Bella Kisselgof

Bella Kisselgof

Novorossiysk

Ukraine

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Family background

Growing up

During the War

After the War

I was born in Enakievo in the Donetsk region of Ukraine on May 14, 1936. My father's name was Grigory Kisselgof. He was born in the village of Novo-Vitebsk in the province of Ekaterinoslav (Dnepropetrovsk region) in 1903. My mother Sofia Rivkina was born on October 10, 1906 in the same village. Several generations of my ancestors lived in Novo-Vitebsk.

Novo-Vitebsk is an old Jewish colony founded during the reign of Empress Ekaterina II (1729 - 1796). At her order several Jewish colonies were founded around Ekaterinoslav. The Jewish population of these colonies was basically involved in farming. There were handicraftsmen, merchants and teachers, but farmers constituted the majority. People moved into tiny and comfortable houses with facilities that were built specifically for them. These estates were inherited by the following generations. There was a synagogue in the central square in each little town. The population spoke Yiddish and the official documentation in the town houses was issued in Yiddish.

My father finished the eighth grade at a secondary school in Novo-Vitebsk. He didn't have any professional education. My father was intelligent and had good organizational skills. I know very little about the family of my father Grigory (Gersh) Kisselgof. In 1941, at the beginning of the war, he went to fight at the front and perished. While he was still with us I was too young to show any interest in the family history. After he died his family terminated any relationships with my mother. My mother tried to avoid any talk on the subject of his family. So, I don't even know the name of my father's mother. My grandfather's name was Mordko, and later he was called Mark. I also know that my father had a brother named Lyova and a sister named Dvoira.

I know much more about my mother's family. My grandmother told me a lot about her parents. I have photos of my great-grandparents. My great-grandfather's name was Gedalia Dreitser. He was born in the late 1830s. His parents lived in Novo-Vitebsk. He was the youngest of his many sisters and brothers, but I don't know how many children were in their family. When Gedalia reached the age of 18, he went into the tsarist army as a private. The term of service was 25 years. Whetn it was his time to retire he got a house with furniture and all utilities built in Novo-Vitebsk for him, all paid for by the tsarist treasury. It was a usual thing at that time. The soldiers retired when they were about 43 years old and they were to start their life anew. And the tsarist government made all necessary provisions for them to begin their civil life. They could choose where they wanted to settle down. My great-grandfather chose Novo-Vitebsk to be near his family. After he came to Novo-Vitebsk he married a young girl named Bruha. I don't know any details about how they met or about their wedding. They started having children almost every year or every year and a half. The oldest was their daughter Haislova, born in 1875. Then there was another daughter born in 1877. My grandmother Riva was born in 1878, and in 1879 their daughter Luba (Liebe) was born. The youngest was Sonia, born in 1881.

My great-grandmother Bruha Dreitser was born in Novo-Vitebsk in the 1850s. She was the youngest daughter in a very poor family. From childhood she had to work hard. She was so eager to study. My grandmother told me that when her older brothers were doing their homework - they studied at cheder - she was fussing around them trying to understand what they were talking about or reading. She learned her ABCs and some mathematics in this way. My grandmother recalled that after Bruha finished with her house chores she took a book in Yiddish or Hebrew to read. It was the best pastime for her. Her daughters had a teacher at home and their mother helped them to do their homework. She was known in the town as an intelligent and wise woman. People often asked her advice. She knew everything - why a fruit tree gave no fruit, or how to cure a sick child, and how to get more milk from a cow. People often tried to give her some money for her advice but she never accepted any. If they gave her a present she accepted it, but always gave something in return. According to the Jewish traditions a woman couldn't be an arbitrator, but people elected my great- grandmother as a member of the town arbitrary court several times. She was loved and respected. My grandmother told me that when my great- grandmother Bruhashe died in 1921 the whole population of the town came to her funeral, and they said that life would be more difficult without Bruha.

My great-grandfather Gedalia Dreitser and great-grandmother Bruha Dreitser were religious people. They taught their daughters to respect the Jewish religion and traditions. Gedalia and Bruha went to the synagogue on Saturdays. They always met Sabbath and my great- grandmother lit candles. They celebrated Jewish holidays and my great- grandmother strictly followed the rules for a kosher kitchen. My grandmother Riva learned from her to cook traditional Jewish food and taught my mother all her skills. When my mother was cooking, she always mentioned that it was how her mother used to do it. My mother told me that the whole family got together in the house of Gedalia and Bruha at Pesach. My mother didn't remember many details, but she always told me about the beautiful dishes and delicious food and sais that my great-grandmother was always happy that all her children followed the tradition of getting together at their parents' home.

The family lived well. The ex-soldiers who had excellent service performance records were paid a good monthly pension. This was a sufficient amount of money and my great-grandfather could just stay at home, but he couldn't help working. He became a carpenter and he always had many orders. My great- grandmother was a housewife. They had an orchard and a vegetable garden and my great-grandmother kept chickens and sold chicken meat and eggs. They spoke Yiddish at home. Besides receiving a pension, my great-grandfather also had the right of free education for his children. But there was no school in the town and all his daughters got a religious education at home. Later, they all studied in the Russian grammar school in Ekaterinoslav (Dnepropetrovsk). They lived in the hostel of that grammar school. The girls studied well. They were exempted from attending Christian classes. Senior school children had dressmaking classes and my grandmother Riva was proficient in this skill. Later she made clothes for the whole family.

All of the girls married. I don't remember their husbands' names, unfortunately. Haislova married a teacher. They had three children. She died after the war, in the 1960s. Another sister of my grandmother and her husband left for America. I don't know her name and we have no further information about them. Luba's husband was a timber dealer. They had two sons. I know that Luba survived during the war, but I remember no details about her life. I don't remember much about Sonia either. She was married to a doctor. Her husband perished on the front during WWI. Sonia married a second time and that is all I know about her. My great-grandfather, Gedalia Dreitser, died in 1917. He and my grandmother Bruha were buried at the Jewish cemetery in Novo- Vitebsk.

My maternal grandmother Riva Dreitser-Rivkina returned to her parents in Novo-Vitebsk after finishing grammar school. In 1898 she married my maternal grandfather Shymon Rivkin from Novo-Vitebsk. They had a traditional Jewish wedding with the rabbi and the chuppah. The party lasted three days in the yard of Gedalia's house. All the inhabitants of the town were guests. Klezmers from Ekaterinoslav played for three days. After the wedding the newlyweds lived with their parents for about two years until they moved into their own house built by grandfather. It was a wooden house with all necessary utility buildings in the yard. There were three rooms, a closet and a kitchen in the house. There was also a plot of land with two apple trees and a few raspberry and black currant bushes. There was also a well in the yard.

My grandfather Shymon Rivkin was born in 1870. I know little about his family. He had a few brothers. At age thirteen, the boys were to study a profession. After my grandfather had his bar mitzvah, his father offered him a choice of three professions - shoemaker, tailor or blacksmith. My grandfather chose the profession of blacksmith. He was an apprentice at first, and then an assistant until he became a very good blacksmith. When he started earning enough money to provide for the family he married my grandmother Riva.

After they got married my grandmother was a housewife. My grandparents were religious people. They led a traditional Jewish way of life. On Fridays they went to the synagogue and my grandmother lit candles at home. They celebrated Jewish holidays in the family. I don't know the details, but I believe my grandmother prepared for the holidays as thoroughly as her mother Bruha. I remember my grandmother's gomentashes, little triangle pies with poppy seeds that my grandmother made for Purim. This was in Enakievo when she visited us. I remember my grandfather praying when he was visiting us in Enakievo. I had to leave the room, but I could look through the doorway to see how he put on his thales and tefillin to say his prayers.

Their first son was born in 1900. I don't know his name. Mama never talked about him. When he was thirteen he fell onto the cement floor at cheder while playing with other boys and died from concussion a few days later. In 1902 their daughter Luba was born, and then their son Grisha in 1903. In 1906 my mother Sofia was born. In 1907 their son Misha was born, and in 1917 Foya (Efim), the last child in the family, was born.

Tthe oldest son - the boy that died - and Grisha went to cheder. After the revolution in 1917 a secondary school was opened in Novo- Vitebsk and all the children studied there. All members of the family spoke in Yiddish but they all knew Russian. Novo-Vitebsk did not suffer from pogroms. In the 1920s there were many anti-Semitic gangs in Ukraine. They killed Jews, robbed and burned their houses, raped women and killed children. My mother told me that various gangs were there, but there were no murders. They might whip somebody while galloping on their horse, but there were no robberies or killings. Nobody in our family suffered from such crimes.

The revolution of 1917 did not affect our way of life in Novo- Vitebsk. There were only two changes - they opened an 8-year secondary school, and started issuing all documentation in Russian. However, the stamps in the village council were printed in Yiddish.

My mother and her brothers were enthusiastic about the revolution. My grandparents were more skeptical about it, although their family was not that wealthy. My grandfather's earnings were enough only to buy the most necessary things for the family. My grandmother was a wonderful cook. She managed to keep the family well- fed and well-dressed for relatively small amounts of money. She made our clothes from the same fabric, but of different design. There is a family photo where all the clothes the family members are wearing were made by my grandmother.

In the 1920s the young men in the Rivkin family got bored with the dull life of a small Jewish town, and before the late 1920s they all moved to Gorlovka, a mining town in Donbass. By that time Luba and my mother were both married in Novo-Vitebsk. They had no wedding parties. The young people were rejecting Jewish traditions in beginning a new life. Civil marriages were popular at that time, and weddings were considered a bourgeois vestige. My grandparents were very unhappy that their daughter rejected the Jewish traditions, but they had to accept her decision, and they got along well with their sons-in-law.

My Aunt Luba married Aron Dolzhansky, an engineer. Luba was a housewife. They had two children: Ziama, born in 1923, and Mosia (Mihail), born in 1925. When the Great Patriotic War began, Luba's husband and sons went to the front. Aron was summoned from Gorlovka to the war at the very beginning, and Ziama and Mosia were summoned from Fergana when we were there in the evacuation. Ziama went at the end of 1941, and Mosia went to the front in 1943 when he was 17. He went as far as Berlin and when the war was over he was only 20. Mosia returned home after demobilization from the army in 1946. He passed exams for the 10th form of secondary school. He was very intelligent. He was educated at the Kharkov Engineering and Construction Institute and stayed to work in Kharkov afterwards. He got married there and had two sons. When he was 40, he drowned in the Donets River while swimming. His children live in Donetsk, but we do not keep in touch with each other.

Ziama's profession was the military. He studied at the Commandment Military College and as a military professional, moved from one town to another. He got an assignment in Lvov, settled down there, and retired with the rank of colonel. In the late 1970s, Ziama, his wife and their son moved to Israel. Ziama had a heart problem and couldn't get used to the climate there. He died soon after the move.

Luba and Aron settled down in Gorlovka after the war. My grandmother and grandfather lived with them. Luba died in 1978. Aron died some time before her.

Grisha lived in Gorlovka after the war, and worked at the mine headquarters. He married a Russian girl. At that time, after the revolution, nationality didn't matter to young people. All were Soviet people and internationalists. Uncle Grisha and his wife had a son. Uncle Grisha perished at the front in 1943. He served at the Stalingrad front with my father and that is all we know about him. My grandfather and grandmother got along well with their daughter-in-law, at least, on the surface. They also welcomed Misha's Russian wife. Uncle Misha also lived in Gorlovka before the war. He worked at the production association. He married at age 18, and his wife at 16. My mother told me the story of his marriage. Mama had a friend named Elena, a Russian girl. Misha was renting a room in Gorlovka then. He saw Lena where Mama lived, took her by the hand and they went to his home and started living together. There was no national issue in Donbass, the miners' region. They lived in a civil marriage. In 1936 Yury, their first son, was born. Misha was at the front during the war. After he returned they had another son, Victor. When it was time for the boy to go to school, Misha and Elena got officially married. Misha worked at the association and did some commerce. He died in 1982.

My mother's youngest brother Foya (Efim), finished tank school in Dnepropetrovsk in 1939. He was immediately summoned to the army and participated in the war wit Finland. After the Finnish war he served at the Great Patriotic War and then at the war with Japan. He fought in the wars for eight years. After the war he settled down in Chernovtsy and married a Jewish woman named Etia. After three years he and his wife moved to Lvov where he worked as a cab driver. He divorced his wife to marry a woman who was twenty-two years younger. They had a son. After my uncle died in 1990, his wife and son emigrated to Israel.

At first, my grandparents visited their children in Gorlovka and Enakievo. In 1932 they moved in with Luba and Aron in Gorlovka.

My parents didn't stay long in Gorlovka. They lived in a huge wooden barracks with many rooms on both sides of a long corridor. Mama worked as a typist and at the Department of Mines and my father had logistics work. They got along well with their Russian and Ukrainian neighbors. Soon my parents moved from Gorlovka to Enakievo. Mama was a housewife, and Papa worked at the headquarters of the mine "Red Profintern" located in Verovka in the outskirts of Enakievo. I was born in 1936.

Our family lived in a small, shabby wooden house at 139 Partisanskaya Street. We shared this house with another family that occupied half of the house. There was a summer kitchen and a well in the yard. There was a corner stove in this summer kitchen. Later I remember the same stove in our house in Chernovtsy after the war.

This other family was Jewish. There was a woman named Etia and her husband, and they had a son named Mosia. Etia became my mother's friend. Mosia was a hooligan of a boy and he didn't like me because I was a girl. Once my mother left me at Etia's care. She was busy with something and wasn't paying attention to us. Mosia took advantage of this situation and tarred my head. I had long hair and it took Mama and Etia a long time to wash this tar off my hair. Another time Mosia decided to check what was inside an eye and stuck a nail into my eye. Mama had to take me to the clinic. Fortunately, they saved my eye.

My grandparents' visits were a holiday for me. Sometimes they brought my cousin Yura with them. We were the same age and played together. We spoke Russian in the house. My parents switched to Yiddish only when they wanted to keep something a secret from me. During my grandparents' visits the adults communicated in Yiddish and spoke Russian to the children. After the revolution my parents became atheists. We didn't celebrate holidays or observe Jewish traditions in the house. I was also raised an atheist and an internationalist. Such was our era.

Mama told me there was no anti-Semitism in Donbass. One never heard the word "zhyd." Mama said that if it even occurred to somebody to say this word--and it might have been only a drunken person--he would be taken to the militia at once. I don't know whether there were many Jews in Enakievo at that time. I was five when we left during the war and was too young to give a thought to such things. But I know for sure that there were not many of them after the war. There was no synagogue in Enakievo or Gorlovka. Mama didn't tell me anything about the famine of 1931-33. (Editor's note: The artificially arranged famine in Ukraine in 1920 took away millions of people. It was arranged by Stalin to suppress the protesting peasants who didn't want to join collective farms. 1930-1934 - the years of dreadful forced famine in Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from farmers. People were dying in the streets; whole villages were passing away. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious farmers who didn't want to accept the Soviet power and join the collective farms.) I don't think the famine ever reached Donbass. This region of miners had good food products and supplies available.

The Repression of 1937 and the following years didn't touch upon our family. Mama told me that at that time a person could go to bed in the evening never knowing whether he would wake up in his bed. The authorities even arrested common people. Our neighbor, a tailor, was arrested for speaking out some careless word.

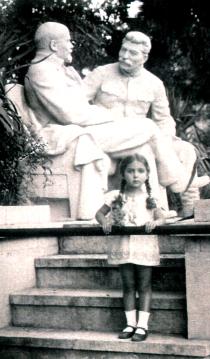

I know about the pre-war years from what Mama used to tell me. Mama said that even when Hitler came to power in Germany, nobody believed that he would enter into a war against the USSR. State propaganda convinced people that the country was so strong, it wouldn't occur to anybody to attack us. If it ever happened, we would win a prompt victory and defeat our enemy. Adults and children believed this. Children were raised with patriotic feelings. I didn't go to kindergarten, but I knew from my childhood that besides my family, I had two other grandfathers - Granddaddy Lenin and Granddaddy Stalin. Mama taught me patriotic poems. I remember one: "I'm a little girl dancing and singing, I've never seen Stalin, but I love him."

I have clear memories of the first day of the war. Germans began bombing Donbass almost immediately. It was of strategic interest to them, being the center of the USSR coal industry. The war began on Sunday morning, June 22, 1941. (Editor's note: On June 22, 1941 at 5 o'clock in the morning fascist Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring a war. On this day the Great patriotic War began.) It was a warm day, and my mother was taking a bath in our summer kitchen in the yard. When the bombs were falling she ran out of there covered in soapsuds. The bombings never stopped. We lived across the street from the metallurgical plant which was constantly bombed. The bombing was frightening. Then bomb-proof shelters were constructed, and people hid there during the air raids. People began to panic. Nobody knew what was going on.

My father and uncles were summoned to the front in the first few days of the war. Mama and I moved to Gorlovka - it was too terrifying to stay in Enakievo. My grandfather Shymon and Luba's sons were the only men with us. We went to the station to board a train. People at the station were boarding open railroad cars loaded with wheat. So, we traveled on this wheat. We were bombed the whole time. We crossed the Caspian Sea on a boat and ended up in Krasnovodsk. I was seasick on the boat. Then we went on to Fergana in the Uzbek SSR (Uzbekistan). At first we lived in a covered wagon in Beshbala on the outskirts of Fergana. Later we moved to a rented room in Fergana.

I remember going to the post office every day to check whether there was any mail for us. I was a little girl and they recognized me at the post office and gave me all our family's letters. Papa's letters were rare and he perished in 1943. Mama wanted to send a photograph of us to Papa, but we didn't know the number of his field mail. We kept the photo and Mama used to say that we would send it soon. In 1943 after the battle of Stalingrad we received notification that my father had been killed.

Ziama was summoned to the front from Fergana at the end of 1941, and Misha in 1943. Mama and grandmother worked at home for a shop. They knitted socks and gloves to send to the front. Once a week they took their ready products to the shop and received yarn for the next order. Luba didn't work. As the wife of a military man she received a provision certificate from her husband Aron. We shared one room. My grandfather was 71 before the beginning of the war, but nevertheless, he took a job as a blacksmith. Later he was taken to the mercury mine in the vicinity of Fergana. He was a provider for the family. Food supplies were very good there and they could receive food in exchange for their cards instead of money. Grandfather sent us flour, cereals and other food products. My grandmother was trying to feed the whole family, but there was still not enough food.

I went to the 1st grade when I was in the evacuation. It was a Russian school. I hardly have any school memories. I remember a Tatar girl that I shared my desk with. There were many evacuated children from all the towns. I didn't know their nationality - it was of no interest to me. I remember that my first teacher came from Leningrad. I finished the third grad in Fergana.

Mama had hardly any food at all during the war. We didn't have meat or even common food products. We had cereals and flour but Mama was leaving all the food we had for me. I remember Mama boiled potatoes and gave them to me to eat. She drank the water from the boiled potatoes. We survived due to the fruit in Fergana. Grapes were inexpensive. Mama used to buy a kilo of grapes and this was our lunch. Another good thing was that the weather was warm. There were aryks in the town and children used to swim in them. Mama was very afraid that I might drown. But I learned to swim there. Another memory is scary. There were rumors in the town that children were kidnapped to be turned into soap. Once I was kidnapped. My mother and grandmother were busy with knitting and I was outside playing with other kids. A Zoo was on tour in Fergana. It was fenced, and we kids were looking through the holes. A woman approached me asking whether I wanted to go inside. I agreed. She promised to buy me some apples, took me by my hand and we went on. Mama often told me that I shouldn't go away with strangers, but this woman was nice and I was eager to go to the Zoo. And I wanted apples, as we were always starving. We walked for a long time until we reached a street with many steel doors around. The woman knocked and knocked but nobody opened the door and she left me there. I can't remember how I got home, but I know that Mama was crying for a long time when I told her about it.

I remember Victory Day, May 8, 1945. People in the streets were crying, laughing and kissing. There were fireworks in the evening, the first fireworks I had ever seen in my life. I didn't understand why Mama was crying when everybody around was laughing. Mama was thinking about Papa . . . .

The war was over and we had to think about going back home. Mama was so weak that she couldn't walk. My grandmother was afraid that our trip back might be too much for Mama. In 1946 my mother's brother Foya came to pick us up. He was still in the army then, but he got a vacation to move us to Donbass. He was the only one to help us. Papa and Grisha were gone and Misha, Aron and Luba's sons were still in the army. Uncle Foya took us all - my grandmother, grandfather, Aunt Luba, mama and me, and we all went back to Donbass. Luba, my grandmother and grandfather returned to their house, which wasn't damaged during the bombings. I will tell you something about my grandmother. She knew the Bible very well: both the Old and New testaments. After the war Luba's neighbor was a Christian priest named Father Vassiliy. In the evening he and my grandmother used to sit in the yard discussing religious subjects. The priest said that my grandmother was the best and most intelligent company he had ever had. At 86, I remember, my grandmother read newspapers, was interested in policy and any political events. My grandfather didn't care about these. My grandmother died in Gorlovka in 1967. My grandfather died before her in the 1950s. They remained religious people throughout their life and tried to observe traditions and celebrate holidays. They didn't go to synagogue often. They were both buried at the Jewish corner of the cemetery in Gorlovka.

Mama and I came to Enakievo. Or house was destroyed. It just collapsed from old age. The roof fell down and the windows were broken. But we moved in there anyway. In Enakievo I finished the fourth grade at school. I became a Pioneer there in the most routinely way - we just got our red neckties.

Uncle Foya demobilized at the end of 1947. He didn't come back to Donbass. When in 1940 the Soviet Army occupied Bukovina, Uncle Foya was among the first soldiers there on his tank. He was in Chernovtsy and the people welcomed the soldiers with flowers. He liked the town very much. He decided to move there and got married after he settled down in Chernovtsy (editor's note: Czernovitz in German: the town was the last frontier stop in the pre-1918 Austro-Hungarian Empire and retained a certain European culture.

In 1948 uncle Foya came to Enakievo and took me and Mama to Chernovtsy. Uncle Foya was married and their family had a room in a communal apartment. We stayed with them for some time. I went to the 5th grade of Russian school No. 2. The school was far from where we lived, but it was the best school in town. My mother worked making braziers at home for Fedkovich factory. She didn't get much for her work, but still, it was something. This money was basic in our family budget plus a small pension for my deceased father.

I was growing fast and was so weak that I couldn't make it up the stairs to our second floor classroom. Mama gave me cod-liver oil to improve my health. We had one textbook for several schoolchildren and we were doing our homework in groups. I was doing well at school. I don't remember how many Jewish children there were in our class. I was raised at a time when nationality didn't matter. Only in Chernovtsy did I begin to identify with Jewish nationality. Now, when looking at my school photographs, I realize there must have been quite a few Jews in that school. I wasn't a very sociable girl. The majority of my school friends happened to be Jewish. There are not many left in Chernovtsy. My friend Sima Grinfeld, Goldman after she married her husband, is in Israel. Frosia Koetskaya, another friend, died recently. Alla Kozinskaya is in America.

We were modest girls. We went to the parties wearing our school uniforms. Sometimes we went to the parties at the boys' school. Usually such parties were arranged on the Soviet holidays of the 1st of May or November 7, Constitution Day. In the morning we went to the parade and then had concerts and parties at school. We didn't celebrate holidays at home. Mama and I were poor. On holidays Mama tried to make a cake to make it more festive for me. We had holiday parties only on my birthday or at the New Year.

We had a good class and a good teacher. My favorite teacher taught the Russian language and literature. Her name was Bertha Iosifovna Ginsburg, a Jew, and she is still living, and I meet with her. She taught us to write and speak intelligently and thanks to her many of us entered the institutes. I was very fond of physics and mathematics. I became a Komsomol member when I was in the eighth grade. It didn't't change much in my life. I didn't care about ideology, but I realized that it would be easier to enter the institute for a Komsomol member. I've never been fond of social activities. I didn't have any hobbies besides studying.

In 1948 the campaign against cosmopolitism began. I remember somebody from our class brought in a poem by Ilia Erenburg. (Editor's Note: Ilia Erenburg (1891-1967) was a well-known and controversial Russian writer, and Jew. His adventure novels show the philosophic and satirical panorama of life in Europe and Russia in the 1910s and 20s. As a reporter, he was prolific and a strong Stalinist for years. His most lasting achievement is The Black Book, which he wrote with Vassily Grossman, another Jewish writer. The Black Book, written in 1946, was translated into English only 2002 and details with great specificity the massacre of Jews in the Soviet Union by both SS and Wehrmacht troops.)

I believe the title of the poem was "Why they don't like us" and it was about the attitude towards Jews, written in Russian. I copied it and showed my friend and Mama. Mama got very pale from fear and told me to throw it away while we were free. She told me to show it to no one. I was 12 years old and didn't understand much of it. None of our teachers or my schoolmates' parents suffered then. Unfortunately, I don't remember anything about the "Doctors' case."

I remember Stalin's death in March 1953. We all were crying at school - the girls and teachers. We all believed that the world had turned upside down. I don't remember crying. I didn't't cry often. I don't know whether people cried sincerely or just pretended, but there were lots of tears shed.

Uncle Foya and his family moved to Lvov (editor's note: Lemberg in German, another Austro-Hungarian city that first went to Poland, then the Soviet Union in 1945). He worked as a cab driver there. Mama and I lived in the same room where we had lived with them before. Mama was a beautiful woman and many men liked her a lot. But she was faithful to the memory of my father and had no thoughts about marrying again.

In 1954 I finished school. I wanted to be involved in polygraphy but there was no such department in Chernovtsy. I entered the Technology Department at the Lvov Institute of Polygraphy. I've never faced any anti-Semitism. Chernovtsy was a different town in this respect - the majority of its population was Jewish. There wasn't any anti-Semitism in Lvov or Novorossiysk where I had my job assignment upon graduation from the institute.

I lived in Lvov for five years. I had three friends who were my co-students, and we rented apartments and lived together. One of the girls was Ukrainian, from Ivano-Frankovsk--her name was Zina Odynets-- another one was a half-Jew from Lvov named Dina Shtykova, and the third was Bella Birman, a Jew from Kiev. We were very close friends. I don't remember any Jewish lecturer, but there might have been a few. When I was a fourth year student I began to look for an apartment and met Faina Vishnepolskaya. She was a doctor. Her husband had died and she didn't want to be alone in the apartment. Faina had a three-room apartment. She was a tall Jew and was very possessive and decisive. She didn't seem to welcome me at the beginning. She gave me keys to her apartment and I moved in. My room was cold in winter and I moved into the room where she was residing. We lived like a family. We cooked together and shared everything. We became great friends and stayed such until she died. Later I came to Lvov on business trips and came to Faina like to my home. After Faina died, I remained a friend of her niece Sofia until she emigrated to Israel in the 1970s.

Life in Lvov was beautiful. My friends and I went to concerts and theaters. There was a beautiful Opera house in Lvov and we didn't miss a single performance. We liked to go to the Philharmonic. We bought the cheapest tickets; they were called "student tickets." Lvov is a beautiful ancient town with beautiful architecture. We enjoyed walking in the town, looking at its buildings.

In 1959 after graduation I got a job assignment at the printing house in Novorossiysk. I worked there for two years. I was foreman and then shop supervisor. I also rented an apartment there. In two years I returned home to Mama. I found a job at the production association that was converted into the chemical goods in two years' time. I was a forewoman at first and then had engineering positions. We had a very nice and intelligent director who advocated for internationalist ideas. Perhaps, credit must be given to him that we didn't have any expressions of anti-Semitism at our factory. I worked there my whole life until retirement. I lived with my mother. We received a two-room apartment as a family of the deceased at the front. Now I live here alone.

I remember how many Jews were emigrating to Israel in the 1970s. There were no condemning meetings at our enterprise. Once an engineer who was going to emigrate was transferred to the worker's position two months before his departure. I sympathized with those who were going to leave. I had nobody there to go to. Later, after Uncle Foya died his son and his wife moved to Israel in the 1990s. Mama and I didn't even raise the issue of emigration. I'm used to this life and it would be difficult to get used to a different way of life. Besides, I have a heart problem and high blood pressure, and I cannot stand the heat. My close friend moved there. We correspond with her. She is retired and has a good life there. Israel is a beautiful country taking good care of its people. But I have no energy to start life anew.

I was gradually promoted at work and my salary was increasing. I received bonuses. Mama was pensioned by then. She had a very small pension. We could provide for ourselves, though. Mama died in 1992. Since then I've lived alone. (Editor's Note: The interviewee didn't want to go into the details of her personal life. She probably didn't have a family, because she never had an opportunity to arrange her personal life).

The Jewish way of life has been actively promoted in the recent years. Hesed undertakes lots of activities. There are different clubs and many activities in Hesed. I like the literature club and the aging people's club. We come there to communicate, meet and see one another. There are different people in those clubs. We discuss interesting subjects and read in front of the audience. It is important that there is a place where people can talk. We celebrate holidays together. We celebrated Purim in the theater, for example. They also have a program for children - "Mazltov". I like Director, Mr. Fooks. He is full of energy and sociable and sincere man. He likes his work and enjoys caring about people and we like him, too. Recently, I have come to identify myself as a Jew. I am concerned about Israel. I wouldn't treat a person in a different way because his nationality is different. Most important for me is whether a person is honest. Recently, I have communicated mostly with Jews. I feel close to them. I am a radio announcer. We have a radio program in Yiddish and Ukrainian that is broadcast once a month - "The Jewish Word". It lasts for half an hour but preparation takes a long while. It is an interesting process and I like the feeling that I'm doing something that people need. We get many letters from our listeners after every broadcast. I know that our work is not in vain.

I began to study the history of the Jewish people. Unfortunately, it is much worse with the religion. I have no basis to accept it. I'm not prepared. It is all new to me and I'm missing something. But I hope that I still have time.