Inna Shkolnikova

St. Petersburg

Russia

Interviewer: Inna Gimila

I was born to two university students in 1936 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. My

father, Boris Nekrasov, was a graduate student and had been exempted from

army service. However, during the first few days of the war in 1941, he

left for the front voluntarily and was killed in the battles above Rostov

na Donu on January 23, 1943. I was 6 years old. My mother and I were

standing over the oven; Mother wore a white wool shawl over her shoulders.

Mother stroked my hair and said, "Now we've been orphaned." The room was

terribly quiet; all was like stone. At that moment I still hadn't realized

the full horror of what had happened. I cried bitterly after a few days

when some boy hurt my feelings; I thought, if Father was still living, he

wouldn't have let that happen.

My mother, Lyubov Danilovna, a 24-year-old widow, was left with not only a

6-year-old on her hands, but also with her paralyzed father, Danil

Aaronovich, and her mother, Eva (Hava) Leibovna. Mother was at this time,

even at such a young age, the director of the Tashkent evening school. The

students were injured soldiers who had been evacuated far from the front

lines to a place where the climate was good and there was fruit. In

Tashkent, the rehabilitation of soldiers was quick, as was their return to

the front.

Grandmother Hava at that time was 58. She was very talkative and kind, just

like my mother. She fed all the students who came to study at our

apartment, and saved all the neighbors by lending them money, even when she

had little for herself. My mother was the same. Uncle Aaron and Aunt Sara,

mother's older brother and sister, were serious, interested only in

scientific research. Even though Grandmother only finished two classes of

Hebrew school, she read as lot and had a wonderful memory, saving me

several times when I couldn't finish assigned readings on time. She

imparted her love of books and knowledge to her children: Aaron and my

mother attended a literary society that was run by Yaroslav Smelyakov, a

famous Russian poet. After the war the society was held at the House of

Scholars. The library that my parents collected contained more than 2,000

books. My husband and I collect books on art. Before the war, Grandmother

Hava and the children would take vacation to Cherikov. She was even in the

Crimea in 1916.

We dressed modestly in a European style. Grandmother mostly wore a dress

with a white collar when she went out. For everyday wear, she wore a skirt

and a sweater. Since Grandfather's brothers moved to America in 1920 and

sent help from there, Grandmother bought a hem-stitching machine at the

Torgsin store and decorated all her shirts, tablecloths, napkins and

pillowcases. No one was allowed to come close to the machine, even thought

the desire to "spin" the machine was great.

In our house, there often were puppet shows for children. I think this was

the Purimspiel tradition. Even though we have no grandchildren, we hold

celebrations for our neighbors' children to this day.

Our house always had fresh bouquets. The windows began to fill up when

Mother retired. Father worked in the Botanical Gardens in Tashkent from

1938 to 1941 and had his own plot there where he grew apple trees. Father

always brought flowers home. Once he brought home a basin of roses. Mother

was given flowers by her students. We gave them to each other on holidays,

buying them in stores and from street vendors.

The only decorations in our house were a marble table with a samovar on it,

a mirror in a big frame, and a buffet. The table was always covered with a

flaxen tablecloth embroidered with blue flowers. Uncle Aaron was a

geologist and roamed from expedition to expedition. He had temporary

lodgings. Aunt Sarah, Mother's older sister, was a doctor and had her own

four-room house in Tashkent. It also had an office for her husband, a big

porch, running water, a toilet in the yard and a garden. There was Nanny

Dusya - the children called her Marusya - who did housework, and her father

who was the gardener. Her father, a German, had sold all his belongings to

purchase a machine that printed money, but it only printed 10 bills and

then broke. Dusya was a Russian woman of about 30, who studied in the

evenings to be a nurse, fed the children and walked with them because Aunt

Sarah's younger daughter, Natasha, was diagnosed with cerebral palsy and

needed specialized care. At that time there were no wheelchairs or braces.

I don't know why, maybe because our family was surrounded by Russians and

Uzbeks, but in our house Yiddish was only spoken when the adults wanted to

hide something from the children. In those situations, I would say,

"Enough, speak properly!" and all the adults would laugh. I also remember

one song: "Der shneider shnei mid shnei." Candles and kerosene lamps were

lit so often that I don't remember any special candle-lighting. To be

honest, we would stick needles in the meter, connect the wires and "steal"

electricity, which was rationed.

Before the war, in Tashkent, the milk was brought by a milkman. He would

make a mark on the white wall of each house with a stick of charcoal and

when the stick ran out everyone paid their debt and the wall was

whitewashed. If he brought fruit, it was weighed on hand scales, with a

stone as a weight; but the measurement was as exact as in a pharmacy. We

bought foodstuffs at the Alaiskii bazaar, the biggest market in Tashkent.

During the war, we bought things with ration cards. I would stand in line

and then an adult would come to take my place and buy things, until 1946

when I was trusted to carry the cards. There was a careful science to

rationing. One had to be able to pick the best of each assortment of wares

because on one card one could buy either a half-kilo of smelt or a liter of

sunflower oil. You had to decide quickly which was better because food

wasn't always available in the stores. Lines - it feels like half my life

was spent in them. But the biggest lines were at the banya. It was freezing

in the street, then you got into the building and washed. In the building,

it was very hot, but you weren't allowed back out. Children whined. Linens

were taken to the "lice battler," and they gave you dry, warm and stinky

clothes in return. They smelled like goats, very unpleasantly. There were

some tragicomic situation: At the beginning of the war, Grandfather went to

the banya in a fox-fur coat and came back in the quilted robe of a

bathhouse attendant and someone's pants, which were too short.

My father-in-law, Abram Shkolnikov, told me that in his family meat was

eaten once a week, on Saturdays. During the war, there was no meat. We ate

little, Grandmother Hava often was in the hospital with little cousin

Natasha, and I would travel across the city to visit them and eat at the

hospital. I remember how I wanted to know what fried eggs tasted like, but

Grandmother explained that without butter they wouldn't be good. I was

stubborn, but Grandmother was right. Those eggs weren't tasty at all! After

the war, no holiday was complete without stuffed pike or herring butter,

and the teiglach and tzimmes would just melt in your mouth!

Women braided their hair and did it up in a net, while girls wrapped their

braids around their heads. All had long hair, down past their waists.

Family legend says that during the 1920s, Grandma was courted by Buden and

he gave her ribbons for her braids. This was somewhere near Ekaterinodar. I

had poor hair; as a child I would wrap a sheet around my head and pretend

it was a braid. I remember during an outbreak of typhus in Tashkent,

Grandma Hava was shorn of all her hair. And I, silly little girl, not

thinking that I would hurt her, said, "I asked you for your braid and you

said 'no.' You would have done better to have given it to me!" I was very

afraid that her hair wouldn't grow back, but she grew the braid again, and

now I have it in my closet.

Grandmother was buried in the European fashion, in a coffin in the Jewish

cemetery. They said Kaddish and the cantor sang beautifully. After Kaddish,

Mother and I had pieces of our shirts ripped off and buried.

Aunt Sarah, the professor's wife, always had outfits sewn by the best

tailors, but Mother could only afford this in the 1950s. Her students later

told me that they couldn't wait to come to my mother's class so that they

could see what she was wearing. As a matter of fact, my mother always said

a teacher shouldn't dress like a "blue stocking," but more civilized, which

pleased the children. Uncle Aaron saw nothing but his scientific work.

People laughed at him when he said satin was a kind of wool. His wife took

care of his clothing. Tailors in Tashkent were afraid of the inspectors

from the tax police and went to people's houses to sew. They were fed and

paid, not for each item of clothing, but for each day's work.

In Sarah's house there was a piano and in the evenings there was music,

especially when her neighbors were refugees - students from the

conservatory in Leningrad, including the family of the composer

Kotlyarevskovo. Her children also studied music. Even with such a posh

lifestyle for those days, Sarah, at the first call, night or day, would go

heal the sick. Grandmother loved Sarah selflessly and I really wanted to

become a doctor like Sarah.

During the war, in 1942, refugees came to us from Kharkov: Grandmother's

brother Josef with his wife, Frieda, as well as two of Grandmother's

sisters and their families and my deaf-mute great-grandmother. These 14

people fit somehow into a two-room apartment. I don't remember my great-

grandmother's name; at home we simply called her "Old Grandmother." The

grownups slept in pairs on skinny metal beds. The older boys and girls

slept on the table and dresser, and the little children on chairs pulled

together. I remember how I would run to Great-Grandmother, tug at her long,

gray, canvas skirt and, with gestures, show her that it wouldn't hurt the

bread any to be spread with pate or something else. The fact that my great-

grandmother was a deaf-mute wasn't discovered by my great-grandfather Leib

Bernstein, a Talmudist from Chernikov, Ukraine, until the day of their

wedding. Before the ceremony he had only seen his bride from far away. In

spite of this they had 12 children, five of whom lived until the war:

Hannah; Hava; Dina, a doctor; Josef, a member of a collective; and Lazar, a

jeweler. All their children were able to speak. I remember that we buried

Great-Grandmother wrapped in a shroud - as I later learned, in the Jewish

tradition. I was strolling somewhere, and when I returned home, strangers

were carrying out something thickly wrapped, shrouded, in white sheets.

Mother said that all the elders were going to bury Old Grandmother. Later,

seeing people interred in coffins, I learned that in the Jewish tradition

people were buried wrapped in material.

I truly loved kindergarten. However, during the war Mother didn't have the

money to regularly pay for it. One day they wouldn't let me in. It was

raining, Mother was crying and asking them to wait until money came in.

During the war, the officers received the money that was to be sent to

families. I didn't know about that, but I talked Mother into taking me to

school that very day because she worked there. I was only 6. This crusade

ended with my getting into a car accident - a drunken driver hit me while I

was standing on the sidewalk; he was later convicted. I was saved by the

surgeons at the hospital where Aunt Sarah was the head doctor. After the

operation I was nursed by Mother's cousin Lyuba, Grandma's sister Hannah's

daughter, and her schoolmate, Izya.

Grandmother taught me how to knit, and Mother, how to sew. During the war,

I would hide a piece of bread in my pants and trade it for embroidery

thread at a kiosk near our house from a lady from Odessa.

I was brought up by my stepfather, Mikhail Rafilovich Rubanenko - a person

of high moral qualities and intellect. He gave me not only an education,

but also sheltered my family when, in 1961, my husband was demobilized from

the Soviet Army. He gave us his 30-square-meter room, and he and Mother

slept behind a curtain in 6 square meters. Suffocating in that space, he

spent half the night in the kitchen reading books. I began to call him

Father upon the birth of my little sister Natasha, August 19, 1947, and

called him such until his death on August 16, 1991.

The school in Tashkent was a one-story building that was heated by stoves;

water stood in barrels with a cup fastened to its handle; and the toilet

was outside. Girls and boys studied separately. In the winter we went to

school in warm gowns and in the spring in summer dresses. I began wearing a

uniform consisting of a brown dress and an apron in 1948. Along with

Russian I also studied the Uzbek language. I remember how they taught us

the anthem of the USSR. We were all taken into the corridor and we shouted

out the text.

I went to school from 1942 to 1943 in thick wool socks and galoshes. In

1943, as the daughter of a killed soldier, I was given sandals that were

then taken from me by my brother Vitalik, who then gave me his old ones. In

the winter I was given boots, black ones with laces, and the adults made

sure that I didn't lose them this time. My greatest happiness was Mother's

old leather briefcase with shiny little locks. We wrote with fountain pens

and inkstands. The ink was poured into the inkstands from an unspillable

ink jar, brought into the school in a tobacco pouch and placed in the cut-

out of the desk. When the ink ran low, we added water. My pouch and socks,

which I knitted under Grandma's supervision, were sent with some other

things to the front to Father Misha - that was what I called Mikhail

Rafilovich. The factory at which Father Misha worked made projectors for

the operating lamps at hospitals, and Aunt Sarah often asked this factory

for help. That is where she met Roman Alexandrovich Gavrilov, who saved us

in 1953. She invited him to her house. This was May 30, 1943, and my

parents always celebrated that date thereafter. Gavrilov came to her house

with Father Misha; my mother also came. That is how they met.

In 1944, Mikhail Rafilovich, having left the army, was shell-shocked and in

a hospital in Yugoslavia where he was found by Aunt Sarah, taken back to

her hospital and cured. Father was a closed person, stern but very kind. In

1945 we left Tashkent for Moscow where we lived in Cherkizov in the house

of one of Father's distant relatives, the artist Ilya Lisitskovo. By the

way, when foreigners, in 1947, were interested in the avant-garde works of

Ilya, his brother Rubim went to the KGB and asked for permission to sell

the works. The comrades from the KGB came and took everything except some

toys and a few photos.

Half of the house in Cherkizov, Moscow, was sold by the owner to a

religious Jew named Solomon. He attended the prayer house in Cherkizov. I

wanted to go there and look in, but Mother explained that women and girls

didn't go there. I still went and peeked in, and saw that old men in black

clothing were sitting at a long table. On the walls there were no paintings

or icons. Where did I find out about icons? I was in a church, seeing as I

was a typical curious child and stuck my nose in everything.

The daughter of Grandfather Solomon was married to a Russian general from

Marshal Zhukov's division. In 1947, when they were dealing with Zhukov,

they came at night for my father while they searched Solomon's house. It

was summer and all the windows were open. The general's housekeeper,

Natasha, threw a packet through the window that Mother hid under her

pillow. That morning Solomon came and brought Mother a large box of the

perfume "Red Moscow," but didn't eat with us and or even have tea because

our house was not kosher. After a few days, Solomon's granddaughter, Sveta,

in disgust over her cut finger said: "What is this! Soon Stalin will even

take our skins from us." And this turned out to be true. They were sent to

Kazakhstan and Solomon and his wife died from grief. Not far off was the

famous "Doctor's affair" of 1953.

At that time we already lived in Leningrad, Father was the head builder at

the factory Svetlana when a "blacklist" was written against all the Jewish

workers. The situation was saved by Roman Alexandrovich Gavrilov - with his

own life. Going up alone against the party, local committee and other

organizations gave him a heart attack. This story was told to us by Yakov

Slavin, the head army representative of the factory, at my father's

funeral. He kept this secret for 37 years. That is how strong fear was

during Stalinist times. In 1953, my mother-in-law, a teacher of Yiddish

before the war in Belarus, not only burned all of her Jewish books, but

also her work records.

Father Misha had a daughter, Ludmilla, from his first marriage to Eva

Nevezhska, an X-ray technician. Eva died of radiation at the beginning of

the war. Ludmilla and my mother had a very warm relationship. Ludmilla -

the most sensible of us three sisters - is very well read. She lives with

her children and grandchildren in America.

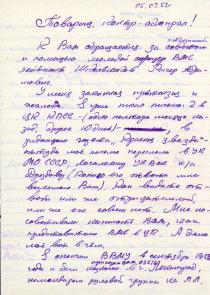

In 1953 my future husband, Grigorii Abramovich Shkolnikov, an officer who

finished among the best at the Pacific Ocean Naval Academy and obtained a

post on a submarine in the north, was removed from his post because of his

Jewish background. He was 25. He fought for justice because of his honest

soul and his belief in the Communist Party, writing a letter to the Central

Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Only the execution of

Beria allowed him to escape an investigation. The same committee that

forced him to leave the submarine offered him a position on a minesweeping

trawler, where he quickly became the navigator of the flagship and spent

468 days in the minefield of the Baltic Sea, clearing mines. He received a

medal for this 40 years later "for battling mines." In answer to his

complaint, a commission from Moscow arrived - a representative of the Navy,

Captain Ogurtsov. My husband was read the order for his assignment to the

minesweeper in the office of the assistant of the head of the naval bases,

Vanifatev. Before this, he was forced to sail on the fire-fighting ship

around the Fontanka, which was insufferable for a real submariner.

We were married in 1955, when I was 19. I was a student at the Leningrad

Institute of Film Engineers; he was an officer. As the wife of a soldier,

finding work was difficult. With the help of my husband and his comrades, I

organized courses in film mechanics in a prison camp in the city of Liepaya

- this camp was famous for a riot - and, after my husband's demobilization,

we returned to Leningrad.

I'll tell about the incident in the camp in May, 1959. The head of the club

in which my husband served obtained an agreement with the head of the camp

saying that I could teach the prisoners the profession of film mechanics.

He gave me a film projector for cinema showings of films, which he also

gave me, and I gave lessons by a set program twice a week for four hours.

The courses were first organized for the camp guards, six of them. However,

the administration of the camp had no money to pay my salary except if they

took on prisoners as students. These students would have 1 ruble per month

taken from their bank accounts for the lessons. There were 37 people, and

they paid 37 rubles. The first to come to the lessons were the convicts. I

left the class to ask the guards to come in so that I could finish the

class. When I came back into class, I saw that the tables had been moved

and the chairs had been set on them. Through this barricade I could see 37

pairs of angry eyes - prisoners who didn't want to study with the guards. I

was very scared; I had a baby at home. I calmed them down by finding a

clever way out of this situation: I said: "Do you know that I'm a member of

the Komsomol? I have to submit instructions to the secretary of the

Komsomol organization in this camp?" They gave up and in the end, we had

class with both the guards and the prisoners together.

I worked as an engineer, and Grisha, after his successful service in the

Navy, wasn't hired in the Baltic factory because of the Fifth Article and

worked in the construction bureau of the Svetlana factory. In 1987 he was

accused of being a Zionist -at that time in the group there were five Jews

and one was planning to leave for Israel, and Grisha was forced to leave

Svetlana. And we, battle-hardened by our fights with anti-Semites, began

life from nothing. Grisha began to study economy, obtained a diploma and

was employed immediately.

Father was buried on the day of the putsch in 1991, and even though he gave

51 years of his life to the factory, they wouldn't allow farewells to be

said near the factory. Many people came to the burial anyhow.

My daughter, Irina, graduated from the Leningrad Institute of Engineering

and Building, and was an architect on more than 50 buildings in Russia. Her

projects have been published in the magazine "Private Architecture." Her

husband, Gennadii Aaronovich Bekker, to enter the military academy, was

forced to change his name to Gennadii Alexandrovich Bekerov, but he didn't

want to change his nationality and the Fifth Article didn't allow him to

enter the academy. Gennadii graduated from the Textile Institute and was

recently re-elected as the representative of the municipal council of the

village of Tyarlevo.

Anti-Semitism was so widespread in Russia after the war that it spread our

family all over the world. My younger sister lives with her family in

America, my husband's sister lives in Israel, my uncle, once removed, lives

in Australia.

Our young Russian neighbor, who moved to the city from the country, said to

me: "I've been told that you're Jewish, but I didn't believe it, because

you work so hard." I answered, "Kolya, in the country, where you lived, did

you see even one Jew?" He said, "No." Do you have any questions? I don't.

It was fed to him with his mother's milk.