Mimi-Matilda Petkova

Sofia

Bulgaria

Interviewer: Patricia Nikolova

Date of interview: August 2003

Mimi-Matilda Buko Petkova creates the impression of a strong and fighting woman, accustomed to defending her position to the end and able to survive all circumstances and changes. She is motivated by moral imperatives like: honesty, justice, existential freedom, social equality and social solidarity. But she believes in them only when she sees them realized in practice. She is tolerant and believes in values such as liberalism, democracy and respect.

I was born in the most beautiful town in Bulgaria, the capital of the Second Bulgarian Kingdom - Vidin, which was once named Bdin, back in the 12th century. The Second Bulgarian Kingdom was declared after the rebellion of the boyars Asen and Petar in 1186. This rebellion overthrew the power of Byzantium over the Bulgarians. The new territory of the Bulgarian state was between the Danube River, the Balkan Mountains and the Black Sea. The capital was the town of Tarnovo. Petar was declared king, and later on Asen too. If one stands exactly there, at the curve of the Danube, one can see Calafat [Romanian town] across the river. And the lights of Calafat are the lights of life: at first they come wide, then the Danube shrinks them, and then they fade away in one ray, for good. This memory of mine is unforgettable.

My ancestors came from Spain. They were called Bizanti. They were banished by the queen [see Expulsion of the Jews from Spain] 1 and passed through Italy. My ancestors spent some time in Toledo, where they were known as the Bizanti family, but when they passed through Piza, they renamed themselves Pizanti. Then they left for Turkey. Some of them stayed in Odrin and the others went to Bulgaria. [The contemporary Bulgarian State came into existence as late as 1878. Her ancestors settled in the Eastern Balkans, a part of the Ottoman Empire that became Bulgaria in the 19th century.]

The father of my great-grandfather was called David. I don't know anything else about him. His son Saltiel was my great-grandfather. He died as a volunteer in the fighting at Shipka Mount [see Liberation of Bulgaria] 2. My grandfather had three sons. One of them, Judas, was the father of Haim Pizanti, who was a famous personality in Bulgaria - founder of the communist party in the Vidin region and friend of Dimitar Blagoev 3. He was married to Sultana, who along with Vela Blagoeva, the wife of Dimitar Blagoev, was in the leadership of the women's organization in Vidin. In 1923 Haim Pizanti, his wife and three kids immigrated to Russia. There he was sent to Siberia, where he died during the repressions. His daughter, Renata returned to Bulgaria. Here she married the famous economist Jacques Natan. They also had three children: Dimi, Valeri and Tania. The first two have already passed away. At the moment the only heir to the Pizanti family is Tania Paunovska. Her son Vladimir Paunovski worked as an editor with the Sofia Jewish organization Shalom 4. Now he is the director of the museum at the Sofia synagogue.

Saltiel's second son was David, named after my great-grandfather. He had five sons from his wife Sarah. They were: Buko, Saltiel, Leon, Alfred and Sason. Their children were the parents of Jacques and David Pizanti who own the company of ladies' wear 'Pizanti' in France.

My great-grandfather Saltiel's third son was Isaak - my grandfather. He was married to Mazal Mashiah. He died in the Balkan War in 1913 [see First Balkan War] 5. They had two sons and two daughters. My grandfather was very religious. He was a tailor.

My father's name was Buko Isak Pizanti, but he preferred to be called Saltiel. He was born in Vidin on 20th December 1897. After I got married and moved to Sofia, he came to live with us. He was a very strict, but fair man. He never broke his word. He was not a complete atheist, because he kept my grandfather's tallit as a relic, as well as his kippah. When he went to the synagogue, he would put on his tallit and kippah at home. He seldom went to the synagogue though.

His siblings in their order of birth were: Liya, Israel and Sarah. When Liya was 16 years old, she got onto a carriage in Vidin, which turned over and... that was it. So only three of them remained.

My grandmother was a widow and supported her children by working in other people's houses. They were very poor. My father bought corn from the villagers and gave them some of the money in advance from a company, whose owner was Sason Pinkas. When the crop was ready, they transported it to Sofia and he paid them the rest of the money. After 9th September 1944 6 my father was employed in the trade business. He died of asthma on 16th March 1970. This is an illness he got while he was a common worker - his job was to turn the ears of corn over so that they would get damp before they were loaded onto the barge.

In 1918 my father fought as a volunteer in World War I. He had a medal of valor despite his death sentence. My father was a volunteer in the 6th infantry division [of the Bulgarian Army] during World War I. He was sentenced to death for organizing a mutiny. His sentence was N1009, issued on 12th April 1918.

Before he married my mother in 1920 my father went from Vidin to Sofia on foot and with no money to listen to a speech by Lev Trotsky 7. He was a member of the Komsomol 8. I remember my grandmother telling us how she boiled him three eggs for his journey. He ate them and sometimes the villagers he met on his way gave him something to eat too. And since he was afraid that he would tear his shoes, he took them off, flung them on his shoulder and walked barefoot. When he reached the Iskar River, he washed his feet, put his socks and shoes on and walked the remaining 10 kilometers to Sofia. Later the people there bought him a ticket for his journey home. So, he was quite wild. He married in 1920. Three years later he took part in the events of 1923 9.

He was imprisoned, because he had organized a mutiny. He was court- martialed. He was imprisoned in a barge together with his accomplices with the aim to sink it in the Danube near Vidin. But the international community managed to save them. In the end, in 1925 he was sent to prison, although he had nothing to do with the terrorist act. [Editor's note: the interviewee is referring to the bombing of the Sveta Nedelia Church] 10

My father's trial was very frightening. He had a death sentence. I wasn't allowed at the trial, because I was young, but my mother and my sister Liza went there. My mother was deaf. When Liza returned, she cried all the time. My father was beaten a lot, they hanged him with his feet upwards for 24 hours beating him on the heels. When my father was in prison, whatever we ate, my mother always divided it into five parts. She gave him his part when she went to see him every Friday. I also went to visit him: we had to wait in line before we were allowed to go in.

In prison my father made us shoes out of little laths nailed with tapes - instead of soles. My mother would knit some straps on them. I went to the front, wearing such shoes, trudging through the mud with them. They gave me some nice clothes only after the first fights.

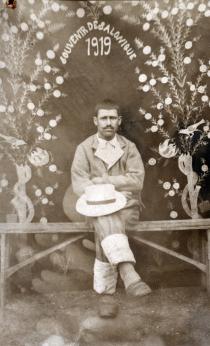

I know many of my father's adventures. He went to fight for Bulgaria as a volunteer. But when Bulgaria lost in World War I - we were on the side of the Germans [see Bulgaria in World War I] 11. The then Communist Party ordered them to abandon their positions. He headed the mutiny, which was against this order. When he was sent to solitary confinement to wait for the trial, his friends brought him food and water secretly. His guards gave it to him, probably because they saw that he was right. When he was a prisoner of war in 1919 in Thessaloniki, he got malaria and the English treated him in a wonderful way. They gave him all the necessary medications. He told me about the barge in 1923, the people in the hold: they had no water, not enough air... By the way, in 1923 the police arrested my father at home while he was asleep. My mother got so scared that both her eardrums burst. My mother remained deaf for the rest of her life.

My father went to the synagogue, but he was an atheist. My mother was very strict on rituals. Everyone at home spoke Ladino, but my parents talked to each other in Turkish when they wanted to say something that the children shouldn't understand. They knew Turkish perfectly. Naturally, they knew Bulgarian as well.

The best synagogue in Bulgaria was in Vidin. It was very acoustic. I went with my mother on the balcony. She often went there. When Sabbath di Noche [Sabbath Eve] came, we always went there. I remember the paschal sweets, which the chazzan Meshulam gave to us. We had a shochet and he was the father of my uncle. There were a number of rabbis. I carried the chickens to be slaughtered at the synagogue. We didn't do that very often because we had no money. When I was 13 years old, my father gave me a bracelet for my bat mitzvah, telling me, 'From now on you are a woman.' I still keep it.

My father read more than my mother. He liked various Soviet books - from 'Dead Siberia Fields' to books devoted to Lev Trotsky. My father also loved singing. When we gathered with my father's sister and her husband at home or with my mother's brother and his wife, he always sang Ladino songs: 'Una morte union', '?tra muher nokero', 'Una chica corazon'.

My mother's name was Sarah Avram Pizanti, nee Lidgi, but everyone called her Freda. She was born on 8th August 1895 in Vidin. And she died on 30th October 1985. Her mother died when she was giving birth to her last son. My mother didn't know her father, because she was seven years old when he died. So, I didn't know any maternal or paternal grandparents.

My mother was a diabetic. She was almost illiterate. During the Law for the Protection of the Nation 12, she worked as a housemaid for the rich Jews. I, as the youngest child, went with her, peeling onions, potatoes etc.

My mother observed all holidays, especially Yom Kippur. We gathered with her brother and my father's sister. They didn't eat because of the holiday and we, the children, stayed in the shupron [shed for coal and wood], where they gave us something to eat. One day, on the evening of Yom Kippur after the shofar played in the synagogue and the family gathered, my father came back from the synagogue with the words: 'Come on, I'm hungry...' My mother brought him a dish of stuffed peppers. And suddenly she cried out: 'Buko!' and she fainted. Everyone started to fuss around her. When she came to, she said: 'Look, what you have on your tie!' And on his tie under his chin he had a piece of spaghetti. My mother was horrified that he had eaten during the day. 'How could you do that, Buko!', she said.

My father was a firm communist whereas my mother wasn't a member of any party. She was always afraid for him. She would tell him in Ladino: 'You will eat us out of house and home and ruin our children.' The house, the family, the home - that was my mother. She sewed clothes on a sewing machine so we were always neatly dressed. We, the sisters, passed the clothes to each other. The coat, which I wore at my wedding, in fact, belonged to my sister.

My parents knew each other from early on, because they were neighbors. They dressed like the others. My mother told me that her brother bought her cheap high-heeled shoes. The other sisters wore slippers with heels. My mother was raised by her brother, who also raised his other brothers and sisters. The shoes she was talking about were a bit above the ankle, with laces. Once she cut them from top to the bottom with a knife and he made her sew them together again. Then she continued to wear them for quite some time. Uncle Yako, her brother, bought my mother her first nice pair of shoes when she got engaged. That made her very happy.

At home we most often celebrated Yom Kippur, Fruitas 13 and Pesach, of course. My mother made delicious dishes from matzah and other things. I remember some wonderful paschal sweets, which we received at the synagogue. Often Uncle Yakim came on Pesach and my father would tell him, 'Come on, mumble something!' He was the son of the shochet and started like this, mumbling under his nose: 'Mmmmmm, uuuuuuuuh,' and did not say one word!

I loved Fruitas very much - the holiday, at which tanti [aunt] Sarah, my father's sister, filled some silk bags with fruits for us, because we had no money. It was my favorite holiday. She put dates, oranges, tangerines, nuts and plums in the bags. She would also put one lev in each so that we, the children, would have some money for the cinema or something else.

My mother loved telling a story, with which she wanted to warn us not to be too greedy and to make do with what we had: At midnight on Fruitas the trees kiss each other and God fulfils the wishes of all the people. At that moment an elderly woman stood at the window of her house, which was bolted with vertical bars. She managed to squeeze her head through the bars. When the trees started kissing, instead of saying 'Da mi grande cabizera!' ['God, give me wealth'], she said: 'Da mi grande cabeza!' ['Give me a big head'] And God granted her wish. She stayed with her head protruding outside for a whole year, and when the next Fruitas came, she said: 'God, please, I don't want anything - give me my head back!' And so she was back to normal. The moral of the tale according to my mother was: 'Do not want a big 'cabizera' - literally a pillow, and symbolically a 'state'. Better to want something small and God will fulfill it, otherwise he will punish you. I told this story to my children and my grandchildren. One should be satisfied with what one has and fight for as much as his or her strength allows.

My sister Veneta was born on 6th August 1925. Veneta finished junior high school. She was a seamstress. She married Haim Alhalel. Veneta always had a very sick heart. I remember that I waited for a whole night and half a day for her daughter Sonya to be born. Then I took her from the maternity home and brought her home as if she were a child of mine. Veneta died in Sofia from cardiovascular insufficiency on 24th February 1993.

Liza, my other sister, was born on 22nd January 1922. She finished her secondary education in Vidin high school. She had a college education and was a pharmacist. She married Tsvetan Penev. Liza has two sons, one of them is Fredi - named after my mother, and the other - Valentin. Liza died in 1995 after she had fallen down and broken her leg.

Both my sisters spoke Ladino. Liza knew Italian. They also lived in Vidin. When Liza married, she went to live in Byala Slatina and then I also went there to study in the technical college. I lived at her place for a while. But when I married too, everyone came to Sofia: my parents, Liza, Tsvetan, Veneta and Haim.

Once Veneta and I found the notebook in which my father wrote down what amount of money he had given to whom. Usually there was a fair on 28th August in Vidin. All children went there and their parents bought them confetti. So, we decided to make ourselves confetti from this notebook. That was such a disaster: the money of the owner of our house got completely mixed up. I still remember my father taking the notarial act of the house and giving it to the owner - if he didn't manage to collect the corn, the owner was free to sell our house. But the villagers were very honest and everyone brought him the corn. At the end of August, beginning of September my father came home with a big paper, in which sausages and warm bread were wrapped. He also brought back the notarial act. This happened in 1938-39.

At that time Jews were mostly merchants. For example, my father's cousins - the five sons of David - worked in Bourgas then, making contracts with companies importing Citrus fruits by sea. The market in Vidin took place every Friday. It was a colorful, typical village market. The women sat on the ground with their baskets and kerchiefs, because there were no stalls. You passed and they would shout at you: 'Come here, come there...' I loved it when my mother was walking around the market and she walked around three times so that she would be able to get the cheapest products. When my father worked and wasn't in prison, he often brought from the market a donkey cart with watermelons and melons. We, the three sisters, would line up with my father at the front, and we passed them to each other... If someone missed a fruit and dropped it, we ate it. I also remember that there were times when we couldn't afford to go to the market.

Before I was born, my father lived with my mother in the village of Gradets, Vidin region. I was born there. We had some very good friends - Uncle Lozano and Uncle Rusko. When the Law for the Protection of the Nation was passed, they brought us pumpkins, maize, flour and other stuff. The Jews could go to the market, but they could shop only with special talons, called food coupons, and only at specific times of the day.

Our house had two entrances. We paid for it in installments. At first the landlords lived with us. We lived in one of the rooms and my father paid them every month. We didn't have a garden. There was a cobblestone yard with very clean tiles. We washed them with a hose. We also had electricity. There were a number of extensions - a hen-house, a toilet and ? shupron. When my father paid the last installment, Uncle Stamen, the landlord, slaughtered a hen and opened a bottle of wine. We had a big mulberry tree in the yard; they sat under its shade, drank and sang... My father sang very well: 'Un amorte...un amor...' So the house became ours. This also happened in 1938-39.

We didn't have servants. As I said, my mother went to cook in other people's houses and I helped her. In 1941 when the Law for Protection of the Nation was passed a man called Ivan the Beast, the police chief, came and banished us from the house. We went to live under the hen-house and the shupron. We slept on the floor. All our belongings, the beds, the dishes, etc. remained with the Beast. At that time my father was in prison. Ivan the Beast returned from the Aegean region, when the Aegean Jews were all shipped to Majdanek 14. [Jews from the Bulgarian occupied Yugoslav and Greek lands, Macedonia and Aegean Thrace, were deported to Nazi death camps.] From there he brought home so many clothes and other stuff that his wife didn't know what to do with it all.

I didn't go to kindergarten; my mother took care of me. I studied in a Bulgarian secular school. I loved two subjects: history and Bulgarian language and literature, because history was related to my ancestry and I simply love Bulgarian poems. I wasn't sent to a Jewish school, because my father was an atheist and I had already begun my studies in the Bulgarian elementary school in the village of Gradets, where I was born. My favorite teacher was the one who taught me to write. His name was Tsankov; I remember him from the first grade. Our teacher from high school, who taught us Russian and French, from the forth until the eighth grade was Russian. Her family name was Belcheva, nee Galkina. She was a very cordial and charming woman. When she was talking, we couldn't take our eyes off her. She was the reason I loved Pushkin 15. I even named my daughter Tatyana after the female protagonist in 'Eugene Onegin'.

As I mention earlier, I didn't study in a Jewish school, but the Ivrit of the Jewish school, when he met me on the street, would shout, 'Pizantika, you must come to my class!' However, my parents had decided otherwise.

Uncle Stamen, the owner of the house, lived in the yard of our house. He was very tolerant. At the back of the yard on the other side, our neighbors were Jews. Haim Alhalel lived there. He fell in love with my sister Veneta and they later married. They had a big pear tree and when he climbed it to pick them, the pears would always fall in our yard and I couldn't explain why.

Aunt Ayshe, a Turkish woman, lived on the opposite side. She was also very nice. But two houses away from us, there were fascists, Branniks 16, Legionaries [see Bulgarian Legions] 17. They hurled stones at our house, shouting: 'Jews, leave our country!' This happened when the Law for the Protection of the Nation was passed, at the beginning of the 1940s.

I had many friends as a child. We lived in the Jewish neighborhood. At that time the town was small: around 19,000 people lived there, 8,000 of who were Jews. Rozanov was chairman of the Jewish organization. Later I was a member of a Jewish UYW 18 group. Our leader was the now well-known professor Avram Pinkas, a renowned surgeon. Our group also included Marsel Varsano, Leon Pinkas and Beka Aladgem. He was very pleased with me. I took part in all track tracing games, etc. In Hashomer Hatzair 19 I learned for the first time about Keren Kayemet Leisrael 20; I also learned the song 'Pumpkin, pumpkin' and other stuff. I didn't have much free time, because I often went to work with my mother. We cleaned and cooked in other people's houses.

Despite all the friends I had in Vidin and all the love I got from the Bulgarians - and there were also Armenians and Turks among my friends - I also remember a lot of hatred. I will not forget how when the Law for the Protection of the Nation was passed, the headmaster made us line up in front of the school. The high schools then were divided into girls' and boys' ones. In March 1941 we were already wearing yellow stars. Mr. Cholakov, the headmaster of the girls' high school, said, 'Mimi Pizanti, Beka Arie, Fifi Kohen and the others - two steps ahead. You are not wanted in our school from now on.' I left. The high school was quite far from home - I mentioned that we were close to the Jewish school - and I cried all the way home. My father wasn't in prison yet and he said, 'You don't need it. The socialist times will come, we will make our own schools, you will go to study in Russia, don't cry...' I will never forget that.

I was six years old when I first got on a train. My uncle in Sofia adopted me; he came to Vidin and took me in 1931. In accordance with the tradition, it was normal in a Jewish kin, that a family who had more children, gave one of them up for adoption to a childless brother or sister. That's what they did with me. Since I was the youngest, my father gave me to the family of his brother and his childless wife to look after me. I lived nine years with my uncle, until 1939. That is, until the Law for the Protection of the Nation was passed and Izie was born [nine years after Mimi's adoption the family had their own child, Izie]. Then my mother took me back.

Before the Law for the Protection of the Nation, once a year my father and I went to a fair. There we bought kebapcheta [grilled meatballs], which were served in big clay dishes and were delicious.

I remember the military parades and the holidays during which our school went to manifestations. 24th May 21 was a very nice holiday. We took part in the manifestations. All students were taken to church and we, the Jews, had to wait outside. Apart from me, I remember that Becca Arie, Fifi Koen and Viko - I don't remember his family name - also studied in that school. So, we played in the yard of the Bulgarian church.

I spent only one of my holidays at Moshava, a camp of Hashomer Hatzair. It was in present-day Velingrad. I remember that I ate very little. And my mother told me: 'If you eat French beans the whole summer, you will go to Moshava, if you don't eat, you won't go.' So, I grew to like French beans. I remember that my grandfather's brother kir David ['kir' means 'mister' in Turkish and it was also used in Bulgarian at the beginning of the century], who had five sons, had 50 levs in coins with the image of King Boris III on them. He went to my mother and said, 'Take these 50 levs and pay for Moshava. When her father comes out of prison, he will give it back to me.' Of course, my father didn't return it, but the important thing is that I went to Moshava and I liked it. That was my only vacation. During my other vacations I stayed at home and worked. There was no other way. I worked in the 'Arda' cigarette factory and in vegetable gardens for a guy named Tarzan. I still remember him standing at the beginning of a vegetable row and yelling 'Come oooon!' Even now when I'm doing something and someone stands behind my back, I start to shiver all over. I was a child at that time, after all.

Victoria Ilkova was a classmate of mine, a Wallachian [Romanian minority, living in various parts of Bulgaria, among them Vidin, by the Danube]. During the Law for the Protection of the Nation, when we were expelled from school, her brother was a political prisoner and in one cell with my father in Vidin prison. She lived in the Wallachian quarter of the town - Kum Bair, which was quite far from our home. But she came to our house, carrying lots of products wrapped in a canvas and hidden between her trousers and her panties. She brought us flour and meat and thus helped us. I will never forget her kindness. We survived because the Bulgarians were nice and tolerant with us [and so were the Wallachians, the Romanians].

After 9th September 1944 the police chief Ivan the Beast was arrested, because he beat political prisoners in the army. His wife Penka took their luggage and went to the village of his mother. We were very poor, so there was nothing they could take from us. But we had a red dress that I will never forget. At the port we were waiting to be taken to the barges and my mother had sewn for us bags for our most precious things. They told us, 'Leave you luggage and go', because they thought there was gold in it. Later I saw Rumyana, the daughter of the police chief in our red dress. And it was the only nice dress at home and my sister Veneta and I had taken turns to wear it. For the fifth anniversary of our marriage my husband bought me red cloth so I could have a red dress sewed for myself.

Speaking about the tolerance of our neighbors: we had a big mulberry tree in the yard. I was a very wild child and because of that my mother beat me up with the tongs occasionally. Once she chased me - I don't remember why - and I quickly climbed up the tree. But I slipped and my head got stuck between two branches. I couldn't free myself. At that time Uncle Stamen was painting his house and he had a tall ladder for masonry. They put my feet on it and tried to untangle me from the branches, but with no success. Haim's son-in-law came. He was a tinsmith, brought a tin, climbed up the ladder and placed it gently in front of my head. So, they were able to cut the branch. When they brought me down. I couldn't sleep for one week because of the horror I had experienced. One cannot forget such an experience; I was a very wild child.

The first anti-Semitic incidents were very frightening. They happened in high school and in other places and especially once we had to wear the stars, and they put a board on our door, which read 'A house of a person of Jewish origin' at the beginning of the 1940s. Before my father went to prison, he had put vertical wooden laths on the windows, like blinds, so that the glass wouldn't break when they hurled stones at the house. We sat in the dark most of the time, because the anti-Semites passed frequently near our house. Naturally, they were all members of pro-Nazi youth organizations such as the 'Branniks', 'Ratniks' 22 and 'Legionaries'. They were very similar to the Hitler Youth [Hitlerjugend] 23 in Germany. These incidents happened on Tsar Simeon Street. Such things cannot be forgotten.

I remember the anti-Semitic attitude of some of my classmates. In high school our class decided that no one should wear badges, otherwise they would be 'fined'. And when the Law for the Protection of the Nation was passed, we put on our yellow stars. When I went to school the first day, Rumyana, who was the chairperson of the class and the daughter of the police officer of our living estate, shouted, 'Take that off or we will fine you!' I told her, 'I cannot take that off, or your father will imprison me.' Her aim was to insult me. She knew that we, the Jews, wore 'Magen David' by force, but she pretended that she didn't know that, calling it merely a 'decoration'. However, I also had some good friends, for example, Kanna Semkova, Nadezhda Mladenova, Ilinka and Yanka with whom I shared a desk. When that happened, they told me, 'Don't pay any attention to her, don't cry, she is simple-minded'. But I could feel the humiliation. For example, I had to go to a supplementary examination in gymnastics in the former fifth grade, present-day eighth grade, because my teacher was head of the Legionary organization and a Brannik in Vidin. This Mrs. Stefka Ivanova made me dance Paydushko 'horo' [folklore ring dance]. I wasn't able to dance it properly and I had to go to a supplementary examination. I sat for it in spring, failed and had to sit for it again in fall. So, I just about managed to avoid repeating the grade. When 9th September 1944 came, I went to the front, so I didn't go to that supplementary exam, but I had the gymnastics class recognized as passed.

At the end of April, beginning of May the same year - my father was already in prison - a representative of the police came: Milushev from State Security. He handed me an order. One of us had to go to work in the State Hospital in Vidin where there was a ward especially for Germans, because the ferry to Calafat had already been built. The wounded soldiers from the Eastern front were transported to Vidin hospital, bandaged, and those who could handle it were transported to Germany by plane. Those in serious condition remained in the hospital.

At that time I was 14 and a half years old. Dad was in prison and my mother decided that from the three sisters it was safest for me to go through this period. So, she said to that State Security representative that I would go. They put a notice under the yellow star with my name and saying that I had the right to go out every morning between 6 to 6.30 am, to pass along Tsar Simeon Street to the State Hospital and return the same way by 5-5.30 pm in the evening. According to the Law for the Protection of the Nation all Jews were allowed to go out only at certain hours.

I will never forget the horror I experienced in the hospital. From 1941 until 1944 I worked in two rooms as a hospital attendant - I cleaned the urinals, washed and changed the clothes of the patients, cleaned the rooms... there were 16 Germans! All the time they pinched me and insulted me, saying 'Jude kaput!', etc. Since there was no food at home, I collected the leftovers and took them home to support the family. Maybe that's the reason why I found a partner quite late - in 1948. After all that I felt terrible. You also have to bear in mind that my great-grandfather died as a volunteer on Shipka Mount and my grandfather in the Balkan War [First Balkan War], my father fought in World War I and I myself fought in World War II... In January 1943 I stood at the port in Vidin waiting to be sent to Majdanek concentration camp. But the bishop came, put his hand on my head and told me, 'Don't worry child, you will not go.' He consoled me in this way.

When we had to wear the yellow stars in 1941, we weren't allowed to leave the neighborhood - Kale Husan. We could go to the neighborhood shops, but only during specific hours. Our homes were houses with yards, and between them there were little doors, the so-called 'kapidzhik', through which one could pass into the neighboring yard. We, the children, often roamed the whole neighborhood and then returned to our homes without going out into the street: from one yard into another, from one yard into another. If we saw some fascists or policemen coming, the little doors solved the problem right away. In this way we saved some people who were about to be arrested. For example, the well-known anti-fascist Asen Balkanski, commander of a Yugoslav brigade, hid in our basement for quite some time. In the end, he was transferred into a wagon and only later did we find out that on the border with Yugoslavia, in the town of Kula, they caught him and shot him down as a political prisoner...

I went to the front when I was 17 years and three days old. The Germans withdrew on 5th September. The partisan squad climbed down the mountains on 8th September, smashed the prison gates and so my father was freed. It was such a happy moment, we all gathered on the square, all people regardless which party they belonged to. It was 10th September 1944. Then we heard that the Germans were coming back. They had forgotten to blow up the ferry over the Danube, to Calafat. And the Soviet army was on the Danube border. The commander of the partisan squad - Ivan Vitkov Bakov summoned us, 'We have to organize a volunteers' team until the Soviet armies come and the situation in the regiments is normal again. You have to stop the Germans!' We had the third Drinski regiment, but they did not go then.

So on 10th September wearing these shoes sewn by my father and a summer dress I got on the truck. My sister Veneta caught up with me and said, 'Our mother is crying, they will kill you, get off, father is not in prison any more, get off!' I was very wild. I said to her, 'I will be killed, not her, why is mother crying?' So, I left. In the village of Voynitsa we were stopped, because the Germans had already passed through the border town of Kula and headed for Vidin. The village of Voynitsa is six kilometers from Vidin. We were given weapons, although we were not instructed how to use them. I carried a manihera gun, although I saw a gun for the first time. They showed us how to shoot.

At one point two motorcycles with two people on each one - German scouts - overtook us. Our boys aimed at them, killed one of them, the motorcycle fell, the other ran away and the others escaped and returned within an hour. We shot at the tanks, but the bullets rebounded. Kostya, a Soviet soldier, who had been a captive of the Germans and had come to welcome the Soviet army, grabbed two grenades, put two more on his belt, shouted, 'For the fatherland' and threw himself at the first tank. He pulled out their plugs and blew the tank away. The other tank withdrew. So Kostya died, at the threshold of freedom. He was the first Russian soldier who died on Bulgarian land. That is why there is a notice in Voynitsa: 'The Russian soldier Kostya died here.'

I have a big sin with regard to my parents: not only did I run away from them to go to the front, but also I didn't write them a single line. In the fights in Yugoslavia a Jewish girl died. She was from Silistra. Her name was Solchi. The kulaks 24 had killed her husband and son. I was 17 years old then; she was 25, that is, eight years older than me. They called her 'the Jewish girl'. They called me '6 by 35' because I was small and I carried a lady's gun [a smaller gun]. A friend of my father went to Vidin and my father asked him about me. 'Buko, they killed a Jewish girl, but I don't know her name...' Then they recited the Kaddish for me at the synagogue, believing that I was dead.

I returned at the beginning of June, because I was with the occupation soldiers. It was Sunday and my father was at home. He told me, 'How could you do that? Why didn't you write us a single line...' Then, for the first and last time, I saw tears in his eyes. And my mother told me, 'Loca! [Ladino for 'crazy'] And we gave our last oil to the synagogue...'

There was a coupon system at that time. The first thing I did when I came back was to apply to take my exams. Two teachers prepared me: one in maths - her name was Bronzova - and one in literature - I don't remember her name. I didn't know much. I was allowed to study in the eighth grade, which is the present-day twelfth grade. It was very hard for me and yet, I managed to complete my secondary education. Then I worked in the District Committee of the UYW since my father had no money to support me; he supported my older sister at that time, in accordance with the tradition. Then she married in the town of Byala Slatina and I went to study in the secondary technical school there. I met my husband Tsvetan Georgiev Petkov there. We were in the same youth UYW leadership. Then we both were members of a brigade 25 in Pernik. Later he went to a school for officers in reserve in Sofia and I went to work in the Agriculture Ministry in Sofia where we married.

The war gave me many things. I spent 46 days and nights on the battlefield. First, it helped me reconsider my life. Secondly, it made me firmer: more honest, more sincere and stronger. It could sound vain, but it made me the only Jew in Bulgaria with two medals of valor. So, I also defended the Jewish lobby in that war. Not only me -there were 2,848 Jews, 48 of them died, 240 of them were women.

Naturally, after the Law for the Protection of the Nation was abolished, we had more freedom. We had only our house, and everything in it was broken. At that time I wasn't in Vidin; just after the end of the Law for the Protection of the Nation I went to the front. My sister continued to study, the other one continued to work, and my father also worked.

I didn't emigrate, because we fought for Bulgaria. When I was at a symposium of Jewish medal holders 50 years after the end of World War II and Vivian, a medal holder from France, was called, the whole audience was clapping and shouting, 'Vi-vi-an! Vi-vi-an!' When Mimi Pizanti from Bulgaria was called, nobody clapped, but everyone stood up. For ten minutes they chanted: 'Bulgaria! Bulgaria!' [Mimi was associated with Bulgaria, which had saved the Jews within its territory.] That's why, my dear Bulgaria, you are my fatherland. It's true that Israel is the fatherland of my ancestors. Israel is the cradle of the Jewish people, but I was born here, my sisters and parents died here, my ancestors died here and my end will also be here.

My husband was born on 3rd March 1927 in the village of Dobrolevo, Vratsa region. My mother-in-law was a priest's daughter. Imagine a village in which one mother-in-law has four daughters and only one son, and the daughter-in-law - a Jew. In 1950 that was quite something. 'She is Uvreika, uvreika...' ['Jewish woman' in the local dialect; in proper Bulgarian it is 'evreika'] said the villagers. Only when my son was born and I named him Georgi after my father-in-law, he crushed some grape, treated the people on the street and said, 'She might be a Jew, but she gave my name to her son...'

My daughter Tatyana was born on 27th October 1951. She graduated from high school with a gold medal [awarded to excellent students] and from the textile machinery course at the Machine Electrical and Technical Institute. Then she specialized in industry design and now she is associate professor at the New Bulgarian University, teaching 'fashion'. Tatyana married Veselin Penchev, an engineer and forester. They have a son, Stephan, who will have his bar mitzvah this year.

My son Georgi was born on 27th September 1956. He graduated from the Russian high school and has a university degree in nuclear power engineering. He is unemployed. He is married to Ira, who is from Plovdiv. Ira was born on 24th October 1956. She is a historian and works in the Bulgarian State Archive. Their son is the first-born heir of the family - Ognyan Georgiev. He graduated from the French high school and has a university diploma in Economics of Military Industry. At the moment he works with the Europe TV station as an editor and news reporter. My son's second son, Valeri Georgiev, is six years younger and was born on 11th November 1986. Now he is a student in the 10th grade of the French high school. His character resembles mine; he is very disobedient and wild.

When my mother-in-law was visiting, we observed all Bulgarian holidays with no exception. When my mother was visiting, we observed all Jewish holidays. There were a lot of national holidays at that time - we observed 9th September 1944, 7th November [October Revolution Day] 26, 24th May, etc. But my children know that when the mother is a Jew, the children are Jews too. So, with Tatyana or Stefan, the Jewish strain in our family will be over. Stefan went to Sunday school at Shalom; Ognyan went to a Jewish youth camp in Szarvas in Hungary. At home we observe Fruitas, Pesach, Sukkot and Yom Kippur. We all eat matzah with no exception.

I was the founder of the section 'Disabled People' at Shalom along with the late Dr. Avramova and the late Lazar Sarchi.

In 1948 my uncle, who adopted me when I was nine months old, invited me to go to Israel with him, but my father didn't allow me to. My uncle's wife was killed in Bulgaria and there he married for a second time, a woman who had a son and a daughter. Once, my uncle sent me a letter asking me whether I could sell his apartment here. This was absolutely impossible; it was 1950. I had some very close friends from the war front. I promised him that I would do it if he sent me a warrant of attorney, because you cannot sell a property without having a document granting you that right. And I received a letter from his son-in-law, Moshon, saying that I was very cunning and wanted to steal my uncle's apartment. It said that the communists had already stolen everything the Jews had and since I was a communist and had fought at the front I should be able to sell the apartment without my uncle sending me any documents. And that if I had such good connections to sell the apartment, why hadn't I arranged to have a permit to come and visit Israel? The letter insulted me so much that in the period February-April I sold my uncle's apartment without any warrant of attorney and without keeping a single coin for myself; all the money was directly transferred to my uncle's account.

I also sold the house of Uncle Strel's nephew in Rousse. He had a workshop for shirts - 'Elen-Serdika'. His wife Berta was a rich woman, with a diploma in obstetrics. She was killed in her own home in 1947 - the day when Tito 27 visited Bulgaria. The reason was not an anti-Semitic but a political one. Berta was a famous communist. Selling his house was very hard but I managed to do it in 1959. I was so insulted by Moshon that on 8th March 1960 I applied for a visit to Israel. I decided that I should show them that I can go there. But the authorities refused to give me a foreign passport. They wouldn't let people go to Israel if they didn't have next-of-kin relatives there - mother, father, sisters or brothers.

The head of the passport department was General Georgi Stoyanov - a friend of mine from the war front, and yet he didn't let me go. Ten months of waiting passed and on 8th March 1960 I went to the hairdresser's, put on my new clothes, took my two medals of valor and the party ID and I went to the Department of the Interior. I went to the waiting room and two strong young boys asked me 'What do you want, comrade?' I said, 'I came to be greeted by the minister on the occasion of 8th March'. [International Women's Day] 'But you cannot enter, who are you?' While we were arguing, the door opened, the minister came out and asked, 'What's going on?' I said, 'I came so that you would greet me on the occasion of 8th March', and I entered. And he said, 'Do you have an appointment?' 'No, I don't have one, it's 8th March today'. And I remember him taking out a yellow daffodil from the vase and saying 'Here you are! Happy 8th March! Now, tell me, why are you really here?' And I told him everything. 'Why can't I go? I have a ten-year-old daughter here, a five-year-old son, a husband I love, my sisters and my parents. Their children are here - if I escape, they will suffer...' He watched me for some time and said, 'But where do you think you are?' I answered, 'In the office of comrade Solakov, Secretary of the Interior'. 'This is impossible,' said he. 'Why?' I asked him. 'Because, this isn't decided by the ministry, but by the Political Bureau.' I said, 'is that so? Here is my party ID, give it to the Political Bureau and tell them that if they don't believe me, I don't believe them either.' 'But you cannot do that, this is not the Central Committee...' And I said, 'Goodbye'.

So, I left the party ID there and left. March, April, May and June passed and in the middle of July General Stoyanov rang me one evening at home, 'Mimi! Come to my office tomorrow, alive or dead!' I thought that my husband and I would be fired and that my family life was over. I went and he told me, 'Here is you foreign passport, here is your visa, here is your party ID. This is not the way to return your party ID! Where do you think you are?' And I said, 'I'm in Bulgaria, I fought next to you and I think I can return that party ID.' So, in the fall of 1960 I went to Israel. Naturally I visited Israel as a Jew, not as a communist. However, I've always felt a communist, up until today.

I had many problems at work for being a Jew, but my name protected me. On 10th November 1989 28 I was already a pensioner; I retired in 1982. Before that I worked in 'Energoprojekt' [a state firm] as control specialist. I was also in charge of the party affairs; the party secretary was my boss, in the 'political prison' department. I had a colleague, who was filling in for me when I was absent, whose brothers immigrated to Brazil in 1939. So, he wasn't allowed to leave the country at all. In 1981 his eldest aunt died in Macedonia. He wanted to go there, but he wasn't allowed. So, I went to the personnel department and asked them who was in charge of Energoprojekt. They told me, 'State Security'. After calling a lot of my friends, I found out who was the person in charge there. I asked him, 'Why don't you let Mitsakov go? He is a very useful employee. He has a daughter and a mother, and Macedonia is close.' 'What will he do in Macedonia? He can't go, comrade!' 'And what do you think he will do?' 'He will persuade his brothers to come back...' 'How can you think that? They left in 1939, they already have families, work, children, grandchildren etc...' 'No, he can't go.' I told him, 'Listen, boy, here is my party ID. If Ivan Mitsakov doesn't come back, do what you like with my family and me!' They let him go. I warned him, 'If you don't come back, I will kill your daughter!' He came back, but on his way home his car radiator broke, and he stopped in a forest to repair it. When he finally passed the border, he stopped in the first village to call me. And he said, 'Mimi, I'm in Bulgaria, don't worry!'

And a second case: The best specialist in our department was Emil Kontev. He won a post in Algeria as a councilor to the minister, but the authorities sent a communist there, some incompetent man. I asked the head, 'Pesho, why?' 'But Emil's grandfather had a water-mill...', said he. 'Are you mad? He will build the image of Bulgaria, a smart man should go, so that he will present us positively!' So, they allowed him to go. When Emil Kontev came back, he asked me, 'What do you want me to give you as a gift for helping me spend six years there, having a great time?' I said, 'Give me something for my hands, not for my mouth.' He gave me a bread knife as a present and I still use it, remembering late Emil. Then they changed my job, because they said the non-members of the party had a bad influence on me.

I wrote a letter to Jan Videnov, who was Prime Minister at that time. It read: 'If you don't exclude Lyubomir Nachev from the party, I will return my party ID.' [Editor's note: Lyubomir Nachev: Secretary of the Interior in Videnov's cabinet, whom Mimi considered incompetent, moreover his name was associated with public scandals.] They didn't reply. After three months I sent my party ID to Yanaki Stoilov [Socialist Party member and activist] and wrote to them: 'I don't want to be a member of such a party.'

I was very insulted by Germany, because they don't think that those three years I worked for free in Vidin hospital as a child was slave labor. I received financial aid from Switzerland.

Glossary