Mina Gomberg

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Elena Zaslsvskaya

Date of interview: September 2002

Minna Gomberg is a plump and handsome woman with grayish hair done in tidy manner. She is vivid and sociable. She loves to talk about her relatives. She has created a very warm household and nice relationships with her husband and children. There is a strong Jewish spirit in their apartment. Minna speaks Russian with a Jewish accent and often uses Yiddish words. They are a wealthy family. Their apartment is nicely furnished. There are expensive carpets, chandeliers and household appliances. The apartment is very clean and things are kept in good order. They have a pet: a big black cat. The members of the family spoil it by buying good fish or meat for it.

My family background

Growing up in wartime

My school years

My husband

Our children

Glossary

My grandfather on my father's side, Joseph Roitman, was born in 1880. At the beginning of the 20th century his family moved to Podol 1 in Kiev from some town, running from pogroms 2 and gangs. Podol was in the Pale of Settlement 3, where Jews were allowed to live. My grandfather was a tailor and had many clients.

His family lived in a small apartment, but they were a wealthy family. There was no luxury in this apartment, and the toilet was in the yard. They all had comfortable beds, a big cupboard and a wardrobe. They could afford to buy chicken on holidays, but most of the time they had basic food: vegetables, beans and bread. My grandfather arranged his workplace in one of the rooms. He had some education. I believe he studied in a cheder, but he didn't have any professional education. He was religious. He celebrated Sabbath and all holidays. He went to the synagogue once a week on Saturdays. My grandfather only spoke Yiddish.

My grandmother on my father's side, Reizl Roitman [nee Zhelezniak], was born in 1882. I don't know where she was born. She didn't study anywhere but she could read and write. She spoke Yiddish, or say, a mixture of Yiddish and Ukrainian. She was very tiny. My grandmother was a housewife and she kept my grandfather's workplace in good order. She was very religious. She always wore a shawl and went to the synagogue with my grandfather on Saturdays. My grandparents had three children: Jacob, Ilia and a daughter called Bluma. They were all born in Podol.

Jacob Roitman was born in 1906. He finished secondary school and had higher education. I don't know where he studied. He worked at the Bolshevik plant in Kiev and became a chief production engineer at the end of his career. He worked at the plant during the war and evacuated with the plant. He died in Kiev in 1975. His wife, Lyusia Roitman, and his son Boris live in the US.

My father's sister, Bluma Roitman, was born in Kiev in 1912. She finished secondary school and took a course in accounting. She worked as an accountant. In the middle of the 1990s she and her daughter moved to the US. Bluma died there in 1999. This is all the information I have about her.

My father, Ilia Roitman, was born in Kiev in 1909. He finished cheder and a Russian secondary school in Kiev. After finishing school he entered some technical college, but he only studied there for a short time. The family was pressed for money, and he had to work to support them. My father worked as a laborer wherever he could find a job. In 1939 he was recruited to the army and involved in the Finnish campaign 4. His service lasted for about a year, and he returned home afterwards.

In the middle of the 1920s, after residential restrictions were abolished, my grandfather and his family moved to a bigger apartment in Kiev. They became poorer because not many people could afford to pay for new clothes, and as a result my grandfather had fewer clients.

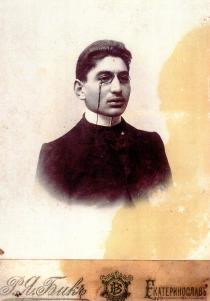

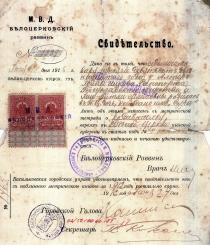

My grandfather on my mother's side, Alter-Iona Rapoport, was born in 1880 in Belaya Tserkov [a small town 100 km from Kiev]. The Jewish community of Belaya Tserkov was founded in the 16th century. In the middle of the 18th century the town was one of the centers of Hasidism 5. Jewish families owned 230 houses by the end of the century. There were also many Ukrainian families in town. The town-people were mainly involved in commerce, selling cattle and bread. There were also a sugar factory, a tobacco factory, food factories and 250 crafts shops in town. In the middle of the 19th century the town had ten synagogues. There was a Jewish School of Commerce and a Jewish hospital in Belaya Tserkov at the end of the 19th century. Life was good until 1905.

But there were a number of pogroms in 1905. Many Jewish families perished at that time. Every now and then pogroms took place in various areas. The pogroms were happening continuously between 1905 and 1919. I only know the number of people that perished between 1917 and 1919: 850 Jews.

My grandfather received some education, but I don't know where he studied. He was chief accountant at the sugar factory before 1917. He was a respected and talented man and provided well for his family. They lived in a big wooden house with two rooms, a kitchen and a hallway. They kept a housemaid. They also had a garden and a kitchen garden. They didn't keep any livestock - they could afford to buy all necessary products. Their family wasn't ultra-religious. The men didn't wear payes, and other members of the family wore casual clothing. On holidays the men wore white shirts and long jackets. The women wore long dresses with laces and frills.

They observed Jewish traditions and celebrated Sabbath and holidays. They dressed up to go to the synagogue and had nice dinners with their friends and relatives afterwards. Going to the synagogue was more of a tribute to tradition than profound faith to them. I like to recall the 1900s when it became a habit in our family to have coffee in the evening. On Friday evening the family got together on the veranda in summer, or in the living room in winter, for a coffee party: they got together to talk and enjoy their time together. There wasn't any connection with Sabbath, but it was nice to take a rest from the routine of weekdays. Coffee was imported into Ukraine and only wealthy families could afford to buy it.

My grandmother on my mother's side, Clara Rapoport [nee Kolodnaya], was born in Belaya Tserkov in 1882. She had some education. Her mother tongue was Yiddish, but she could also speak Ukrainian. She was introduced to my grandfather by a matchmaker. My grandparents got married in 1904. They had a big wedding with a chuppah, many guests and klezmer musicians. My grandparents had six children: four daughters called Minna, Dvoira, Eta and Surah, and twin sons that died in infancy.

My grandfather died of typhoid in 1919 at the age of 39. We tried to find his grave in the 1950s, but there was a road built over the Jewish cemetery, and the graves had not been removed to a different location. After his death my grandmother and her four children used to hide at their Ukrainian neighbor's house, because they were afraid of the pogroms. In the late 1920s my grandmother had pneumonia and moved to her daughter Dvoira in Kiev. Dvoira was married by that time. My grandmother died in 1938. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Kiev.

My grandmother's older daughter, Minna Rapoport, was born in Belaya Tserkov in 1907. She studied at the Jewish grammar school. In 1928 she fell seriously ill and died. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Belaya Tserkov.

Dvoira Rapoport was born in Belaya Tserkov in 1909. She went to a Jewish school. In the late 1920s she visited her younger sister, who was studying at a technical college in Kiev. Dvoira met Abram Yankovskiy in Kiev. He was a convinced follower of Lenin's ideas and one of the founders of the Komsomol 6 League in Ukraine. At that time Dvoira began to introduce herself with a Russian name: Vera. She married Abram in 1927. They didn't have a religious wedding. They had a civil ceremony.

Dvoira and Abram were both convinced communists, and the celebration of any Jewish holidays in their house was out of the question. Their daughter Natasha was born in 1928 and in 1933 they had a son, Alexandr. The children were at different children's homes. In the 1930s mass arrests 7 of party leaders took place. At the beginning of 1935, before leaving for Moscow to attend a Komsomol Congress, Abram told Vera to burn all his photographs, notebooks with his notes and any documents that they had at home. He understood that there was a blood shedding campaign against devoted communists going on in the country and tried to keep his family and his acquaintances safe. He didn't want any information about his people become known to the NKVD 8 officials. He never returned home. He was arrested during the Congress as an enemy of the people and executed. He was accused of betraying the ideals of communism and of collaboration with foreign intelligence forces.

In 1937 Vera was arrested as wife of an enemy of the people and sentenced to ten-year imprisonment in a camp in Kemerovo region [1,700 km from Kiev]. She was accused of concealing her husband's subversive activities. She was in the camp until 1947. She worked there sewing uniforms for the military. Vera stayed at a women's camp and there was a men's camp nearby. Vera told us that when women went to the sauna they pretended that a tap was broken to be able to call a plumber from the men's camp. Many of the women had their husbands in that camp, and the plumber gave them news about their husbands while fixing the tap. The inmates of the camp were allowed to receive one letter per month. Vera's son, her daughter and her relatives took turns writing to her.

Vera was released in 1947. She was allowed to have her children back. She wrote to her children, telling them to get together at the Yaya station in Kemerovo region. A woman living in the village of Yaya went to pick up Vera's son; she had the address of the children's homes where Vera's children were kept. Natasha, the older child, was to come by train alone. Vera's children hadn't seen each other since 1937. Brother and sister were going on the same train but didn't recognize one another. They met on the platform when they both approached their mother. Vera worked as a laborer in Kemerovo region until 1954. She was not allowed to live in bigger towns. Her son went to school, and her daughter studied, but I don't know where.

Vera returned to Kiev in 1954. She worked as a laborer and died in Kiev in 1965. Her son Alexandr graduated from the Polytechnic Institute. He became chief engineer at the Kama Power Plant. He died in Perm in the 1980s following a kidney surgery. Vera's daughter graduated from the Institute of Steel and Alloys in Moscow. She got married and moved to Cheliabinsk with her husband. She worked at the metallurgical plant there. She retired recently.

My mother's third sister, Eta Rapoport, was born in Belaya Tserkov in 1910. She finished secondary school in Belaya Tserkov and married a Ukrainian man - his last name was Tkachenko. Her husband was a very intelligent and decent man. There were no objections in the family against Eta marrying a non-Jewish man. The family knew that he was a good man and that was enough for them. Eta and her husband lived at their parents' home. Their son Alexandr was born in 1941, and in 1945 they had a daughter, Natasha. During the war they were in evacuation, but I don't know where. Alexandr graduated from school with a gold medal [for graduation with honors from high school] and studied at Kiev University. He's a Doctor of Philology and writes scientific articles. Natasha quit university after two years of studies. She works as a computer operator at a plant in Belaya Tserkov. Eta died in Belaya Tserkov in 1987. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery.

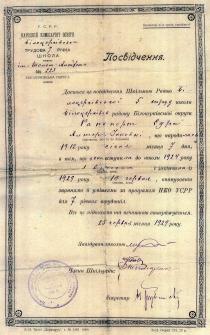

My mother, Surah Rapoport, was born in Belaya Tserkov in 1912. She studied at the Jewish primary school and then went to the Jewish lower secondary school named after Sholem Aleichem 9. She finished school in 1929. In 1930 she moved to Kiev, where her sister Vera was living at that time. My mother went to work as a laborer at the Kiev radio plant. In 1931 my mother became a Komsomol member, and in 1932 she became a Communist Party candidate. She also became a Komsomol public propagandist at the radio plant. She propagated the Komsomol among young people, explaining its ideas and goals to them.

My mother was a very kind and, at the same time, very active person. She had sincere faith in the communist ideals and loved her official activities. In 1935, after the arrest of her sister's husband, she was expelled from her candidateship in the Communist Party at a meeting of the party unit of the plant, where she was working at the time. [There was a Communist Party unit at every enterprise at that time.] She was accused of concealing the activities of Abram Yankovskiy from her party leadership. This was a very serious accusation at that time. It was impossible to prove that a person wasn't guilty. The decision of her party unit was very dramatic for my mother. The Party was her life, and she began to appeal to the Party's higher offices to have her accusations withdrawn. She went to Moscow and her case was reviewed at the Party Control Commission meeting. They cancelled the decision of her party unit, and my mother returned to the plant.

I don't know when and how my mother met my father. They got married in 1937, and my mother moved to her husband's apartment, where his parents were also living. As far as I know they had a civil registration ceremony and no wedding party.

I was born in 1938. I was 3 when the war began in 1941 10. My mother was secretary of the party organization at the plant. The plant was evacuated, and we moved along. I remember our trip on the train. It was a long and tiring journey. We were in evacuation in the town of Artymovsk Egorshyn, Sverdlovsk region [2,800 km from Kiev]. We - my father's parents, my mother and I - lived on the second floor of a wooden house. My father went to the front on the first days of the war. We knew that he was in a tank brigade, and he wrote to us every now and then.

My mother kept her post as secretary of the party organization at the radio plant during the war and, being a party official, she received packaged food. I even had chocolate during the war and shared it with my friends in the yard. I went to kindergarten in Artymovsk. I liked it there. I got along well with the children, and our teachers were kind to us. My grandmother took me to kindergarten every morning. My mother had always left for work by that time.

My grandfather caught a cold that developed into pneumonia. He was taken to hospital for treatment, but he died there. Before the funeral my grandfather's body was taken home, and I cried and screamed demanding that they let me see him, but I was held back. I loved my grandfather, and his death was a terrible blow to me. He was buried at an ordinary cemetery in Artyomovsk. There was no Jewish cemetery in this town, because there were no Jews living in it before the war.

I remember very well how my mother spoke on the radio in November 1943 when Kiev was liberated. I heard her voice on the radio and was shouting into it, 'Mother, answer me - I can hear you!' Many people came into the streets to rejoice. They were laughing and hugging each other. My mother got instructions to go back to Kiev. We couldn't follow her until we got the official permission from the authorities that she obtained for us. My grandmother and I returned to Kiev in the spring of 1945.

My mother lived in a room in a three-bedroom apartment. There was another female tenant in the apartment, who occupied the two other rooms. She was the widow of General Pavlov, who perished during the war. [General Pavlov was the commander of the Western Front. During the German aggression, in June 1941, he displayed grave incompetence and negligence. The result was the loss of Minsk, the Belarus capital, on June 28. Stalin recalled Pavlov and his staff to Moscow. They were tried and shot.] In 1945 an order to return apartments to war veterans or their families was issued. Pavlov's widow demanded that my mother moved out of the apartment. My mother and grandmother moved to my mother's office at the district party committee, and my mother's friend took me to live with her. Eventually my mother managed to get back my paternal grandparents' apartment. This happened before my father returned from the army at the end of 1945.

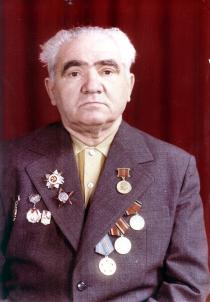

My father wrote us letters all this time. He was a tank platoon leader; he was in control of four tanks. He liberated Prague with his units and had the rank of first lieutenant. He was wounded twice. The first time he was wounded on his left hand, and his fingers didn't bend after this injury, and the second time he had an eye injury. But we knew that he was alive which was most important and that he could demobilize when he was allowed to do so. My father demobilized in 1946. He got a job as a foreman at the Vodokanal municipal water-supply company. He worked with Vodokanal until 1984.

My father received an apartment in a shabby wooden house at the end 1946. It had a big room and a kitchen. There were two beams in the kitchen supporting the ceiling, which was about to fall on our gas stove. We were living from hand-to-mouth. We didn't starve, but my parents had to borrow money from a neighbor in order to tide them over until their next payday at work.

I went to Russian secondary schooling Kiev. I did well at school. I became a pioneer when I was 9 and a Komsomol member when I was 14. I took part in various activities at school. I was responsible for the wall newspaper at school. I was also a pioneer tutor in the 1st grade. I took the children to museums and theaters and arranged parties for them on New Year's and on Soviet holidays. When I was in the 4th grade I was elected chairman of the school pioneer unit, and I was a member of the school Komsomol committee.

I had many friends at school. My closest friends were Nelia Vakulenko and Inna Geizer, two Jewish girls. Nelia's parents worked at an office, and Inna's parents were workers at one of the plants in Kiev. I had no more contact with them after we finished school and thus don't have any information about what they did later. While at school I spent my summer vacations in the pioneer camp Smena near Kiev. I liked it there and stayed in the camp as long as I could. We went swimming and lay in the sun and participated in all kinds of activities such as games and sport competitions. I also read a lot. I read fiction, love stories and Russian and foreign classics.

I don't remember any demonstrations of anti-Semitism at school or in the camp. We believed everything the official propaganda told people about the prompt victory of communism all over the world and about the leading role of the Communist Party in the struggle for communism. My mother was a dedicated party official and had no other thoughts but those about Marxism- Leninism.

Israel was established in 1948. I remember my mother and father whispering something to one another. I could only hear the word Israel several times. My parents were very happy about this event, but they were reluctant to give me any clues about it. I was still a child and could have said something at school, or elsewhere, and this was very dangerous at the time. Everybody was grieving when Stalin died in 1953. We thought it was the end of the world. We were brought up thinking this way.

My father's mother was living with us. She was very religious. She fasted at Yom Kippur. She gave me Chanukkah gelt [money]. My grandmother celebrated Sabbath. She lit candles and said a prayer. On the day of my grandfather's death she lit a kerosene lamp and left it on for a whole day. Pesach was very festive. My grandmother used to bake matzah before Pesach. She also cooked beetroot soup with matzah and gefilte fish. We didn't follow the kashrut at home, but my grandmother had special bowls and plates that she only used at Pesach. There was no special ritual on this holiday, and we didn't read the Haggadah, but the whole family always got together, and we had our Jewish friends joining us. We were all dressed up and enjoyed the celebrations. Older people used to meet near the synagogue at Yom Kippur to discuss the dates of upcoming holidays and other events. My grandmother also went there.

My parents showed understanding of my grandmother's religious convictions. They always attended family celebrations. My mother always helped my grandmother to cook Jewish food.

My mother was very lucky that the struggle against cosmopolitism 11 in the late 1940s bypassed her. Her party boss valued her for her organizational talents and responsibility. He was an intelligent and smart man, and he protected her from any possible persecution.

I finished school in 1953. At that time it was next to impossible for a Jew to enter a higher educational institute in Kiev. We knew some very smart and talented children of my father's friends failing to enter institutes. Each time after exams they were told that they failed to win in the 'competition of grades' [it was necessary to get a certain number of grades based on the results of entrance exams], but it was clear that the reason was their Jewish nationality and anti-Semitism in the country. I went to the Pedagogical Institute in Leningrad. I passed my entrance exams with two '5' grades [highest] and two '4' grades [good], and the total sum of these grades wasn't sufficient to win the competition. I was ashamed to go back to Kiev with such poor results. I entered the Faculty of Electronics at the Electro Vacuum College in Leningrad. I rented a room for 20 rubles - that was half my stipend. I fell in love with the beautiful city and spent all my free time in museums and theaters. My parents sent me some money. I mainly had non-Jewish friends. I only communicated with them while studying in the College.

In 1958 I returned to Kiev and lived with my parents in the apartment in the old shabby wooden building that my father received after the war. I started looking for a job but couldn't find any. The moment human resource managers opened my passport and saw that I was a Jew they were telling me that there were no vacancies left. My mother, who was a high party official, had already asked her boss to call the director of the Radiopribor factory and pull strings for me. Although I held a diploma in electronic technology, I was offered the position of a packer at the storage facility. My career started when the production manager came to the storage facility and noticed me because of my smart answer to one of his questions. He offered me a job in his production-planning department.

In 1962 I entered the Faculty of Wire and Wireless Communications at the Odessa Communications Institute, where I studied correspondence. I had tried to enter it twice before, and I was successful the third time. After I got my diploma I was appointed manager of the planning-dispatcher bureau of the shop and later became a senior forewoman at the Radiopribor factory. This was the highest position I was promoted to. I suffered much from anti- Semitism. I didn't feel it when I was among common employees, but it was so evident when I had to deal with the management. They gave me polite hints that my career would have been different if it hadn't been for my nationality.

In 1959 I married Arnold Gomberg, a Jewish man. I met him at my friend's wedding in one of the Kiev restaurants. We had a civil ceremony and invited our guests to a dinner my mother had prepared. We had about 15 guests: my husband's and my friends and some relatives.

My husband was born to Vladimir and Dora Gomberg in Kiev in 1934. His grandfather on his father's side came from the town of Khodorkov, Zhytomir region [about 150 km from Kiev]. There were about 4,000 Jews in the town of Khodorkov at the end of the 19th century. In the middle of the 19th century a distillery and a big sugar factory were built in Khodorkov. There was also a sawmill, a soap factory and two water mills. There were three private Jewish schools and yeshivah. There was a cheder and a few synagogues in town. The main language of communication was Yiddish.

My husband's grandfather, Aron-Hertz Gomberg, worked at the sugar factory in Khodorkov. He was supervisor of the transport department, which consisted of 13 carts, 14 horses and 15 drivers. My grandfather had 14 children. My husband told me that his grandfather's family was religious. They celebrated Sabbath and all holidays. They went to the synagogue and prayed. They spoke Yiddish in the family, and his grandfather also knew Ukrainian. His grandfather died before 1917.

My husband's grandmother, Dvosia, was born in Khodorkov in 1869. She had no education and couldn't read or write. She was a housewife and raised her children. She only spoke Yiddish. She had a strong will and was a strict person. After the revolution of 1917 one of her sons took her to live with him in Kiev to save her from pogroms. In 1941 she evacuated to Middle Asia with her daughter Genia. She died there some time in 1944.

We only have information about six out of the 14 children: Leib, Leya, Hana, Joseph, Vladimir and Genia. Leib, Leya and Hana were born in Khodorkov in the 1880s. In 1903 the three of them moved to the US. Joseph was killed by Ukrainian farmers in 1924. He was a red commissar, and the farmers were against the Soviet power. Genia was born in Khodorkov at the end of 1900. She got married sometime after 1917 and lived in Nikopol. During the war she was in evacuation in Middle Asia. She returned to Kiev after the war. She had two children. She moved to Germany in the early 1990s and died there shortly afterwards.

My husband's father Vladimir Gomberg was born in Khodorkov in 1901. My father-in-law didn't study, but he could read and write. He worked at the nail plant in Kiev from the middle of the 1920s.

My husband's mother, Dora Sobol, was born in Khodorkov, Zhytomir region in 1903. Her father, Jacob Sobol, was a fishmonger. There was a big market in Khodorkov. He used to purchase fish from local fishermen and from the surrounding villages. He was religious. He celebrated Sabbath and holidays and went to the synagogue on Saturdays. He died in Khodorkov in 1939. This is all the information I have about him. Mihlia, my mother-in-law's mother, was a housewife. She spoke Yiddish and could also speak a little Ukrainian. She wasn't fanatically religious. After her husband died, Mihlia moved to her daughter Dora in Kiev. She didn't observe Jewish traditions in Kiev, but once in a while she lit candles on holidays.

There were three children in the family: Abram, my husband's mother Dora and Moisey. Abram was born in Khodorkov in the late 1890s. In the 1930s he was director of the sawmill in Khodorkov. He, his wife Etia and their daughter Sarah perished in 1941 on the first days of the German invasion. His son Efim, born in 1923, was the only survivor in the family. He was recruited to the army in the first days of the war. He was a gun commander during the war and was awarded two orders and a few medals. He died in 1977. Moisey was born in Khodorkov in the middle of the 1900s. He was a professional military and had the rank of artillery major. He was married. He perished near the town of Slutsk in 1943.

My husband's mother, Dora, was born in Khodorkov in 1903. She had to help her mother about the house ever since she was a little girl. After the revolution of 1917 she went to secondary school. She studied for several years. She learned to count, read and write. In the early 1920s she moved to Kiev and went to work as a laborer at a nail factory. My husband's father also worked at this factory. They met and got married in 1927. They couldn't afford a wedding party. Their first baby, Joseph, was born in 1928.

In the late 1930s my husband's parents got new jobs; his father worked at the food department and his mother became a shop assistant at a food store near the Bessarabka market, in the very center of Kiev.

During the Soviet-Finnish war my husband's father was recruited to the army. He was severely wounded on his legs. He had to stay in hospital for a long time until his wounds healed; and walking remained difficult for him after that.

My husband was born in Kiev in 1934. His grandmother Mihlia, who had moved to Kiev by then, was looking after him. During the war his mother, grandmother and my Arnold were in evacuation in the village of Galkino, Cheliabinskaya region [2,500 km from Kiev]. My husband's father was released from military service. He couldn't run or walk properly. At the beginning the family was starving in evacuation. My husband's father couldn't find a job, and his mother didn't work either. They received 100 grams of bread each per day.

In 1943 my husband's father got a job at the Zagotskot office. [This is a government economic agency for the provision of meat.] He was responsible for the selection of cattle for slaughtering. As an award for good performance he was given a cow. His grandmother Mihlia was familiar with looking after livestock. She milked the cow, made butter and sour cream. She sold her dairy products at the market and bought bread and sugar. My husband went to school. There was no anti-Semitism at school. His friends were local boys and children from other evacuated families, many of which were Jewish.

Kiev was liberated in 1943. My husband and his family returned to Kiev. They settled down in a damp and dirty dwelling in the basement of a house. They cleaned it up and glassed the windows. There was one room and a hallway with a big stove in it.

My husband's mother went to work at the thermoelectric power plant. She was a laborer. Besides, his mother and grandmother made rolls and pies to sell them at the market and get some extra money to support the family. My husband's mother had a heart disease. It was very damp in the basement, and she got kidney problems. Her older son Joseph fell very ill and died in 1946. When she heard about it she fainted and hit her head on a jug. As a result, she was paralyzed. She lived for another year before she died.

My husband's father returned to Kiev in 1947. He returned some time after we had left for Kiev. He had to remain in Galkino longer because of his work.

My husband finished lower secondary school in 1951, went to work and attended an evening school to complete his secondary education. He didn't get along with his stepmother (his father remarried shortly after his wife died). She was mean and greedy. Her only merit was that she could cook well.

In 1953 my husband was recruited to the army; he was in the Air Force. His service term lasted two years. After he demobilized, he finished a car repair school and worked as a driver and a car mechanic at a car maintenance facility until retirement. We got married in 1959, and he moved into our apartment.

My husband's father was the manager of a vegetable storage facility. In 1951, at the height of the anti-Jewish campaign, he was summoned to a KGB office. He was asked about his work and colleagues. A few days later he was arrested. He was accused of theft from the storage facilities where he worked and was sentenced to 15 years in camp. Several of his colleagues were also arrested. His wife divorced him immediately after he was arrested.

He returned to Kiev in 1966. We weren't allowed to correspond with him all these years. Later he didn't talk about the years that he had spent in the camp. He wasn't allowed to live in a big city after his imprisonment, and we bribed a state officer to obtain a residence permit 12 for him. Shortly afterwards he married a very nice and smart Jewish woman. Her name was Rachel. Her husband and two sons perished during the war. She died in the early 1970s. My husband's father died in 1978. They were both buried in the Jewish cemetery in Kiev.

In 1960 my husband, I and my parents got a new apartment. In the same year our first son, Vadim, was born and in 1972 our second son, Valery.

Our children were not raised Jewish, but we didn't let them forget that they were Jews either. In 1960 my father's mother Reizl died. We continued to get together on Jewish holidays. We didn't know any prayers, but we always cooked a delicious dinner: beetroot soup, chicken and gefilte fish. We always had matzah at Pesach. We bought matzah at the synagogue in Podol. We went there in the dark, because we didn't want to be seen there. We were afraid of having problems if somebody reported us to the KGB office. People were persecuted at that time for demonstrating their religious convictions. We ate plain matzah or made small pancakes, fried eggs with matzah and cakes. We didn't follow the kashrut, and we didn't have religious books at home, but we never forgot about our Jewish identity.

We always followed the events in Israel. We bought my father a radio and gave it to a repairman to adjust it so that we could receive short waves to listen to Western stations. Western radio broadcasts were jammed most of the time, but we managed to put together what we could hear. In 1967, during the Six-Day-War 13 in Israel, we were almost glued to our radio to follow the events there.

In the 1970s many of our friends and relatives were moving to Israel and the US. We were also discussing to move to one of these countries, but my parents would have never accepted it. They were dedicated to their communist ideas and regarded departure as a betrayal of the Communist Party and its ideas. So we never advanced farther than discussing it.

In the early 1960s a book by Solzhenitsyn 14, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, was published - the only publication in the 1960s about the life of inmates of Stalinist camps. We read this book. We were realistic about the situation in our country and the true state of things.

Our sons studied at school. Vadim liked the humanities. After finishing school he entered the Construction Institute in Perm, but he quit after two years. He was recruited to the army and returned to Kiev after his term of service was over. He finished the Road Transport College and became a specialist in car repair-maintenance. He married a Jewish woman and they had two children. They are divorced now, and she lives in Cologne with the children. My son remarried. His second wife is also Jewish. She has a son from her first marriage. Vadim works as a manager in a company.

Valery's school wasn't a very good school. The teaching process left much to be desired. Valery didn't want to go to another school. He didn't want to leave his friends. He finished eight classes and went to trade school. He became a professional diver. Last year [2001] he married a Jewish girl, and in August 2002 they moved to Israel.

Every year on 9th May [Victory Day] my father and I went to the Monument of Glory, the Tomb of the Unknown Ukrainian Soldier [a memorial to unknown Ukrainian soldiers]. Every single time my father was in a hysterical state. It must have been about what he knew and remembered, but he never mentioned anything to us. He never revealed this mystery, and we never found out whom he cried for and why he was afraid to tell us. My father died in 1986. His death was a terrible blow to me.

Life began to change in the 1990s. I quit my job, because I was earning very little there, and got a new job at the Podolianka private cosmetics company as a sales planner. This was my friend's husband's company, and this friend of mine recommended me to the management of the company. My husband opened a small car repair shop.

In 1990 my mother died. In 1995 we were thinking of going to the US, but we couldn't leave my husband's relative, Sonia, the wife of my husband's uncle Moisey, who had perished at the front. She didn't want to go with us. She is old and alone, and she needs to be looked after.

We have a visa for Germany and we plan to move there before 2003. My older son and his wife will be going with us. We decided to go to Germany, because my husband speaks fluent Yiddish and can understand German very well. We wouldn't be able to learn Hebrew. Besides, he had two heart attacks, and he can't stand the heat; it's too hot there. We can't stay in Ukraine either. My husband closed his shop due to his condition and I am a pensioner: We receive $50 USD pension between the two of us. We can't make ends meet with so little money. Besides, my husband needs a heart surgery. It costs $3,000 USD in Ukraine. We don't have such big amounts of money. These are the reasons why we decided to move to another country. Germany accepts Jews now. Many of our friends have moved there already. They receive welfare and free medical assistance and reside in comfortable apartments.

We are glad that Jewish life has been restored in Ukraine. We don't need to hide our Jewish identity now. We attend Jewish concerts and performances. Hesed supports us, providing packaged food and medications.

We celebrate Jewish holidays. We don't go to the synagogue, but we get together with friends at Pesach and Rosh Hashanah. We make traditional Jewish food on holidays: gefilte fish and beetroot soup with matzah - the same dishes my grandmother and mother used to make. Our children don't observe any Jewish traditions, but they always visit us on Jewish holidays.