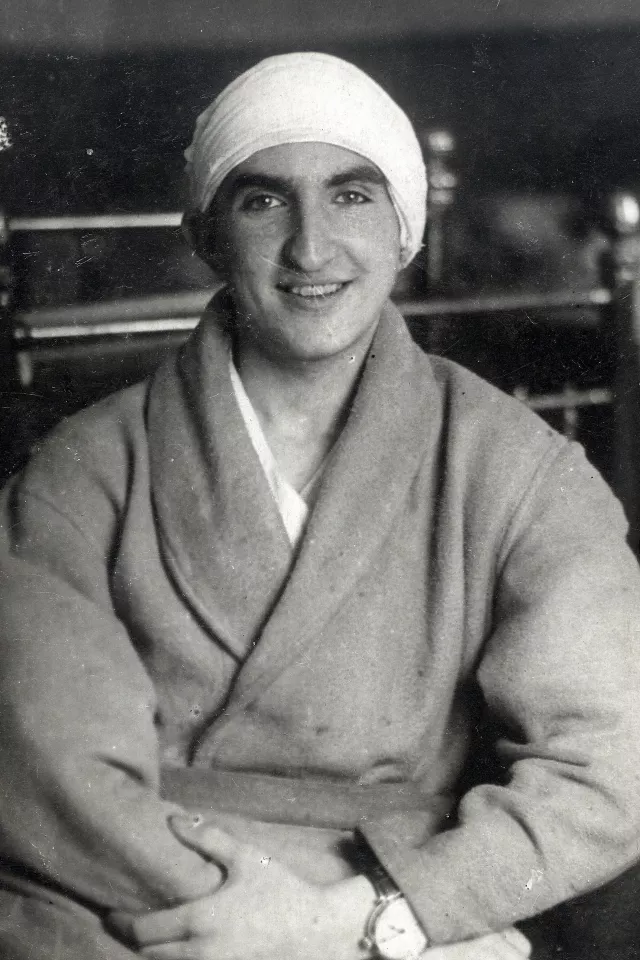

This photograph taken in 1943 shows me in hospital.

We were sent to the Leningrad front. I got to the detached company of snipers in Levashovo (rifle battalion #78). There they taught us about 2 weeks.

The situation there was similar to that at the front-line. We got up at 6 o'clock in the morning (we lived in large barracks and slept in plank beds). We used to run to the lake (it was very cold in the morning), and had to give a souse.

Two weeks later we were sent to the front-line. And it was impossible to ask questions, otherwise you could fall into the hands of SMERSH officers.

We used to sit in trenches. Sometimes they equipped special places for us: in the trees, on the roofs, etc. We were engaged in murder: we had to shoot at Germans. If we noticed a moving target, we fired a shot.

I did not count how many Germans I killed, but my commanders told that the number was about 25 (from October till December 1942). In December we started preparing for the breach of blockade of Leningrad.

The routine was very strict. Sometimes we went on the scout. On the opposite side of the Neva River (near Dubrovka) Germans dug earth-houses. They made real earthworks.

And in their earth-houses they had everything they needed. Later when we took that fortification by storm, we were surprised to find pianos in the German earth-houses.

Our commanders trained us intensively, because Germans poured water over the steep bank of the Neva River (it was 12-14 meters high). Water froze; therefore it was necessary to use long ladders to climb up the bank after crossing the river covered with ice.

On January 12, 1943 we were ordered to fall into line near the bank of the Neva River. The first sergeant arrived carrying a large container. They handed out mugs and said 'Men, come forward!'

All of us made a step forward. The first sergeant came up and filled every mug with alcohol (from the container).

Commanders told us that we had a hard work before us: a capture of the opposite bank of the Neva River, where Germans had entrenched position. We were dressed warmly: short fur coats, quilted trousers, warm caps. But we were inexperienced.

Our commanders warned us that in case of wound, it was better for us to fall down and try to survive. If not, nobody could help us, therefore they considered it necessary to give us a drink. Brother-soldiers were shocked: was it possible to drink, get drunk and go into battle? One guy said 'I refuse to drink.'

The first sergeant answered 'You declared yourself to be a man, but you are not a man yet, join the ranks!' The first sergeant watched us drinking.

I drank half a mug of alcohol. We had nothing to take after, therefore we started eating clean snow. The orchestra began to play; we heard the thunder of cannon. We rushed forward carrying ladders. It became hot.

We were drunk, we ran shouting hurrah. I guess we would have never run forward if we were able to take a practical view of the situation. Around us machine-guns and artillery fired, mines exploded. Germans pushed our ladders back as soon as we pitched them against the bank.

The ladders fell back together with people and people broke their backs and heads shouting with horror and pain. At the same time shells and mines dropped into the Neva River and all this went under. Blood and flesh were around us… It is impossible to describe.

I was not religious, but I believed that every person had his fate. So we rushed into the trenches, killed Germans and hid inside the shell-hole. When we ran out of the shell-hole, a strong blow caught me on my head. I fell down and lost consciousness.

Later they told me there was a big hole in my head, and it seemed that my brain was damaged. The surgeon examined me and ordered to put me closer to the morgue. Nurses dressed my wound smartly. In the outskirts of consciousness I heard that they were going to send me to the hospital in Leningrad immediately.

I found myself in Leningrad in January 1943. When they brought me to the Neuro-Surgical Institute in Mayakovskogo Street, doctor Polenov, the founder of the Institute was on duty. He examined me and ordered to put me on the operating table at once.

[Polenov Andrey Lvovich (1871-1947) was one of the founders of neurosurgery in the USSR.] I was under the knife for 6 hours. After that I was unconscious for a long time. Polenov often came to examine me, and shouted at nurses 'Give him all the best!'

The tastiest meals were on my bedside-table. Later they moved me to the hospital named after Mechnikov. I spent half a year there at the neurological department. There I was surrounded by crazy people, many of them were bound to their beds. My parents knew nothing about me.