forbidden for us, Jews, and they were jammed. Somehow my grandfather switched ours on and used to listen to it quite often, frequently exclaiming aloud, 'There is no logic!'

We knew about the existence of anti-fascist organizations in Bulgaria during the war, moreover many of the members of these organizations served their sentences in the Sliven prison, including Jews. I remember that even in the Jewish community center they explained to us what was happening to the Jews in other countries, but this information seemed distant to me. On 9th September [1944] 13 I was in Bourgas. I was working temporarily in a socks factory. People went out in the streets for a manifestation and all of them had put red ribbons on their clothes. I suppose that this day was more moving in Sliven, as the partisans had come down from the mountains and had liberated the political prisoners.

After I graduated from high school, I wanted to study chemistry at university; this was already after 9th September 1944. It was very interesting to me, but unfortunately it happened so that in the same summer I had to study for the exam, I went on a brigade 14 and something bit me there. My leg was swelling up, I had a temperature and that fever lasted for days. Finally they opened my wound, as there weren't any antiseptic medicines at that time. Only when I became a student I used to go to the Jewish hospital and the doctors there used to put some kind of powder in my wound, in order to heal it. Thus my presentation at the exam failed and I got 3,50 [lower than a good mark]. And how much I cried then! I didn't want to become a teacher, but gradually I began to love my job.

When I was accepted to study Russian philology, I came to live in Sofia and found a lodging. My mother stayed in Sliven. She finished accountant courses and started working as an accountant. Later she worked as a chairwoman of a co-operative, which dealt with the collection of waste textiles from the plants and recycled them into children clothes, pyjamas and toys. Mostly Jews worked there. My mother often traveled on business trips around the factories in order to buy textiles almost dirt-cheap. The first children clothes of my older daughter were just like that. I lived in a lodging at a Jewish family's place in Sofia.

I had a very difficult studentship. I didn't receive a grant because my mother had a certain income, although low. Anyway, I didn't tell her that I had no money. My older maternal uncle, who went to Israel and left some money to me, provided the only income I had. I allocated it and when I included the rent as well, it turned out that what was left for my daily portion of food was just enough for soup. I didn't have enough money to eat in the university canteen. Every day I visited the 'Bunch' restaurant and ordered soup there; the bread was for free. The waiter always asked me if I would like anything else, but I always sent him away.

The second year was much better and I used to live in a different way because I was already given a grant from the university. I remember once I broke my glasses and I had to sell my coupons for the week in order to buy myself a new pair of glasses. No one of the present-day students could ever imagine what it was like back then. Anyway, I didn't felt unhappy or unsatisfied; on the contrary, I was cheerful. It wasn't pleasant that I was constantly hungry, but it wasn't that hard. Clothes, shoes - everything I used to wear - were altered into new ones.

I graduated from university in 1951. I was immediately offered an appointment in Sofia as a 'model teacher', but I didn't have enough confidence. I wanted to go to Sliven, but another girl was sent there. Then I was appointed a teacher in Bourgas, at the Teacher's University, where I had to instruct future teachers. It was a hard job to do! Some of my students were older than me; I was only 22, and I had students aged 28 and 30.

I was already married at the time. I met my husband at university, when I was still a student. At the time I was in Bourgas, my husband worked in the former Soviet Union. I stayed in Bourgas until my older daughter was born, and then I moved to Sliven in order to wait for my husband's return. I had favorite students among the students. I remember one - Hristo was his name. He was a nice guy, blond, with light eyes; I've always liked fair people. I didn't want the others to suspect my attraction to him; therefore I always lessened his marks.

The fact that my husband was of different faith has never bothered me. The times were such that we didn't pay much attention to these things. As a student I had one or two Jewish 'candidates'. The first one was older than I was and my relatives had introduced me to him. He was some very distant relative of mine. There was another one from Plovdiv, of whom I remember only that his name was Yosif. He wooed me, used to take me to theater performances, but I was in love with a Serb. This, of course, happened before I got married. Once we met the Serb on our way to the theater. I put off Yosif, hoping that the Serb would like me. Nothing like that happened. I had another worshipper from Bourgas. I was still a student and he was five years older than I was. I must have felt flattered that he wooed me. We used to write letters to each other, but frankly speaking I didn't have any feelings for him whatsoever. Once he tried to kiss me, which disgusted me and I washed myself with water and something else, I cannot remember what. It was so repulsive! I was still a young girl after all! I don't know how I fell in love with my future husband, but it happened so. I didn't have any love affairs, only him.

My mother didn't oppose to the fact that my husband wasn't Jewish. The first time I took him to Sliven in order to introduce him to my family, my aunt's father had died and I was worried that it wasn't a proper moment, but she told me to bring him there. He even slept at her place, as our house was a very small one - we had just one small room and a small kitchen. Everybody liked him a lot and they continued to like him, until the divorce that is. However, my granny wasn't very pleased. Perhaps my grandpa shared her feelings, but he was a tactful person and he would have never said anything that might have hurt me. My husband was called Vassil Lambrev Kolevski. He was born in the village of Yavorovo on 6th March 1925. He graduated in Russian philology just like me. He is a professor; he used to be rector at VITIZ [Higher Institute of Theater and Film Arts, now NATFIZ, National Academy of Theater and Film Arts], and he is also a writer. He wrote five or six books, most of them on communist topics. He has two sisters, Penka and Vesselina, and a brother, Iliya.

My sister Greta finished her studies of Russian philology just like me. First she wanted to study biology, but later she took up philology. She was allocated to work in the village of Belovo. A cousin of ours introduced her to her future husband, and it seemed as though she married somehow deliberately, as she didn't want to stay in the province. Her marriage wasn't a happy one because they weren't a match. I still keep thinking that if she had been with somebody else and he had been with somebody else, both would have been happier. They have one son - Anri, born in 1959.

When my older daughter Natasha was born in 1953, I was 24 years old and I think I wasn't mature enough for motherhood. My husband was still in Moscow. Perhaps I've made a mistake being a young mother. In 1960, when our younger daughter Bisserka was born, I used to call her 'the little gift'. I was already longing to be a mother. Now it seems that I get along better with my older daughter, but I've always treated them in one and the same way. They are quite different from one another, they belong to different generations, but they love and understand each other. My older daughter was born in Sliven, and the younger one in Sofia.

Upon my husband's return from Moscow, we moved to Sofia and I began work as a teacher in the Ballet School. At that time it was a part of the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union House on Stamboliiski Street. We were on the 7th floor. As a whole, it wasn't good enough for a school. I remember several students, who were my favorites there. There was one, Katya, who was like a daughter to me. She didn't come from a good family, but she was an excellent student. And there was a boy, Petyo, who was also one of my favorites.

My daughters first studied in 56th School; later the older one finished 119th High School and the younger one 'Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin' Russian High School. Natasha studied for three years literature at Sofia University, but she wasn't happy with that. She wanted to study in VITIZ. Her father used to be its rector for while, but he wasn't among the favorites there. Nevertheless she passed the exams because the contest was anonymous. She finished Drama Critique with excellent marks. In my opinion she made great progress during the years when she studied literature. Before that she wasn't the best student. My older daughter worked for a while in a theater repertoire center at the Actor's Union, together with theater directors, translators and writers. Finally she was laid off because of staff reduction. She was unemployed for six years, yet she never stopped writing articles on theater. Currently she works in the Bulgarian Army Theater.

My younger daughter surprisingly enough said that she wanted to become a puppeteer. She had a speech impediment - she couldn't pronounce 'l' properly and she had to put in a lot of effort in order to overcome this deficiency. Then she applied for directing and she was accepted. She made a good presentation. I don't know why, but maybe in the third course her professor told her that she didn't have enough qualities to become a director and suggested to my daughter to change her specialty. And so, Bisserka graduated as a puppeteer. Upon her graduation she went to work in the Stara Zagora Theater. There she had an opportunity to pass the director's exam, and finally she did become a director. Now she works as such.

Although they are from a mixed marriage, my children feel Jewish. I acquainted them with the traditions as best as I could. My mother was offered retirement when she was only 50. I considered that it would be ugly to leave her alone in Sliven. Therefore I invited her to come and stay at our place in Sofia. Maybe it was a mistake on my side. My mother was the soul of the house. The children, my husband and I loved her very much. But practically she didn't have any self-dependence. Maybe she would have been much happier if she had remained in Sliven. As long as my mother was alive, our cuisine was a Jewish one. We didn't celebrate Sabbath, we didn't observe the kashrut. On Pesach we prepared 'Haman's ears' and bought matzah. We tried to follow the traditions. In Sofia my mother didn't work; she took care of the household, yet she was young and healthy and she could have continued working.

I got divorced in 1979. I retired in 1984. I didn't want to, but that's what the new director of my school suggested that I did. Then I started working as a lecturer in various higher institutes and that lasted until 1990. It was very nice. Students cannot be compared to pupils. They have a deeper interest and sometimes they even made me stay in the breaks in order to talk with me on different interesting topics. This is quite unlikely to happen among pupils. Moreover the 1980s were extremely exciting - the changes in Russia, Gorbachev 15, the books that had been banned or had been locked away in drawers, were finally published. Although I was divorced, I had enough money because I worked a lot.

The changes in 1989 [see 10th November 1989] 16, the fall of communism in Bulgaria, affected me financially. All prices rose and it became very difficult to get supplies of any kind of products. The situation was just like the one right before 9th September 1944.

I wanted very much to leave for Israel. I went there for the first time in 1979 together with my younger daughter Bisserka. My mother and my sister had already been there before. I liked it very much and I was very well accepted. I have many relatives there - my mother's brother and sister, my father's siblings and a lot of former classmates. During my first visit to Israel all Sliven-born fellow citizens gathered for a celebration. My strongest impressions from Israel were from that very first visit. My relatives invited me to stay there, but I couldn't. I wasn't ready; my divorce wasn't yet finalized. I wasn't mature enough for such a step. Later I did want to do so a lot, but I didn't dare go there all by myself. It was already too late! I am deeply sorry! I like life in Israel very much! Of course, there are unpleasant things there too, but I like even only inhaling the air there.

In 1964 my ex-husband and I bought the apartment inhabited now by my younger daughter and situated on the second floor of the same building, in which I live. Back then this area used to be very nice! Although it is still a calm residential quarter, at that time there were only little houses with lovely yards. It was very beautiful indeed! My husband used to take care of the garden, which we had in the backyard of the house. He used to grow tomatoes, raspberries, strawberries, beans and even potatoes. It was a nice period of my life! The children grew up in a calm atmosphere; they used to play in the yard. Later that ugly house was built next to ours, which finally hid the sun from the first floors of our living estate. In 1996 I went to Israel and upon my return the children had already prepared the attic, where they suggested me to move to. Before that I used to have a lodger from South Korea in there and that's how I managed to support the apartment, but she had already moved out. Moreover Bisserka was expecting her second child, Stefan, so I had to move out. I have already lived here [in the attic] for seven years. The only thing I dislike about it is that I have to climb so many stairs. In 2000 I had several heavy operations on my legs and they are hurting now. I even thought that I wouldn't be able to walk again, but I'm fine now.

My older daughter Natasha has a daughter, Bozhana, born in 1977, and a son, Valentin born in 1982, while Bisserka has a daughter, Ana-Maria, born in 1990 and a son, Stefan, born in 1996. They are all very smart kids. My oldest granddaughter lives abroad. The youngest grandchild, Stefcho [diminutive for Stefan] studies in the Jewish school. And, I have raised Ana-Maria almost by myself.

I visit the 'Health' club at the Jewish community center, as well as the 'Ladino' club and the 'Golden Age' club. Last year I went to the 'Health' club as well, but I couldn't visit it on a regular basis as my granddaughter often fell sick and I was looking after her. I don't go for lunch to the Jewish community center like many of the elderly people do, as I pick up Stefan from school. All in all, I have both obligations and amusements.

During the summer I hesitated a lot whether to go on an excursion to Bankya [a resort near Sofia], which was organized for us, but I finally decided against it. I'm an elderly person, I have certain habits, and I would be disturbed if they were to be broken. I know it would have been nice, but that was my decision. I cannot say that I have many friends in the Jewish community center -I rather have acquaintances, a cousin and a colleague, Reni Lidji, but they have been there for a very long time already, and it feels like there is a certain distance. But perhaps I'm only imaging this. Nevertheless, I like going there. I like traveling abroad also, and especially so to Israel. I have a cousin in Spain and I visited him there. It was wonderful! Before we got divorced my husband and I traveled to France, and after that I went there by myself.

Currently my sister lives in Israel, in Tel Aviv. After my mother's death Anri left for Israel and remained there. It seemed as though his decision to settle there was spontaneous and yet I think that he had made that decision before he left. Later my sister and her husband, who passed away shortly after as a result of a heart attack, also left. My sister didn't live very well in the beginning because she cherished the illusion that the state would take care of all her necessities, while in reality the social support she got was rather insufficient. Currently both she and my nephew are quite well off. He lives in Ramat Aviv and his mother is looking after his children.

Glossary

1 Ottoman Rule in Bulgaria: The territory of today's Bulgaria and most of South Eastern Europe was an integral part of the Ottoman Empire for about five hundred years, from the 14th century until 1878. During the 1877-78 Russian-Turkish War the Russians occupied the Bulgarian lands and brought about the independent Bulgarian state, which however left many Bulgarians outside its boundaries, mostly in areas still under Ottoman rule. The autonomous Ottoman province of Eastern Rumelia united with Bulgaria in 1885, and Bulgaria gained a small part of Macedonia (Pirin Macedonia) in the Balkan Wars (1912-13). However complete Bulgarian national unity was never achieved as many of the Bulgarians remained within the neighboring countries, such as in Greece (Aegean Thrace and Makedonia), Serbia (Macedonia and Eastern Serbia) and Romania (Dobrudzha).

2 French College: An elite Catholic college teaching French language and culture and subsidized by the French Carmelites. It was closed in 1944.

3 WIZO: Women's International Zionist Organization; a hundred year old organization with humanitarian purposes aiming at supporting Jewish women all over the world in the field of education, economics, science and culture. Currently the chairwoman of WIZO in Bulgaria is Ms. Alice Levi.

4 Chitalishte: literally 'a place to read'; a community and an institution for public enlightenment carrying a supply of books, holding discussions and lectures, performances etc. The first such organizations were set up during the period of the Bulgarian National Revival [18th-19th centuries] and were gradually transformed into cultural centers in Bulgaria. Unlike in the 1930s, when the chitalishte network could maintain its activities for the most part through its own income, today, as during the communist regime, they are mainly supported by the state. There are over 3,000 chitalishtes in Bulgaria today, although they have become less popular.

5 Maccabi World Union: International Jewish sports organization whose origins go back to the end of the 19th century. A growing number of young Eastern European Jews involved in Zionism felt that one essential prerequisite of the establishment of a national home in Palestine was the improvement of the physical condition and training of ghetto youth. In order to achieve this, gymnastics clubs were founded in many Eastern and Central European countries, which later came to be called Maccabi. The movement soon spread to more countries in Europe and to Palestine. The World Maccabi Union was formed in 1921. In less than two decades its membership was estimated at 200,000 with branches located in most countries of Europe and in Palestine, Australia, South America, South Africa, etc.

6 Hashomer Hatzair in Bulgaria: 'The Young Watchman'; A Zionist-socialist pioneering movement established in Bulgaria in 1932, Hashomer Hatzair trained youth for kibbutz life and set up kibbutzim in Palestine. During World War II, members were sent to Nazi-occupied areas and became leaders in Jewish resistance groups. After the war, Hashomer Hatzair was active in 'illegal' immigration to Palestine.

7 Burmoelos (or burmolikos, burlikus): A sweetmeat made from matzah, typical for Pesach. First, the matzah is put into water, then squashed and mixed with eggs. Balls are made from the mixture, they are fried and the result is something like donuts.

8 Fruitas: The popular name of the Tu bi-Shevat festival among the Bulgarian Jews.

9 Chifuti: Derogatory nickname for Jews in Bulgarian.

10 Brannik: Pro-fascist youth organization. It started functioning after the Law for the Protection of the Nation was passed in 1941 and the Bulgarian government forged its pro-German policy. The Branniks regularly maltreated Jews.

11 Bulgarian Legions: Union of the Bulgarian National Legions. Bulgarian fascist movement, established in 1930. Following the Italian model it aimed at building a corporate totalitarian state on the basis of military centralism. It was dismissed in 1944 after the communist take-over.

12 Law for the Protection of the Nation: A comprehensive anti-Jewish legislation in Bulgaria was introduced after the outbreak of World War II. The 'Law for the Protection of the Nation' was officially promulgated in January 1941. According to this law, Jews did not have the right to own shops and factories. Jews had to wear the distinctive yellow star; Jewish houses had to display a special sign identifying it as being Jewish; Jews were dismissed from all posts in schools and universities. The internment of Jews in certain designated towns was legalized and all Jews were expelled from Sofia in 1943. Jews were only allowed to go out into the streets for one or two hours a day. They were prohibited from using the main streets, from entering certain business establishments, and from attending places of entertainment. Their radios, automobiles, bicycles and other valuables were confiscated. From 1941 on Jewish males were sent to forced labor battalions and ordered to do extremely hard work in mountains, forests and road construction. In the Bulgarian-occupied Yugoslav (Macedonia) and Greek (Aegean Thrace) territories the Bulgarian army and administration introduced extreme measures. The Jews from these areas were deported to concentration camps, while the plans for the deportation of Jews from Bulgaria proper were halted by a protest movement launched by the vice-chairman of the Bulgarian Parliament.

13 9th September 1944: The day of the communist takeover in Bulgaria. In September 1944 the Soviet Union unexpectedly declared war on Bulgaria. On 9th September 1944 the Fatherland Front, a broad left-wing coalition, deposed the government. Although the communists were in the minority in the Fatherland Front, they were the driving force in forming the coalition, and their position was strengthened by the presence of the Red Army in Bulgaria.

14 Brigades: A form of socially useful labor, typical of communist times. Brigades were usually teams of young people who were assembled by the authorities to build new towns, roads, industrial plants, bridges, dams, etc. as well as for fruit-gathering, harvesting, etc. This labor, which would normally be classified as very hard, was unpaid. It was completely voluntary and, especially in the beginning, had a romantic ring for many young people. The town of Dimitrovgrad, named after Georgi Dimitrov - the leader of the Communist Party - was built entirely in this way.

15 Gorbachev, Mikhail (1931- ): Soviet political leader. Gorbachev joined the Communist Party in 1952 and gradually moved up in the party hierarchy. In 1970 he was elected to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, where he remained until 1990. In 1980 he joined the politburo, and in 1985 he was appointed general secretary of the party. In 1986 he embarked on a comprehensive program of political, economic, and social liberalization under the slogans of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring). The government released political prisoners, allowed increased emigration, attacked corruption, and encouraged the critical reexamination of Soviet history. The Congress of People's Deputies, founded in 1989, voted to end the Communist Party's control over the government and elected Gorbachev executive president. Gorbachev dissolved the Communist Party and granted the Baltic states independence. Following the establishment of the Commonwealth of Independent States in 1991, he resigned as president. Since 1992, Gorbachev has headed international organizations.

16 10th November 1989: After 35 years of rule, Communist Party leader Todor Zhivkov was replaced by the hitherto Prime Minister Peter Mladenov who changed the Bulgarian Communist Party's name to Socialist Party. On 17th November 1989 Mladenov became head of state, as successor of Zhivkov. Massive opposition demonstrations in Sofia with hundreds of thousands of participants calling for democratic reforms followed from 18th November to December 1989. On 7th December the 'Union of Democratic Forces' (SDS) was formed consisting of different political organizations and groups.