Michaela Vidlakova

Prague

Czech Republic

Interviewer: Pavla Neuner

Date of interview: June 2005

Michaela Vidlakova is from Prague, where she was born in 1937. She grew up in a family that actively maintained Jewish traditions. Both of her parents had actively participated in the Czech Zionist movement 1 from the time they were young; Mrs. Vidlakova’s father, Jiri Lauscher, even helped found the Sarid kibbutz in Israel. He wanted to get married and move to Israel with his family. His plans were hatched however, by the arrival of Hitler. Mrs. Vidlakova tells of how her entire extended family was gradually deported, and finally she and her parents as well. Her description of her involuntary stay in Terezin 2, where as a child she was forced to endure over two years, gives a lifelike picture of life in the ghetto with all its happenstances that influence a person’s very survival. The activities of Mrs. Vidlakova’s parents bear valuable witness of the life of Czech Jews before the war, in Terezin, as well as during the postwar period. Her mother, Irma Lauscherova, was already a popular teacher before the war, and to this day many of Mrs. Vidlakova’s contemporaries remember her from when she was at the Jewish school in Jachymova Street in Prague. Irma Lauscherova didn’t stop teaching in Terezin either, despite it being strictly forbidden. Thanks to her work and courage, the children that survived Terezin were able after the war to continue in school and take material that was appropriate to their age; apparently many times their knowledge was even broader than that of children that didn’t have to interrupt their attendance of school due to their background. After the war, both of Mrs. Vidlakova’s parents worked for the new Israeli embassy in Prague. Her father was even the one left to close the embassy at the end of the 1960s, after Czechoslovakia severed diplomatic relations with Israel 3, and the embassy staff had to leave the country within the space of a few days 4. For long years, Jiri Lauscher also illegally supplied documentary material to the Beit Terezin Museum in Givat Chaym Ichud, Israel. Both of Mrs. Vidlakova’s parents were also among the first Czech Jews who were willing to travel to Germany and lecture on Jewry, Terezin and the Holocaust. In Bohemia they for a long time stood in for today’s Terezin Initiative 5, and acted as guides for individuals or groups traveling to Terezin, where at which time no museum yet existed. Michaela Vidlakova continued in this activity after them; from 1970 she also led a group of Jewish children with Mr. Artur Radvansky. They organized activities for the children, summer and winter camps, and spent weekends with them. As she herself said, they tried to provide a Scouting-Jewish education for them. Michaela Vidlakova remains to this day a very vivacious and active woman; she works in various bodies of the Jewish community, is on the board of the Terezin Initiative, and lectures at Czech and German schools. Mrs. Vidlakova is not just your ordinary senior citizen, and thus this interview with her was also an extraordinarily interesting one.

My family background

My paternal grandfather was named Siegfried Lauscher. He was born in 1865 in the town of Revnicov. He died in Terezin before World War II, in 1911 or 1912, so I didn’t have a chance to know him. All I know of him is that he worked in an office. A year or two before he turned 50, he suddenly fell ill and within a very short time died, most likely of an acute kidney infection. Back then doctors didn’t have antibiotics at their disposal. He was buried in the Jewish section of the town cemetery in Litomerice. After the war, this Jewish section of the cemetery was completely destroyed. My grandfather’s father was named Moritz Lauscher. My grandfather also had a sister, Anna, and a brother Karel, about whom I however don’t know any more than that.

My paternal grandmother was named Anna Schwarzova, married name Lauscherova and later Katzova. She was born in 1876 in Pribram. Her mother tongue was German. I don’t think that she had any sort of higher education; she was a housewife. Her two sons, Frantisek and Jiri, were still small when their father died. Grandma then moved to Liberec to live with her brother, who supported her for several years. Later she then moved to Prague; by then my father was already working, and was basically supporting the family. Frantisek was studying in Austria.

Grandma later remarried. She married Julius Katz, a Jew, nevertheless I’m not sure if they had a Jewish wedding. For a long time I didn’t even know that my grandpa was actually my step-grandfather. He loved me dearly, and I him too. It wasn’t until after the war that I realized that his name was different from ours. Grandma and Grandpa lived in Prague. They already spoke Czech at home. I don’t think that Grandpa had any education more advanced than high school. He likely worked as the sales director of a chocolate factory, Velimka, I think. Grandpa would have heaped chocolate on me, but even as a child I wasn’t that fond of sweets.

Grandma and Grandpa weren’t exceptionally religious in any way, they simply just upheld Jewish traditions. They used to go to synagogue for the High Holidays. They didn’t keep a kosher 6 household.

I remember Grandpa Katz as a smaller and somewhat round man. But by then he was actually almost 60. Back then I had the impression that he and Grandma were terribly old. Today, a 60-year-old is a young person to me. Grandpa was a merry and sociable person. Grandma held the reins of the household firmly in her hand.

My maternal grandfather was named Jaroslav Kohn. He was born in 1871 in Stare Hrady. Grandpa still observed certain Kohanite commandments, like for example he wouldn’t enter a cemetery [Editor’s note: the laws forbid Kohanim from coming into contact with the dead, or participating in funeral services by the grave, visiting a cemetery, etc.], but they didn’t keep a kosher household any longer. Perhaps they just avoided pork. The Kohn family was somewhat more religious than the Lauscher family. In the very least, they fasted for Yom Kippur. Grandpa was originally a shoemaker, but because he died in 1930, I didn’t know him at all. He died in Kamenice, and is buried at a Jewish cemetery in Prague.

My grandmother’s name was Ruzena Müllerova, and she was born in Chocen in 1881. I don’t think that she had any higher education. She was originally a housewife, but after Grandpa died, she supported herself by arranging or offering goods. She moved to Prague, and I remember that we used to see her a lot. We often went on walks together. I remember that she was quite strict. I didn’t want to eat very much, and she was willing to sit with me for over an hour with food that had gone absolutely cold, insisting that I finish it. I apparently had problems with insufficient saliva, but I wasn’t allowed to drink with my food, so I remember that food being quite a hardship for me. But Grandma was convinced that if I were to drink, I’d have a full stomach and would eat even less.

I think Grandma used to visit us during the holidays, and we used to visit her as well. My father was an incredibly tolerant person. Their relationship probably wasn’t particularly close, but they definitely respected one another and behaved decently towards each other. Grandma evidently wasn’t capable of expressing her feelings much, because I felt that warmth and kindness more from Grandma and Grandpa Katz. But on the other hand, she used to selflessly come and take care of me.

My father’s name was Jiri Lauscher. He was born during the time of Austria-Hungary in 1901 in Terezin, so actually as Georg, but all his life he then used the name Jiri. He was from a German environment, and his mother tongue was German. My father graduated from a German council school 7 and then took a two-year business course. Something like less advanced high school, but without a leaving exam. More advanced high school was four years with a leaving exam. I don’t know the official name of the school. Even though my father was from a German-speaking environment, he also spoke Czech.

My father was very Zionist-oriented. Already during World War I, when he was about 15, he led a group of younger boys, Tchelet Lavan. For some time he also organized hakhsharahs 8. His youth was composed of two directions. On the one hand, he supported his widowed mother and his older by two years brother in his studies, and on the other hand he worked very intensively for the Zionist movement.

My father had a brother, Frantisek, who was two years older than he. He graduated from university in chemistry, but I don’t know exactly when and where. He worked as a chemist in yeast production. He lived in Prague, but often traveled abroad on business. I remember him as a very pleasant person; I liked him very much and we were close also due to the fact that he didn’t have a family of his own.

Frantisek was no loner. He had a serious relationship, but in the end she married someone else. She was a big prewar Communist, and she married a person of the same convictions. They ran away from the Germans to Russia, where they however sent them to the Gulag 9 in Siberia. In the Gulag they were supposed to fell trees or something similarly physically demanding, but because they were both chemists, they were able to distil alcohol from the small sugar rations and some herbs. That was excellent for the guards, so they exempted them from hard labor. So they had a relatively decent position in the Gulag.

Another of Frantisek’s girlfriends died in a car accident. Then he had another girlfriend that he used to see, but he never started a family. I remember that he spoke Czech. I think that over the course of the First Republic 10 the entire family switched to Czech.

My father was 17 at the end of World War I, so he didn’t have to join the army. In 1920 he left for the United States of America. He wanted to study the establishing of orange groves in California, so he could later transfer this experience to Israel. But he couldn’t stand the climate there, so after a year he returned home.

Then in 1925 he moved to what was then Palestine, and became one of the founders of the Sarid kibbutz, which today is a medium-sized kibbutz close to Nazareth. There were other Czechs living there as well back then. They were starting from scratch in the swamps, living in tents, and the first thing they built was a calf barn, the second was a house for the children, and only then did they start building the rest.

To this day, it’s this second home of mine. When I arrive, they greet me like a daughter of the kibbutz, even though I wasn’t born there and I didn’t get over there for the first time until after 1989. At that time my father was 88 and wasn’t in good health, and so sent me in his place. We traveled there with a group of anti-Fascist fighters. At the kibbutz they told us stories of how in the beginning they ate only from tin bowls, and on top of that in two shifts, because there weren’t enough for everyone. And so I brought back with me as a souvenir this little bowl with the Sarid logo on it.

After five years of building the kibbutz, my father returned to Prague for my mother, whom he knew from Tchelet Lavan. He was planning a wedding and then for them to return together to Palestine. My parents had a Jewish wedding; they were married by Rabbi Sicher, back then the head rabbi of Prague. But for various family reasons the return to Israel kept begin postponed. Once it was the death of my mother’s father, then my mother was pregnant, but alas lost the child. When my mother got pregnant again, my parents finally decided that the conditions here for the birth of a child from a high-risk pregnancy were after all better. But before my parents had the chance to nurse me somewhat into shape, Hitler arrived and the jig was up.

My mother’s name was Irma, her maiden name was Kohnova, and was born in 1904 in Hermanuv Mestec in the Chrudim region. It was a Czech region, even her parents were already purely Czech-speaking Jews. My mother attended Czech schools and graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy at Charles University in Prague. She actually didn’t have a PhD, just state exams, and then went to work as a teacher right away. She became a teacher at a Jewish school on Jachymova Street in Prague. She began teaching Grade 1 while she was still at university.

My mother had a brother, Jiri, born in 1909. He graduated from electrical engineering, and worked with radios. At first he repaired them, then he set up a workshop and in England he had a store that sold and repaired radios. He married a Czech woman that had two children, Mirek and Zdenka. Her name was Marie, and she was the niece of Antonin Zapotocky 11. They had another two children together, Petr and Pavel. Right after the occupation of Czechoslovakia in March of 1939, Jiri emigrated to England. Marie still managed to join him with the children. After her death in 1960, he remarried in England, to an English woman named Susan, and had one more son, Simon.

Due to his departure, I barely know Jiri. Really, I only got to know him for the first time when he came to Prague after the war for the first postwar All-Sokol Slet [Meet] 12. Then he didn’t return here until 1968 13. I’m in regular written and occasionally even personal contact with Jiri’s children. Except for Mirek, that is, who died about two years ago. Uncle Jiri died in England in 1984.

My parents observed Jewish traditions at home. We went to synagogue for the High Holidays, and at home we celebrated all the Jewish holidays. My father wore a kippah only in the synagogue, or for Passover or when he was lighting candles. For Chanukkah we lit a candelabra at home, and sang Chanukkah songs. My mother also fasted on the 9th of Av [in Hebrew, Tisha B'av: fasting, is observed as a memory of the destruction of both the first and second Temple] and for Yom Kippur, but my father didn’t and they didn’t force me to. In our household Sabbath took place without prayer; we just made a fancier supper, had a white tablecloth and lit two candles.

Growing up

We didn’t observe Christmas or other non-Jewish holidays at all. My father was of the opinion that a Jew shouldn’t enter a Catholic church, not even as a tourist for example. He wouldn’t have forbidden Catholics to enter a synagogue, but he just thought that everyone should keep to his own.

We belonged to the middle class. My mother taught at a school and my father worked in a small furriery. It was managed by its Jewish owner, and my father was in charge of sales and production. There was an accountant, then just a master tradesman and some workers. My father used to take the train out of Prague to go to the factory. We didn’t have a car.

We lived in Prague in the neighborhood of Letna in a modern apartment on Hermanova Street. The apartment had central heating and hot water. We probably had parquet floors, but in one room there was this soft rubber with blue stripes. I liked it a lot back then, and loved playing there, because it was soft and wasn’t slippery. It wasn’t my room; I didn’t have a room of my own, but I played there the most, and I remember the rubber on that floor to this day. The apartment had this smaller kitchen and then a bedroom, a living room, and some sort of den of my father’s with bookcases.

All the appliances in the kitchen ran on electricity, and behind the kitchen there was a room for a maid, who lived with us. She was a young Czech girl named Terezie Hronickova. My mother used to go to school to teach, and this ‘Rezinka’ of ours took care of me. She loved me very much, and I her too. I remember that after the war I invited her to my graduation. It took me a while to find her. During the time of the Protectorate 14 Jews were forbidden to employ non-Jews 15. Rezinka got married and we lost contact with each other.

My parents had very nice furniture at home, designed by a friend of theirs from the Zionist movement, who left for Israel before the war started. It was in the modern and elegant style of the 1930s. The Germans later of course confiscated our furniture, and after the war my father found it in some warehouse of Jewish furniture. And although he had witnesses that testified that it was our furniture, even designed by an architect, while they did return it to him, he had to pay for it.

We didn’t have any pets at home. All I remember is that when I was completely little, I got a baby chick. There used to be a delicatessen on Jungmann Square in Prague, and before Easter they had little yellow chicks in the store window. I really liked them, so my parents bought me one little chick like that. That probably wasn’t the best thing to have in our apartment, so I most likely didn’t have it for too long. But I remember one photo where I’m playing with the chick. Later Jews weren’t even allowed to have animals.

While we were still living on Letna, Rezinka would take care of me during the day, who besides me also took care of the household and cooking. We didn’t cook kosher at home. The only Jewish food that we liked a lot were two side dishes. One was roasted semolina, and then gratings, in Yiddish ferverlach. Ferverlach isn’t grated bread, but dense noodle dough that’s grated on a rough grater, then left to dry, is roasted and then has either soup stock or just hot water poured over it. It’s also a side dish, and is very good.

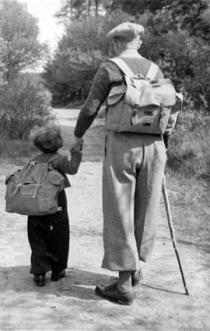

On Saturday afternoon and on Sunday my father would go on walks with me, which is what I liked best. I’ve got one old, old memory of my father pushing me in a sports carriage, and that he switched the handle so I could see in front. When I grew up a little, we’d always take the tram to the last stop and go on an outing. My parents were enthusiastic hikers. When the Germans occupied us, I was two years old, so before I got old enough for my parents to be able to do more things with me, everything had already been forbidden.

I don’t know exactly when it was, but I think that sometime during 1941 the Germans forced us out of our apartment. We moved to Zizkov [a Prague neighborhood] into an apartment with Grandma and Grandpa Katz, who lived in a zone where they weren’t evicting Jews. It was an unattractive quarter and an old, uninteresting building. But because they had a large apartment, we had to move in with them. While we were still living there together as a family, it wasn’t all that tragic. My father, mother and I had the use of one room. I think the other grandmother or someone else from the family was also living there.

When we then lived in Zizkov, Grandma and I would at least walk along U Rajske Zahrady Street, which led along Rieger Gardens; I was no longer allowed into the park itself anymore either. There was this open area there, now it’s been built on, where boys used to play soccer. But it wasn’t an official park. It was one of the few places where Jewish children could go. Then we also used to go to the Jewish cemetery in Zizkov, and used to play amongst the graves; there was even some sort of Jewish musical event there, the audience would sit on the edges of the graves.

I didn’t start attending school until after the war. Before the war my mother didn’t teach me, I was completely self-taught. I learned to read from signs that I saw around Prague. I think that at the age of five I was already normally reading books.

I didn’t classify my friends according to origin or religion. The fact that I used to get gifts for Chanukkah and others for Christmas I just took as that everyone’s got their own thing. From the pre-Terezin period I remember my Jewish friend Pavel Fuchs, who was the son of Mr. Fuchs, and engineer who was later the chairman of the Council of Jewish Communities in Prague. I’ve known Pavel since I was little. He now lives in Seattle.

Both my parents voted for the Social Democrats, but they weren’t members of the party, just sympathizers. For some time my mother was a bit leftist, and was involved in the so-called Red Help, which was something like assistance for people who were escaping Germany, running away from Hitler. It was probably some sort of leftist-oriented organization, because a lot of Communists and Social Democrats were escaping from Germany. What exactly she did for them, I have no idea.

My father and mother were of course both members of the Jewish community. My mother was an exercise instructor in Maccabi 16. After the occupation, groups were being prepared in the community for emigration to Palestine. So both my parents led so-called retraining courses, where young people practiced various skills necessary for life in Palestine. My mother taught childcare and my father handicrafts. When even the Jewish school was then closed, my mother organized a school group right in our apartment.

Prior to the war, I never encountered expressly aggressive personal anti-Semitism. But I was of course aware that they’d moved us out of our apartment, and was very much aware of not being allowed to go to any parks.

I recall that when we were still living on Letna, there where today there is that horse merry-go-round by the Technical Museum, there used to be this old man who had a real live horse, Asenka, with a carriage, and he’d make money by driving children around in the park. As a Jewish child this was forbidden to me, but I remember that I did go for a ride like this with him once. I later asked my mother how it was possible, and she told me that this man, when he would be going home in the evening, would give a ride down the street to Jewish children that would occasionally be waiting there for him. I must’ve been around four back then. He was this old, small, and terribly kind man.

After the war, no one went so far as to call me names either. I know that there were some guys in school who had anti-Semitic attitudes, but they never actually came out and said anything to me, we simply weren’t friends. And it was only later that I found out from someone else that it was because of me being Jewish.

Before the war broke out, my parents were of course thinking about whether we shouldn’t leave for Palestine. But they didn’t want to leave my grandparents alone, when everything was becoming so gloomy and black.

Grandma and Grandpa Katz, Uncle Frantisek and Grandma Kohnova were the first to be transported to Terezin. My grandparents were soon after that transported eastward, and I never saw them again. Grandma Kohnova perished in Treblinka 17 in 1942. My mother told me that I fell ill after every transport. I don’t remember crying or anything, but whenever someone from the family was transported, the next day I apparently had a temperature of almost 40 ºC, which then immediately came down again.

During the war

I bore our own summons to the transport considerably better. I remember that at that time my parents allowed me to do something that I’d never been allowed before, nor since. And that was to draw on the walls in the apartment. Earlier, when I’d tried to do it with a pencil behind my bed, a huge to-do ensued. I remember that I was so preoccupied by this drawing on the walls that I completely forgot that the next morning we were going to the transport. As well, life in Prague under the Nuremberg Laws was very circumscribed, I’d never liked it that much in Zizkov, and so I also somewhat perceived our transport as an interesting change. I wasn’t capable of imagining that things could get even worse.

My parents hid a lot of our things with the family of my father’s cousin, Viktor Lauscher. Viktor’s father was the brother of my father’s father, Siegfried Lauscher. Viktor’s mother was probably from Hungary, her name was Terezie, and we called her Aunt Terci. Viktor married Marie, a German woman who’d worked as their servant, so at that time he wasn’t in danger of being deported. His wife was a very good and kind person. She had lots of our things, like family photographs and valuables. After the war she also returned everything properly. Viktor and Marie had two daughters, Zuzana and Lida.

Other things we and mainly Grandma Kohnova stored with the mother and sister of Marie, the non-Jewish wife of Uncle Jiri. Grandma even transferred the title to her house in the Prague quarter of Zahradni Mesto [Garden City]. But there we never got our things back after the war. They even claimed that during the war they themselves hadn’t had anything to eat, and that they’d had to sell them.

I don’t remember anymore how we got to the assembly point at the Veletzni palac [Trade Fair Palace], all I know is that I had a little rucksack on my back, and that I was supposed to take care of it and not take it off. This took place in the winter of 1942. We didn’t spend more than three days there. We slept on straw mattresses amongst the luggage; we had our own blankets, and I remember it being terribly cold, and there being long queues for the latrines. But at the same time, the fact that there was a group of children there was very interesting for me, and I was finally among children again.

I got to Terezin for my sixth birthday. I remember one thing from the train trip, from the town of Sedlec by Prague, where there once used to be a restaurant inside a big concrete elephant. My mother called me to the window to have a look at the elephant. I didn’t know what one looked like, because we were forbidden from going to the zoo. So she wanted to show it to me, and said that on the way back we’d take another look at it.

Uncle Frantisek, who worked in the bakery in Terezin, swapped shifts with someone so that he could come and greet us. He risked his life, and already during the trip from the train station he contacted my father and gave him some advice on how to act when entering Terezin. We managed to crawl under some rope somewhere, so we did pass through the shloiska [quarantine], but not the luggage inspection. And so everything that we had with us, we got in like this. My father had his tools with him, and samples from the toy workshop where he worked as a laborer after he was fired from his job for being a Jew.

Plus I think that Mr. Freiberg was there, an engineer whom my father knew from prewar times. He told my father that the Germans wanted to utilize wood remnants in some way, and that he could get a ‘Kommandaturauftrag,’ meaning a job from the command. Back in Prague I had seen some child at the Jewish cemetery with a wooden dog that had strings running through it that you could use to manipulate it, make it wag its head and tail. I liked that very much, and my father traced it and during his lunch break he made that Disney dog Pluto for me on a lathe in the workshop. I took Pluto, my favorite toy, with me to Terezin.

While still in the shloiska, my father showed them this toy and demonstrated with it how to utilize wood remnants. That saved my father as well as us from immediately being sent further on, because part of our transport didn’t even leave the shloiska, and was transported away. That took place towards the end of December 1942. The dog was saved and became a family relic, and today sits on my bookshelf. That’s how my father got to the Bauhof [Editor’s note: Bauhof: a construction yard; in Terezin a place where there were various workshops].

My father wanted to get to work right away, but they told him, ‘Lauscher, don’t be crazy, you have to go slow. If you’ve got ‘Kommandaturauftrag,’ it’s got to last you. So first order some lathe tools.’ He said, ‘But I’ve got some.’ ‘That doesn’t matter, hide those away. First order them. Then when you get them, order some gouges.’ That’s what they advised him to do, that you had to delay it as much as possible, so that it would last as long as possible.

In the end he never got to the toys, because they transferred him to the carpenters, which at that time was also relatively good work to have. He had access to materials, both raw materials as well as remnants, which could be used for heating fuel. As for the raw material, you could always save up a bit, for when someone needed something made, like a shelf for example. And of course if it was the cook that needed it, in exchange you’d get a dumpling or the opportunity to scrape out the kettle. Even when the kettle was completely empty, you could still scrape out a mess tin’s worth of coffee cream, and the family had a treat.

My mother was known for her teaching work, so they immediately summoned her to ‘Jugendfürsorge’ [caring for the young]; she first worked in the girls’ ‘Heim’ [home] and later became the head of the ‘Tagesheim’ [daycare for children whose parents were out working]. That was a facility for small children who for some reason didn’t live in a ‘Kinderheim’ [children’s homes] and needed to be watched during the day. The ‘Tagesheim’ was in Street L, No. 200. Although teaching was forbidden, she basically ran this one-room schoolhouse there, so after the war all the children that survived were able to not only enter a class appropriate for their age, but many times a grade or two higher than where they would have belonged.

My mother was possessed by teaching her entire life, and I think that in Terezin even more so than otherwise. The ‘Jugendfürsorge,’ or care for the young, was located relatively near the ‘Ältestenrat’ [Council of Elders]. My parents knew that the transports were being dispatched eastward, and that they were going towards something worse. But that the transports were headed for extermination camps, that I don’t think they knew.

When we arrived in Terezin, I spent the first while in a ‘Kinderheim’ beside the town hall. Back then my mother was living somewhere in the women’s barracks and my father was living at the Sudeten barracks. After not quite two months I fell ill. First I got the standard ‘Terezinka,’ or dysentery. There wasn’t anyplace to isolate sick children, so I remained in the ‘Heim’ amongst the children. To this day I remember spending nights sitting on the toilet, lit by a blue light, because it wasn’t even any point in getting off it. Not to mention the fact that I didn’t even have a bed. There were so many children there that I slept on two benches butted up against each other.

Then I got three infectious diseases at once: typhus, scarlet fever and measles. So one starlit night two gentlemen carried me to the hospital, a hospital run by Dr. Schaffy, across from the Magdeburg barracks. When my parents were looking for me at the ‘Kinderheim’ the next day and they told them that someone had carried me off in the night, they were in shock. It took them a while to find me. Then my mother went to ask Schaffy what was the matter with me, and he asked her, ‘Ist sie ein Brustkind?’ My mother said, ‘Ja, neun Monate.’ ‘Dann hält sie es wahrscheinlich aus.’ [‘Was she breastfed?’ – ‘Yes, nine months.’ – ‘So she’ll most likely survive.’]

My mother used to say that Dr. Schaffy was a distant and curt person. But we children loved him. He was a wonderful man. His visits were holidays, he’d have fun and play with every child, and at the same time would manage to do his checkup. I don’t know what he used, he’d scarcely have had much medicine at his disposal. I spent 13 months with Schaffy, while there I also had hepatitis and some sort of heart infection, probably as a result of the fevers, and if I’m to be truthful, I was very happy there.

For some time I shared a room with some older boys, who were around 15 or 17. One was named Pepik and the other was Jirka Foltyn, and they knew an endless number of songs. Then there was a boy the same age as me from Berlin, by the name of Horst, I don’t remember his surname exactly anymore, from whom I learned to speak German perfectly, I don’t even know how. I even had quite a close relative there. When they brought me to the hospital that time, in the morning the door opened and one nurse asked, ‘Is there a Mischa Lauscherova here somewhere?’ When I raised my hand, she said, ‘I’m your Aunt Hanka.’ Hana Schiffova, nee Müllerova, was my mother’s cousin, who happened to be working for Dr. Schaffy as a nurse.

Hanka survived Auschwitz and other camps, but not her husband. After the war Hanka married Karel Bruml and moved to the USA. Karel Bruml also passed through the Nazi camps, including Auschwitz. In Terezin he worked in the technical workshop along with other artists like Fritta or Haas. In the USA he also made a living as an artist. Hanka took psychology in America at the university in Washington, D.C. She became a psychologist and later the head of the psychiatric ward at a hospital in Falls Church.

We kept in touch until her death a few years ago in the USA; she was more like my older sister. She supported us after the war, but even later she used to send packages with good quality clothing, canned food and other things that were needed back then and were allowed to be sent. But mainly she gave us the feeling that there was someone who was interested in us, who was family.

In the afternoon, when the ‘Tagesheim’ would end, my mother would then go and teach the children in the hospital. As it was the infections disease pavilion, she didn’t go in the rooms, but Dr. Schaffy allowed her to teach children that were recuperating, outside in the courtyard.

When they discharged me from the hospital in March 1944, I went to live with my parents. My father and two of his colleagues from the ‘Bauhof’ had built a mansard up in the city hall building. The three of them were living together up in the attic there. My father made my mother this little nook beside the mansard; he’d built this wooden platform with a straw mattress on which my mother slept. It had a wardrobe on one side, and on the other a blanket as a curtain. It had no window, just a hole in the roof. But my mother would just sleep there. When the men would go to the ‘Bauhof,’ which was very early in the morning, she’d go to that little room, which could at least be heated a bit.

So that’s where I lived after being discharged from the hospital. The problem was that the mansard was on the third floor, and for me, who’d been discharged from the hospital with a heart defect after those infections, it was too many steps. I always had to whistle and wait downstairs until one of my parents arrived to carry me at least most of the way up. During the day I attended the ‘Tagesheim.’

A child’s experiences from Terezin are of course completely different from those I’d have had there as an adult. I had a child’s problems, which from the viewpoint of an adult seem to be trifles, but for a small child they were important things. I was quite solitary for some time, and I remember my mother asking me why I didn’t play with other children. Apparently I proclaimed, ‘I don’t want to be friends with anyone. Every time I make friends with someone, they take him away to the transport.’

My responsibility was to make the rounds to fetch food at lunch. My father made me a wooden ‘traga’ for the mess tins. A ‘traga’ was this low wooden box with a handle, it’s also called a tool tray, similar to what tradesmen have. Lunch was given out in three places, always in the courtyard of the barracks, so I had to make the rounds to the children’s kitchen, the normal one for my mother, and for my father to the one for those doing heavy labor. It was a relatively demanding task for a child of seven to run around Terezin, stand in a queue each time, and bring it all home.

In the meantime there would often be air raid warnings, when you weren’t allowed to walk out in the street. In that case I’d always run into a nearby doorway and would zigzag my way though Terezin across courtyards and along all sorts of pathways with the food. To this day I remember the sad, stooped figures, of old Jews, mostly from Germany, that would stand by the queue and quietly addressed those waiting, me as well, ‘Bitte, nehmen Sie die Suppe?’ Sie! A seven-year old child! I felt very sorry for them. [In German: ‘Please, are you taking the soup?’ The form of the pronoun ‘you’ used, ‘Sie,’ is a formal, polite version that an adult would not normally use to address a child].

I always thought of my grandmothers and grandfather, how they must be faring somewhere there in Poland, whether they also have to beg for food. I didn’t know that they were long since dead. I think that this is one of the reasons why today I work for the social committee at the Jewish community.

Then I discovered a man there who spoke German and was also named Lauscher. So I adopted him as my substitute grandfather. For some time he actually did come and visit us; he and my parents discovered that he belonged to some branch of the family. But fairly soon they transported him away. I missed having a grandfather very much.

I also remember standing in the food queue and that some of us children were shoving each other back and forth, and some older girl yelled at me, ‘Why are you fighting here, isn’t your father in the transport?’ I remember being very ashamed that my father wasn’t in the transport. But my father did end up in the transport. He was even already in the departure barracks. At night a gale blew and tore some roofs from some buildings. An SS soldier came to the foreman of the ‘Bauhof,’ that they had to immediately repair them. But the foreman objected, ‘How am I supposed to immediately fix them, when my last carpenters are in the transport?’ To this the SS soldier replied, ‘The transport isn’t leaving yet, so have them go to work.’

They were then looking for volunteers in the departure barracks. Three of them volunteered, including my father. In the morning they went to work, and in the evening the returned to the marshaling area. The second day they again went to work on the repairs and in the evening they returned. The third morning they again left for work, and when they returned in the evening, the transport was gone. And that was the last transport to leave Terezin. People had said to my father, ‘Lauscher, you’re stupid, you’re in the transport and you’re still going to work!’ As you can see, it saved his life.

At that time my mother wanted to volunteer for the transport, because we’d said to each other that we’d always be together. But my father refused that. ‘Nothing doing,’ he said. ‘Here you after all do have a certain chance of surviving. Who knows what will be there, and with a child, rather not.’ If my mother would have volunteered back then, I’d have gone and my father would have stayed. We got lucky, one time out of many. They kept my mother in Terezin thanks to the ‘Jugendfürsorge,’ and then she got a letter of praise for her work from Leo Baeck, who she respected very much. Leo Baeck was a renowned and very respected rabbi from Berlin. In Terezin he was in charge of the ‘Jugendfürsorge.’

Another bit of luck came about because I was in the hospital, because back then there were regulations according to which entire families were being sent, and so my stay in the hospital protected us. However, shortly after my discharge the regulations changed and then on the contrary the entire hospital left on the transport, doctors, nurses and all.

I remember how in 1945 transports from other concentration camps began arriving in Terezin. One evening my mother told my father to go have a look if he couldn’t find Uncle Frantisek there. Whereupon I began crying and said that I didn’t want my uncle to be there. My mother asked me, ‘Why don’t you want that? After all, that would be great if your uncle returned.’ I said, ‘But did you see what those people look like? I don’t want my uncle to look like that!’ That was my child’s view of the world. My uncle never returned to us. He didn’t survive Auschwitz. He perished in 1943.

One day the town hall had to be vacated for the Germans, and we were forced to relocate. We moved a ways over, to a corner house in Q Street, No. 609; the town hall was No. 619. There we again lived in the attic, but we didn’t have a mansard, just this sort of alcove. The interesting thing about this place was that Karl Bernman’s choir used to practice nearby. So every night I would go to sleep to the sounds of ‘Blodkovo,’ ‘In The Well,’ or ‘The Brandenburgers in Bohemia.’ Those are my childhood lullabies.

In the spring of 1945 we moved to L 227, on Bahnhofstrasse. There we got one small room for all of us. As a child I was well trained, so whenever I’d be walking in Terezin and would find a small piece of coal, wood or anything else combustible on the ground, it would immediately disappear into my pants pocket. Once I even managed to find a potato. I brought it home, overjoyed, but my father scolded me emphatically, that one didn’t steal food, that maybe because of that someone won’t get their ration. I remember that we had a small stove in the room, on which we then cooked the potato, cut into very thin slices. My mother was basically a miraculous cook. When I for example brought some barley from the kitchen, I have no idea how, but she made excellent ‘meatballs’ from them on rationed margarine.

When my uncle was still in Terezin, he once took a yeast dumpling in the bakery, they used to call them ‘blbouny,’ and baked it into a bun, wrapped it in a handkerchief and brought it to me while it was still warm. Another unforgettable memory is a mouth harmonica that I got for my sixth birthday. My uncle had traded a piece of bread for it, because as a worker in the bakery he had the ability to get to extra bread. And for this bread he got me a Hohner harmonica that I have to this day, and which I had with me in the hospital at Dr. Schaffer’s. I guess they had to disinfect it afterwards. I remember that when I wrote letters in the hospital, Hanka the nurse would always iron them so that they could leave the hospital. That was disinfection.

After the war

One day a rumor began circulating that the war was over. So we wanted to go to the end of the street, where the ghetto actually ended, but my mother didn’t want to let me go there. In the end we found out that the Russians hadn’t arrived yet, but that on the contrary it was the Germans as they were departing. They threw a hand grenade there, and it injured someone quite seriously. But then the Russians really did arrive, and Terezin really was liberated. But we remained in Terezin until the end of May, in quarantine.

I and my friend Stepka Sommer, the now already deceased cellist Rafael Sommer, and a handful of other children used to go to the garden, where our task was to air out the hothouse, water the plants and take care of refilling this big storage tank with water. It was a lot of fun for us, because we used to bathe in that large barrel, and after work we played excellent games in the garden. For that we’d get a head of lettuce, a kohlrabi or even a cucumber every day. After years of not seeing the smallest piece of fresh vegetable!

Back then my father took his coveralls and a toolbox with some tools and secretly smuggled himself out of Terezin. He was born there, so he knew the area very well. He left for Prague, where he arranged an apartment for us in the building we’d originally lived in, and other things. It wasn’t our original apartment, because that had been given to Dr. Fischl, who’d also returned from the concentration camps, where he’d lost his wife and child, and wanted to open a clinic in our apartment. He and my father came to an agreement that he’d keep the larger apartment, which enabled him to have a waiting room as well as an examination room, and we lived in the two-room apartment next door.

My first feeling of freedom is connected with a young soldier from the Russian army, who passed by the garden on a horse. We children were joyfully waving at him, and he came over to us, and pulled us up into the saddle with him, one after the other, and took us for rides. For me that was a truly fantastic feeling of liberation, when I was sitting with that young man on that horse and we were riding around in the Bohusovice basin. Our trip back to Prague was once again by train. I remember it, because my mother showed me Rip [a hill visible from far away, whose peak is at 465 m ASL], and that elephant in Sedlec again.

But we didn’t stay in Prague for long, because at that time Premysl Pitter already began organizing the ‘Chateaux’ drive for children that had returned from concentration camps. As an educator our mother couldn’t not participate, so she became one of the employees at the Kamenice chateau. We were among the first there. My mother began to mainly organize classes, because there were children of all age categories.

Back then my mother was tutoring children over a wide age range, because they needed to catch up on material from their relevant school grades over the summer. There weren’t classes all day. They were actually these little study groups, each one about two to three hours a day. But for my mother that meant at least five times two or three hours a day. In the meantime we played and went on walks, bathed and relaxed in all sorts of ways. I remember that swimming was the main attraction, because there were very nice ponds in the area, and up until then we’d never experienced real bathing. All we knew from Terezin was a battered enamel washbasin and once in a while, when it rained in the summer, we’d splashed about joyfully under the rainspout.

In September 1945 I had to go to school, so at the end of August we returned home to Prague. I was eight and a half at that time, so I actually already belonged in Grade 3. We went to the elementary school under Letna, where I belonged according to my address. But there they said that if I knew how to read and write, the most they could do was put me in Grade 3. But I’d already known how to read and write even before Terezin.

My mother felt sorry for me, she knew that I’d be extremely bored in Grade 3. Then she heard about a language school in Charvatova Street, which was supported by the British Council, and where they taught English. Because it was a selective school, you had to pass an entrance exam. Right when my mother and I arrived, they were doing entrance exams for Grade 5, and the examiner offered that I could try it with them, that what I’d manage, I’d manage. The exam was composed of dictation, composition and some math, and I easily passed it with straight A’s. The teacher began apologizing to my mother, that they couldn’t let a child of eight-and-a-half into Grade 5, that I couldn’t be among children that much older than I. And so they accepted me into Grade 4.

I attended English school for about a half or three quarters of a year, when one of Winton’s children 18 returned to Czechoslovakia. It was Eva Schulmannova, who was two years older than I. Her father had served in the army in England during the war, and her mother had died in Auschwitz. Doctor Schulmann remarried in England, I think he married a girl from the family that had been taking care of Eva. They returned to Czechoslovakia and Eva, who’d left here as a little girl, didn’t know a word of Czech. My mother was preparing her for entrance into a Czech school. As I already knew a few words of English, they put us together, so I could teach her Czech. But Eva had liked it in England a lot, was unhappy here, and so refused to learn Czech, thanks to which I on the other hand learned English quite well. Later Eva of course managed to learn Czech, and we also became friends.

After the war I attended religion classes 19 at the Jewish community for a few years, until about 1949. There were about three or four of us children there. At the beginning there were probably even more of us, but because the instruction wasn’t very good, only a few of us remained. The cantor and rabbi taught us Hebrew, but not the modern version, which for me was in conflict with how my father spoke. The manner of instruction didn’t correspond to modern methods either. Although we didn’t know Hebrew, we had to learn, completely by rote, the beginnings of the individual weekly paragraphs of the Torah. I very much disliked going there, and that’s also a reason why many children also refused it at a time after the war when it was still possible. Later of course, attending religion classes meant showing ‘lack of perspective’ and not having the chance to keep attending school. [Editor’s note: religious inclinations of any sort were highly frowned upon by the Communist regime.]

I attended the English school until 1948 20, when the school was closed due to its patronage by the British Council. Then I transferred to the socialist middle school of Frantiska Plaminkova, which was a nine-year school. There we took a so-called small leaving exam, which were final exams, and then you had to do entrance exams for gymnazium [academic high school]. I passed the final exams with straight A’s, as well as the entrance exams for the French high school. Nevertheless, I then received a notification that I couldn’t be accepted because of there being too many applicants. However, children with C’s on the entrance and final exams were being accepted. So we appealed and appealed, until we finally succeeded and I really did finally get into that French high school.

After the war my mother didn’t return to school as a teacher, but taught at home, privately, mainly languages. At that time there was a great shortage of language teachers, and my mother knew English, German, French and Latin. Upon our return my father made a living as a business broker. After the war, lots of military material remained here, and some sort of use had to be found for it, to sell it, offer it or manufacture something from it. I remember parachutes from beautiful silk. But what to do with so many parachutes? I know that my father found some company that colored them and sewed fantastic winter jackets from them.

My father basically looked around for who was offering what and how it could be utilized and sold. That’s how he made a living until 1948, when the Israeli embassy opened in Prague. The first one to start working there was actually my mother, who taught the first ambassador Czech and also worked there as a translator. But after some time she left, because it was too much for her. Work at the embassy, caring for me and the household. And I also think that she missed teaching. My father knew English, German and mainly Hebrew well. About two months after my mother, he also started at the embassy and began working there as a phone operator.

My parents were planning to leave for Israel. But right after the war my father was still recuperating from tuberculosis, and the doctors were saying that if he arrived into that heat, the illness could return. On top of that my mother had kidney problems, so my parents wanted to get well first. Then they wanted to leave when they started working at the Israeli embassy, but back then the embassy asked them to wait a while, that they needed them here.

Right then a massive wave of aliyah was taking place. A final date was set after which emigration would no longer be possible, but my parents were promised that the Czech employees of the embassy would be allowed to leave even after this date. But it was a promise from Communists, and when my parents began to pack, saying that they’d like to leave now, they weren’t issued passports.

When the Slansky trial 21 began, my father said that it seemed to him that things were getting bad, and that it would be good to get out at any cost. So my parents decided that we’d try to leave illegally. Our departure back then was organized by the Israeli embassy. Other people left with us, Helena Bejkovska, and Mrs. Pavla Ehrmannova, the mother-in-law of Zeev Scheck. I don’t know if the mistake was on the part of Mossad [Israeli intelligence service], which was allegedly organizing our departure out of Vienna, or if someone here made a mistake. The fact remains that in April 1953 they caught us at the border. Later they got Helena Bejkovska out through Germany and Sweden, but one person can get across the border more easily than an entire family. Mrs. Ehrmannova was officially a citizen of Austria, so they got her out later in an official manner. But we had to stay here.

We had a trial, but luckily in the meantime President Gottwald 22 died, so when President Zapotocky took office there was an amnesty. I was 16, so I was still a minor, but even so the Communists tried to make a big political trial out of it. The Israeli embassy, espionage and so on. This bubble luckily burst, and all that remained was an attempt to leave the republic. I spent a half year in remand custody in Bartolomejska Street and then in jail in Pankrac. I got a half-year suspended sentence, which was very mild for the times. My mother got one and a half years hard time, but they subtracted a year due to the amnesty and she’d spent a half year in remand custody, so she also went straight home after the trial. My father was sentenced to two years, so after the trial they put him in jail in Valdice for another half year.

Probably the worst thing was that they confiscated our apartment, even though they didn’t have the right, as there was nothing like that in the sentence. When my mother and I were leaving the courthouse, we thought that we were going home, but we found out that some Mr. Liska was living there, apparently an employee of the StB 23. Our things were piled up in the cellar and we had no place to go.

So a couple of good friends moved us both into their not overly large apartments. One was Greta Bieglova, who lived on Veverkova Street. She had a room and a kitchen, where she lived with her son and where she had a home workshop, and despite that she took us in as well. Her son was a friend of mine from back during the Terezin days.

Then we lived with the Webers; Mr. Weber was a friend of my father’s from Terezin from prewar times. His wife, Ilse Weberova, a children’s nurse and a Terezin poet, perished in Auschwitz along with little eight-year-old Tomik. We also lived for some time with the family of my classmate from English school, Jaroslav Svab. For some time I was also with Jindra Lion, a journalist with Svobodne slovo, and his wife Hanka.

It took about three months before we found some at least halfway decent accommodation. At first they wanted to assign us one horrible apartment with no bathroom, toilet or kitchen. We succeeded in refusing it and finally they gave us a bachelor apartment in Strasnice, without central heating, but clean and dry. They said that if we didn’t take it, we’d have to leave Prague, so in the end we took it. After my father’s return we managed to exchange this apartment for another one in the Vinohrady district.

After being released from jail, my father was able to return to the embassy, because they declared that they hadn’t terminated his employment contract and that he was still their employee. My mother continued to teach privately. Even though back then employment was mandatory, my mother received a certificate from the Freedom Fighters’ Association that due to having been imprisoned she wasn’t able to work in a regular job. The National Committee allowed her to teach at home, she paid taxes, but was insured and it went towards her pension. Relatively few people were allowed to work like this back then.

Before our attempt at emigration I’d been attending the French high school. Back then the principal was Vanda Mouckova-Zavodska, whom I liked and I think that she liked me as well. But when I came to see her, saying that I’d been given amnesty and that I had to be looked upon as someone without a record, she said that she didn’t care, that such elements had no business being at her school. During the war she’d been jailed for being a Communist, perhaps even sentenced to death, so I thought that she’d have a certain amount of understanding for people from jail, but evidently her Communist ideals were stronger. So I remained without a high school diploma and entered the work force.

I began working for Potravinoprojekt as a technical draftswoman, or more precisely as someone that had studied technical drawing. I basically drew projects with Indian ink, and my starting salary was 450 crowns. [Editor’s note: with Act No. 41/1953 on Monetary Reform, the gold content of the crown was set (unrealistically and out of context) at 0.123426 g of gold, which remained in place until the end of the 1980s.] The manager of our office was Ing. Fanta, a prewar capitalist, whom they were also persecuting and threw him out of everywhere they could. When he heard my story, he willingly took me on and was very nice and decent to me. My other co-workers were excellent too, they took care of me and understood my life’s trials. I even met Mrs. Eliska Schrackerova there, a lady my mother’s age, who’d also survived Terezin. I have very fond memories of that year and a half.

At that time I finished my high school degree at night school, and in 1955 I finally graduated. My previous report card as well as the one from the school-leaving exam had straight A’s, so according to the rules I was supposed to have been admitted to university without having to take entrance exams. Back then I didn’t know that, nevertheless I once again had straight A’s on the exams for the Faculty of Science at Charles University, where I’d applied. But I received a notification where it once again said: ‘You passed the exams, but due to the high number of applicants, we were unable to accept you.’

They recommended that I apply to agricultural college or economics, because they had a shortage of students. But I said that I wanted to study biology, so I kept appealing and appealing. Finally it went all the way up to the Office of the President and back to the rector’s office and dean’s office, and then they finally accepted me, after the summer holidays. Then two years later they tried to expel me, but once again it somehow worked out, so in the end I graduated. My thesis was on the metabolism of sugar in insects. I graduated in 1960.

After school Docent Kleinzeller took me under his wing upon the recommendation of his mother, who’d also been in Terezin and knew my parents. He brought me to the Institute of Biology at the Academy of Sciences to do a residency with him. Docent Kleinzeller had originally been a very fervent Communist; though he’d been in England during the war, he was a member of the [Communist] Party 24. It must be said that he wasn’t a fanatic, and apparently the Slansky Trials had opened his eyes a bit. He then recommended me to his former student, Pavel Fabry, who worked at the Nutrition Research Institute in the Krc area of Prague. Pavel was involved in the ROH 25 and so he succeeded in pushing me through to the lab at the institute.

So although my father worked at the Israeli embassy and a criminal record, there were enough decent and courageous people who helped me and did things for the benefit of an unpopular a creature as at that time was I.

I then remained in Krc until 1994, when I retired. I worked in a research lab there as a regular researcher. Quite a few Jewish physicians worked there, such as Dr. Brod, Dr. Fabry, Dr. Braun, and Dr. Bergmann. They were mostly very well liked, so I’ve got to say that I didn’t feel any anti-Semitism there. On the contrary, people expressed their sympathies. It could also have been as a result of the Prague Spring, when Pavel Kohout wrote an article entitled ‘Once there was a small country, surrounded...’ and people clearly understood the parallel between Czechoslovakia during the time of occupation and Israel during the time of Arab siege. [Kohout, Pavel (b. 1928): a Czech poet, writer, playwright, translator and important samizdat and exile author. He was also present at the birth of Charta 77.]

In jail I developed an infection of the sciatic nerve, which went untreated for a half year back then, and gave me a lot of trouble later. So the doctor gave me a voucher for a spa, where I met Milos Vidlak, my future husband. I was 17, he was 15 years older, and very educated and cultured, which was something I missed in guys my age. Milos was from Prague, and we went out for the entire time of my university studies, and after school in 1960 we got married. I didn’t know any Jewish guy that suited me.

My husband was a graduate of the Faculty of Philosophy at Charles University. For a long time he worked for the Invalids’ Association, in the area of work, wages and care for invalids in general. Due to the Communists he didn’t finish his PhD until 1968, and then worked for the Ministry of Social Affairs.

We lived with my husband’s parents in a house on Na Vetrniku Street in Prague. Milos may not have been a Jew, but in the beginning he gave the impression of a big Semitophile. But after the wedding that began to gradually change, until he began to behave practically like an anti-Semite. My husband was very much an anti-Communist, and would for example throw in my face that it was actually the Jews that began with Communism. In the end the Jews were even responsible for scorched soup.

I don't know whence it came in him and why. Before we were married, he’d even attend synagogue with me. But I think that it wasn’t so much an expression of anti-Semitism as of compensation for certain complexes. Back then he wasn’t a university graduate yet, and I was already working at a research institute. I think that he simply didn’t feel good, and compensated for that by attacking me in an area that he knew was the most sensitive for me. Thanks to that we became estranged, of course. We didn’t get divorced, because in the meantime, in 1963 our son Daniel was born. Back then I had practically no place to go, I wouldn’t have been granted an apartment anyways.

Daniel also had excellent and loving grandparents. I liked my father-in-law, Filip Vidlak, as well as my mother-in-law, Marie Vidlakova, and they loved Daniel. I’m sure that my mother-in-law realized how unstable her son was, and was glad that it was at least the way it was. After she died, I kept taking care of my father-in-law for quite a bit longer; he lived with us, and at the age of 90 would still cut the grass out in the yard.

My husband was as a father kind to our son, so I said to myself that I wouldn’t wreck our son’s family. And so when I felt that things had gone too far, which was after about six years, we stopped functioning as husband and wife, but we managed to keep the family going. We lived beside each other, each doing his own thing. Each one of us had his own room, but we usually ate together. Otherwise we basically lived together like two roommates with their own lives. We both faithfully put the money we made into a common pot and each then took what he really needed. When we needed to buy something bigger, we came to an agreement and bought it from our joint funds.

From December to April I spent all Saturdays and Sundays with my son in the mountains. On weekends my son and I would go to my parents’ cottage. Until my son was born, my parents and I would often go on trips, as we were ardent hikers. Sometimes my husband would come along as well. After Daniel was born, it was clear that we wouldn’t be able to go hiking for some time, so we decided to buy a cottage somewhere near Prague. We basically bought the cheapest thing available at the time; we said to ourselves that it would be for about five or six years, and then we’d sell it and start hiking again.

But in the meantime my father had a serious heart attack, and so we ended up keeping the cottage. My father liked it there, the cottage is in the forest, a little above Kytín by Mnisek pod Brdy. My father could go on walks, and liked working on his woodworking hobby there, painting, making and fixing furniture. We’ve still got the cottage to this day; it may not have electricity, the water is from a well and the toilet is in an outhouse, but it’s nice there. In 1967 some friends of my parents emigrated to Israel, and sold us their car, a Fiat 600. Otherwise back then you had to wait a terribly long time for a car. So then we used to drive to the cottage.

While I was still living with my parents, we’d observe Jewish holidays, like before the war. After my wedding we’d go to my parents’ for holidays, in which my husband participated at first. But later he stopped associating with my parents, and so I’d take our son to my parents’ for holidays, as we’d all go to the Jewish community. After the February putsch, Chanukkah and Purim were celebrated at the Jewish community. When my father began working at the embassy, we began to celebrate holidays there. We had limited contacts with the community, so that our family wouldn’t harm the community, that they associated with Zionists. By then the times were very anti-Zionist. At Christmas we’d go to the mountains as well as at Easter.

Though raised in Jewish traditions, my son is a convinced atheist, and doesn’t distinguish between Jewish and non-Jewish friends. But his 16-year-old daughter, my granddaughter, is interested in things related to Judaism and the Holocaust. Daniel graduated from Czech Technical University; he works in his field and devotes himself exclusively to technology.

August 1968 26 was a huge shock for me. Prior to that there had been this relaxed atmosphere, and one had all sorts of hopes. I remember that we were at home, and at around 3am my husband’s friend called. I said to him on the phone, ‘Are you crazy?! Why are you calling at this hour?’ And he answered, ‘Open your window and listen!’ From the nearby airport you could hear the roar of planes landing. ‘That’s the Russians landing, and they’re occupying us!’

Right at that time we had some distant relatives from America visiting, so we were trying to figure out how to get them away. And my parents were living in Vinohrady, just a little up from the Czech Radio building 27, where there was shooting going on at that time. Luckily the phones worked, so we told my parents to come to our place. Back then my husband didn’t even protest, and my parents stayed with us for about three days, until things in the city calmed down.

I remember an anecdote from that time with my son, who was attending a kindergarten that was right next to our yard on Na Vetrniku Street. In September, after the Soviet occupation, he came home from kindergarten and my mother-in-law, his grandmother, said, ‘I noticed when those helicopters were flying around here, you and your friends were looking at them; boys like machines, don’t they?’ To which Daniel said, ‘But Grandma, we weren’t looking at them, we were spitting at them!’ He was just five at the time, and already knew very well what was going on.

Before the armed invasion, we’d had my Uncle Jiri from England over for a visit, and after the August occupation he invited us to come visit him. We really did take it as just an invitation, and so left Daniel with my parents and went there. My uncle was surprised that we hadn’t all come, because he’d meant his invitation as for emigration. But they’d only let us go because we’d left our child here anyways. I also couldn’t imagine leaving my parents. Plus my husband was after all older, didn’t know languages too much, and wasn’t capable of starting over somewhere else. And as far as emigration goes, I always thought only of Israel, and that wouldn’t have been something for him.

In 1967 Czechoslovakia severed diplomatic relations with Israel. The embassy staff had to leave the country within several days. So back then my father actually ended up responsible for the entire embassy, which back then was on Vorsilska Street, and was given the task of packing everything up and sending it off via the Swedish embassy. Whatever they didn’t want, he was to sell and then give them the money. My father took care of this for another several months, until the end of 1967. Then he went into retirement, and 14 days later he had a major heart attack.

When my mother died in 1985, I moved to my father’s place in Vinohrady for some time, to help him to start fending for himself. My father then began having problems with his heart, and at night had breathlessness, and was afraid to be at home alone. So I stayed with him. My son was already grown up, and so I’d return home only for a few days at a time, to cook some food and put the household in order. My husband died in 1992 at the age of 70, in Prague.

Right after the war, along with Rutka Bondyova and Zeev Scheck, my father got involved in a documentary effort, which I think was financed by the American Joint 28. After the war, the [Jewish] community was a go-between for humanitarian relief from Joint. We were getting things like clothes, blankets and similar things. We had come from the camps with basically no clothes, and the help of the Joint was very important. When there was an anniversary of the Joint a few years ago, I put on a sweater that I’d been issued immediately after the war, and it got a big response. They’d for example found a part of the notorious documentary film on Terezin, where they showed how Hitler had given the Jews a town. They got a lot of documents from the former Office for the Expulsion of Jews.

My father had concerned himself with these things for years, but when he retired in 1967, he began to be very active in this direction, and utilized various methods of smuggling these materials out during Communist times to Beit Terezin at Givat Chaym in Israel. He and Zeev Scheck were the main suppliers of material for this museum, and my father actually illegally delivered hundreds of documents, photographs and individual objects to Givat Chaym. Beit Terezin published an informational bulletin, and it was arranged that in it they’d always confirm the receipt of the documents. So for example a message would appear in it ‘From an unknown donor, we received documents No. 120 – 175.’

In 1958, an organization named ‘Aktion Sühnezeichen’ was created in Germany, which was composed mainly of young people from Protestant circles, who knew that what had been committed couldn’t be undone, but they tried to at least help and once again revive post-war Jewish life. So they’d travel to summer camps in Israel, in Poland, and in various other countries to visit Holocaust survivors, to help them. They also repaired cemeteries and synagogues. My parents would go visit them in Germany at their summer work camps, and would give lectures on the Holocaust, Jewry and Terezin.

My parents were actually among the first Czech Jews who were willing to communicate with Germans like this. Another person who was similarly involved was Dr. Josef Bor. And when people would come to visit, my parents took the place of today’s Terezin Initiative and would go with individuals or groups to Terezin, perhaps ten or twenty times a month. There was no museum there yet, so they themselves would guide them around. Back then Terezin was basically just the Small Fortress 29 with its Communist resistance, and on the subject of Jews in Terezin, there was silence. After my parents died, I automatically inherited this activity.

Various Jewish holidays were observed in Terezin during the war in order to maintain Jewish traditions. And in 1943, for Tu bi-Shevat, the holiday of trees, the children from the ‘Jugendheim’ planted a little tree, and my mother was there for it. When after the war she’d be showing people around in Terezin, she’d always stop at that tree and tell the story of how her little pupils had planted it there, and that none of those children had survived.

One day my mother was showing Mark Talisman around Terezin. He’d come to Czechoslovakia with his children, and his daughter, who at that time was shortly before her bat mitzvah, was very captivated by the stories. A half year later, on the occasion of the bat mitzvah in America, she made a speech in which she focused on this tree, ‘etz chayim’ [tree of life]. It was a very nice and mature speech; the American, formerly German Jewish composer Hermann Berlinski wrote a cantata entitled ‘The Irma Lauscher Tree.’ [Berlinski, Herman (1910 – 2001): American composer of Jewish origin. Among his large-scale works is Etz Chayim (The Tree of Life), commissioned by Project Judaica for performance at the Smithsonian Institution.]

At the beginning of the 1990s, I participated in an event named ‘Brotherhood Week’ in Dresden. It took place in a Catholic church, and in the program I suddenly saw written: ‘The Irma Lauscher Tree, cantata.’ Surprised, I asked the local priest where it had come from, and he told me that there was nothing simpler, that I could speak with the author himself. He took me over to the composer, and I told him that I was the daughter of Irma Lauscher. Everyone embraced me fervently, and then the cantata played.

Once I was showing a group from the Canadian Joint around Terezin, and in the spirit of family tradition I stopped by the tree and said that I’d really like it if there was a descendant of the tree growing somewhere by the children’s home at Yad Vashem 30. They took a great liking to that idea, and right away they sent to Terezin a gardener from Israel specializing in dendrology. He grew some seedlings and one really was planted at Yad Vashem, and another was planted in Givat Chayim.

On the occasion of Terezin anniversary days in Givat Chayim, I spoke on the subject of how it had never stopped tormenting my mother that none of ‘her’ children had survived, and that I thought that my mother had been the last witness and contemporary of that planting. Suddenly Michal Beer spoke up: ‘I was there, I was one of the children who planted that tree, and after the war I was one of the children who replanted it by the crematorium.’ The tree had originally stood inside the ghetto, and after the war was replanted. At that time a small plaque had also been installed there, saying that the tree had been planted by Terezin children and that now it was under the patronage of the Prague Jewish community. The plaque is still there to this day.

I didn’t begin to involve myself more intensively in the Prague Jewish community until after 1969, when we as a family no longer presented a danger to it. Daniel was a small boy, and at the community they began to develop various activities, mainly for students – these were taken care of by Oto Heitlinger, but also for children – this was under the aegis of Artur Radvansky, who put together a group of children who at the time were of elementary school age, thus from 6 to 16. He began involving them in sports, taking them to the mountains and camps.

There were about 20 children in the group, and because some of them were still little, he wasn’t able to manage it alone. So he was looking for reinforcements, female if possible. He knew my mother, because his daughter was taking English lessons from her. He asked my mother if she didn’t know of anyone, and she suggested me. I liked this idea very much, and so I took it on, and from the winter of 1970 I was in charge of this group along with Mr. Radvansky.

On winter weekends we’d go to the mountains; in Spindleruv Mlyn in the Krkonose Mountains we had two small rooms rented out in one cottage. There we also spent all winter and spring vacations, and Easter. Then during the summer we’d set up a tent camp in a meadow a little ways away from Pacov. We always celebrated Jewish holidays, Purim, Chanukkah, Simchat Torah [Simchat Torah] and spoke to the children about Jewish traditions and history. We tried to provide the children with this combination of Scout and Jewish education. The community partially subsidized these activities.

Sometime in 1975, some authority at the state ecclesiastical office declared that the Jewish community was a religious organization, and that only a real rabbi or cantor was allowed to teach religion, so they forbade us from performing any educational activities. Then it was also said that we weren’t any sort of sports organization, se we weren’t allowed to put on any camps and sports events. So from the originally only Jewish children we expanded, added other children, and kept on going, now however under the auspices of the ROH.

The cultural commission, which I chaired, was also cancelled, the reason given was that we were a religious community and had no business concerning ourselves with culture. So the organization of the celebration of holidays, which had originally been taken care of by the cultural commission, was moved into the cult department, which for long years was under Mr. Feuerlicht. And we kept on going...

At home we regularly listened to the Voice of America 31. I didn’t have much access to samizdat texts 32, until Charta 77 33. I didn’t sign it, but I did have its text, and lent it out to good friends. My husband was a big anti-Communist, but more of an internal one, he had participated in the struggle against Communists back as a student, and then no longer. In the fall of 1989 he of course also went to jingle keys [during the Velvet Revolution people symbolically expressed their dissatisfaction with the Communist regime by jingling their keys during demonstrations], those were great times, but for me very demanding.

On the one hand, I was experiencing great joy, but on the other great grief, from the loss of my father. My father died in Prague on 16th November 1989, thus the day before the revolution 34. He was already very ill, and if he’d lived to see the revolution, perhaps it would have injected some energy into his veins; as it was, you could see that he was very tired of the existing situation. On Tuesday he was going to the hospital for some sort of checkup, and as we were waiting for the ambulance, I asked him, ‘Listen, everywhere else around us, there are things happening. What do you think about here?’ He says, ‘It’ll still take a long time here, they’re these fossils here.’ That was on Tuesday. On Thursday he died, and on Friday, the 17th of November, the revolution started.

My mother and father visited Israel during the 1960s on business as employees of the embassy. I visited Israel for the first time in April 1989. The first time I went there for about 14 days with a small group from the Union of Anti-Fascist Fighters. The opportunity to travel freely, to see friends in the West, that was for me, personally, the greatest change that the revolution brought. Today I can say that all the hopes that we’d had back then hadn’t been fulfilled, that we’d imagined it a little differently. What I’m thinking of is that on a political level, Communism hadn’t been abolished. That great tolerance of ours opened the doors of the economy for former cadres, who held the reins and simply privatized it. Then these careerists in the former Communist Party simply just turned their coats and joined new parties. That disappoints me.