Leya Yatsovskaya

Vilnius

Lithuania

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of interview: February 2005

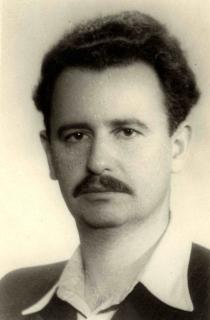

I met Leya Yatsovskaya at the United Jewish Community of Lithuania, where she works as an accountant. I didn’t have to talk her into giving an interview, she gladly agreed to it. Leya is a beautiful elderly woman with arched eye-brows, and beautiful bright eyes. She is still attractive. When I saw her pictures, I acknowledged that she was a real beauty. I was in Leya’s house. It’s a small, two-storied mansion ‘tightly pressed’ to the other neighboring houses. There are no homestead lands or front gardens in Vilnius. There are a lot of shoes by the large staircase to the second floor. Leya’s daughter and grandchildren live there. Her sons have their own apartments, but their children come over here as well. The house is very cozy. There are paintings of Leya’s children on the wall. All of them are artists. The hostess asks me to sit at the table in the cozy kitchen. To begin with she treats me to imberlach. Unfortunately, she has very few family photos left. She didn’t manage to preserve them in the war years. I liked the story of a poor girl from a Lithuanian town, who managed to overcome the hardships of war and start a wonderful family.

The Soviet invasion of the Baltics

My family background

I was born in the Lithuanian town Ukmerge. During my childhood and adolescence the population of Ukmerge was about 12,000 people, and 5,000 out of those were Jews. Therefore, Ukmerge can be really called a Jewish town. My parents were from Ukmerge and as far as I know their ancestors, too.

My maternal grandparents, Toybe and Leizer Treivsh, were truly religious Jews. They were born in the middle of the 19th century. I didn’t know Grandfather Leizer; he died in 1919. I was told that he read the Torah and Talmud all day long. He prayed and went to the synagogue. Grandmother Toybe did all the work. She was the bread-winner. My grandmother baked bread in a large Russian stove 1 and sold it.

Apart from work about the house and baking, Grandmother Toybe had to bear, feed and raise the children. There were five of them: two daughters and three sons. In the early 1920s, the children became adults and left the house. This made Grandmother Toybe sad, and then she got ill and went to Vilnius, where her younger son Haim and daughter Fanya lived. Before 1939 Vilnius belonged to Poland [see Annexation of Vilnius to Lithuania] 2, so we happened to be in different countries: we were in Lithuania, and my grandmother was in Poland. That’s why I don’t remember my grandmother. I know she died in Vilnius in 1930. My mother’s two elder brothers, who were born in the 1870s, were pharmacists. One of them was called Azriel and the other David. They both lived in Ukraine, then USSR, in some small towns, where their wives were from.

During the Great Patriotic War 3 both my uncles remained in occupation with their wives and children. All of them perished during the mass actions against Jews. I never met neither them nor their children. I don’t know their names either. Another one of my mother’s brothers, Haim, the youngest, born in the 1890s, lived with his sister Fanya in Vilnius, on Nemetskaya Street. Haim was single. He was about 50 when World War II was unleashed. I don’t remember Fanya’s husband’s first name or surname. All I know is that they had one child: a son, who was about ten before the outbreak of war. Uncle Haim, Aunt Fanya and her family became prisoners of the Vilnius ghetto 4 and perished.

My mother was born in 1883 in Ukmerge. She was given a rare Jewish name: Rayne. I don’t know exactly what kind of education she got. I think it was elementary. But still she was literate. She knew how to read and write in Russian, Polish, Lithuanian and Yiddish, and rudimentary mathematics. She helped me with that when I was in school. Her mother tongue was Yiddish, which was common for most of the Jewish population of Lithuania. Before getting married, my mother helped Grandmother Toybe about the house. I don’t know how my parents met. I don’t think it was a pre-arranged marriage though.

All I know about my paternal grandparents is that they were from Ukmerge. They died long before I was born. My father was much older than my mother. His parents were born in the 1840s. My grandfather’s name was Abram Faingolts. I don’t remember my paternal grandmother’s name. My paternal grandparents died in Ukmerge in the 1900s, long before World War II, and were buried in the local Jewish cemetery, which was closed in the post-war period. My father had siblings, and his younger sister Mikhle was the only one I knew. She lived in Vilnius with her husband and two daughters. All of them died in the Vilnius ghetto. My father’s brother, whose name I don’t remember, left for America with his family in 1923. We didn’t correspond with them. I don’t know what happened to them. I don’t know anything about my father’s other siblings. I’m sure that my paternal grandparents were religious.

My father, Mane Faingolts, was born in Ukmerge in 1867. Like all boys from poor Lithuanian families he went to cheder, where he got rudimentary knowledge. He didn’t go on with his education. My father did hard physical work. When he was young he was a house painter. When he got older he worked in a workshop where lemonade was bottled. It was hard labor. My father stood in water and cement, in a damp and cold environment.

Growing up

My parents got married in 1907. Of course, the wedding was in accordance with all the Jewish traditions: under the chuppah, which was mandatory back in that time. In 1908, my mother gave birth to my elder sister Dora. Then there was quite a big gap and in 1916 my second sister Riva was born. Then in 1918 my mother gave birth to Malka. Our family was poor and when my mother got pregnant at the age of 37, my parents decided to leave it like that hoping that a boy would be born, but then my mother gave birth to me. My mother felt so ashamed that a fourth daughter was born, that she told my father not to go outside so as to avoid the questions of the neighbors. I was born on 25th October 1920. I was named Leya, in honor of my deceased grandfather: Leizer.

Our family lived in my maternal grandparents’ house. My grandmother left for Vilnius and we were then the true hosts of the house. I remember my early childhood; since the age of three. As far as I remember, my mother, Aunt Fanya, who lived in Vilnius, and I, were drinking cocoa from beautiful blue cups. Aunt Fanya had a white and brown checked dress on. I think that’s my first recollection of my childhood. A little later, I was settling down in the house and, of course, my recollections from childhood are connected with that.

Our house was on the street called Synagogskaya [Synagogue Street]. A big synagogue wasn’t far from us. Then, in the1930s, our street was renamed Rybnaya [Fish Street]. My grandmother’s house was one-storied with an attic, which we always leased out. Our family was very poor and we wouldn’t have made it without the money derived from leasing. Like most of the apartments in Lithuania, our house was of a longitudinal layout: there was a hall from the entrance, then a kitchen, followed by a small bed-room partitioned from a drawing-room, which was used as a dining-room. There was a door in the dining-room opening to the yard. There was a big Russian stove in the kitchen, where my grandmother baked bread for sale. There were shelves in the hall, where she put freshly baked bread. There was also a bell in the hall. Visitors rang the bell when they entered the hall because at that time doors weren’t locked. We thoroughly insulated the door of the dining-room with blankets and the like as it was cold in winter time. There was a tiled stove in the room, but it required a lot of firewood. We didn’t have any, as it cost a lot of money and my father couldn’t provide for it.

To save firewood, my father made a stove himself from a sheet of iron. Its chimney joined the fixed furnace, but that furnace was clogged and emitted a lot of smoke into the room so this made it difficult for us to breathe and see. It hurt our eyes and we asked not to heat the premise as it was better for us to stand the cold than smoke. Malka and I shared one bed. Before we went to bed, my mother warmed our blankets before the stove. My sister and I got our clothes off quickly and my mother covered us with the warmed blanket. My parents, sisters and I, all shared one bedroom. We had beautiful furniture, inherited from my grandmother together with the house. There were large wooden beds, and a large wardrobe, which was in the bedroom. A beautiful carved cupboard took the larger part of the dining-room. My mother kept linen in the three bottom drawers. There was a flap board in the cupboard, which we used as a desk. There was a tea set on the top shelf. The above-mentioned blue cups were part of the set. A chandelier was made from a kerosene lamp, so the room was hardly lighted.

My mother did all the household chores with the exception of laundry. We had a large family and didn’t even have running water, so my mother gave our linen to the laundress. We had to walk up the hill to get water from a pump, and for the toilet we fetched water from the River Shvenchena [in Russian it means Holy]. Usually the deaf and dumb poor Jews brought us water, but Malka and I did that as well. I liked it when there was a lot of water, so that I could fill up the water barrel. My mother was a wonderful cook. She made delicious dishes from inexpensive products. Potato and herring was the most common food for poor Jews in Lithuania. There was a shop not far from us where only herring was sold. Usually there was fresh herring, and herring which had been salted the previous year, which was twice as cheap. My mother bought the cheaper herring and we ate it everyday. Even now I consider herring and potatoes to be the tastiest food in the world. Sometimes we had soup. In winter time we had it with grain, and in summer with vegetables.

In summer it was easier for us as lemonade was in demand and my father received a certain percentage of the sales and made pretty good money. My mother had been saving all week long to lay the Sabbath table: we had gefilte fish on Saturdays no matter what. There was a lot of fish in Ukmerge and it was cheap. I still cook fish the way my mother taught me. At that time usually pike was stuffed. The fish was disemboweled, and cut into large pieces. Then, fillet was removed from the back. Fish meat was minced. Then croutons, onion, salt and a little black pepper were added in the mince. Then it was added to the remaining pieces of fish, from which fillet was taken. Vegetables were put in the pot: onion rings, carrots, then fish and then vegetables again. My mother didn’t use beet. All that was sprinkled with salt and put in the oven for a couple of hours before the fish bones turned soft. Tsimes 5 was a frequent dish on Saturdays. My mother cooked it the following way: she boiled fat beef, put there a lot of peeled and sliced carrots. That mixture was boiled, and then kneydlakh were added. Those are small dumplings made of flour, chicken broth or goose fat, egg, onion and salt. When there was no meat, my mother cooked carrot tsimes without it, and it was still very delicious.

My sisters and I helped my mother get ready for Sabbath. On Fridays we cleaned the house thoroughly, put a clean table cloth on our dinner table, dusted the rugs, furniture and cleaned the floors. Besides, my mother cooked dinner for Friday night and Sabbath. On Saturdays Jews weren’t allowed to do anything, even fire a stove, warm food, or put lights on. Talks about work were forbidden. I remember a joke since childhood: A Jew went on Sabbath to his neighbor. They were sitting at the table and chatting. The host said, ‘If it wasn’t Saturday, I would say: Ivan, warm the samovar.’ The joke is that Jews are forbidden to talk about work on Saturdays. Ivan wasn’t Jewish, and he did all the work for the Jews on Saturdays [shabesgoy]. We didn’t have any extra money to pay somebody else. On Saturdays, the children did everything: first my sisters, then I. It was considered that it wasn’t sinful for children who hadn’t come of age, boys no older than 13, and girls no older than twelve, to do simple work on Sabbath and holidays.

There was a baker, who lived not far away. On Thursdays all the Jewish ladies from the neighborhood baked challah, fancy bread in his bakery. Each of them brought their own dough. My mother took pride in her challah, which was the longest and tastiest. On Friday, the challot were taken out of the oven and the Jewish ladies put chulent, Sabbath food, in the oven for it to be kept warm. Each hostess had her own pot which she took to the baker’s. My mother usually cooked chulent with meat, potatoes, onion and beans. When we had enough money we had chicken on the Sabbath table. On Friday evenings, freshly baked challah was put on the table and candles were lit. There was kosher wine on the table as well. Before the evening came, my mother said to me that it was time for me to put on a dressy outfit. I had only one dress like that.

When my father came back from the synagogue, we sat at the table and my mother, having a trendy laced head kerchief on, put her hands on her eyes and read a prayer. Also on Saturdays, my father went to the synagogue, and I often accompanied him and carried his prayer book. Usually my father went to a small prayer house, which was close by. He attended the synagogue on holidays. The synagogue was two-storied, but the first story was in the basement. The men had to walk downstairs. When I asked why the first floor was so deep, one of the old Jews said that it was done for the synagogue not to be taller than the other buildings, so that the Jews wouldn’t be envied. I enjoyed going to the synagogue with my father and look at the Jews with tallits and tefillins. Being a young girl I was in an elevated mood when I went to the synagogue. The building of our old synagogue is still in Ukmerge. Unfortunately, it was converted into a gym during the Soviet times, and didn’t change afterwards. There were hardly any Jews in Ukmerge after the war.

The kashrut was observed in our family. I tried pork for the first time when I was an adult and lived in Kaunas. We never had pork in our house. Kosher meat was sold in special Jewish kosher stores. My mother sent us to the shochet, when she bought chicken. He tied the legs of the fowl, cut it and then suspended it by the legs on special hooks and then gave us the chicken when blood poured from it in a special tub. We had separate dishes for meat and milk: from hardware to pots, pans and rags.

We were rather poor, though we weren’t starving. We wore the clothes of our elder sisters. So I had pretty worn out clothes. My mother made most of the clothes herself. She was good at everything. In 1925, my eldest sister Dora left for Kaunas. She finished the Teachers’ Training School and became a teacher. Dora got married and her marriage was a success. Her husband, a Jew from Kaunas, Srol Moskovich, was a well-bred businessman. Having finished school, Riva left for Kaunas as well. She finished a medical school there and became a nurse. Riva worked in a Jewish hospital in Kaunas and lived with Dora. Dora helped us a lot. She often sent parcels to my parents. On holidays she always sent presents. That’s why I always looked forward to the holidays. I always got presents from my elder sister. Pesach was my favorite holiday. There was a large chest with kosher dishes in the attic. My sister and I climbed up there to get the dishes on the eve of the seder. There was also a box with ancient books. One of the thick books was with pictures, and there was a beautiful girl in a pink dress with a bow, on one of them. Every year my sister and I looked at the picture and couldn’t help admiring the girl. We probably envied her a little bit because she was so beautiful and fashionable.

We only had table porcelain dishes. Pots and pans were pig-iron. Malka and I took them to the river and thoroughly scrubbed them with sand. Every corner of the house was immaculately cleaned. The furniture and floors were polished, clean tulle and curtains were hung, the paschal white-starched tablecloth was taken out. Later, our sisters came from Kaunas with presents. In my early childhood we were together. We put on stylish things. My father reclined at the head of the table on the first day of seder. He also dressed up. He didn’t have any festive garment. He just wore a clean starched shirt. He hid the afikoman under the cushion. Usually I was the one who had to look for it and find it. I also asked my father the questions [the four traditional questions at Pesach], which he answered and then carried out seder. Though we were poorly dressed and our parents couldn’t afford to buy presents for us on holidays, the festive table was full of dishes, which even rich people didn’t have, as my mother was the best cook. Shortly before the holiday, my mother bought the best chicken at the market. Besides, she looked at their bottom to see whether they were fat enough. She also bought goose fat. She bought a minimum of 240 eggs. She looked at each egg in the light. She always did it patiently.

Long before the holiday honey wine was made from hop. It was in the bottles covered by gauze in several layers for the chametz not to fall into it, God forbid. Of course, the matzah which my father brought from the synagogue in the basket, covered with a clean bed sheet, was the main food. We ate it instead of bread and made keyzele, cookies and cakes. Every day during the Pascal period we ate eggs fried on goose fat, with matzah. It was delicious. Apart from traditional gefilte fish, chicken and chicken broth with matzah kneydlakh and all kinds of tsimes and stew, there were also desserts. Imberlach is a dessert cooked as follows: carrots, ginger, sugar and orange peels are stewed for a long time until it gets thick. Then it’s spread on the board and cut after the mixture cools down. There was also angemach. It was made from sour beets with nuts. Beets were pickled before Pesach. My mother also cooked Pascal borscht from those sour beets. We ate it with matzah. On seder night we put a goblet with wine on the shelf in the hall. The wine was meant for the Prophet Elijah. The door to the hall wasn’t locked. When I was a child, I believed that Prophet Elijah really existed and that he went over to every Jewish house. Other holidays were marked in our family as well, but we didn’t prepare for them like for this one, so I don’t remember them that well.

My parents fasted on Yom Kippur, and went to the synagogue. Then my mother made a festive dinner. As for the fall holidays, I remember Sukkot because my father put a sukkah outside, by the house. During the holiday my father ate there, and my mother either joined him or stayed in the house with us because in Lithuania it was rather cold and rainy at that time. I liked to go to the sukkah and join my father. On that holiday my father bought me little colored flags. There were special Jewish little flags in Ukmerge. Jewish lyceum students walked around with them in the street. No matter how hard life was, during Chanukkah my father gave us money and gave each of us little presents. My mother baked scrumptious potato fritters, and fried patties in oil. There was a pageant procession along the town on the most mirthful holiday of Purim. When I started school, I also took part in it.

Since early childhood I got parental love. My father liked me more than any of my sisters. He said if he had two houses, he would give them both to me. He couldn’t imagine a greater richness. He paid more attention to me than to anybody else. He told me interesting stories, and sang songs. I still remember one of them which he dedicated to me:

You are as beautiful as Greta Garbo,

The most gorgeous woman in the world,

You are as beautiful as Greta Garbo,

But you don’t have as much money.

Our town, Ukmerge, was a Jewish cultural center. The center was mostly inhabited by Jews. We liked to stroll in the downtown area, at the square with the fountain. The inhabitants of Ukmerge liked to saunter there in the evenings. The majority of the Jewish population was poor and middle-class like us: I didn’t consider us to be poor. Jewish traditions were strictly observed among the poor and their violation was unspeakable. I remember, in the late 1920s, a Jewish girl fell in love with a Lithuanian and married him without her parents’ blessings and left for another town. The entire Jewish community in Ukmerge was simmering with rage. When the wrath was finally mollified, and the parents forgave the girl, they had to see the newly-weds stealthily as to not disturb public peace.

The synagogue was the Jewish center of the town. People went there on holidays and Saturdays. All the Jews of the town went there without any exceptions. They went there not only to pray, but to communicate and find out about the news and rumors. There were rich men in the town, though they were very few. They were owners of stores. Jewish stores also were in the center. There was a book store, owned by Koltun, not far from us. Murschik owned a shoe store. There were manufacture stores belonging to Ryshanskiy and Katz. The jewelry store, where gold pieces were on offer, belonged to the wealthiest merchant: Joffe. Doctors also lived in the center. A pediatrician lived close by. He was also involved in social activities apart from his work. That doctor treated us and other poor Jews for free and his wife, a dentist, treated my mother’s teeth for free. In winter I often went to her to borrow some skates. She never refused me as I didn’t have my own skates. There were two Catholic cathedrals in the town, and one of them was in the center. The military orchestra went there and I went over to listen to them. There was an Orthodox church in the town as well.

There were other Jewish institutions in Ukmerge: Jewish health organizations and charity organizations. Educational institutions were considered to be in the cultural center of the town. There was a Jewish kindergarten. I didn’t go there as it was too expensive. There were two Jewish elementary schools in the town. In one of them the subjects were taught in Yiddish and in the other one in Ivrit. There were two lyceums which did the same. There was also a religious school, but none of my friends went there. When I turned six I went to the half-first grade, pre-school in modern terminology, of the Jewish school, where the teaching was in Yiddish. I’ll never forget that wonderful Jewish school. I remember my teachers with awe. They didn’t merely teach, they put their heart and soul in us. There were three teachers at school: Leib Morgenstern, his wife Shifra Morgenstern, and another teacher, Rivl Itskovich, and the school headmaster.

Mostly poor children went to this school. They were so indigent that Malka and I appeared to be rich as compared to them. The director managed to arrange free cocoa or tea and rolls for the children. Besides, orphans, who had nobody to take care of them, were given free clothing: pants, dresses, and boots. I still recall one case and I start crying when I go back to it. One of the girls from our school got ill and we went over for a visit. The indigence I saw can’t be compared with anything: earth floor, a tiny window stuck in the earth and the hungry eyes of many brothers and sisters. I’ll never forget that.

Having finished school I entered the Jewish lyceum, where teaching was in Yiddish. It was a private institution, where tuition had to be paid for. My father managed to get some subsidies for education of four of his daughters. My elder sisters Dora and Riva also finished that lyceum. Malka and I had studied there for several years. In 1933 it was closed down and we had to transfer to the lyceum where subjects were taught in Ivrit and we successfully finished it. We studied the same disciplines as we had studied in Yiddish. I studied Ivrit rather swiftly. I did well and got prizes and awards at the end of each year. We had to wear a lyceum uniform: brown dresses with aprons and white collars and caps with green visors. Dora sent the fabric for the uniforms and my mother made dresses for Malka and me.

There were great teachers here as well. It was wintertime. Once on Chanukkah we staged a performance under the supervision of our teachers. I took part in it as well. One time we staged the performance ‘Sleeping Beauty.’ I played the part of the princess, whom an evil sorceress enchanted for 100 years. We had beautiful costumes from ruffled paper. The performance was accompanied by a pianist, who played classic melodies. My father was sitting in the assembly hall and was crying from admiration, affection and pride for me.

I liked drama performances very much. I loved music as well. Our pianist, who accompanied our performances, showed me a beautiful world of classics, getting me to know the pieces of the world’s composers. I also knew Jewish songs of klezmer musicians. I remember one Chanukkah song: ‘Оh Chanukkah, oh Chanukkah, beautiful holiday, it’s so merry, there is no other holiday like that. Every day we play with a whipping top and eat hot potato pancakes.’ My father taught me a sad song about a Jew who went to America to seek his fortune. He didn’t get rich, but he was so homesick, missing his wife and son. The Jew asked the starlet in the sky to come and visit his house in the village, where they lived and tell his son to learn the Kaddish, because it would be needed soon. My father always cried when he was singing that song. I was fond of arts in general. Literature appealed to me the most. I was very good at languages. During my studies at the lyceum I learnt Lithuanian, German, Latin and English.

I had a lot of friends and almost all of them were Jewish children. I had different hobbies. Unfortunately, there was no Jewish theater in Ukmerge. At least there was a cinema. I liked movies a lot, but I couldn’t go to the cinema very often as we couldn’t afford it. Sometimes I went to the movies for lyceum students and school children as the tickets were cheap. In that period of time German and American movies were mostly screened. I don’t remember what they were about. All I remember is that those several movies I saw were funny comedies. We liked to go on walks along the central square and listen to the wind orchestra.

Back in that time the Lithuanian society was politically minded. Political passion didn’t obviate a small and calm Ukmerge. Оne of the groups was involved in ‘inoculation,’ propaganda and teaching of Yiddish and Yiddish culture. But I don’t have any information about such organizations as I just heard of them. The most common among Jews were Zionists, and those supporting Jabotinsky’s 6 ideas. There were also visitors from Sochnut 7, who got the youth ready for repatriation to the historic motherland. There were also underground communists in the town as well as all over Lithuania. Our family, including me, didn’t belong to any groups. I was inclined to ‘left’ ideas, more democratic and attractive for poor Jewish people.

In 1938 I successfully finished the lyceum. I didn’t mind to go on with further education, but my parents had no money for that. They had educated four of their daughters. By that time, all of my sisters had moved to Kaunas. Dora was married already, her husband wasn’t poor and she helped two of my sister’s: Riva and Malka, when they went to Kaunas. Riva stood on her own feet. She worked in the Kaunas hospital as a nurse. She was very beautiful, tender and feminine. She was a very good nurse. If there was an opportunity for her to continue studying she would have made a great doctor. Malka finished Kaunas Ikh Duh Arbet 8 school. It was a school for Jewish girls where they were trained in crafts. Malka finished that school and became a seamstress. She lived with Dora, but Riva rented a separate room.

All of us understood that I had to study as well in order to get a specialty, but there was no place to study in our town and it was decided in the family council that I should go to my sisters in Kaunas. I remember my saying good-bye. I had mixed emotions: on the one hand, I was excited to go to the city, study, work, meet new people, and have an interesting life. On the other hand, it was hard for me to leave my parents, especially my father, who couldn’t help crying when he saw me off to the big city. I was his favorite little daughter.

I lodged with Riva, slept on one sofa with her. Dora watched that I wasn’t hungry, if I didn’t manage to have lunch at her place; she gave me one litas for lunch. With that money I could by half a liter of milk, a roll and a piece of salted Lithuanian cheese. Kaunas really impressed me. It was beautiful and huge as compared to Ukmerge. I started looking for a job but it was impossible to find one without letters of recommendation. Then my sister decided to help me. Once, Dora had a talk with a rich businessman, who had a large warehouse. She talked about me, boasting about my capabilities and beauty. She even showed him my picture. The businessman said he liked me, but not for work. So, I remained jobless for three months and then accidentally found a job via one of the girls I knew. What really helped was the knowledge of English and typing skills. I did all kinds of work: maintained the documents, kept the office in order, ran errands around the town. First the owner paid me 50 litas monthly. I worked for a month and he appreciated my work so much that he raised my salary to 75 litas and in a couple of months to 120 litas.

I became materially independent. Now I could help my parents like my elder sister. I took advantage of any opportunity to send my parents parcels with food, presents, and money via any acquaintances from my hometown, who came to Kaunas. Now I feel that my assistance wasn’t enough, but my parents were happy that their daughters were on solid ground, got professions and were strong for them. Riva and I rented a better apartment now. I could afford many luxuries: theaters and cinemas. I went to the opera in Kaunas for the first time. There was also an amateur Jewish theater. I went there as well. We always attended performances of groups touring Vilnius or any other Jewish theaters.

I made a lot of friends, with whom the husband of my sister Malka kept company: a lot of interesting young people, Jews and Lithuanians. I was very pretty and there were a lot of admirers around me. Gradually I started admiring one guy, who with time became the closest person, friend, husband and father of my children.

His name was Evsey Yatsovskiy. He was born in Kiev [today Ukraine] in 1918. He came from an intellectual Jewish family. Evsey’s parents were from Kiev. Before the outbreak of the October Revolution [see Russian Revolution of 1917] 9 they moved to Lithuania to escape pogroms [in Ukraine] 10 and the communist regime. Evsey’s father, Jacob Yatsovskiy, was a real merchant, businessman, who knew how to make money. He did really well. Jacob owned a movie house in Kaunas, as well as a video library, which he founded with a Lithuanian companion. Apart from the cinema business, Jacob Yatsovskiy also represented some world-known Swiss firm, which produced lacquer and paint. Jacob donated a lot of money to charity and helped the poor. His wife, Maria, found another way to spend her husband’s money. There was a coup d’etat in Lithuania in 1926 11 and the nationalists came to power. Four communists were executed in the central town square. Touchy Maria was deeply impressed by that and she soon became a member of an underground communist organization. Maria easily talked her husband into contributing rather large amounts of money to the communist party. Maria and Jacob had two sons: Evsey, and his younger brother Alexander.

Evsey was a very gifted artist. He was late for the entrance exams for the arts department and he entered the construction department of the university instead. He was a great interlocutor. I liked to listen to his stories. It seemed to me he knew everything. In 1940, Evsey was drafted into the Lithuanian army. He served in Marijampole [50km from Kaunas]. On weekends he came to see me in Kaunas. He couldn’t stand not seeing me no longer than a week. I introduced Evsey to my parents. My father wasn’t very happy. He wanted a prince for his favorite daughter, but he turned out to be the heir of the owner of the movie houses. Even if I brought a real prince in the house, my father wouldn’t have approved of him, as he sincerely believed that nobody was worthy of me.

The Soviet invasion of the Baltics

On 15th June 1940, the Soviet army peacefully came to Lithuania [see Occupation of the Baltic Republics] 12. In Kaunas many people, mostly poor Jews, who had a hard living, had high expectations for the Soviet power. They welcomed the soldiers with flowers and cried out to them, ‘Bravo.’ Rich Jews were of different opinions and they were right. All private enterprises were nationalized soon after and its owners were exiled to Siberia. It was dreadful: streets, squares, and parks were empty. People lived in fear of deportation. All the same, a lot of people of all kinds of nationalities were exiled and most of them never came back [see Deportations from the Baltics (1940-1953)] 13.

Those who were connected with the Zionist movements were touched by repressions as well. The communists, who were in the underground, were assigned to high posts in the new state. Then it turned out that Maria Yatsovskaya actually rescued her husband and son. Her assistance was appreciated by the communist party. Shortly after the Soviets came to power, Jacob Yatsovskiy voluntarily gave all his property to the state and became the chairman of the Cinematography Committee of the Lithuanian Republic. Maria went to work in the Central Committee of the Party. The owner of my firm was exiled right away and I lost my job. Evsey’s mother, who treated me like her own daughter, gave me a hand. She helped me get a job as an accountant in the Central Committee of the Party. As a matter of fact, I worked there all my life. Both of us recognized the new ideology. I became a Komsomol 14 member, and Evsey became a political officer 15 in the invincible Red Army. We sacredly believed in everything the communists said, including the invincibility of the Red Army. I couldn’t help thinking of war, when in Western Europe and neighboring Poland fascism was thriving. But still we were calm as we firmly believed that the fascists would be utterly defeated by the Soviets at once.

During the war

In 1940 Dora gave birth to a daughter and my mother came over to take care of the baby. Malka also got married. Her husband was a Jewish guy, Shleime Atamuk. That summer Riva was going to have a wedding party. She was very close with her friend Birger. On 22nd June 1941, on Sunday, I was getting ready to meet Evsey, who was supposed to come back from his squad. Riva came back home from night duty and said that there were severely wounded soldiers and she thought that the war had begun. I went to see what was going on in the town. Hardly anybody could be seen. People were leaving Kaunas. The Central Committee of the Party, where I was working, provided an opportunity to make arrangements to evacuate its employees and their families. I didn’t think of myself. The first priority was to send my mother, Dora and the baby, who had turned nine months. I made arrangements for them to get on a train and then I started thinking of myself. On Monday, 23rd June, the fascists were right outside Kaunas. I had to leave. Both Riva and Malka left the town. I swore to myself that I wouldn’t leave my father no matter what. By the building of the Central Committee cars and buses were parked for the average employees of the Committee. I talked to some of them to go via Ukmerge. When I went over to my father, he was at a loss for words, feeling despondent. He didn’t know what had happened to us and my mother. He took his coat, but left his passport. I had to go back for his documents. We were on the road, and I didn’t say goodbye to Evsey.

We reached the Latvian border. There were Jews. One Jewish lady gave us tea and I was thinking that in a couple of hours she would also have to go in an unknown direction. I told the lady not to linger. We were placed in a village school. In the morning we were to take the train. At night the town was glowing. An oil cistern was set on fire at the train station and everything burned down to ashes. All the fugitives went on foot. My father, aged 74, and I were the last ones. It was hard for him to walk, but I decided not to leave him. We had been walking for a long time along some sort of railway station. Finally, we managed to get on the passing train with the fugitives heading eastwards. There was nothing to eat or drink. I wasn’t even hungry because of my strong emotions. Though, I was really thirsty. At the stations I was able to get some water. We didn’t even have any containers to fill with water. We didn’t think that we were leaving for a long time and hoped that in a week or two the Red Army would start attacking and we would be able to go back home. Though I was the youngest in the family, I was the only one who stayed with my elderly father and I felt neither panic nor fear of the future. We were lucky. We got off in Velikiye Luki [Russia, Pskov oblast, about 500km from Moscow] and accidentally met Malka and Shleime. Maria, Evsey Yatsovskiy’s mother, was also with them.

Further on we went with Malka’s family. Maria stayed in Velikiye Luki to wait for the news from her husband and sons. We went on the open coal platform. By the end of our trip we looked like stokers or miners, who had just left the mine. Our impression was aggravated by our looks as well. Half way we all lost some weight. It was the hardest for my father. In three weeks we reached Kirov in Ural [2000km east of Vilnius, Russia]. He stayed at the evacuation point for a couple of hours. We had a chance to take a shower and eat a bowl of soup. Then we were sent to a kolkhoz 16, named after Kirov, not far from the town. The chairman of the kolkhoz was a kind and good-hearted man. First all evacuees settled in the rural club. Then our large family was given a separate room. So we were together: Malka, her husband and my father. I, Malka and Shleime worked in the field. We gathered flax. The kolkhoz gave us some ration: flour, and the baker, one of the evacuees, baked bread for us. The chairman of the kolkhoz gave us butter. I was sure that the other people from the kolkhoz didn’t get it. We lived in the kolkhoz for two to three months.

Shleime, Malka’s husband, was actually the head of our family. My father wasn’t a decision-maker but he said that there was a construction site of a paper plant, evacuated from Leningrad [today Russia], not far from us, and there were openings for workers’ positions. We decided to move to that construction site. In fact, we got jobs there. I worked as an accountant in the office of the plant. There was a small village not far from the construction site. It was the exile area for political convicts from tsarist times. We settled in one of the houses. The hostess, a tall and tacit woman, treated us well. Though, when we got our wages and decided to buy a jar of nanny-goat milk from her, as she had a couple of nanny-goats, she preliminary poured water there. My father could immediately tell that the milk was diluted. She didn’t sympathize with us maybe because we were Jews, or mere strangers, urban pampered people. The first winter was hard for us. We hadn’t taken any warm clothes with us and had hardly anything to wear. We were suffering from hunger and cold and our optimism helped us get over it.

Shleime started looking for my sisters and mother via the evacuation inquiry bureau and he succeeded. Soon we received a letter from Dora. She, her husband, his brother, Еvsey Moskovich, and my mother were in Pensa [today Russia]. In early 1942 they headed in our direction. It’s hard to describe the meeting of my parents. Each of them had thought that they would never see the other again. They didn’t stay with each other for a long time. Misfortune came into our family. I still have twinges of remorse. It seems to me that my fault is that I wasn’t protective enough of my father, who was an ill and elderly man. When we were at work, he helped me about the house. The winter was severe and my father fetched water from the river, having to walk in the deep snow. He caught a cold and stayed unconscious for a few days.

I went to the construction supervisor and asked him to give me a horse. It wasn’t that easy. They only gave us a horse after a few days. It was too late when Malka took my father to the hospital. The nurse said that she had given my father an injection and he had asked whether he could take a nap. It was the last nap my father took. He never woke up. I also feel guilty of the way my father was buried. There was a frozen cadaver of some Lithuanian who had died from hunger in the firewood storage facility. He couldn’t be buried, as they couldn’t find a horse. When we came with a sleigh, they put two coffins on it: my father’s and the stranger’s. The corpse was so stiff that they couldn’t close the casket. It was a horrible scene. We mournfully followed the coffin and my mother was whispering some Jewish prayer. When it rains it pours, as they say, and it poured on that day. Right after my father’s death, all our men were drafted into the army: Srol Moskovich and his brother, Evsey, and Shleime Atamuk.

The only joy I had was that Evsey Yatsovskiy found me. His aunt, his mother’s sister, Sarah Glieman, lived in Moscow [today Russia] and was asked by Evsey to find us and she did via the inquiry bureau in Buguruslan [today Russia]. It happened while my father was still alive and Evsey sent him a parcel with tobacco. My father really suffered without cigarettes. Evsey helped us by sending money and parcels with food at times. He served in the headquarters of one of the squads at the leading edge.

In 1943, a new Lithuanian orphanage was opened in Konstantinovo, Kirov oblast [today Russia]. Employees, who knew Lithuanian, were in need. When we heard about it, we decided to move there. We walked past a couple of villages. Common Russian women gave us a warm shoulder: they fed us very well, and asked us to stay overnight. I will never forget their kindness. We arrived at the orphanage. We felt like home as we were from Lithuania and it seemed even warmer here. There were a lot of orphans: Jewish, Polish and Lithuanian. Some children had mothers, who were given some work by the orphanage. There was a homelike atmosphere. We didn’t feel like outcasts and tried to help each other. We were given work at once. Dora was employed as a teacher and I as an accountant. After some time Riva came. She registered her marriage with her husband while in evacuation, in Central Asia. He was drafted into the army and she followed him. She found a job in the orphanage as a nurse.

I received a letter from Evsey shortly after our arrival in Konstantinovo. He asked me to go to Balakhna, Gogol oblast [today Russia], where the Lithuanian division #16 was being formed. [Editor's note: The battalion was called Lithuanian because it was formed mostly from the former Lithuanian citizens, who were volunteers, evacuated or serving in the labor front.] Evsey was there and he was entitled to a vacation before leaving for the front. I packed my things very quickly. I was missing him so much, as I hadn’t seen him since the beginning of the war. I left quickly, but I didn’t arrive there fast. In Malmyzh [today Russia], I had been trying to take the train to Kazan [today Russia] for a couple of days, but my attempts were futile. It was impossible. I missed a lot of trains. Some marines helped me get on a passing train. I didn’t manage to get on the train in Kazan either, but finally I reached Balakhna. Therefore, it took me about eight days to get there. I didn’t inform Evsey of my visit so it was a surprise. Both of us were happy to see each other safe and sound. Evsey took me to the regional marriage registration office, where we registered our marriage immediately. We didn’t have neither wedding rings nor clothes or a feast. I didn’t manage to put on a wedding gown and veil like I had dreamt in my childhood. War had made its adjustments. I never regretted that I became Evsey Yatsovskiy’s wife. I stayed in Balakhan for three days. Then Evsey was to start work and he returned to his squad and I forced myself to leave for Konstantinovo.

I went back to the orphanage being a married woman, with a new last name: Yatsovskaya. Hardly anything changed in my position. I started getting more letters from Evsey. They were even more tender and affectionate. I also corresponded with my mother-in-law, Maria. By that time she was quite a dignitary: she was a plenipotentiary of Lithuania in Tartaria and Kazan.

Another year had passed. In spring 1944, my mother-in-law was transferred to Moscow and Evsey insisted that I should go there with her. So I turned out to be in Moscow with Maria. She facilitated me in getting a job as an accountant in the Lithuanian embassy. I was in Moscow for the first time. Of course, it would be hard to compare Moscow during war times with a pre-war capital. The windows were disguised. Many of them had paper bands in the form of a cross. Though the war was approaching the Western borders of the USSR, Moscow was still rarely bombed. Nonetheless, I enjoyed staying in the beautiful city. I attended museums, theaters, most of which returned to Moscow. Not all of them were operating. Many of them didn’t bring the masterpieces of the world art from evacuation. Even the things I saw there were enough for my reminiscences about Moscow. I made pretty good money and received a good ration. I had a chance to considerably help my family, who stayed in Konstantinovo.

After the war

I had stayed in Moscow for some months. In summer 1944 Lithuania and its capital Vilnius were liberated. My father-in-law left for his motherland immediately as well as the government. Like in the pre-war times he was assigned the head of the Cinematography of the Republic. In September 1944 Maria and I also returned to Vilnius. We had been roaming for a couple of months: renting apartments or staying with relatives. Evsey continued his service and was far from Vilnius.

I was immediately employed in the same position I had before the war. I resumed working as an accountant in the Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania. I managed to get an invitation letter for my kin rather quickly. In January 1945 I was meeting my loved ones: my mother, Dora, Riva and Malka. They didn’t have a place to stay and so they rented a small apartment. My sisters’ husbands were coming back from the lines: Srol Moskovich and Shleime Atamuk. The families of Dora and Malka got their own apartments. At that time there were many unoccupied houses in Vilnius: mostly Jewish, as their hosts had perished in the Vilnius ghetto, in Ponary 17 and other places of mass execution. Riva’s husband had perished in the lines. My Evsey still served in the army.

At the beginning of 1945, my husband was on leave for a few days. Then, many Lithuanians went to the forest with their guns. On the Lithuanian territory the war hadn’t ended, but now it wasn’t against the fascists, but against the Soviet occupants. Evsey was a communist and he was afraid that he would be killed. He wrote a letter asking for a vacation, where he openly wrote that he wanted to leave heirs in this world. We conceived our daughter during that short-term vacation. We felt so happy on 9th May, the Victory Day. We had been awaiting it for so many years. Shortly after that my husband’s parents were given a wonderful mansion in the center of Vilnius, and we moved there. I had spent all my post-war life in that house. I’m still living there. It’s a small two-storied house with a staircase inside with beautiful tiled stoves and a large kitchen, the place to live for our family. In 1945 I gave birth to my daughter. We called her Alexandra after my husband’s brother. Alexander was in the group of the partisans, which was catapulted to the forest in March 1942. A forester saw the traces in the forest and betrayed the group. Alexander and the other guerillas were shot by the fascists.

My husband was transferred to Vilnius shortly after Alexandra was born and continued his service in the headquarters. During the war, he joined the Communist party. I joined the Party in 1948. I can’t say I did it deliberately. I didn’t have the guts like many Komsomol members, nor did I have strong beliefs in the ideas of communism. I couldn’t have acted in a different way. First of all I lived in a family where communist ideas reigned owing to Maria, who was able to inculcate all the family members with them. Secondly, I worked in such a place where it was mandatory for me to be a member of the Party. I did that, as I wasn’t strongly against communism. Before joining the Party, I was asked a question whether I wished to do that, and I honestly said yes.

Then in 1948 I gave birth to a son and we named him Adomas. It was the name of the secretary of the Komsomol organization of the partisan squad, Alexander’s friend, who had perished with him. It was the period of time when maternal leave was given only for two months. So, I went to work as soon as the leave was over. My mother-in-law helped me raise the children. In the post-war period she retired. My mother helped me a lot as well. She lived with Dora, but called on me almost every day.

It was the period of state anti-Semitism, which was spread from Moscow to the outskirts like a multi-headed sea serpent. The struggle against rootless cosmopolites [see Campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’] 18 was in full swing. The papers were full of articles about doctors being murderers [see Doctors’ Plot] 19. My husband and I understood that we could become victims as well. That was the way it happened.

In 1951, my husband was demobilized from the army without any explanations. He remained jobless. He felt dejected. I tried to support him the best way I could. After some weeks I was fired as well. The true hypocrisy of the Soviet regime was shown now. They didn’t want to dismiss me completely as I was very literate, and had an excellent command of Lithuanian, Russian and even foreign languages. They couldn’t leave me in the administration of the Central Committee of the Party because anti-Semitism was thriving. In one of the publishing offices of the party, they introduced a new position with a personal salary especially for me, and I was employed there. All those events affected the nerve system and health in general. My father-in-law, Jacob Yatsovskiy, was stricken with an illness, having been worried about anti-Semitic campaigns and the troubles of his children. He stayed in bed for a couple of weeks and died in 1952. He was buried in the town cemetery in Vilnius.

Stalin died in 1953, and my father-in-law had passed away by that time. I don’t think he would have cried or mourned like many others. Both he and Maria practically disbelieved the ideals which they had devoted part of their lives to. At any rate, my mother-in-law took the death of our leader more or less calmly, even ironically. I cried and suffered sincerely. Maria and Evsey gladly took the resolutions of the Twentieth Party Congress 20 and divulgement of Stalin’s cult. It was more obvious for them than it was for me. After Stalin’s death I was hired by the administration of the Central Committee as the chief accountant. Evsey also got an excellent offer. In the post-war years he entered the Moscow Juridical Institute, which had the extramural department in Vilnius and graduated from it with honors. Evsey was offered a job at the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Lithuania. He worked there for many years and became the head of one of the departments. Evsey was joking that before the war he couldn’t have imagined himself anything but an artist, but he became a lawyer which didn’t seem to be fit for his nature.

We had a happy living. I loved my husband very much and he cared for me, too. Both of us doted on our children. My husband treated my relatives really well, too. I was always close to my mother and sisters. My mother got ill rather often after the war. She tried to observe Jewish rites while she was breathing. She went to the synagogue and ordered a Kaddish for my father. My mother always tried to observe the kashrut and didn’t work on Sabbath. She fasted on Yom Kippur and marked Pesach. She always had matzah for that holiday and we, children and grandchildren, went over for dinner on the first day of Pesach. In 1957 my mother died. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery and an elderly Jew recited the Kaddish for her.

My mother didn’t live to see her third grandchild. In 1959 I gave birth to a boy. He was called Jakuba, after Jacob Yatsovskiy. My mother had passed away, so my mother-in-law helped me raise my boy. Maria and I bonded well. She didn’t have a daughter, but she considered me to be her daughter. I loved and respected her as well. Maria died in 1972. She was buried in the town cemetery, the way she wished. After all, she was an atheist.

All those years I was keeping in touch with my sisters. The eldest, Dora, worked at a secondary school as a mathematics teacher. Then she retired. Dora died in 1985. Her daughter Elena got higher education. She lives in America with her family. Riva couldn’t forget her husband, who perished, for a long time. She was often proposed to, as Rivasya was a beauty. She couldn’t make up her mind to get married. Finally, she agreed, but it wasn’t the best choice. Her husband, a Jew, Shtrenene, didn’t act the way a Jew was supposed to. He liked liquor and got drunk, and then he became harsh and aggressive. Riva moved with him to Klaipeda. There she gave birth to twins: a boy and girl. Riva died early, in the mid-1970s. She was afflicted with jaundice. She was taken to the hospital and passed away there. When she died, her husband took the children away, and we didn’t get in touch after that. I don’t remember the names of Riva’s children. I only saw them two or three times in my life. My third sister, Malka, and her husband left for Israel in the late 1970s. Shleime died a couple of years ago and Malka lives by herself now. They didn’t have any children.

My husband and I were happy together, raised children. We had an average living wage. Our salaries were a little bit higher than average, and it was impossible to make more. We had enough for a living, but we had neither a car nor a dacha 21. Though, once my husband bought a ‘crate’ and he spent more time under the car, repairing it, than in the car. We always went to the best resorts in the country, getting trip vouchers from our organizations. We went to Palang, the Crimea and Caucasus. Sometimes we took the children with us, but mostly they went to pioneer camps. We also were avid readers. We didn’t miss a single cultural event in Vilnius: we attended all theater performances and concerts. We nurtured love for beautiful things in our children.

Our children embodied the dreams of their father. We, parents, were so happy to see what we could have never expected. All our children had artistic talents like my husband. Alexandra, Adomas and Jakuba graduated from the Vilnius Institute of Arts. They are specialized in different fields. Alexandrа deals with theater decorations. Adomas is a theater artist. He has worked in the Vilnius drama theater for many years. Now he is teaching at the Academy of Arts. He works with many producers, often goes on trips overseas. Jakuba became an expert in computer graphics. He is considered to be one of the best experts in Lithuania.

Jewish traditions weren’t observed in our family and the children weren’t nurtured in them. On Pesach I went to Dora’s or Malka’s sometimes. We just commemorated our parents. We paid close attention to things happening in Israel, sympathized with our national brothers during the Six-Day-War 22, and other conflicts. Our family didn’t think of leaving the country. Our children were raised as internationals. All of them are Jews, but the epoch they were raised in, made certain adjustments. They never observed Jewish traditions, though they respected them as much as the traditions of other people.

All my children decided to marry non-Jews. Alexandra’s private life wasn’t easy. She married a Lithuanian, Jurovichkas, and gave birth to two children, one after the other. She has a son, Lukas, who was born in 1975, and a daughter, Maria, born in 1976. She was named after her grandmother Maria. Unfortunately, Alexandra’s family severed in 1979: her husband took to the bottle. My husband and I helped Alexandra a lot. She wouldn’t have made it without us, neither from the moral, nor the material standpoint. We have always livеd together. Now, in 2005, Maria, my favorite, is finishing the Academy of Arts having followed in the footsteps of her mother. She is to take training abroad. Lukas wasn’t willing to get higher education. Now he is a manager in some firm. Adomas got married too early, in my opinion. It wasn’t in my principle to object to the choices of my children. His wife Laima is a Lithuanian. She teaches English. Adomas has a son, Marius, named in honor of his grandmother. Jakuba’s wife is also Lithuanian. They have a son, Justas.

My husband worked in the Presidium of the Supreme Council for about 20 years. Then he went to work for the Supreme Court of Lithuania. At that period he took a keen interest in Lithuanian and Jewish history. He defended his dissertation on history [see Soviet/Russian doctorate degrees] 23. He wrote five books on the history of Lithuania. When our republic gained independence [see Reestablishment of the Lithuanian Republic] 24, and the opportunity of revival of new Jewish culture, my husband was one of the first who took the initiative to start the Jewish community. He was there when the United Jewish Community of Lithuania was founded. Unfortunately, he didn’t have the chance to work for a long time. In 1994 Evsey died.

Since that time I have lived in the house with my daughter and her children. Adomas and Jakuba have their own apartments. My daughter and I are real friends. Neither of us interferes in somebody else’s life. We have our own interests and respect each other. In spite of my elderly age, I feel myself as totally independent. It’s my main trait. I have worked for the Jewish community as an accountant for quite a few years. I’m among the people who have the same values. I’m happy. There is an opportunity of national revival in the independent Lithuania, and I deem it to be the most important achievement. Now I mark Jewish holidays with pleasure and my children with their families come over to my place on Pesach, Chanukkah, and Rosh Hashanah. I fast on Yom Kippur, often cook Jewish dishes like my mother did, and teach my daughter and granddaughter how to cook. As Alexandrа says, ‘Better late, than never!’

Glossary: