Julian Gringras was brought up in a tenement at Sienkiewicza 52, formerly known as Kolejowa Street. The Gringras family's apartment was located on the parlor floor and consisted of three rooms, a kitchen, and a toilet. Within this space, an eleven-member family resided, including Julian, his siblings, and their parents.

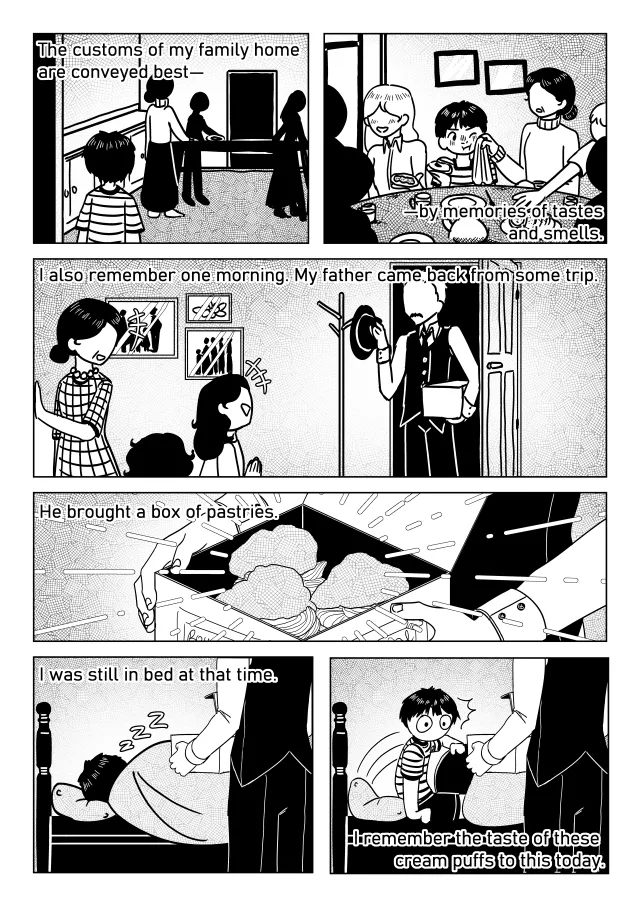

Their house, while not luxurious, was always kept neat. The floor was covered with red wooden planks, and among the most distinctive pieces of furniture were an ornamented cupboard and a piano. In the second room, Fajgla Gringras arranged flowers, which she truly adored.

The kitchen served not only as a cooking area but also as a laundry room. A washerwoman was hired on that occasion, usually working for three days. A large tub with a wringer occupied a significant portion of the room, which for the young Julian meant a less-than-full meal, as access to the kitchen was restricted, and meals were prepared hastily. The kitchen housed a coal stove with four hotplates and a bed for the maid, while a bathtub for the youngest children was brought up from the basement.

On the second floor of the annex, above the Gringras' apartment, lived the Herling family, from which Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, a Polish writer and essayist, originated. However, the boys didn't know each other too well due to the age difference. There was also a bakery below the apartment, which, especially in the summer, posed problems due to insect infestations. They were compensated for this inconvenience by delicious cholent, a traditional Jewish dish made there, which was enjoyed by Kopel Gringras, the father of Julian Gringras.

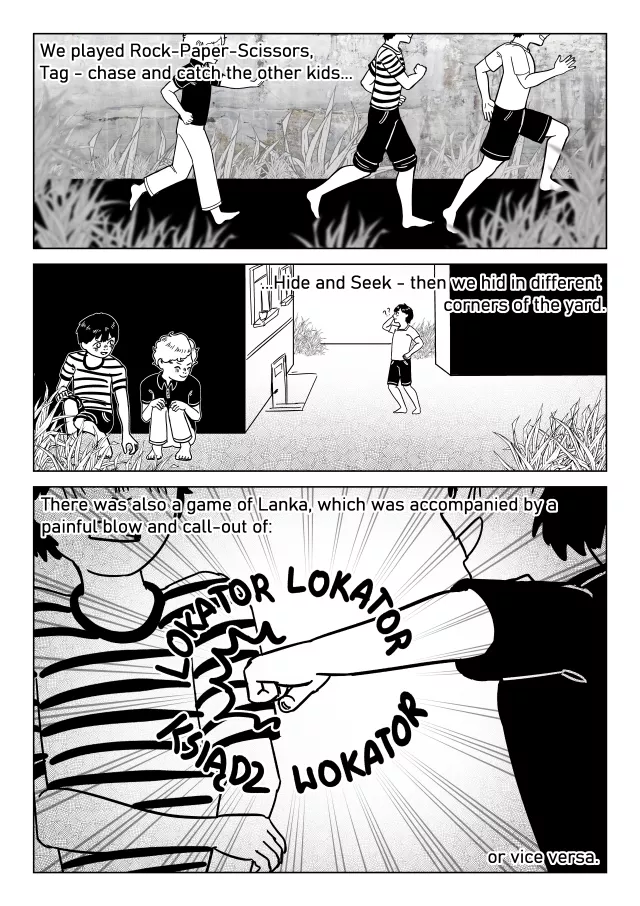

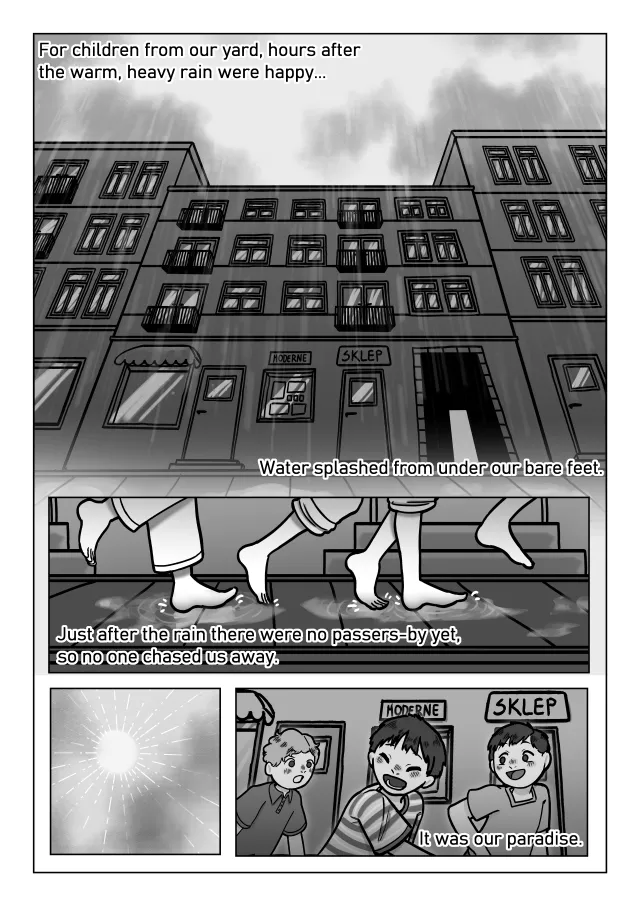

An important aspect of Julian's childhood was the tenement backyard. It was a long, narrow space bordered by the river on one side and the tenement building on the other. There were storage sheds for firewood and residents' belongings on one side, while on the other stood a considerably more impressive barn - walking across its roof was the proof of great bravery. Hours spent outdoors were filled with games like „nożyki”, „gonitko” (game of tag), „krytko” (hide-and-seek), or „lanka”.

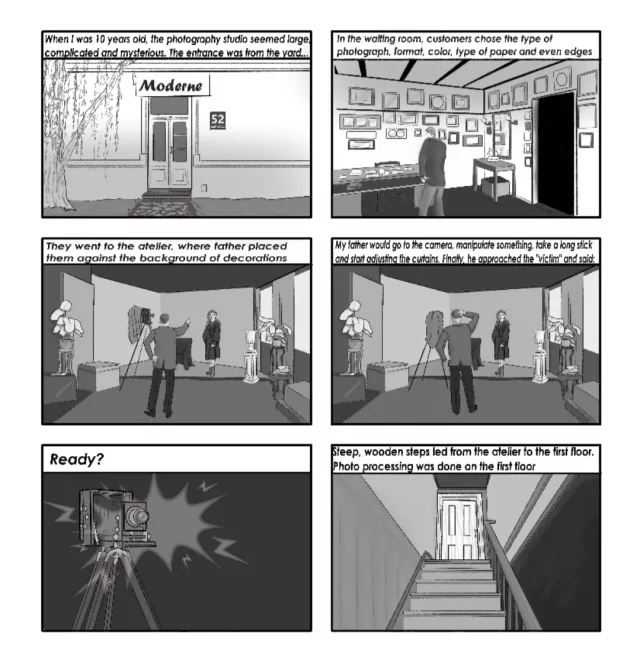

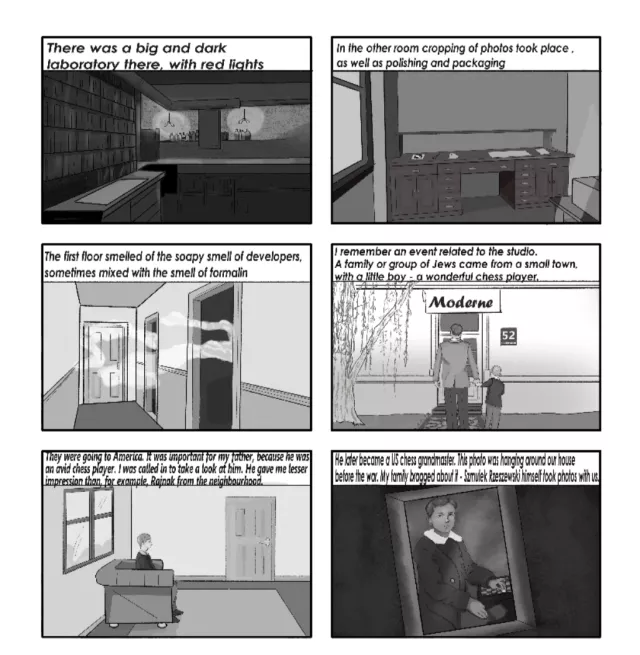

Adjacent to the barn was the photographic atelier, part of the Moderne studio, which belonged to Julian's father. It was a lightweight but sturdy construction, with a glass roof and frosted windows. Initially, the lighting inside was adjusted using blinds, but in the 1930s, electric lamps were installed. In this space, the clients were positioned, settings and props were selected, and then photographs were taken. This was the task of Kopel Gringras and his older sons. One entered the studio from a small room next to it, which housed the cash register, where orders were placed. One day, Samuel Rzeszewski, then only ten years old, was photographed there. He turned out to be a future chess prodigy.

Photo processing took place in a separate space - a brick extension of the studio, equipped with gear for enlarging, developing, and retouching photographs. Typically, no more than three people worked there, including Julian's cousin, Maurice Chitler.

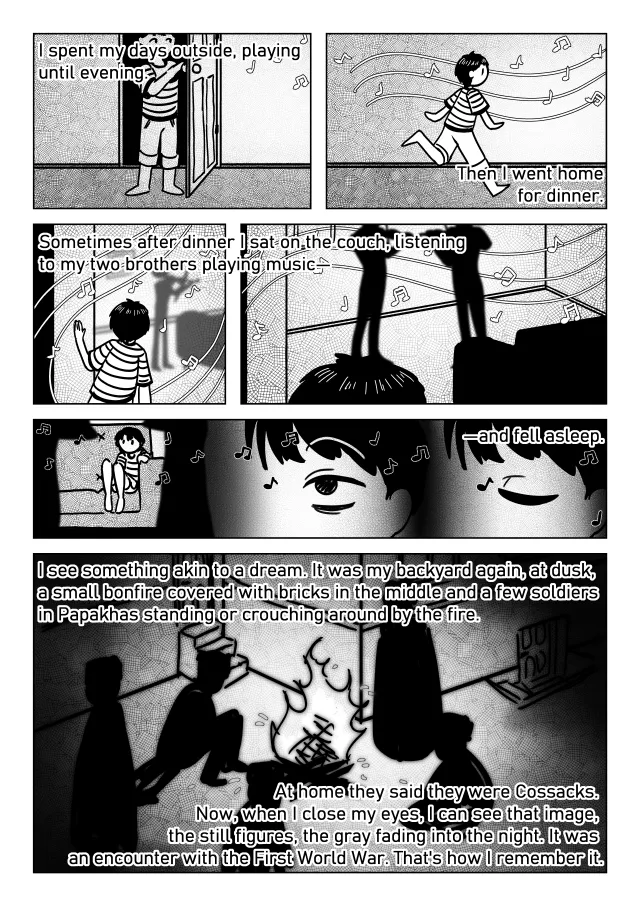

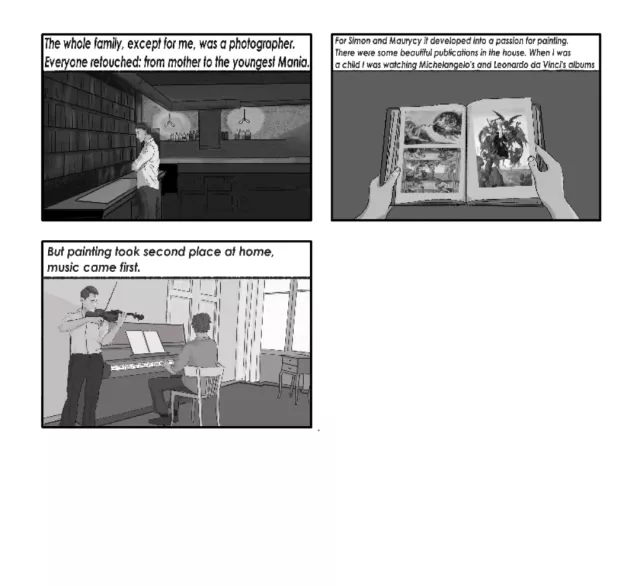

The work wasn't just limited to tasks performed in the studio. At night, Fajgla Gringras would retouch photos by hand, using a special solution to cover light spots on the negatives. Meanwhile, Kopel Gringras, with a firm brush dipped in paint, would tap out the outline of the picture, producing prints with a characteristic grainy structure. This was known as the Bromoeldruck technique. Young Julian would often observe his father at work before falling asleep.

Across from „Moderne” was the „Rembrandt” photographic studio. It was the main competition for the Gringras family, and its owner was also of Jewish descent. His name does not appear in Julian's story. People in the city only referred to him as „Rembrandt” just as Kopel Gringras was called „Mr. Moderne”.