Erzsebet Radvaner

Budapest

Hungary

Interviewer: Eszter Andor and Dora Sardi

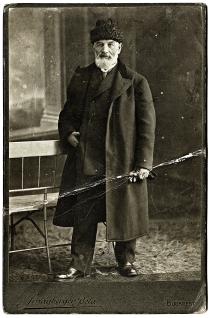

Herman Rosenberg, my paternal grandfather, was born sometime in the 1830s,

in Gonc, I think, and died in 1908 in the Jewish hospital in Budapest. His

wife was Regina Feuerstein. I do not know when she was born, but the age

difference between them was small and she died in 1908 too. They had eight

children: six boys and two girls. Three out of the six boys "magyarized,"

or changed their German surname for a Hungarian one. At the turn of the

century my father magyarized his name as well; he became Gonczi. I knew my

paternal grandparents, but as far as I know they were not very religiously

observant.

Ignac was the eldest son, born in 1852, and he was the only one who could

get an education. He became a lawyer, a legal adviser to the coal mining

industry in Petrozseny and the deputy of the town. He had a six-room flat

in Budapest; he was the rich man of the family. He died in 1920. He had

five children. Julia was the eldest. I think she died when she was three.

Imre lived in Petrozseny and in 1944 he was beaten to death by Iron Guard

men.

Judith suffered from heart disease and died in her thirties. Janos was a

student at the time of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919 and he joined

an anti-revolutionary group. We never knew about anything it. He got

married, had a daughter, and in 1932 when she was eighteen she died of so-

called children's paralysis. There was an epidemic of it then. After the

war came the Rakosi era and the communists; Janos said that this was not

what they had fought for, and killed himself. Ivan was left. He became a

foreign trader, got married and they had a mentally handicapped son. I do

not know when he died.

The younger brother of Ignac was Lajos. He was born sometime at the turn of

the century. He emigrated to America and corresponded with the family while

his parents were still alive, then he lost touch. The next is Miksa. He

remained Rosenberg. He was the vendor of a textile factory. He travelled to

Paris and I don't know where else. He got married in Vienna. Izidor was a

furniture merchant. He had a factory, but he lost it playing cards. Then he

married a woman who brought a lot of money to the marriage and managed to

save his factory. He never saw his wife before the wedding. My aunt spoke

French. They had two daughters and two sons.

Then there was Ida, who married Bertalan Szilagyi. They emigrated to the

States at the turn of the century and they had a son there, who died when

he was six. My aunt became ill and the doctor advised my uncle to bring his

wife home, if he did not want to bury her there soon. They came home. The

second son was born here in 1905. Bertalan had a successful ladies' fashion

workshop. Aunt Ida died in 1919. The younger sister of my father, Malvin

was born in 1879 and she died in 1932. She had a bad marriage. She married

in order for my father to be able to get married himself, and she had two

daughters. Both daughters were deported in 1944 and died.

The younger daughter's husband was a leather merchant and they had two

sons. They were very observant: they went to synagogue on Friday and

Saturday, but to save the boys they converted to Christianity. On Friday

they went to the synagogue to say goodbye to the Jewish God and on Sunday,

with a prayer book with the cross on it, they went to the Catholic Church.

There was a sort of monastery on Maria Street: the boys were educated

there. The priests who taught the boys hid them during the war. Thus they

were saved. They live in Switzerland.

Jozsef Klein, my maternal grandfather, was born in 1847 or 1848 in Szilagy

County. I think it was Hadad. He was a stove-maker. He came to Pest, but I

do not know when. He met my grandmother here, who was a widow then. She

brought two daughters into the family. I do not know anything of them; they

died. I don't know where grandmother Regina Bloch came from. There were a

lot of sisters and brothers. I can remember an aunt whom we visited. I have

only a few memories of Grandmother Regina; I was very young when she died

in 1913. Grandfather died in 1920.

There were four siblings in my mother's family. The eldest was Mor Klein,

who became Mor Karman. He worked in the stock market and in 1932, when the

market collapsed, he killed himself. His wife worked in the clothing shop

his mother owned. It was an elegant shop. People didn't go there to buy a

shirt, they went there to order a trousseau. They had a son, Istvan Karman.

He was taken away to a forced labor corps and he died there in Koszeg in

1944.

There is one more daughter. She lives in America. She got married in 1936.

Her husband was quite observant. They had the wedding in the Rumbach Street

synagogue. That one was more orthodox than the one on Dohany Street; they

had no organ there. Klari was not too observant as a matter of fact, but

she kept all the observances with her husband. In 1938 when the Anti-Jewish

law was discussed in Parliament, her husband said that he did not want to

be a second rate citizen anywhere. They emigrated to America, to New York.

Here at home they had had a child, but it died; there in America they had a

daughter. Mor's wife was in my flat, which was in a protected house, and

she emigrated to America in 1947.

The next brother of my mother was Artur. He did not like studying, he

wanted to be an actor. My grandfather did not like that and so he had to

study to be a locksmith, though later he was a traveller. He wandered all

through Europe from Moscow to Madrid. In the end he lived in Hamburg. He

rented a room at the house of a Christian dancer, who was fourteen years

his senior and had two grown daughters. He married her. If there was ever a

good marriage, then it was that one. When my grandmother died he came home

for the burial with his wife and a common-law son of theirs, who was the

same age as I was. One more son, Ferenc, was born to them in Pest in 1914.

They were living in the house where my grandmother's siblings lived. When

the child was born, the neighbours went and registered him as Ferenc Jozsef

Klein, religion Jewish. Grandfather took him into the stove trade. He

needed a locksmith for work with ovens. My grandfather had a workshop in a

cellar, in fact it was a storeroom, as they did not work there. They went

to houses and were told everywhere that only uncle Klein would do. Only he

was called to work at the Lukacs Cafe.

Artur was a soldier in WWI. When Feri was born, he was not at home.

Grandfather gave his wife money and the money my grandfather gave was

always just too little. When her husband came home she complained to him.

In 1919 my uncle started saying that his wife was better than his sister

was and they had an argument with Grandfather. Without so much as a

goodbye, he left his father and everybody else and they went back to

Hamburg. He became a projectionist at a Jewish cinema and his wages were

not too bad. His elder son joined the SS and did not speak to his father.

In 1939 my aunt came to Pest to certify that their younger son was a

Christian. She had a birth certificate that the child was Jewish, but from

the Evangelical minister she got a certificate that the child had been

christened. Later in the court she swore that her husband was not the

father of the child.

The elder son died as an SS soldier in 1940, the younger became a Wehrmacht

soldier at an anti-aircraft unit and died in a bomb attack. My uncle

survived the war; while he was at work, in the projection room in the

cinema, a child was killed in the neighbourhood and he was arrested as the

killer. Everybody at the cinema testified for him. He was released, but

there were no apologies. Instead he was taken to an internment camp, which

he survived. In 1958 he came home for the first time since 1919 and I think

he died in 1964.

Then there was Berta, she died in 1905 when she was 23 and engaged to be

married. She had some sort of heart problem.

My mother was the youngest. She was born in 1884 in Budapest. She finished

four secondary classes and after that she learned sewing and then she

stayed at home. My mother did not study, nor did her sister. They learned

sewing from an acquaintance, but women had no profession.

My father was called Mano Mihaly. He was born in 1877 in Gonc. His parents,

the Rosenbergs, had their own house and a shop. Then another Jew moved

there, one who was cleverer and more skilled than my grandfather, and they

went bankrupt. They moved to Kassa (Kosice in Slovakia today). I do not

know what they did there. Maybe the eldest son was already helping them.

Then they moved to Pest. They lived on Garai Street. There they were not

working. There was a shop there too, but that one was their daughter's. I

don't know if they helped out in the shop or not. Then they died. At

school, my father finished four upper classes. Then he went to be a shop

assistant in an elegant furniture shop and he was also a designer there. He

could draw beautifully. They had a very big shop on Kecskemeti Street

which sold very elegant furniture. The customers used to come and ask him

to have a look at the furniture they wanted to have. Then my father would

draw the furniture. He would draw the bedroom, the dining room, the living

room and the parlour. If it was suitable, the joiner made it, they

delivered it and installed it, and then the customer could move in.

Everyone in the joinery trade knew him.

There was a ballroom where the Royal Hotel is now. There was some ball to

which my mother went to dance and there was my father, not dancing. They

met there and love and marriage followed. Getting married was not so very

simple. My father was the youngest son and he had a younger sister, Malvin.

The parents said: "You can't get married before Malvin." They married

Malvin off, but she had a very bad marriage and it was always blamed on my

father. They, my parents, got married at last in 1904 in Pest, in the

synagogue on Dohany Street. My father was in WWI for less than a year,

because his boss brought him back. The boss had inherited the shop from his

father, but did not know the trade. Someone in the WarMinistry ordered a

suite of leather chairs and new furniture for a whole room to help

discharge my father. He stayed in office work until the end of the war and

was behind the counter in the mornings. Then the shop closed because it

went bankrupt.

My father was unemployed. I do not know too much about this period. I

didn't ask and they never told me. Under the Hungarian Soviet Republic my

father was working in a furniture depot. Then he was fired from that job.

He did lots of different things, he changed his trade nearly every month

until 1928. Then he was working in a shop that sold kitchen furniture. It

closed due to the Great Recession. He was unemployed for many long years,

but then he became shop manager in the Zsigmond Nagy & Partner furniture

shop.

My elder brother, Laszlo, was born in 1905. I was born in 1908. I went to

the primary school on Nyar Street. I was the best pupil the whole time I

was there. Then there was the Maria Terezia higher school for girls, on

Andrassy Street, which lasted for six years. It was very difficult to get

in there, as it was just for the rich. The husband of the sister of one of

my aunts was the director of a publishing house and he had connections to

all of Pest. My mother went to him and told him that she would like to get

me into the Andrassy Street School. He said that he could get me into any

school in the town, but not there: "She would only learn to show off there.

Put her into the middle school," he suggested. That school was on Nagydiofa

Street. I was the best pupil there too. Going to the synagogue on Fridays

was compulsory. At the beginning my mother took us to school, but later we

went on our own. There was no public transport. Laci went to the Realschule

on Realtanoda Street. I used to go along with them as far as Nagydiofa

Street.

For three years I learned to play the piano, because we had a borrowed one

from my uncle. During the year the piano was at our house, but during the

summer they moved out of the town to Zugliget and they took the piano

along. Then they said that all the transportation was damaging the piano

and they would not bring it anymore. I practised all kinds of sports, but

wasn't good at anything except rowing, which I loved. I swam, but badly. I

skated, I played field hockey and tennis, but all these just a bit.

When my father had no job our grandparents took them in because my maternal

grandfather was earning good money. It was meant to be until my father got

a job. I don't know how long it took my father to get himself a job. What I

can remember was the time he was a shop manager at the Fodor Company. We

lived first on Kiraly Street, then on Kertesz Street in a three-room flat.

There were two rooms with a balcony facing the street. There was a dining

room and a bedroom. All of us, the parents and the children, slept there.

The room looking out onto the yard was my maternal grandparents' room. We

moved there in November 1912 and grandmother died in April 1913.

My mother had no job but tending to the home. We had the same helper for

thirty years, Erzsi. She was sixteen when she came to us and she was very

decent. She cleaned the house and cooked; she was an excellent cook. As

long as my grandfather was alive, the household was kosher. My grandfather

was observant, heart and soul. Each Friday he went to synagogue and each

Saturday the same. Each morning he put on the tallit and the tefillin and

he prayed.

My father had some stomach disease. My mother bought ham for my father's

dinner, he ate it from the paper, and he did not use cutlery or anything

else. But he wiped his mouth after it. Grandfather took the napkin used by

my father and after dinner he put it in the laundry. Grandfather really

took it seriously. As long as my grandfather was alive, he sent us, each

Friday from September till January, a big goose bought at the goose seller.

Erzsi opened it. She knew well by then how to cook kosher. She salted it,

put it to soak and she prepared it in the kosher way, but it was my mother

who shared it out. I used to wonder, how she could share a roast goose

among such a big family. Many times on Saturday there was cholent, but

that was reheated. There was no cooking on Saturday, just reheating. Then

in 1919 there came the Hungarian Soviet Republic and there was nothing to

eat.

My father was working in the furniture depot. Under the Hungarian Soviet

Republic those who presented a wedding certificate saying that they were

newlyweds got free bedroom furniture. The peasants used to bring 5 kilos of

pork bacon and smoked ham; they believed that they would get better

furniture like that. So we ate it. Grandfather ate it too.

There were great Seders at Pesach led by my grandfather. There were lots of

us at the Seder Eve dinner: my mother's siblings were there , but none of

my father's relations. We had separate dishes for the Seder, we kept them

in the attic until Pesach. Before Pesach we used to give the whole house a

big clean. On the last morning, Grandfather gathered the last crumbs with a

candle onto a wooden spoon and burnt them and prayed. I stood at his side

because I immensely loved everything linked to a festival.

On the Eve of Rosh Hashanah we had dinner in the evening, went to the

synagogue, and then my father took us to his brother Izidor's place, who

had four children. That was all we did. That was where my father's family

was. We would always go there.

Laci (Lazslo) was Bar Mitzvahed and he prayed every morning for months,

because Grandfather wanted it that way. Then he said that he had no time

for it. My mother wanted us to fast on Yom Kippur. I did it in earnest; I

was religious. But Laci was not. I think he hid on Yom Kippur.

We were at Siofok down by Lake Balaton every summer until the beginning of

World War I. We rented a flat with a servant, and we packed up everything,

including all the kitchen stuff, and went there. When Laci went to school,

then we were there from the end of the school year until it started again.

On Saturday evenings the husbands came to visit. Then in 1914 my parents

went to Abbazia. The whole family went to Nagymaros together in 1918. There

was no holiday in 1919. Then we did not have holiday for quite a few years,

because my father was unemployed. Then the family holidays were over.

My social circle was mostly Jewish. I had very many boys around because

anybody could come to our house, boys and girls. My mother was the most

wonderful person in this world. We would go to the zoo every evening during

the summer, because there were classical music concerts on the Gundel

Terrace next to the zoo. Two brothers, who were our friends, had entrance

passes for the zoo and we all got in with that one pair of passes. All of

us got in separately at different gates, giving the passes to each other

through the rails of the fence. There were ten or fifteen of us. From the

age of fifteen I always went to concerts. Before that, Laci and I and two

cousins of ours went to the town theater every Sunday afternoon. You can

not name a singer or a conductor whom I did not hear. My father was not

interested in classical music. My mother liked it, but never went to

concerts. It was the hobby of my brother. My brother was a very cultivated

child. He was only interested in classical music. And he read and read.

There were not too many books at home, but we read books from the library

all the time. And we read everything: Gardonyi, Mikszath, Jokai, and so on,

all the greats of Hungarian literature.

Laci went to the Realschule. There he had his bachelors' exam, but he was

not accepted to the university because of the Numerus Clausus, a legal

limit on the numbers of Jews allowed into certain institutions and

professions. First he worked at my uncle's, in the office, then he had a

workshop for small furniture. He wasn't very successful. In the end he had

a good job. He was a manager on an estate somewhere in Szilagy County in

the territory Hungary took back in 1938. This was already during the war.

He earned good money there and he and his wife had two sons. My brother

converted to the Protestant faith. When his wife became pregnant he changed

his religion for her sake. Their son Adam was born as a Protestant.

My younger sister, Anna, was born in 1917. She attended the Jewish school.

She studied well, and had trouble only with Latin. In the fourth form her

teacher said that if my mother did not withdraw her from the school, he

would make her fail her year. My mother withdrew her. She went to

bookkeeping school for a year. Later she learned pottery and languages and

she was a shop assistant in a tea and coffee shop. She had to leave it

because of the Anti-Jewish law.

I would have liked to have gone to medical school to be a pediatrician, but

the Numerus Clausus was already in effect. So then first I learned hat-

making in a private shop. Then we were told that I should learn sewing, and

that there was always demand for that kind of work. I got into Julia

Fisher, which was one of the biggest fashion salons in Pest. I was sixteen

when I got there. Once, at the end of the workday, one of the seamstresses

told me to take some letter to some place. I told her that I could not. The

next day the lady in charge came and said that because I hadn't gone, I was

fired.

My uncle sent word that I should go to the Korstner sisters. I had a nice

time there and I learned the trade there. I got my certificate there one

and a half years later, and worked there for two more years, because I

needed two years' practice to get a permit to open my own workshop. Then I

quit. This was in 1929. For thirty years after that I worked and I had a

ladies' fashion shop.

At first I worked in my mother's flat. My mother had a sewing machine which

she had received from her family. My clientele was mostly Jewish and I had

a well to do ladies' fashion shop. Sometimes I had 8-10, sometimes only two

employees, it depended on the amount of work. I had no time during the week

because in the morning I had to distribute the work among the girls, and

then the clients started arriving to buy or to try on. I had this ladies'

fashion shop until 1949.

My first husband was Tibor Grosz. He was fourteen years my senior. We had

no wedding at the synagogue. He was not non-religious, but he said that it

was nobody's business what two people did. Once we went to the synagogue on

Dohany Street at Yom Kippur. Even then I was disturbed by all the talking

going on. I go there either to pray or to discuss things. I never felt like

going.

He was a chemical engineer. First he was in the leather factory. It went

bankrupt. Then for a year he was unemployed and then he became the head of

the laboratory of the Leipziger Spirit factory. We lived in Obuda. We had

no phone, and after 11 at night there were no trams. Our guests had to walk

to Budapest from there and everybody left at one or two o'clock in the

morning, because they felt so good. In our flat we didn't talk about

politics. Then came that particular Friday evening. We were leaving my

mother-in-law's place and people were shouting that Vienna was under

attack. With that, politics came. We moved to Katona Jozsef Street in 1938.

During the war, 32 people lived in my three-room flat. Our house became a

protected house. In October 1944, all the Jewish women between the ages of

16 and 40 were called up to the Kisosz stadium. We went from there to

Mogyorod, and from Mogyorod to Isaszeg. We were told that we were being

taken to work. We were in Isaszeg for two days. There was a French break-

through and we were herded backwards. We were brought back to the brick

factory on Becsi Street, where we spent the night. In the morning we

started walking towards Hegyeshalom. From there we went on towards

Zurendorf, Austria. There the SS took over. They were mere boys of 14-15,

at least they looked that way to me.

They made us get into railway carts and in the evening the train set off.

We looked out in the morning to see where we were. It was some town.

Suddenly I shouted that we were in Hungary. The train stopped in Harka-

Kophaza, where we got off. We got to Kophaza on foot, where we had to dig

ditches. There were no SS around, as they were trying to run away by then.

Usually we were guarded by self-trained peasants, but there were still some

SS, of course. There were four of us together. My younger sister, a girl

from the house and an acquaintance of my sister.

At the end of March the Russians were already coming and they started

herding us away, but we went back to Kophaza. We went to the Jewish

canteen. There the Jews who were in forced labour gangs got some sort of a

soup that had some beans in it, and in the morning some black liquid that

was at least wet and warm. There was not even water and we suffered from

thirst all the time. Anna was very clever and resourceful. She went to the

local authorities and told them that we were left there at the Jewish

kitchen, but we had nothing to cook. It was announced in the village that

food was needed at the Jewish canteen. Suddenly the boys saw that on the

other side of the road, the German soldiers were loading food on cars. They

were stealing bread and artificial honey and artificial butter. Then we

heard sounds of the cars. I said that I thought the Germans were leaving

and there were no Germans at all in the village. Then the shooting and the

cannon fire started. We set out for home all the same: by train, by cart,

on foot. We got home on the 11th of April. My husband died in Bozsok in

February 1945. He was above the age limit, which was why he was not taken

to forced labour earlier. In 1944 on the 20th of October, the Nyilas men

(Hungarian fascists) came at five in the morning, they gathered all the

middle aged men who could still walk and deported them. I never saw him

again. We were taken on the 23rd of October.

My mother and my father were hiding, holding Christian papers. Those were

real papers, not fakes. A teacher couple, Lajos Kovacs and his wife, had

run away from Hajduszoboszlo. It was not difficult to learn the name of the

man, but the woman was called Julianna Oblidalovics. My father was not

deported. The housekeepers were decent people, because when the Nyilas men

came, they hid him in a wardrobe or in the lichthof (a shaft in the middle

of certain buildings that lets in light and air). There was a mezzanine

with a door to the lichthof. The key to that was in the pocket of the lady

caretaker. The Nyilas men walked around the flat, he was nowhere. "And this

door?" they asked. "This is just the lichthof," she replied.

My father went back to work right after the war, to the Zsigmond Nagy and

Partner furniture shop. He had to furnish a guesthouse in Matrahaza in July

1945. (Matrahaza was a fashionable mountain holiday village and still is

today.) They came to take him there, though he was he felt unwell.

Something was wrong with his stomach, but he went all the same. This

happened on a Saturday. On Tuesday he became ill and was immediately taken

to Gyongyos Hospital. His diagnoses was what they called Ukrainian

Diarrhoea, and there was nothing to be done. They sent us a telegram, and

my mother and I went there immediately. Four hours after our arrival he was

dead.

When he died I went with my mother to the community. The community had no

gravedigger, no rabbi, they had nothing. We wanted to take him to Pest.

They did not want to do it. It was the summer of 1945, there was no car and

they could not transport him by horse cart. If they took a bad horse, the

journey would have lasted for too long. If they took a good one, the

Russians would have taken it away. It was a really big deal, but I managed

to get a community member to organize the funeral the same day. He

succeeded in getting ten Jewish men who could pray together. Though it was

difficult during the summer of 1945, he succeeded. My father was buried in

accordance with the orthodox rites the very day after his death in

Gyongyos.

My brother was at death's door. He was in a forced labour corps in the

summer of 1944 when the carpet bombing of the Ferihegy airport happened.

One friend of his died on his right, another died on his left. Laci had his

trousers full of holes, like a sieve, but nothing happened to him. Laci ran

away. They lived in the Szilagyi alley with fake papers. My brother lived

as Sandor Vajk, my sister-in-law as Laszlone Gonczi. Her husband was

deported and she did not know where he was. On the 1st of January, 1945,

Laci's father-in-law had been wounded and he was taking bandages to him. He

had some notes in his pocket on which he had written several Russian words.

What probably happened is that he was reaching in his pocket for the notes,

and they did not know why was he doing so, and shot him. My sister-in-law

knew where her father was. She went there and he found Laci dead in the

snow. My sister-in-law buried him there in the Szilagyi Erzsebet alley.

After the war, My sister-in-law, together with her two sons, emigrated to

Sweden.

I worked at an ambassador's place for half of a year in 1949, but could not

earn anything there. Anna was in the Communist Party school and she had to

attend evening school too. She became a foreign trader. She made business

deals, and learned German and English. I was taken into the Communist

Party, though I did not want it. Then I worked at the Agricultural Ministry

in the Filaxia, a veterinary pharmacy. I got to the personnel department in

1950. The Filaxia was the most anti-Semitic company ever. I was told that

in the 1940s a friend of the director brought a christianised Jewish woman

there. Her colleagues found out that she was of Jewish origin and they said

that it was either one way or the other: either the woman was sent away or

they would not come to work anymore. They did not dare to tell it to my

face; they were all nice to me. There is nothing more base than the work I

was doing, where one has to build up a system of informants to spy on

others. Whenever I entered a room there was dead silence there. I never

knew a thing. I could never have asked for any kind of information. I did

not want to really. Each day I had to write an atmosphere report. I was

proud of the fact that nobody was fired while I did this work.

I married my second husband in 1948. He was a private merchant, and he

could trade with state companies. Then at the end he was a chief supervisor

in a cooperative. He went around to supervise the branches, but he came

home when he wanted. I was left in the flat in the Katona Jozsef Street and

we lived there. My daughter, Julia, was born in 1949.

When my father was on his deathbed I promised him that my mother would live

with me. In fact it was much easier for me like that, because Juli was six

months old when I had to give up my fashion shop and had to go to work.

They kept my baby for me. For twenty-one years, my work was such that I was

at home in the flat. So if my child cried, I could go to her in the other

room. My mother reared her from her age of six months. I had a domestic

helper. When I had my fashion shop it was cheaper to have one, than to do

the cooking and the cleaning in my own time. I got my job during the summer

and Emi, the domestic helper, said she would take Juli in. They went away

for two weeks that was the holiday due to Emi. I gave her an addressed card

for her to write each day. I could not have provided such things for her in

Pest in 1950; she got the first milk from the morning milking and every day

they killed a chicken to get the fresh liver into her soup.

Juli was head of the class in the gymnasium. She was accepted at her first

application to the Theater Academy. The next day I went to work very happy

and met our legal adviser, who told me, "You shouldn't be so happy. It is a

bumpy career, someone either is very successful in it, or not." I've

thought so many times. I am very sorry for Juli's actual life. She got her

diploma in 1971, and she was in the provinces. She got a contract in

Debrecen first. From there she went to other provincial towns. I retired

when Juli got her diploma.

We did not speak about religion at home after the war. My mother was

observant and Vili her husband was too. But I said that we could not

educate the child in two different ways. If she was told something at

school, we could not tell her any different. She didn't notice that the

dinner was different and at a different time. And in 1956, during the

revolution, the order came that beginning in September 1957, religious

education classes would be started. The ones who wanted their children to

attend had to sign for it. I did not want to, but Vili signed that she

should attend the Jewish religion classes. Juli accepted it without

knowing what it was.

Her next meeting with Jewish life was when a classmate of hers came to our

place to play. At that time biscuits were sent in colourful boxes by Jewish

organisations and the other girl liked them very much. My mother told her

that she could take them home if she wanted to. The girl replied that she

could not take them home, because then her parents would know that she had

been to a Jewish girl's house. My mother told her: "Forget about the boxes

then. Look, you can lie however you want at home, but don't come here

anymore." From then on, Juli knew that she was a Jew. We never spoke of it.

Then she noticed that there were matzoh dumplings. We did not keep Pesach,

but there were matzoh dumplings. There was the dinner after Yom Kippur, and

before that Vili fasted and prayed. I did not fast. I couldn't. My work

mates never asked me "Are you coming to have lunch?" except on Yom Kippur.

I worked on every Yom Kippur. Juli knew several things by then, but not too

much, and she didn't ask. Emotionally, she became a Jew at that time.

There was a great festival in the Erkel Theatre in 1948 when Israel came

into existence. I was there and I was very happy. But it never occurred to

me to emigrate . We wanted very much to go to Israel with Anna, but we

could not get passports from here. Towards the end of the 1970s, Anna found

out that visas were being issued in Vienna. The visa was not put into the

passport, but given on a separate sheet, which could be thrown away so that

the authorities wouldn't find out if someone went to Israel. We were making

preparations, but Anna was very ill. I said that we should wait until she

got better, but I knew she wouldn't. So we never made it there.