Otto Simko

Bratislava

Slovak Republic

Interviewer: Zuzana Slobodnikova

Date of interview: February - March 2005

Otto Simko is a man in the best years of his life, and is fully enjoying his "golden age". He actively engages in sports activities, devotes time to his hobbies and lives a rich cultural life. Within his family circle and the company of his grandchildren, he now with just a smile on his face reminisces about the many hard times in his life. He recalls what was beautiful and good. His family, friends and those close to him. Even though he's already lost many of them, they still hold a place in his heart. Many of the events in his life are moving and sad, but time has already healed these wounds. Even though they can never be completely forgotten.

Family background">Family background

My name is Otto Simko. I'm the son of Artur and Irena Simko. My name is unusual for a Jewish family [Jews living on Slovak territory before World War II had mostly German surnames, which is closely tied to the reforms of Jozef II 1 - Editor's note], which is why I decided to investigate its origins. I pondered where it could possibly originate, and came upon one thing. During the time of Austro-Hungary, my great-grandfather lived in Halic [Halic: later Galicia, is a historical territory in today's southeastern Poland and northwest Ukraine. During the years 1772 - 1918 it belonged to Austro-Hungary - Editor's note]. This means that the name Simko is probably of Polish origin. But it's quite possible that my great- grandfather changed his original Jewish name in Halic, because the name Simko isn't Jewish. According to documents that I have, my great- grandfather must have spoken German, as back then our name, Simko, was written Schimko and was written in German Schwabacher [also called Gothic, or black-letter script].

My grandfather, Albert Simko, was born in 1866 in the town of Rajcany. He had a pub in a small village named Dolne Chlebany, today it's in the Topolcany district. It was a typically Jewish pub, together with a small store. My grandparents were married on 25th August 1891. I don't know much about Grandpa Simko. I remember that he used to give me candies, just little details like that. I know that he spoke German, Hungarian and of course Slovak. My grandfather was a kulak 2. He had 40 hectares of land in Dolne Chlebany, in Rajcany and I don't know where else. I also know that my grandfather annually sent two wagons of hops to Munich.

My grandma, Malvina Simkova, nee Löwyova, was born on 11th June 1871 in Trencin. Someone remembered that her grandfather, or great-grandfather was a famous rabbi. But who it was, I have no idea. From this one can deduce that in those days these members of my family were Orthodox Jews 3 [Neolog communities 4 in Slovakia began appearing only after the Budapest Congress in the years 1868/69 - Editor's note]. I had very good experiences with my grandma. After my grandfather died she lived with us. Grandma even also brought up my daughter, Dasa. She was a very wise woman. People from all around used to always come to her for advice. Malvinéni [Hungarian: Aunt Malvina - Editor's note] was a concept. When she was 95, she was drinking beer in Zelezna Studnicka [Zelezna Studnicka: a recreational region near Bratislava - Editor's note] and someone said "Grandma, that's a beautiful age to be." She said: "What? That's a beautiful age?! Eighty, that was beautiful!". So I'm sticking to that, and when I was 80, I said to myself that this is that beautiful age that my grandma mentioned. She was of small stature, poor and those kind of people live a long time. She had gray hair. Beautiful smiling eyes. Her eyes, shone, laughed. She radiated well-being and wisdom. She had no schooling. She was a housewife from the farm. She had natural intelligence and that's what gave her personality character. Grandma Malvina died at the age of 100, on 19th May 1971, and is buried in Slavicie Udolie in Bratislava. Up to the war, Grandma was an Orthodox Jewess. After the war, no longer.

The Braun family is from my mother's branch of the family. My grandparents were named Vilmos [in Slovak Viliam] Braun and Cecilia Braunova. My grandfather on my mother's side was born in the town of Dolna Lehota, in 1850. He owned a café in Nitra. The popular Braun Café was very well known in this city. The café was located in the center of Nitra, beside the then Theater of Andrej Bagar. Unfortunately it's been since town down. They were enlarging the town square, so they leveled it. I don't remember my grandfather, he died in Nitra in 1920. That one I never knew. My grandma, Cili [Cecilia], her I remember well. She and her husband had eleven children. I think that two of them died right after birth. What my grandmother's maiden name was, that I don't know. I only know that she was originally from Nitra. She was born in 1856 and died, in 1936, in her hometown of Nitra.

The most characteristic for the whole family was Vilmos Braun. I've even got a book, named Nevet a Nyitra - Usmievava Nitra [in Hungarian and Slovak: Smiling Nitra], that contains all the anecdotes about Vilmos Braun. There are a lot of them. They're anecdotes typical of small-town café life during peacetime [during the time of the First Czechoslovak Republic 5 - Editor's note], when people had no worries. They amused themselves by playing tricks on each other and were happy when they successfully pulled off some mischievous prank.

One of the anecdotes about the Brauns says that Grandma Cili always asked: "Mikor jöttel haza? When did you come home? "I was already home at one." She didn't believe him and said to herself: "I'll get the better of you." She lay down in bed crosswise. He'll have to wake her up when he comes home at night...! In the morning Grandma wakes up, and Vilmos is fast asleep beside her. Or there was this ad in Hungarian. At night a bed during the day a 'fotel'. That's this type of folding bed. And he wrote a letter to the factory. Please sirs, I'm a café owner, I work at night and sleep during the day. Do you also have something that's a 'fotel' at night, and a bed during the day? It's full of these stories. Vilmos had a beautiful watch. "Mr. Schlessinger, I'll give this watch to you." "But why?" "My only condition is that you've always got to tell me the time. When I ask you, when I won't have a watch. You'll tell me." Schlessinger knew that something was up. But he took the watch. Vilmos let him wait for two days, after all, he had a spare watch. The third day, at 1:00 a.m., his servant is banging on Schlessinger's window: "Mr. Braun wants to know what time it is.' So by then Schlessinger knew what the deal was. That's the Braun family.

Of Cecilia and Vilmos's children, Aladar now occurs to me. He died along with this whole family in Sobibor 6. His wife Sarika as well as the children, basically the whole family died. Aladar was an extremely interesting person. At home he at first began to raise rabbits. Then he rented out a spa - Ganovce, near Poprad, and recruited children from Budapest, and also from all of Slovakia, advertising it as being in the Tatras [High Tatras: mountain range in northern Slovakia. The highest peak is Gerlachovsky Peak (2,644 m) - Editor's note]. Children from Budapest arrived there, having been sent to the Tatras by their parents. But they never saw the Tatras. Ganovce was three kilometers from Poprad [Poprad: the biggest town in the foothills of the High Tatras, with a population of 54,098 - Editor's note]. But Aladar was so clever, that he knew how to deal with them and keep them there. In the end everyone was satisfied. I also used to go there together with my brother every summer.

Here's one interesting incident with Aladar, so you can get to know the Braun nature. There was a Mr. Pazmandy in Nitra, a well-known man. He was this "degenerate' member of the upper class, simply put, a little loopy. Once Pazmandy arrived in Ganovce with his coach, or car, I don't exactly know any more. He arrived with a fishing rod. When Aladar saw him, he said to himself: "Holy moly, how in the world will I get rid of him?!" and asked him: "Pazmandy, why are you here?" "Well, I've come to catch some fish." "And what's the fishing rod for?" "I've come to fish, haven't I?" "Mr. Pazmandy, here in Ganovce we catch fish in a completely different way.' "And how, Mr. Braun?" "Well, you need an alarm clock and an axe." "And how's that?" "You put the alarm clock on the shore, and when a fish comes to have a look what time it is, you hit it on the head." To this he replied: "Sir, you have insulted me!" He turned around and offended went home. That's the Braun nature.

I'd also mention the black sheep of the family. This was Eugen Braun, a musical clown. The way it sounds. A typical musical clown, with a little violin and lots of instruments. He used to perform in circuses in Belgrade, Budapest, Sofia - all over the Balkans. A big black sheep of the family. A clown. But he was hugely successful. The king of the southern Slavs, Petar II 7 even invited him to his court. What he did is that he arrived with a large violin, broke it, and took out of it a small violin. Otherwise he also had a cello. But he didn't want to carry it around any more, and so he gave it to me, and I then had to learn to play the cello, because of him. His clown nickname was Kvak [Quack]. Because he used to perform with a trained duck. The duck was trained so that he'd put it down beside him. He'd play and the duck would quack in time, when he wanted. How he did it, I have no idea, but he had huge success with that duck. Once a terrible thing happened. He sent the duck home, and Grandma Cili slaughtered it. That was a huge catastrophe. Now, I don't want to wrong her, whether she killed it on purpose or not. But a clown for a son didn't sit well with her.

I remember, this was already in the time of the Slovak State 8. At the time Eugen was living in Romania. He said that he'd like to come home, and Grandma wrote him don't come, as things are bad for Jews here. Despite that he came. He was home for three weeks and died. He died a natural death in the hospital. As if he'd felt that he'd die and needed to say goodbye to his family. That might have been in 1942, right when the transports were taking place. He might have been about 44 or 45 years old at the time.

Another of my mother's brothers was Artur. He lived in Bratislava, in the Manderlak [Manderlak or Manderla Tower: considered to be the first so- called skyscraper in Bratislava, and in Slovakia. It was built in 1935 according to the designs of Rudolf Manderla, after whom it is named. It has 11 floors and for a long time was the tallest residential building in Bratislava - Editor's note]. He worked as a clerk for some insurance company. Later, after the war, he lived in New Zealand. Before he died, he managed to return home. He died on the plane on the way back to New Zealand. It was as if both Artur and Eugen both felt their end drawing near, and came to say home to say goodbye. Artur's son was in the English army, and after the war [World War II] the moved to New Zealand.

My mother's oldest sister was Matilnéni, alias Matilda. Matilnéni had two husbands. Her first husband was Juraj Weiss. Her first son with this husband was Kliment. After the war he was hounded by the StB 9. He died tragically, as the StB came to his apartment in Cukrova Street in Bratislava. He didn't want them to arrest him, and so he jumped out of the fourth floor. He committed suicide. Matilda's second son, Ondrej, who we called Bandi, Weiss was a musician. He used to play in cafés. He died during the Holocaust, in the gas. He was one very merry boy. See, a typical Braun. He didn't have any children. The third son, Ludovit Klein, was already from my Aunt Matilda's second marriage. He lived in Munich. He died a natural death. He survived the war in Hungary. Later he emigrated in Lima, and then to Munich. Matilnéni died of cancer, already before the Holocaust, in Nitra.

The most tragic fate was that of Serena Braunova. Sczemcinéni [Hungarian: Aunt Sczemci]. She married a man by the name of Bela Szilagyi. Bela Szilagyi was a very respected Nitra lawyer during the times of a mayor named Mojto [Frantisek Mojto]. He died already before the war, in 1937. Serena was the richest of my mother's siblings. After her husband's death she owned fields and properties in the city and its surroundings. But later, riches cost her her life. Someone told her to sell her properties, that it would save her from deportation. But as soon as she sold them - for a symbolic price, of course, they immediately put her on a transport, with the comment 'return undesirable'. Serena and Bela had no children.

Lajos [Ludovit Braun] survived the Holocaust using Aryan papers in Liptovsky Hradok, as a journalist, under the name Ludovit Bran. He kept on writing, he even published some articles, mainly a Hungarian paper. I think the paper was named Reggel. In Nitra he had a stationery store by the name of Palas. He didn't start a family, he lived with his wife, Aranka. They didn't have any children. After the war he died of cancer. Aranka then lived in Nitra in a retirement home. She died of natural causes.

The next was Hugo. He later ran the Braun Café after his grandfather. He's also illustrated in that book, Usmevava Nitra. Of course there are also some anecdotes in about him. He was in hiding during the war, but I don't know where. He died after the Holocaust of natural causes. He married before the war, and had a son, Viliam. His nickname is Bubi. Bubi lives in Munich.

Rezso, Rudolf, they called Cigi, because he was like a gypsy, completely black [from Cigan, the Slovak word for Gypsy]. I've got this impression that Grandma Cili must have had him with some Gypsy [the interviewee said it as a joke - Editor's note]. He was an amazing guy! He was very intelligent. In fact, during the war he saved me. My family, the Simkos - that is, my grandma, brother, father, mother and I, were in a camp in Vyhne. Before Vyhne we were in the Zilina collection camp. Rezso was still free. He made us a fake baptism certificate. So that we'd been converted [to Christianity] before 1938. I'd never in my life seen a priest, and neither had my family. Anyways, those who'd had themselves converted before 1938 were supposed to go to the Vyhne camp 10. It was for those in mixed marriages and Jews who'd converted before 1938. And Rezso brought a piece of paper to Zilina, that my father had been converted in 1938, so they didn't send us to the gas in the Auschwitz concentration camp, but to Vyhne. Basically, he saved us. He himself didn't manage to save himself. They then caught him in the second batch 11 and in 1944 he died.

All the Brauns had a high school education, with a natural intelligence and capable of surviving and knowing how to get ahead in life. In a word a typical vital family... Unfortunately not all of them managed to survive the horrors of the war.

My father, Artur Simko, was born in Dolne Chlebany on 31st August 1892. He's the son of Malvina and Albert Simko. He studied in Budapest. That's also this little curiosity. Jews were usually faithful to the regime that was in power at the time. Back then it was Austro-Hungary. My father was somewhat of an exception, he didn't fit into the usual Jewish stereotype. He got into Slovak society, and was a pan-Slavist 12. Sometimes he even had problems because of it, as my grandma, his mother told me that once some people came to see her and said to her: "If you don't do something about that Artur of yours, if you don't rein him in, we'll have to put him in jail." Actually, he was a dissident even back than. A Slovak against Hungarians. That's really quite atypical among Jews. In 1922 my father Artur married my mother Irena, nee Braunova. How they met and where the marriage took place, that I don't know anything about.

My mother, Irena, is of course one of the daughters of Viliam and Cecilia Braun. She was born in 1897 in Nitra. They called her Csibi. No one knew her by any other name than Csibinéni. Csibe, which means chick, that's from Hungarian. Because she was this typical little chick, merry and chipper. My mother was amazing. Unfortunately she got cancer. Just the year before she died, we'd still been skating and skiing together. In 1953 she died suddenly in Zilina of cancer.

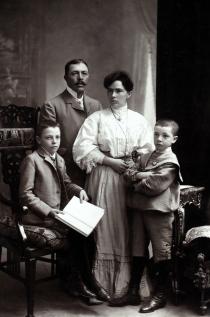

After their marriage, my father and mother moved to Topolcany. After Grandpa died, Grandma moved in with us, and became a matter-of-fact part of our family. At first my father made a living as a lawyer, but this profession didn't make him very much, as a barrister he want bankrupt. And mainly because others were charging fifty crowns an hour, and he charged ten. He was also an extremely fair person. Not very suited for the world as it was back then. Well, because he didn't succeed as a lawyer, he became a judge. They then transferred him in this job from place to place. When I was 3 years old we had to move from Topolcany to Nove Zamky. So as a three- year-old I moved to Nove Zamky. But after three years we again moved. This time to Nitra. They'd transferred my father there, and our entire family, including Grandma, had to move again. In Nitra my father worked as a judicial advisor. I don't remember much from Topolcany or Nove Zamky any more. But Nitra was my entire childhood. My mother liked to dress nicely and fashionably, and I've even got photos. My father was a judge and also dressed well.

In Nitra we had a four-room apartment. My parents had the bedroom, my grandmother and I shared a room. Another room was this fancy one, and one was a normal one. We had it very nicely furnished. Wooden furniture from the beginning of the 20th Century, leather armchairs, a dining table with chairs, a piano. They were these elegant things. I've got them to this day. We had an exceptionally large library. All this belonged to the standard our household was at. We also had a grand piano. My mother played the piano and, later so did I. I still play to this day. I can't read music, but I know how to play. Though I did take music lessons for about two years, I didn't learn much, because I hated the teacher. We had only a few things that were typically Jewish. A Chanukkah candelabra, that we definitely had. I don't know if there was a mezuzah [Mezuzah: a box for parchment that's fastened on the right side of gates and doors in Jewish households - Editor's note] on the door. We only used the candelabra during Chanukkah [Chanukkah - the Festival of Lights, also commemorates the rebellion of the Maccabees and the re-consecration of the Temple in Jerusalem - Editor's note]. Mother would play the piano and we'd sing. Though we weren't Orthodox, we cooked kosher 3. At least Grandma tried to keep it up. There'd always be barches, shoulet and other Jewish foods. On Friday we roasted a goose. First would come liver with cracklings, then on Saturday the drumsticks and on Sunday we'd have the breasts. This is exactly the way it went every week. At home we observed virtually all the holidays. There was seder [Seder: a term expressing a home service and a requisite ritual on the first night of the Passover holiday - Editor's note], Pesach [Pesach or Passover: commemorates the Israelites leaving Egyptian captivity, and is characterized by many regulations and customs. The main is the prohibition on eating anything leavened - Editor's note]. For Sukkot [Sukkot: the Festival of Tents. A singularly festive atmosphere dominates during the entire week that this holiday takes place, where the most important things is being in a sukkah - Editor's note]. My favorite was Pesach, and I also remember seder. So, for example, my grandfather kept his café open both on Friday and Saturday [The Sabbath: during the Sabbath, 39 main work activities are forbidden, from which the prohibition if others stems. Among the forbidden activities is for example "the manipulation of money" - Editor's note]. I've got this impression that he was also Neolog. For sure they weren't Orthodox, when he had his café open on Saturday, and accepted money. Not only the Jewish population visited the café. The gentry also visited it, small-town bon vivants.

Growing up">Growing up

I spent practically my entire childhood in Nitra. Very often we'd go to Zobor [Zobor: a hill by the city of Nitra (height above sea level 588 m), in the Tribec mountain range - Editor's note], both with friends and with my family. I know every corner of it there. I spent all my free time there. In the summer we'd go biking there, in the winter skiing. I always liked sports. I spent a lot of my free time doing sporting activities. At home we had a ping-pong table in the courtyard. My brother and I would often play table tennis. In those days there were two places to swim in Nitra, so we used to go swimming.

When I was 13 I had a bar mitzvah [Bar mitzvah: "son of the commandments", a Jewish boy that has reached the age of 13. A ceremony in which a boy is proclaimed to be bar mitzvah; from this time onwards he must obey all commandments prescribed by the Torah - Editor's note]. I know that I had to study with a cantor. I wasn't very good at singing, that was very bad, but I suffered through it and then some children that my parents had invited to our place came for the party. I don't think that I got a gift as such. I had only the party. My brother also had a bar mitzvah. Both of us had it in the Neolog synagogue in Nitra with Rabbi Schweiger.

My father was a judge. We didn't go hungry, but neither were we rich. I know that my father's monthly salary was 1200 crowns [in 1929, it was decreed by law that one Czechoslovak crown (Kc) was equal in value to 44.58 mg of gold - Editor's note]. That was a lot, but not again that huge an amount. The only one in the family back then to have a car was Serena Szilagyi. We also had one permanent household helper, besides the one that took care of us children. She took care of the household, cooked and did the shopping. She lived with us. I also know that she used to get 20 crowns a month.

Aunt Serena once paid for our vacation in Yugoslavia. That I remember, that she took my mother, brother plus one lady who took care of us children on vacation. We had this woman in our household that took care of us. We were in Crikvenica, by the sea. At that time I was about 7, my brother 3 years younger. I've got the feeling that Aunt Szilagyi also helped us financially. My mother was this entertaining type. I remember that when we were in Yugoslavia, below deck there was a piano, she was playing the piano and having fun, and I started crying. She was very disappointed that she couldn't play the piano. She felt good when she played. They were dancing there and I began crying and then she had to take me and leave. My mother was this entertaining type of person. She always liked to have fun, she and my father would also go to New Year's parties and I'd always wait to see what they'd bring me, what sort of balloons and confetti and things like that.

I've talked about my parents and grandparents, and we didn't get to my brother yet. Well, I wasn't a good student. My brother Ivan was always getting top marks. A much better student than I. He was very talented, and wanted to be a doctor, he was a great kid. He was born in 1927 and in 1944 he died. He was only 17 at the time. He was still this child that was growing up. This is what happened to him. You see, he was always very bold. We didn't look like Jews. He was hiding out in Nitra on Zobor and someone gave him away. Then he was in the Sered work camp 14 and before the deportations he hid in a pile of sawdust. But they found him, and then, when they were transporting them in a train to one of the concentration camps, he was apparently sawing his way out of one of the wagons. He wanted to jump out of the wagon while they were still transporting them. He tried to save his own life right up to the last moment. Unfortunately he didn't manage to. After that I didn't hear anything more about my brother.

As I've mentioned, my father was already a pan-Slavist during the time of Austro-Hungary. Then after the front, after World War I, also atypical for a Jew in Topolcany, in Koruna, he founded the Slovak National Council [Slovak National Council: the name of several high-level organs of various types during the history of Slovakia. See also 15 - Editor's note]. Koruna was the most elegant place there, a café. There were lots of Jews and Hungarians in high functions in Hungary, who were saying goodbye to Austro-Hungary and were still singing the Hungarian anthem. In the "next room over" my father was founding the Slovak National Council. My father's entire tendency was pro-Slovak, I'd say. For example, when during the war they wanted us to save ourselves from the Holocaust in Hungary, my father was against it. That was one line. The second line was social democracy [Czechoslovak Socially Democratic Labor Party - Editor's note]. He was on good terms with the minister of justice, Deder 16. My father was probably the only leftist judge in the region. It wasn't usual for judges. They were all national socialists, in short they were in the "butcher parties", they weren't in leftist parties. My father was this solo player, this black sheep. During the First Republic the Social Democrats were very active. I know that we used to go to the Social Democrats' Labor House. It was called the Labor Physical Education Union. The on the basis of this I became a shomer [a member of the Hashomer Hatzair movement. See also 17 - Editor's note]. A shomer was the closest thing to those leftists.

During the Slovak National Uprising 18 my father represented to city of Nitra at the unification congress of the Social Democrats and the Communists. That was the line, completely clear-cut, that my father took. My mother was apolitical. She couldn't care less one way or the other. She had completely different interests. And this Czechoslovak patriotism of our father's was also passed on to my brother and me. I remember composing poems about Stefanik 19. And even today, I can still recite that poem that I wrote as a schoolboy on October 28th [the anniversary of the creation of the First Czechoslovak Republic - Editor's note]. I pasted tricolors all over my chair, and recited on that chair. I still have that chair. That Czechoslovak patriotism was very strong in our family.

My father was so respected that people tried not to express any anti-Jewish comments or indications in front of him. They had to try hard. My father was the first to begin with the People's Courts 20 after World War II. It was this satisfaction for him. Nitra was the first district in the republic and my father was the first judge who began trials with Fascists and Guardists 21. For example the Guardist Gombarcik, he convicted him and I even saw his execution. He was a person who had regular murders on his conscience. Then, when the National Court ended with big trials like Tiso 22 and Mach 23, my father became the chairman of the National Court in Bratislava. He judged people like Tido Jozef Gaspar 24 and Karmasin 25, the local German boss. He also judged Wisliceny 26 - Eichmann's advisor in Slovakia!

Despite the fact that we had never hidden our Jewish origins, by our name and the way we looked people mostly didn't recognize it. In Nitra our whole family also attended synagogue, yet we didn't belong to that part of the population against whom others would have some sort of objections to. Somehow they considered our family to be good Slovaks and one of them. So in the pre-war period we never felt any anti-Semitism. We also had friends and acquaintances from mixed society, both Jews and non-Jews. So it was actually this kind of assimilation, in the good sense of the word. Certain religious customs were preserved, the Jewish identity remained. But it never came across as repellent for the surrounding population. So they accepted our family without any problems. I can say that this time was without any expressions of anti-Semitism whatsoever. The breaking point didn't come until later, at school.

The principal of the people's school 27 was Feher. An exceptionally intelligent man, who kept the school at a very high standard. Unfortunately that school building is also a sad symbol for me, because Jews were concentrated in this school in Parovce before transports from in and around Nitra. From there and the through the train station began the road to the gas. So that school actually has two faces for me. One in the fact that I attended it and had very good adventures and experiences. A few years later it was a collection point for Jews.

The first time I traveled by train it was under these peculiar circumstances. It was in people's school. President Masaryk 28 was passing through Zbehy, probably to Topolcany [Kastiel in Topolcany was the summer home of president Tomas Garrigue Masaryk - Editor's note]. Principal Feher took our class to Zbehy by train. At the trains station in Zbehy we were waving to Masaryk, and at the time Bechyne [Bechyne, Rudolf (1881 - 1948): Czech journalist and publicist, Czechoslovak socially democratic politician - Editor's note] was the minister of transport, and we were waving to him as well. It was this agitprop trip. Nitra wasn't on the main railway track. Zbehy were a railway nodal point and so we went to greet Masaryk from Nitra to Zbehy. That was my first train experience. amplified by Masaryk in the train that we were waving at. In my days people's school had five grades. I did four of them, and from fourth grade of people's school I went into high school. The building of the high school was multi- story with a large courtyard.

Before the war the Nitra Jewish community might have had several thousand people [official sources state that in the period before World War II, the Jewish community in Nita was composed of 4,363 people. According to many contemporaries of the time, the number of Jewish inhabitants in the city was higher - Editor's note]. Nitra Jews were mostly concentrated in the city quarter of Parovce, which was the former ghetto. Here there was also the famous Nitra yeshiva [The Nitra yeshiva led by a rabbi named Michael Dov Weissmandl and students that had survived the Holocaust moved in 1946 to the USA, where it exists to this day under the name Yeshiva of Nitra Rabbinical College - Editor's note]. Basically it was poor people living in Parovce. The higher and middle class lived in the center of town. Parovce was mainly very neglected old buildings, the old ghetto. There was also a mikveh [ritual bath - Editor's note] in Nitra. But we didn't go there. I don't even know where exactly it was.

When I reminisce about school days, I can't say much about high school. It doesn't have so much to do with school subjects as that at that time the nationalists were beginning to show their teeth. Those were the main experiences from high school. There were about six Jews in our class, and already there you could feel this certain, you couldn't yet call it anti- Semitism, but this certain tension. Anti-Semitism didn't rear its head until one Sudeten German 29 began teaching us, in 'tercie' [third year], I think. He came to teach Slovak, but he was a German. He was explicitly against us. He asked me: "What do you speak at home?" I said: "Slovak". "You don't speak Slovak, you definitely speak Hungarian!" and he began whacking me over the head with a newspaper. It was already obvious.

But it was in 'kvinta' [fifth year] that the main turning point came. That was in 1939. When the Slovak State already existed. Back then the following happened. We were six Jews in the class, two girls and four boys. In the morning we came to class, and written on the blackboard was the title: Jews! Then followed a long litany of all that we'd caused the Slovak nation and the conclusion "and thus we've designated the following places for you." Originally we'd each been sitting somewhere else, and suddenly they designated that we all sit together. Mendlik, our homeroom teacher, arrived. He was a Czech, and when he saw what was on the blackboard, he became extremely upset. He went to see the principal. He told him that he'd no longer be the home room teach for that class. He protested against it. Most of our high school professors were Czechs. This Mendlik taught us geography. So that's more or less how it started with that school in 1939.

During the war">During the war

I ended school in 'kvinta', in 1939. I was still allowed to attend school for one more year. I could have done 'sexta' [sixth year] but I decided for hakhsharah 30. So I went to hakhsharah, intending to aliyah to the Palestine. The hakhsharah was in the town of Radvan near Banska Bystrica [the town of Radvan was annexed by the city of Banska Bystrica and became one of its city wards - Editor's note]. I was there for one year, and absolved many jobs there. Since then I'm very good at making shoes. So I was a shoemaker. Before that I studied to be a bookbinder, so I also know how to bind books. By the way, later, in the Vyhne camp, I worked in a bagmaking workshop. There we sewed wallets and all sorts of things. I finally graduated from hakhsharah, but I didn't go to the Palestine. At the time it wasn't that organized yet and I myself decided not to go anywhere. Though I was prepared, I was supposed to first go to Denmark. I've got this large crate that was supposed to serve as a suitcase. I've still got it stored away in the cellar. In the end nothing came of it. So I stayed in Slovakia. The first guardian angel saved me when they came for me to our apartment in Nitra in 1942. Back then the non-family transports were going. It was the very first one. So they came to Seminarska Street, where we lived, for me as well. But luckily I was in Jur [Svaty Jur] at the time. We were digging a canal on the Sur River. So my father told the person that had come for me: "Otto Simko isn't here. He's working in Jur." And in this way I actually avoided deportation. That was the first guardian angel.

Once the Gestapo and the Guardists burst into Jur. It was nighttime and we were all sleeping in barracks. They came with the words: "Schweine! Hunde! Ausstehen!" [in German: Swine! Dogs! Get up!]. It was at night, and we got up. They had a list, and took boys away to the transport. At the time I wasn't on their list. But it was a sign for me that I couldn't stay in Jur any more. So I left there and returned back home, to Nitra. By then I wasn't on the list there anymore, so this is how I got through that first danger of the transports. But then, there was this thing, that they took my father to jail, to Ilava! Not as a Jew, but as a social democrat! As a political prisoner to Ilava. The transported my mother, brother and me to a collection camp in Zilina, intending to send us to Auschwitz or to one of the other German concentration camps. But they transferred my father from Ilava, to Zilina as well. That was a horrible meeting! He didn't know that we were there. And when he saw us there, that was very moving both for him and for us. For two months I was in Zilina with my entire family. Then my mother's brother, Rezso, brought a fake baptism certificate. In it, it stood that my father had been converted before 1938, and on the basis of that our entire family went to the Vyhne camp. We were actually the first transport that went through that gate not into cattle cars, but into passenger trains, which then took us to Bzenice, which is the station before Vyhne. Vyhne doesn't have its own station. From there they took us on buses to the Vyhne labor camp. In Vyhne I worked in a bagmaking workshop, where I learned to make wallets, briefcases and similar things.

An interesting thing was when we came from the collection camp, from Zilina, to the Vyhne labor camp. The head of the Jewish camp had us line up, and said in German: "You were all converted before 1938." To this one voice: "Not me, not me!" Everyone stood in shock, wondering who was shouting that. It was a proletarian from Bratislava, Willy Kohn. A notorious Bratislava character. He also got into the Vyhne camp, but not because he'd been converted, but because he had an Aryan wife. Because they were also sending people from mixed marriages there. "I got Aryan wife! I got Aryan wife!" You see, Willy didn't speak Slovak well. He was a Presporker [Prespork, or Pressburg - the German name for Bratislava - Editor's note] and didn't speak Slovak. To that was this first funny incident, gallows humor.

Vyhne was known for having a boss, Gindl, who had this specialty, when someone did something, he got 25 on the whipping horse. He had a whipping horse set up there. A certain Guardist named Ondra used to give out 25 blows. He had this little boat and we called him the little brigadier. But Gindl was then let go, and Leitner arrived. He was a soldier, and he was much more decent. After his arrival the conditions in the camp got a bit better. We were in the Vyhne labor camp for ten months. Then my father got a departmental exception. Back then the minister of justice was a certain Fritz [Dr. Gejza Fritz]. He arranged for him to be employed in Trstena. He was responsible for the Grundbuch [in German: land register - Editor's note]. Polish towns that had fallen under the Slovak State needed to arrange some things in the land registry, and they put him there because of that. We were very glad to be able to leave.

But here's the way it was. Back then the transports weren't running anymore. It was this in-between time. When the transports had ended, and the next ones hadn't started yet. Those who were out, were afraid that they'd take them to Sered, Novaky or to Vyhne, but those who were already in a camp, they were content, because the transports were no longer running. But that Damocles' sword [metaphorically speaking, a symbol of ever-present danger - Editor's note] was still hanging over us. So in that sense it was good that we could leave that camp early. Otherwise, I've got this very interesting document from that camp. I think it's the only one, because labor camps didn't issue documents. The Jewish camp leadership, namely Mr. Wildmann, issued it to me. I had asked him for confirmation that I'd been in that camp. The confirmation sounds typically thought through in a Jewish fashion: "According to legal regulations. We cannot issue you a report regarding your employment in our Jewish labor camp, although during your stay from 18th October1942 to 31st August 1943 you proved very satisfactory in our bagmaking workshop." They gave me a confirmation that says that they can't issue me a confirmation, although you from, to... in a word, I loved that idea. So I'm the only one to have a confirmation from that camp.

From Vyhne I went home, to Nitra. But the times were uncertain. I decided to get a job using so-called Aryan papers. I had a fake birth certificate, on which I didn't even have to change my name. With these papers I got a job as a bookbinder at the Hlavis Company in Liptovsky Mikulas. I went there alone, without my parents and that's where I was when the uprising 17 came along. So I immediately volunteered for the uprising and was a member of the 9th Liptov Partisan Division, in the Liptov Mountains. One thing has remained in my memory above all. There were five Jews in our division. We also slept in one tent, and everyone knew that we were Jews. We felt great during all the missions, as we felt this satisfaction, that now we had rifles in hand. We were no longer persecuted. Now we were equal. In short it was this feeling of amazing rebirth of your own person and also self-confidence.

The most powerful feeling was when one of my Jewish friends, Gabi Eichler, now he's in Israel and is named Gabi Oren, who was the boldest of us all. He was in the town of Vitalisovce at the time. The rest of us were in Zdiarska Dolina [the Zdiar Valley], in a cabin. In Vitalisovce he captured a German officer, and brought him to us in the cabin in Zdiarska Dolina. After a detailed interrogation it was ascertained that he was a guard from Dachau 31, a member of the SS. The result couldn't be anything other than execution. As partisans we couldn't take prisoners along with us. Execution as decided on, and the political commissar, Galica, picked two Jewish boys, me and another one, for the execution. Galica went with us as well. We went with that German up above the cabin, a little ways off, and there we told him to get undressed. We still needed his uniform. I even tried to explain to him in German why he had to die. He reacted: "I know what's going to happen to me. I'm still loyal to Hitler. I don't regret anything. Not even from the concentration camp, what I've done, with Jews. That was my belief, that it's right." In short, he felt to be a member of the SS up to the last moment. He didn't want to regret anything. Of course, for me it was then easier, and even that shot came out easier. I'd never shot anyone from such a close distance before. I shot a person who really did deserve it, when you think about it. Well, and later I almost paid the price for that execution.

Later our partisan division, at the Zdiar cabin, was scattered by the Germans and we had to retreat across the hills to Rohac. One of the Jewish boys, Janko Pressburger, was wounded. Now he lives in the town of Ber Sheva, in Israel. Two of us carried him through the mountains. We lost our unit. We were then hiding out in Pribilina, and I went to Liptovsky Mikulas dressed as a civilian. I knew that the director of the hospital there, Droppa, hid partisans and Jews by pretending that they were patients. My task was to get our wounded friend into the hospital there. Well, in Liptovsky Mikulas I was caught by a Guardist by the name of Kruzliak. He checked my ID, but my papers weren't in order. He began asking questions, who I was, what I was. I had to pull down my pants in front of him. When he saw that I was circumcised, they threw me in jail right away. I was locked up in the local jail. When in the meantime the Germans arrived in Zdiarska Dolina, they exhumed that executed German. In the jail they were investigating what had actually happened, who had done it. Someone gave away the fact that I'd been in that partisan division that had executed him. So they investigated me in connection with the execution. I of course knew that if it came out, I'd be dead. I denied ever having been there. That I'd never even been a partisan and didn't know about it and so on. The beat me a lot, and wanted to get it out of me by force. But at this time my German helped me a lot. One SS soldier said to my interrogator, who was called Barnabas Magat: "I'm not sure about that little guy." By the little guy he of course meant me. They didn't know that I understood German. His doubts about my guilt buoyed me and despite a heavy beating I kept denying it.

In jail it was scabies that helped save me, when I think about it. Because I got scabies, and when the Red Cross arrived, they decided that I have to go to the hospital for treatment. Two militiamen led me at bayonet-point to the hospital for treatment. I told the nurse, when she wanted to take my clothes: "Leave my clothes here. I want to escape. And please, prolong the treatment for as long as possible." That was in December of 1944. So the militiamen waited for me in front of the washroom, and I opened the window and hightailed it away from the hospital. Then I got to Nitra and hid out there in the Mr. Truska's cellar. The way it was, was that I went to see one acquaintance that knew that my father had been a social democrat before. He sent me to another place, and from there they again sent me on. Until finally that Truska took me in. He had a bunker in the cellar, and there were about ten Jews there. All Orthodox Jews. I arrived there, everyone there had a beard, and the first thing they asked me was what was up with the rabbi. But I didn't know what was up with the rabbi.

My father was also in the mountains from the start of the uprising. My mother and grandma were in hiding in Nitra. My brother was also in Nitra in the beginning, but they then took him away. My mother and grandma were saved. They were hidden in the same place. I knew where they were hiding out. I knew that they were alive. We didn't know about my father, just like we didn't know about my brother's further fate. So liberation was actually this bittersweet affair. My father returned. But we were waiting for my brother. That was the worst disappointment.

Post-war">Post-war

Luckily we were able to return to our old apartment. We discovered that the Germans had had a casino in our apartment. The furniture was there, but the neighbors had looted everything else. But the apartment was there, and that was enough for us. We had someplace to come back to. Then also many of those that were returning lived with us, as we were the only ones who had at least some sort of haven. We had enough to be able to live. As soon as we returned to the apartment, I went down to look in the cellar. There were about fifteen people hiding there, because just then they were bombing the city. I was an excellent shelter from the bombing. Well, they were completely horrified when they saw me, because many of them had the things that had been taken from our place. But back then I didn't care about things. I know very well that they were very horrified that I'd returned.

But basically no one took an openly negative stance towards us. My father's position in Nitra was such that no one dared to in some way show some sort of hate, or something similar. Right away he was a people's judge in Nitra. When the people's court began to hold sessions, they didn't want to start anything with us. We also weren't out for revenge. What was important to us was for my brother to return. But that didn't happen. So that's how we survived the war. I had to graduate from high school by taking an accelerated program in Bratislava. After the front I moved to Bratislava. I didn't have anything in common with Nitra anymore. My father and mother stayed in Nitra along with Grandma. Only I was in Bratislava, studying. My father became the chairman of the Regional Court in Zilina. So my parents moved from Nitra to Zilina. In time my father became the chairman of the Regional Court in Bratislava. in 1953 my mother died of cancer, and is buried in Zilina at the Jewish cemetery. She had a proper Jewish funeral.

The Slansky trials 32 didn't affect my father in any special fashion. But something worse affected him. The justice minister was one very well known Jew, by the name of Reis. He was Gottwald's 33 good friend, a Communist. My father was the chairman of the Regional Court in Zilina, and this Reis stripped him of his position of chairman and designated a different person, a worker cadre, who started working there as the chairman of the Regional Court. Back then it wounded my father very much.

After arriving in Bratislava I finished high school by taking an accelerated program, and registered at Comenius University in Bratislava, at the Faculty of Law. So I was a law student. From 1945 to 1949. I got a break, because as a partisan I was credited with one year, or two semesters. So I studied law for only four years. Otherwise, studying law consisted of going to lectures. Some went, some didn't, you just had to pass the exams. I rented a place with two other classmates. Well, and then I finished my studies. Then I got a job at the Commission of Social Affairs. Later, already as a doctor of law, in the legal department. So I was there, but later I then led the education division at the Labor Commission. That lasted until the 'Slanskiade' [the Slansky affair].

Well, then there was that sort of intermezzo, that the Slanskiade had arrived. Suddenly I was working as a lathe operator in Martin. That was in the year 1951. Then I was a teacher in a home for apprentices, as they needed me there. Later I also worked as a 'labcor', or labor correspondent. As a worker I wrote various contributions for Prace 34. As a labcor they sent me for schooling, the fact that I was just by the way already a doctor of law didn't trouble them. But as a labcor, pretty please, I did well and they accepted me onto the staff of the daily paper Smena 35. In 1954 I started working in the offices of Smena in Bratislava. At first I worked in the labor department, then later mainly in the foreign department. I didn't have anything to do with law anymore. Law didn't come in handy until they threw me off the staff of the paper, after Party screenings. In 1971, a couple of years after the arrival of the "brotherly armies" 36, I was thrown off the staff.

Finally I got a job as a company lawyer in one construction company in Bratislava. It was named Staving. Here it finally came in handy that I had studied law. I was a company lawyer, I used to go to meetings. I represented the company against employees. But it always ended well, because I always came to an agreement with the employee. He either withdrew his claim, or we came to some other agreement. I actually worked in Staving up until retirement. I was about 60 when I began working and retired. In retirement I again began writing for newspapers. After the war I never met up with anti-Semitism again. I think that in this respect I've got good experiences, I never had problems of this type.

Before the war I was a Neolog, a normal thing. After liberation, very many Jews, including me, saw a certain solution in leftism, Communism. So I don't have a relationship to Judaism through religion. Which is typical for people of my type, a common fate, past. All this brought me to Judaism, in that now I'm quite active in the B'nai Brith and Hidden Child organizations. So there I found myself. I entered the Jewish religious community in Bratislava about two years ago [i.e. in 2004 - Editor's note]. Even before that I participated in all events, but didn't formally join the community. But then I felt a summons, that I must fulfill this formality as well. Even though with me it has nothing to do with religion.

I'll mention my personal life after the Holocaust only very briefly. Back in those days there used to be company vacations to Bulgaria. From the Labor Commission I also want on vacation to Bulgaria. There I met my wife. She was a medical lab technician in the Tatras, in a sanatorium. For a long time nothing happened, but then it ended up with us getting married. She was named Matilda Podobnikova. She was from the Gemer [region], from a little village named Lubovnik. She was from a family with many children, there were six or seven of them. Her first name was officially Matilda, but everyone called her Mata. They then combined it with the famous Mata Hari [real name: Zelle, Margaretha Geertruida (1876 - 1917): a notorious dancer and courtesan. During World War I she was convicted of espionage and executed - Editor's note] and everyone called her Harina, Harnika or Hari. She wasn't Jewish. No one in her entire family was Jewish. Despite my origins, there wasn't even a pinch, not even a hint of some verbal slip, that they objected to my being a Jew! That was something amazing, as far as their relationship to Jews went. I really did find a family where it played absolutely no role.

Matilda and I were married in 1954 in Bratislava. Just at city hall. She worked in the Tatras, even when we were married. I worked for the paper in Bratislava. Then Matilda came to live in Bratislava. At first we lived in hotels, we didn't get an apartment until later. In the meantime my father and grandma moved here. They rented a place, finally they came to an agreement with the owner, and bought the apartment from him. My wife and I lived there with our little daughter who'd been born in the meantime, with my father and my grandmother. My wife died in 1996. She was five years older than me.

My wife and I had one daughter. She was born exactly two years after our wedding in 1956, and we named her Dasa. Dasa wasn't brought up in the spirit of Jewish traditions. She knows who her father is, and what fate befell his entire family. My wife and I didn't observe any Jewish customs. We had a normal household. I continued to be inclined towards Judaism, but only alone. I didn't lead my daughter to it.

My grandma died at the age of 100. That was in 1971, and that was a period when she couldn't have a Jewish funeral, and is buried in Slavicie Udolie. My grandmother, who would have deserved it the most, didn't have a Jewish wedding. My father died in 1976, also here in Bratislava. He also had a civil funeral, and his ashes are scattered over the scattering meadow of the crematorium in Bratislava.

Because I'd been thrown off the staff of Smena, they didn't want to accept my daughter into university. She wanted to be a pharmacist. So at first she went to Prague, into a so-called zeroth year. Then they just barely accepted her into mechanical engineering, but she was there only a half semester. They then accepted her to the Faculty of Chemistry, where she was for about six semesters, but she said that she wouldn't work. so they finally gave her Russian and Bulgarian at university. There she even completed a doctorate and worked on Russian-Slovak and Bulgarian-Slovak dictionaries at the Language Sciences Institute. Currently she's working with schola ludus [schola ludus: a civic society whose main goal is the support and systematic development of lifelong, informal education, mainly in the sphere of natural sciences, the support of scholastic education in the sphere of general scientific and technical literacy - Editor's note], that's this one organization where they educate children in physics and chemistry.

Her husband is the actor Petr Simun from the Astorka Theater. Recently I attended one amazing performance, Eve of Retirement. It's a symphony of acting, playing in it were Kronerova, Simun and Furkova. Though there were only three actors on stage, but it was worth it! It's all on a Jewish theme. The play is very successful. My daughter has two children. My grandson is named Palko [Pavol] and my granddaughter Barborka [Barbora]. We see each other almost every day. They come here, then I go see them. In short, as if we lived together.

In retirement I make use of my free time and enjoy life. Four times a week I go swimming, which is a good thing. I inherited these sports activities of mine from my mother. She also had an all-around talent for sports. Until recently I also used to go skating. Of course, I also devote myself to cultural events. I have enough time, so I try to use it to the fullest. For suffering during the Holocaust, I get compensation monthly, and also something from the Claims Conference. But I've got to say, that given my modest lifestyle, I don't have these types of problems.