Anna Lorencova

Prague

Czech Republic

Interviewer: Pavla Neuner

Date of interview: July 2003

Anna Lorencova is retired but still very active, also in various Jewish associations. She has a lively memory and is a good story teller.

She lives close to the city center in a nicely furnished apartment near the famous Prague Vinohradske Theater.

In the room we are having the interview I see her computer which she learnt to use as well as the Internet.

Anna Lorencova is good-looking and she is also a very nice person.

- Family background

My granddad on my father's side was called Filip Weinstein. He lived in Ceske Budejovice, where there was a large predominantly German speaking Jewish community. He was a commercial traveler, and I think that his mother tongue was German.

We didn't go there very often and I don't know whether they were religious. His first wife, my dad's biological mother, died quite early on, so I only got to know his second wife. She was called Sofie Weinsteinova and was born in 1874. In 1942 she was deported to Terezin 1, where she stayed until the end of the war.

After the war she lived in a Jewish old people's home at the Hagibor 2 grounds in Prague, and we used to visit her there. That is where she died. My granddad died before the war, back in the 1930s. He is buried in the Jewish cemetery in Ceske Budejovice.

My grandmother on my mother's side was called Berta Schulzova; her maiden name was Kohnova. She was born in 1875, probably in Konstantinovy Lazne, where her family lived. I can't remember my granddad. His name was Arnold Schulz; he was born in 1865 and died in 1928 in Palupin.

They lived on an estate in Palupin, which is a village at the end of the Czech-Moravian highlands, about 20 kilometers from Jindrichuv Hradec. The estate was bought in 1884 by my granddad's father, Vilem Schulz.

My grandmother was religious and she often prayed. On Fridays there was always Sabbath dinner with barkhes and they observed the other important holidays, too. Palupin probably didn't offer the best conditions for religious observance, because the Schulzes were the only Jews there.

It was a small village with about forty houses, including a small two-class school and a little church. In the land registry books, all the property owners in the estate were referred to as 'church wardens'. This was the case even when there was a Jewish family living on the estate. My great-granddad, granddad and uncle always supported the church and the adjacent cemetery.

Although my grandmother lived in Palupin after she got married where no-one probably spoke anything else but Czech, she never really learnt the language. When we were children she spoke to us in bad Czech, which we found very funny. Despite this, she enjoyed a great deal of respect from the other villagers.

I don't know how educated she was, but she was certainly a wise woman. She kept a large household and had servants; a large amount of bread was baked and butter was churned every week and there were always lots of chickens in the yard. It was a potato-growing region and, besides the estate, which included land under crop, woods and ponds, there was also a distillery where potatoes were processed.

And there was also a small place for making spirits, wine and fruit juices. There was a small ornamental garden by the house and a large garden a bit further on, where they grew mainly black and red berries for wine-making and so forth.

My dad was called Richard Weinstein. He was born in 1896 in Ceske Budejovice and came from a German-speaking family. At home he spoke German and Czech with my mother, but because my brother and I went to Czech schools, we spoke only Czech at home.

My father studied medicine and worked all his life as a doctor. He was a person with a great sense of humor. A lot of his patients were children; when necessary he would remove their tonsils or polyps and so forth. He was great with them, for he joked around, did magic tricks and knew how to amuse them.

His humor came out mainly when he was with the family and among friends, but otherwise he was quite a withdrawn person. He was not very tall; he had a lot of hair. He was a Jew and felt like he was a Jew. They went to the synagogue on traditional Jewish holidays, but I think that this was mainly in keeping with tradition rather than being religious. My parents got married in 1921 and then moved to the town of Most.

I wouldn't want to say how my dad was as a doctor, but children loved him and he would always have a chat with his adult patients. I can remember two incidents that he used to mention. One of his patients was an elderly gentleman who had lost most of his hearing.

There weren't the facilities in those days and there was little else my dad could do for him. So all he did was to blow through his ears and give them a clean. He then asked him to make an appointment for a checkup so he could see how things were shaping up.

As the gentleman couldn't hear very well, my dad pointed to the calendar to show him when he was supposed to come back. The patient said to him: 'Doctor, my eyes are ok; it's my ears that aren't so good!' Then there was another patient who couldn't hear well and found it so unpleasant that he couldn't hear what was being said around him that it drove him to despair.

My dad turned to him and said: 'How old are you?', and he replied: 'Seventy-five,' and to that my dad said: 'Well, you must have heard enough things by now, it's always the same stuff anyway.' In his old age, my dad, too, couldn't hear very well. He had a hearing aid but he didn't wear it, for he followed his own advice.

My dad worked in the mornings and went home at midday for lunch. He would then lie down for twenty minutes and after that he would go back to the medical office, which was in the house where we lived. After work, it was almost a ritual for him to go to the cafe 'Zum Weissen Ross' [German for 'The White Horse'] where he would meet his Jewish companions.

Whenever I needed something from him, this is where I would go to find him. They met there regularly every workday. My dad was not a member of any political party; I think he was completely apolitical. He read the Prager Tagblatt [Prague German newspaper], as did the majority of the local German-speaking Jews. I can remember very well how he listened to Hitler's speeches on the radio in the 1930s and shouted very rude German insults at him.

My mom was called Gertruda Weinsteinova, nee Schulzova. She was born into a German-speaking family in Palupin in 1904. She graduated from the German lyceum in Jihlava, which was a kind of secondary school for girls. She met my dad in quite an interesting way. Mom was one of five children, four daughters and one son, who was the future owner of the estate.

The daughters had to get married and the most important thing of all was for the future husband to be a Jew. But they lived in a village where there was no chance of meeting any. It was, therefore, the duty of an uncle who had studied agriculture in Ceske Budejovice to bring along Jewish boys to see the sisters in Palupin.

But because they were girls from the estate and no riffraff, the boys had to be graduates or at least young students. That was the way it was. The youngest sister, Marta died single and the eldest and most beautiful aunt, Aninka, found her own husband. The two middle sisters really wanted to marry boys whom their uncle Arnost had brought from Ceske Budejovice to Palupin. Aunt Elsa married a lawyer, Pavel Klein, and my mom married my dad.

Before we were born, my mom helped dad out in the medical office, but later on she was a housewife. Mom came probably from a more religious family than my dad, but she wasn't religious herself. She was different from my dad - more practical, and more sociable, too. Ladies would come round to our place quite regularly to play bridge; they spoke German and they were all Jewish.

We used to have various different guests round, though. But as far as I can remember, the closest friends of my parents were all Jews. My mom occasionally played the piano. I learnt to play the piano with my brother, too, but I didn't stick to it.

My grandparents' only son, Uncle Arnost [Schulz], was born in 1898; he was the second oldest of the siblings. He graduated from an agricultural school in Ceske Budejovice and took charge of the estate after my granddad's death. My grandmother transferred half of the estate over to him and kept the other half.

He married Aunt Vera Hellerova, a Jewess from an estate in Zalesany. They had two daughters, Sonja and Gita. Sonja was born in 1929, survived Terezin and, after the war became an actress. She died at the age of 29.

Gita was born in 1933, also survived Terezin, and immediately after the Soviet occupation and 1968 [see Prague Spring] 3 finally emigrated with her husband and daughter to Germany. She died in Munich in 1992. Aunt Vera also left for Germany to stay with Gita and her family. She died in Munich, just short of her 90th birthday.

Uncle Arnost didn't survive the Holocaust. The Germans seized the estate in 1939 and arrested him. Via the Brno Kounic 4 track he was sent to Auschwitz where he perished in 1941. At that time, his mother, wife and children were still at home in Palupin.

They were deported to Terezin in May 1942. Beforehand, Uncle Arnost had tried to emigrate to Argentina, but that was conditional on him being a Catholic. The whole family had to get baptized in the little church in Palupin. But his attempt of emigration failed. It was too late already.

Many Jewish people got baptized at this time but according to the Protectorate law they were taken still as Jews [also see Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia] 5. My grandmother was transported to Terezin where we met. She didn't work there and was transported later to Auschwitz where she died in 1944 in the gas chamber.

The eldest of the Schulz children was my mom's sister, aunt Anny Pernerova, who was born in 1897. Her husband was an engineer and also, of course, a Jew. Aunt Anny was an extremely beautiful woman. They had two children, Pavel, who was born in 1923, and Kamila, born in 1926.

Kamila, who they also called Mimi and Mimuska, was the cousin I got on best with. Uncle Walter Perner was a manager at some production plant. They used to move house a lot. In the end, they were living in Jihlava, which was probably the first Czech town that was supposed to become 'judenrein' 6, which meant that all the Jews had to move away.

The Perners then came to Prague. I assume that my uncle worked for the Jewish community, because they stayed in Prague for a relatively long period of time. In 1943 they were arrested after being informed on. Uncle Walter and Aunt Anny were sent to the Small Fortress 7 and then to Auschwitz, where they perished in the same year.

In July 1943 Pavel and Kamila were put on a transport to Terezin and in October 1944 were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they both perished. I can't imagine that either of these beautiful young people would not have got through the selection or have been rescued. I think they must have been branded 'RU' - 'Rückkehr unerwünscht' [German for 'return undesirable'].

[Editor's note: The Gestapo used this label, usually for political prisoners. They were sent to the concentration camps and were not supposed to return; it was an indirect death sentence.]

Another daughter of the Schulzes was Aunt Elsa Kleinova, who was born in 1901. Her husband was Pavel Klein, a lawyer. He was always in the center stage whenever people got together, for he was a terrific person and had a great personality. He may have been a good lawyer, but he was what they called a lawyer for the poor, so he didn't get on too well financially.

They lived in Prague. We would sometimes come over from Most and pay them a visit. They had two children, Tomas, who was born in 1928, and Marta, born in 1929. They weren't sent to Terezin until the summer of 1943, seeing that my uncle worked for the Jewish community.

After the war, Marta told me that she envied us for being in Terezin, as it was so terrible in Prague at that time - there was no-one to talk with and they weren't allowed to walk on the sidewalk, in fact they couldn't go anywhere [see Anti-Jewish laws in the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia] 8.

Things were so unpleasant that she was looking forward to being among her own. Once in Terezin Marta spent the whole time lying in the tuberculosis ward, as she had fallen ill. They were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau in December 1943 on the second transport of that month and then stayed in the so-called Czech Family Camp.

After its liquidation in July 1944, they were all subjected to the selection process. Uncle Pavel and Tomas didn't return and we never found out the circumstances of their deaths.

Marta and Elsa were rescued, but it was all very dramatic. They got to the Stutthof 9 camp where they were sent off to work. Together with other women, they dug trenches in the vicinity of Gdansk. It wasn't a proper camp, for they lived in tents and when they finished work in one spot, they just moved on to another.

They survived under wretched conditions. The Red Army liberated them in January 1945, by which time they were in a desperate state, sick and frost-bitten. They received treatment at a military hospital and were then sent on a hospital train to the center of the Soviet Union, where they stayed for a long time in various camps, along with captured Germans [POWs].

Later on, a few of the young girls there were sent home with them, while the others remained incarcerated. Marta returned in November 1945 on her own. Aunt Elsa didn't return until 1946.

After my mom, my grandmother had another daughter, Marta, who was the youngest. She died single; I think it was in 1928. Apart from her, I knew all of mom's siblings and their families quite well, because we used to spend all our vacations together in Palupin.

My brother is called Hanus Hron, and he was born in Teplice in 1925. As a boy he was always inventing and making things, connected with perpetual motion and so forth. He actually made a radio set, known as a crystal receiver - a tiny thing with earphones.

There was a lot of sound interference, but it worked and it gave him a lot of pleasure. After the war he finished his schooling and became an external student at the School of Mining and Smelting in Ostrava. He worked for a long time in the Ostrava area, mainly at the Trinec Iron Works. He now lives in Nejdek; he's retired and has three adult children. He's still as inventive as he has always been. I'm glad to have him as a brother.

- Growing up

At home we were brought up in the conviction that we were Jews. That was paramount. The company my parents kept was completely Jewish. We kept certain traditions, but we were probably not as religious as most other Jews in Most or in the rest of Bohemia. We were assimilated and didn't stand out from other people in terms of our appearance or way of life.

The main holidays were observed and we went to the synagogue, but we didn't have kosher food at home. We also celebrated Christmas, but not as a Christian festival with carols - we just had a Christmas tree, had carp for dinner and gave each other presents. There were always a lot of children from the family who would meet up at my grandmother's house in Palupin.

Often, the children of distant relatives would also turn up there. There were usually at least 10-12 children and at Christmas we always put on some kind of program, performed little dances, sang and recited poems.

My parents fasted on the main holidays [the interviewee is referring to Yom Kippur], but I can't remember if we tried to fast as children, too. On Sabbath my grandmother would light the candles. We didn't celebrate Chanukkah, but I can remember celebrating Pesach. It sometimes overlapped with the school spring holidays, which was when we went to Palupin, where we had a proper seder meal and my brother would ask the mah nishtanah.

As children we took part in Jewish parties during Purim. The Jewish community in Most was led by Rabbi Halberstamm and 'Oberkantor' [German for 'chief cantor'] Mueller. There wasn't a yeshivah or a mikveh there, at least I don't know of any. My parents were, of course, members of the Jewish community.

There was quite a large synagogue in Most; it was burnt down during Kristallnacht 10, but we weren't there when that happened. We didn't go to the synagogue only on the main holidays, but also on the less important ones. It was actually a social occasion.

Although my father was a doctor, we weren't very rich in any way. The house in which we lived in Most was probably acquired from my mom's dowry. It was an old house, but it was in the town. On the first floor was the medical office, waiting room and sitting area, because my dad had outpatients and did minor operations, such as removing tonsils.

Also on the first floor was an apartment for the janitor, who was employed by us. Opposite our house was a theater, behind which was a beautiful park that we used to stroll through. The town of Most had a population of about 30,000. It wasn't exactly a pretty town, as it was full of opencast mines and the air was always full of dust.

When we were coming home from our vacation in Palupin, we could feel the dust in the air by the time we reached Bilina. And whenever it got foggy in Most, you couldn't see through it at all because of all the fly ash. My dad moved there probably because there wasn't an ear- nose-and-throat specialist, and he was looking for a place where he could come in useful. We lived on the second floor in a four-bedroom apartment.

We had a dog, an Airedale Terrier, called Bobik. We paid for him dearly, because he was always running out of the house and straight on to the road and he took delight in jumping up at cyclists. From time to time, my parents would have to pay for the cost of trousers that had been torn and other such damage. Our dog slept in the entrance hall. My dad took him for walks every day and I went with them very often.

The apartment had a dining room, a lounge for guests, a master bedroom, a children's room and a kitchen. In the dining room there was a large table with a tapestry that my mom had sewn herself. In the corner was a large tile stove. The dining room was efficiently furnished and was connected with the kitchen.

Cooking was done on a traditional coal-fired range. We didn't have two sets of dishes. In the bathroom was a bath stove, which had to be fired up for there to be hot water. In the lounge was a so-called American slow-burning stove, which was very modern in those days. It was a low cast-iron stove with small windows covered with mica plate in the doors, so you could see the flame. It was heated with anthracite, which apparently was the most expensive fuel as it was processed from coal.

It really was slow-burning, because if it was turned on at the beginning of the winter, it would stay on until the spring. In addition, there was a round conference table with armchairs and a bookcase, which consisted mostly of German books. There was also a grand piano. The floor was carpeted.

In the lounge were three doors which led to the dining room, bedroom and entrance hall. In the children's room I can remember there was a cabinet under the window where we kept our toys. In the doorway that led from the bedroom was a wooden swing that was suspended on hooks.

There was parquet flooring throughout the apartment, except in our room which had linoleum. It was real drudgery cleaning the parquet; mom spent a lot of time on her hands and knees there, even though we had a maid, Mrs. Mana. They scrubbed the floor with special wire and soapy water, which had to be rinsed loads of times and took ages to dry. After all that, they polished the floors with a hard brush.

In Most we always had lunch and dinner together at home. On Sundays I would go with dad to a special candy store for delicious meringue, which we usually had after Sunday lunch. In our house we had to eat everything there was, for the general rule was that what didn't get eaten for lunch was served up for dinner.

I didn't like cumin soup, but I always ate a little bit of it, just to show willingness. The food we had was rather stereotypical. Very often it was beef, vegetables and potatoes - and beef soup. We also had cumin soup quite often, usually with meatless lunches. We ate very little pork at home; we had a lot more of it in Palupin, where pigs were actually bred. There were days when we had pancakes or potato goulash. I can also remember my favorite, stuffed peppers, beans in a creamy sauce, and lungs.

For our vacations we went to Palupin, which has a superb landscape - gently rolling hills, beautiful woods and lots of ponds. Uncle Arnost was involved with rearing pigs, which he brought in from England. They were special pigs that had little fat on them and lots of meat. On the estate there was a large amount of cows and several pairs of horses.

Uncle Arnost rode horses and had one or two riding horses. We usually got together in Palupin during the vacations; when all eight of grandmother's grandchildren got together, we were quite a large group. The estate was pretty spacious, so when we all met up there, there was room enough for us all. There was also a bathroom with bath stoves.

In Most I attended a splendid new elementary school, the Masaryk School for Girls, which was about a fifteen-minute walk from where we lived. I enjoyed school and I found it easy on the whole, except for handiwork and composition and exercises.

Apart from poems, we didn't have anything at all to learn at home. I think that it was easy for the other children, too. I had a lot of non-Jewish friends. In our class there were only two Jews, me and Alice Kohnova, who lived on the outskirts of town and wasn't one of my friends.

My main friends were Vera Ottova, whose parents had a candy store, and Jarmila Borovcova, whose dad was the manager of an insurance company, I think, and Vera Gregrova, who lived near me and who I sometimes walked to school with.

I wasn't aware of any signs of anti-Semitism at school, but there was certainly tension in Most between Czechs and Germans. Lessons were held only in the morning; in the afternoon there was only religious education. I took piano lessons and enjoyed singing.

I read various novels for girls, as well as my brother's books. We subscribed to the children's magazines Mlady hlasatel [Young Announcer] and Srdicko [Little Heart]. I went to the Scouts [see Czech Scout Movement] 11 and exercised at the Maccabi 12 and at Sokol 13 sports grounds, although I don't know if it was at the same time.

I never joined a Zionist organization. When we came to Prague and we didn't know anybody, I somehow turned up at a Zionist group meeting; perhaps my parents sent me there. I was only there once or twice; they were singing Hebrew songs that I didn't know, and it all seemed strange to me. In Prague, of course, we went to Hagibor, because we couldn't actually go anywhere else. From September 1941 we had to have the Star of David on our clothes.

In Most my brother attended the Comenius Elementary School for Boys, which was quite near where we lived. The high school was coeducational. I went there for about a week, in September 1938. That was just before the occupation of the Sudetenland 14. We were sent to stay with our grandmother in Palupin.

No-one knew how long it would be for, so at first we both went to the two-class school in Palupin, but we didn't belong there at all. That was just for a few days, before it was decided where to go next. We then went to the nearest community, Strmilov, where there was a council school.

We went to school by bike, but we only had one, so my brother would ride while I was sitting on the crossbar. On the way back I had to walk. For one thing, we didn't have lessons together, for the other, it was uphill almost all the way home, so the bike had to be pushed.

In the meantime, my parents had moved from Most to Prague, where we came to stay with them at the beginning of 1939. In Prague we didn't move up to the high school, but we both went to the council school. My brother later started an apprenticeship at the CKD factory [Czech-Moravian Kolben Danek, engineering company], but he wasn't allowed to complete it.

In the school year 1940-41, we were not allowed to attend school [see Exclusion of Jews from schools in the Protectorate] 15, so I completed the third grade at the Jewish school on Jachymova Street. There were excellent teachers there and the standard was high; I liked the Czech teacher Jirina Pickova the best. I didn't get to the fourth grade though.

The two third grades moved up to a single fourth grade, which was terribly overcrowded. In the fall of 1941 I joined a Jewish group, but I didn't stay long because we were deported in December 1941.

I can't recall any concrete manifestation of anti-Semitism in Most. I think that the people around my parents were apolitical. Although they came from German orientated families, my parents respected President Masaryk 16 because he had established the republic and Jews were grateful to him for fighting against anti-Semitism.

My dad employed a German nurse in his medical office, which shows that before Henlein 17 came on the scene, there was by no means any major animosity around. The nurse liked us, but all of a sudden she became a Nazi. I can't actually remember when, all I know is that it was talked about. But I think that she was at my dad's office until the time we left.

- During the war

As I mentioned earlier, my dad was an apolitical person, but he had some kind of 'Jewish radar' and when Petschek, in 1938, began to sell his mines in northern Bohemia, my dad decided that we should move away. [Petschek, Ignatz (1857-1934): German industrialist with considerable influence on the Czechoslovak economy.]

After the Munich Pact 18, when Germans occupied the border regions, we moved to Prague, where we lived in a small apartment on Hermanova Street. Dad was trying to arrange for us to emigrate to America. On the same street, a bit further down, on the second floor in a normal residential apartment, was a Jewish prayer hall where we would go sometimes.

As children, we didn't find all the anti-Jewish measures and restrictions as difficult as adults did, for we just adapted to things. When we were no longer allowed to travel by tram, we went to the Hagibor sports grounds by foot, although it was pretty far from where we were living.

My dad was no longer looking for employment in Prague. He was doing what he could to be able to emigrate to America, but it didn't work out for him. It was extremely difficult, for it required a lot of money, we weren't from the area and he didn't know anyone here.

Dad wasn't familiar with the local conditions and probably didn't have the right nature for this kind of thing, as he was actually a shy person. In short, our family didn't manage to emigrate. In the end, there were some people, perhaps acquaintances, who left for America. America required an affidavit, which meant some kind of surety.

Either you had to deposit a certain amount of money somewhere, or somebody had to accept liability for you. We didn't have anyone in America to help us, so our parents gave the relevant people nearly all their savings so that they would put down an affidavit for us.

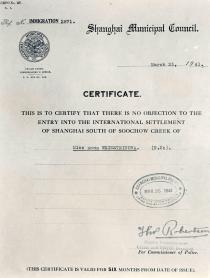

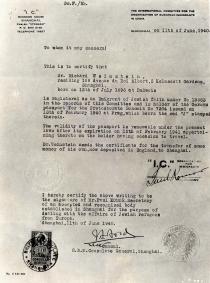

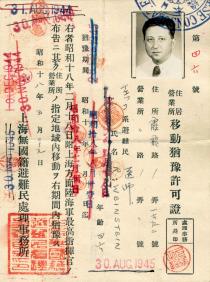

And those people then sent word that they had lost the money. After that, there was no money and no possibilities left. Only Shanghai was still an option for Jewish immigrants. Dad managed to get there, traveling by train across the Soviet Union.

It took several months before he could arrange the necessary permits for us. He sent each of us the appropriate document, but by the time we got it, we weren't able to leave. In Shanghai my dad worked as a doctor.

When we came from Most to Prague, we moved into a new house that had been built in 1938 for employees of the National Bank. It was an entire housing block on Letna Plain [large plain in Prague, popular place for summer walks]; building work was still going on around it, but three houses were already standing.

Our house had a wide marble staircase, the apartments had modern facilities with electric cookers, the cellar had a modern laundry room with a washing machine, spin-drier and a drying area, and we had district heating. The house was situated in an area where a lot of Germans were living. Because it was a very nice house, Germans often came round to look at our apartment. That could have been the reason why we were summoned for deportation as early as 1941.

This is corroborated by the fact that when we returned, the apartment was empty, as German tenants had just moved out of it. In the summons to transport it was stated what we must, and what we must not, bring with us. Other families that went later were usually prepared, but we weren't.

My dad was no longer there and mom had decided not to leave our beautiful furniture for the Germans, so she swapped it for some old junk that belonged to another family in the house. She hid her jewelry and other items where various acquaintances were living and gave the janitor's family several suitcases, mostly full of clothes. When we returned, the janitor was no longer alive; he had been murdered by a German two days before the end of the war. He now has a small memorial plaque in the street.

The assembly point was in wooden buildings on the Trade Fair grounds near what is now the Park Hotel. It was just a short distance from our apartment, so we went there on foot. Various administrative operations and thefts were still under way at the assembly point. Identity cards, money and jewels, if people had any left, were handed over.

Out of fear, and out of defiance, people threw money down into the latrines. I think that house keys were also handed over and people had to sign various declarations legalizing all the robbery that was going on. For quite some time our accounts had been blocked, which meant that we could withdraw only a very limited amount of money.

We spent almost three days and, I think, two nights at the assembly point. Early in the morning, probably about 4am, we were taken to Bubenec Station, from where we left on passenger trains to Bohusovice. When we were seated in our compartment, an SS man appeared and called out our names.

We had to stand up, but the benches were so crammed that we could hardly squeeze our way out. The uniformed German then handed over a letter that my dad had sent mom. In Bohusovice the 'Transportdienst' [transport service] was already in waiting; young Jewish guys loaded the heavy luggage onto carts and we went on with only one bag each.

We were taken away to a 'Schleuse' [German, literally 'sluice'], which was a kind of sorting center. We were registered again here and then assigned to billets, the latter falling within the scope of the Terezin Jewish self- government.

At first we lived with mom in the Podmokly barracks, but after a short while we were moved to the Hamburg Barracks. At that time, in December 1941, Terezin was still inhabited by Czechs; not everything had been cleared out yet and people lived only in the barracks.

My mom volunteered as a nurse, so I lived with her in the nurses' room. It was pleasant there because we were living with mostly young, clean and refined women - all of them nurses. They had various shifts, so there was always someone to talk with. I was the only one who had no work to do, but I still enjoyed myself enough, being among the nurses.

They spoke about all kinds of things that I was very interested in, and they secretly smoked. Some of them were really strong smokers and they would swap cigarettes for food rations. I can well remember one of them in particular. She was called Hanka and was about 18 years old. She smoked so much that she exchanged a large proportion of her food for cigarettes and, as a result, was always hungry.

The nurses occasionally had an obligation - although it was perhaps to their benefit - to work in the fields; they would pick flowers, grass or ears of corn and use them later to decorate their corner of the room. I can remember one day when Hanka was sitting on a table, dangling her legs and she asked the other nurses: 'Do you think you can eat flowers?' 'Why not, after all, cows eat them and they live.'

But basically I didn't have anything to do and I was bored. A girl I had been friendly with came on the same transport as me. She was also called Hanka and she lived with her mom in the same barracks. We would often stroll together through the long corridors of the barracks or through the courtyard, thinking up ways of amusing ourselves.

Fortunately, sometime in the spring of 1942, the Jewish self-government set up a separate room in the barracks for girls, which was where we moved in to. We had a great supervisor, Kamila Rosenbaumova, who was a dancer. She rehearsed a program of recitation and dance with us, which was based on Nezval's poem 'Znam zemi blizko polu, znam divukrasnou zem...' [I know a country near the pole, I know an exquisite country]. [Nezval Vitezslav (1900-1958): Czech poet, dramatist and translator.]

The poem was in praise of the Soviet Union, and we recited it as a chorus or in combination with solo acts, and it had a kind of simple melody, a bit like a 'voiceband'. And as she was a dancer, she had shown us various movements to perform.

At that time, we also started to do work in the garden, the so-called 'Jugendgarten' [German for 'garden for youth']. It was a great achievement and the Jewish self-government did a lot for children by employing them. They no longer felt bored; instead they felt useful, they could be outside and, from time to time, they could nibble at vegetables when they were ready for picking.

By 1942 all the original inhabitants of Terezin had been moved out and the entire town had opened up. Jews moved in and occupied all the houses, and the transports kept coming. At that time, young peoples' homes were also being set up. The girls' home 'L 410' was situated next to the church. It was a three-story building, and the girls were put in separate rooms according to their age. We older children went to work during the day and when we got back we were attended to by a tutor. At first I was in room 29, where the tutor was Rozi Schulhofova. Plenty of interesting people, including professors, writers and musicians came to see us to give talks or to discuss different topics.

My brother lived in the Sudeten Barracks with the men. At first we weren't at all allowed to go there since we couldn't leave our barracks without a pass. After a certain period of time, it was arranged that girls under 14 could go to the men's barracks once a fortnight, provided they were accompanied, so as to see their dads.

I was 14 and actually didn't belong to that group, but my mom somehow always managed to push me through, so I was able to see my brother. Now and again, I would bring him the odd button and such like or I would stroll around the courtyard with my friend Jirka.

My brother was very skilled with his hands, so from the outset he was employed in the locksmiths' workshop. In 1944 he volunteered to join a group of artisans who were sent to do work in Wulkow, which was about 30 kilometers from Berlin.

They were to build timber buildings for the 'Reichsicherheitshauptamt' or RSHA - the Reich Security Head Office - which were intended for the RSHA archives and also for the Germans who were supposed to work there. The deportation list to the extermination camps was drawn up by the Jewish self-government. Because it was routine policy at Terezin not to split up families, my brother actually saved us from deportation throughout the time he was away.

The group returned to Terezin in the spring of 1945. We had been put on the deportation list at the beginning of 1942, which was when I was still living with mom in the Hamburg Barracks. Anyway, my mom put me to bed - actually we still slept on the floor back then - and somehow she arranged for a doctor she knew to say that I had scarlet fever, so we were crossed off the list.

None of the people on those transports ever returned. Later on, I was put on another deportation list, but I think that was when my brother was in Wulkow, so I was crossed off the list again.

In 1943 there was a typhoid epidemic in Terezin, which struck me too. It spread very quickly and an infection ward for those infected with typhoid was set up in the Vrchlabi barracks. They were long barracks rooms and because there were four or five girls between the ages of 15 and 16, we were put next to each other.

We were there for quite a long time, with severe diarrhea and, at the outset, in a state of semi-unconsciousness. When we finally got up, we were unable to walk. On my left was Ruzenka Voglova, with whom I established a friendship that has lasted to this day, even though Ruzenka lives in Israel.

When they let us out, we returned to house 'L410' and were put in a convalescence room, instead of being with the other girls. I then moved out with Ruzenka, and we stayed together until the fall of 1944, when she was sent to Auschwitz.

Apart from her and her grandmother, who stayed in Terezin, none of her family survived. After the war she lived with her grandmother in Zatec; at that time, we were hardly ever in touch with each other. In 1948 she left for Israel. But she has an apartment in Prague and she comes here regularly.

- Post-War

My husband was called Bohumil Lorenc, and he was born in Moscow in 1925. We met at the [Czechoslovak] Youth Association 19. He wasn't an educated person, but was extraordinarily intelligent and handsome. We got divorced.

I have two daughters, Lenka, who was born in 1951, and Eva, born in 1954. Lenka is a nurse, and she is married and has a son and daughter. Eva is an editor for a publishing house and has three sons, the youngest being 16. They both live in Prague.

We often see each other and we celebrate birthdays, Christmas and other occasions together. They weren't brought up in a religious way, but most of my friends are Jews and my children grew up together with their children and are still friends with some of them.

They were both known as 'Maisel Children' [named after Maisel Street where the Prague Jewish community is situated] in the 1960s, when the regime gave way a bit and allowed them to meet at the Jewish community center. Various talks and parties were held there. It was a strong bond and although many of them emigrated, they occasionally come from all over the world to meet up.

I myself didn't think about emigrating after the war. Instead, I joined the Communist Party [of Czechoslovakia] 20, as I believed in its attractive theories. In communism I saw a solution to the Jewish question. Even before the war I was inclined towards communism, for there was a kind of omnipresent salon communism about, especially in literature and the humor of Voskovec and Werich 21.

After all, even the son of one of the proprietors of the Brouk and Babka retail chain [commercial firm in Prague, later with branches in Ceske Budejovice, Ostrava, Brno, Pilsen and Bratislava] was a communist supporter. It was all in the air. I would have rather joined the party in Terezin, but communists had to conceal their identity back then. So I joined after the war - not straight away, surprisingly, but in 1946.

It was certainly disillusioning to see all the different kinds of collaborators as they brought out the flags and started to chant out the slogans. At that time, the Communist Party hadn't yet made its presence so visible. In the first postwar years there was still a relative degree of democracy; the Soviet army was here, but there was still a democratic government. However, the Communist Party already had quite a lot of power and support.

When the political show trials of Jews began in the 1950s [see Slansky trial] 22, however, we found out what it was all about. But I still couldn't drag myself out of it. They already knew that I didn't belong to the Party and we already knew that we didn't belong there, but we didn't find the courage to get out of it, so we thought that things should be resolved from within.

That is my own life sentence. It is a fact, though, that a young person who knew nothing and had no experience of life and had experienced World War II as a Jew, would have found it hard to resist the lovely idea of freedom for all people. And it took quite a long time before I understood that there was a fundamental difference between what was said and the way things were.

So I stayed in the Party until they threw me out, which happened in 1968/69, as part of the vetting proceedings at the Czechoslovak Radio [see Political changes in 1969] 23. But by then I had been going the completely opposite way for a long time. I once heard a story about a professor at the Faculty of Philosopy in 1948 who went out through the door and jumped in the air three times.

When asked what was going on, he said: 'They've just thrown me out of the Communist Party.' I did exactly the same thing, when I was thrown out - I jumped in the air three times.

I didn't experience any explicit anti-Semitism from any specific people after the war. Anti-Semitism over here was mainly linked to the state; I was dismissed from several jobs, for instance. The first time I got the sack I was still a 'faithful' communist, that was just after the coup of 1948 [see February 1948] 24.

I was working at the Secretariat of the Youth Association, but it was because of my bourgeois origin that they got rid of me. At that time they dismissed my brother and many of my Jewish friends from their jobs. A lot of Jews lost their jobs after 1948.

I had various jobs. After the war I made a big mistake in not going to a normal secondary school, but instead attending the photography department of a school of graphic art. I was employed as a photographer with the Skoda Company 25 for a while, and then for the afore-mentioned Youth Association, from where I was fortunately dismissed. At the beginning of the 1950s I worked at the City Library and then at an educational institution and at the Prague Information Service.

In the meantime I was an external student and, in May 1968, I entered and won a competition for a position at the study department at the Czechoslovak Radio. As I was in the process of finishing school and was about to take my final exams, however, I wasn't able to take up the post until July.

Then came the Soviet Occupation in August [see Warsaw Pact Occupation of Czechoslovakia] 26 and after that I got the sack. I was then taken on by the then Jewish State Museum, at a time when Dr. Vilem Benda was director. He was very kind, for he took on four people who had been fired from other jobs.

The exceptional and strange thing was that he took us on at a time when all cultural institutions had already been 'purged', normalized and given new directors. At the museum, the original director was allowed to stay on for a long time, which was why we got in there. In the end they got rid of him anyway and along came a new director by the name of Klima who thoroughly 'purged' the place.

At the beginning of 1974 I was taken on as a bookkeeper at the Housing Cooperative. I had never done bookkeeping before and had never learnt it properly, so they then gave the job to someone else and I became a secretary at the cooperative, which meant that I was a girl Friday, but I enjoyed it and I stayed there for almost twenty years.

We followed what was going on in Israel all the time. Some of my relatives went there after 1948, some just before the war, and many of my friends have emigrated there. I corresponded with my cousin Marta and friend Ruzenka for all those years. I didn't consider emigrating.

I thought about it a bit in 1968 but my daughters didn't want to go and we probably wouldn't have had enough money for it anyway. I've been to Israel many times, the first time being in 1969. The rest of the visits were after 1989.

I wrote various things and distributed Samizdat literature 27, helped out in the [Czech] Helsinki Committee 28, and so forth. As a family we were definitely persecuted by the regime. I was given the sack, my daughter Eva didn't get a university place in Prague; in the end she was taken on as an external student [not attending courses every day, only a few times a month.] in Brno.

A strange thing happened to me when I was working at the cooperative. The then chairman took me on when I had to leave the Jewish Museum, and he knew that I was a Jew. A Jewish woman had already been employed there before me.

When men from the StB 29 came to take away the typewriters I had been using for Samizdat, for a so-called mechanical examination, they paid him a visit and told him that I should be fired. But he stood his ground and said that he wouldn't do it. He then came over to tell me everything that had been said. It was a remarkably brave and rare thing to do.

In 1984 my dad died in Ceska Lipa, where he had been working as a doctor. My mom and dad got a divorce after the war. He didn't get remarried, but he lived in a very beautiful relationship with his companion, Maruska. My mom married again and worked all her life as a nurse; she even worked at the hospital after retiring. She died in Prague in 1988. I'm sorry that she didn't live to see the revolution.

We welcomed the revolution of 1989 [see Velvet Revolution] 30 with enthusiasm. My children went on all the demonstrations and even with toddlers on their shoulders. My entire life was changed by the revolution. The only thing I regret about the past is that our very many social contacts have disappeared.

In the past, we all did menial work but we had plenty of time for each other. Since the revolution everyone has got involved in different projects or tried to catch up on things, but all those wonderful social contacts have been broken off.

The Palupin estate was put under state control by the communists in 1948 and about seven to eight different owners alternated there with varied focuses of interest, from breeding ducks to breeding bulls. In the last 17 years prior to the restitution, it was known as JZD Strmilov Collective Farm. I went there with my children on vacation for all those years; we rented a cottage and one time the local authority even rented us three rooms in our own house.

My brother's family also used to go there. When my children grew up, my younger daughter wanted nothing better than to buy a cottage in Palupin, and when that didn't work out, they got one in the next village, which is about a kilometer away.

Very soon after the revolution we got our estate back as part of the restitution. It was in a very poor state of repair. We are trying to look after it, but it is very difficult. But at least our family can once again spend their vacations and weekends over there.

- Glossaries

1 Terezin/Theresienstadt

A ghetto in the Czech Republic, run by the SS. Jews were transferred from there to various extermination camps. It was used to camouflage the extermination of European Jews by the Nazis, who presented Theresienstadt as a 'model Jewish settlement'.Czech gendarmes served as ghetto guards, and with their help the Jews were able to maintain contact with the outside world. Although education was prohibited, regular classes were held, clandestinely. Thanks to the large number of artists, writers, and scholars in the ghetto, there was an intensive program of cultural activities.

At the end of 1943, when word spread of what was happening in the Nazi camps, the Germans decided to allow an International Red Cross investigation committee to visit Theresienstadt. In preparation, more prisoners were deported to Auschwitz, in order to reduce congestion in the ghetto. Dummy stores, a cafe, a bank, kindergartens, a school, and flower gardens were put up to deceive the committee.

2 Hagibor

Prague camp, located on Schwerinova Street. Most of the people interned here were Jews from outside Prague living in mixed marriages. The internees who were fit to work were employed in the 'mica works' of the firm Glimmer-Spalterei, G.M.b.H.On 30th January 1945, it was decided to deport the entire mica works to Terezin. The number of Jews interned at Hagibor subsequently dropped from an average of 1,400 to a mere 100-150. In total, 3,000 people passed through the camp. Hagibor was allegedly closed down on 5th May 1945, and the remaining internees returned to their homes.

3 Prague Spring

The term Prague Spring designates the liberalization period in communist-ruled Czechoslovakia between 1967-1969.In 1967 Alexander Dubcek became the head of the Czech Communist Party and promoted ideas of 'socialism with a human face', i.e. with more personal freedom and freedom of the press, and the rehabilitation of victims of Stalinism.

In August 1968 Soviet troops, along with contingents from Poland, East Germany, Hungary and Bulgaria, occupied Prague and put an end to the reforms.

4 Kounic Hall in Brno

Built as a student residence hall in 1925, the Kounic Hall was converted into a prison by the Gestapo in 1940.It also functioned as an assembly point for deportations from Brno to concentration camps. Over 1,350 people were executed in Kounic Hall after 1941. By the time of the liberation of Czechoslovakia (May 1945), up to 35,000 people had been incarcerated there.

In 1978 the hall was declared a national cultural monument.

5 Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

Bohemia and Moravia were occupied by the Germans and transformed into a German Protectorate in March 1939, after Slovakia declared its independence. The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was placed under the supervision of the Reich protector, Konstantin von Neurath.The Gestapo assumed police authority. Jews were dismissed from civil service and placed in an extralegal position. In the fall of 1941, the Reich adopted a more radical policy in the Protectorate. The Gestapo became very active in arrests and executions. The deportation of Jews to concentration camps was organized, and Terezin/Theresienstadt was turned into a ghetto for Jewish families.

During the existence of the Protectorate the Jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia was virtually annihilated. After World War II the pre-1938 boundaries were restored, and most of the German-speaking population was expelled.

6 Judenfrei (Judenrein)

German for 'free (purified) of Jews'. The term created by the Nazis in Germany in connection with the plan entitled 'the Final Solution to the Jewish Question', the aim of which was defined as 'the creation of a Europe free of Jews'.The term 'Judenrein'/'Judenfrei' in Nazi terminology referred to the extermination of the Jews and described an area (a town or a region), from which the entire Jewish population had been deported to extermination camps or forced labor camps. The term was, particularly in occupied Poland, an established part of the official and unofficial Nazi language.

7 Small Fortress (Mala pevnost) in Theresienstadt

An infamous prison, used by two totalitarian regimes: Nazi Germany and communist Czechoslovakia. It was built in the 18th century as a part of a fortification system and almost from the beginning it was used as a prison.In 1940 the Gestapo took it over and kept mostly political prisoners there: members of various resistance movements. Approximately 32,000 detenees were kept in Small Fortress during the Nazi occupation. Communist Czechoslovakia continued using it as a political prision; after 1945 German civilians were confined there before they were expelled from the country.

8 Anti-Jewish laws in the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia

After the Germans occupied Bohemia and Moravia, anti-Jewish legislation was gradually introduced. Jews were not allowed to enter public places, such as parks, theatres, cinemas, libraries, swimming pools, etc.They were excluded from all kinds of professional associations and could not be civil servants. They were not allowed to attend German or Czech schools, and later private lessons were forbidden, too. They were not allowed to leave their houses after 8pm. Their shopping hours were limited to 3 to 5pm.

They were only allowed to travel in special sections of public transportation. They had their telephones and radios confiscated. They were not allowed to change their place of residence without permission. In 1941 they were ordered to wear the yellow badge.

9 Stutthof (Pol

Sztutowo): German concentration camp 36 km east of Gdansk. The Germans also created a series of satellite camps in the vicinity: Stolp, Heiligenbeil, Gerdauen, Jesau, Schippenbeil, Seerappen, Praust, Burggraben, Thorn and Elbing.The Stutthof camp operated from 2nd September 1939 until 9th May 1945. The first group of prisoners (several hundred people) were Jews from Gdansk. Until 1943 small groups of Jews from Warsaw, Bialystok and other places were sent there.

In early 1944 some 20,000 Auschwitz survivors were relocated to Stutthof. In spring 1944 the camp was extended significantly and was made into a death camp; subsequent transports comprised groups of Jews from Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary and Lodz in Poland.

Towards the end of 1944 around 12,000 prisoners were taken from Stutthof to camps in Germany - Dachau, Buchenwald, Neuengamme and Flossenburg. In January 1945 the evacuation of Stutthof and its satellite camps began.

In that period some 29,000 prisoners passed through the camp (including 26,000 women), 26,000 of whom died during the evacuation. Of the 52,000 or so people who were taken to Stutthof and its satellites, around 3,000 survived.

10 Kristallnacht

Nazi anti-Jewish outrage on the night of 10th November 1938. It was officially provoked by the assassination of Ernst vom Rath, third secretary of the German embassy in Paris two days earlier by a Polish Jew named Herschel Grynszpan.Following the Germans' engineered atmosphere of tension, widespread attacks on Jews, Jewish property and synagogues took place throughout Germany and Austria. Shops were destroyed, warehouses, dwellings and synagogues were set on fire or otherwise destroyed. Many windows were broken and the action therefore became known as Kristallnacht (crystal night).

At least 30,000 Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps in Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald and Dachau. Though the German government attempted to present it as a spontaneous protest and punishment on the part of the Aryan, i.e. non-Jewish population, it was, in fact, carried out by order of the Nazi leaders.

11 Czech Scout Movement

The first Czech scout group was founded in 1911.In 1919 a number of separate scout organizations fused to form the Junak Association, into which all scout organizations of the Czechoslovak Republic were merged in 1938. In 1940 the movement was liquidated by a decree of the State Secretary.

After WWII the movement revived briefly until it was finally dissolved in 1950. The Junak Association emerged again in 1968 and was liquidated in 1970. It was reestablished after the Velvet Revolution of 1989.

12 Maccabi World Union

International Jewish sports organization whose origins go back to the end of the 19th century. A growing number of young Eastern European Jews involved in Zionism felt that one essential prerequisite of the establishment of a national home in Palestine was the improvement of the physical condition and training of ghetto youth. In order to achieve this, gymnastics clubs were founded in many Eastern and Central European countries, which later came to be called Maccabi.The movement soon spread to more countries in Europe and to Palestine. The World Maccabi Union was formed in 1921. In less than two decades its membership was estimated at 200,000 with branches located in most countries of Europe and in Palestine, Australia, South America, South Africa, etc.

13 Sokol

One of the best-known Czech sports organizations. It was founded in 1862 as the first physical educational organization in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Besides regular training of all age groups, units organized sports competitions, colorful gymnastics rallies, cultural events including drama, literature and music, excursions and youth camps.Although its main goal had always been the promotion of national health and sports, Sokol also played a key role in the national resistance to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Nazi occupation and the communist regime. Sokol flourished between the two World Wars; its membership grew to over a million.

Important statesmen, including the first two presidents of interwar Czechoslovakia, Tomas Masaryk and Edvard Benes, were members of Sokol. Sokol was banned three times: during World War I, during the Nazi occupation and finally by the communists after 1948, but branches of the organization continued to exist abroad. Sokol was restored in 1990.

14 Sudetenland

Highly industrialized north-west frontier region that was transferred from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the new state of Czechoslovakia in 1919. Together with the land a German-speaking minority of 3 million people was annexed, which became a constant source of tension both between the states of Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia, and within Czechoslovakia.In 1935 a nazi-type party, the Sudeten German Party financed by the German government, was set up. Following the Munich Agreement in 1938 German troops occupied the Sudetenland. In 1945 Czechoslovakia regained the territory and pogroms started against the German and Hungarian minority. The Potsdam Agreement authorized Czechoslovakia to expel the entire German and Hungarian minority from the country.

15 Exclusion of Jews from schools in the Protectorate

The Ministry of Education of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia sent round a ministerial decree in 1940, which stated that from school year 1940/41 Jewish pupils were not allowed to visit Czech public and private schools and those who were already in school should be excluded. After 1942 Jews were not allowed to visit Jewish schools or courses organized by the Jewish communities either.16 Masaryk, Tomas Garrigue (1850-1937)

Czechoslovak political leader and philosopher and chief founder of the First Czechoslovak Republic. He founded the Czech People's Party in 1900, which strove for Czech independence within the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, for the protection of minorities and the unity of Czechs and Slovaks.After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1918, Masaryk became the first president of Czechoslovakia. He was reelected in 1920, 1927, and 1934. Among the first acts of his government was an extensive land reform.

He steered a moderate course on such sensitive issues as the status of minorities, especially the Slovaks and Germans, and the relations between the church and the state. Masaryk resigned in 1935 and Edvard Benes, his former foreign minister, succeeded him.

17 Henlein, Konrad (1898-1945)

From the year 1933, when Adolf Hitler took power in Germany, the situation in the Czech border regions began to change. Hitler decided to disintegrate Czechoslovakia from within, and to this end began to exploit the German minority in the border regions, and the People's Movement in Slovakia. His political agent in the Czech border regions became Konrad Henlein, a PE teacher from the town of As.During a speech in Karlovy Vary on 24th April 1938, Henlein demanded the abandonment of Czechoslovak foreign policy, such as alliance agreements with France and the USSR; compensation for injustices towards Germans since the year 1918; the abandonment of Palacky's ideology of Czech history.

The formation of a German territory out of Czech border counties, and finally, the identification with the German (Hitler's) world view, that is, with Nazism. Two German political parties were extant in Czechoslovakia: the DNSAP and the DNP. Due to their subversive activities against the Czechoslovak Republic, both of these parties were officially dissolved in 1933.

Subsequently on 3rd October 1933, Konrad Henlein issued a call to Sudeten Germans for a unified Sudeten German national front, SHP. The new party thus joined the two former parties under one name. Before the parliamentary elections in 1935 the party's name was changed to SDP. In the elections, Henlein's party finished as the strongest political party in the Czechoslovak Republic.

On 18th September 1938, Henlein issued his first order of resistance, regarding the formation of a Sudeten German "Freikorps", a military corps of freedom fighters, which was the cause of the culmination of unrest among Sudeten Germans.

The order could be interpreted as a direct call for rebellion against the Czechoslovak Republic. Henlein was captured by the Americans at the end of WWII. He committed suicide in an American POW camp in Pilsen on 10th May 1945.

18 Munich Pact

Signed by Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and France in 1938, it allowed Germany to immediately occupy the Sudetenland (the border region of Czechoslovakia inhabited by a German minority). The representatives of the Czechoslovak government were not invited to the Munich conference.Hungary and Poland were also allowed to seize territories: Hungary occupied southern and eastern Slovakia and a large part of Subcarpathia, which had been under Hungarian rule before World War I, and Poland occupied Teschen (Tesin or Cieszyn), a part of Silesia, which had been an object of dispute between Poland and Czechoslovakia, each of which claimed it on ethnic grounds.

Under the Munich Pact, the Czechoslovak Republic lost extensive economic and strategically important territories in the border regions (about one third of its total area).

19 Czechoslovak Youth Association (CSM)

Founded in 1949, it was a mass youth organization in the Czechoslovak Republic, led by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. It was dissolved in 1968 but reestablished in April 1969 by the Communist Party as the Socialist Youth Association and was only dissolved in 1989.20 Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSC)

Founded in 1921 following a split from the Social Democratic Party, it was banned under the Nazi occupation. It was only after Soviet Russia entered World War II that the Party developed resistance activity in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; because of this, it gained a certain degree of popularity with the general public after 1945.After the communist coup in 1948, the Party had sole power in Czechoslovakia for over 40 years.

The 1950s were marked by party purges and a war against the 'enemy within'. A rift in the Party led to a relaxing of control during the Prague Spring starting in 1967, which came to an end with the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Soviet and allied troops in 1968 and was followed by a period of normalization. The communist rule came to an end after the Velvet Revolution of November 1989.

21 Voskovec and Werich (V+W)

Jan Werich (1905-1980) - Czech actor, playwright and writer - and Jiri Voskovec (1905-1981) - Czech actor, playwright and director. Major couple in the history of Czech theater and in the cultural and political history of Czechoslovakia.Initially performing wild fantasies, crazy farces and absurd tales, they gradually moved to political satire through which they responded to the uncertainties of the depression and the increasing dangers of fascism and war. Their productions include Vest Pocket Revue, The Donkey and The Shadow, The Rags Ballad. In addition, V+W created a completely new genre of Czech political film comedy (Powder and Petrol, Hey Rup, The World Belongs to Us).

22 Slansky Trial

Communist show trial named after its most prominent victim, Rudolf Slansky. It was the most spectacular among show trials against communists with a wartime connection with the West, veterans of the Spanish Civil War, Jews, and Slovak 'bourgeois nationalists'.In November 1952 Slansky and 13 other prominent communist personalities, 11 of whom were Jewish, including Slansky, were brought to trial. The trial was given great publicity; they were accused of being Trotskyst, Titoist, Zionist, bourgeois, nationalist traitors, and in the service of American imperialism. Slansky was executed, and many others were sentenced to death or to forced labor in prison camps.

23 Political changes in 1969

Following the Prague Spring of 1968, which was suppressed by armies of the Soviet Union and its satellite states, a program of 'normalization' was initiated. Normalization meant the restoration of continuity with the pre-reform period and it entailed thoroughgoing political repression and the return to ideological conformity.Top levels of government, the leadership of social organizations and the party organization were purged of all reformist elements. Publishing houses and film studios were placed under new direction. Censorship was strictly imposed, and a campaign of militant atheism was organized.

A new government was set up at the beginning of 1970, and, later that year, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, which incorporated the principle of limited sovereignty. Soviet troops remained stationed in Czechoslovakia and Soviet advisers supervised the functioning of the Ministry of Interior and the security apparatus.

24 February 1948

Communist take-over in Czechoslovakia. The 'people's domocracy' became one of the Soviet satelites in Eastern Europe. The state aparatus was centralized under the leadership of the Czechoslovak Communist Party (KSC). In the economy private ovnership was banned and submitted to central planning. The state took control of the educational system, too. Political opposition and dissident elements were persecuted.25 Skoda Company

Car factory, the foundations of which were laid in 1895 by the mechanics V. Laurin and V. Klement with the production of Slavia bicycles. Just before the end of the 19th century they began manufacturing motor cycles and, in 1905, they started manufacturing automobiles.The name Skoda was introduced in 1925. Having survived economic difficulties, the company made a name for itself on the international market even within the constraints of the Socialist economy. In 1991 Skoda became a joint stock company in association with Volkswagen.

26 Warsaw Pact Occupation of Czechoslovakia

The liberalization of the communist regime in Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring (1967-68) went further than anywhere else in the Soviet block countries. These new developments was perceived by the conservative Soviet communist leadership as intolerable heresy dangerous for Soviet political supremacy in the region.Moscow decided to put a radical end to the chain of events and with the participation of four other Warsaw Pact countries (Poland, East Germany, Hungary and Bulgaria) ran over Czechoslovakia in August, 1968.

27 Samizdat literature in Czechoslovakia

Samizdat literature: The secret publication and distribution of government-banned literature in the former Soviet block. Typically, it was typewritten on thin paper (to facilitate the production of as many carbon copies as possible) and circulated by hand, initially to a group of trusted friends, who then made further typewritten copies and distributed them clandestinely.Material circulated in this way included fiction, poetry, memoirs, historical works, political treatises, petitions, religious tracts, and journals. The penalty for those accused of being involved in samizdat activities varied according to the political climate, from harassment to detention or severe terms of imprisonment.

In Czechoslovakia, there was a boom in Samizdat literature after 1948 and, in particular, after 1968, with the establishment of a number of Samizdat editions supervised by writers, literary critics and publicists: Petlice (editor L. Vaculik), Expedice (editor J. Lopatka), as well as, among others, Ceska expedice (Czech Expedition), Popelnice (Garbage Can) and Prazska imaginace (Prague Imagination).

28 Czech Helsinki Committee

The Helsinki Committee is a major international human rights organization. The Czech branch is primarily concerned with monitoring legislative activities and the state of human rights in the country; it also provides free legal consulting for victims of Human Rights abuse and maintains educational activities.The Czech Helsinki Committee focuses on the penitential system, prisoners' rights, police brutality, minority rights, women's rights, children's rights, labor rights and foreigners' rights.

29 Statni Tajna Bezpecnost (StB)

Czech intelligence and security service founded in 1948.30 Velvet Revolution

Also known as November Events, this term is used for the period between 17th November and 29th December 1989, which resulted in the downfall of the Czechoslovak communist regime.The Velvet Revolution started with student demonstrations, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the student demonstration against the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. Brutal police intervention stirred up public unrest, mass demonstrations took place in Prague, Bratislava and other towns, and a general strike began on 27th November.

The Civic Forum demanded the resignation of the communist government. Due to the general strike Prime Minister Ladislav Adamec was finally forced to hold talks with the Civic Forum and agreed to form a new coalition government. On 29th December democratic elections were held, and Vaclav Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia.