Jacob Mikhailov is a tall and lean, grey-haired man with bright blue eyes and with a crew-cut framing bald head. Jacob is very sociable and hilarious. He enjoys joking and laughing. He was willing to share a lot about his life, and the life of his family with me. He lives with his wife Elena in a two-room apartment in a building constructed in the 1970s in the city of Moscow. Elena takes credit for an impeccably clean and cozy apartment. There are a lot of books in the apartment. Jacob and Elena are avid readers. They like to share opinions of the books they read. Every day their only grandchild Artyom, the most important family member, comes to see them. Jacob loves his grandson very much and pays a lot of attention to him.

My family background

I know little about my father's family. I never met my paternal kin. My father didn't talk much about them either. My father, Mark Vengrovich [he later changed his surname to Mikhailov because of communist ideology], was born in 1897 in Warsaw. It was the territory of the [tsarist] Russian empire at that time. As father told me grandfather was a merchant of Guild I 1, a very wealthy man. They lived in the center of Warsaw. I also know that my father had a younger brother named Genrich. When my father left home, Genrich was in his junior year at a lyceum. When I was in my teens I remember that my father got a message from Genrich saying, 'Still alive and kicking.' That's it. No news came from Genrich after this time.

Father went to trade school in Warsaw, but didn't finish it. My father was fond of communist ideas, and he left home when he was 16. He stopped being in touch with his family then. He went to Russia, and never came back to Warsaw. I practically don't know anything about my father's prenuptial life. Father adhered to revolutionary ideas, and then became a member of the Communist Party. The party was banned, so its members took alias known to other party comrades. My father's party alias was Mikhailov. Then his surname was changed to Mikhailov as well. This name was written in the documents. In February 1917, when the Provisional Government 2 was in power, my father was imprisoned for revolutionary activity [during the Russian Revolution of 1917] 3. Before getting married my father lived in Kharkov [in today's Ukraine, 440 km from Kiev]. I don't know how he happened to get to Kharkov from Moscow.

My mother's family lived in Chernigov [180 km from Kiev], a beautiful ancient city in north-western Ukraine. Chernigov seemed small to me. It's difficult for me to describe how I perceived the city in my childhood. I used to stay with my grandparents for the whole summer. I went to the forest with other children. We also went to the rivers, played in my grandmother's house. I didn't see that much of the city. I remember the greenery of the city. I was six the last time I was in Chernigov, before the war. I'm certain there was a Jewish cemetery in Chernigov, which is still there. There might have been several synagogues. But I wasn't interested in that in my childhood. As an adult I went to Chernigov with my daughter, and it was a totally different city: modern, with multi-storied buildings, not looking the way it did in my childhood. [Editor's note: in Chernigov the Jewish population numbered more than 14,000 in the 1910s and app. 10,000 in 1926 (30 percent of the total population). The last synagogue was closed down by the authorities in 1959. In 1970 the Jewish population of Chernigov was estimated at 4,000.]

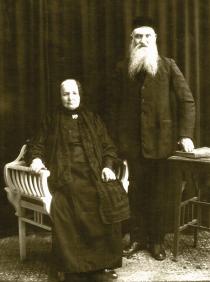

My maternal grandfather, Abram Nitsberg, was born in Chernigov in the 1850s. Grandmother Sophia Nitsberg was also born in Chernigov. I don't know exactly when she was born nor do I know her maiden name. All I know is that she was ten years younger than my grandfather. Grandmother's Jewish name was Sarah. But the grandchildren called her Sonya. Grandfather was a stubby man of medium height. He had a long beard. He wore a black silken kippah on his head. Grandmother was short and buxom. She wore traditional Jewish clothes: long black skirts and dark long-sleeved blouses. She wore a black kerchief on her head, and during solemn occasions she wore a black lace shawl. Grandmother was very kind; her eyes radiated kindness. Probably all grannies are kind, but mine seemed to be the kindest.

Grandfather worked in a sort of work association. He sold fish. I don't know what his job was like; all I know is that he didn't own the business. Grandmother was a housewife. My grandparents had a cow. They also had a kitchen garden and planted vegetables there to feed the family. They lived well and didn't starve. Grandmother contrived to feed her many children. I knew all my mother's brothers and sisters, but two. I know when my mother and her eldest brother were born. The difference in years between the brothers and sisters wasn't big - approximately two years. My mother's eldest brother, Noy Nitsberg, was born in 1879. I don't know the second's brother name. The third brother's name was Jacob. Then Solomon and Naum were born. In 1899 my mother Maria whose Jewish name was Miriam was born. Then Mikhail and Revekka followed. The youngest one, Revekka, was born in 1906, when grandmother was about 50. Grandmother was ashamed of her belated motherhood, and sometimes used to say that Revekka was her granddaughter, one of her son's daughters. Her sons were married at that time and had their own children.

I don't know for sure, but I think my maternal grandparents must have been religious. It couldn't have been otherwise at that time. Grandfather paid a lot of attention to the secular education of his children. My mother finished a full course at Chernigov lyceum, and I think she wasn't the only one who got educated in the lyceum. All children knew Yiddish, which was their mother tongue, but they also were proficient in Russian and spoke foreign languages. The children didn't get primary Jewish education.

Noy, my mother's eldest brother, was a pharmacist. He had his own pharmacy in Chernigov before the revolution of 1917. Then it was nationalized and he worked as a pharmacist in the state apothecary. He was married, and his only daughter moved to Moscow after the revolution. When he grew old and sick, his daughter took him to her place. He died in 1949 in Moscow.

My mother's second brother left for the USA in 1905. My mother told me that he married an American woman there, who gave birth to two children. They must have stopped writing to each other after the revolution of 1917 as the new regime disapproved of having relatives abroad, moreover corresponding with them. [It was dangerous to keep in touch with relatives abroad] 4 My uncle was an artist. I think his children became musicians, at least one of them. My mother told me that her brother was a good artist, who painted a lot of pictures. When he was asked to sell a picture, he said it wasn't for sale. He made the paintings for himself. He didn't sell any of his pictures. I don't know what he lived on in America.

I never met my mother's third brother, Jacob either. I was named after him, and know about him from my mother. Jacob was very gifted in anything he tried to do. Adolescent Jacob was drafted into the army during World War I. He was captured by the Austrians. His captivity probably wasn't so bad since he even managed to send his picture from there. When he came back from captivity, Jacob became a revolutionary. He took part in the revolution, then in the Civil War 5. Before being drafted Jacob was in love with a girl from Chernigov. Jacob exerted his every effort for the revolution. In 1918 the Soviet regime assigned Jacob Nitsberg the first party secretary in Chernigov. He perished accidentally in 1919. It was found out that White Guards 6 were planning to blast the bridge across the Dnepr. Jacob was to divulge that plot. One of the plotters - Jacob's lyceum comrade, a White Guard - shot at Jacob and killed him. When he was arrested he said, 'I couldn't have acted otherwise. Even if I hadn't killed Jacob, I would have been killed as a White Guard.'

One of the streets in Chernigov was named after Jacob Nitsberg. In 1950 it was renamed, it seems after Kirov, but I don't know the present name of this street. Probably the municipal authorities thought it to be indecent for the streets to be given Jewish names. When I grew up, I decided to find Jacob's grave no matter what. When my daughter left school, we went to Chernigov and found out from the old residents where Jacob was buried. We walked along the Jewish cemetery and found his grave and the tomb. It should still be there now.

Uncle Solomon lived in Chernigov and worked with the Ispolkom 7. Solomon's wife was named Basya. They had three daughters. I remember my mother's next brother, Naum, the way he looked and the way he talked. He was an officer, but I don't know where he served. He lived in Chernigov. He had two daughters and a son.

I knew the youngest siblings, Mikhail and Revekka very well. Mikhail worked with the NKVD 8 for many years. He left the organization before the war and began working for a construction company. Galina, Mikhail's wife was from Leningrad. She had two children, a daughter and a son. They lived in Kharkov before 1936 and when Kiev became the capital of Ukraine they moved to Kiev. [Editor's note: before 1934 Kharkov was the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, in 1934 the Government of the USSR decided to move the capital to Kiev. All governmental structures moved to Kiev as well]. During the Great Patriotic War 9 Mikhail was drafted into the army, and his family was evacuated to Central Asia. During the defense of Kiev, Mikhail happened to be in the siege, and when he broke through he went to the partisans' squad. He perished there, and the circumstances remain unrevealed. When Galina and her children came back from evacuation to Kiev and got to know the news about Mikhail, she moved back to her hometown, Leningrad. Their children still live there.

The youngest in the family, Revekka, lived with her family in Kharkov. Her husband, Pavel Lev, was the closest relative to me. He treated me very well and we bonded. Revekka and Pavel had an only daughter, who was very feeble. Revekka was a housewife, paying utmost attention to her daughter and husband. The daughter died before the war. When the Great Patriotic War was unleashed Pavel went to the front. Revekka was evacuated. Pavel went through the war and stayed in the army for a while. Revekka stayed with us in Moscow at that time. When Pavel came back from the army, we tried to talk them into staying in Moscow with us, but Pavel was longing to get back to Kharkov. In the end, he left. Revekka died in Kharkov in 1976. Pavel didn't live long afterwards. I cared for Revekka and Pavel very much. I used to visit them almost every year. Then I came to their funeral, which was secular. They were buried in a city cemetery. The last time I was in Kharkov four years ago, I went to their graves.

My mother didn't tell me whether there were Jewish pogroms in Chernigov before the revolution [see Pogroms in Ukraine] 10. Their family house was located on the street where Chernigov's vice-governor lived, so it was serene and quiet there. With the outbreak of the Civil War, the whole family was to move to Sarapul [today Udmurtia, Russia, about 1,800 km from Chernigov]. At that time Chernigov was plundered by Gangs 11, Denikin 12 troops, sometimes Jews were killed. My mother caught typhus fever in Sarapul; it was hard for her to convalesce. Then, the family returned to Chernigov. Mother finished the lyceum with distinction, and wanted to go on with her education. She left for Kharkov and entered the Medical Institute. Father studied at the Institute of State Economy; he graduated from it in 1924.

My parents met in Kharkov. I don't know the details of how they met. They got married in 1921. Of course, it wasn't a traditional Jewish wedding as they were convinced communists. I think they didn't have any wedding, just a mere registration. My mother was in her second year, when I was born. My mother went to her parents in Chernigov before delivery, and spent a couple of months there after parturition. I was born in Chernigov on 19th June 1925. My mother had to quit her studies after she returned to Kharkov.

Growing up

Even though our family stayed in Kharkov only until 1930, I remember our house very well. It was a U-shaped five-storied brick house with a front yard. It seemed huge to me at that time. The house is still there. There was the Kharkov Opera Theater next to our house. We could hear the opera performances as if we were in the hall. Then, the opera theatre was moved to another building, and was taken over by the Russian drama theater. We lived on the fifth floor of the communal apartment 13. There was a common kitchen, toilet and bathroom. There was centralized gas, sewage and running water. We had two rooms. There were five more families in our apartment. I don't remember all of them. I recall a woman, who lived next door. Her name was Marusya, she was Russian. Her daughter was my coeval. There was also a Jew, Hanna, who worked with the NKVD.

One room was taken by my parents, the other room was mine. I don't remember how the rooms were furnished. I can only recall my father's oaken desk, which has been kept until now, and the bookshelves with the books. There weren't a lot of books. That was mostly father's specialist literature. Father worked in the chemical industry. He wasn't an ordinary worker.

My parents spoke only Russian at home. If they wanted to conceal something from me, they would exchange a couple of Yiddish phrases at times. I wasn't very good at Yiddish. Father also spoke good Polish. Our neighbor was a Pole, and my father was always happy to communicate with her in her mother tongue.

I spent the whole summer in Chernigov with my grandmother. All grandchildren were brought together. Mother's sister Revekka also used to come there with her husband and daughter to spend the summer. They were happy times. Grandmother cooked. Pavel and Revekka played with the children. We went for strolls to the forest, the beach, and performed puppet shows. The elder read fairy-tales to the younger ones. Sometimes my uncle took all boys angling. We left at dawn, and came back for breakfast. All grown-ups spoke Russian with the children. The house was spacious and there was enough room for everybody. It was a two-storied brick house with a basement. Mother's brother Solomon was the host. His family was on the first floor, grandmother took the second floor. The basement was taken by tenants. There was a fountain in the yard in front of the house. It was probably the only fountain in Chernigov at that time. There was a beautiful orchard behind the house. There was a variety of fruits there.

When I was in Chernigov with my daughter looking for Jacob's grave, I was shown the street where my grandfather had lived. Strange as it may be, I found grandfather's house surrounded by new multi-storied buildings. I entered the yard and recollected everything: the place where pen and coop were, the summer kitchen etc. The orchard had turned into a jungle, teeming with weeds. It was fall, and there were big piles of apples and pears under the trees. I wanted to get in and ask the new hosts to see the place that had been dear to me since childhood, but nobody was in. I picked up an apple and enjoyed its familiar fragrance.

There are certain scraps of my childhood in my memory. I remember my grandmother to cook cherry jam in a huge copper basin. I reached to pick a cherry and scalded my arm heavily. I was taken to the doctor and I remember how he praised me for not making a sound during the treatment of the wound and bandaging. I remember how Grandfather used to send me to the bakery for challah, and I removed the crunchy crust and ate it on the way home. Maybe grandfather got so mad because the challah was meant for Sabbath. I don't remember my grandparents to celebrate Sabbath at home; frankly speaking, I preferred to spend time with my cousins rather than with the adults. Once, my grandfather gave me a pocket watch. I was keen to know why the hands were moving, so I dismantled the watch into tiny pieces. Grandfather scolded me, but my grandmother stood up for me. She picked up all the parts and took them to the watchmaker, and they were put together again. Grandmother forgave her grandchildren entirely no matter what we did. We were very rarely punished. I remember how I lolled out my tongue in front of my grandmother. Late at night, after Uncle Solomon came back from work, he flogged me for lolling out my tongue. Such little incidents were not in the way for my love for my relatives. I always kept in touch, called and sometimes came for a visit.

Once, my grandparents came to Kharkov to see us. They spent a week and left. All of us talked them into staying longer, but grandmother didn't want to leave her household for a long time. I was six, when I visited my grandparents for the last time. I came to them from Moscow before schooling.

In 1929 my father was transferred to the Ministry of Chemical Industry in Moscow. My father left by himself. My mother and I followed him after he had been given the apartment in Moscow. The apartment was located on Krasnoprudnaya Street. We had a two-room apartment with all modern conveniences. It was a separate apartment, which was a rare thing back in those times. Most of the people continued living in communal apartments. My father's apartment was on the 3rd floor, but we changed it for the 5th floor as one of the residents asked for it because it was hard for him to climb the stairs. My father wasn't against it. He thought he wasn't entitled for a better living than others. Later, in 1935 my father was offered a four-room apartment in the center of Moscow, on Ananyevskiy Lane. Father tried to persuade mother's brother Mikhail to move to Moscow. Mikhail didn't want to move, so Father turned down the apartment saying that there was no use in such a big apartment for us.

When we moved to Moscow, my mother started working. She worked for some company for a while, and then she was offered the position of an economist in the planning department of the Ministry of Foreign Trade. Mother worked there until her retirement. She was loved and respected. No matter that my mother was offered to join the party for a number of occasions, she refused it saying that she was apolitical. We were well- off. My pre-war childhood and adolescence were the best period of my life.

I was closer to my mother than to my father. She was an open-hearted and benevolent person. I always felt her love. Father was different. He also was very decent and honest, but he was constantly busy and he couldn't find time for me. Mother also was very busy. Before the war, I saw my parents once a week, on Sunday. They went to work two hours after I left for school. When I left, they were asleep. When they came back, I was asleep. Nevertheless, I think my parents taught me a lot, and influenced my mettle. One could interminably reiterate that you should be decent, honest and fair, but without setting one's own example all that nurturing would be futile. My parents should be given credit for all good things I have as they taught me with their good example to follow.

Of course I wasn't on my own. From the time I left for Moscow in 1939 I had a nanny. Her name was Vera. She came from a village in either Poltava or Chernigov oblast. She wasn't just a nanny, she was also a housekeeper. She was a very close person to us, a member of our family. She went to see her kin, caught a cold and died. My parents went to her funeral. It was hard for us to get over Vera's death. We commemorated her for a long time. My parents were never arrogant towards people inferior to them. My father had a car with a personal driver, and there wasn't a single time that the driver wouldn't eat with us if we were having a meal. We knew everything about our family, and he knew about our things in the house. My parents taught me to treat people this way.

In 1935 my grandmother was afflicted with pneumonia and passed away. She was about 75. Then my brother Solomon died after her. Grandmother and Solomon were buried in the Jewish cemetery in Chernigov. After Grandmother's death, my grandfather stayed with Solomon's family. Basya, Solomon's wife took care of him. In 1939, my grandfather had a cervical hip fracture. He was quite senile, aged about 90. The fracture was very complicated, and there was no hope that the bones would knit together. Grandfather was bedridden for a year. Basya and three of her daughters looked after him. In 1940 my grandfather passed away. He was buried next to Grandmother. I cannot tell for sure, but I think the funeral wasn't in accordance with the Jewish rites, as my grandparents were atheists.

In 1932 I entered pre-school. At the age of seven I went to a pre- school class. At that time pupils were only accepted to the first grade of secondary school from the age of eight, but at schools there were classes of preschool preparation. We were taught the alphabet and rudimentary figures and other things to get ready for the first grade. I cannot say that I was a good student. I was very fidgety and was often summoned to the principal's office with other boys. We were not hooligans, but often frolicking. None of the school subjects were my favorites. Though, there was a time in the fifth or the six grade when my friend and I went to the literary circle held by our literature teacher. But I reckoned on that: we could have poor marks during lessons, and then both of us could compose some poem and would be given good marks for the quarter. I was mostly attracted to football during school time. I'm still keen on it. I was in the fifth grade when I appeared in the stadium for the first time, and I have been fond of football since then. I tried not to miss the matches of my favorite football teams. Now, I am not that big of a fan any more. I think nowadays football is a travesty. Back in those times people played for the sake of the game and love of football, deriving pleasure from scoring a goal. Now money is the pivot.

I was in the first grade when I was accepted to the Octiabriata [Young Octobrist] 14, then I became a pioneer [see All-Union pioneer organization] 15. I wasn't a Komsomol 16 member in school, though. When the Great Patriotic War was unleashed I finished the eighth grade, and I was not eligible for the Komsomol yet.

There were a few Jewish children in my class. We didn't feel any difference between Jews and non-Jews. Both teachers and classmates had the same attitude towards different nationalities. Anyway, I never came across any collisions.

Mother wanted me to know a foreign language. A German lady who had stayed in Russia for a long time, taught me German. Our classes lasted for several years and I was pretty good at German. By the way, as soon as the war started, she was fired and nobody knew what happened to her next. She was most likely unhappy.

In 1933 Hitler came to power in Germany. I was too little to be interested in that. I was politically aware after I became a pioneer. Pioneers were interested in the events in Germany, discussed at our meetings, and condemned fascism. Anti-fascist movies such as 'Professor Mamlock' 17 were shown in the cinemas. We saw this movie for several times, read the articles about the atrocities of the fascists. Of course, we thought fascism to be a crime.

We had a clear understanding of what fascism was when the war in Spain [Spanish Civil War] 18 was unleashed. It goes without saying, that all of us were on the Republicans' side. War chronicles were shown in the movie theaters at that time. Spanish orphans, whose parents were killed in the war, were brought from Spain. We desperately envied adults who were able to be volunteers at war. An adopted Spanish boy of my age lived in our house. I made friends with him. We remained friends as adults. All of us hated fascism and detested Hitler. I don't know how it was with the grown-ups, but we, the children, couldn't comprehend how a peace treaty, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact 19, could possibly be concluded with Hitler. I remember the arrival of Ribbentrop in Moscow. My mother said surprisingly that his face was pleasant.

In 1936 arrests commenced [during the Great Terror] 20. My father was deputy head of the leading committee and he testified to that. He used to get back from work and tell us about new appointments of other people to leading positions. I knew that it meant the former leaders' imprisonment. I don't know what my father was thinking at that moment; maybe he was hoping that it wouldn't touch him. There was a time when my father worked with Polina Zhemchuzhina, Molotov's 21 wife. Once I used to come to my father's work and heard him talking to Zhemchuzhina. My father introduced me to her. She patted me on my shoulder and gave me two big oranges.

I was shocked by the arrests of enemies of the people 22, such eminent militaries as Yakir 23 and others. They were idols for us, the boys. My mother had known the family of Turovskiy, deputy commander of Kharkov, since childhood. They were born in Chernigov, and Turovskiy lived there for a while. Once my mother took me to the cinema to see a documentary on military maneuvers, and Turovskiy was in that movie. Then, after a while, he turned out to be an enemy of the people. I couldn't believe the things published in the press, and I couldn't comprehend how it could have occurred. It didn't make any sense to me. I tried to talk to my father regarding that. He also used to say, 'I cannot understand how people who went through exile, civil war and prisons all of a sudden turn out to be the enemies.'

We had such talks; neither my friends nor I ever took it personally. Some of my schoolmates' parents were 'enemies of the people.' They kept on studying at school, and their teachers treated them the same way they had before, without making them reject their parents and condemn them. Only later I understood that it was the teachers' merit. [Editor's note: in the USSR it was characteristic for teachers to be ideological workers, and their job was to identify and besmirch the children of enemies of the people, making them publicly reject their parents, who were unwanted by the regime. If it didn't happen in this case it was the teachers' merit.]

During the war

In 1939 Hitler attacked Poland and our troops were mobilized there [see Invasion of Poland] 24. My aunt's husband Pavel was drafted into the army and dispatched to Poland. Fortunately he had been demobilized before the Finnish campaign started [see Soviet-Finnish War] 25. I remember my uncle's tales about the war in Poland. During the Polish war and the 'liberation' of Western Ukraine there weren't even enough rifles for all the soldiers. There was one rifle for several people. There were no battles though. Our army had to be more careful with the Polish than with the Germans, who came to a certain point and stopped. The part of Poland where our troops came was very antagonistic against our army and they were vindictive towards the Polish division. There were cases when a Soviet soldier came to the barbers for shaving and was killed with a razor blade.

We were brought up with propaganda. We were raised with movies as 'Esli Zavtra Voyna' [If War Comes Tomorrow, USSR 1938] and such like. We were convinced if somebody dared to attack our country, he would be defeated and there would be little blood-shed on foreign territory. Frankly speaking, I wouldn't have imagined that such a powerful state could be attacked. I couldn't even think that Germany would attack the USSR after the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact had been signed. Of course, such propaganda was a mere profanation and duping, but only later on I came to understand that.

On Sunday, 22nd June 1941 our family was about to move to a dacha 26. But in the morning my father was given a call and told that the driver had lingered on and should postpone moving until next week. I was happy to hear that as my friends were going to Sokolniki stadium to play football. I joined them. When we got to Sokolniki we saw a throng of people clustered by the loud-speaker. We stopped and were told that a paramount important message from the government was about to be announced. We listened to Molotov's speech, who said that treacherous Germany had attacked the USSR. We went back home. All day long we were discussing when our troops would be crossing the border. People outside had likewise talks. The next day we would ask each other with hope whether our troops had crossed the border. There was no information on the radio for a while, only optimistic promises that the enemy wouldn't cross our territory. Only a few days later we found out that Minsk had been captured by the Germans. They didn't even say a thing about the battles with the enemy on this territory. Then, when the Germans were deep in the country, for thousands of kilometers, there was nothing to say, but, 'After severe fighting our soldiers had to retreat from such and such city ...'

At the beginning of 1941 father was transferred to the Ministry of Coal Industry, which was evacuated to Molotov [today Perm, 1,250 km from Moscow] in June 1941. Moscow wasn't bombed at that time. Bombing started in August. Mother left her job, and the three of us were evacuated. We traveled in a crammed freight car for five days. There was provision in Moscow shops still, so we took some food with us. It was possible to buy things at the stations. We were lodged in a private house in Molotov. The hosts gave us a six-square meter room for the three of us. First there was some food in Molotov, and we ate at a canteen. About a month later the food cards [see Card system] 27 were implemented.

Then mother's sister Revekka came back from Kharkov. She was first evacuated to Novosibirsk [about 3,000 km from Moscow] and stayed with her husband's brother. Her husband Pavel was at the front. Revekka stayed with us for a while and then left for Novosibirsk. I went to the ninth grade of the local school. Mother worked in some office. In half a year my father was called to Moscow. My mother and I stayed in Molotov until July. Mother wanted me to finish the ninth grade. There were battles for Moscow and we were constantly listening in round-ups. I didn't even admit a thought that the Germans might take Moscow. I was sure that our army wouldn't give up Moscow, and it happened so. We lived from one round-up of the Soviet information bureau to another.

When my father came back to Moscow, there were some people in our apartment. In a year by court ruling our apartment was given back to us, and in July 1942 my mother and I came back home. The director first didn't want to let my mother go home. He gave in after receiving a governmental telegram signed by the deputy minister of foreign trade with the request to let my mother go to work in Moscow. Mother regained her work in the Ministry of Foreign Trade. I went to the tenth grade in September. I wanted to go to the army as a volunteer that is why I had an independent tenth-grade course for two months and passed my exams pre-term. In November 1942 I was issued a certificate of ten-year compulsory education.

Our life in Moscow during war times considerably differed from the pre- war period. Mass air raids stopped, and bombing was occasional. The Germans were thrown out of Moscow. There were air-raid shelters in Moscow, but some people were used to bombings and didn't leave their apartments during bombing. Many houses were demolished during the siege of Moscow, but our district wasn't devastated at all. Of course, we were hungry, but we managed somehow. It was more difficult to get over the cold. Central heating was turned off and the winter was severe. One room was locked, and the other was heated by a self-made stove. It was heated with anything we could possibly find: furniture, boards and branches I was looking for on the streets and in the parks.

In December 1942 I was drafted into the army. I hadn't reached the drafting age of 18; I was 17 at that time. We were brought together by groups in the military office. My group was sent to Yaroslavl [about 200 km from Moscow] to the gun school. I was sent back home as they told me there that I wouldn't go through the examination commission. I celebrated the New Year of 1943 at home in Moscow. I was summoned to the military enlistment office a couple of months later and was sent to the military engineering school near Moscow. I was told by the physical evaluation board that I was fit for the troop duty, but not for the military school. The doctor asked what school I was supposed to enter and I told him military engineering. The doctor must have thought that it was some kind of a technical school and came to the conclusion that I was healthy.

I recall the time spent in the military school as a nightmare. We were trained even harder than in any other military schools. As a matter of fact, the training looked more like a teasing. There were two platoons. The first consisted of males with unfinished higher education, and the second platoon was comprised of boys with secondary education. I was in the second platoon. Calling our commanders martinets would be an understatement. Platoon commander Glukhov, the former front-line soldier, having been awarded, was a malicious person, though straightforward and not mean. Our division commander, who had earlier been involved in prosecution, was a real sadist. If the attendee was given extra duty for misdemeanor, he didn't give him work, he was waiting for everybody to fall asleep, and then woke up the penalized lad giving him an assignment to clean floors or toilets. What he enjoyed the most was to wake up the entire platoon at night, tell everybody to align outside and make them running to the assault course. There was no need in that; he just had fun teasing us. We couldn't stand up for ourselves. Then, approximately one year before our leaving to the front they were scared the reckoning was coming for our teasing. But they were removed three month in advance. We didn't even know the reason for their dismissal. They were taken over by the school leavers. I was in the school for a year and two months. It was a large training period considering war time. As we were to become combat engineers we were trained very thoroughly. The commander used to say that the sapper would make a mistake only once and we were taught not to make any errors.

I was given the rank of a junior lieutenant after I finished school. I was sent to the 1st Ukrainian front. Shortly after my arrival I was sent to the combat engineering squad and assigned the commander of the combat engineers' platoon. The previous commander was in hospital, and I stood in for him. In couple of months I got a higher rank - lieutenant. Then the previous commander came back from hospital, and I was transferred to the 5th paratroopers' regiment of the 2nd guard airborne division. I was there until my first wound.

Combat engineers were responsible for mine planting and mine clearance. I was supposed to join the reconnoiters, as the intelligence didn't head out anywhere without a combat engineer because the fields were planted with mines. The combat engineer was to go first and set up the route in the mine field for the reconnoiters and others. When tanks were to attack, combat engineers were supposed to check the route for them. Of course, we didn't have time to clear the whole mine field. Combat engineers moved in front of the tanks, cleared mines, and then the tanks followed the combat engineers.

Mines were buried, but they could be seen. Of course the tankers couldn't see them as the distance was too big. Sometimes they had a hunch where the mine was, even though they didn't see the mine. Anti- personnel conventional mines could be condoned as they wouldn't destroy tanks, while antitank mines would blast a tank that is why it was mandatory to clear those types of mines. [Editor's note: Originally developed in World War II, the PMD-6 antipersonnel mine is a rudimentary pressure-activated blast device in a wooden box. As wood rots, the mine mechanism may shift, and the device often sets itself off or becomes inoperative.]

Our task was also to maintain a caution crossing. There were special well-equipped squads with bateaus for this mission. But we lacked such squads and caution crossing was provided by ordinary combat engineering troops with expedient means. Once we had to ford across the river Latoritsa in Western Ukraine. Our squad approached the river. We couldn't approach the bank as the Germans launched a severe gun attack. The regiment commander gave an order to ford the river at night under the cover of darkness. I remembered what we were taught in school. We got long boards and bound them together with rope and wire and then brought them to the river in carts as soon as it got dark. We had a raft with the length of 70-80 meters. We also prepared long six-meter rods to push off from the bottom. I and five more people got on the raft and tried to veer it across the river with the help of the rod. But the rods were too short and didn't reach the bottom. The river wasn't very wide, about 50 meters, but it was deep, deeper than eight meters. The river stream pulled the raft along, and we had to pull against. We were lucky that the wind direction didn't allow the Germans to hear the splashes coming from us.

My watch showed 4am. The dawn was before soon, and the Germans would just shoot us down. I saw the commander on the bank waving his hands and making signs to veer the raft. What were we to do? It was December and our raft was getting covered with ice. Surprisingly enough I didn't even think about the fact that I didn't know how to swim. One slip and I would be in the water sinking like a stone. We couldn't reach the bottom with the rods. The only way out was to swim to the bank and get the rope tied to the raft. One of the soldiers undressed and swam in the freezing cold December water. He swam for two meters and had a cramp. Another soldier followed him. We tied him up with the rope for him to get on the raft if he had to. We were lucky. The soldier reached the bank. As soon as they hauled on the rope from the bank, the raft was veered across the river and the entire squadron crossed the river, landed at the other bank and succeeded in attacking the Germans.

I was lucky not be wounded at war no matter that I was in the skirmishes. I really considered myself a fortune minion, who couldn't possibly be wounded. I don't know why but I was convinced of that. The first time I was wounded was in Hungary in 1944. We came to a hamlet after receiving the message from the headquarters that it was occupied by our troops. I went halfway on the tank turret, and then I got off to check whether there were any mines getting a hold of the tank weapon. Then all of a sudden shooting was coming from that hamlet. It turned out that it was occupied by Germans. The tanks turned around and retreated; I was close to the tanks. But I couldn't move forward way too far as a mine fragment hit my head. I was unconscious for a while. When I came around I saw a local Hungarian woman sitting by me. She tore a piece from her chemise and bandaged my head. I was hospitalized with that wound. Then I came to the understanding that I could be wounded, not killed.

I was sent to the 7th air-borne regiment of the 2nd guard airborne division after I was discharged from hospital. The combat engineering commander perished and I was assigned new platoon commander and stayed there until the end of the war.

I didn't join the Party while in the army. The political instructor used to annoy me with requests to join the Party after I had become officer and platoon commander. I declined saying that I wasn't a Komsomol member, and besides at the age of 19 wasn't eligible to be a party member. In the end I was pushed to become a Komsomol member.

It was mandatory to take any city on the eve of some Soviet holiday. It was common practice no matter that the situation wasn't auspicious for that. It should have been the time of respite, but we had the order to liberate any city at any cost. It meant thousands of casualties just for reporting to the supreme, e.g. 'Comrade Stalin, to commemorate the anniversary of the great October Socialist Revolution Kiev has been liberated.' I remember how in 1944 an article appeared in Pravda [one of the most popular communist papers in the USSR, issued from 1912 till now, with the circulation exceeding eight million copies during the Soviet period] saying that in severe battles the troops of the 4th Ukrainian front took the passenger terminal and the town of Chop [Zakarpatska, Ukraine]. Yes, Chop was taken but it couldn't be retained as the Germans put on more pressure. Then there were more casualties in attempts to liberate Chop.

I went to reconnoiter many times. Then I was involved not only in combat engineering but also in reconnoitering. I recall one case. I was sent to reconnoiter with a group of people and I was told that we should cross the front line. I wasn't told who these people were. When I came back to the squad I was told that those people were German anti- fascists who had come through the front line to their military divisions to propagate against Hitler. I thought their mission to be very hard. They could have been killed at once if not disposed to the Gestapo. Then I understood that Germans and fascists were two different things. There were Germans who fought against Hitler.

I was wounded the second time in Poland, not far from Poznan, in the direction of the river Oder. It happened in March, 1945. The altitude by the Oder was 936 as marked on the maps. First the altitude was taken by us, and then it was taken by the Germans after our retreat. There were few people and the personnel wasn't replenished no matter that our commandment was constantly asking for it. The general headquarters cabled the following: 'Finish the war with the means you've got without awaiting replenishment.' We had more equipment than men and more officers than soldiers percentage-wise. Soldiers weren't that willing to attack as they knew the war was coming to an end, and they didn't want to die. Combat engineers also tried to escape jeopardous assignment obviating the risk.

Combat engineers didn't have to assault, but we couldn't condone the orders. Gun soldiers who were to defend the headquarters were under my command. These were several combat engineers and infantry men. We reached an altitude in the evening and it was getting dark. All approaches to the altitude were lined with the corpses of our soldiers, who had made the attempt before us. But we had to act no matter what. I tried to convince the soldiers to attack. But nobody moved. Everybody wanted to live. Frankly speaking, I had to kick and shove them so they could get up. Then the words came - 'For the Motherland! For Stalin!' - and we attacked. A fragment reached an arch of my gun and the spent bullet broke my finger. Then the fragment pierced my leg. In the ardor of the battle I felt no pain. Only later I felt that I couldn't walk, and my leg pulled back. When the altitude was captured, I told the commander over the phone that the order had been fulfilled and asked for a permit to be hospitalized. Luckily the bone wasn't touched and I wasn't sent to the rear regiment. I stayed in the hospital for three weeks and then I returned to my regiment.

When we arrived in Germany, the hunt for trophies began. We could enter any devastated German house and take anything we wished. I couldn't even think of anything like that, but the older soldiers, especially the rustic ones, were seeking what might be in need. I recall that one of the elderly village guys found a 50-meter roll of silk. He wrapped himself up in that silk and walked around. I suggested that he should put that silk in the cart as nobody would take it anyway, but he didn't give in. He found his life very precious since he found that trophy. When we were having lunch, he went to the basement so as not to be killed in an accidental skirmish. Strange as it may be, he was the only one to die during a skirmish: the vault collapsed in the basement where he was hiding.

Most of us didn't hate the Germans. In battle it's different: an extermination of the vicious foes. We were calm towards captives and civilians. There were no people around who hankered for the death of the families of German soldiers. I had to participate in cross- examinations of the Germans because I spoke pretty good German. None of the captives recognized that he was a military. Some said they were barbers, others were builders; they named any profession that came to their mind. We treated captives in a good way. I remember that captured Germans slept along with our soldiers in the basement, and the weapons were close by. None of the Germans made an attempt to get a hold of a weapon. Captives were fed together with us. I saw the columns of captured Germans lead by two elderly soldiers. It was hard for one of them to carry a gun as it was heavy, so he put it on the shoulder of a captive. The Germans didn't try to escape or disarm the sentinel. They understood that the war was over, and they wanted to remain alive.

There was no anti-Semitism at the front. Nobody was interested what nationality the comrades were. There were other criteria: would your comrade give you a hand when you are in a quagmire, would he defend you from a skirmish or would he share rusk and water with you? There were Russians, Ukrainians, Georgians and Moldovans [also see Moldova] 28 among my front-line friends. There was no national feud.

For my friends and I the war was over not on 9th, but on 12th May 1945. The commandment was apprised that the German squad under the command of colonel-general Sherner was trying to break through to the Americans. Our front was to block their way. Part of our gun-machine battalion captured some hamlet, located 40 kilometers south-east of Berlin. We didn't take part in the liberation of that hamlet. Our squad, headed by the operational squad of the regiment, walked across the field and blocked the road. There were knolls ahead of us and shooting started from there. There must have been a spotter there, who spotted the fire. The shells were blasted behind us, then in front of us. I understood that we had come into a plug as they say in artillery.

There were three more soldiers with me. The shell landed right between us. I fell down after the blast. I was in a jersey and the cotton wool was erased by the shell fragment and my back was scolded. The map case was thrown away by the blast. The other three soldiers were killed. They perished on 12th May 1945. The regiment commander told me to submit a report for those killed in the last battle to be posthumously awarded and for their relatives to be apprised of that. One of those soldiers was my friend Vladimir Bishnar, a handsome good-humored Moldovan, only two years older than me. I couldn't write to his family, just couldn't stand the thought. I wanted to go to Moldova after demobilization and tell his family what a remarkable man Vladimir had been and how he had perished and my witnessing it. One thing is to write a letter, going to see them was a different thing. I didn't manage to do that. I kept my map case like the apple of my eye as it contained the addresses and pictures, and it was stolen during my trip on the train. There was nothing I regretted more in my life. That is why I couldn't meet up with Vladimir's family.

During the war I was awarded with the Order of the Red Star 29 and the Medal for Valor 30. Besides I got many medals for the defense and liberation of many cities. I was awarded with an Order of the Great Patriotic War 31, 1st Class, for my last battle on 12th May 1945.

After Khrushchev's 32 speech at the Twentieth Party Congress 33 covering Stalin's trespassing I brooded on how great Stalin's role was in defeating Germany. Alas, my thoughts were very wistful. Even now we don't know for sure how many casualties we had in that war. It is known that the Germans had nine million casualties. [Editor's note: regarding different resources, battle casualties of the USSR were between 8,6 and 13,6 million soldiers, of Germany between 3,45 and 4,75 million soldiers. Total military casualties of World War II in Europe number between 27 and 55 million people.] Germans are very punctilious, they consider everything. We still don't know the exact figure; all we know is that it considerably exceeded the casualties of the Germans. It should have been vice versa. They were assaulters, who were supposed to lose more than the defenders. People say that 30 million soldiers perished. But this figure is unrealistic. There were so many unburied soldiers. At present people are still finding human bones when they dig in the kitchen garden. Our state doesn't look into the issue of their burial or collecting data about them, some other people are doing that.

I consider it to be amoral for the state to treat people who defended the country, the way it does. During the defense of Kiev in 1941 the Germans captured three armies, 600,000 people. There is a story line about the Stalingrad battle 34 and 330 captured Germans, and there is nothing said about those 600,000. Our army was decapitated during terrible pre-war repressions. When they talk about genius commanders, who won the war I don't agree. Of course, they played their part, but the victory was gained at the expense of the soldiers, millions of their lives. There was nobody at the head of command at the beginning of the war. Junior officers became regiment commanders. Their careers were made during the war.

When Stalin understood that the war was to turn a different course, he released the remaining commanders from the Gulag 35 e.g. Rokossovskiy 36, and appointed them as commanders. Those who became generals and marshals by the end of the war began the war as lieutenants and captains. Having believed that Germany would be our ally, Stalin started to rearm the army at the end of 1940. When the Germans attacked, our army was in the middle of rearmament. Many of the large military plants were on the territory, occupied by the Germans. Only in 1942 weapon production was launched at the evacuated plants, e.g. Ukraine. Production was also implemented in new places, but it was a time-consuming process. Then arms, tanks and jets were produced in Ural and Siberia. Before, the ammunition consisted of rifles and guns dating back to World War I. [Editor's note: it took more than a year to move the plants from the center of the USSR to the East in order to launch production of new armament. Prior to the year 1942 the Soviet Army was armed with the kind of weapons and machines which were used in World War I.]

After the war

I still remained in the army for another year after the war was over. I was dispatched to Western Ukraine. Banderovtsi gangs [see Bandera] 37 were in full swing at that time, and many military officers were sent there to fight against those gangs. We had the battle experience which the graduates of the military schools didn't acquire. The front-line experience was very important as the situation back in those times appeared belligerent. In a year the division commander called me and suggested I should stay in the army as a career officer. I said that I wanted to continue studying. The commander said that he understood me and sent me to the physical examination board. I still keep the old certificate of the medical board, where it was stated that I was banned from military service. I showed that certificate and I was qualified restrictedly fit. So, I had the chance to be demobilized. Otherwise, I would have had to stay in the army.

I came back home. I forgot everything I had learnt in school. I entered the preparatory faculty of the Moscow Mechanics Institute, which became the engineering physics institute. I entered the institute the following year. Though there were some problems. I was given a considerably lower mark for the entrance exam in mathematics. I still was accepted, in another department though. I submitted the documents for the engineering and physics department and I was accepted to the instrument making department, where the competition was lower.

When I was a sophomore student I bumped into the mathematics teacher who had taken my entrance exam. He came up to me and apologized for giving me a lower mark. I was so taken aback that the only thing I could say was that I was OK studying at another faculty and regretted nothing. I cannot say for sure, but I think that case referred to anti- Semitism, I don't have any other explanation for it. Anti-Semitism wasn't displayed during the years of my studies, though I knew it existed. A different attitude towards Jews could be felt after the war. Anti-Semitism was streamlined with the commencement of cosmopolitan processes in 1948 [see campaign against 'cosmopolitans'] 38. At that time I thought that the process was against certain scientists and cultural activist, not against Jews in general.

I think my parents felt the jeopardy of what was going on. My mother worked at the Ministry of Foreign Trade and she was offered to work in the Ministry of Internal Affairs. When she told my father about it he said that she should flatly refuse although the offered salary and position were better. My parents' job was connected with secretive and sensitive materials. Every time they were supposed to fill in certain forms to get access to these materials. During the war and for some time after the war, my father worked in the Ministry of Defense Industry and Armament, and then he was transferred to the Ministry of Heavy Industry. He worked there until his retirement. Once my mother filled in a certain section in the form regarding her relatives living abroad and wrote that her elder brother had lived in the USA since 1905. The head of the special department called her in and told her to rewrite the form without mentioning a word about her brother. It shows that they treated her in a good way and that she was appreciated. When she was to be awarded with the 'Medal for Distinctive Service' in 1948, she was the only one whose name was crossed out from the list of nominees. She was given a medal instead of this order. [Editor's note: the 'Medal for Distinctive Service' was established by the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR on 27th December 1938 for awarding those workers, collective farmers and officers who showed distinctive and exceptional results at work, who advanced development of science, technology, culture.]

In December 1952 I graduated from the institute. Father didn't retire, though he was severely ill. He needed my help. Apart from working for the Ministry of Construction, he was also a member of the municipal party committee, which was a rather high position. According to my mandatory job assignment 39 I was to go to the Ministry of Defense Industry and Armament. My father, previously employed there, called the secretary of the party committee of the ministry. I don't know the subject of their conversation; I assume my father was asking him to help me stay in Moscow. But nothing came of it. Then my father resorted to the deputy minister of the Ministry of Construction of Heavy Industry Enterprises, who called the deputy minister of defense industry and armament. But it didn't work out either.

There was no stopping my father. He had an appointment with the minister of construction of heavy industry enterprises, Reiser, one of the few Jewish ministers, and it brought no result either. [Reiser, David Yakovlevich (1904-1962): Russian-born state activist of Jewish origin. In 1953 he was the deputy minister, later minister of the USSR construction ministry.] I was sent to the closed institute of defense industry and armament in Izhevsk, located 1,000 kilometers from Moscow. I had stayed there for a year, then there was a decree of the plenum of the central committee of the party regarding 'Strengthening of agriculture' and I was offered to go to a kolkhoz 40.

The issue was very serious. I came to the instructor of the central committee of the party. I explained that I would be useless in the agricultural industry with my education in instrument building and no experience in rustic living and with agricultural machinery. The instructor listened to me very carefully and totally agreed with me. She wasn't the one who could have issued a resolution, so she called the secretary of the regional committee of the party in Izhevsk for him to decide on the spot. I had an appointment with him when I got back to Izhevsk. He was aware that agriculture wouldn't suffer a loss without me, but he unofficially recommended me to go. I was sent to a village in Izhevsk district and appointed chief engineer of the tractor station. I didn't know anything about agricultural equipment, but I had organizational skills, other issues were taken care of by the chief mechanic. I bought and established the necessary equipment, and I provided them with building materials, but I didn't have to maintain this equipment, for this purpose there was a mechanic. So I didn't have to have a thorough knowledge in production. There was a forestry nearby, and I got acquainted with the mechanic. He told me that his nephew was to graduate from the institute soon and his mandatory job assignment was to be in Kazakhstan. I suggested that his nephew should be appointed for my position as his relatives were there. He wrote to his nephew and got a positive reply. The nephew came, I told him about the functions of the chief engineer and we both went to the regional committee of the party. I introduced my successor to the secretary, and he signed my resignation letter. In 1954 I returned to Izhevsk to my previous position. In 1957 I left for Moscow, my home.

In January 1953, when I was in Izhevsk, the Doctors' Plot 41 commenced. Of course, I didn't believe the things written in the articles. I couldn't envisage a doctor, who had been treating the top circles of the government for many years, to poison people. It was a libel. Many people believed that. There were some of my acquaintances who believed that Jews would be able to commit anything, including the assassination of Stalin. There were some younger people who considered Stalin to be a criminal, who should have been exterminated a long time ago. Such talks were very hazardous at that time. We were lucky that there wasn't an NKVD stooge among us, and that we weren't arrested. Common people unconditionally believed everything they broadcast on the radio or things written in the newspapers. People refused to go to the Jewish doctors in the polyclinics. Anti-Semitism was acerbated. The street in Chernigov named after my mother's brother Jacob Nitsberg was renamed at that time. Soon, to commemorate a certain anniversary, my mother received a letter saying that she was invited to Chernigov to take the floor and talk about her brother. My mother knew that the street had been renamed. She didn't even answer the letter and said she didn't want anything to do with those people.

On 5th March 1953 Stalin passed away. It was both a shock and a tribulation for me. My mother reiterated one and the same line in her letters after Stalin's death: 'How are we to live without Stalin now?' I had no such thoughts.

I remembered the Twentieth Party Congress, where Nikita Khrushchev divulged crimes committed by Stalin. I believed Khrushchev at once. I still think a new page in history was turned, removing the old one full of terror. It wasn't accepted by everybody. My father didn't know what happened at the party congress as he was in hospital. When he was discharged from the hospital, he went to the central party committee and read a publicly closed letter with Khrushchev's speech. My father was so astounded that he stayed in bed for a few days feeling unwell. Father saw things happening around him and he wasn't so gullible not to understand what was going on. After perestroika 42 they started publishing the list of people who had been shot [see Rehabilitation in the Soviet Union] 43, where I found many familiar names, former employees of my father. He might have stuck to the opinion of the majority that Stalin's surrounding was to blame, not Stalin himself. There are many people nowadays who disbelieve the repressions, the fact that millions of innocent people had been shot and exiled to the Gulag. Mother told me that after the exoneration many people came back to the ministry. When my mother asked her former employee who was falsely convicted and imprisoned for 14 years, what had happened to him in the Gulag, he told her to ask no questions. I can only imagine what horror he had to go through if he didn't want to recall things.

After the Twentieth Party Congress I was sure that our life would dramatically change for the better. Of course, certain things changed. We didn't have to fear repressions. One could speak his mind; anti- Semitism slightly faded in every day life, though it remained on the state level. When I came back to Moscow in 1957, I wasn't able to find a job. My name was Russian, and I didn't look very Jewish. When I came to the human resources department I was offered a job, and after I filled in my nationality in line #5 [see Item 5] 44 I was apprised immediately that the position wasn't vacant any more, and that they'd just forgotten about it.

I took pains to be employed by the construction bureau of the non- ferrous metals plant Tsvetmetavtomatika. Then I was assisted in the transfer to the scientific and research institute of heating appliances. My non-Jewish surname complicated my life. Very often I was offered interesting and more lucrative jobs, and when they saw the line with my nationality, they backed off. Once my mother told me that there would be a new committee by the Ministry of Foreign Trade and there were vacancies. She kept me informed and told me to go there for an appointment. I was received by the deputy head of the committee of the Ministry of Radio Industry. He told me about the field to be involved in, and what I would have to do, and then asked me a question, 'Is there anything bothering you?' He must have noticed my tension and then asked me another question, 'Are you Russian?' I replied, 'No.' Then an explicit question followed, 'Are you a Jew?' - 'Yes.' And the last question was, 'Is it indicated in the form?' Then he told me that such issues could be tackled only by his boss. Then he added that I would have another appointment, and that the position had been taken. Things were very clear to me, and I never went back there.

Marriage life and children

I was married late, in 1961. I met my future wife, Elena Fanstein, at my friend's place. Elena was younger than me. She was born in December 1933 in a town outside Moscow called Noginsk. Elena's father, Emmanuel Fanstein, was chief accountant of the powder plant in the city of Roshal. Elena's mother, Basya Fanstein [nee Ostrovskaya] was a housewife. There were three children in the family: the elder son, Valentin, born in 1929, Elena and the junior, Leonid, born in 1939. At the beginning of 1941 Elena's father was arrested. There was an arson at the powder plant, probably caused by technological malfunction, but the whole management of the plant was charged with arson and sent to the Gulag according to article #58 of the criminal code. [According to this article any action directed against upheaval, shattering and weakening of the power of the working and peasant class should be punished.]

During the war Elena's family was evacuated to the town of Yaloutorovsk, Tumen oblast [about 1,800 km from Moscow]. It was a very hard time for them. Elena's parents lived in the town of Rouzhin, Zhytomyr province. Her grandmother died before the war and her grandfather, Shalom Ostrovskiy, objected to evacuation and was shot by fascists along with other Jews of Rouzhin in 1941. Then Elena's elder brother was taken to Moscow by his relatives, and they assisted him in entering a vocational school. After the evacuation Basya moved to Moscow with the two younger children. Elena's father was pardoned in 1945, but he couldn't join his family as he lived in exile for a while. However, he surreptitiously visited them in Moscow. Then he came to Moscow and found a job connected with business trips. Frequent trips gave him an opportunity not to attend political classes and general meetings.

Elena finished school and entered the engineering and economic institute. After graduation she stayed in Moscow and had a mandatory job assignment to a design institute to work as an economist. Her elder brother tried to enter Moscow University [M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, the best university in the Soviet Union, also well-known abroad for its high level of education and research], but it was unrealistic for a Jew to enter such an institution. He graduated from the polytechnic institute and worked as a researcher in the scientific and research institute. Elena's younger brother made an attempt to enter the institute of military translators, and didn't succeed. The following year he entered the textile industry institute and then worked as an engineer. Elena's elder brother's wife gave birth to a girl in 1959. Their daughter was named Marina. Leonid, the younger brother, had three daughters: Elena born in the first marriage in 1961, and another Elena, born in 1970, and Alla, born in 1976, in the second marriage. Both brothers lived in Moscow. Valentin died in 1994. Leonid immigrated to the USA in the 1980s with his family. They have a happy life in San Francisco.

Our wedding was ordinary. We got registered in the marriage registration office and had a wedding party in the evening with our kin and friends. We lived with my parents. Father died a few months after our wedding. He was buried in the city cemetery. Of course, the funeral was secular as my father had been an atheist and a party member. He kept on reiterating why I didn't join the Party and wondered if I hadn't changed my mind.

When my father was still alive he asked the local authorities to give him another apartment. Our apartment was on the fifth floor and there was no elevator. It was hard for my parents to walk upstairs. Father was offered other apartments, but those were worse than ours. After my father's death we were given an apartment in the residential area of Moscow. The house was located not very far from the metro, and there was an elevator. Of course, that apartment wasn't equal to ours, but we agreed to it, because of the elevator. We still live in that apartment.

In 1963 our only daughter, Victoria, was born. Elena kept on working. Mother was retired at that time and helped us raising our daughter. Victoria grew up like other Soviet children. She went to school, joined the Oktyabryata, the pioneers and the Komsomol. My mother spent most time with her. My wife and I worked hard and were pressed for time. We tried to spend the weekend with our daughter. We went for a stroll, to the theater and the circus. My mother died in 1981, the year when Victoria finished school. We buried her next to my father in the city cemetery.

After school Victoria entered the Moscow State Medical Academy of Veterinary and Bioengineering named after Skryabin. She got married during her last year of studies. I don't want to talk about her husband, as those recollections are hurting. Victoria's last name remained unchanged after she got married, but her son, born in 1988, was given the surname of his father: Bogachev. When my three-year-old grandson was asked in the kindergarten, 'Who is your dad?' he replied, 'Grandpa.' Victoria stayed in Moscow after her graduation. It was difficult for her to find a job, but her friends gave her a hand.

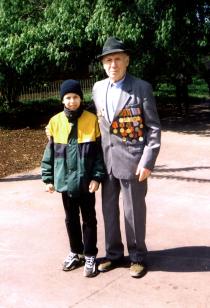

When our grandson, Artyom, was born, Elena retired so that she could help our daughter. I tried to spend my spare time with Artyom. The boy needed to have a masculine upbringing because he wasn't very fortunate with his father... Of course, Grandpa couldn't be the father, but I tried my best for my grandson not to feel that he was forsaken by his father. I love Artyom very much and I think he loves me, too. Probably I didn't raise him properly. I brought him up the way my parents did. My grandson is different from his coevals. He knows a lot about the Great Patriotic War from my tales and from many books he read. My daughter didn't have an easy life as we brought her up way too intelligent for nowadays - not pushy. Artyom is like that as well. What can we do? Would it be better if we raised a mean person who would do anything to achieve the stated goal? His life would be difficult. I know it from my own experience. Because I'm the same, and I'm not going to change. I didn't betray, did no harm to anybody. I have a clean conscience with myself and with my kin. That's the most important. My grandson is with me, sharing my principles. Once, my grandson and I were walking together, and one woman said to my grandson that he was lucky to have such a grandfather. I replied that I was a happy grandfather for having such a wonderful grandson. Now Artyom is 16. He is in the tenth grade. In a year he will have to choose his profession. I hope he will be happy.

I had trouble in my life for telling the truth all the time. Many people disapproved of it. If I heard about things impartial I always stood up for justice to prevail. I couldn't ask for myself, but if others needed my help I fought tooth and nail. Of course, there were a lot of ill-wishers because of that. Now, to crown it all I can say: no matter that I haven't achieved anything in life, my conscience is clean. I did no malice, and was not envious. My mother takes credit for that. It was she who taught me those things. There is a certain moral boundary that I will never step over. Any decent person is a friend for me, I cut indecent ones dead, I just don't communicate with them. I can understand and forgive many things, but not betrayal.

We used to celebrate birthdays of our family members and Soviet Holidays - 1st May, 7th November [October Revolution Day] 45, Soviet Army Day 46, New Year's Eve, but the most festive occasion for us was 9th May, Victory Day 47. The whole family goes to the Grave of Unknown Soldier, where we meet with front-line soldiers. My grandson has attended since the age of three. The rest of the holidays were just mere days-off - an occasion to get together with friends and have fun. We danced, sang, and enjoyed having a chat with dear people. Neither Elena nor I thought of the gist of the holiday.

Recent years

In the 1970s mass immigration of Jews to Israel started. I sympathized with those who wanted to immigrate. I helped my friends, who were on the verge to change their lives. I didn't want to leave, though my wife craved for it and even insisted on our immigration. At that time her younger brother left; and Elena thought he was right as he did it for the sake of the future of his children. Many people didn't understand why a well-off person gave up an apartment, a car, work and left the country for uncertainty. I didn't have a wish like that. I think my upbringing was the reason for it. Besides, my mother was flatly against immigration, and I didn't want her to stay by herself.

I was very keen on the things going on in Israel. I followed the news in Israel and was interested in the life of this country. Israeli people are worth respecting and admiring. They made the country flourishing, achieving the highest level in medicine and science. This small country surrounded by adversaries, has a good defense system against assaulters. In 1967 the Six-Day-War 48 was unleashed, and then in 1973 there was the Yom Kippur War 49. The term 'Israeli military clique' appeared in our press, and I disapproved of it. Common people sympathized with the Israeli struggle. They understood that it wasn't Israel that unleashed war and admired its blitz victory in that massacre.

At the end of the 1980s Mikhail Gorbachev 50, General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party Central Committee announced perestroika. I didn't take him seriously, thought him to be a prattler, who couldn't even answer questions properly. Of course, we felt certain fruits of perestroika. Liberty was obtained. We were able to get previously banned literature. Libel in the press was over. Any person could go abroad without an approval from the regional party committee, and we could also invite foreigners. We were bereft of those rights during Soviet times. Now we had the opportunity to profess any religion we wanted. Synagogues and churches opened up. During Soviet times there was only the constitution and that was it. After the first year perestroika began to decline to a certain extent. I understand that the former party nomenclature tried to clutch at the past and put a spoke in the wheel. Preposterous things were going on - elite vineyards were exterminated in the Crimea under the pretext of struggle for teetotalism. Certain campaigns commenced and then were done away with very rapidly. Then it happened so that in Moscow products started vanishing from the stores like during the war times. Food cards were introduced. Then there was an outbreak of unemployment. People of retirement age were fired. All those things brought the breakup of the great and powerful state of the USSR [1991].

I was not to be fired. In 1990, I decided to retire, when I turned 65. I wanted to spend more time with my grandson, and start enjoying my life. I have been offered to come back to work for five years since my retirement. The management talked me into it in the year 1995. I am still working.

After the breakup of the USSR my life has been getting better gradually. Of course, we have a hard living nowadays, and I'm worried about the future of my grandson. What a nuisance, our country having defeated Germany in World War II, is considerably lacking behind in many spheres. Those people who fought against Germany receive compensation from Germany, but not from their country.

I think that young people are supposed to know their history and the history of the most terrible war in particular, as well as the storyline of the extermination of an imminent global fascist dictatorship. There is a railway college in Moscow where one of the regiments of our division was formed during the war. Now it is a museum of our division. I have been attending it for many years and held speeches on 'Classes of Valor.' For the first time I went there with the chairman of the war veteran council, a former party activist. When he took the floor, I noticed that people weren't listening to him and paid no attention. He was talking of the things that could be read in any textbook, so the story was thin for them. Then I took the floor with the stories about my front-line experience, the same I told my grandson, and they displayed an interest. I understand that they were aged 15-16, and I was a little bit older when I went to the front. I understand them, their problems, even though I'm an elderly man. I went there for many years, but now there are no classes of valor in their curriculum.

During perestroika the [Moscow] Council of the Jewish War Veterans 51 was founded in Moscow. I became its member. It was about 15 years ago. I have been the presidium member of this council for many years, and worked in the group of assistance to the needy. I paid a lot of attention to seeking those who needed help. Then, when I came back home, I rejected that position. I cannot just be there and do nothing. I had no time for that.

The first time I came to the synagogue was also during perestroika. There was only one synagogue for the entire city of Moscow after the war. The most ancient synagogue, and the only acting synagogue during the Soviet regime, was located in the heart of Moscow, on Spasoglinichevskiy Lane. The synagogue was ceremoniously opened in 1989. Now it is called 'Sinagoga na gorke' ['Synagogue on the hill' in Russian]. Then another one was restored at Malaya Bronzy. I've been very aloof from religion all my life. It was the way I was brought up by my parents and it was too late for me to be re-nurtured. I got to know our rabbi. He is a very interesting man and we both enjoy each other's company. We don't broach religious subjects, there are other common topics we find. We used to attend concerts of Jewish songs, but then it got more difficult for me to go because of my health problems.

Recently a new Jewish public center has been built. Many interesting people come there, including journalists and writers. I was there once, and I like it very much. We also have a Jewish charitable organization, Hama [Hesed] 52, which is very helpful to people. Unfortunately our Jews enjoy receiving more than giving. When I worked for the Council of the Jewish War Veterans, there was one entrepreneur from Pyatigorsk, who organized our trip to Israel. He paid for our round trip, and we had to take care of the accommodation. I've always dreamt of going to Israel. My daughter gave me the money and also informed her acquaintances that I would stay with them. I didn't have a foreign passport, and I was enrolled in the last group to have time to process the necessary documents. I was the head of the third group, where we selected people who were involved in the work of the council. But there were people who had nothing to do with the council and asked me to send them to Israel just because they had some relatives there. We tried to explain our selection process but heard their indignation in return. I understand that all bread is not baked in one oven. But why are there so many mercantile people among the Israeli? By the way, I didn't manage to go to Israel, some of the members in the second group refused going to the airport by electric train and wanted the sponsor to cover taxi expenses. The sponsor was so perturbed that he said he would do nothing from now on. Our group had Israeli visas, when we were apprised that our trip had been cancelled. So, I didn't go to Israel in the end.

I would like to live long enough to see Russia a civilized European country. I would be happy not to see things overshadowing our country. I would like my grandson to find himself in his life after he finishes school. I would like that useless blood-shed in Chechnya [see Chechen War] 53 to be over. Nobody knows what for somebody's grandchildren perish. And the most important is for our children and grandchildren to know about war only from tales of such veterans as I am.

Glossary: