Golda Osherovna Gutner

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Yelena Tsarovskaya

Date of interview: November 2001

My name is Golda Osherovna Gutner I was born on August 15, 1916, in the town of Konotop, Ukraine.

Let me start with my grandfather, my mother’s father. I don’t know where he came from. I only know that he was born into a very poor Jewish family. His name was Boruch Lurye. He was a tinsmith and owned a workshop with work-hands in Konotop. The buckets and other articles they made they took to fairs. Mother told me that as a young man my grandfather was a solider. At that time soldiers were to serve in the army for 25 years. He got very sick in the army. According to my mother, the doctors told my grandfather that he should go to St. Petersburg, to the tsar himself, and get a release from the army. I don’t know who received him in St. Petersburg in reality, but he took his documents about kidney disease there; he was transferred to the reserve and returned to Konotop, to his wife. Grandfather died at the age of 48, in 1905, from his kidney disease. In those times young people created families. Grandfather was around 17 years old when he married my grandmother, Fruma-Tsivye. (I don’t know her maiden name). She was around 16 years old. She was a housewife. They had 14 children, but only six of them survived: three sons and three daughters. The eldest child was Soreh-Liba, born in 1875. Then Meishko was born 1888, then Rakhil and Avram were born, and Shlemka was born in 1899. I have practically no memories of my grandmother Fruma-Tsivye, because she died at the end of 1918-1919, when I was too young.

Keeping order around the house of such a large family and feeding the workers of – all of these duties rested on the shoulders of my grandmother Fruma-Tsivye. They also had cows. Their children certainly helped the parents. Everyone was working. They owned nothing but the workshop. Aunt Soreh-Liba, for instance, soldered together with her father’s workers.

Soreh-Liba, the eldest daughter of my grandparents, married a worker from grandfather’s workshop – Vengerov. They were in love with each other; when he was in the army, she waited for him. After grandfather’s death Vengerov owned the workshop. Brothers Meishko, Avram and Shlemka first worked for Vengerov. But Vengerov had a difficult character, and the brothers organized their own workshop. They were great friends. Unfortunately, Meishko was a sportsman and died at the age of 37 because of a heart disease. Then Avram and Shlemka began to provide for his family (two daughters and wife Beilya). Soon, Avram got sick with leukemia. He died either in 1932 or 1933. He left son Boris (named in honor of grandfather), daughter Fruma (named in honor of grandmother), and the wife. So, Shlemka alone provided for his own family and the families of his brothers. My father said that his ancestors came from Austro-Hungary. His grandfather was a rabbi (I don’t know his name). He was somebody special – he was buried in a crypt, with a lamp always burning in it. That rabbi had three sons. One of them was my grandfather, Ele Gurevich. His brothers came to visit us from Kharkov in 1920-s. I was named in honor of father’s grandmother. My mother said that my great-grandmother Golda came to visit us too. She liked to drink tea very much, so she always carried her own kettle with her and asked people to boil tea for her only in this kettle. As she was drinking tea, she always said in Yiddish, “Grandmother Golda loves tea”. Grandfather Ele Gurevich was a watchmaker, and his wife, grandmother Sima – a housewife. Besides my father, they also had daughters: Fanya, Liza, Gita, and son Shura (Mulya). They lived in the town of Radul, Belarus. During the Civil War there was a White Guard gang, so around 1921-1922 they moved from Belarus to Konotop (because life was quieter here). In the beginning, they lived with us, and then uncle Meishko found a flat for them and a little store where they opened a coffee-shop. All of this was during NEP∗.

Grandmother Sima was a brunette, but already grey, while grandfather was blond. He had a beard with grey hairs in it. My father looked like grandfather, but he was brunette; and I look like my father. I have the same form of the nose like my grandfather. Grandmother was a tall thin woman, who always wore long skirts, reaching her heals. Nobody else dressed like this in Konotop. She never wore any wigs, and I don’t remember anybody else in our town who would wear a wig. My grandfather wore regular clothes. On his head he always wore a yarmulke, but I remember he always wore a cap on top. When he came to us, he took off the cap, but left his yarmulke on. Grandfather visited us often. He liked playing with us. We played cards a lot. I remember when I was young and played him, if I lost, he always hugged me and laughed heartily. Grandfather died around 1928, but grandmother Sima died first. I think she died because of pneumonia. When grandmother was buried grandfather got sick. He was rushed to the hospital. I remember visiting him there, bringing him food, and he looked very content. Around 3 weeks after grandmother’s death he also died. I remember his funeral very well. He lied on straw and was buried without a coffin. His grave was covered with wooden boards. Then we took off our shoes, which is called “siveh” [this Jewish rite of farewell with decedent- seven days of mourning], and sat on the floor for the whole week (I exactly not litter what it is. Know only that was beside Jews such tradition). Gradually, these traditions died away. When my grandparents died, special white shrouds (“takhrikhim”) were sewn. Special people sewed them by hand. But afterwards there were no such people any more. However, when in 1957 my father died because of cancer, such a “takhrikhim” was sewn for him, and he was wrapped in a taleth (a special cover for Jewish men during prayer), and a costume was put on top of it. By the way, we took this taleth to evacuation with us.

My father, Osher Isaac Elevich Gurevich, was born in 1883 in Belarus. There he got his education. I think he finished a cheder and then learned Russian on his own, this was it is required for life and work. He was a very good tailor. My father sewed clothes for men: coats, special costumes, and military coats for officers. After the revolution, father worked in an artel for some time, but he did not like it there. So, he began to work alone and pay taxes. Before the war, in 1930-s, he got some additional training and began to sew for women, because, he said, women always ordered more than men. When he was young he never sat at one place for a long time, but lived and worked in different places, and in the beginning of the 20th century he found himself in Konotop. Father grew up near the Dnepr River. He was a good swimmer and an oarsman. In Radul, their house stood almost over the river. When revolutionaries had their meetings, my father helped them cross the Dnepr. He was huge and was often standing on duty for them. Right before the October Revolution, father rescued some revolutionary in Konotop. He put that man among the workers of his workshop, and the tsarist police did not find him.

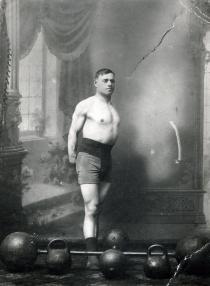

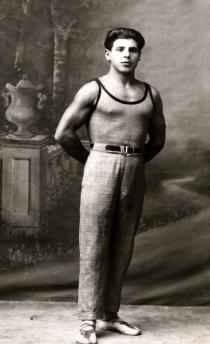

My mother, Chaya Lurye, rented a small store and traded in various small articles there. In that store she met my father. Then my father met mother’s brother Meishko. They became good friends. Brothers liked sports very much – there was a “cult of muscles” in the family. Every time a guy would come to ask for my mother’s hand, Meishko, as her brother, would always try that guy’s jacket on. If the jacket was small for him, it meant the guy was not developed physically enough (this was general jacket, Meishko wanted that husband daughter's was physically strong person, either as this himself). Gurevich’s jacket was too big for Meishko. My parents married in autumn 1907. I not know was beside them wedding. My father was a raven-head with black eyes.

He was not a party member, but he sympathized with revolutionists. Probably due to being a good tailor, he had to work for his boss (when I was born he already had his own workshop with hire-hands). But he always said, “A boss is a boss”.

My mother, Chaya Borukhovna Lurye, was born in 1885 in Konotop. She was not tall; she had blue eyes and blond hair. I think she finished cheder, because she was quite literate in Yiddish. I also think she learned Russian on her own. Just like everybody else in the family, she was quite religious; she had a special seat in the synagogue. When she went to the synagogue, she wore a special outfit. I remember she had a scarf, which was beautiful. Mother always celebrated all Jewish holidays. She was a fanatic before the war, but not after the war. We never ate pork at home. We always prepared to every holiday. In autumn she bought geese and fed them well until Passover. Before Passover, no matter what the weather was, she hired somebody to whitewash the whole house. Then she cleaned the house of all “khumyts” (leaven; according to the Jewish tradition, there should be nothing made of leaven in the house on Passover). We had special crockery for Passover. We always made special Passover wine of cherry. My mother made huge jars of such wine. My grandparents would come to the first Passover seder. We all sat around a big table, and there were a lot of delicious things on the table – so many that I don’t even know how people could eat all of them! There was stuffed fish and other delicious things. Foods for the whole Passover week were cooked on geese fat only. My mother also had a lot of pans and she cooked things with fat, with flour, with poppy, and with matzos. Special people (I not know who were these people, but think that they worked in synagogue) baked matzos for Passover. At the seder, my father sat on special pillows, and brother Boris asked the four traditional questions (he studied in cheder for some time, but there were no cheders after the revolution). For the whole evening people would sit there, eat and tell interesting stories. All of this was done in Yiddish. We all spoke Yiddish at home. Yiddish was the native language for all of my relatives. I also remember there was a holiday when a chicken was rotated over head. Mother would give us all chickens, then she would put them in a basket and I went through the town to shoichet (Jewish ritual butcher). Mother told me how a chicken’s head should be put under the wing so that there would be no blood. She trusted me with money to pay the shoichet, even though I was only ten years old. But we were very independent at that age; mother taught us to do everything: clean the flat, wash windows (every ten days), clean the dust, and wash every leaf of the plants we grew (she liked them). We baked bread every week. She bolted flour and made dough, and I had to knead dough with my fists. I once asked her, “How long should I be doing this?” and my mother answered, “Until beads of sweat appear in the other corner of the room. Every Friday we did a major cleaning of the house.

Mother was a housewife. She only hired a babysitter when she gave birth to two twins. When I was born there was no babysitter. There were no water pipes, and when we had to wash we brought water from the well. In summer we carried water ourselves, but in winter we hired a special man. In winter we washed clothes in the river in ice-holes. We carried things on slides. We always were clean. We also washed in bath once a week.

Mother had very good music ear – she sang and danced well. When she was young she was invited to Jewish weddings that it there sang. In Konotop she’s all knew and much liked to listen as she sings.She liked both Jewish and Ukrainian songs. Aunt Soreh-Liba’s son once said, “When aunt Chaika comes, no actors are needed – people will be listening to her alone”. My father could not sing, but he liked singing. He even sang in a choir.

In 1908 my mother and father had twins: Boris, named in honor of grandfather Borukh, and Ida. For some reasons they were always ashamed of admitting that they were twins. Eight years later I was born. At that time our family stayed at the house of a rich Jew, Kozlovsky. His house was located downtown. It was a two-floor good house made of bricks with a big yard. It also had two courtyard houses. I remember horses in the yard. The main house had two big good rooms. My father’s workshop was located in one room, so workers were sitting there. But during the Civil War, the military occupied the whole house. My mother found a place for us to live on the outskirts. We settled in Yarkovskaya Street. It was an absolutely Ukrainian street, with only a few Jewish families. There was no anti-Semitism in Konotop prior to the war. My mother had Ukrainian friends, whom she knew from her youth, and they spoke fluent Yiddish with her (they little knew Yiddish, therefore that always veins amongst Jews). Among the Jewish families was the family of Tsitovskies.. Their son, Chaim, born in 1920, was awarded the title of the Hero of the Soviet Union for crossing the Dnepr during the Second World War. I think he is the only Hero of the Soviet Union who was born in Konotop. The museum of Konotop has his portrait and a memorial board. My mother’s brothers with their wives often came to visit us. We had a large hall where we all played and ran after each other. They had families, but they still ran after each other like kids. There were no TV, radio or lights then, so it was the only entertainment. Sometimes we also played cards. My father liked to eat sunflower seeds when he talked to somebody.

There was a club of handicraftsmen in Konotop. Jew Topkin was in charge of that club. My father always attended this club in winter and took me with him. Topkin delivered lectures. There was also a good drama theater in this club. They staged various plays. I also recited a poem on Lenin’s death in that theater and was awarded Lenin’s portrait for this. The Jewish theater of Zaslavsky came to Konotop. They showed “Tevye Tevel” by Sholom-Aleichem all this occurred indoors club. My parents took me with them to watch it. Some other famous actors came to our town. I think it was in the middle of 1920-s.

Konotop was a small town, but there were a lot of Jews there. There were 4 synagogues in it. The Jews were chiefly found in the center of the town. There were many tailors and shoemakers among them; also there were those who fixed bicycles. The division into rich and poor was very strong. The rich had their own stores and two-floor houses, but the rich ones often helped the poor ones. We were quite poor (life was better only right before the war). The most difficult years were the 1931-1933-s. In order to survive we sold articles made of precious metals and bought some foods instead.

At home we spoke only Yiddish before the war. My brother even went to cheder before the revolution. When I was young, there were Jewish schools in Konotop, but I went to a Russian school (even though most of the students in my class were Jewish). I finished 7 classes. I also learned music for 6 years (parents bought a piano from our neighbor). After school I finished a one-year accountancy school and since 1932 I was working as an accountant in a flax-storing company.

All Konotop boys, just like my brother Boris, were trained in Vengerov’s workshop. My brother studied metalwork in this workshop for several years. Then he said he wanted to continue his studies. Vengerov supported his idea, considering him very smart. My brother dreamt of studying in Moscow, but my mother did not like Moscow for some reason, and in around 1929 my brother Boris went to study in Kharkov, to aunt Rakhil. In Kharkov he worked at a plant as a tool-maker and simultaneously studied at the Workers’ Department . Then he entered the Heavy Engineering Institute. My parents could not help him financially, for these were the difficult 1930-s. He lived in a dormitory on his scholarship. He was a good student. He graduated around 1936. He was sent to work in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg) to the “Uralmash” plant. From that plant he was sent to Leningrad, to the Higher Military Academy, where he studied for another two years. From there he was sent to Kramatorsk, where he worked as an engineer up to the beginning of the war.

In 1933, my sister got married and moved to Kiev. I also wanted to live in a big city. In March 1937 I moved to Kiev. I lived with my sister and worked as a bookkeeper at a paintwork base. But I did not work there for long; I moved on to another organization, “Spetstorg”, where I also worked as a bookkeeper. This organization serviced exclusively the military. This organization sent me to Lvov in February 1940. I liked Lvov very much. (Just like other western regions of Ukraine, Lvov was part of Poland until 1939. In 1939, these lands were annexed to the Soviet Republic of Ukraine). I rented a room from a landlady, who treated me very nicely. I was young, I was not even 24 years old. I would go to different places, like dances, and I had many acquaintances. One of them was a military man. There is a wonderful park in Lvov – Stryisky. He and I spent June 21, Saturday, in that park. The next day he invited me to the Opera Theater to a ballet. In the morning next day I woke up from a sound of thunder. I thought to myself, “Oh, if there is thunder, it means it is raining, so how will I go to the theater?” I opened my eyes and saw the son shining. So, where did the thunder come from? Then I heard the landlady crying, “German has attacked us!” They called “Germans” – “German”.

Her husband left the day before and went to another town. They had two boys, Monek and Manek. It was a good Jewish family. The landlady was begging me to take them with me. I began to cry. I wept a lot on that day. That military man came to me and said, “Leave everything and flee immediately. Our men left in nightgowns, with only wives and children”. I spent that night in a shelter. I was the secretary of the Komsomol organization, so I was naturally waiting for some instructions. But my chief accountant, Natan Markovich Fridman, was a very good man. He told me, “Pack immediately and we will leave together”. We went to the train station. It was impossible to get on the first train, because its doors were locked. Our coworker Ostrovsky went to see us off. He found an open window in the second train, even though the doors were barricaded by suitcases. He opened the door to let people get on. We also took the sister of our chef; they came from Leningrad. Thus we left: no tickets, no money. Natan Markovich was a decent man. We could have gone to any canteen that belonged to our organization and taken some money. But neither he nor I did that. We left Lvov on June 23, in the evening, and arrived in Kiev on June 27. We stopped at every station; there were a lot of people. The train was overcrowded. People even sat on the floor. When we reached one more station, we saw that train that we could not get on – it was totally bombed and destroyed. Our train was also bombed. During the bombings we would run out of the train and lie down on the ground. In Kiev we stopped not at the central station, but in Darnitsa. I went to my sister’s house across the town, at night, in total darkness. When my sister saw me, she passed out – everybody was convinced I was already dead.

Kiev was also bombed. From Kiev, my sister and niece (sister’s husband was at the front) we moved to Konotop, to our parents. We began to get ready to further evacuation. Father sewed big bags. He also bought a pair of horses and a large cart (father could drive horses very well. Back after the civil war he drove to a village to exchange clothes for foods). All our belongings, even old clothes, we put on this cart and moved eastward. Roads were heavily bombed. Two weeks later we reached Voronezh. Only there we got on a train. In the middle of October we reached Pugachevsk, which is behind the Volga River, in Saratov region. It was already cold. We found a small room to rent, but when its landowner heard my parents speaking in Yiddish, she immediately exclaimed, “I don’t want to have any Jews here!” So, we had to look for another place. We settled with a family: a couple with two children, a 14-year-old boy and a 12-year-old girl. Their house was very poor; they had absolutely nothing there. Even in the villages in Ukraine I have never seen such poor families. In Ukrainian villages people at least have trees and flowers around their houses, but here they had nothing. My father found some wooden boards and made us trestle-beds. He could do everything with his own hands. My mother and I slept on a big trestle-bed, while he slept in a smaller one; for my sister and niece we found a real bed somewhere. It was good that we had brought bed sheets with us. But the bad thing was that our neighbors behind the wall quarreled and swore all the time. We never heard such words before. That is why mother sought and found another flat, and in spring we moved to live with a woman, whose husband was killed at the front. I quickly found a job as a bookkeeper at a mill department. Mother and sister did not work. My sister got money for her killed husband (he was killed in the first days of the war; we only got one postcard from him). At the work I was given a small land plot, but the soil there was like rock. My sister, mother and I worked hard on that land. We planted melons, water-melons, and pumpkins. My father sewed things.

When the war broke out, my brother Boris volunteered to go to the front. But at the military enlistment office he was told that specialists like him were needed in the rear. So, he was sent to Kuibyshev. We knew nothing about him. From Pugachevsk, from evacuation, we wrote to every institution we could; we had a whole folder with correspondence. Finally, with great difficulty, we found him. He was working at the aircraft-building plant in Kuibyshev.

Kuibyshev was located 150-200 km away from Pugachevsk. Sister Ida went to see him in Kuibyshev. When she came to his dormitory, none of his friends believed it was his real sister: he had blond hair and blue eyes, just like our mother, while she was a brunette with dark eyes. Due to his appearance, many people thought my brother was Russian. But he never changed his name or patronymic. Kuibyshev was in famine. My brother had to work hard; sometimes he even slept at the plant. They were building the plant and putting out products at the same time. It was very cold, and their hands froze to the metal. Everyone worked for the front back then. They put out armor. My sister met his girlfriend, Katya, whom brother married after the war. But I will tell you later about this.

From Pugachevsk, I was sent to work in Moscow, to the metro-building company. I worked as a bookkeeper. I lived outside Moscow, in a horrible dormitory with rats and no heat. At the same time I studied at the Red Cross courses and worked at a hospital. I felt ill with furunculocis. As soon as Kiev was liberated (November 6, 1943), I began to pursue return to Kiev. It was impossible for the evacuated to simply return to the places they wanted. My parents returned to Konotop in June, 1944, but I was pursuing permission to go back to Kiev. On my way to Kiev I visited parents, and on September 1, 1944 I came to Kiev. I had no problems with finding a job. I began to work as a chief accountant at a small plant. Its director and most of its workers were Jewish. We found that the room my sister used to live in before the war was occupied. A bad man settled there: he did not live in Kiev before the war, but he was a lawyer, and he knew all ways in and out. Then a wonderful law was issued that one could fight for his/her own flat if one had registration in Kiev and a flat. We had all of it because we settled with our far relative Murochka (her husband was repressed in 1937 and died; she was arrested, but returned home). When the court made the decision that our former flat belonged to us, this lawyer made the court terminate its decision; he gave false testimonies and even bribed the court. The chief of the registration office knew us before the war (I even remember his name – Klimov), but he told the court he knew nothing. With great difficulties, through different court institutions, we could finally get back our flat two years later (despite the fact that my sister had every right to have it, because her husband was killed at the front).

Immediately after the end of the war, my brother Boris married that Katya, whom he met in Kuibyshev and about whom my sister Ida told us. He brought Katya to Konotop. Boris was 37 then. Boris and Katya loved each other very much. My mother was certainly very concerned that her daughter-in-law would be Russian, but my father told her not to talk about this. So, mother received them very well. My brother remained to live in Kuibyshev for the rest of his life, together with Katya and his children.

In 1945, when the war was over, I found out that I had no winter coat. My father found some fabric to make coats for me and my sister. It was hard to get vacation at that time, so I went to Konotop on October Revolution holiday. The Vengerov family settled with my parents after the war. And before the war they lived next door to the family of my future husband. They were great friends. My aunt Soreh-Liba nursed my future husband, young Benyumchik. He was treated like their own child. So, on the October Revolution holiday in 1945, Benyamin Gutner had a leave from the military. He came from Germany to see his parents and came to visit my parents and the Vengerovs. He came, wearing a naval uniform. He was happy to see me. We sat and talked for a while. He found out when I was going back to Kiev and said he would be going together with me. Before the war he worked in Kiev and had friends there. He wanted to see these friends and walk the streets of Kiev. He still had time to do that. His mother gave him a whole suitcase of food. So, he took his suitcase and my bag and we got on the train. When we came to Kiev, my sister was happy to see him alive. In the morning I went to work, and in the evening, my sister said that he had asked her whether I would refuse to marry him should he make a proposal.

Benyusik and I went to the theater. In the break he went to the buffet and bought me a bar of chocolate. It cost 100 rubles then! I told him I would not eat it at the theater but at home, together with my sister Ida. It was a rare occasion when somebody could eat chocolate, because it was right after the war.

So, then he mastered up boldness and made me a proposal. He had to serve some more and then he wanted to marry me. I said I was worried about being 29 years old and two years older than he. To this he said that he wanted to have a quiet and good wife. And with that he left. At the same time a client came to my father, a good Jewish guy, who also was interested in me. His father was a hat-maker – “kifner” in Yiddish. But by that time Benyusik had written a letter to my parents. So, I rejected that other guy. Benyusik and I had no correspondence.

We had not no wedding ceremony: we simply had a dinner at my parents’ house and invited close relatives. My aunt, his parents and cousins came. After the wedding we returned to Kiev. Almost immediately after moving to Kiev he became very ill. During the war he had a leg injury. But when he was fighting he forgot all about that wound, and only in Kiev he began to feel sharp pains in his leg. He also had high fever. X-ray could be done only privately. He could not walk – I almost had to carry him. He had to undergo a surgery. He had a surgery in November 1946. His bone was drilled and pus was taken out of it. But after the surgery the wound would not heal. The New Year was close, but he was still in the hospital. My mother came to visit us and suggested that he should go see a very good doctor in Konotop – a close friend of my father. His wound was open till spring and no X-ray showed anything. In April my pregnancy leave began, and we went to Konotop. The city hospital was ruined; they had nothing there, we had to bring bed sheets with us (just like now!). But the main thing was that I trusted the doctor. Another operation was made and the doctors saw that the previous surgeon left a cotton ball in his wound, and he had that cotton ball for six months. Our doctor assured us that on May 1 he would even dance. It all took place in April.

On May 9 we returned to Kiev. And on May 19, 1947, my daughter Sima was born. She was named in honor of my father’s mother. My husband certainly wanted a son, but he was happy to have a daughter too. Our second daughter, Bella, was born four years later. She was named in honor of my husband’s grandmother, Beile. After the birth of my second daughter I did not work for 16 years until my children became more or less independent.

Prior to the war we sensed no anti-Semitism at all, but after the war our children and us felt it all the time – at school and especially in entering university. Sima finished school with honors, and in her written exam in mathematics (in entering the Kiev Polytechnic Institute) she received an excellent mark, but at the next oral exam she was given a poor mark. She was able to enter the correspondence department of the Aviation Institute only a few years later, when she was already working. Bella also had problems with entering university. But even though we had problems with anti-Semitism, I’m sure I would have never endured emigration.

After my father’s death in 1957, we took mother from Konotop to Kiev. First she lived with the sister, then with me. Soreh-Liba died in Kiev too, in 1963. She also moved to live with her children – she had four of them. The youngest, Rakhil, died in 1936 in Kharkov. She had three children. Neither Soreh-Liba nor Rakhil worked outside the house after getting married.

My mother and her brother Shleimka, unlike other relatives, lived for a long time. Mother died in Kiev in 1978 at the age of 93. Shleimka also died being older than 90. His last years he lived in Minsk at his son’s.

My husband was a worker, and most of his life he worked as a plumber at construction objects. He died in Kiev in 1998.

I would like to tell you some more about my brother, Boris. He spent all his life at that plant in Kuibyshev. His and Katya’s elder daughter was born in 1946, but when she was 12 years old she died because of leukemia. Then they had two more children – Alla and Mikhail. Their children never changed their last name or patronymic.

My brother was the chief constructor. But during the Soviet Union’s fight against cosmopolitism, in early 1950-s, a Jew, Gurevich, could not remain the chief constructor. So, the plant’s director made him a teacher in the plants’ technical school and put him in charge of a desigh bureau. Of course, after Stalin’s death he could work better again. But he never shared about the nature of his work. I only know that he spent months in Moscow in business trips.

In 1978, I received tragic news about his death. He died from stomach cancer. It was hard for me to think that I would burry my brother. My children stayed with my mother, while my husband and I went to Kuibyshev. The whole plant expressed great honor to him. The cemetery (this was common town, not Jewish graveyard) was far from the town, and there was a truck covered with carpets (it was in March when it was still cold). But the workers did not put the coffin on the truck – they carried it to the cemetery in turns. They made a great funeral banquet for him. I know that Jews do not do such things, but at that place people did that. The tables of the plant’s canteen were covered, but not everyone could fit in. So again, people took turns. Many people spoke about him, shared how he taught, how he treated students, what a wonderful and honest person he was. In 1985 I went to Kuibyshev to visit Katya and her children. Katya invited me to the plant’s museum, which speaks a lot about Boris. It even has his big portrait. We came to the museum when a tour was held for children. The director of the museum told them how my brother started that plant with the first nail and what difficulties he faced. After the tour, the director invited me to his office and sadly said that he had asked Boris many times to write about himself and the plant, but Boris was a very modest person, so he wrote nothing.

My sister Ida always lives and worked in the Kiev. We with her were very friendly, children grow together. After the death of Boris, in 1989, she with the family emigrated to USA. Regrettably we can communicate on the telephone only and much seldom. I know that beside them there all well.

Praise God, we had a good life. My husbands was working, and on top of his salary he always tried to find some part-time work, for instance, fix something for the neighbors. I went to the sewing courses and after a year of studies I began to sew everything for myself and children. I did not want to pay somebody else to sew for us. When I was sewing, some things I knew exactly, other things I tried to understand. My children also learned sewing from me. Then I bought an electrict sewing machine and began to take orders from other people. It was hard at that time to buy decent clothes at the store, so I sewed for anyone who ordered and never denied help to anyone.

I’m now living with my youngest daughter, Bella. Being old is certainly not a happy thing. I need to buy medicine and food, while my pension is small. I would be in despair if there were no Kiev charity fund “Khesed Avot” that helps us a lot. It helps us not only with foods and medicines, but also with care and warm words to us. I really appreciate them very much.

I do not approve of emigration.

You see, when you come to Israel, you realize that you are a foreigner there. It’s in my nature. When I was leaving Moscow, my friends would beg me to stay, promised to provide a room for me, warned about ruins in my native town where I was going. But I told them, “It’s my home”. When I came to Konotop and walked into the town, the road was full of my tears. I saw that it was mine, my home. Once we wanted to go to Germany, but then I said, “No, I’m not going. I can’t go there. I can’t hear that language. I can’t live there. I’m not going”. My husband agreed with me that it would be better for us to stay home. I know people are moving to America, to Germany. Well, we paid too much for moving to Germany – we paid with rivers of blood. I can’t imagine how Jews can live in Germany, in that situation. The Germans hate us!