Meyer Abramovich is an elderly person, an educated man of 85 years old. He smokes a lot

and is apparently agitated during our conversation.

He perfectly remembers many details of the life of his ancestors and is proud of his family history.

He lives in a small one-room flat.

Hesed volunteers regularly come and help him about the house.

Meyer Abramovich is very thankful to the workers of this charitable organization for their help.

In spite of the fact that his both legs failed him 10 years ago because of a serious disease,

he moves around in a wheelchair independently, without any assistance.

He lives very modestly.

His relatives do not abandon him in his solitude.

My family background

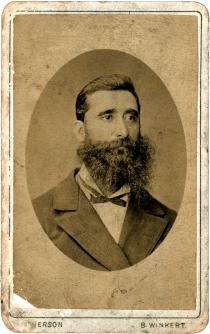

My grandfather Solomon Bentsman and grandmother from mother's side [name is unknown] come from Bryansk region. They lived in the district of Rechitsa.

They were born approximately in 1840. I know nothing about my grandmother, she died before I was born. My grandfather had a brother,

of whom I do not know anything either, except that he used to visit us when I was very small.

Grandfather worked in Kiev as an accountant for a well known Jewish businessman named Brodsky and kept all the books in Yiddish.

They always spoke in Yiddish in the family, therefore I know Yiddish well. He was a religious person and regularly went to synagogue.

All Jewish holidays were celebrated in our home and everything was done according to Jewish traditions.

I vaguely remember Sabbaths and other holidays. Grandfather wore a long beard.

I remember one episode: when I was 4-5 years old, mother once carried me past grandfather,

who was warming himself by the tiled stove wall, and I pulled grandfather at his beard.

Then mother chided me for my misbehavior.

My father Abram Markhasin was also born in the same Rechitsa region, but I can’t remember where exactly. Father had a Jewish education; he studied in a cheder, but, at the same time, he read and wrote Russian perfectly. He loved Russian classical literature and was a very clever and knowing person. Father also had two elder brothers Grisha and Gershim, but I do not know anything about their destinies.

Father got married for the first time in 1898, and they had four kids with his first wife. But she died of cancer. All through our lives we maintained relations with father’s children from his first marriage. As we got older we moved to different places. I only remember their names now: Efim, Tatiana, Rose and Blyuma. I don’t know of any details of father’s first marriage. He got married for the second time in 1911. His second wife was my mother. She gave birth to 5 children and I was the youngest: Perla [1912-1927], Mira [1914-1985], Tsilya [1916-1970] and Naum [1919-1927]. How my parents got acquainted and married, I do not know. Most likely, they had a Jewish wedding ceremony, since they both were from religious families and observed all traditions.

They named their two daughters in honor of mother’s living sisters, although it was not in the Jewish tradition: Tsilya and Perla. I do not know why it was so. Naum and Perla died in Novozybkov at a young age. Naum died at 8-years-old from meningitis, an illness of the brain, and Perla at 15, of pneumonia. They couldn’t treat children well enough then, penicillin and other antibiotics were invented only later. And of course, the children suffered a lot. After that I was left with two sisters - Mira and Tsilya, who I loved very much, and who treated me very well. We lived very amicably, loved and cared for each other, especially they for me, as I was the youngest. Even after the war my sisters still took care about me, their younger brother. We adored each other, we had a very good family. The native language of all my sisters and brothers was Russian, but with parents we talked basically in Yiddish. At the age of six I fell in love with one girl and often insisted that my sisters took me to her place. Sometimes they refused and I misbehaved.

My sister Mira lived in Pushkin and Leningrad. She completed a course of accounting after a ten-year secondary school and all her life worked in Leningrad as an accountant in trade. During the war she was in evacuation in the Kirov region together with her husband and children. Mira had two daughters: Eleonora and Tatiana. Eleonora was born in 1943, worked as an engineer at the factory named after Kulakov in Leningrad. In 1993 she emigrated to Israel. Tatiana was born in 1945 in Leningrad, completed a technical school and worked at the Kirov factory as a designer. Mira died in 1985 in Leningrad. Their family was not religious, led a secular life. They did not adhere to Jewish traditions.

My sister Tsilya completed the Pedagogical Institute in Leningrad and all her life taught Russian language and literature at school. She lived in Pushkin, then in Leningrad. Tsilya was in evacuation during the war in the town of Slobodskoye in the Kirov region. Her husband and his three brothers fought in the war and all perished, except Tsilya’s husband. He was wounded, and after treatment in hospital arrived in Slobodskoye. They had no children and she adopted a girl named Svetlana from a children's home, and this adopted daughter of hers now lives in Israel. Tsilya died in 1970 in Leningrad. The family members of my sister Tsilya were atheists any did not maintain any Jewish traditions.

Growing up

I was born in Gomel in 1917. When I was a baby, my family moved to the town of Novozybkov in Bryansk region. There I lived until 8 years of age. Novozybkov was a small but a very cozy town. Father purchased a beautiful two-storied house where we lived, and two small wooden houses near the big one: one in its courtyard and the other just beside, with windows overlooking the street. We leased wooden houses to other families. There was a veranda with colored glass windows. We had a huge fruit garden. The houses were heated by ovens. We prepared firewood for the winter. We had no helpers about the house. Everything was done by mother alone. She could handle the household and her four small children; she was a really hard-working woman. She was a very kind and caring mother. We had some books at home: classical Russian literature and Jewish books - Torah, religious books. My parents read newspapers.

Father knew all prayers by heart, he prayed at home. Father and mother were very religious, father went to the synagogue on Saturdays and holidays. At home we celebrated Jewish holidays and everything was done per Jewish customs. When I was small, in pre-school age, father hired a rebbe, a teacher, for me. Rebbe used to come to our place and teach me Hebrew, Yiddish, how to read, write and so on. This continued for one year.

I do not know whether my father had done his military service, but in my opinion he did not serve. Neighbors liked to be friends with my father and mother - they were very good and hospitable people.

My parents hardly ever left town. Father started a business in Novozybkov. What else could you expect of a Jew at that time? He manufactured hempseed oil, installed the corresponding equipment for that purpose, and sold the oil. Then in 1925 there was a fire, I do not know how it happened or why. The business burned down and we lost much of our fruit garden too. Someone had set fire, I think, out of envy. Before the fire the family had enough money, everything was good. And now we had to survive somehow. Father made a decision to go to Leningrad, since his elder daughter Tatiana (from the first marriage) lived there. Before departing to Leningrad, father made everything that was necessary for our family to live temporarily in the settlement of Kholmich, where the three aunts, mother’s sisters, lived. Then our family moved to Leningrad in 1925. It was the times of NEP [new economic policy]. We went by train and there were so many people, I can’t remember the details. Father rented an apartment in Pushkin, in the suburbs of Leningrad.

It was in Pushkin that my childhood and youth passed. I have photographs from Pushkin. I did not attend kindergarten. In Pushkin I was already of school age and entered the third grade. I had very interesting friends at school. I can remember my friends now. One of my pals was Edgar Lvovich Nittoburg, he is now a doctor of historical sciences, engaged in the studies of origin of nations and ethnography. Nittoburg lived in the Lyceum and his father was a writer. My other friend was the half-Jewish Varshavsky, who died a long time ago, and the third friend of mine was a Jewish kid, Kukhlinsky. All of us were friends. We walked near our houses and played together. My favorite subjects at school were literature, history, physics and mathematics. Apart of school we were interested in philosophy, the works by Hegel and Feyerbach. We got these books from our school library. I did not like my German teacher, because I felt something unpleasant about her. We composed a poem about her: "Ich bine dubine-poleno-brevno, everyone knows, the German is a swine for a long time! " Later, when Germans came to Pushkin, she worked for them and left with them, because in her soul, she must have been a fascist. Others were good teachers. I did not feel any anti-Semitism then. I had a duel in the eighth grade because of a girl, with whom me and my friend were both in love. Her name was Yana Bokanovich, a Pole, very beautiful. We had such a tradition, if there was a dispute, we organized a "duel", until the first blood. We went outside, behind such a big lavatory, my supporters at my side, his close to him, and the scuffle began. In that particular fight he immediately smashed my nose, I started bleeding, and when I hit his chin, he, too, had blood, and the duel was over.

The most interesting thing in my school history happened in 1936 when Stalin declared the former “nepmen” [businessmen in the time of NEP] deprived of electoral rights. These people – “lishentsy” - were ordered to leave Leningrad under the decree of the Central Committee of the Communist party. [People undesirable for authorities were not allowed to live closer than 100 kilometers to large cities, that’s how the well-known expression “101st kilometer appeared”]. When I was in the 9th form, I had to pass examinations. It was the final class, it was a 9-year education then. And my parents were forced to leave Pushkin for "the 101st kilometer". I didn’t go with them, I stayed to prepare for examinations, and when I came in the morning, my parents had already left. That same morning I went to see my sister, and she said that a little earlier the militia came to arrest me for not leaving with my parents. I was not even allowed to finish school, I had not passed examinations for the 9th grade and was compelled to join my parents at "the 101st kilometer".

First we lived in Malaya Vishera in the Leningrad region. Then I began to file in petitions to allow me to study. For that purpose I went to Moscow and took a letter to Kalinin [state and political figure, nearest coworker of Stalin], to the public prosecutor, but nothing helped. Everyone threatened to arrest me if I continued to pester them with such requests. At the same time father went to Borovichi- it used to be in the Leningrad region, now it was in the Novgorod region. There he agreed with one family and rented a room for me and arranged for me to work at the factory "The Red Ceramics" as a simple worker. I worked there as a stamp operator. Not long afterwards Stalin mentioned somewhere in a congress or a party conference that "the son is not responsible for the father." In 1937 I entered the 4th year of a rabfak [a special educational institution for workers], finished it and returned to Leningrad. Once there, I passed an examination and in 1937 entered the Institute of Technology named after Molotov. I studied for 4 years there.

I entered the 1styear of the institute, and on vacations visited my parents in Borovichi, where I got acquainted with a Russian girl Zoya Solomonova. It turned out that this girl had just finished the tenth form and tried to enter a medical institute, but failed to pass her tests. So she entered our institute, the faculty of building materials, and she appeared to be my fellow student. When my sisters disclosed to my parents that I was courting her, and I was on a vacation to Borovichi, father told me that I should tear off any relations with her, because I was a Jew, and she – a Russian, and it was against our national tradition. He even fell down on his knees before me, begging me almost with tears in his eyes. That scene touched me so much that I broke off with her. In summer in Borovichi I didn’t communicate with her. In this time my parents became soviet people and stopped keeping Jewish traditions.

Then I came to Leningrad to proceed in my second year in the institute, and Zoya was in her first. Once I was walking along Nevsky Avenue. And she had a friend, Gurevich Masha, so I came across the two of them. It was in late autumn. They came up to me; involuntarily we started talking again, and as a result my infatuation for her continued. It was already in 1938. We were friends. My parents certainly did not know it. In 1940 it passed on to closer relations. We lived in a student's hostel.

During the war

On June 22, 1941, in the morning, we learnt that the war began. I had passed to the 5th year in the institute by then. We stayed in Leningrad during the siege for half a year [from September 8, 1941 to February 1942]. Girls who lived close in the Leningrad region went to their parents at once, and we men were sent to the Karelian Isthmus [territory in the north of Leningrad region won by the Soviet Union from Finland in 1939-1940] to dig anti-tank ditches. I can’t remember exact dates, but in the end of July there came a new decree by Stalin that students of the fifth year shouldn’t be taken in the army, and those who had enlisted had to be released and finish their institutes as soon as possible. they would be assigned jobs later because staffs were greatly reduced, - in the first months of the war many people were "ground up" [in the first days of war more than 2 million. Soviet soldiers were lost].

Zoya was at that time in Borovichi. When we were called back to the institute, we returned to Leningrad. Literally the next day, when I was about to go to sleep, I heard a sudden knock on the door of my room: Zoya came back from Borovichi. I said: "What, are you nuts, there’s a war going on, and you came back to Leningrad!". She said: "We heard that you returned to the institute, so I came back to be with you". At that time she was already pregnant. Seeing such a situation, when I was not sure what was going to happen to me, the first thing I told her was: "We shall go to the registry office tomorrow, I do not want my child to be fatherless. We are going to get officially married".

My parents did not know anything as they were in evacuation far to the east. So we went to the registry office and got officially registered. There was no wedding. I told her: "Now go and pick up your things." I was released from army service. I was given 10 days to take her back to her mother in Borovichi. At last she had collected her things – she had a lot of them. On August 1 or 2 we left the city with Germans already on the outskirts of the city. When we were approaching the station of Chudovo, our train was suddenly attacked by German planes shelling us hard from machine guns. People fell on the floor, I, too, made Zoya lie down and covered her with my body, so that if we caught a bullet it wouldn’t reach Zoya. We stayed alive. We were lucky that those "Messerschmitts" were chased by our planes. Those fascist aircraft fired at the train once and flew away, unable to shoot any longer. The train stopped, we jumped out and ran into the woods.

When we recovered from the stress, we started thinking what to do next. I told Zoya: "Let’s go back, the train will probably go ahead." She said: "No way, I am not getting on that train never again!" OK, you don’t want to get on the train, let’s travel on foot. I went back to fetch our things. We kept fussing between ourselves all the time – I wouldn’t let her carry anything heavy, and we had three bags. We were arguing on who should carry which bag. There was a railway station Gryady nearby and the headquarters of the Soviet marshal Clement Voroshilov was located there.

Why were we shelled by the planes just then? There were many betrayers and spies sent by the Germans then. Chudovo was a big railway station with lots of trains with military equipment and arms. The German planes started to bomb those trains. A hard bombing took pace on the eve of our arrival. When we were passing Chudovo, in the radius of 2 kilometers everything was destroyed: trains, railway cars, weapons were scattered all around. A huge area had been bombed. Voroshilov learned what happened and went to inspect it all with his retinue, and the Germans found out that Voroshilov was there, and didn’t let any passenger train pass without bombing it, and we got under that firing.

We reached Bolshaya Vishera, then Malaya Vishera got very tired, and one lady let us in her yard to spend the night in the hayloft. Then I went to the market place to ask for the way to Borovichi, and they told me that there was a highway Leningrad - Borovichi. I asked how many kilometers away it was. Some said 20, others 40, nothing was clear. Someone gave us a lift to that highway. And in reality that road was full of holes, pits and bumps everywhere, it was hard to walk, to say nothing of riding. It was horrible. We walked along. Then we got another lift. There was one military aircraft unit nearby. I addressed the headquarters and the next day they let us ride in a truck heading Borovichi. The trip took us a lot of time, and I had been given only 10 days for my leave, so I had to leave Borovichi in a couple of days and set off back to Leningrad. It was already the end of August. And on September 8 Leningrad was completely surrounded by fascist troops. We, men lived in a hostel. There was no public transport and it was a very long way to walk to the institute. That’s why we moved to the institute premises and lived in a lecture-room. We installed a small stove there. We received only 125 grams of bread each for food cards and worked as cleaners in the institute courtyard, and then began to receive 250 grams of bread each as workers. Germans had bombed and destroyed the Badaev warehouses [one of the main stocks of foodstuffs in Leningrad], and the city was left without food.

Famine began, people were dying of starvation and cold. We were given a plate of soup in the institute canteen, consisting of water and 10-20 grains. For the main course they served cutlets of fish bowels, but I didn’t eat that. I had an acquaintance at a furniture factory, and I got hold of a few bars of joiner's glue there. One of my Russian friends used to bring wooden sawdust from his factory and cook porridge out of it. Any humane qualities that a person had at that time vanished and what was left inside was a beast. A very small percentage of people remained normal. There were so many examples of that: for example, a husband beat his wife because she forgot to bring a small slice of bread. Or another example: one of our fellow-students found that his bread card was missing and began to search everybody. The card was found in a sock of another student. And in those times there was an order by Stalin: the death penalty for the theft of bread cards. What followed was that each of the students hit him in turn and we took him to the militia. We never heard about him after that. When I was leaving the besieged city of Leningrad, I saw how a mother was handing over her deceased child-- without tears and without emotions-- to somebody else to bury. Coffins were dragged on sleds to the cemetery all along Leningrad streets. In the institute, where we lived, there were corpses too. We wrapped them in blankets and carried to the foundry laboratory of the institute, because no one felt like taking the dead to the cemetery.

During the first months of the blockade I had connection with Zoya, and in November 1941 I received the news that my first daughter Alenka was born. It was on November 7. I had an excellent English suit because I was father’s best helper and he didn’t begrudge me money. The fabric was called "the English mat." I haven’t seen such costumes since. I remember bragging about it in front of the other students. You could easily rumple the trousers in the evening and throw them under the bed, and in the morning they would look as though freshly ironed. I went to the commission shop, sold that suit and sent the money as a gift for the birth of my daughter. It was the last time I communicated with Zoya.

I was lucky to get evacuated in February 1942 via the frozen Ladozhskoye Lake. At first I went to see my wife in Borovichi. On the way I ate something wrong and felt really unwell. I was sitting in the station buffet with other evacuated students when an officer approached, asking: "What’s the matter with him?" They said: "Something wrong with his stomach, he’s dying." The officer quickly reached into his field bag, took out some powder and asked the bartender to get some water. Then he put the powder in the water and the guys opened my mouth and poured half a glass of water in. A bit later my stomach got better and I more or less revived. In this condition I arrived to my first wife in Borovichi. I was suffering from dysentery and could hardly stand on my legs. We were allowed free food in a canteen for the blockade survivors and were fed five times a day. But most interesting: when I approached the house of my wife and knocked on the door, she asked: "Who is it?» and I said: "Mark". It was for a long time known that people were dying in Leningrad, and she considered me dead. She opened the door pale asceiling plaster wondering how I managed to get out of that hell. For some time I lived in Borovichi with her, our four-month daughter Alenka and Zoya’s mother.

All my relatives and parents were evacuated to Slobodskoye, which is in the Kirov region. After the war they returned to Leningrad. There was a fur factory where my brother-in-law worked, and my father, mother and sister lived there too. I went there and read an announcement, that in Urzhum, the evacuated Moscow Institute of Light Industry was now located and that it admitted students.

I wrote a post card to Urzhum asking if they had a mechanical faculty. They answered positively. I wrote that I completed 4 years in Leningrad. They invited me to come and to continue my studies. And I became a student of the fifth year there. I got acquainted with my second wife Ekaterina in Urzhum. My institute was located there. I named her tenderly Katyusha. We loved each other very much. As I already said, I had not any connections with my first wife since November, 1941.

My wife was born in Ryazan, she was Russian. When she finished institute in 1943, it was Moscow Institute of Technology of Light Industry named after Koganovich [the leader of Communist Party]. She arrived in Leningrad, where I already worked. When we started to live together we had no flat of our own, so we lived with my parents for some time. Ekaterina became my wife from the very beginning of 1943, and our son Boris was born on December 1, 1943. I was summoned to Moscow from Urzhum to write the diploma, and I left. A bit later my wife joined me there. In 1-2 months I saw that she was going to give birth to a baby soon and I sent her to Ryazan, where all her relatives lived, because we lived in a student's hostel, in a separate room. The labors began in the railway car, so she was at once sent to a hospital after arrival, and she gave birth to our son Boris.

After the war

In 1944 in Moscow I defended my diploma and was assigned a job in the city of Kalinin, now renamed Tver. I worked there until 1946 at the factory "Kreps" which produced rubber for shoe soles. When they asked me where I was from, I said I was from Leningrad, so in the protocol it was written: "With subsequent transfer as a young specialist to Leningrad." In Kalinin I also worked at an enterprise of light industry called "The Russian Diesel" factory. I was transferred there from "Kreps" as a chief mechanical engineer. I moved there in the times of the notorious "doctors’ plot" in 1952. It is interesting, that the acting chief mechanics, a Russian and a Party member, was dismissed from his position, and a non-party Jew was hired instead. I arrived there at such a time, when Jews were simply thrown out of buses and trams. I was met extremely coldly in the factory! The director began to follow me everywhere and kept an eye on me to see where I would fail. My every wrong step was reported to the Ministry and there were innumerable complains. But it was very interesting, and now I laugh when I remember it, but then I suffered a lot. The situation was like this: I often visited the Head Office where I had a lot of friends, with whom I was in the institute, and they would tell me everything, so I was always informed of all those intrigues. Before I occupied my position, there was an engineer working there from the factory "The Red Triangle," who had designed some kind of semi-automatic machine. They produced paints and round shoe polish tins with a label. With the help of his fingers and gesticulation and without any design documentation or drawings he commenced to show how exactly he was going to build his apparatus. And by the time I appeared there they had already spent an enormous sum of money on that machine. When I arrived and saw the kinematics, I understood that the device wouldn’t ever work. I came to the director, not knowing who hired the guy, and said: "What kind of fool was this who could employ the guy who has neither drawings nor any documentation and who shows everything using only his fingers? Heaps of money have been already spent, and nothing is going to come out of this automatic device!" And it turned out that the director himself appeared to be that fool. It was horrible! Finally, I quarreled with him and filed an application on dismissal. I worked in Kalinin for some time, from 1944 to 1946, and in 1946 quit my job and went back to Leningrad. After the war was over we returned to Leningrad and I worked at the factory "Russian Diesel" from 1946 to 1947 in the department of chief mechanic as an engineer.

She was a very capable person. She heard that I spoke Yiddish with parents and wanted to master this language. Literally in 2-3 months of our joint life she learned the colloquial Yiddish. Much later, already after the war, there was one interesting episode. We came to the synagogue to meet father from some prayer or fast and take him home, and in the side wing there was a crowd of women and men who had not found seats. And my wife is a typical beautiful Russian woman. Two Jewish ladies began talking in Yiddish that there was this Russian woman standing there for some reason and my wife overheard it, turned to them and said in Yiddish: "My husband is Jewish, here he is, standing beside me". Certainly, my parents grew fond of her at once and she mastered Yiddish fast, being very talented. We loved each other all our lives, in spite of me being very jealous. Men admired her, and we had short quarrels for this reason.

Family life in that period was hard. Not only ours, certainly, but of every family around. I lived in Kalinin in the house belonging to the factory "Kreps". All products were distributed for cards. We had a small child, Boris went to the kindergarten. My wife also worked as an engineer at the factory "Kreps." From 1948 to 1951 I lived in Kalinin again, where I was assigned to work as the deputy head of the mechanical factory. My wife and two children lived with me. I had been humiliated many times in my life, as I already said. My second child, daughter Tanya, was born in Kalinin in 1950. Because I was not divorced with my first wife-- we had been separated by the war-- I could officially marry my second wife only in 1956. Two children had already been born to us before that.

There was this "doctors’ plot" in 1952, but I still managed to be on good terms with people somehow. The death of Stalin in 1953 was a good news to me, though many people cried. Though we had always been duped, I knew for sure what kind of man he was and how much trouble he had brought to the Jewish people. And had he lived another year, the Jewish people would have suffered from him even in a greater degree than from Hitler. I returned to Leningrad in 1952 and worked as the chief mechanical engineer of the Leningrad Chemical Plant of Light Industry until 1958. From 1958 to 1974 I worked as the chief mechanical engineer at the Leningrad Fur Factory. From 1974 to 1977 I was the chief mechanical engineer of the four joint fur factories of Leningrad and Leningrad region. I have been retired since 1977. After retirement I began thoroughly to study the Bible and read all of it on Russian. I began to adhere to faith in the last 10-15 years.

My father and mother lived separately from their children in a room in a communal flat. All the children helped mother financially, since the parents did not work, were already retired. Mother died in Leningrad in 1955. Father pronounced the Jewish requiem "kadish" at mother’s funeral. Before his death father left me a copy of the prayer in Russian, and I read it in Preobrazhensky Jewish cemetery. Father died in Leningrad in 1963. My sister Mira is buried there too.

Recent years

My wife and me celebrated only the Jewish New Year and Pesach. I believed these two holidays were the most important, as well as Purim, which we also celebrated, but not as solemnly. We knew that on Purim it was necessary to bake poppyseed pies, on Passover we always purchased and ate matzot, cooked gefillte fish. I tried not to eat bread and matzot at one time. Thus, my family knows about the most important Jewish holidays. My friends were mostly Jews. But I also had many good Russian acquaintances. Now I call them over the telephone from time to time, but I haven’t been out of my apartment for more than 10 years: I suffer from atherosclerosis of lower extremities, my legs do not obey me.

My son Boris finished the medical institute in 1969, and became a dentist. My first daughter Alevtina graduated from the Institute of Technology named after Lensovet in 1965 and worked as an engineer in microelectronics. My second daughter Tatiana completed the economic faculty of the Institute of Technology of Paper Industry in 1972 and worked as an economist. Boris has his own family: a Russian wife Tamara, and a son Anton. Tatiana has a Russian husband Vitaly and two sons: Alexander and Edward, my favorite grandson. My children did not have any troubles because of their Jewishness, because they were not considered pure Jews. I didn’t worry about them too much. I personally had felt a lot of anti-Semitism in Stalin times, especially in the period of struggle with cosmopolitanism and "the doctors’ affair." I remember there was an issue of "Ogonyok" magazine, where on the cover there was a portrait of a man with a long nose and the inscription said: "Cosmopolitan."

When in 1948 the state of Israel was formed, the Jews were not allowed to leave this country, and there was no question of moving there. Now my niece, the daughter of my sister Mira, lives in Israel. I painfully reacted to wars in Israel in 1967 and 1973, and now I feel upset about everything that is going on there now. I consider Palestine the native land of my people, and I consider Russia my motherland, since I was born in Russia, and all of my ancestors lived and were buried here. I have not been to Israel, but my two cousins and a niece with her family live there. Israel is our state. It should always stay Jewish.

In their souls both my daughter and son are Jews, they are proud to be Jews, all the more so that I tell them a lot about the Bible, about our Jewish prophets, about Moses, who released Jews from Egyptian slavery, and received 10 Commandments written on tables on Mount Sinai, from which the Torah and the Jewish religion began. They know all of it. And even my grandsons know. I also told them what happened to our family during the war. So they have learnt a lot from me. This knowledge has passed to them from me, and to me from my father. Already living in Leningrad, father was a member of “the twenty” in the synagogue, in the Jewish community. He told me many stories from the Bible. I later passed it all on to my kids. This is reason why my two kids have a Jewish soul although they have Russian mother. We keep our heritage.

There was never any democracy in this country, although we are now allowed to chatter about everything. We have to wait at least another one hundred years for a real democracy in Russia. I would not explain that is clear without explanations.