I, Lyudmila Samuilovna Matsina (before marriage - Levit),

was born on December 24, 1932 in Leningrad.

My parents lived in the 2-nd Sovetskaya Street then, where as early as in 1924

the family of my grandmother and her sister Vera with children settled.

The times, certainly, were difficult, but I, beeing a child, certainly didn’t feel it,

as I was a sole child who survived (before me Mum had two babies, the first was born dead

and the second girl died at the age of six months). Everyone was nursing me, and you could tell everything was done for me.

Grandmother was staying at home, and there was a housemaid, too.

My family background

My grandfather on the mother’s side - Leib Meerovich Golshmid [the correct spelling is Golshmid, according to the documents. Most probably, the original surname Goldshmidt was changed in the course of time], - was born in the Ukraine in 1872, in the town of Smele, or Shpole, because he is registered in Mum’s birth certificate as "Shpole resident". His family was rather well-to-do. Grandmother Rachel Moiseevna Golshmid (nee Eiderman) was also born somewhere in the Ukraine in 1881. Then it was Kiev province, and now it is the Poltava region. The parents proposed them to each other, before that they hadn’t met. As it was customary in Jewish communities back then, they were proposed to each other, but I am unaware about the details. But when they got acquainted, they fell in love with each other from the first sight and lived happily all their life. Grandmother died in 1944, in evacuation, grandfather - in 1947. I haven’t been to Shpole, I only now about this Jewish settlement from my mother’s birth certificate. I only know that her father was a Shpole resident – nothing else, unfortunately.

They arrived to live in St. Petersburg in 1904. But the first to come here was my grandmother’s father. He was registered as a merchant of the second guild. I found it out in the directory " All Petrograd " for 1915. At first Grandfather worked in the Kalashnikov stock exchange, near the Lavra. He was an expert in flour. As a commercial traveler (or commission agent – that is what written in the directory) he bought and sold flour, traveling extensively. And my grandmother, naturally, was a housewife. Then grandfather served in St. Petersburg as an assistant of the manager of Bligken-Robinson confectionery factory, where the managerial position was held by the husband of grandmother’s elder sister Vera. All of them together lived in Vozdvizhenskaya Street (nowadays Tyushin Street), not far from Obvodny Channel. They had rather a large apartment there. The family was well-provided for. During the elections before 1917, - as grandmother told me - they voted for the party of Constitutional Democrats (what kind of party it was?)… Before the revolution they used to go for vacations to Dubelnya near Riga (now the place is called Dublty), then - to the village of Martyshkino in the vicinity of St. Petersburg. They hired maids. Children, while they were small, were basically taken care of by the nurse, later – by a governess.

Grandfather and grandmother spoke basically Russian, but Yiddish they also knew well and sometimes spoke this language too. Grandmother Rachel was a fashionable woman and wore beautiful dresses and jewelry. Of course she would not put on a kerchief or a wig. They were not especially religious. And they did not go to the synagogue on Saturdays, even on big holidays. But some traditions they did observe. I remember that grandmother never gave us milk after meat. Kashrut was an inherent feature of Grandfather’s and Grandmother’s everyday life. But, in other respects they were not religious people – Grandmother didn’t wear the wigs, nor did she attend to the synagogue or pray. Grandfather worked in the chocolate factory and I have no idea of his religious life.

The wife of Grandfather’s younger brother also had endured enormous hardships in her life. Her name was Eugenia, her last surname was Zolotareva [her last husband’s family name]. Mother’s uncle left her with a daughter, and a bit later, in 1930s, she married a German engineer, who worked in Leningrad under a contract. But when his contract was over, he left to his Fatherland, and she stayed here and in 1937 she was arrested. Above all, she was a teacher of the German language, and thus they charged her of being a German spy. I think it was in 1938, when Beria [People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs] let people out of prisons, she was released. I do not remember precisely, but I know that by 1941 she was free. And when the war began, she was immediately arrested again and put in the chamber for prisoners condemned to death penalty. But she was a very tough, strong-willed woman and got through all that, although her legs failed her [became paralyzed] there, in that prison camp, and she could not walk. This is what probably saved her life, because she was not able to do that terribly exhausting physical labor. They released her in 1946, and she came to us, to the 2nd Sovetskaya Street in a quilted jacket, looking awfully. And she was officially prohibited from coming to Leningrad, because those subjected to repressions were banned from living in metropolitan cities. She was hiding at our place. One late evening we heard a doorbell, and Aunt Zhenya seized her quilted jacket and rushed to the lavatory and locked the door from the inside – so that nobody could find her. Being a spiritually strong woman she later recovered, received a contract proposal and went somewhere to the North to work. She got married again there, and earned herself a good pension. She died a long time ago, too.

Grandmother’s brother David Moiseevich and his wife Eva Abramovna lost both their sons during the Great Patriotic War. Misha was killed in the fights over Nevskaya Dubrovka, though for a long time he was considered lost, his death was not really confirmed. Aunt Eva waited for him until her death. His elder brother Sasha was wounded at the front and died in hospital of wounds.

There was some craving for Ukraine left in Grandmother’s soul - she taught me Ukrainian songs, but she didn’t teach me Jewish songs for some reason. They seldom traveled to the Ukraine afterwards, only on short visits. My grandfather’s parents lived there. He was a manager of some business here, I don’t know precisely! When the revolution began, my mother’s parents - grandmother and grandfather - lived in Petrograd, but in 1918 famine began here. Therefore they left to the Ukraine to their relatives. I recollect Mum telling me, that when after the Petrograd starvation they found themselves in that family farm of their Ukrainian kin, they were simply astounded: geese, chicken, turkeys, cows … In the Ukraine in 1918-20 they survived through the onslaughts of Makhno and Petlura bandits, Denikin Army attacks and the related pogroms.

My grandfather’s younger brother Yasha Golshmid served in the imperial army and was killed in 1915, during the First World War, somewhere in the territory of Prussia and was buried in a Jewish cemetery.

Another younger brother of Grandfather, Nison Golshmid (but they always called him Nikolay Markovich) was a student of the Moscow conservatory and participated in operas as a supernumerary. He lived in Moscow both after the revolution and after the Great Patriotic War. He had not become a singer, because his wife would not permit him to do so, and he worked for a very long time in one and the same place – as a sales director for one factory. He died in the 1980s in Moscow. He had one daughter Victoria, who had graduated from a college of law and worked in the Supreme Court.

My grandfather’s elder brother (I do not know his name) emigrated to America in the 1920s. Grandfather had sisters as well, but I know nothing about them.

My mother Аida Leibovna Levit (nee Golshmid) was born in 1906 in St.Petersburg. Before revolution, in lower classes, she studied in the well-known female Stayuninskaya grammar school. She was telling me about that grammar school with delight, that there was good order and, by the way, no anti-Semitism ever existed. One of the subjects was the Law of God, and the Jews were allowed to skip those lessons. And in general there was no anti-Semitism in the attitudes of people with whom my grandmother and grandfather communicated. Anti-Semitism in their circle in general was considered a shame. A person who showed any sign of anti-Semitism, was simply announced a boycott. After the revolution, in 1924, Mum finished a school in Petrograd that was located in the building of the former 1-st grammar school for boys in Kabinetskaya Street (now Pravdy Street).

Mother and her cousin Abram Isaevich Zlobinsky entered the Leningrad University. But they both were dismissed from the university - as persons of bourgeois origin. Abram became a journalist, for a long time worked in "The Red Newspaper" and took a pseudonym Lukian Piterskoi. And mother entered the Leningrad Institute of Municipal Construction Engineers which was then referred to as LIIKS, and later it merged with the Institute of Civil Engineers.

Mum had two brothers. The elder, Semen Leibovich Golshmid, was born in 1902. During the Great Patriotic War he was severely wounded and lost his leg. He died in 1948 in Leningrad. Her second brother - Alexander, born in 1909, also was a participant of the Great Patriotic War, and received a heavy contusion in the fights in Nevskaya Dubrovka. After the war he worked as an engineer and designer. He died in 1980.

The name of my grandfather on father’s side was Berk Levit, and in everyday life they called him Boris Petrovich. He died in 1944 in the city of Minyar, Kuibyshev region. Grandmother’s name was Frida, her maiden name, I think, was Kunina – I can remember it somehow. She died in Leningrad in 1949. Unfortunately, I know almost nothing about them. Unfortunately I know almost nothing about this Grandfather, where he worked or what he did, because nobody informed me about that, and I myself was not interested while being small.

My Daddy Samuil Berkovich Levit was born in Simferopol in 1904. Their family was also rather rich - they owned a house, I think in Kanatnaya Street. As a boy Daddy, it seems, went to Cheder, but I do not know for sure. Then he studied in a vocational school, in the commercial department. In 1929 Daddy graduated from the Institute of Civil Engineers in Leningrad and was assigned to Murmansk, the city under construction then. Daddy was one of the first builders and designers of that city. But Mum fell ill with tuberculosis there, and they had to return to Leningrad. Mum got acquainted with Daddy during the students’ practical training session in Kronstadt and they got married in 1928. Parents didn’t tell me anything about their wedding, I don’t even have any photos of this event. Maybe there weren’t any wedding at all, they could have just register their marriage with state bodies or live in civil marriage.

Daddy’s elder sister Rachel worked in the Crimean Komsomol, was a very loyal Komsomol member, and consequently named my cousin, born in 1922, in honour of Inessa Armand [a prominent Bolshevik figure], and after the death of Lenin renamed her Lenina. The father of Inessa-Lenina was a writer by name Gorev. Before the war, they performed his play "On the banks of Neva" in Alexandrinsky Theatre in Leningrad. He died in the middle of the 1970s, and Aunt - in 1936, of cancer.

Also, Daddy had a sister Fenya, but what her occupation was, I do not know. Her husband Yosya worked at a defense factory, therefore they were evacuated to Sverdlovsk in 1941 and never came back to Leningrad any more.

Father’s sister Sonya named her son Rem – the abbreviation for "revolution, electrification, peace". Sonya also was an ardent Komsomol member, as well as her husband Nikandr (in general we called him Kolya), but actually he was Nikandr Kuzin. Uncle Kolya at that time was the chief of construction of Pre-Baltic Electric Power Station, deputy of the Supreme Council of Estonia, they lived in Narva, and died in Pushkin, when they were retired.

Daddy’s younger brother Abram, too, was an active Komsomol member. He was the Komsomol leader of the steel-casting shop in a factory. Then he worked as a deputy director of a large factory in Gatchina. He also died rather young, approximately in 1976.

Until 1941, all Daddy's relatives lived in Leningrad, but the war scattered them over to different places.

During the war

Before the war, our family lived rather well financially. Daddy worked as an engineer and architect in a design organization and, probably, earned good money. When the war began, we were in our summer residence in Sestroretsk, but returned to the city in a rush. Soon Daddy was enlisted in the army, and Mum was urgently sent to a business trip, and I stayed with my relatives. In the summer of 1942 Daddy came and took me to Udmurtia, the city of Izhevsk, where Mum was already waiting for me. We lived in the Tatar family, nobody spoke Russian, except for the elder daughter. There was no furniture in this log hut - pillows and blankets were just piled up in the corner and were picked up for the night. We slept in our clothes, without any linen … Mum and me lived in a narrow room, separated from the landlord’s room with a partition not reaching the ceiling, the light bulb was only in master's "half".

The level of life in evacuation was extremely low, Mum was sick with tuberculosis, but all the same worked somewhere and received some trifling compensation. Actually we lived on father’s certificate and had some vegetables from our kitchen garden, which we planted. In the autumn of 1943, when Oryol and Smolensk were liberated, Daddy was sent there for mine clearing operations - he first studied the craft at some courses and trained soldiers later. In February 1944 we joined him in the town of Lyudinovo. We lived in a semi-destroyed house, which Daddy restored somehow with the help of his soldiers. Everyone wondered how we could live in it. Then we followed Daddy to the town of Kirovsk of the Kaluga region.

Now, let me tell you a little about how the life of some of our relatives worked out. Mother’s cousin - Aunt Polya Zlobinskaya, with whom they lived together in their childhood in Leningrad in the apartment in the 2-nd Sovetskaya Street, had suffered severe ordeals during the war. She married Yakov Bronshtein in 1930 or a little later. His father was a doctor, and he later moved to live in Kislovodsk, where he became the chief doctor of the Kislovodsk sanatorium. On June 7, 1941 Aunt Polya gave birth to a daughter, and their son was five years old by that time. When the war began, her husband decided to send his wife together with his two kids and a nurse, to his father in Kislovodsk – as far as possible from the war. But as you know, in 1942 the Germans broke through to the Caucasus and seized all the Caucasian area, the entire region. They issued an order for all Jews to come to a certain place with their belongings. But Aunt Polya said that she wouldn’t go there with her children. Her father-in-law started assuring her, that Germans were not brutal beasts, that he finished a medical faculty in Germany and perfectly knew Germans and did not believe in all those ball yarns about Germans. He and his wife, as well as his younger daughter and others - the family was quite large - all set off to this assembly point, and, of course, everyone was shot. And Aunt Polya started to roam round and about because they couldn’t stay in one place, for the neighbours knew that they were from Bronshtein family, and could report to the German authorities. So she kept rambling from town to town, leaving her children with the nurse, a Russian, Marusya by name, who gave out the kids either for her own children, or for her nephews. Aunt Polya went rambling from place to place, from Essentuki to Pyatigorsk, from Pyatigorsk to Essentuki and back, because otherwise she would have to check in in the German Commandant's office. She gave herself out for an Armenian woman, wore only black clothes, wrapped with a kerchief up to her very eyes. And once an elderly German on a horse cart overtook her on the road. He looked at her and asked: "Sie sind Jude?". " Nein! Nein!" - Aunt Polya uttered. And he said “OK” and brought her to Essentuki …to the Commandant's office, because she even had no place to spend the night. From Commandant's office she was sent somewhere to spend the night. In general, that’s how they stayed alive. Thanks to the nurse, her children survived, too. But after the war, when my aunt returned to Leningrad, she couldn’t find a job, because those who had been on the occupied territories, wouldn’t be hired anywhere.

After the war

Mum and me returned to Leningrad in August 1945, and Daddy still stayed in army, he was demobilized in 1946. During the war I continued to study, and at all schools I was an excellent pupil. But when we returned, Mum was given advice that I should proceed not in the 6th, but in the 5th form: "We know, how they teach in this evacuation!" But Mum persuaded them, and I didn’t lose one year because of the war. I continued to study at school 175 in the 2nd Sovetskaya Street, where before the war I managed to finish the first year. At our school nobody was in the slightest degree interested, who was Russian and who was Jewish, however, the two of my nearest friends were Jewish. I finished school with a silver medal in 1950. I had no special propensities to anything. And, following my father's path, I entered LISI - the Leningrad Institute of Construction Engineering. Those were the terrible years of 1952 and 1953. In those years, the last years of Stalin’s rule, there was an onslaught of anti-Semitism in the country. Jews were fired from work in enterprises and factories, they were banned from entering higher school institutions. Propaganda was claiming that Jews were the nation of “poisoners” – meaning the medical doctors from the notorious “Doctors’ Case”, fabricated by Stalin’s companions-in-arms in 1952. But in our students’ environment there wasn't a trace of anti-Semitism. But I remember, that when my relatives learned that Jews were going to be exiled, Mum burnt all the photos of our American relatives - Grandfather’s elder brother, who left for America in 1920s, and his letters, because everyone was scared of the worst. But nothing happened. God was merciful to us.

Marriage life

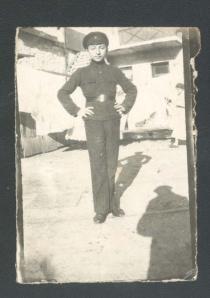

In 1955 I married Yuri Matsin. He, as well as I, entered LISI in 1950, the evening branch, and came to day-time lecture sometimes, participated in amateur art performances, but I had other company then, and we did not pay much attention to each other. And in 1954, when he returned after service in the fleet and continued studies, - from the second term of the first year, - we got really acquainted at some party, before November holidays, and in 1955 we were already a husband and wife.

The biography of my husband, as he puts it, is very "striped". He was born in Leningrad in 1931 - his father Zakhar Nikolaevich Matsin (Zakhary Nisonov) turned 54 then. My husband’s entire childhood was connected with theatre. When he was very small, his father – a graduate of the Saint Petersburg conservatory, took him to Mariinsky theatre, behind the scenes, and the first ballet that he saw was "The Nutcracker ". Later, during the war, in Perm, where the actors of Mariinsky theatre were evacuated, Yuri, as a boy, performed in children chorus of the theatre, sang in " The Queen of Spades " and in many other performances. At the end of the war he entered a choreographic school, but, unfortunately, or - fortunately, he felt that he had no calling for that profession, and shifted to a comprehensive school, after ending of which entered the Leningrad Institute of Construction Engineering. From the first year in the institute he was taken to the army – where he served four years in the Fleet. Then he graduated from LISI and became a mechanical engineer. And the life of an ordinary Soviet Jew with all the following consequences began.

He had encountered manifestations of anti-Semitism in the army, where he served in the most difficult years: from 1951 to 1954. He was the secretary of Komsomol organization of the ship, very active. And, from his words, the Deputy Commander on political education put much pressure on him, especially in 1954, when Yuri, being "a Komsomol figure", wanted to join the Communist Party. The Deputy Commander assured Yuri that he is never going to become a party member … And it was clear that reason was "a wrong nationality". A year earlier, when the so-called "Doctors’ affair" emerged, the sailors on the ship started to sing all sorts of anti-Semitic songs. Yuri expressed his discontent to the Deputy Commander, but the answer was that the guys were just fooling around, and no measures at all were taken.

Recent years

After graduation from the institute my husband tried several times to get a job in organizations that were considered "closed" [working on secret projects] - and each time he was rejected, in spite of the fact that he was a very well trained specialist. And later on, all his attempts to get an employment failed, - in 1961 he had been to almost all serious companies in the city. In the long last he acquired a position in a small firm

After graduation from the high school I spent much effort to try and stay in Leningrad: I was lucky that my husband still continued to study in the Institute. I went to work in the Institute of Refractories, worked there for about one year, but fell seriously ill and had to go to Essentuki for medical treatment. They wouldn’t give me a leave from work – I hadn’t worked enough by then yet, so they offered to discharge me, and promised to take me back later. But they didn’t hire me again - the boss who promised it was gone by then. And that’s where my hardships began. I could not find a job for more than one year. It was in 1956, when some British-Egyptian conflict took place. I would come to this or that institute, and they would tell me that they need project engineers … And when I brought the filled questionnaire, they were telling me that the situation had changed, staff reduced, etc. In this way I had been to 5-6 organizations and everywhere I heard the same answer. I tried TEP, too ("Heat and Power Supply Projecting Company"), and also was given a questionnaire to fill in - and again the same standard answer. The director of that institute was father’s friend; Daddy called him, but he said: "There’s nothing I can do. Employment issues are the responsibility of the 1-st [security] department and personnel manager, and I can not speak up against them". The reason was completely clear to me.

At the long last, I managed to get a job in a design institute of the 2-nd category, where they paid the lowest salaries. It was located in Poltavskaya Street, in a basement, - conditions were awful. It was called "Giprocommunstroi" [State institute for projecting communal infrastructure]. They designed waterpipes and sewer stations there. The collective was good, and I learned a lot there, having worked until 1963. Then I had to leave because we moved to another location. In 1965 I started to work in "Giprospetsgaz" [State institute for projecting gas pipes and equipment] - my daddy worked there for many years as chief project engineer, and he helped me to get the job with much effort. In that design organization I worked until retirement.

In my life I have designed and built many objects. They include the Northern and Southern water supply stations in Leningrad, reservoirs, gas pipelines, in particular Leningrad - Vyborg - State border with Finland, gas pipeline Ukhta-Torzhok, various compressor stations

My parents lived in Pushkin from 1966. Daddy had to retire rather early to take care of the diseased mother. She died in 1970. And Daddy died in 1986, and during a few years before his death he went to the synagogue on holidays, though he had never been a religious person.

I have never been to Israel and I can’t possibly say anything about my attitude to this country. As for political parties, - I have never joined any of them.

[Lyudmila Samuilovna has a very weak health and it prevents her from communicating with many people. Traditionally, her husband and she annualy go to the cemetery where her parents are burried in the town of Pushkin not far from Saint Petersburg. The interior of their flat is quite typical of a family of Saint Petersburg intellectuals: lots of books, a piano, an old computer. The spouses have no children, but they are very fond of each other and grieve that they have no one to pass the little information they have about their ancestors.]