Ludmila Rutarova

Ludmila Rutarova

Prague

Czech Republic

Interviewer: Dagmar Greslova

Date of interview: February 2007

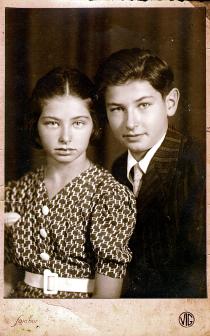

Ludmila Rutarova is from a secularized Jewish family from Prague. She spent a significant part of her childhood at her aunt's in Nadejkov, near Tabor, where she received a Catholic upbringing. Ludmila's parents owned and operated a general store in Na Morani Street. Ludmila Rutarova attended Sokol 1 from childhood, and likes to recall the spirit and atmosphere of Sokol gatherings; she also exercised as a teenager at the last prewar All- Sokol Slet [Rally] in Prague in 1938. During the time of the Protectorate of Böhmen and Mähren 2 she had to leave Sokol due to being a Jew - she received satisfaction after November 1989, when she was invited into 'The Sokol Vysehrad Old Guard,' in whose activities she likes to participate. During the Protectorate of Böhmen and Mähren she was fired from work, and was forced to perform menial work. She tried to escape from Hitler with her boyfriend to Canada, for which reason she had herself with great complications secretly baptized in 1939; however even despite this, escape to Canada did not succeed in the end. The anti-Jewish laws 3 affected the entire family in a fundamental fashion, when they were first ordered to wear a six-pointed star 4, their property was gradually confiscated, they were denied access to public places, to parks, cinemas and theaters, and the family was forced to liquidate its general store. Deportation of Ludmila's brother to Terezin 5 in November 1941 followed, where and other men from AK1 and AK2 prepared the ghetto for residence. The rest of the Weiner family was transported to Terezin in March 1942. Ludmila worked in the so-called 'Landwirtschaft' [agriculture], and in her spare time participated in cultural life - she played in many operas under the leadership of Rafael Schächter [Schächter, Rafael (1905-1944): conductor, choirmaster]. Ludmila Rutarova's relation of this time is very detailed and alive, enabling the reader to peer closely into everyday life in the Terezin ghetto. From there, Ludmila and her brother followed their parents into Auschwitz-Brezinka in 1944, and were put in the so-called family camp 6. In Auschwitz she worked in the children's block, filling the children's time with playing, singing and drawing. After a two-month stay in Auschwitz, she and her mother were selected in July 1944 to be among a thousand women picked for slave work in Hamburg. Towards the end of the war, these women prisoners were transported from Hamburg to the Bergen- Belsen 7 concentration camp. After the liberation of Bergen-Belsen in April 1945, Ludmila fell ill with a serious typhus infection. In July 1945 she and her mother returned to Prague, where they met up with her brother Josef, who survived the war. Ludmila's father, like the rest of the extended family, was murdered in Auschwitz. After the war Ludmila married Karel Rutar, with whom she had the common experience of wartime events. Karel had been in Terezin and Wulkov. She soon became a widow, and raised two children. Speaking with Ludmila Rutarova was very interesting - even more than sixty years after the events of World War II, she is able to tell her story in a very lifelike and detailed fashion.

Family background

My grandfather on my father's side, Simon Weiner, son of Moses and Ludmila Weiner, died before I was born, so I don't remember him. Grandma Frantiska Weiner, daughter of Simon and Terezie Lederer, died even earlier than Grandpa Simon. After Grandma died, Grandpa married her sister. My grandfather's second wife lived in Prague on Stepanska Street; I remember that when it was her birthday, I used to always go to recite poems to her, and she'd also occasionally give me a five-crown piece. [In 1929, it was decreed by law that the Czechoslovak crown (Kc) was equal in value to 44.58 mg of gold.]

My father [Alfred Weiner] was born from Grandpa's first marriage, from which he had siblings Hedvika, Viktor, Zofie and Marie. Born from Grandpa's second marriage were Ida [had a son, Josef], Erna, Berta [had a son Karel and a daughter Anna], Anna and Emil. Uncle Viktor Weiner lived in Pacov with his wife Marie and his daughters Elsa and Hana. As a child, I liked going to his place during vacation, and used to play with Hanicka [Hana], whom I liked very much. Uncle Viktor had a leather goods factory; they used to make purses and suitcases. The factory burned down, and my uncle had to take out a large mortgage. We later lived with my aunt and cousins in Terezin during the war, where my uncle died. Everyone in the family perished in Auschwitz during the war, as they were included in the first so-called family transport.

I barely remember my grandparents on my mother's side; Grandpa Jachym Winternitz died when I was only a year old. The Winternitz family's ancestors were originally Czech brethren. [The Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren: was created in 1918 by the merger of the Augsburg Evangelical Church and the Helvetia denomination. Its roots, however, lay deep in the Czech Reformation beginning in 1781.] But our ancestor didn't want to emigrate, and if he wanted to stay, he had to change his name to a German one - as his name was Zimanic [a combination of the Czech words winter - zima - and nothing - nic]. This was because as a glazier he had no work in the winter. He changed his name to the German Winternitz, and converted to Judaism.

I faintly remember Grandma Aloisie Winternitzova, née Vocaskova, who was quite ill; she had a bad case of dementia. All I remember is my mother bringing me to Černovice as a little girl to show me to her, but at that time Grandma was already badly off, and was no longer communicating.

My mother, Helena Weinerova, née Winternitzova, was born in 1896 in Cernovice, by Tabor. My mother's siblings were Leopold, Karel, Ema, Ota, Marta, Gustav and Ruzena. In 1912 my mother's sisters Ema and Marta were going to America. They were in England, waiting for a ship, and in order to pass the time they went dancing. They were young, wanted to have fun, the dancing kept going, and so they missed the ship. They had no idea how lucky that was, because their ship was the Titanic. That's fate. When their parents found out that the Titanic had sunk, they were desperate, but Ema and Marta wrote home that they'd missed the ship, and so had taken a different one. In the end they both remained in America.

My father always liked to talk about how my parents met. In Cernovice my mother knew someone named Emil, they'd been going out together for several years, and it was already clear that they'd be getting married. When Emil came to ask Grandpa for my mother's hand, he was interested in what sort of dowry my mother would get. When my grandfather listed everything she would get, Emil asked whether she would also get a cow for her dowry. To this my grandfather answered that she wouldn't get a cow. My mother was listening behind the door, and when she heard this, she said: 'You wanted a cow? So marry a cow!' and left for Prague. In Prague she met my father, and married him out of spite.

Growing up

I was born in 1920 in Prague. I had a brother, Josef, two years younger. I was a very skinny kid, and my parents used to take me to see some Dr. Vit in Smichov. The doctor didn't want to let me go to school, that I was too skinny and weak. But my mother was afraid that if I didn't go to school I'll fall behind, and so my parents decided to send me to Aunt Zofie née Weinerova's and Uncle Josef Weiger's in Nadejkov, near Tabor, to improve my health. Auntie Zofie was an awfully kind woman, and I loved her very much. My childhood in Nadejkov was a very beautiful time, Auntie had a farm, and it was really swell there.

I lived at my aunt's for one year before I went to school, and then I attended elementary school in Nadejkov for another two years. I was the only Jew in the entire school, so when we had Catholic religion class, I could choose whether to go or not. But my aunt didn't know where I could go during that time, so she asked Father Vesely if I could attend Catholic religion class together with the other children. The priest didn't object, so for two years I attended Catholic religion class. I was always a model student, and so thanks to Father Vesely, I know all the prayers perfectly. Our Father, Hail Mary! After three years of life in Nadejkov, I returned to Prague to my parents.

We lived in Prague on Na Morani Street, near Palacky Bridge. We had a servant, Helena, who was a 'schlonzachka,' which means that she was from somewhere by Ostrava, and spoke in their dialect - a little Czech, a little Polish. I remember that when there were elections, I asked Hela whom she'd voted for. She told me that she's a 'schlonzachka,' and so of course has to vote for the Communists!

My parents had a general store where they sold various goods: fruit, vegetables, baked goods, butter, eggs, milk, coffee, tea, sugar, sometimes even chickens and geese. I didn't like being in the store too much, because I had to help! My parents rose early in the morning and would go to the market close to Narodni Trida [National Avenue] for vegetables, fruit, eggs and other goods. At the market, when they'd see our mother approaching, they'd say: 'The countess is coming,' because she used to root around in the goods. [The Czech word for countess is "hrabenka," while the expression for rooting or digging around is "hrabat."] The market was this big lot, and my parents used to run into various storekeepers there. The Novaks, greengrocers, were from Květuš, close to Nadejkov, where I'd lived for three years, so I would occasionally go with them during the holidays.

During the time of the protectorate we had to close the store and move in to one room. Before that we we'd been living in the building where our store was, and we had a small apartment - one room, a kitchen, and a larger front hall. My father didn't want to live anywhere else other than the house where we had our store, so he'd be close to work.

We were basically a secularized family; we didn't live in any especially religious fashion. We observed Christian Christmas, and also used to have a tree. We didn't cook kosher 8, and as far as I know from what I was told, even my grandparents' families didn't cook kosher. We observed Passover at home about once or twice, because my brother and I liked matzot, and so because of us my mother made seder. My father would only go to the Jerusalem Synagogue for the Long Day [Yom Kippur] or New Year [Rosh Hashanah], I don't even know exactly which of these holidays. Once, when my brother and I were small, we also went to the synagogue together with our father. I remember that when the rabbi was singing, we found it funny and were killing ourselves laughing, so they threw us out of there.

I attended Sokol from childhood; I was a frenetic Sokol girl! I belonged to the Sokol in Prague, Scheiner's Zupa [Župa - a group or unit]. As a teenager, I exercised at the last prewar All-Sokol Slet [Rally] at Strahov Stadium in 1938. I liked Sokol a lot; I'd meet my girlfriends there, the atmosphere was friendly and pleasant, and we also used to perform so-called Maypoles and Beseda [ceilidh] gymnastics. During the war, as a Jew, I had to leave Sokol. After 1989 9 I was invited to join the Sokol Vysehrad Old Guard.

In Prague, starting in Grade 3, I attended the Na Hradek girls' public school on Vysehradska Street. There we were taught religion by Rabbi Schrecker, but in any case what I liked best was when he sent me for the class index - I'd always secretly peek into it, found out what marks we'd get on our report cards, and could then tell my girlfriends. Then I attended business school, and absolved my last year in a reformed school on Legerova Street.

After school I was employed as a clerk at Tauber & Fisl in Praha-Vysocany. Because my father was their cellar-master, and the salesmen that used to come to the store to offer goods recommended the position to me. The first pay packet I got was 120 crowns. I had to leave because the political situation was starting to become unpleasant - as a Jew I wasn't allowed to be employed as an office worker.

My brother Pepik [Josef] wanted to attend a business academy on Resslova Street, but the situation was already bad, so he didn't get in. My father was afraid that he might have to join the army, so they sent my brother to Ringhoffer, to Tatra, to apprentice as an auto mechanic. After the war he became the youngest master [mechanic] there. We had a cousin, Josef Weiger, who was the same age as my brother. My cousin also couldn't attend school, so was apprenticing as a tailor, once he boasted to us that he already knew seven [different types of] stitches. From that time on my brother and I called him 'Seven-stitch Pepik.' He used to often come visit us, but was terribly timid and shy; he wouldn't come in on his own, he wouldn't sit down on his own, and we constantly had to prod him along into something. So my brother composed a poem about him:

When you ring at our door, why does your hand shake, and when finally in the kitchen, why do you quake. Why don't you know what to do with your coat and hat, why are you such a chicken, if I may please ask that. Because you're an idiot, my boy, and a huge one, but that's known not just by me, but by everyone. How many times against your mug my hand rose in malice, just to fall again, I suffer on, the tortures of Tantalus. Just chess, that you know, one could say almost with class, but even during this game, I'd love to kick you in the ass. Come over again, darling, it'll do our hearts good, my boy, 'cause with your departure again, you'll cause them great joy.

During the war

During the war, my knowledge of Catholicism that I had gained in school in Nadejkov came in very handy. This is because I was going out with a young man who wasn't a Jew, but we did want to escape Hitler together, to Canada. We absolved all sorts of medical checks so that we could leave the country, but another condition for leaving the country was for me to be baptized. At that time my mother made the rounds of all the churches in the neighborhood, everywhere they were very kind, but told us that they alas couldn't baptize me because that was prohibited. Because it was already 1939, right before the occupation, and priests had already been forbidden to baptize Jews. In the end we managed to find some highly revered priest at the diocese in Hradcany, who said he'd be able to arrange a baptism for me.

I remember setting out for Hradcany, I was not quite nineteen at the time, I don't remember all the titles by which I had to address the man, but he was actually a very nice person. He told me he knew a priest in Nížebohy who'd be willing to baptize me. But that prior to that I'd have to learn various prayers and recitations, so he brought me a book which I was supposed to read, and said he'd test me on it before I was to undergo the baptism. I opened the book, and told him that I didn't need it, that I knew it all. He was very surprised, and asked how it was possible. I told him that I'd attended Catholic religion classes for two years. He asked me if it wouldn't upset me if he tested me anyway. It was no problem for me of course; on the spot I recited all the prayers for him, Our Father, Hail Mary, and Lord, I Believe one after another. He was completely flabbergasted, and said I knew it so well that I didn't need any book of his, and that he'd go ahead and arrange my baptism.

I was baptized by Father Culik in Nížebohy, who even arranged a banquet for me to go with it, and was very kind to me. However, in the end I didn't leave for Canada anyway, because my young man and I had broken up!

During the war, when things were unpleasant, my parents told me to not go to work anywhere, and to instead help out at home with the housework and cooking, because, of course, at that time we no longer had a servant. I couldn't work in an office, because no one would take me on anywhere. Finally some Mr. Valasek gave my cousin Inka [Frantiska] and me jobs in a cartonnage workshop, where we were gluing cardboard boxes together. At first our boss was quite happy with us, telling us how handy we were, how good we were at it. We got to know the young girls that worked there. Together we'd make the boxes, sing songs, and go to a tavern for soup.

Once during lunch, my cousin Inka asked one girl whether our boss was making health insurance payments for us. The girl told her that she didn't know. On payday that girl asked the boss about the insurance. He became enraged and asked her how that had occurred to her, and who'd told her that he was supposed to pay something like that. And so it happened that Boss Valasek summoned Inka, although up to that point he'd always been formal and polite to her, and started yelling at her: 'I'll catch you by your ass and throw you out the door!' So we both left, the job wasn't all that great anyway, our pay was about 100 crowns.

Inka and I found another job, at the Hunka bookbindery on Podskalska Street. Mr. Hunka was a Czech, and was an excellent and fair person! The entire Hunka family worked in the bookbindery - his wife and daughter, as well as his sister-in-law. There I learned to stitch and bind books, to gild the headings with real gold; it was very nice work. I worked there as a bookbinder up until I went into the transport.

Gradually various edicts were issued ordering Jews to hand in various things - my brother had to hand in his Jawa Robot motorcycle, so he gave it to some friends, who hid it in their cellar under some coal. I was supposed to hand in my skis and ski boots, so I hid them with a girlfriend, and our neighbor hid my typewriter for me. We also had to hand in all gold and jewels.

Basically we weren't allowed anything back then - we weren't allowed in the theaters, we weren't allowed in the cinema, we weren't allowed to go to the park, we could only ride in the rear car of the streetcar, and we of course had to wear a star. Later came [another] prohibition and I was no longer even allowed to attend Sokol.

Once a friend and I went to accompany my cousin from Na Morani up towards Charles Square, I was walking between them, and a newsboy carrying papers was walking towards us, pointed at me and yelled: 'Whoever associates with Jews is a traitor!' Once my cousin Inka and I went dancing, even though it was already forbidden. Suddenly some Germans appeared there, so we quietly ran away. But I have to say that otherwise I didn't run into anti-Semitism, as everyone in our neighborhood quite liked our family, plus we weren't conspicuous in any way so as to stick out, so there was no reason for any sort of grudges or envy.

My brother Josef left in November 1941 on the second transport to Terezin, AK2, or 'Aufbaukommando' [German for 'Construction Commando']. From that time on we didn't have any news of him, because the men from AK1 and AK2 weren't allowed to write home. When someone wrote home, they were shot. I, along with my parents, went on the transport in April 1942. The assembly point in Holesovice, by the Veletrzni Palace, where we waited for about three days for the train to Terezin, was horrible.

We were all gathered in this huge hall, which is no longer there today, where there was absolutely nothing, just columns along the sides. Everyone got a mattress to lie on. As far as toilets and washing facilities go, they were catastrophic. After about three days, a train took us to Bohusovice, where the tracks ended, because the spur line to Terezin hadn't been built yet. So we walked from Bohusovice to Terezin, and dragged our luggage along.

I remember that as soon as we arrived, some guys I didn't know were calling out my name, 'Liduska,' and immediately started helping me with my suitcase. They were guys who worked for the 'Transportleitung' [German for 'transport management'] helping the arrivals with their luggage. They recognized me right away, even though they'd never seen me before, as I supposedly looked a lot like my brother, who was already in Terezin. My brother Pepik was living with them in the Sudeten barracks.

At first my brother Pepik worked in the 'Hundertschaft,' which was 100 guys that helped people with their luggage upon arrival. Then he went to work in the barracks, where they were sorting things from stolen suitcases. His boss was SS-Scharführer [squad leader] Rudolf Haindl. The work consisted of sorting luggage contents - food was put in one place, clothing in another, and so on. Pepik was clever, and so a couple of times it happened that during the sorting he'd for example come across a shaving brush that he'd screw apart and find money hidden inside. However that was handed in, because what good would money have done us in Terezin?

At first they put us up in the basement of the Kavalir barracks, just on some straw. We were there until they placed us somewhere. You just picked a spot, and that's where you slept. My father then stayed there, and my mother and I went to the Hamburg barracks. Initially we were living on the ground floor, where I got sick, I had some sort of flu, and spent most of my time in bed. They then moved us to the first floor to room No. 165, where about fifty of us women lived together.

I remember that when I arrived in Terezin, on Thursday we had dumplings with this brown gravy, I don't even know anymore what it was made from, probably from melted Sana [margarine]. When I got it, I said that I wouldn't eat this, and so gave it to my cousin Karel. My cousin told me that this was the best food you could get in Terezin. Otherwise, we got only bread and soup.

In Terezin my mother worked as a 'Zimmerälteste' [senior room warden], so she was in charge of the entire room, she'd always be issued food and then would distribute it. She also did 'Stromkontrolle' [i.e. she was in charge of electricity], so she had to walk around the rooms and check whether, despite it being prohibited, anyone wasn't cooking or otherwise wasting electricity. People, of course, brought hotplates with them, but only those who had special permission were allowed to use them.

Terezin had a special currency, so-called 'Ghettogeld' - I think they were ten, twenty, fifty and hundred-crown bills - which we'd get for doing work. There were a couple of shops in the ghetto where you could get things that had been stolen from people that had arrived in Terezin. We could buy these goods - for example bed sheets, towels, and dishcloths - with 'Ghettogeld.' There were grocery stores, but all you could get in them was vinegar and mustard, basically nothing. I bought myself a pair of beautiful high leather 'Cossack' boots there, I loved wearing them, and finally took them with me on the trip to Auschwitz - but we went there in May, and my feet were terribly hot in them, so I cut the tops off.

The entire time in Terezin, I worked in agriculture, in the so-called 'Landwirtschaft.' We'd always assemble, and initially we used to go to Crete [an area beyond the ghetto's borders] to hoe carrots, thin out beets, cultivate tomatoes, shuck beans and all sorts of other things. In the winter we made straw mats for greenhouses. Once in Crete I was hoeing carrots, and found a buried bundle of money! And it was a lot of money, in Reichsmarks! I told my friend Hanka, with whom I worked, and we split the money in half.

The next day Hanka came and told me that she couldn't keep the money, that her family was afraid. You see, her brother-in-law worked for the Terezin staff, and she was afraid that if it was discovered that we'd found money and kept it, her brother-in-law could have problems. I then came home and told my mother that Hanka had returned the money to me. My mother told me: 'If Hanka won't keep it, neither will you!' The next day Hanka and I went to hand in the money to the 'Landwirtschaft,' where two brothers, Tonda and Vilda Bisic were in charge. They must have thought we were crazy for not keeping it, but what could they do. Vilda wrote up a protocol, that we'd handed it in.

In Terezin I got to know Regina, a girl I worked with in the staff garden, where we cultivated cucumbers and other things. We used to steal the cucumbers, but I didn't know how to steal much, I was bad at it. Regina on the other hand was clever, she'd always pluck one for me and tell me: 'Just stick it in your bra!' So I'd stick it in my bra, and could smuggle something into the ghetto for my parents.

One day some Weinstein came by, people called him 'Major,' I don't even know why, and was looking for some handy girls. My friend Hanka and I put up our hands, were issued baskets and a ladder, and from that time onwards picked fruit. All told, there were only four of us girls from the ghetto picking fruit; it was good work, because while working I could eat as much fruit as I could. We picked pears, apples and other fruit in the ghetto in gardens where there were fruit trees that had belonged to people that had lived there. We had to put the fruit in crates and it was then shipped to an army hospital, to Crete, for sick German soldiers.

Our boss, Mr. Stern, and his daughter used to accompany us while we worked, then one older German who didn't know even a whit of Czech, and one young guy. Then there were three Germans that took turns, Haam, Altmann and Ulrich, who lived in Crete. Everyone was afraid of Haam; he had these bulging eyes, but was quite kind to us. He treated us well; every other day he'd bring us lunches. Other times he'd for instance warn us to not steal anything, that there were nasty guards at the gate, such as Sykora or Ullmann, for example.

When it was cherry season, we used to go up on the ramparts to chase away starlings. My brother Pepik once brought me a nice watch, the kind that people used to wear way back when, on a clasp. He'd found it while sorting confiscated luggage. Haam really took a liking to this watch, and was always saying: 'Lida, that's a beautiful watch!' But it didn't mean anything to me, just that I knew what time it was. Once I lost it while picking fruit. Haam made a great fuss, he was so unhappy over that! He walked from tree to tree and looked for my watch in the tall grass, and, of course, he didn't find it.

Another time Haam heaved this sigh, and said that his daughter's name day was coming up, and that she'd really like a purse. He didn't say it because he wanted me to give him one of mine; he just sort of heaved this sigh. I asked my brother if he couldn't find a purse for me. The next day Pepik even brought two - a black one and a white one, so that there'd be something to choose from.

When I gave them to Haam, he couldn't believe it, and kept asking how he could repay me. He asked me what I liked best. I said to myself, if he wants to know what I like best, I'll just go ahead and tell him, he wouldn't be able to arrange it anyway. I told him that what I liked most of all was fish. He didn't say anything to that. The next day he actually brought me a fish! And he told me: 'But do you know where you have to stick it?' Boy, did I stink, a fish in my bra! But the fish was good; my mother prepared it in a very tasty fashion.

In the fall we used to go to the river, the place was named Erholung, and there was an alley of nut trees there. Men would beat the trees, and we'd gather them from the ground into baskets. I like nuts a lot, but there I ate so many of them that I got terribly sick. Hanka and I had this idea that it would be pleasant to take a dip in the Ohra; we were sweaty, it was September, and we wanted to go swimming. Hanka and I went to see Haam, and said to him: 'Mr. Haam, it's such a shame, do you know how many nuts fall into the water while the trees are being beaten, and float away? Couldn't we catch them in the river with a basket?' Haam praised us for having such a good idea.

So the next day we took our bathing suits and went swimming. But the water was already cold, and what's more, because we were wearing bathing suits, we couldn't smuggle nuts into the ghetto. So we got dressed again and went gathering. Haam was quite kind to us, but otherwise everyone was afraid of him, and it was said that he was nasty.

Once we were picking pears in the garden behind the school in L 417, there's a wall there that the pears were falling behind. Lots of people gathered behind the wall, to take some pears for themselves. When Haam saw that, he ordered me to go behind the wall, gather the pears there, and if someone came and wanted to take the pears for himself, to call him over.

I was gathering them for a while, when this young guy came over to me and wanted me to give him some pears. I told him that if it was up to me, I'd give them all to him, but I warned him that there was a nasty German behind the wall, and that he'd catch him. I dropped one pear and he wanted to take it, I told him not to do it, that Haam would catch him. He took it anyway.

Haam saw him, grabbed him and took him to Headquarters. I felt awfully sorry for him, but there was nothing I could do. Other times I managed to smuggle in fruit, but it had to be arranged ahead of time - two girls, Lilka and Rita Popper slept beside me in the block, so I arranged it with them that when I went picking, I'd come back to the block to go to the toilet, leave them some pears on the toilet lid, and they'd then pick them up. That's how we pulled it off.

In Terezin I sang for Rafael Schächter in 'The Bartered Bride' [opera by Czech composer Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884)], in 'The Kiss,' in 'The Czech Song,' and in the 'Requiem' by Giuseppe Verdi. Initially we practiced in a cellar, where the piano was. We were organized by voice, and got parts that someone was rewriting. The National Artist Karel Berman [Berman, Karel (1919 -1995): Czech opera singer and director of Jewish origin] would come to sing the solo bass parts, later he picked fifteen girls, among them also me, and with him we prepared the opera 'Lumpacivagabundus' [humorous satire by Austrian playwright Johann Nestroy (1801-1862)] and the 'Moravian Duets' [by Czech composer Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904)]. We sang in attics and in our spare time, as well as in the gymnasium of the former Sokol Hall. I also saw Hans Krasa's 'Brundibar,' the kid that played the role of Pepicek, used to come over and helped Schächter turn the pages of the notes. [Editor's note: The children's opera Brundibar was created in 1938 for a contest announced by the then Czechoslovak Ministry of Schools and National Education. It was composed by Hans Krasa based on a libretto by Adolf Hoffmeister. The first performance of Brundibar - by residents of the Jewish orphanage in Prague - wasn't seen by the composer. He had been deported to Terezin. Not long after him, Rudolf Freudenfeld, the son of the orphanage's director, who had rehearsed the opera with the children, was also transported. This opera had more than 50 official performances in Terezin. The idea of solidarity, collective battle against the enemy and the victory of good over evil today speaks to people the whole world over. Today the opera is performed on hundreds of stages in various corners of the world.]

Before I left Terezin, there was a Red Cross visit being planned, and we had to do so-called 'Verschönerung,' or beautification. Terezin was to be decorated, for the sake of appearances, to fool the Red Cross delegation. However, I wasn't there to see the Red Cross visit. I was in Terezin from April 1942 until May 1944, when I left with my brother for Auschwitz. My mother and father left on the first May transport for the so-called family camp, and my brother and I left on the third one in May 1944. When my brother and I were boarding the train, Haindl came walking along, and when he saw Pepik and me, he was surprised that we were leaving, and asked why we hadn't come to tell him we'd been included in a transport, that he could have gotten us off it. To that Pepik told him that our parents were already in Auschwitz, and that we had to leave to go join them.

When the train stopped in Auschwitz it was already dark, and we could hear them bellowing 'Raus, raus.' We got out and were ordered to leave all our bags there; they told us that we'd get them later. Of course, we never saw our bags again. They only thing we were left with was what we were wearing and in our hands. I had some sardines, a flashlight and about a hundred marks on me. My cousin Inka, who was already in Auschwitz, worked as a housekeeper for some German who worked in the 'Kleiderkammer' [the place where clothing that had been confiscated from incoming transports was sorted, searched for hidden valuables, and then shipped to Germany for distribution]. Although at the time we arrived at the camp there was a 'Lagersperre' [camp closure] on and no one was allowed out, some could, Inka being one of them. She noticed me and called out to me: 'Throw me everything you've got!' So I threw my things to her, and thanks to this they were saved.

The Poles were very cruel, and beat us with sticks. We lined up five abreast, walked along and saw the sign 'Arbeit macht frei' [German for 'work shall set you free'] above our heads. Some Pole walked along with us, who told us that if any of us knew how to write well, we'd have it good in Auschwitz. Several girls worked as so-called 'Schreiber,' as office assistants, and each block had one 'Schreiber.'

In Auschwitz they tattooed us, and I got No. A 4603 [Editor's note: In order to avoid the assignment of excessively high numbers from the general series to the large number of Hungarian Jews arriving in 1944, the SS authorities introduced new sequences of numbers in mid-May 1944. This series, prefaced by the letter A, began with "1" and ended at "20,000." Once the number 20,000 was reached, a new series beginning with "B" series was introduced.] I'd counted the line as it walked in front of me, and positioned myself so that the sum of my number was 13. I'm superstitious, and I said to myself that if the sum of my number's digits would be unlucky 13, I'd survive the war.

Then they assigned us to blocks. Then the block leader yelled at us that we were all to go outside and leave everything inside. I'd noticed that the block leader had been talking to a friend of mine with whom I'd worked in the 'Landwirtschaft' in Terezin, Dina Gottliebova, who'd arrived on the first September transport. I had absolutely no idea of Dina's status in the camp. I went over to Dina and told her that the block leader had ordered us to leave all our things inside - Dina told me to go back and take everything with me. The block leader noticed it, but didn't object, because she knew that Dina had privileged status.

Dina was the lover of 'Lagerältester' [camp elder] Willy, thanks to which she saved herself and her mother from the gas. Dina was a swell girl; before the war she'd attended art school in Brno, and could draw beautifully. Mengele hired her to draw Roma in the 'Gypsy camp' for his 'research.' Dina also drew for the children in the children's block. It was from Dina Gottliebova that I found out that the Nazis were murdering people in gas chambers in Auschwitz. She told me that she was sure of it, because she'd gotten to see the gas chambers, which she'd also drawn. When I found out about the gas, I cried for three days. I saw huge flames flaring, two meters high.

I lived in a different block than my mother, as she'd already been in Auschwitz for some time. But we were able to see each other, as well as with my brother, father, Auntie Zofie, and my cousin Inka. I tried to go for visits to see Auntie Zofie, she was in a bad way, as she was over sixty and she had a bunk that she had a hard time getting to. I tried to occasionally bring her some food.

I was working in a block with the smallest children, about three or four years old. I played with them, told them poems and sang with them. When the weather was nice, I'd also go play with them outside in front of the block. Across from us were wire fences, the inner ones not electrified and the outer ones electrified. I gave the children lunches and in the evening I'd bring them rations to their block, where they were living with their mothers. Children got somewhat better food than the others, somewhat thicker milky soup and milk.

Packages would arrive in Auschwitz, intended for prisoners, many of which were already dead when the packages arrived. We were given what remained of the packages, and picked out things for the children - for example remnants of cookies that had broken along the way, and other things.

None of these small children, of whom I was responsible for about twenty, survived. Only several older ones survived, boys of about fifteen who walked around Auschwitz during the day and called out various information - they for example called out in German 'bread' or 'soup' when food was being distributed. These boys passed the selection prior to the destruction of the family camp, and were transported from Auschwitz to other concentration camps, thanks to which they lived to see freedom.

Pepik worked in the 'Rollwagenkommando' - men were harnessed instead of animals, and dragged heavy loads behind themselves. They had a wagon on which they transported corpses out of the camp, and would bring bread or other things back on the wagon. In the 'Rollwagenkommando,' Pepik also got to the ramp where the trains arrived. Occasionally there were things lying on the ramp left by people arriving in Auschwitz, so from time to time Pepik managed to pick something up. Once he, for example, found a small canister with warm goose fat, and he poured a bit into each of our cups.

In Auschwitz I also met Fischer the executioner, whose original occupation had been a butcher, who'd worked as the executioner in Terezin. In Auschwitz he worked as a capo [concentration camp inmate appointed by the SS to be in charge of a work gang]. Through Haindl, Fischer knew my brother Pepik. Once when I was returning from roll call I met him, right away he greeted me and asked how I was, and where in the camp I was working, and whether I didn't need anything. He promised that if I needed anything, I should come see him, and he'd arrange it. But I never went to see him.

For six months prisoners in the family camp had so-called 'Sonderbehandlung,' or 'special treatment' - families weren't split up, they for example didn't shave our hair off, and they isolated us in camp BIIb. However, 'Sonderbehandlung' was planned for only six months, followed by death in the gas chambers. The first transport was gassed without prior selection in the night from 8th to 9th of March 1944, on President Masaryk's birthday 10. Prisoners from the second transport were afraid that once six months after their arrival passed, they'd also be murdered. My cousin Inka had arrived on the second transport, she was afraid, and said that now it was their turn. However, the Nazis decided to not murder all of them, organized a selection, and picked some for the prisoners from the second and third transport for slave labor outside the camp.

I was in the FKL - 'Frauen-Konzentrationslager' [women's concentration camp] where they shaved our entire bodies, but left me my hair. We also went through several selections there. The conditions in the 'Frauen- Konzentrationslager' were horrible, tons of bedbugs. We'd for example go to the latrines, and as soon as we sat down, we'd be showered with cold water, being sprayed at us by Polish women, who were horrible. When we arrived in the FKL, my cousin Inka said that their transport would go to the gas for sure. But the Germans changed their minds, and decided that they'd rather use us for work. First the men left for work in Schwarzheide.

We went for a selection - the barracks had so-called chimneys in the middle, along which we had to walk and Mengele would be sitting there, and pointing, left, right. Mengele needed to pick out a thousand women. Older women and mothers with children remained in the camp, and the younger ones he picked. He'd picked out some women, but he was still missing a certain number of the thousand. My mother wasn't in the selection, because she was already 48, and seemed to be too old for them. However, when they still didn't have the required number of women, they ordered all women up to 48 to present themselves. Finally, Mengele also picked my mother for work.

We had to undergo a gynecological examination - though I was so skinny that there was no way anyone could've thought I was pregnant, so I avoided the exam. They sent us to go bathe, we were, of course, afraid that instead of water gas would come out of the showers, but in the end it really was water. When we went to go bathe, I was wearing an Omega wristwatch, and thought it would be a shame to damage it, so I said to myself that I'd hide it somewhere. A pile of coal caught my eye, so I hid it in there, intending to retrieve it after washing. But then we all exited out the other side, so I never saw the watch again.

We had to take everything off, and they told us that we'd pick our things up after washing. I had a silver ring with garnets, so I tied it to a shoelace and hid it in my shoes. But I never saw those shoes again, because they took everything from us. Instead of our own things, we were issued horrible rags, and high-heel shoes! So I then left for work in Hamburg in high-heel shoes! We also got a piece of bread and a piece of salami, so that we'd have something for the trip. I ate my ration right away, and my mother saved hers for me, in case I got hungry.

My brother left Auschwitz to go work in Schwarzheide. We ran to the end of the camp to watch them leave on the train. Because my dad was already 65, they didn't take him for work in Schwarzheide. When my mom and I left for Hamburg in July 1944, my dad stayed in Auschwitz. Saying goodbye to dad and Auntie Zofie from Nadejkov was awful, because I already suspected how it would end. Dad was calming me down, and said: 'I've got my life behind me, you've got yours ahead of you, I'm glad that you're going with Mom.' My father didn't survive; he went into the gas that same year, 1944. The worst thing is that my dad never believed in the gas. He said that it after all isn't possible for them to send young, healthy people into the gas. When they told me that they were burning people there, I cried terribly, and my dad kept telling me to not believe it, that it's not possible. I guess the poor man had to find out the hard way...

There were about fifty of us women in the wagon to Hamburg. It was July, sweltering, and we had one pail for a toilet and one pail with water. There were so many of us that I remember that in the evening it wasn't possible for all the women to lie down. Half of them always had to sit, and the other half could lie down. My mom ate a piece of salami and got horribly sick. She lay down, had a fever, and was lying all day. I remember that the women began complaining that my mom was lying down for too long. I told them that I was sitting that whole time, so that my mother was simply lying down instead of me.

My mom had a fever, and then sometime towards morning she got up, saying that she needed to use the toilet. I wanted to help her, that I'd support her, but she refused. The poor woman was so weak that she tipped the pail over. I was miserable; I didn't know how I was going to clean up that mess, the pail had spilled out into the entire wagon! The pails contents were all over the whole wagon, it was hot, and it stank.

At that moment we stopped. I went to see the SS post, we called them 'postmen,' and described to him what had happened and asked him if he wouldn't please lend me some sort of broom, so I could clean out the wagon. He told me to wait, returned in a bit, and gave me handfuls of tall grass he'd picked, with which I could scrub it clean. He was nice and helped me, and he was bringing me pails of clean water with which I always flushed it and cleaned it, scoured it with grass, and again and again until the wagon was clean. I asked my cousin Inka to help me. She refused. The only girl in the wagon that helped me was my friend Vera Liskova, who'd worked with me in the 'Landwirtschaft.' What with the sun blazing down and the heat, the floor was soon dry and was snow-white!

We arrived in Hamburg, at a place named Freihafen. It was an old granary, a ramp and train tracks. We didn't know what was to become of us, where they'd take us, nothing. I was afraid for my mother, that if she was ill they'd shoot her. I pleaded with Inka to help me with my mom, but she refused, that she wanted to go stay with some other girls. But then she probably thought about it some more, remembered that our parents had always helped her when her father had thrown her out of the house, and so stayed with us. We led my mom to the first floor, laid her down on a bunk, she got some sleep and the next day she was already feeling better. There were an awful lot of us living in one room, and the conditions were terrible.

The next day we didn't go to work yet. We got some sardines in tomato sauce that I ate with relish, they were excellent. In the morning we'd get black coffee and a little piece of bread. There were these troughs there where we would go wash up. From there we'd be transported to various plants like Eurotank and RTL, and for cleanup work, basically wherever we were needed. We cleared away bombed-out buildings, chipped the old mortar off of bricks and put them at the side of the road, because bricks cleaned up in this manner were then taken away for use in the construction of new buildings. One time some German came walking by, and told us that once we clear it away there and get to his cellar, where he's got potatoes, we should dig them up and that he'd give us some of them. We thanked him, and thought to ourselves that the poor guy has no idea that we'd already found and eaten them long ago.

We cleared the rubble of bombed out buildings, where for example only one wall had remained standing, and with it the remnants of toilets or larders. In the larders you could occasionally find food. We for example found pickled eggs in a jar, which on top of that had been cooked in the fire. The girls ate them, but I was afraid to.

I remember that we used to go wash in these troughs. Once my mother told me that she had the feeling that my friend Lotka was pregnant. I told her that I didn't think so, that Lotka hadn't mentioned anything like that, just that she occasionally complained that her stomach was growling, but she blamed it on the bad food in Hamburg. But my mother said that Lotka's stomach was beginning to show. I asked Lotka whether she wasn't pregnant. She didn't want to accept anything like that, but to be on the safe side went to see the doctor. She told her that she was in her fifth month of pregnancy. She'd gotten pregnant while still in Terezin, and had had absolutely no idea. After that she didn't go with us to do hard work, and helped peel potatoes in the kitchen.

However, after some time they sent her back to Auschwitz along with two other pregnant girls. Before she left, she told me that if they take her back to Auschwitz, she'd rather escape along the way than to return to Auschwitz to go into the gas. We never found out what happened to Lotka. No one managed to find out how and where she'd perished, all I know is that from Lotka's entire family, only her mother survived.

I remember that once we were carrying terribly heavy metal rods several meters long, which had to always be carried by three women - one in the front, another in the middle, and a third at the end. While we were doing it I started feeling terribly ill. I went to see the post and asked him if I could go sit down for a while, that I didn't feel well. He allowed it, so I sat down there.

In a while the main doctor came walking by, who we called 'senilak,' because he was an obnoxious old geezer, and was quite nasty. As soon as he noticed me, he bellowed that how did I dare just sit there like that. I told him that I'd asked the post if I could sit down, because I was feeling terribly ill, that I had a fever and sore throat. So he called me over, and ordered me to open my mouth and stick out my tongue. He asked me why I hadn't reported that I was sick first thing in the morning, so I told him that in the morning I'd felt fine. He told me to come with him. I was afraid of where he'd take me.

There was some sort of villa nearby, and he led me into the villa, into the cellar. The cellar was full of bottles; he took one bottle, poured out some of the contents and asked me whether I knew how to gargle. Maybe he thought that we were Neanderthals, that we didn't know what gargling was! He ordered me to gargle every so often, and upon arrival to report to the doctor in that ward.

We rode dump trucks to and from work, the most able always jumped on first, to grab places to sit around the walls. That day I felt terribly sick, and just stood there like a statue. By chance 'senilak' came walking by, and when he saw me standing there, he ordered the others to let me sit down.

When we returned, I reported to Dr. Goldova, who was an awfully swell lady, a Jewess, who was responsible for us. The doctor gave us a thermometer, with the words that whoever has the highest temperature would go first. I won, as I had over 40. Dr. Goldova looked inside my throat, and was appalled. She told me that I had diphtheria. She sent one SS soldier for serum, because they were afraid of the diphtheria spreading. Luckily he found some serum and I could get an injection. I lay on a bunk, lying beside me was a girl with scarlet fever, and across from me another one that was giving birth. She gave birth to a boy, who died after a week. Luckily, I've got to say, because if he wouldn't have died, they would have both perished.

So I lay there with diphtheria, I felt terrible, and couldn't eat. We were issued bread, so I hid it under my pillow, to eat once I felt better. But a rat ate the bread. Boy, were there a lot of rats there! This is because we lived in an old granary, where there were steel cables and wooden seals between the floors, and that's how the rats got in. I was always waving my arms and saying 'shoo, shoo.' Dr. Goldova asked me what I was always chasing away, whether it wasn't flies. I told her that it was rats, and she thought that I was hallucinating from the fever, she couldn't believe that there were rats there. I lay there for five days with diphtheria, and then I had to go work again.

Some people in Hamburg were very kind; I remember that once some German woman called out to me from some building, for me to come over to her. At first I was afraid to go into the building, but she handed me a loaf of bread and told me to split it with the girls. Another time a person came along and when he saw what kind of shoes we were working in, he brought over a wheelbarrow of shoes, for us to pick some more suitable ones from. Because in Auschwitz I'd been issued high-heel shoes, which really weren't suitable for work!

After one air raid that destroyed the buildings in which we'd been living, they transported us by train to another camp. During the train trip I got my first slap from an SS woman. Some of the girls that were there with us wanted to get on her good side, and so would do anything she wished. Because the SS woman wanted very much to learn to sing the song 'Prague Is Beautiful' in Czech, which for some reason she liked and was constantly wanting to sing it. It annoyed me the way she was constantly singing, and so I cracked something like 'stupid cow,' and right away got a good slap.

They took us to some train station. We had no idea where we were, and it was already twilight. Both my mother and I needed to use the toilet. We watched to see where the other girls were going, went after them, and as it was getting dark and you couldn't see properly, I suddenly fell from the ramp into this gully. I got some scrapes and bruises, but nothing serious happened to me. Then they led us on foot in the darkness, some girls could no longer go on, and stayed at the side of the road; I don't know what happened to them.

At dawn we arrived at the camp. It was still half-light; suddenly I glimpsed a huge dark mountain beside me. I looked more carefully, and realized that they were shoes. A huge mountain of shoes... We'd arrived in Bergen-Belsen.

The conditions in Bergen-Belsen were catastrophic. They put us up in some building, where we met up with the girls that had arrived from Christianstadt a little earlier. I don't remember anymore if there were mattresses there, but I think that there was only straw, we laid on the floor like sardines next to each other. The conditions were terrible, truly horrible. There was almost no food, getting even a little bit to eat was terribly difficult, the accommodations were atrocious. There was no water, we couldn't wash, the toilets were atrocious. Because there weren't enough toilets for so many people, the men dug out these deep ditches where people used to go, there you saw men's, women's bottoms, and you didn't give a damn.

Post-war

We were still in Bergen-Belsen when we were liberated on 15th April 1945. The English were driving by and blaring in all languages that we'd been liberated, but that we have to wait for quarantine and for orders. When it was already clear that the Allied army was approaching, a lot of the SS ran away. But some of them stayed, and those were ordered by the English to run around in circles, like they used to order us to do earlier.

After liberation the English distributed canned pork. My mother confiscated it from me, told me that we won't eat that, and allowed me to eat only crackers and powdered milk. Many girls ate from the cans and got dysentery. After the liberation we went to go have a look around the camp, we for example discovered a building full of prosthetic limbs, there were artificial arms and legs lying around everywhere, elsewhere there were buildings full of glasses, or of clothes. There were bundles of skirts, dresses and shirts lying around. In another place I found an office full of money from all sorts of countries, but it didn't even occur to me to take some of it, because I didn't know what I'd do with it in Bergen-Belsen. For me, clothing and a bite of food were of more value than money.

In Bergen-Belsen, I saw so many horrors, piles of corpses, skin-covered skeletons... After liberation the Germans were forced to load the prisoners' corpses onto a flatbed truck with their bare hands and haul them away. A girlfriend of mine didn't have shoes, so she approached one English soldier and asked him if he couldn't find some for her - he ordered one SS woman to take her shoes off and give them to her. As my friend was completely barefoot, he ordered the SS woman to give her socks to her as well.

Imagine that there were loads of blueberries in Bergen-Belsen. I loved picking blueberries, so after we were liberated I kept going to pick berries. I exchanged them with the girls for cigarettes that we used to get in Red Cross packages. I didn't smoke, but was hiding them for my brother, from whom I'd gotten a letter that he'd survived. I got three cigarettes for a liter of blueberries - and in the end I managed to bring my brother 1500 of them! Boy, that was a lot of blueberries, my brother's eyes bugged out when I brought him 1500 cigarettes. Because after the war, American cigarettes were worth a fortune.

I looked for my friend Regina, who'd come to Bergen-Belsen from Christianstadt; we knew each other from Terezin, where we'd worked together in the staff garden. I found her, too, she was ill and had terribly swollen legs. She asked me if I couldn't please pick the lice from her hair, the poor thing's head was full of them. At that time I didn't suspect that she also had body lice, which I, of course, caught from her. My mother didn't catch anything, as all day she sat there, turning clothes all 'round and inside out, looking for lice, so that she wouldn't get infected.

In the infirmary, some girls told me that they were terribly thirsty, whether I wouldn't bring them a bit of water. I went to have a look around, and found this bathing pool from which I wanted to scoop up some water, so that the girls could also wash themselves. But suddenly I noticed that there were bloated corpses swimming in the pool...

In Bergen-Belsen I had a friend, Lucka Brilova, the two of us walked all around the surrounding area, looked at abandoned houses and thought about what they might contain. Once we found a house in which there was this large workbench, it had apparently once belonged to some watchmaker or jeweler, because there were tools lying all over the place. We were walking through the garden where there was a well, we stopped there, and I found a wristwatch. I took it and we were returning in the direction of the camp. On the way we met my mother, who had gone out to meet me. My mother was collecting cigarette butts which were lying around everywhere from the soldiers; she was emptying the tobacco out of them and collecting it in a box.

We met a Russian carrying a slaughtered hen. My mother asked him if he wouldn't sell us the hen. He wanted to know what we could offer him for it. So we showed him the watch and tobacco. He wasn't too interested in the tobacco, saying that it wasn't good, but we talked him into taking the tobacco and 'the time,' and got a good hen. My mother made soup, and she even scrounged up something for dumplings and made some sauce. But I was already beginning to feel ill and wasn't able to eat anything, so my mother pleaded with me to at least eat a couple of spoonfuls of soup. As it turned out, I'd caught typhus from Regina.

I was lying there, and a German doctor came to see me, who was originally from somewhere by Karlovy Vary 11. The problem was that there wasn't any medicine. So naked, just wrapped in a blanket, they loaded me onto some plank and carried me to a hospital, where I laid on the ground, just in that blanket. I don't remember much of it, I was terribly ill, with fevers in the forties, and was completely apathetic; all I know is that German women were washing us. We had to be weighed, I weighed about 42 kilos, but that was at a time when I was already downright 'fat;' before that I'd weighed quite a bit less.

Gradually I got better, and my fever declined. So they sent me across the way to some building, that there they'd issue me a shirt. I arrived there wrapped in just a blanket, I could barely walk, and had to walk hunched over, otherwise I wouldn't have managed to remain standing. I got a piece of cloth, which someone sewed together as I held it, so I was wearing a sack with two holes, this being my nightshirt. Some woman in a uniform was giving me the cloth, and I was saying to myself that this woman seemed terribly familiar to me, but I couldn't remember where I knew her from. I kept having to think about where I could know her from, as she seemed terribly familiar to me! It wasn't until after the war that I read that Marlene Dietrich had been accompanying that army, so I think that it was she. [Dietrich, Marlene (1901 - 1992): German-born American actress and singer]

When I got better, I looked for Regina, who was still ill. When my mother and I found her, Regina had only one wish - she wanted sauerkraut. We managed to find it for her in some kitchen. She was so happy! After her serious illness, Regina got an offer to go to Sweden to recuperate, and was told she could take family members as well. She was an orphan, so she wrote that I was her sister, and that Mom was her mother, so that we'd go with her.

The trip to Sweden didn't take place, however, because in the meantime we'd received a letter from my brother, that he'd survived and was already in Prague. So Regina left on her own; later she wrote me that a distant aunt was inviting her to America, and she didn't know whether or not she should go. Regina was originally from an orphanage in Prague, so I wrote her to go and see her aunt in America, that she could come back to Prague whenever she wanted if she didn't like it in America. In the end she settled in America, I've already been there twice to see her.

My mother and I left Bergen-Belsen for home in July 1945. We traveled several days by train, roundabout through Sumava and Pilsen to Prague. Traveling in the compartment with us was my friend Lucka Brilova, who was originally from Teplice, which before the war had been a region where Germans lived. Lucka spoke Czech very poorly, because she'd attended German schools. I remember that Lucka telling me in the train to quickly teach her 'Kde domov muj?' [Where is My Home?] This was because we had decided that we were going to sing the Czechoslovak national anthem when we reached the border.

My mother and I arrived at the Smichov train station. We had a couple of bags, a large bag of crackers and some things we'd received in packages from the Red Cross. So from the train station we called our neighbor from Moran, Liska the confectioner, with whom we'd hidden the cart that my parents had used to transport goods to the general store before the war. Mr. Liska came to Smichov to get us. I remember that I was wearing some drop-front sailor pants and wooden shoes, nothing else - there wasn't any clothing.

When we were arriving in Moran, people were staring at us, and everyone was shouting something at us. Mrs. Schneiderova called out 'Liduska, your typewriter is at our place!' Everyone in Moran was terribly kind to us. Our neighbor on the first floor offered that Mom, Pepik and I could live with her. This was because we had no place to live, as the two rooms that we used to have before the war behind the store were occupied. She owed us a lot, so she subtracted it from the debt. Then the brother of my former school principal rented us a room with a kitchen, because he was in the hospital.

Pepik was already in Prague; he'd returned from Schwarzheide on a death march 12. He was telling us about how they'd been walking through a field, and because he was hungry he'd bent down for a potato he'd seen on the ground. An SS soldier leading them along saw that, and came and stepped on his hand. Because he'd already had a hangnail on that hand, it became infected. When they arrived in Terezin, Pepik already had fevers and was in general in a bad way. They put him in the infirmary and told him that they'd have to amputate the hand, as he had gangrene. But Pepik objected, that without his hand he wouldn't be able to live and work, because he was an auto mechanic. He threatened them that if they were going to want to cut off his hand, he'd jump out the window. Finally some medic helped him, they managed to localize the gangrene to only the tip of his finger, and so in the end they only cut it off at the last joint.

After the war, after liberation, our friend Vlasta from Moran, where we lived, set out with her cousin Jirina for Terezin to look for us, they didn't have any news of us, and were hoping to find us there. They described to me how they arrived at the infirmary and all the guys were staring at them, as they were very pretty girls. Pepik recognized them, but apparently they walked right by him and didn't notice him at all. So Pepik called out: 'Vlasta!' Vlasta turned around, went over to him and said, 'What would you like?' Pepik said to her: 'Hey, it's me, Pepik!' They didn't recognize him at all; he was in a terribly pitiful state. Vlasta told me that he looked like his own grandfather.

Of our entire family, only I, my mother, brother, my cousin Inka and one distant cousin from Jindrichuv Hradec survived. After the war, when I returned from the camps, I had no documents. Back then I wrote the Community, for them to send me a copy of my birth certificate. From the Community they wrote me back that no Ludmila Weinerova had ever been born in Prague. You see, after I'd had myself baptized in 1939, they deleted me from the Community. So I wrote Father Culik in Nizebohy, who'd baptized me before the war. He sent me all my records right away, and sent me a very beautiful, nice letter, how happy he was that I survived the war.

After the war I lived for a couple of months in Kytlice, near Ceska Lipa, where my friend Hanka was in charge of a factory that made moldings and frames. We lived in a gamekeeper's lodge; we had a kitchen and two rooms there. The gamekeeper and his wife and son were Germans who were waiting to be deported 13. They were very kind people; Hanka and I used to go visit the gamekeeper's wife for lunch, and would give her our food vouchers. So in Kytlice we ran a molding and frame factory, Hanka would visit glaziers, painters and grinders, and design various products, for example decorated trays, or napkin holders or moldings that we then offered to various companies. I took care of the administration and paid the workers their wages.

There were only 16 of us Czechs in Kytlice, and when political parties had to be founded, we divided ourselves into four groups - four of us were Communists, four social democrats, for national socialists and four in the People's Party [Christian Democrats]. Hanka and I had no idea who we should join, until we finally decided to join the social democrats. But I was never very interested in politics. But after about a half year, the company was wound down and all the machines that were there were being sent to Slovakia. At that time I told Hanka that it seemed that she'd no longer be needing me, and that I was going to return to Prague, where my mother was already looking forward to seeing me. In Prague I found work right away, at Autogen O. Mares, on Petrske namesti [Peter Square].

In Prague I met my future husband, Karel Rutar. Life is full of coincidences; Karel was actually almost the first man that I saw in Terezin! But I barely knew him; I'd seen him only in passing and didn't pay any attention to him at all. You see, in the beginning in Terezin we were staying with some family named Polak. Once Mrs. Polak said that their niece Hana and her husband Karel were coming to visit them. When I saw them, I remember being taken aback that they were married, because they were awfully young. The way it went back then was that people tried to get married before the transport, so that they could live together. I didn't pay any particular heed to Karel in Terezin, all I knew was that he'd then gone to work in Wulkov - he was quite handy, and had worked as a carpenter in Terezin.

After the war I found out that he'd been the head carpenter, and that some problem had happened there that he didn't cause, but they punished him for being the boss and letting it happen. The SS soldier punished him by making him go outside at night, in the winter, naked, and pouring cold water on him. He then gave him such a slap that it punctured his eardrum, and for the rest of his life Karel was hard of hearing in one ear. From Wulkov he returned to Terezin, where after the war he recuperated, and then brought with him to Prague many materials - correspondence cards, on which you could send a maximum of thirty words to Terezin, maps, and a picture painted for him by the caricaturist Haas, brother of the actor Hugo Haas. [Haas, Hugo (1901 - 1968): Czech actor of Jewish origin, belonging to among the most significant personalities of modern Czech theater and film.] His wife Hanka and I had worked in the 'Landwirtschaft' together, although she then got typhus, so then no longer came to work. Karel's sister Ela and his mother were murdered in Auschwitz.

As I say, they're all big coincidences - after the war, Karel's aunt, Mrs. Helena Schwarzova, got remarried, to some Mr. Schütz from Pardubice who made matzot, she was a very good friend of my mother's and absolved Terezin, Auschwitz, Hamburg and Bergen-Belsen with us. Mr. Schwarzova had two sons, Zdenek and Viktor, and tried to put me together with Zdenek; poor Zdenek never returned from the concentration camps.

So one time, after the war, in 1946, Mrs. Schwarzova came over to see my mother and was telling her that her nephew Karel would like to get his motorcycle license, and whether Pepik couldn't help him with it. So Karel came over for a visit, we talked a bit, and in return he invited us to his apartment in Vrsovice, where [Karel's] Aunt Schwarzova baked a cake and made coffee. When I was there, I saw a photo of Hanka in a frame. I told him that I knew that girl, that we'd worked together in Terezin. And he said that it was his ex-wife. You see, Hanka had gotten together in Terezin with this one Dane. Karel gave her a dowry and arranged everything for her; he outfitted her to be a bride.

Karel and I were married in 1946, and I moved in with him, to his place in Vrsovice, where I live to this day. In 1947 we had a daughter, Iva, and at first I was at home with her. Then my mother babysat her for some time, when I went to do office work for the Teply Company. After the war we weren't well off, so my husband and I both worked. I had an excellent salary; I worked as a payroll accountant and head cashier, and at the same time also hired laborers and clerks. In 1949 our son Josef was born. Then I found a job at Sazka, where I worked three days a week, so my salary would at least cover the rent. Karel worked for the Milk and Fats Association, then transferred to the Ministry of Food Industries, and then went to work as a clerk for Orionka [The Orion Chocolate Co.].

My mother died in 1964; in her old age she suffered from advanced Alzheimer's disease. My husband died in 1966 at the age of 49, of leukemia. I was left alone with two children. In 1968 my brother Pepik immigrated with his family to America, where he died in 2005.

My brother's emigration caused me problems at work - up until then I had been working for Cedok and I used to go to Romania on business. [Cedok: a travel agency, founded in 1920, with headquarters in Prague. Its name is an acronym taken from the name "Ceskoslovenska dopravni kancelar" - Czechoslovak Transport Agency.] After Pepik emigrated, I was no longer allowed to travel outside of the country on business. They confiscated my work passport. I was allowed to visit the countries of the socialist bloc as a tourist on my personal passport. I didn't make it over to visit him until I was retired, in 1976 and then again in 1987. As a retiree I was allowed to go to America, because the Communists would have liked to get rid of retirees. I remember that I was amazed at how many goods were available in America; back then in Czechoslovakia there was almost nothing, so for me it was a tremendous contrast. But I have to say that I never considered emigrating.

When the children were small, I decided to have the number tattooed on my forearm removed. Circumstances forced me into it. I used to often take the train to our cottage with my children. In the summer, when I'd be wearing a short-sleeved dress, I'd often notice people looking at my forearm, and then whisper amongst each other. It used to happen that they'd turn to me and begin to feel terribly sorry for me, and keep repeating what a poor thing I was, how I must have suffered during the war. I don't want anyone's pity. And it definitely wasn't at all pleasant for someone to tell me what a poor wretch I must be.

So I decided that I'd go to the doctor and have the number removed. I arrived at the dermatology ward, and the lady doctor asked me what was ailing me. I told her that I'd like to have a tattoo removed. She looked at me with an annoyed expression and began berating me: 'And why did you get a tattoo in the first place? You could have realized that one day you'll change your mind, and now all you're doing is making more work for me!' So I told her that I hadn't exactly been overly enthused about getting this tattoo, and if I'd have had a choice, I would definitely have not let them give me a tattoo. Then I rolled up my sleeve. The doctor immediately did an about-turn and began to apologize profusely; the poor thing had had no idea of what sort of tattoo it was.

After the war I was in Auschwitz with my son to have a look; there are only chimneys left behind. I wanted to show my son camp BIIb (Auschwitz II-Birkenau), where I'd lived. I showed him the latrines, and told him that I had to throw away a diamond broach into them. My father had given it to me back then, so that I'd have something with me for the trip to Hamburg to work as a keepsake. I'd have had to give it away to the Germans, which I definitely didn't want to do, so I preferred to throw it away into the latrine, rather than have the Nazis end up with it! Since the war I've been in Auschwitz only once. Occasionally I participated in Holocaust remembrances, and to this day I attend events put on by the Terezin Initiative 14.