Stela Astrukova

Sofia

Bulgaria

Interviewer: Svetlana Avdala

Date of interview: March 2006

I do not know this woman, I see her now for the first time.

At first glance – very well-preserved, with delicate and even childlike features. We sit down and we start. In the beginning everything she says seems innocent, especially the parts about her childhood. A discreet smile appears on her lips when she goes back to her memories.

We have been working for three hours already – no signs of tiredness on her part. We start the Holocaust topic. Her face goes pale, her lips purse slightly, but her speech is as rhythmical as before. The facts follow each other like chopped wood.

Her thoughts are clear and focused, without decoration or lyrical deviation. After two more hours she is as unemotional as in the beginning. My respect for that woman is growing every single minute. I get quieter and quieter. I am thinking, 'Do her difficulties ever come to an end?'

As if I am watching some kind of a movie. I remember such movies from my childhood about heroic events from our newest history. Another type of films appeared after that – the so-called action movies.

There is shooting again, chases, torture, but everything seems like a game, they lack heroism, lack ideals, which...'...which...,' I add in the end of the conversation, 'overshadow the rational mind.''But without those ideals, we would not have sacrificed our lives,' she insists.'But do we have to sacrifice our lives? Isn't it more important for a man to be alive in order to keep on the path of life he has chosen?',

I ask.This is a dialogue between the generations or probably a clash of characters, I do not know, but all the people from that generation seem different from us. They were exposed to some other inner light and another type of meaning. Some people would say that they look 'old-fashioned' now, but I think that nowadays 'old-fashioned' is a nice word.

They speak slowly, with some kind of dignity, as if standing on a podium and talking to the masses. Ready to serve in the name of...Our generation doubts heroic actions, as well as everything else. We believe only in the things we can touch, achieve or use, but what kind of people are we? Lonely, headphones on our ears, staring into the screens, playing virtual action games.

My family background

We came with the big group Sephardi Jews from Spain in the end of the 15th - 16th century 1 2. My paternal and maternal ancestors settled directly into Sofia. I do not know anything about their material state. But I remember my grandparents.

My paternal grandfather's name was Yako Azarya Levi. He lived with us. That was the custom those days, the parents of the eldest son lived with his family. My father had a brother, whose name was Azarya Levi, but he died during World War I on the Dobrudzha Front 3.

I remember my grandfather very well. I can clearly picture him in my mind even now. I was around 12-13 years old when he died. He had a beard and mustache like the old Jews.

He dressed very neatly. Every Saturday he went to the synagogue with the tallit and the book. When he returned, my grandmother would be waiting for him with the mastika 4 and some eggs. During the week he went to work. He had primary education.

He had graduated a Jewish school and had a small shop for paints and ironware, in which he worked. He went to work in the morning and came back for lunch because all shops had a compulsory lunch break from one to three. So, he would come home, have lunch and have an hour's nap. Then he got up, my grandmother made him some coffee and he went back to work. When my grandfather died in 1936, my father took care of the shop.

My paternal grandmother and my mother got on very well. Everything at home was in order and they both were kind women. The men went to work, my grandmother cooked and helped with the housework and my mother washed the clothes and looked after the children. Later, when we built the new house, in which we all moved, my mother also worked as a seamstress from home in order to help repay the loan which we took to build the house.

I did not speak much with my grandfather because he was more aloof. I spoke mostly with my grandmother Niema. I remember her long hair reaching down to her feet, which never went gray. My grandmother was not educated. She taught me to knit, to sew, to clean the big pots.

Before she married my grandfather, she had been a housemaid. When our family gathered for dinner, my grandmother would cook and clean the dishes. There were no washing detergents at that time. The dishes were made of copper and tin-plated inside. She washed them with soap and sand until they shone.

We had a tap in the yard and behind the tap - a cherry tree. My grandmother would kneel in the yard, washing and my mother would scold her that she would injure her back in this way. My grandmother also taught me the religious canons, because my parents were atheists.

My grandmother's hair was really gorgeous. She would untie the braids and comb her hair with ivory combs. She often called me to comb her and I loved that. She put gas and water in a small dish [effective remedy to protect against lice]. When she got up in the mornings, she untied the braids and combed her hair.

Sometimes she had only one braid, but most often – two. On holidays, she wrapped them around her head. She also combed her hair when we went to have a bath. Every Friday my grandmother, my mother and I would go to the City Bath situated at the river on Slivnitsa Blvd and Pirotska Str. When it was cold, we bathed in a wooden tub in the kitchen at home. Then she would call for me to wash her back.

Probably my grandmother was a very beautiful woman for my grandfather to marry her without a dowry. [The typical Jewish dowry – ashugar, included the smallest details from the everyday life of a Jewish family.] I do not know much, but I know that my grandmother remained an orphan very young and married without a dowry, which was very rare at the time.

I also remember my maternal grandmother. Her name was Yafa Sabat Beni (1880-1953) I remember her very well, because I often visited her. She lived on 35 Sredna Gora Str. in a house built by my grandfather Mois Sabat Beni (1878 – 1908), which was later extended by my uncles when they got rich. I remember that it was a solid three-story house – every brother had his story.

My grandmother was not very tall, and a bit overweight, but very energetic. I remember her with gray hair done in a bun. She was always dressed in black because she was left a widow at 28 years of age. She kept the mourning clothes until her death. She loved reading. She would read fairy tales in French and translate them to me.

My grandmother was a housewife all her life and looked after her children but she was a very educated woman for her times. I do not know the origin or the material well-being of her parents, but most probably they were well-off, educated and progressive [i.e. intelligent] people, because they sent my grandmother to study at a French school, which was quite a progressive decision at the time.

But when she got 13-14 years old, they decided to marry her. My grandmother told me that while she was playing ball on the street one day, her parents called her in to introduce her to her parents-in-law and her future husband – Mois Sabat Beni (1878 – 1908), who was a little bit older than her, probably 2 years.

So, he was around 15-16 years old. She left school. She was in the sixth or seventh grade. They did not have children the first years of their marriage, because they themselves were still children. Then she started giving birth to one child every year – five in all. At 28 years of age she remained a widow, because my grandfather died of hernia in hospital.

Their eldest son is Leon (1897 – 1953). In 1898 my mother Matilda (1898 - 1964) was born, next was Meshulam (1899 – 1970), Zhak (1900 – 1980) and last was Vizurka (1902 – 1975).

After my grandfather died, my mother remained an orphan at ten years of age. She graduated the third primary grade and my grandmother to make ends meet sent the two eldest children to work. My mother started work in a carpet factory for Persian carpets on Pirotska Str. owned by a Bulgarian, whose name I do not know.

Leon became a shop assistant somewhere. My mother was a small child and had very tiny fingers. She was given the task to tie the knots of the carpets. In order to reach the upper part of the carpet, she had to use a chair mounted on a desk. One day Maria Luiza 5, the mother of King Boris III 6 went there to see how carpets were woven.

When she saw my mother, she started asking questions about her. When she was told that my mother had lost her father and has four more siblings, she decided to help the family by making a charity. She asked my mother about her name, but when she realized that my mother was a Jew, she turned her back on her and refused to do help her in any way.

My mother worked there for some time and then she went to some Bulgarian tailoring atelier and learned the craft there. Then she started sewing in the houses of the rich people in the town. My mother was very beautiful and had a lean figure. The son of the owner of one of the houses, in which she sewed, fell in love with her and they engaged.

He was a Jew from a very rich family and she was very poor, but he was sick of tuberculosis and his parents could not protest his choice. The engagement lasted nine months. He gave her as a gift a very beautiful small polished chest, made like a jewel, with small drawers and doors and incrustations. He left the engagement ring in one of the drawers.

Later my father did not want to see that chest, but my mother preserved it. The fiance died of tuberculosis when my mother was 18 years old. I do not know his name. He was rarely spoken of at home, because my father was jealous of him. My mother told me the story of their love when I found the chest she was keeping.

When he died, my mother could not overcome her grief for a long time. In the course of time she managed to earn enough money to live better, because the rich people paid her well. Her brother Leon was also successful and earned enough money to enroll in a trade high school.

During his studies my mother also helped him financially together with their other brother Meshulam, who also started working. When Leon graduated, he became an accountant and he and my mother started supporting Meshulam who also wanted to graduate the same school.

Only the youngest son Zhak did not want to study. He became a goldsmith and was sent to France to learn the craft. When my mother became 24 years old, she met my father through her brother Leon. My father had returned from Paris and his first decision was to call my mother's brother Leon to see him. My father and my mother liked each other very much. My father was also handsome. They fell in love and married without any dowry on my mother's part.

My father Morduhay Yako Levi (1896 – 1972) graduated high school and was mobilized as an infantryman at the front. A year after that he was captured during an attack. He said that it was the most horrible massacre that had taken place during World War I 7.

The soldiers ran with the bayonets forward and butchered each other. The battle happened somewhere in France, but I do not know where. My father was lightly injured and sent to a camp in Marseilles where he stayed until the end of the war from 1915 until 1918.

He learned there to do electrical engineering work and the French language, which he had studied in high school. When he left the camp, he remained to work in France, at first in Marseilles, then in Paris. He worked as an electrical engineer. He also made some big improvement on the mechanism of the electrical bulbs.

And since he knew no laws and he was not a very practical man – he was very honest and guileless – he took the originals to some electrical company to adopt them. They took his unpatented designs and they started using them without paying him anything. He was very disappointed with them. When he came back to Bulgaria, he brought his designs, but the bulbs had already been introduced. He decided to return to Bulgaria and marry a Bulgarian Jew.

After the marriage my parents left for Paris, because my father liked life there. They spent there 2-3 years, tried to make a living. They lived in an attic flat. My mother worked as a seamstress and my father as an electrical engineer, but they did not have regular incomes. When I was about to be born, they decided to return to Bulgaria.

A month after my birth, I was born on 24th March, on the 25th April the bombing of the St Nedelya Church took place 8. Arrests started, people became anxious. My father's parents who had lost their elder son in the war on the Dobrudzha Front insisted that the young family leave Bulgaria.

They also saw that my father had broader views not typical for the Bulgarian style of life. He was raised with the ideas of the French revolution, he saw no differences between the people – black or white, Jewish or Germans. He did not denounce the marriages between Bulgarians and Jews. He accepted people's mistakes lightly, not with the fanaticism present at the times.

My parents left for Palestine. They traveled by steamboat. I was one month old. Leon, my mother's elder brother, welcomed them there. He had been living there with his wife Simha for two years. She worked as a midwife and I do not remember what he did. My cousin Yafa was born in Palestine.

My uncle and aunt remained a little longer in Palestine but eventually returned, I do not know why, probably because of the harsh climate. My parents, however, did not manage to settle. My mother did not work, because she looked after me and my father could not find work as an engineer, because there was no construction at the time.

They lived in a wooden shed and slept on the floor. My mother said that one night she heard me moaning and got up to check on me. She saw that a snake – a boa – had wrapped itself around me and was suffocating me. She panicked and woke up my father.

A short while after that I got a very severe eye infection, probably because of the dirt and the miserable conditions. They returned to Bulgaria and lived in a small brick house together with my grandparents on Morava Str., present-day 75 Zheko Dimitrov Str.

- Growing up

I spent my early childhood there, until 1932-33 when my parents built the new house. Until then we had a garden and a yard around the small house. I remember that the house had no foundations and its floor was directly over the ground, covered with boards. We had electricity.

We had running water and toilet inside. But my parents did not like that because the sink was right next to the toilet. So, he made a toilet outside the house right next to it and we did not use the one inside. In 1932 – 33 we built the new house in the garden of the old one, facing the street. The old house remained in the yard.

We lived in the big house until our internment 9. After my parents died, I sold it. We had everything in the new house – a toilet and a bathroom. It had three storeys and a big kitchen, a large basement, an attic, a toilet and a bathroom. It was not lavishly furnished – we had beds with iron boards, which I thought were very old-fashioned, a three-door wardrobe, a cupboard in the kitchen, a radio.

In the kitchen we had a stove using coals. After 1936 we bought a new Pernik stove. My father had brought the French culture with him. The whole basement was full of his books from France and he turned the attic into a workshop.

We lived in Iuchbunar 10 where there were a lot of Jews, but our neighbors were mostly Bulgarians. The Jews lived on the land between Klementina Str., Pozitano Str., Tri Ushi Str., and we were on the side, on Morava Str. We got one very well with our neighbors.

When we moved to the new house with my grandmother Niema and my grandfather Yakov in 1933 – 34, we let out the old one so that we could pay our loan. My parents insisted that our tenants were Jews. Our tenants also let out one of the rooms. I remember that we got along very well with them.

The people in those days helped each other very much, probably because they were not so overburdened by possessions as nowadays. My mother sewed at home. The woman in the tenants' family worked in a chocolate factory. I remember that my mother lit stoves with charcoal in order to cook because electricity was expensive.

She took the food for the little girls, warmed it, laid the table for them and the sent them home. If one of the three housewives was sick, the others made soups for all the children. They were very united. My mother taught them housework, what to buy, how to sew, how to keep the house clean etc. After all, she was educated, she knew French and had lived in France.

My mother washed the clothes twice a week. On Friday after we took our baths, she washed the underwear. On Monday we changed our clothes and she washed the bed linen. The next Monday she would wash the bed linen of my grandmother. She changed them every 15 days. All bed sheets were starched and ironed.

They were starched with flour. Even nowadays I starch my sheets. Starching keeps bed linen clean for longer. You put to boil some water and when it is ready you pour in it flour, which had been mixed with cold water before that and salt. You stir until the mixture gets thick like cream. Then you filter it and place the sheets in.

The housewives competed whose house would be the cleanest and the tidiest. In the wardrobe my father's shirts were ironed and tied with a blue ribbon. My mother's underwear was tied with a pink ribbon. My mother did not allow us to put or take things out of the wardrobe, only she did that.

My mother knitted and sewed. She sewed curtains, bed covers and a table cover for the new house. I remember that our bedroom in the house was facing the street. Right in front of the street there was an electric lamp post. While we were sleeping, my mother was sewing using the light of the lamp post in order to save on electricity.

We did not have enough money and lived sparely because we paid back the loan we took for the house until we were interned. My mother would take the old clothes of our relatives, wash them, turn them back to front and saw them again. I was always neatly and cleanly dressed.

As I child one day I went out on the street and one of my friends showed me a gorgeous doll and asked me where my doll was. I did not know what to say because I had never had a doll or another toy and now it turned out that every child on our street had some. I came back home crying.

My mother said, 'Don't cry, I will make you a doll.' She was sewing a black satin apron and she cut from the cloth a doll, sewed it, embroidered eyes, a nose and hair with the sewing machine and gave it to me. The next day I showed my doll to the others. But they all said to me, 'What kind of doll is that?

There are no black dolls. People are white.' And they showed me their dolls. I returned home crying once again because my doll was black. But my mother always had an answer for me. 'Go out and tell that that you are the only one in the neighborhood who has a Negro doll. No one else has such a doll. They will surely envy you.' So did I and later black dolls appeared throughout the whole neighborhood.

My mother read a lot in Bulgarian and French. I remember her reading 'Robinson Crusoe', 'Homeless' by Hector Malot, ‘Huckleberry Finn' [by Marc Twain]. I learned to read and write in Bulgarian and French at an early age before I started school. Later I read books to my sister.

My mother got a very serious kidney infection in 1928-29 before she gave birth to my sister in 1930. She had to have an operation. That made our life very difficult, but I think her brothers helped us. They paid her her share of their father's house and we used that money to pay for the operation.

The people who were poor at that time had special documents and could go to free examinations at Alexandrovska Hospital. But my mother was in University Hospital. My father was a proud man and paid the whole treatment there. Professor Stanishev, the best surgeon in Bulgaria at that time took out one of her kidneys.

So, she lived a healthy life until she was 68 years old when she died of liver cancer. I remember her going to change her bandages. My father also took me to see her in the hospital. I was three years old. My mother was lying in a narrow long room with four beds. I had a big bunch of flowers.

The professor came to check on her and told me, 'Hey, girl, where are you going with that bunch of flowers?' 'To see mommy,' I said. 'And who is your mommy?' 'The woman in the corner'. My mother started crying when she saw me. Then she got better.

My sister Dora was born in 1930. In 1934 my paternal grandmother Niema died. In 1936 my sister caught diphtheria. My grandfather Yako was also sick and my mother was looking after him. (He died the same year – 1936.) I took care of my sister. I remember that her throat was aching the whole time, she was diagnosed late. Everyone thought it was a throat infection and they prescribed her some creams to be able to swallow more easily.

I fed her. I would try to feed her two or three spoons, but she did not want any. And since I loved sweets, I would eat the rest. My mother and uncle Zhak got also infected from my sister, but my father did not. Immunity. My sister died in the infections ward of Alexandrovska Hospital.

My mother was admitted to the hospital at Stochna Station – the District Hospital, in the infections ward. But she made it through the illness and so did my uncle. Later, I went to work in the same ward where my mother was.

When my grandparents died, we started to let out their room too. A woman named Sterka took it. She was the mother of Dragomir Asenov [the nickname of Zhak Nissim Melamed, a Bulgarian writer of Jewish origin born on 15th May 1926 in Mihaylovgrad. Playwright and author of novels, novelettes and short stories.

Died in 1981.]. She was a Serbian Jew, a widow with no relatives in Sofia. She had three children. Dragomir Asenov was in the Jewish orphanage in the beginning. He came back every Saturday and we were friends.

Her elder daughter, his sister, lived with her grandparents in the town of Ferdinand [present day Montana, named Mihaylovgrad during Socialist rule]. Later she also came to Sofia to live with her mother.

When my grandparents were alive, we spoke Ladino 11 at home. My grandmother could not speak a perfect Bulgarian. We observed all traditions. We had a patriarchal way of life. We all had lunch and dinner. On Friday we cooked for Saturday – Fritas di praz – leaks balls, potato balls, a hen with rice.

On Friday we all had a bath, changed our clothes and cleaned the house thoroughly. We did not cook on Saturday. A gypsy woman came to light our fire to warm the food.

My grandparents did not touch fire and did not allow my mother to light it too. [A common ritual during Sabbath. Jews were not allowed to light fire and a person who was not a Jew had to come and do that for them.]

We arranged the table for Friday night and had a formal dinner. That was observed until my grandparents were alive. We had special dishes for Pesach.

After the holiday they were washed and were not used until the next holiday. Before the holiday they were boiled in water with soda so that they would shine

Once a year, in the three weeks before Pesach my mother started the great cleaning. On the holiday the whole family gathered at Mazarovi family – the elder sister of my father. She had a big house with four or five rooms. She arranged a big table for all the relatives. I remember that I would always fall asleep while they were reading the Haggadah.

They put a handkerchief full of matzah and boyos on the back of each child. The handkerchiefs were embroidered with gold threads on the ends. In this way we symbolized the aliyah.

The prayer ended with the words: 'This year we are here, but may we celebrate the next in Jerusalem.' On Pesach we ate paschal foods. We ate boyos instead of bread for eight days.

On Yom Kippur we all did taanit. [A fasting obligatory for the healthy and not – for the sick, the children, the pregnant women and those breastfeeding.] We sniffed a quince with clove and went to the synagogue... Before [Yom] Kippur the whole family gathered in the evening and had a celebration. When the fasting ended, we always ate soup.

Then we read a prayer and the real dinner started, most often a hen with rice. On Chanukkah the first and the last night my father's kin gathered at home because of my grandparents who lived with us. My grandfather lit the first shammash.

[Editor's note: The interviewee makes a mistake – shammash is the ninth candle of the Chanukkah candlestick, with it one lights all the other eight candles.] All the children were eager to light their own candles. And we competed whose candle would burn out last. That depended on the amount of oil.

We also gathered on Frutas 12. The children received purses with fruit. On Purim we put on masks and went around the houses of the relatives. Every one gave us some stotinkas. After that we counted our money and bought something. We loved that holiday because it was fun.

When my grandparents died, we arranged for them a funeral in accordance with the Jewish ritual. We were in mourning. The relatives, parents, brothers, sisters, the wife and children of the diseased, sat on a black blanket on the ground. The synagogue gave small black round tables, who were comfortable for the people sitting to eat.

The more distant relatives brought food to the mourning people for seven days. It was also typical when arriving from the cemetery, to be served coffee by one of the neighbors. Then the women stayed at home, did not go to the cemetery and prepared the welcome of the men and the rabbi from the cemetery.

They put yellow cheese, white cheese, baked eggs and boiled pasta with black pepper, a little oil, lemon and crackers on the table. The rabbi came to the house to make wings – he cut the shirt and the underwear of the wife as a sign of mourning. The mourning people wore black clothes and observed the mourning for a year.

During the internment and after 9th September [1944] 13, since we lived together with other families, we could not observe that ritual. And although we, the children, observed Jewish rituals different from the Bulgarian ones, we did not feel different from the other children and had Bulgarian friends.

My mother had a natural healing talent. She would visit Bulgarians and Jews who did not feel well, put on cupping glasses on their backs and advised them what to do to get better. She also sewed for Bulgarian families. Very often they invited her at their houses on different occasions.

My Bulgarian classmates also visited me at home to help them with the lessons, because I had excellent marks at school. On the street we also played with the Bulgarian and Jewish children. I remember that a Bulgarian family lived near our house and the girl Violeta was my friend. They had a big mulberry tree and we all gathered, Bulgarians and Jews, to pick the fruit.

The first time I felt I was different from the others, was when King Simeon 14 was born. Then as a sign of royal charity, all students got their marks increased by one point and the best students in the classes received awards. I was a student at junior high school at that time. I had excellent marks in all subjects throughout all my school years.

We were invited to the school gym for the presentation of the awards. The headmaster opened the ceremony and I went to the first row ready to go and take my award. I went to the stage, waiting for the headmaster to say my name. There was some confusion among the teachers and students on the stage, I saw that the headmaster was also embarrassed and then he announced the name of a student whose father was an officer.

He had had two 'fours' [In the Bulgarian system 'two' is the lowest mark and 'six' is the highest.] the previous terms. I was shocked at first but that was only for a moment. I was below the stage, I held my head high and went out the side door. I did not cry. I went home. We lived very close to the school.

When my mother saw me, she hugged me and said, 'What is the matter, why are you crying?' I told her everything. 'But, girl, we are Jews. The award is for the Bulgarian heir to the throne. A Bulgarian child should receive it.' Then I realized I was different from the others.

We kept in touch with the Jewish community. Before I started going to the Bulgarian school, I went to a Jewish nursery for two or three months, but not for long because my parents were afraid that I would have to cross the street alone. That is why the enrolled me in a Bulgarian primary school and not in a Jewish one. In order to get to the Jewish school, I had to cross Klementina Str. on which tram No24 was traveling.

The Bulgarian primary school is where the Jewish school is now. There were only three Jewish girls in my class. My cousin Fani, daughter of uncle Leon came to study with me in the third primary grade in the Bulgarian school. Her mother died, she fell into a severe depression and my mother took her home. We studied together from then on. Our friends were mostly Bulgarians.

From the primary school I remember the 24th May parades 15. Fani and I played in the school orchestra. I played the bass tuba. We also had shows in the end of each school year. We organized exhibitions too. We had classes in embroidering for the girls and making things out of wood for the boys. For example, they made shelves for books or clocks. And we, the girls, sewed aprons, skirts, embroidered nightgowns. There were both girls and boys in the classes in the primary school

On the high holidays we were taken to the St Nikola Church in the park. I did not go to church, but I stayed during the classes in religion because it was interesting for me, although we, the Jews, were exempt from that class. They taught us the Bible. My father never restricted me.

He very seldom said no to me and my mother listened to my father. During the classes they read the prayer, but the making of the sign of the cross was not obligatory and I did not do it. They were like classes in history for me and I learned some things about the New Testament from them.

I have wonderful memories from my teachers. They loved their profession. When we were in the third primary grade one of the teachers took us on an excursion to Pernik [a city in Southwestern Bulgaria, 25 km from Sofia] by train. We went to the mines to see how coal is dug.

He must have had very progressive [here the word is used in the meaning of ‘leftist’] views because he made us learn the poem by [Hristo] Smirnenski 'Quarry Boy' 16. That was the first time I left Sofia. In my junior high school we also went on an excursion to Veliko Tarnovo [a city in North-Central Bulgaria, 195 km from Sofia]. .

I graduated the classic high school where we studied Latin and Greek, because I wanted to become a doctor. I was influenced by the movie on Robert Koch, a German physician who discovered the tuberculosis virus. The name of the movie was also 'Robert Koch'. I remember that his style of work, devotion and detailed investigation of the origin of the illness impressed me deeply.

From high school I remember our literature teacher Sakarova, sister of the great politician, the social-democrat [Nikola] Sakarov 17. She was a lean and tall, neatly-dressed woman. She loved her job and instilled that love in us. We all loved her very much.

She also taught us Greek mythology and Greek language. Had gone to Rome and showed us photos. I was much impressed by Laocoon. [Laocoön warned his fellow Trojans against the wooden horse presented to the city by the Greeks. He told them that it was a military trick by Odysseus.

Soon two large sea serpents came out from the sea where Laocoon and his sons were presenting a sacrifice to Poseidon. They strangled him and his sons. The famous statue was made by the Rhodian sculptors Hegesandros, Athenedoros and Polydoros around 175-150 BC.

Now it is in the Vatican museums]. I was much disturbed by this image, probably because of my mother’s story about the boa. I remember that at the time of the internment my cousin Fani Aronova and I took one of the most beautiful flowerpots and gave it to our teacher as a memory from us. She said nothing. She had progressive [i.e. leftist] ideas.

But one day when I was in the fifth high school grade (I was in the UYW 18 leadership of the high school), we disseminated leaflet throughout the school. She was deputy headmaster and she got very angry and started looking for the people who did it. I did not know if she found out that we did it or not, but she did not catch us.

On Sundays my parents and I went out on a walk to some of the parks and on our way home we went to a confectionery. My father bought us cakes, boza 19, ice cream. When we had no money, my mother would joke with my father in Spanish [Ladino], 'You bought me nothing on the way to the park and back.

Why should we bother going out at all?' My parents loved going to the theater and to the opera. My father told us a lot about the theater performances of Sarah Bernardt [1844-1923, a famous French actress] and a play by Victor Hugo he had seen. I remember that the famous singer Hristina Morfova 20 was singing in the 'Magic Flute' [by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart] and we went to see her.

I was around 8 or 9 years old. It was very interesting but I could not understand the plot. I started asking my father. He told me, 'You will see the 'Magic Flute' many times in your life, but only once will you have the chance to listen to Hristina Morfova. Remember that.' She played the part of the Night Queen and I still remember how she was lowered on the dark stage, all illuminated. She was very impressive, a tall, big woman with a scepter in hand...

We went to the cinema regularly – once a week. We went to the movies starring Shirley Temple and I loved her. She is the prodigy child. Although my parents were not rich and highly educated, they had a broad culture. My mother sang very well. Very often she would hum whole arias while cleaning and sewing.

She had a great memory for music and sang long before we had a radio at home. Her elder brother Leon also had such a memory, and so did Zhak who sang in the Tsadikov’s choir 21 in Bulgaria and in a choir in Israel. Leon played the guitar and mandolin. They were musical but did not have the opportunity to develop their talent.

My parents kept in touch with the Jewish community – they paid araha [a kind of a membership fee paid by the members of the community in the synagogue] and were members of the community, although they were atheists and did not go to the synagogue.

My mother was not able to take part in the women's organizations of the Jewish community, because she had much work to do and had no time. My father was not a member of any organizations or parties. He was against party membership because he thought that the aligning with one party or point of view led to sectarianism.

He had an open mind. He read a lot of different newspapers and compared information. Most often he bought 'Utro' [Morning] 22, 'Mir' [Peace] [newspaper published by the People's Party from 1894 until 1944. Became a daily in 1906. In 1920 became a newspaper of the People's Progressive Party. In 1923 it was published by ‘Mir’ joint-stock company], etc.

There were operettas in the town performed on the stage of Odeon Theater at the place of the Musical Theater. We did not go there very often and neither did we go much to the theater. Once we went on an excursion by cart. We were like the gypsies – the whole cart was full of children, relatives, baskets of food.

I think we were heading for Vladaya but I am not sure. I was an obedient child, but at that afternoon, when the horses were released to rest, I decided to mount one of them, he was startled and hurled me to the ground. I was hurt very badly. I remember that everyone panicked and my parents brought me back to town.

But there were no serious consequences from the fall. We went on excursions and picnics very rarely. During the holidays we stayed in Sofia. My mother made me help her with the housework. She had more clothes to sew during the Easter and the Christmas holidays and I had to help her.

I often had to sew the hems and I hated that. But my mother would say, 'You are a girl, you should know how to sew a blouse or a skirt.' And I would tell her, 'I will not become like you, sewing all day on the machine.' I never wanted to learn how to sew. When I finished junior high school with excellent marks, I wanted very much to continue studying although my mother thought it was unnecessary for a girl.

My father intervened. 'She will go to high school and that's it!' So, they enrolled me in the Second Girls' High School, which was private. It was in a number of buildings on Dunav Str. and Iskar Str. The fourth and fifth grade studied on Dunav Str.

A short distance along the street was another house where the sixth graders studied and on Iskar Str in a yellow building studied the higher grades. There were four Jewish girls in our class – Fani Avramova, Linka Natan, Beti Ashkenazi and I.

There were three tramlines in Sofia. Tram No4 passed along Klementina Str. and tram No3 passeed along Pirotska Str. Tram No5 went to Knyazhevo. The other means of transport were carts and carriages. The people living in a house next to ours had a carriage. One of the brothers who lived there was a cabman.

He would go to the station to wait for passengers. When he came back home from work we, the children, would wait for him on Opalchenska Str. and he would take us all home on the carriage. It was a lot of fun.

Another memory of the way Sofia looked then is from a later period when I was already a member of the UYW. I remember that the winter of 1941 was very cold. The temperatures in Sofia fell as low as -25, -26 degrees C. My friends from the UYW group and I decided that we should by all means buy tickets for 'Carmen' starring Ilka Popova 23.

At four o'clock in the morning and -25 degrees I queued in front of the National Theater in order to buy tickets when the booking office opened at eight o'clock. I was so cold that had no strength to get back home. My aunt Reyna, my father's sister, lived somewhere close and I visited her to get warm. My aunt put my feet in hot water and made me tea. I remember going back along Pirotska Str. and seeing stoves with charcoal placed outside so that people would warm themselves.

I became a UYW when I was 16 years old and it happened through the Jewish chitalishte 24. When I learned how to read, my father took me to the chitalishte because he was not able to buy me books. He showed me how to select my books. The first chitalishte was 'Hristo Botev', next to my school so I did not have to cross the street.

When I was second or third primary grade I became a member of another chitalishte – 'Emil Shekerdzhiiski' 25. It was on Klementina Str. between Sredna Gora Str. and Opalchenska Str. It had a number of names before 9th September – 'Aura', 'Shalom Aleyhem' 26, 'Bialik' 27 It also had a central office on Lege Str.

The librarian there was the famous Jewish writer Haim Benatov [writer, lived in Iuchbunar, author of the novel 'This long road...'] The librarian in the office on Klementina Str. was Elena Kehayova, a communist. She used her job in the chitalishte to introduce us to the UYW movement and its ideology.

The first UYW group was at the Jewish chitalishte. At first there were groups of sympathizers at the chitalishte. They were UYW groups. We became members of some of the groups as sympathizers. The first years there were educational groups.

We had meetings before which everyone had to read a book. That is why, I say that UYW educated us not only politically but also culturally. We read Erenburg, Gladkov, Pushkin, Lermontov 28, Tolstoy 29. We discussed their books at our meetings. We had literary debates in the form of trials.

For example, we debated whether it was right for Martin Eden to commit suicide [a character of the novel 'Martin Eden' by Jack London]. We also had discussions about love. Some of the members defended the position of Elena Kolontay [the first woman diplomat of Soviet Russia] on free love, the others were against. Most of us, the girls, were against.

- During the war

The anti-Semitic attitudes started around the 1940s. I remember the Legionaries [Bulgarian Legions] 30 and Branniks 31 on Klementina and Pirotska Str. and how they attacked the Jewish shops there [The Night of Broken Glass] 32

[Editor's Note: the interviewee is mistaken – no Branniks took part in that incident because their organization was founded in December 1940]. Then they wanted to attack the houses but the UYW organization consisting of both Bulgarians and Jews put up a resistance. We even had help from the Bulgarians from other quarters of the town.

While I was studying in the high school, I felt the negative attitude of the Legionaries and Brannik girls among us. They spoke loud enough for us to hear them and disseminated rumors that the Jews were the reasons for the troubles because they were rich and ruled the nation and their riches were accumulated in dishonest ways.

Their anti-Semitism was especially strong at Easter. Then they directly attacked us with the words that the Jews drank blood and if a child went missing, we were the first to be blamed to have killed him or her to drink the blood. We, the UYW members, gathered and decided to resist the Branniks by explaining the truth to the Bulgarians who were not against us yet. We used every opportunity to talk to them.

Then all Jewish property was confiscated 33. They started with the manufacturing plants. Then they closed the shops, the factories, the ateliers. My father also had a shop. At first, they forced him to take a Bulgarian partner, then they made him transfer everything to the Bulgarian.

They wanted to leave the Jews without any means of earning money. We were only allowed to practice some craft from our homes, like sewing or mending shoes. The Bulgarians were banned to employ Jews and the Jews were banned to take Bulgarian girls as maids. Those were difficult and hungry years for our family because we were still paying our loan.

My mother kept on sewing. Only the three of us were at home and my father continued to work as an electrical engineer going to the homes of his clients. He repaired stoves, but he did not have much work because there were not many electrical appliances then. He could not make the electrical wirings of new houses – that was not allowed.

Then we had to declare all our property. [In 1941 the Law for Protection of the Nation 34 was adopted and included a variety of documents on the real estate and movable property owned by Jews, including bank savings. Jews had to declare all their possessions within a month of the adoption of the law.]

No one was allowed to hide anything. Using these declarations, they came and confiscated what they wanted. We were left our new house, but they took the rent we received from the old one. They took our radio sets and gave all Jews pink ID cards. We were renamed during the Holocaust. My name Stela was changed to Ester.

My mother's name Matilda was changed to Mazal, but my father's name Morduhay was not changed 35. Then followed the curfew and the badges [yellow stars] 36. The Jews were allowed to live in the Jewish quarter only – between Hristo Botev Str., Klementina Str. and the river. A kind of a ghetto was forming there.

When the orders for internment arrived, we were given only 3 or 4 days before the day of leaving. Pirotska Str. turned into a kind of an open market. The people took out their belongings and sold them on the street. They needed money and they were not allowed to take more than 30 kg with them.

Villagers on carts arrived from the nearby villages and bought a lot of things at extremely low price. I remember that my mother took out the woolen mattresses for sale. I sold one of them for 5 levs – the price of one loaf of bread. My mother was sorry at first that I had sold it for so little but then dismissed it with the words, 'We lost everything, so a mattress is not such a big deal'.

Rumors were circulating that we would be sent to Germany to work there. My mother supposed that since I was young, I would be sent to work somewhere without them. I remember that we had some gold family jewels. She divided them into three parts – for her, for my father and for me and sewed them into the hems of our clothes.

In my winter coat she sewed a gold bracelet, a pair of earrings and a ring and told me, 'Sell these things only if you have nothing to eat.' Those jewels were not found during the arrests and searches later on and I had completely forgotten about them. But when I got home on 9th September, all my clothes had to be boiled in a big cauldron. My mother remembered the jewels and took them out.

We also had silver coins with the image of Boris I from 1942. My father also had a number of them. He took out the threshold board between the kitchen and the room, dug a hole in the ground and buried them in a metal box. After 9th September we found them there and by selling them we survived the first days after the Holocaust.

My parents did not know about my illegal UYW activity. We had a special way of distributing the leaflets so that the police would not find us. Usually we went out in couples – a boy and a girl. The girl would put her back against the wall and glue the poster on the wall behind her. Meanwhile the boy would lean above her as if they are kissing.

One evening my father followed me and saw me with a boy, while gluing a poster. The boy was leaning over me but we were not kissing. My father did not realize what we were doing so we must have been really good. When I went home, he beat me hard and shouted at me, 'Are you going to be a prostitute?' I did not explain to him the truth because that was our secret. My father gradually accepted the new ideas, saw what was happening to the Jews and to us. One event played a major part in his change of beliefs.

It was 1943 on the eve of 24th May [1943] 37. We had already received orders for the internment and a rumor spread among all Jews that Rabbi Daniel 38 would speak in the synagogue the next day. All Jews went to the synagogue to hear his words. According to police reports there were around 10 000 people in the synagogue.

The book 'We, the saved ones' by Haim Oliver [1918 – 1985, a writer, participant in the anti-fascist resistance] includes all police reports on that day. There was also an order to all UYW members to go and participate in the 24th May march. I went with my father who wanted to hear the words of Rabbi Daniel and to protect me.

Not because he supported our ideas. The whole Osogovo Street was full of people. So was the Jewish school because the school and the synagogue had the same yard. [Editor's Note: the interviewee is talking about the small synagogue, not the central one].

Rabbi Daniel sent a prayer to God to help us and then went out of the synagogue. We, the people in the synagogue, heard nothing, but then we were told that we should go on a protest march towards the castle because it was 24th May and everyone was supposed to be in the streets.

The students' march organized by the Bulgarian government started from the [St Kliment Ohridski] University 39. Usually the king watched the parade either in front of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral 40 or on the balcony of the Military Club 41. We were told that we would protest in front of the king against the internment of the Jews.

During all big national holidays the houses were decorated with national flags. The writer Dragomir Asenov and another boy took a flag, which was hanging from the fence of a house and led us marching. Initially we were a lot of people. On the corners of Osogovo and Klementina Streets the elder people would stop us with the words, 'What are you doing? You are getting us killed!'

But we marched forward and the rabbi also came with us. But when we started the protest demonstration not all the people came. Mostly the UYW members joined us – we were probably around 500 – 1000 people. Somewhere before Hristo Botev Blvd the police had found out about the protest and stopped us with mounted police.

The whole neighborhood was blocked for an hour. The police started beating everyone on their way. At that time I had two long braids. I wanted to fight the police with my bare hands. I was that stupid. Then I remember my father taking hold of me by the braids and taking me home.

With the whole neighborhood blocked, everyone out in the street was arrested and taken to the yard of the Fotinov school. The police started going from house to house and arresting every Jew they saw. The arrested women were released but the arrested men spent three days in the schoolyard. We went around the yard trying to give them something to eat but we were not allowed.

The police probably checked everyone in the records and all Jews whose relatives were political prisoners were sent to the Somovit camp 42 and the Kailuka camp 43.

The rest were released with the order to keep the deadlines in the internment orders. That was how the 24th May ended. The protest was very brave. Such a protest in the heart of the fascist power! Of course it cannot be compared to the Warsaw ghetto, but it was a great example of the Jewish resistance.

At the end of May and the beginning of June 1943 we were interned to the Jewish neighborhood in Gorna Dzhumaya [present-day Blagoevgrad, in South-West Bulgaria, 76 km from Sofia]. There were Turks, Macedonians and Bulgarians living in that town and they were all very tolerant and treated us well. I do not remember any anti-Semitic attitudes.

We even lived better than we did in Sofia where the Legionnaires raided the Jewish streets. We were not allowed to enter the Bulgarian part of Gorna Dzhumaya. We were forbidden to rent Bulgarian houses. In fact, we lived in some kind of a ghetto.

Our life during the internment was very difficult. We shared a house with Angel Vagenstein 44 who had been mobilized before the internment and worked in the construction of the railway Blagoevgrad – Simitli. At that time he had graduated a technical secondary school.

His family was also interned to Gorna Dzhumaya and lived in his room – his parents and his brother. The other room was occupied by another family. We did not have a room and lived in the corridor. There was a curtain above the beds made by the torn rucksacks so that we would have some privacy from the people passing through the corridor.

We were starving. There were some shops from which we could shop at certain times. We had rations but the Jewish rations were not the same as the Bulgarian ones. We mostly used the black market. The villagers from nearby sold us their produce. The first two months in Gorna Dzhumaya were calmer. But in June and August when the partisan movement gathered strength, the district police came and the situation got worse.

We were not allowed to work, but my father, who was an electrical technician, was hired by a communist who had an electrical workshop. His name was Tutev. He paid him the same salary he gave to the other employees and that helped us live a little bit better. That also helped my parents pay the lawyers and the expenses of my trial when I was arrested. We also used our savings and sold the jewelery and clothes. There was a curfew.

I was in the 12th grade and I was allowed to graduate high school in Gorna Dzhumaya. My father asked the authorities for permission and the regime was more liberal in its first months. Probably I was the only Jew who managed to graduate.

I enrolled in September. By the end of September I had to go underground. By the end of December all high schools were closed. After 9th September 1944 the school in Gorna Dzhumaya issued me a document that I had graduated their high school.

Despite the bad conditions we got our lives a bit organized. I immediately became a member of the UYW movement in Gorna Dzhumaya. Jacky [Angel] was in charge of the Jewish group and when he became a partisan and left in August 1943 I replaced him. We did a variety of activities there.

Every evening before the curfew, which started at 6 pm we gathered the young people at the synagogue and held lectures on popular topics. We, the communists used these lectures to familiarize them with our ideas. Each Jew, who had knowledge on a topic, could present a lecture. We finished 15 minutes before eight o'clock and since the neighborhood was small we had enough time to go back home before the curfew.

In the summer we organized the children – we divided them into three groups, each of which had a teacher, one of whom was I. We learned songs, folk dances and games. We took them out of the town near the large Bistritsa river which passed near the town.

When I went underground at the end of September I was replaced by Dr Reni Ashkenazi. Then they formed a Jewish school. The children were divided into classes according to their age and the Jews who had graduated high school taught them.

There was no entertainment in the town but the young people started gathering. We sang, danced like all young people. The elderly women gathered on kitas. I do not know what this word means, but what they did was the following. Four or five women gathered in a yard and knitted, sewed, talked and read newspapers.

We, the UYW members, also had a combat group. Our task was to disrupt the telephone lines of the German troops there. We prepared for attacks but we did not do them. We were taught how to fire a weapon or set off a bomb. We provided food to the partisans.

We collected food and clothes. One of the engineers who lived in the house made a radio set and we gave it to the partisans. We helped them in every way we could. The villagers also helped us a lot.

Our demise was caused by two factors. At the end of November 1943 in accordance with a decision of the Gorna Dzhumaya partisan team, Jacky, Mois Kalev and Liko Seliktar came to Sofia with fake IDs in order to rob a rich Armenian family and buy weapons for the team with the money.

The decision was taken by the team but when it reached the district committee of the party, they rejected it as unfair. But Jacky and the others had already left. A member of the leadership of the team met me and asked me to tell Jacky that the burglary was off and they had to come back immediately.

The meeting was on Sunday evening. I talked with Jacky's parents and we started looking for ways to reach him but could not think of anything because Jews were forbidden to travel. While we were wondering what to do, they did the burglary. Until recently there was a memory plate of Mois Kalev the Mouse there. He died during the action.

The other participants were Niko Seliktar, Ana Valnarova – guarding in front of the building, Jacky and Mois Kalev who went upstairs and broke into the flat. They demanded the money from the family. The daughter who was pregnant faked a fainting and Mois Kalev went to bring water from the kitchen.

Jacky remained with the family but suddenly the daughter jumped and started shouting from the window for help. At the same time a sergeant and a policeman were passing in front of the house. They ran towards it. Jacky and Mouse started running down. All partisans ran in different directions.

Jacky managed to escape but Mouse was surrounded and killed himself in order to escape arrest. Jacky went underground and stopped traveling. Yet, he was found and arrested at the end of 1943 because there were not many people in Sofia after the bombings and internments. That was one of the reasons for our demise.

At the same time there was another failure in our team. During some action in which Kiril Gramenov, Pesho Petrov and Nikola Parapunov, secretary of the district committee of the party [Bulgarian Communist Party up to 1990] 45, took part, there was a shooting, in which Nikola Parapunov was killed, Kiril Gramenov was wounded but managed to escape and Pesho was arrested. He gave the names of the leadership of the city committee of UYW in Gorna Dzhumaya and I was a member of that.

After those two events the secretary of the city committee of UYW was arrested along with a lot of people with whom I worked. The committee decided that I should go underground so that I would not be arrested. I started hiding in the houses. All people from the Jewish neighborhood sheltered me.

My illegal name was Dunya, because I had nice and long braids then. That was the name of the character in the movie 'Station Supervisor’ based on Pushkin’s novelette. They said I looked like the actress who played that part. Angel Vagenstein made up that nickname. And since no one looked for me for a long time, the committee decided that I was not betrayed and ordered me to come back and start school.

I was arrested on my first day at school. The interrogations were in the district police station in Gorna Dzhumaya. Fortunately, a lot of facts were already known before I was arrested. A policeman, whose name was Nedyalkov, always came to take us to the interrogation rooms and told us what was already discovered so that we would say it again and avoid torture. After 9th September he was arrested, but we stood up for him and he was not only released, but he was taken back to work.

After the torture, we were taken to the military barracks. The conditions there were very bad. I spent three months in detention in Gorna Dzhumaya and at the barracks. We were three girls – Slavka Kordova, Dobra Andonova and I. Besides the tortures, we were also subjected to humiliation.

There were only young men at the barracks. We had guards of course, who did not admit the boys to go near us, but they were also men. When they let us to go to the toilet in the mornings and in the evenings, we passed by the prisoners. All of them teased us and said terrible things. The walls of the men's toilets were low and the prisoners and the guards tried to peek it.

Tutev, my father's boss, was sent to our barracks to do some work and he told my father to come and see me. So, my father took out the yellow star, came to the prison and found us. He passed along our windows. I saw him and started crying. I felt so relieved. He did not dare stand in front of the windows but passed beside them as often as he could. I cried, he cried...

At the end of January and the beginning of February [1944] we were sent to 5th precinct in Sofia. It was hell. They searched us in the most humiliating way. We had to strip naked and they started searching our clothes. We stood there, naked and dirty because we had not had a shower in a very long time.

My last shower was on the 13th December and my next – on 9th September. We were put in a dark cell where the only light came from the cracks in the door. There were such big cockroaches that I have been afraid of them ever since. They were scuttling on the floor day and night... Hell! My parents did not know where I was.

They found out that we were no longer in Gorna Dzhumaya. While we were at the barracks, they regularly brought us food. My mother washed my clothes and sent them back. But when we came to Sofia no one knew where we were. There was one week when they gave us nothing to eat.

Suddenly the door was opened and a policeman came out. 'Hey, chifut 46, come and clean the stairs. Are you going to sleep all day?' He brought me to the kitchen. He made me fill a bucket with water and wash the stairs.

When I came back, he stood guard around me and when some policeman passed nearby, he started swearing at me. He brought me back to the kitchen to return the bucket. Meanwhile, the women in the kitchen had prepared some bread and yellow cheese for me. 'Eat, girl, eat!' But there was such a friendship and solidarity between me and the other girls that I said that the other girls were starving too.

So, the two women cut the bread in two and filled it with cheese, yellow cheese and butter. That was in the winter and I was wearing the winter coat in which my mother had sewn the gold rings, which no one managed to find. I hid the bread beneath it and the policeman took me back to the cell. After 9th September I did not manage to find these people. That bread, which we divided among ourselves in the cell saved us from death from starvation.

From the 5th Precinct we were sent to the Sofia prison. That happened on 22nd March. I remember that date because it was my birthday – the first day of spring. It was not so scary in the prison because there were no more tortures.

There was a female supervisor Konyarova, a die-hard fascist, who hated the Jews and sent me to the lock up room for the smallest things.

We were led out on a walk for an hour in the morning and one or two hours in the afternoon. We had no hot water and we used the beans soup to wash our hair. After all, it was mostly water with two or three beans.

The UYW organization was also present in the prison. One of our tasks was to bring to our side the criminal prisoners so that they would help us in contacting the outside world.

They were on a more lax regime – they were allowed to write letters and receive food from the outside. On afternoon I was sitting and singing a Katyusha song 'Apples and pears are blossoming', a famous Russian song. [The song is a symbol of the Russian army during WWII, because it is related to the Katyusha weapon and the turnover of the war after it started to be used.]

Then, a girl, about 19 or 20 years old, came to me. Her name was Katya. She had a one-year sentence because when she was a maid, she stole the satin corset of her mistress. She came to me and asked me, 'What are you singing about me?' She learned the song and started singing it from morning until night.

The prison was echoing from her strong voice and we all nicknamed her 'the cock-a-doodle-doo'. I also taught Katya a poem by my favorite poet Nikola Vaptsarov – 'A song of man' 47. She would go around by herself and recite the famous verse, 'But there in the prison he met honest people, became a real man!’ She was very fond of me.

We decided to organize a musical and literature performance on the occasion of 1st May [Labor Day] with songs and dances. We tried to keep our spirits up in prison. After the walk, we went back to our cells and without being noticed by the supervisor we gathered in one of the cells...

I had to play a dance accompanied by the rhythm of two clacking spoons. Konyarova found us, started shouting and did not allow anyone to go out of their cells for one week. And since she found me dancing, Sheli, another Jewish girl, singing and another girl clacking the spoons, she sent us to the lock up room.

It was dark and empty there with a bucket for a toilet. Three days passed on without any food or water. Konyarova lived in the prison and used Katya, 'the cock-a-doodle-doo', as a maid – to clean her room and wash her clothes.

While cleaning, she managed to steal the keys for the lock up room. She grabbed some food sent for the prisoners by their relatives and some clothes. She came downstairs, opened the door and threw everything in. But at that moment the alarm went off. Nobody knew that the lock up room was connected to it.

Konyarova came downstairs and saw Katya locking the door. She beat her in front of our eyes and locked her in the next lock up room. She opened our door and took everything back. In the fuss one of my friends managed to open the bucket and put the bread inside. After Konyarova left, she took it out and said, 'See, this piece on the top has not touched the bucket.' And since we had not eaten for four days, we ate it all. In fact, that saved our lives.

Around 5th May the great bombings took place in Sofia. The fences of the men's prison were taken down and we all we sent to the Pleven prison.

The trial was at the end of August. It took place in Gorna Dzhumaya. When we were taken to the courthouse, we passed along the streets – the men were wearing chains and the women – handcuffs. The people in the streets greeted us and threw flowers at us. The end of the war was near.

My lawyer was Cheshmedzhiev. I remember that he said, 'There is no point in sentencing them. In 20 days you will be forced to sit in their place.' When I came back to the prison, I brought a lot of illegal materials – newspapers, magazines.

Since I was underage, I was sentenced to ten years imprisonment for anti-fascist activities. There were two more Jewish girls in the Pleven prison – Sheli and Zizi, a schoolgirl from Pleven.

We, eleven or twelve women were locked in a single-person cell – two meters wide and 3.5 meters long. There were plank-beds in the women's prison and nothing at all in the men's one. In the evening we laid down, sideways, packed like sardines because there was not enough room to lie on our backs.

First, we lay on our left side, and then we all would turn on the right. There I caught tuberculosis because there was a sick woman in our cell. On the eve of the 7th September a Jewish boy who had been sentenced to death was taken out by the guards.

They said they would just interrogate him in order to avoid protests, but they never brought him back. Meanwhile, the people outside heard that something was happening in the prison. The Legionaries and the Branniks surrounded the prison to prevent the Russian army to storm it before the execution.

Our comrades in Pleven heard about that and made a blockade to protect us. They were on watch day and night. On 7th September [Konstantin] Muraviev 48 issued an order for the release of all political prisoners. But the director of our prison refused to let us go.

Then all of our comrades started to force the doors open. It looked like the storming of the Bastille. They brought some railway tracks and started smashing the doors. They opened them, came in and released us. Meanwhile the director notified the police and the doors had been forced open.

We were all coming out of the prison. At first the male prisoners forgot about the women and then came back to unlock us. Meanwhile, we caught Konyarova and took her keys. We rushed outside. Zizi, who had been released two months before, because she was acquitted at the trial, had mounted a door and when she saw me, she rushed to hug me.

We were chased by mounted police and we were being shot at. Some of us ran towards the grapevines. I went to my aunt's place with the three girls and four or five people from the prison. We went to the house of Meshulam Beni, a brother of my mother who lived with his wife Lora, his daughter Fani and my grandmother Yafa.

My cousin Fani Avramova was outside with the protesters. She took us there. Meshulam had been interned to Pleven and brought us food in the prison. Yet, the police managed to take a lot of people back to prison. On 7th September one of our saviors was killed in the shooting.

The next day Muraviev's order for the release of the political prisoners came and they had to obey. In the evening we took a train to Gorna Dzhumaya. On 9th September I heard the proclamation of the Fatherland Front 49 at 6 am at the station in Sofia. We traveled all night together with the political prisoners in a horse wagon on the eve of 9th September. We sang all the songs we knew – 'We will give hundreds of victims, but we will beat fascism!'

I arrived in Gorna Dzhumaya in the afternoon on 9th September. We were welcomed with a ceremony at the station. There was a field, two kilometers and a half between the station and the center. Someone had told my mother that we were back and she met me in the middle of the field. It was such a meeting, such hugs... My mother was crying with happiness that I was alive, I was hugging her and telling her, 'Walk mother, now is not the time for sentimentality!'

After 10-15 days we returned to Sofia. Fortunately, our house was not destroyed by the bombings but had been completely emptied. My mother found some sacks, filled them with hay and we used them as beds. Months after that we received aid from the Joint Foundation 50.

The authorities from Gorna Dzhumaya gave me a document certifying that I had graduated high school there. 2nd Girls' High School also gave me such a document. I enrolled to study medicine because that was my dream. I also started work in the Commissariat on supplies. I issued ration books and clothes.

- After the war

In April 1945, just before the end of the war, together with a UYW group I traveled to the front to bring presents to our soldiers. I was in Hungary when Berlin fell. Let me tell you about the fate of the 'cock-a-doodle-doo', who became our friend in prison.

All criminal prisoners were also released with us, but she had already served her sentence. She decided to go to the front line as a volunteer – a medical orderly. In Pecs on my way to the front lines, I was hugged from behind and it turned out that she was there working in the hospital. We were very happy to see each other.

We had half an hour and then I had to leave with the group. I promised to see her again on my way back. I returned a couple of days after that. I did not find her there. The commander of the base told me that she had been sent to accompany a group of wounded soldiers.

On their way one of the wounded wanted water and they stopped in a forest near a stream. She went down to fetch some water but stepped on a mine and died instantly. When the commander heard that I was her friend, he gave me a packet of her belongings. Among them I found the poem by Vaptsarov which I had given her in the prison.

I stayed in Pecs to help in the hospital until the end of the war. I remember that I had very big braids then and one of the soldiers said to one of the Hungarian girls, 'See, what beautiful hair our Bulgarian girls have!'

After 9th September I worked and studied. It was possible the first two years because the teachers did not check if everyone was present at the lectures. We were 2 000 people, gathering in the Moderen Teatar [Modern Theater] 51 in the hall of the Student's Home – its stage. Then I started work in the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. I was head of the human resources department until 1951. When my studies at the university got harder, I had to stop working.

My father's shop had been confiscated. During the Law for Protection of the Nation we had to hand it to a Bulgarian. Some of the Bulgarians were very honest people and gave the shops back to their owners. But my father received nothing back and he continued to work as an electrical technician.

Our life was very hard. Our way of life during the internment was very miserable, but it did not get better after 9th September because the whole town was destroyed. The houses which survived the bombings were occupied by two or three families.

Our house was not big. One part was let out even before 9th September but there was no forced accommodation in it. All members of our family came back to Sofia. Everyone was alive. The house of my other grandmother was also preserved. It can be seen even nowadays.

The goldsmith, my uncle Zhak, started working again, but he had no gold, so he repaired jewelery. Soon after that the youngest brother of my mother left with his family for Israel. Meshulam and the two elder brothers remained here. Vizurka also left. So did my aunt. [Mass Aliyah] 52

I never considered leaving for Israel because I was convinced that now was the time to realize my ideals. My husband was even more convinced that we should remain here. He was against the aliyahs. He believed that Bulgaria was our home and we should stay here and realize our dreams and live freely. But a lot of the Jews, especially the richer ones and those, whose shops, factories and workshops were once again being nationalized in 1947, left for Israel. The others, their relatives and friends followed and it was like a chain reaction.

My husband Yosif Hananel Astrukov (1912 – 1996) and I were in the same prison – the Pleven one but we had not met there. He had spent two years underground. He had been district secretary of the UYW in Sofia. He had become a member of UYW in 1936 and he had been much higher in the organization hierarchy than me. His illegal name was Herz, made up by his friends. Herz means heart in German, because he was the soul of every company.

He was an orphan. His father had died when he was a child and he lived with his mother until he was 7 years old when she decided to marry a widower from Vidin and left him with her parents for a year until she got used to her new family and the two children of her new husband. She gave birth to one more child. (Later she left for Israel.)

But the parents and the sister of my father-in-law filed a lawsuit against the relatives of my mother-in-law in a Jewish court because they wanted their grandson back. According to a Jewish law they had to have their grandson. There was a Jewish court, which solved such problems in accordance with the Jewish laws, which were valid until the law. If the mother was to marry a second time, the child was given to the parents of the first husband.

So, my husband was raised by his father's family – three aunts and three uncles. [Probably this is the Spiritual Court at the Jewish municipality. Jewish marriages have to observe the Jewish marital law.

The books by Yosif Karo 'Shulhan Aruh' and 'Even Aezer' focus ont he following major moments – engagement, education, marriage, cancellation of the marriage, divorce, halitza (cancellation of the marriage due to lack of children). A woman's second marriage and its privileges are also subject to Jewish marital law. There was no civil marital institution in Bulgaria before WWII.].

They lived in a house on Strandzha Str. Now the National Statistical Institute is in its place. My husband finished high school, started studying law but he was expelled from the university for his participation in an attack against Tsankov. [Prof. Alexander Tsalov Tsankov, Prime Minister of Bulgaria from 1923 to 1925, terror activities were typical for his governance.]

His relatives collected money and sent him to study in Belgrade. When the Germans came there, he left for Prague. He finished his first and second year of studying there and when the Germans came, he went back to Belgrade. We stayed there five or six months but when the persecutions started again, he returned to Sofia.

He immediately joined the resistance, but in 1941 he went underground. He was underground from 22nd June until 26 November. In 1942 he was caught because he was betrayed. He was sentenced to death. But the jury was bribed – for 250 000 levs his sentence was changed to life imprisonment. In prison he shared a cell with Traicho Kostov 53, whom he much respected. Although Traicho Kostov fell into disgrace later on, he always spoke in his favor.

Until he was imprisoned, my husband had finished three years of medical studies. After 9th September when I started studying I had no textbooks and remembered him. I had seen him on UYW conferences. I remember that he was a delegate at one of them and I was not. In one of the breaks he saw me and told me, 'You see, we have badges and you don't.'

So, he took off his badge and gave it to me. I decided to visit him and ask him if he could help me find textbooks. It turned out that he had none, but he asked me out. So, we started going out, but we did not spend much time together because we were very busy. Those were tumultuous times. He was assistant commander of the armored brigade.

On 22-23rd September he took me to a formal meeting on the occasion of the September rebellion 54. He was suddenly called away because of a fire. It was impossible for me to go home – there was a curfew and he could go around the town because he was an officer. He left me at the place of a friend of his from prison.

They put out fires all the night and I fell asleep. In the morning he brought me back home. My mother was at the window, pale and very worried because the first days after 9th September were dangerous – a lot of fascist shot at us from hideouts.

They knew that only communist and partisans working for the Ministry of Interior could move around the town during the curfew. We did not see my mother and while we were saying goodbye and lifted my head and saw her. My parents did not know that I was in a relationship with him.

My husband came in and told my mother that his intentions towards me were serious and apologized for the late arrival. 'I have nothing against your relationship,' my mother said, 'but, please, don't do the same thing again, I was going mad from worry.'

So, that week he told me, 'We can't go on like this, let's get married!' He came to ask for my hand and next Saturday we got engaged. His relatives – uncles and aunts – came to meet my parents and we married on 13th October 1944. We were among the first in Bulgaria who married only before the registrar.

Before us there were only religious weddings. We did not have a ritual in the synagogue. We went to live with his family on Strandzha Str. As a bachelor he had lived in one of the rooms with one of his aunts.

Another aunt lived in the next room with her husband and the mother-in-law of the married aunt lived in the third room. When we got married, the aunt who slept in his room went to live with her sister and we occupied his little room with a balcony. We lived there for two years.

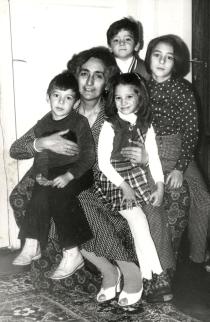

On 6th July 1946 I gave birth to the twins Evgeni and Emil.

In any case Evgeni and Emil learned some Ladino from the aunt who raised them. She knew Bulgarian but spoke mostly Ladino at home. My husband and I were very busy. We were both studying. His uncle and aunt opened a small shop on Dondukov Str. and started selling things they had collected even before 9th September.