Matilda Levi

Sofia

Bulgaria

Interview: Violeta Kyurdyan

Date of interview: March 2002

When I entered her home for the very first time, I found myself in a wаrm and cozy apartment in the most beautiful part of the center of Sofia. Matilda gave me a friendly smile as she invited me to take a seat. I didn’t see any pictures on the wall, nor did I notice any precious objects around. No bright colors, nothing to grip the attention. Everything in the room was clean, modest, and simple. Matilda was sharing that apartment with one of her sons at that time. Presently, after having badly broken her leg, she lives in the so-called Parents’ Home for elderly Jews. When I went to visit her there, I had the same impression of coziness that I had had at her home, as if she had brought the sprit of her home with her. She was joking and smiling again, but she couldn’t walk well enough yet and she was suffering of not being able to go down to the garden, but had to walk around with her support along the corridor instead. Though, she’s still the same charming and shining person I had met, despite the pain and the inconvenience, which the accident has brought to her life.

My maiden name is Behar. When I was small, we spoke Ladino 1 at home. I used to speak that language but now I’ve forgotten it a little, of course. My grandchildren don’t speak [Ladino]. Bulgarian culture surrounds us.

I come from Karnobat. My [paternal] grandfather Moisei Behar ran his own business. He had a little shop down at the square. He used to sell textile, haberdashery, fancy goods, etc. A lot of people used to come from the villages. There was a connection with the villages. Women weren’t allowed to go there; it was regarded indecent in those times. Sometimes I went there. When I was a child my grandfather wasn’t interested in the children at all and he even mixed up their names. My grandfather could read in Bulgarian. He read newspapers, but he couldn’t write. My paternal grandmother, Vida Hason, came from Bourgas; my grandfather brought her from there. She came from a notable family. My grandmother was a real housewife though she could write. I wondered why, when she started writing something, she wrote from right to left. She didn’t explain. I suppose it must have been a text in [old] Turkish; I don’t know even now what it was. She spoke fluent Turkish.

My grandmother had seven children and they all went to different places. All of my aunts and uncles received their education in Bourgas, and one of my aunts in a French boarding school in Rousse. Later, all of them except my father went to Israel. He remained here because his ideology didn’t allow him to leave. I don’t know what was better: to depart or not.

My other grandmother, my mother’s mother, Bohora Behar, came from Yambol and her father was a rabbi there. They called my other grandfather, Mordehai Behar, Bukorachi-the-drummer. He was bald headed and had a little beard. We had a big portrait of him and he looked just like Lenin, at least that’s what Lenin looked like in the photos I’ve seen of him. We hung this portrait [on the wall]. Later we had to hide it because he looked so much like Lenin. When he was going to work in the mornings, he passed by our house. He had a big cane with which he could reach the first floor window and he knocked to tell me good morning and then he went on to work.

My father, Yosif Behar, was born in Karnobat in 1888. He studied in Karnobat till the third grade [the seventh grade of elementary school at present]. Everything was just fine but where could he continue studying? In Plovdiv, of course. So, he was taken to Plovdiv. There’s a big and very famous secondary school there. Samodumov and Barutchiyski [eminent Bulgarian intellectuals] taught my father there: these are men who later became professors. He received a very solid education. He studied math really fundamentally, descriptive geometry, rhetoric and Old Bulgarian. He could recite Chernorizetz Hrabar and Cicero’s speeches by heart. [Hrabar was a Bulgarian writer from the end of the 9th century, the so-called Golden Age of the Bulgarian culture.] He was very keen on math but he could also draw very well and could write in calligraphy: they studied calligraphy at school. When we had to make chemistry tables in secondary school, he made them for me and they were always hung on the classroom wall. He sang lots of [Bulgarian] folk songs. He didn’t study Hebrew at all. But he knew some prayers by heart and also their translations.

After he graduated, he did some accounting courses. When he first went to Plovdiv he was 13. He wanted to go back home. He left school and walked from Plovdiv to Karnobat on foot, because he didn’t have any money. But after that he returned to Plovdiv and continued studying. My father often said, ‘We, our family, eat boza 2 and halva in Plovdiv.’ That was the cheapest food and the rest was expensive. He said, ‘We didn’t know what toothpaste was then. We baked bread until it became black, then we pounded it and brushed our teeth with this paste.’ And he died without a tooth pulled out.

After he finished his accounting courses, he came back to Karnobat. He was accepted as an erudite man. My father had been in a non-commissioned officers’ school. He didn’t take part in the war [WWI] although he was some sort of a commander. After he graduated from school, he was told that he had a valvular disease and wasn’t fit for active service. So, he was never sent to the front. He spent all his life with this disease. He had a wonderful handwriting, like a calligrapher. He became a clerk at the Dimitrov brothers’. They were businessmen. He had to go around the villages and market their goods. Then he bought a horse and rode around the villages; I don’t know if he had a cart. He was really in the circle of the Karnobat intellectuals because he had graduated from secondary school.

Life in Karnobat was rather patriarchal. We Jews were around 100 families or maybe fewer. All of us had to be religious. There was no way out, because your neighbor would immediately say, ‘Look, he isn’t religious!’ and so on. Even on Friday evenings my grandmother wasn’t supposed to switch the electricity on, or even touch the switches. Some Turkish woman used to come to turn the lights on. I remember that we used gas lamps. I was ten when electrification finished. I was living with my father, mother and my uncle, my father’s brother, in a one-storey house. Both my grandmothers lived in their old-Bulgarian houses, with a front square bay, just like the Koprivshtitza houses. [This is a small and picturesque Bulgarian town, famous for its houses built in the Bulgarian national revival tradition.]

We didn’t live in luxury. We had a hall and two or three rooms. When all of us, the grandchildren, gathered we used to all sleep downstairs. There were cupboards where, according to the Bulgarian tradition, we used to put the mattresses. And when it was time to go to bed we climbed up, it was a little bit high, and we rocked on the mattresses, which were really soft. It was very funny. Then we put the mattresses on the ground and slept there.

There was great poverty in Karnobat. We lived in the Jewish quarter. When holidays were close my mother used to prepare something that I carried to the poor: roasted chicken or something like that. Money was collected, too. It was something like a synagogue fee. Poor people were always given something. They were given some work. Sometimes Turks came to broom the yard or they went to the school fountain to bring some water. Otherwise, I used to bring the drinking water. Sometimes my father got up at 4am to go for water because there was no running water. The tap was leaking and there were great queues. My paternal grandmother had a well and a pump but the water wasn’t good for drinking. The pump was for irrigating. There were flowers in the front yard and in the back yard; there were tomatoes, peppers and parsley. They were irrigated because there was a lot of dry heat in the summer. I helped in irrigating and cleaning the garden.

Karnobat had its madmen. But the madmen were really harmless and there was Mad Sarah; she was a Gypsy. She wandered down the quarter, spreading gossip, but she was not ill tempered. Everybody loved her and she gave instructions everywhere. For example, I had a cousin whose mother had died during her birth. I don’t know how Mad Sarah had learned that Iveta would soon come but she pulled me aside and said, ‘Now listen, Mati, Iveta will soon come to your house. Tell Grandmother Vida to look after her carefully because it’s a sin; she’s an orphan. Look after her very carefully, right?’ Well, that was it – she was mad in a very special way. There was another madwoman but she was kind of grim. Sometimes she came to work in the yard and we had to give her food. But she was always grim.

After my father got married he moved to work with his father-in-law who traded with different foods. Many people came from the villages and bought goods: groceries, victuals. It was a small shop, not very beautiful, with a little office next to it. When my aunt graduated from the school in Bourgas, she became a clerk in this shop. My father worked there as a clerk, too. There was a store full of different packages and there was high grass in the yard; it was very pleasant to walk on. A big turtle used to live in it and my father told me that the turtle would live 300 years. I liked sitting on it very much and from time to time it showed its head off the carapace.

My father worked there; it seems he was doing well in business. He went to the villages; he had much communication with the villages. He had friends there, they used to come and visit us. Karnobat is situated in a wine-producing area. They used to bring him wine and grapes; they came with baskets from the villages. Sometimes he took me along. There were some rich villages: Sungurlare for example, which is a town nowadays. There were lovely houses there. People were living well. However, once he took me to the village of Seymen and I was shocked by the little huts there. They were made just of clay and the roofs of thatch. I was shocked by the poverty there.

My mother, Rashel Behar, was my father’s first cousin. She graduated from a French boarding school in Yambol. She has shown me what they had embroidered at school and it was incredible. It looked as if it wasn’t made by a human hand. She embroidered magnificently. She spoke French. She was a housewife.

I was born in 1919. When I was a baby she didn’t have any milk after some time, so the priest’s wife suckled me. I had a brother, Mois Behar, born in 1921, who died of dysentery when he was two. These were times when dysentery couldn’t be cured. So I grew up alone and the eggs and milk were all around me. We had milk for breakfast and my father, since there were hens in our yard, would come and say, ‘I’ve got it from the hen’s butt, eat your egg.’ But I began drinking milk only when I got pregnant because I had to. Otherwise I didn’t even taste milk. My father ran after me in the yard, but I didn’t want to drink. However, I ate yogurt. If it wasn’t ready or it hadn’t ripened in the evening, and it was sheep’s milk, it ripened perfectly, if it wasn’t ready, I was sent to buy some. And they cut some for me; it could be cut with a knife, in a large baking dish. The dairyman cut some and the milk was so thick that it didn’t seep water. So I brought home some milk from the main square and it was our dinner. Butter was harder to find. We had salami [sausages] when we made some for ourselves but it was hard work. We used to make different kinds of jam: we did that in the yard, in a large copper baking dish slaking the mixture with a big stick. I helped a little: cleaning the plums, looking after the hens in the yard and so on.

[In the morning] the greengrocers and the cheese-sellers passed by. They were Albanian; we used to call them arnauts [inhabitants of Albania and neighboring mountainous regions]. So, my mother would take something like a plank, or a stick, long and flat, on which you sign what you have taken, we called it a ‘rabosh’. It was like a credit card. We signed a notch on the ‘rabosh’ and we were able to take cheese. Neither the man nor we would ever lie to each other. One couldn’t lie just like that. It would have been so absurd.

My mother had a housemaid, a Turkish girl, from time to time. Our house wasn’t large so the housemaid came and went. We spent most of the time in the yard. It was really nice there; I played with the hens. It was interesting: there was a big plum tree. We put swings on it and so my cousins and Jewish friends and I rocked on it. In fact, it was a really close community. When it was winter and the snow was thick my father made a little path. Sometimes, probably because we were so poor and we were always in the yard, our legs suffered, they just froze, and became red. Then my grandmother said, ‘Now I’m going to heal you.’ And she let us go barefoot in the snow. We walked barefoot in the snow, our legs reddened and then we sat right next to the stove. That’s how our feet were healed.

There was a Turkish girl at my grandmother’s who spoke Hebrew, Bulgarian, and Turkish. All she had to do was to play with us; we were three or four cousins and she was a little older and we respected her. This girl, Hayriye, was a very alert Turkish girl, an orphan. Her grandmother was a friend of my grandmother’s. When she [the girl’s grandmother] came, we all stood up. That’s because she had authority. She predicted my fortune by throwing hot lead. When she came, my grandmother said, ‘Be quiet, don’t move and don’t shout.’ So she came, she sat on the couch and she was given some coffee. She said, ‘Come here so that I tell your fortune by lead.’ She had a veil that she put on my head and started mumbling something and I got very scared. At some point I heard something hissing. The lead was put in boiling water and started sputtering. Then she took the veil off my head, she took the lead out of the water and began telling my fortune. She gave instructions to my grandmother who answered her in Turkish, so I didn’t understand. At some point she said, ‘Don’t be afraid’ and I understood she was curing me of fear. Then she left and we started playing our games with relief. Her granddaughter, Hayriye, was the leader.

Then Hayriye grew up. When she became 16, my grandmother Vida sewed a veil for her. Although I already understood that Ataturk 3 had come to power and veils could be taken off, no Turkish woman from our town took her veil off and Hayriye had to be given a veil. She was opposed to that, ‘I don’t want a veil, I want to be like Mati [short for Matilda], like the other children…’ ‘You can’t’, my grandmother said, ‘put it on, when you’re going to the fountain, and after that take it off.’ So, she went to the fountain with a veil on and when she returned she removed it and stayed without it at home. But it was a great burden for her. Then she liked going to the fountain and flirting. I sometimes noticed her flirting with some Turks.

I spent all of my childhood at my father’s mother’s. She took care of me all day long and combed my hair. When I woke up my hair was always messy, curly somewhat. My mother didn’t have enough patience to comb my hair. She used to start combing me but it hurt me a lot. I sometimes even ran in my nightgown to my grandmother’s who lived on the same street. And my grandmother asked me, ‘Your mother pulled your hair again, didn’t she? Come here.’ And she put me on a little chair with a mirror and said, ‘Take a look at yourself and tell me how you want me to style your hair.’ She started to form a curl here, a circle there, I was really glad because she didn’t pull my hair.

I wasn’t sociable as a child. I was a child with my own concepts and didn’t like others imposing their will on me. I always ran to my grandmothers. My grandmothers’ houses and our house were very close but I didn’t communicate a lot with my mother’s parents; they were much more reticent people. My [maternal] grandmother was a fantastic cook. She made really tasty dishes: the meat-and-vegetable hash and the sweets she made were fantastic. For example, she took almonds, pounded them, mixed them with eggs and other things and the result was great almond cakes. She had a room where she stored lots of nuts and almonds and sacks of apples for the whole winter. She was a good woman and had a very white face. She was rather bumptious with her complicated meals. Despite that I went to Grandmother Vida’s, who cooked simply: baked beans and pickled vegetables. I ate them and I liked them very much. At Grandmother Vida’s, there was a big basement where the pickled vegetables were stored. My grandmother made fine pickled vegetables. She took those round fleshy peppers and filled them with parsley, carrots, cabbage and so on. There was sauerkraut, too. I really liked the pickled vegetables and the beans she baked. Grandmother Vida cooked it in an earthenware pot. She used to put it under the stove, it was a very primitive stove, and it stayed there until noon in the heat and formed a crust.

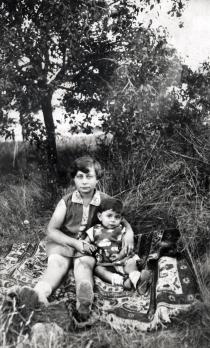

First, I had to go to an infant school. [The last year in the kindergarten, where children are prepared for school.] This was before the Jewish school. I even have a photo from the infant school. We had a very nice teacher; she just recruited the children. She recruited me too. In order to go to my grandmother’s I had to pass by the school. Once I was walking towards my grandmother’s and the teacher stopped me and said, ‘Come on, Mati, come study in our school!’ ‘No, I can’t. I’m going to see my grandmother.’ And so I passed by the school, I didn’t want to go there. But eventually the teacher recruited me. And I liked it so much that I even became ‘the boss’ of the infant school. There were around twenty children. We weren’t taught reading and writing. We were led to the nearby hill to play games. There were two hills near Karnobat: Dedo Dimcho’s hill and Kakkazan hill that means ‘Hill of the 40 cauldrons.’ There was a myth that a big bey [Turkish title] had buried his gold there. Then they tried, but with no success, to plant a forest on it. It’s a lilac garden now. We made great efforts in the past: we had brigades that went there, digging and planting trees. We didn’t plant lilac but something else then.

I went to the Jewish school. There were only two rooms in the Jewish school: the first and second grade studied in the same room. The result was that when I was studying in the first grade I listened to the second grade lessons as well. So officially we finished the first grade but in fact we ‘finished’ the second as well.

My first teacher in the Jewish school was very good: a Bulgarian, but I believe she was of Greek origin. In Karnobat there were Greeks, but they didn’t recognize themselves as Greeks, but as Bulgarians. She was a little plump; she was very nice and was married. When somebody couldn’t answer some question, I answered and then she sent me out of the classroom. It happened often and one day I felt cold and went back home.

I loved all the subjects but I was especially biased towards literature. I didn’t carry my textbooks back home; I knew everything by heart, so I left them at school. I just didn’t know what it was like to study at home. When at the end of the year they gave the certificates to us they even said I had the best results: ‘Here you are, Mati, it’s six [the highest grade]. But if there was a mark ten, I would give it to you.’ In the third and fourth grades, we began studying history and biology. We learned Hebrew. It was hard, the language was difficult. I coped with that too, but without any pleasure because it was difficult and it had nothing in common with Ladino. Ladino is a European language as it has some things in common with Spanish. I knew the [Hebrew] alphabet a little from Ladino; I could read but not easily. There was no one who could help me.

There were very good and nice teachers in the Jewish school. They came from Kazanlak: one taught us in Hebrew and the other in Bulgarian. At the end of the course, we had to have an exam. A commission from the Bulgarian school came to see what our preparation was and whether we were able to move to the junior high school. Some of us didn’t succeed; there were some really dumb pupils. There was a girl called Roza. The teachers asked me to help her but she didn’t even learn the alphabet. We finished the fourth grade with this exam and moved to the Bulgarian junior high school. So I studied Hebrew until the fourth grade, and it wasn’t very systematic. We had a teacher from Yambol; I always laughed at him and told at home what funny pompous words he had said in class. He always sent me out of the room, only for hinting.

My father [usually] came back from work late and it was a very pleasant moment for me. He was very loving, he immediately took me on his lap and began telling me what had happened at the ‘charshia’ [a word of Turkish origin, which means ‘marketplace’] how a stammering man there had carried around chickpeas and hadn’t been able to say ‘chick-peas.’ ‘When he finally manages to say ‘chick-peas’ the time for closing the shops comes.’ He was telling me about Uncle Milan from Sungurlare, how he had come and what they had been talking about. There was a businessman next to him at the ‘charshia.’ His name was Nikolay. So, this Nikolay had planted strawberries. In those times, we had seen wild strawberries only on the hills. Nikolay had planted them and he even brought a plate full of strawberries once.

My father didn’t have any specific political views; he had been a right-wing socialist [social democrat] in his youth. Even when he got married my mother laughed at him because he wore a red tie. She was reactionary. [She didn’t support the socialists and the revolutionists.] She had nothing to do with the socialists. But later, when my father became more sedate and started his business, he became a radical. My father said about Stoyan Kosturkov, who was the leader of the radicals, ‘He’s the leader of the artisans and retailers.’ And he redirected to them. When he was a right-wing socialist, I remember him going somewhere in a cinema’s little room where they met but it wasn’t illegal. It always happens like that: when you are young, you are a socialist. Later you become a reactionary.

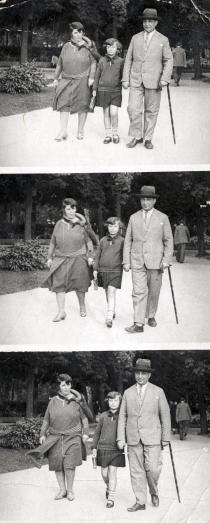

We didn’t go to the seaside. When I was a child, we used to often go to Bankya. [This was a small resort place in the past; today it is part of Sofia.] They say that when I was a child we went during the holidays to Tryavna, but I only dimly recall it. The air was better there. We went to Zheravna: there was a young shepherd there. I liked him and he liked me, too. He gave serenades for me. In the mornings, he passed by with his goats. He had a flute and played it and I stood at the window and watched him. I remember that once we went to Hisarya. [This is a Bulgarian mountain resort, famous for its healing mineral waters.] My mother took therapy there; she had high blood pressure.

Actors from different companies used to come to Karnobat. I remember Gendov; he had a traveling troupe. We often used to go to the old cinema, and then the community center was built. My father took me to the cinema where the silent films still existed then. Gendov used to come often with his wife and the troupe. They were very poor. People said that Gendov’s troupe used to rob the central shops when they came and always left debts behind, which they never paid off. But people weren’t very impressed; they knew it would be that way. We went to the theater regularly, but after the performance we hardly went back home along the dark streets. We couldn’t even think of transport then. I hadn’t seen a car in Karnobat. There were no cars. There were only carriages and some covered cabs. I think they were called ‘lando.’ We ordered a carriage in the evening when we had to travel because the railway station was a few kilometers away. We went to the cinema on foot. Sometimes I went to the confectioner’s with my parents. We sat at the table and were offered cakes and tarts from a big dish and everybody took what he or she liked. That’s how the tables were served.

I remember that we bought a radio around 1930. There was no radio in Karnobat and a man came to the cinema to show us what a radio set was. Until then, we heard the news only from the public crier. He came, beat the drum and said, ‘Tonight a man will come to the cinema who will show you a radio.’ So we all went to the cinema that evening. We bought tickets, the man entered, a table was brought in and he said, ‘Now I’ll tune in to a radio program from wherever you want: from Sofia, from Bucharest, from Istanbul.’ And he started turning a button. The radio started crackling, it crackled and crackled, but it wouldn’t transmit anything. The man went on turning the button but it still crackled and we became sick of it. My grandmother was the first to say, ‘I can make these popcorn cracks at home as well.’

She had a special pan for making popcorn. It was like a little drum with handles: she put the popcorn in the drum and put the drum on the brazier; it was made of iron and with four legs. She put charcoal in the middle and a grate upon it, and so she made popcorn. The man looked around and said, ‘If you leave, I’ll give back your money.’ So we didn’t see what a radio was but my father got interested in it and decided to buy one. He went to Sofia and brought home a radio. It was something unique for the whole neighborhood. They all came to us to listen to the radio and the old women asked if there was someone inside. When I told them there was no one they wondered, ‘How is it possible that it’s singing without anyone inside it?’ It was almost as big as a television. My father was very keen on it; he always searched for stations and listened to music from Istanbul. A Sofia station could be heard, too, but the signal was weaker. When different people came by, they asked, ‘Mati, is that you singing?’ I replied, ‘No, I can’t sing.’

There were balls at different occasions. The rabbi lived in a big house with a big hall where soirées took place. People danced quadrille, ‘Ladies change,’ and we, children took part only in the preparations. Then we, two or three girls, went to bed. There was, if I might say, an elite part of the Jewish quarter, which used to gather.

We went to the synagogue regularly. Mothers didn’t do it as often as the children. It was interesting. The rabbi sang and in a moment, the sexton would say, ‘Rise!’ and we stood up. Then he would say, ‘Sit down!’ and we sat down. We found that interesting. We didn’t know what happened but we were told what to do. We, the children, used to sit on some marble seats. There was a separate section for women. The men were in the lower part and sang from time to time; people used to collect money for the poor and for the synagogue in a very discrete way, the richer ones gave money too. Grass grew all over the churchyard and a mulberry tree stood there. We climbed on it and gathered mulberries during the day. We did it every time when we visited the synagogue. My father didn’t like going there too often; he wasn’t especially religious.

I vaguely remember my two aunts’ weddings. They married men from other cities: one was from Kyustendil and the other from Sofia. I was a bridesmaid. I remember we went to the synagogue where they stood under something like an arch. I held the trains at my aunts’ weddings. They weren’t big weddings.

I started studying in the junior high school in 1931. My first friends were from the junior high school’s first grade. We had a teacher for every single subject. I became very keen on literature because I had a very good teacher: Mrs. Todorova. She was a war widow, she had two sons and she helped them graduate as a lawyer and an engineer only with her teacher’s salary. She held firmly to Bulgarian and to orthography; I knew the old orthography perfectly. We had spoken before in the Eastern Bulgarian dialect, but at that time we started speaking in Western Bulgarian. In fact, Eastern Bulgarian is the correct Bulgarian.

We were taught in Bulgarian both in elementary school and high school. The geography and biology teachers were good and all the teachers’ staff was good. I didn’t like gymnastics. We were two ‘anti-sport’ girls in my class; the other girl had excellent marks [grade 6, which was the highest] in all subjects and was in the first position. I had excellent marks in all the subjects but I had a four in gymnastics, so I was in the second position. I couldn’t do well in gymnastics, that’s all. I was plump and slow and that spoiled my marks. Sometimes in the mornings my father used to test me, ‘What have you got today? Tell me the lesson immediately!’ I told him the lesson and he said, ‘Come on, you’re going to have a four and that’s all.’ I went to school and thought, ‘Fine, a good mark.’ I was examined and received a six. So I said to him, ‘You always underestimate me. Look what marks I receive at school.’ There was a library [in Karnobat] I had read all the books. I liked reading. My father read, and my mother read romance novels.

I graduated from junior high school in Sofia. When I was in the second grade, we moved to Sofia. Instead of sending me to Sofia on my own, my father found a job here so the whole family moved. We: my mother, my father and I, came to live in this apartment in 1932. My grandmothers wouldn’t leave their gardens. My father’s brother lived in an apartment next door. At first, my father worked with his brother, but later he opened a perfume shop on Lege Street with his sister’s husband and another man. They sold perfumes and crystals. In the meantime he was a ‘painkiller’ in a textile factory, which was at that time in a suburban area that’s now part of Sofia. He was an accountant, an organizer, and a work mover. The owners, I believe one of them was a Czech, relied on him a lot because they couldn’t do without his work. He walked there every day; there was transport only to ‘Orlov most’ Square then. He said that sometimes Prince Kiril’s driver took him in the car.

Of course, I felt pity when we moved to Sofia. I felt nervous that there were no hills in Sofia and there was no place where I could walk around. And the hills [in Karnobat] were all covered with almond trees. In the spring, the trees bloomed wonderfully. Sofia children weren’t better than I was, especially in literature. They all used a pompous style; a fact that made me anxious and I couldn’t understand why they spoke like that. I spoke in a different style. They didn’t laugh at me for speaking in a different manner because they knew it was the correct way. The Bulgarian teacher always emphasized my good style.

At some point I contacted a Jewish organization that was something like a leftist scout organization. Its name would translate as ‘The Young Guardian’ [This is the Hashomer Hatzair Zionist youth organization 4]. I became friends with some Jewish girls. I also became friends with Bulgarian girls in the high school. There was a Jewish junior high school in Sofia but I wasn’t ready for it, since there were only three grades in the Jewish school in Karnobat, and I went to a Bulgarian school. It was in October 1932. Some boys asked me, ‘Girl, what are you looking for? ‘I would like to enroll.’ ‘Well, go to the headmaster.’ So I was enrolled in the class E. And there I graduated from the junior high school.

After I graduated, I left for Paris. My mother laughed because I didn’t know French. I spoke only German; I had studied it in high school. I began learning French in Paris. There was a three-month course called ‘Pantheon’ where I began learning French. I studied really hard; I had really good written French. When I came back, the fact that I could speak French didn’t help me at all.

I liked medicine very much. My mother was never healthy, she used to take a lot of medicines and I became keen on medicine but when I was told that I would have to see dead men, I gave up. My father advised me, ‘Well, then enroll into French philology. What will happen then? You know that a Jew won’t be accepted as a teacher.’ There were no Jewish teachers indeed. My mother wanted me to study chemistry. I have never had a mark lower than excellent but I wasn’t especially keen on it. Well, I enrolled into chemistry but when my mother left for Bulgaria several months later, I moved to the Sorbonne and enrolled into Archeology and History of Arts. I had just returned for my holidays when the war began.

I spent a year in Paris and it was the best year of my life. The landlady was very strict; I lived at her place just for a while and later I took a separate room. It was very interesting there. I used to go out on the street at sunset and I watched Paris life; it was wonderful. I was a beautiful girl and people were very tolerant and accepted everything; I was from the Orient. However, I immediately turned towards the Bulgarians there. I was in the subway and two men, standing behind me, were talking, ‘Shall we try talking to her or not?’ And I turned, and said in Bulgarian, ‘No, you won’t talk to me, I’ll talk to you!’ So, they told me where the Bulgarians met. They were a great company. It included Iliya Beshkov, and Nenko Balkanski, an artist called Popov. [These are all eminent Bulgarian artists.] There was a little restaurant, which worked as a canteen also. Popov had painted it all. Stefan Sarchadjiev [a distinguished Bulgarian theater director] was there on a specialization. The great director, Krastyu Mirski, was studying there too. There were more modest people as well who had left Bulgaria because of their leftist political orientation. The company was really nice and we got together every evening.

In Sofia I had a good company of girls, friends of mine. They were all Jews. All of them were university graduates: engineers, dentists, etc., and we had all been friends since our high school years. I met my husband, Nisim Levi, in that company. He was the only one in that circle who had graduated in medicine, and who was sent to different villages all the time. We used to write to each other regularly. It was like that for three or four years; we were always separated, up and down the country. He was a Komsomol 5 worker in the villages of Kesarevo, Kilifarevo, and Dobromirka. He was enthusiastic about the Komsomol work. He continued his work in the villages after 9th September 1944 6 and then he was sent to Sofia. He started working here. We got married in 1945. Civil marriages before the registrar were introduced then.

I didn’t get married according to the Jewish tradition and my husband and I even decided to have a wedding without any ceremonies. There were no clothes, nothing. There are Jewish women who know the Jewish rituals but I’m not acquainted with it. Our wedding was very simple. I borrowed a dress of my mother, which was red and a little bit nicer than the others I had, and we went to the registrar. We couldn’t even do it on Sunday; it was Monday then. We went to a pastry shop with two friends, and then in the evening my mother killed a couple of chickens and cooked them and some people helped with the cooking. There was no other meat in those days. We ate chicken with rice and some cake; it was a very simple party. We gathered right here in this apartment but there was a door and the space was turned into a big hall.

In the beginning, we lived with my parents, then they died and then we lived with our children. We lived in Sofia during the Holocaust. There was another block of apartments opposite ours where a woman called Michkuevska lived. She was a tailor and lived with her parents. She had a fine apartment but she decided she wanted to have our apartment and we had to leave. That was before the Jews were interned in masses 7 and there was no [yellow] star 8 yet. She decided this and she made us leave. One day a man came here and said, ‘You’ll have to leave, because a lady from the palace wants to live here.’

We were among the first people who were driven away. We went to my uncle’s place. When restrictions for Jews to live in the center of the city were accepted, we were sent to live beyond Hristo Botev Boulevard; that was the boundary. Our family was ordered to leave for Pazardjik. We were about to be interned there when an order from my father’s bosses came stating that the factory couldn’t function without him and he had to be mobilized to return here, so we came back, but in the other quarter. Probably we could have taken some steps to get back to Karnobat, as we would have been allowed.

Air raids here were really horrible. I believe the first bombing was on 31st January 1944. Then there was another on 30th March and several smaller ones between these two. We lived at my uncle’s place and he was very curious. When an air raid was about to begin, he called me, ‘Mati, come to the roof and see how the entire Sofia is lit up.’ Sofia looked really beautiful. Then we walked in the ruins and jumped over the ditches.

We came back here after 9th September 1944, but my father couldn’t cope with many things. We came back to our old apartment. We were told that nothing could be done because she [the neighbor who had taken their apartment] was a worker. She was also a king’s woman; she was indeed a king’s woman, because her mother had been Ferdinand’s lover. She was a very refined lady, with a small hat with a veil on it, always on high heels. Her husband was an army officer. She used to say, ‘I’m a worker.’ She sewed complicated things. We did nothing bad to her, but she was very unpleasant. She left a great mess in the apartment but in the end she left it.

I couldn’t graduate from Law. I finished all the semesters because I had friends who signed my student’s book for me but I couldn’t go in for the examinations because I was a Jew, but I passed most of the exams. I enrolled into a course in Russian, sometime after World War II, and then I taught in different institutions. I know French. I spoke German because I studied it in high school.

At some point, I cannot remember the year, I moved to accounting. After I retired I worked for another ten years. First, I became a guide of Russian tourist groups. I traveled all over Bulgaria with the Russian groups and it was very interesting for me. I have seen unbelievable drinking-parties. Russians drink remarkably! On the next day the person in charge used to collect them and scolded them and they were so quiet. Then, for some time, I looked after my grandchildren but I was still working.

My elder son, Roni Levi, became an associate professor in mathematical analysis. I think he has inherited his talent from my kin. He had the best results when he graduated from high school. He was the most competent student in mathematics in the school. He was always absent, he always wandered somewhere. He should have been expelled because of the high number of absences but how could they do without their best student! My other son, Yosif Levi, works in the Bulgarian Academy of Science. He learned English in high school and started working as an interpreter. Now he’s engaged in it. He translates books. My two sons have two children each. One of the grandsons went to America. The second went to Israel and the third studies in Japan. One of my daughters-in-law, Mila Kozhuharova, is a doctor: an epidemiologist. The other one is already a pensioner.

Glossary: