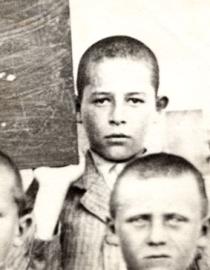

Zoltan Blum

Gherla

Romania

Interviewer: Cosmina Paul

Date of the interview: July 2005

Mr. Zoltan Blum is the only Jewish survivor of the Holocaust in Gherla. He takes care of the synagogue that was left in this town. On Jewish holidays, he travels to one of the larger Jewish communities in the region – Dej or Cluj-Napoca.

He lives with his wife in a medium-sized house located on a street that’s close to the Armenian church – the town’s most important historical monument.

The house still lacks finishing; the rooms and the garden are decorated in a simple fashion. Every summer, the Blums spend their time on the porch, reminiscing...

- My family background

I have no recollection of my paternal grandfather; all I know is that he was a Blum. He spoke Jewish [Yiddish]. In fact, let me tell you something: every Jew from this region, from Transylvania, could speak Yiddish. But they used the language that served them best.

They spoke Hungarian when talking to Hungarians and Romanian when talking to Romanians, as their trades required them to. What I mean is that the Jews had nothing but respect for foreigners; we have this saying: ‘Be a good Jew, but also respect the country you live in.’ For the Jews in Gherla, this country was Romania. The fact that they all sent their children to the Romanian school gives you an idea of the extent to which they respected their country.

As for the language, it’s like I said: we used Yiddish at home and, for the rest, we used the language of our interlocutors. I heard my paternal grandfather was a religious man, but not a bigot. He didn’t wear a beard – I could say he was ‘modern’, using a term of nowadays.

He was buried in a nearby commune, Unguras, at the Jewish cemetery [Editor’s note: There are 25 km from Gherla to Unguras.] My father took me to his grave. He brought by horse carriage a gravestone which he placed on his tomb. At that time, I was about 7-8. This means that it happened in 1934-1935. That’s all I can remember.

The name of my paternal grandmother was Scheindl Blum. Blum was the name he took from my grandfather and Scheindl means ‘beautiful’ or, better yet, ‘pretty’. She spoke Jewish. But she also spoke Romanian and Hungarian. She only ate kosher food. She was religious and she wore a wig. I did meet her, but I was only a small kid – I was 4-5 years old. All I can remember is how I used to help her get to the garden, for she had become rather shortsighted. She died in 1932 or 1933 and she was buried at our Jewish cemetery [in Gherla]. Although we lived in Fizes [Editor’s note: Fizesul Gherlei, 6 km away from Gherla], we brought her over here because Tiberiu Blum lived here [one of Scheindl Blum’s sons and brother of Mr. Blum’s father].

My father had three brothers. One of them lived in Gherla. His name was Tiberiu Blum, but I couldn’t tell you where he was born. I can’t even remember his Jewish name. He owned a fabrics store here in Gherla. His wife was Jewish. He had five children: Beri – Ber would be the correct form in Yiddish and this is how he was actually registered; Zalman – Leibe in Yiddish; Mendl – which means Eugen. There were also two daughters, but I can’t remember their names. Beri, Mendi, and Leibi are still alive today.

My father’s second brother was Iosif Blum. His Jewish name was Iosef. He lived in the commune of Sannicoara, in Cluj County – about 30 km away from Gherla. [Editor’s note: The exact distance is 36 km.] It was a small commune located in a valley. He spoke Romanian very often because he lived in a Romanian community. He was a tradesman. He owned a store of ‘colonial goods’ [Editor’s note: pepper, tea, cocoa etc.] as they used to call them back then. He was married and he had three children.

One was named Lajos – he was officially registered under the Romanian name of Ludovic [Ludvik in Yiddish]. The other one lived in Arad. I’m sure he was a boy too, but I can’t remember his name. Iosif also had a daughter whose name is Vilma. The children were all born long before the Holocaust. Of the three children, only Ludovic and Vilma got deported. They both survived. Before being deported, Iosif was sent to work [forced labor].

My father’s third brother was Martin Blum. He was very religious and he only spoke Yiddish to us. Martin is the Romanian translation of Mordechai. He was never married and he didn’t have children. He lived in Fizesul Gherlei and was a tradesman. All these brothers used Yiddish at home and Romanian and Hungarian outside their home. They were all deported and none of them came back. They were assembled with the others here [in Gherla], at the brick factory. I remember I was with them in the brick factory in Gherla, then in the brick factory in Cluj. The final destination was Auschwitz. There we lost track of one another.

My father’s name was Mauritiu Blum – Moshe Iankef by his Jewish name. In the spoken language, it was Moishe. He was born in 1888. I can’t remember the month. As for the year, I only learnt it later and with great difficulty, going through papers. [Editor’s note: Mr. Blum refers to the documents regarding the origin of his parents that he needed after World War II.] I was only a child and my parents didn’t talk about such things with us… They were busy with their own things.

It was only after I had come back from deportation that I needed to know these things – and I found them in papers. We didn’t celebrate birthdays back then – people had other things on their minds. A child’s birthday may not have passed unnoticed, but, generally speaking, people were much more concerned with providing for their families than with anniversaries. This is how things went. My father was probably born in Unguras, since my grandfather was buried there – but I can’t pledge for that.

My father didn’t wear a beard, but he didn’t shave either – Jews aren’t allowed to. He simply trimmed his beard off using a special device and some powder. Not wearing a beard, one could say he was pretty modern. He didn’t wear a kippah, but he always wore a hat. He went to the cheder, like any other Jewish boy.

They taught prayers there. No matter how poor a family was, their children still went to the cheder. It was vital, since they learnt the morning and the evening prayers and the basics of religion. Apart from the cheder, my father went to the public school.

My father served in the army of Austria-Hungary during World War I, but I don’t know where. For a while, he lived somewhere near Budesti [Editor’s note: in Bistrita-Nasaud County, 57 km away from Gherla]. He worked as a sort of manager, but I couldn’t tell you for whom; all I know is that it wasn’t in some factory, but on a farm. Then he moved to Fizesul Gherlei [Editor’s note: 6 km away from Gherla].

I don’t know how my parents met each other or the circumstances of their marriage. All I know is that, after the war, I had to go to the commune of Budesti to get the papers I needed – which proves they met and got married there. But they never told me anything about it.

I think my maternal grandfather’s name was Gaspar Salamon. I have no recollection of my maternal grandparents because they lived in a different place than ours – the commune of Budesti, in Bistrita-Nasaud County. I think they were farmers – I remember my mother saying she had some land over there. As for my maternal grandmother, I never met her.

My mother’s name was Berta Blum – Berta Salamon by her maiden’s name. She was born in 1888, in the commune of Budesti. My mother always wore a wig – at least, this is how I remember her from the moment my mind started to store memories. She also went to bed wearing a kerchief.

She was very religious. She had poultry slaughtered by the shochet alone, and, if he was missing, we would travel to Gherla. We only ate kosher. She was a great cook. The local women didn’t know how to make too many cakes, so they used to come to my mother for help.

We had a large stove – since we had a large family – and all those women baked their cakes at our place. They would bring the eggs, the flour, and the oil, and my mother would take care of the rest, using our own pots. She also cooked cakes for weddings. I remember the pancove and the minciunele [Editor’s note: local cakes that are more or less similar to doughnuts].

My mother used to force feed geese. He bought them from a peasant, laid them on the ground and force fed them. Have you ever seen how this is done? With one hand she opened the goose’s beak and with the other she stuffed corn beans down its throat. Now they do it with a mechanical device.

Then she had it slaughtered, but the liver was kept, not eaten all at once. Geese sometimes choked – since beans went down the trachea, the same way air did. My mother knew what to do: she would put her hand down the bird’s throat, locate the bean, and pull it out. Peasants would come to my mother’s: ‘We’re going to Mrs. Blum ‘cause our goose choked.’

Jews aren’t allowed to slaughter chicken themselves – that’s the shochet’s job. When she got back, my mother would remove the feathers by hand and fry it a little, to make sure the body is clean. She used to keep the feathers. In winter my mother would summon a claca [Editor’s note: Romanian term designating a group of peasants that gather to do voluntary work in order to help one another].

Every woman in our village was there – it didn’t matter if she was Romanian of Hungarian; there were even Gypsy women. Back in those days, Gypsies had trades of their own – they made stoves or sickles, for instance.

My mother offered them sweet brandy and they all sat and turned feathers into down to make pillows for their daughters’ dowry. The pillows could only contain down, not feather stubs. The down was stored in sacks. My mother used to keep the sacks on the bed and she removed them when we went to sleep.

The pillow cases were kept in the wardrobe. Those cases were only filled when a young daughter got married. By the time we got deported, my mother had collected two sacks of down weighing about 30 kilograms each. They went down the drain, like everything else we left behind…

Here are my siblings in chronological order. The eldest was Matei Blum – Mayer in Yiddish. He was born in 1917. Then came Ernest Blum – Gershun in Yiddish, like that musician, [George] Gershwin. He was born in 1919. My only sister, Margareta Blum – also known as Malvina – was born in 1921. Eugen Blum was born in 1925. I was the youngest.

Growing up

My name is Zoltan Blum. This is the name I grew up with. But my parents also gave me a Hebrew name, Sloimer Zalman [Mr. Blum refers to the brit milah ceremony]. Zalman is a rough translation of Zoltan, you see. Many Hungarians use the diminutive form for Zoltan, which is Zoli. But I am recorded as Zoltan in all the official papers. I was born on 10 October 1927 in the commune of Fizesul Gherlei.

At the time when I was a kid, my parents didn’t talk to us much… Their problems kept them busy. They did own a sort of store, but it didn’t generate enough income to support the entire family. We didn’t own land. There used to be a law that prohibited Jews from owning real estate – I only learnt about this after World War II –, but, eventually, they acquired the right to be citizens [Editor’s note: The Romanian Constitution of 1923 granted citizenship to the Jews.] 1.

To be honest, I didn’t read about this in a book, I only heard about it… Many pointed out that Jews had a lot of money because they were involved in trade, but no one said why they were tradesmen. Well, the reason is that they didn’t have the right to own land, so they couldn’t support themselves otherwise. You see? These are the facts.

So my parents had a store and a bar – and that was all. When he was deported to Auschwitz, my father’s list of debtors was that thick… He used to sell on credit and the amount of debt that had accumulated was so high, that it was almost worth the entire store! The store was located in our house. We had four rooms.

Two were the living quarters, one was for the store, and one was for the bar. In addition, we had a small summer kitchen. We also had a courtyard and a vegetable garden. My mother was in charge with the garden. She would grow tomatoes, cucumbers and the likes. My parents were poor. They didn’t have a horse cart, so they walked.

My parents were only too good. As good as gold. They were very devout [when it came to food]. Every time I went out to play with the peasants’ children, I was warned: ‘You may go, but don’t eat anything but fruit.’ And I obeyed. We only ate kosher meals at home. We had separate pots for dairy products and for meat.

We also had a larger vessel that we called parva – meaning large cup or bucket –, where water was stored. Using the water from the parva for cooking both dairies and meat was okay; but our faith didn’t allow us to take the water from the dairy products and use it to cook meat.

We didn’t eat pork – Jews are not allowed to eat any animal whose hooves are not split or that doesn’t ruminate. Take camels, for instance: they are ruminants, but their hooves are not split. Furthermore, we can’t eat blood. We didn’t just roast the chicken right after having it slaughtered. We took it home and sank it in cold water, then in salty water, then in cold water again – to remove all trace of blood.

As you know, Jews must have the blood veins removed from the meat. But the shochetim from the parts where I lived didn’t know how to do this, so we never ate the rear part of the animals – only the front part. Some people made a joke out of this: ‘Do you know why Jews don’t eat the rear part of the animal?

Because the animal went out from the barn and scratched its behind against a Christian cross’. The truth is the shochetim weren’t skillful enough to remove the veins. In Israel, for instance, they also eat the rear part – but they have trained people who know how to remove the veins.

My parents were not extremely religious. Being extremely religious means that you wear beard and whiskers, wear a kind of tallit [tallit katan]… We did wear a kippah though. We, the children, wanted to wear straw hats, just like the other [Christian] kids and my dear mother bought us ones and let us wear them, but sewed a kippah on the inside.

This way, she wanted to make sure that our heads were covered at all times. When we went caroling with the other boys [on Christmas’ Eve], my good mother always told us: ‘You may go, but be careful what you eat! Don’t accept bagels or anything else except apples. And walnuts.

And so we did. When the Christian Easter came, it was the same story – we didn’t eat anything from the peasants. I still wonder how I managed to refrain myself from ever eating bacon as a boy, despite the fact that I was surrounded by Christian friends who would have kept the ‘secret’. Can you imagine that? My mother’s word was that strong! She told us ‘you can’t do that’ and we listened to her. I never ate bacon before we returned [from deportation]. I committed to tradition from all my heart. The kashrut was sacred.

When there was a holiday, we would have a chicken slaughtered. Purim wasn’t such a big fuss, like it’s today. We went to the prayer house and my mother baked a large bagel. She bought milk from the village and made some butter for us. She lived by the principle that the children mustn’t lack anything – especially food.

Maybe our clothes weren’t always new and shiny, but food was never a problem. Even the religion says that it is a sin not to have anything to eat on holidays, because you cannot focus on a prayer properly when your mind keeps saying ‘What will I eat’? There was no synagogue in Fizesul Gherlei – only a prayer house.

Any house can be a prayer house as long as it has been stripped of beds and storing furniture. It can only have tables and chairs. That house wasn’t Jewish-owned – we just rented it from the Christians; no one lived there. The place is deserted now.

The tradition requests that a deserted house be demolished – and this goes for a synagogue too. Anyway, it’s better to demolish it than to let it be used by another cult. [Editor’s note: Mr. Blum likes to refer to sayings from the Romanian and Jewish folklore whose authenticity cannot be verified.]

When I was little we used to visit my uncle and aunt. I remember we came with our parents here, in Gherla, especially before the high holidays. They took us to the Jewish bathhouse [mikveh] before Rosh Hashanah and before Yom Kippur. We didn’t have a Jewish bathhouse in our village and the closest one was in Gherla.

Sometimes they took us to the tailor’s and ordered new clothes for us. In that period we went to my uncle’s with my mother and father, but we went only with them, children were not allowed to walk back and forth by themselves, but only with their parents. On Saturday, we only washed at home.

On every holiday, we would all have a large meal. No matter how poor a Jew was, he had to have a decent meal on holidays. My mother laid a white tablecloth (which wasn’t for everyday use) and two candles. As the candles were lit, we would say the ‘Baruch ata...’ prayer.

In my childhood I did have my share of being called a Jew – but let’s not forget that my classmates were country boys. In the first six years of school, I studied in Romanian. Then, in 7th grade, we switched to Hungarian [from 1940, during the ‘Hungarian era’] 2. I also went to the Jewish school, the cheder, where they taught us the Jewish faith. I woke up at 6 in the morning. My mother put something to eat in my bag and sent me to the cheder. There we learnt the prayers, as well as writing and reading in Hebrew.

But we only got as far as learning to read… I must have been three years old or so when I started going to the cheder. From there, I would head straight to the kindergarten or, when I got older, to school. At noon, I came back home, where I had lunch, then played with the others a little. In the afternoon, it was back to the cheder. We studied the Talmud Torah and the rest.

We learnt the prayers we were supposed to say on various occasions: in the morning, in the evening, before biting from the bread, before washing [our hands]… We learnt ‘Sema Israel’ – the Hebrew equivalent of ‘Our Father’. We also learnt how to read. The elders did a big mistake.

We say our prayers in Hebrew, but talk in Yiddish. There’s a big difference between the two. So I recited ‘Sema Israel’ in Hebrew or learnt the weekly pericope in Hebrew, but I used Yiddish to express myself. [Editor’s note: Students read in old Hebrew, but commented on the texts in Yiddish.] And the teacher translated for us. It was very, very hard. But we didn’t realize this contradiction. At home it was the same: we used Yiddish to communicate, but the prayers were in Hebrew. At least until the deportation.

I can hardly remember my bar mitzvah. All I recall is that, before the event proper, we learnt how to put on the tefillin and the tallit, and we memorized the prayer. It took place in our village – there were ten men, so it could be done.

In 1938 and 1939 the Goga-Cuza cabinet 3 was in power. At the Romanian public school there was only one teacher who picked on my brother Eugen for being Jewish. His name was Calugaru and he was a local. As we were devout, my brother refused to light the fire on Saturday, so this teacher forced his head inside the stove. I was a very bad pupil, as opposed to my siblings, who were always the first in their class. They say Jews have had to deal with rejection since time immemorial. And it’s true.

If it rains on Easter, they say it’s because the Jews have their own holiday. You see? Jews were always responsible for everything. This is why Jews have always kept a low profile: they didn’t get involved in politics and in debates, and they respected other people’s faith.

They had to respect the others, because those others were the ones who bought from them. Right? Then the Hungarians came in 1940 4. To tell you the truth, I didn’t realize what was going on. We were hoping to get rid of something bad [the persecutions endured under the Romanian rule], but things only went from bad to worse. You can imagine my confusion.

- During the war

People were envious of the Jews, because they were the first in almost any field. They say Jews are smarter. Well, I don’t think that Jews are smarter; I think they were forced to be smarter in order not to starve. They were forced to study hard and acquire an education in order to advance. About a tenth of the Jews were lawyers, doctors or teachers.

The rest were workers, craftsmen – shoemakers, belt makers, tailors etc. – or tradesmen. There was this commune called Sanmartin [Editor’s note: Mr. Blum probably refers to a village located 7 kilometers away from Oradea, in Bihor County. There is another village with the same name located 16 kilometers away from Miercurea Ciuc, in Harghita County.], where there lived Jewish farmers.

But they only sold goods to other Jews. That’s because the [non-Jewish] farmers prepare the cheese in the same pots they used for bacon. So there had to be Jewish peasants who made kosher cheese and sold it to other Jews. Those devout and pure-hearted Jewish peasants were mostly shepherds from Maramures.

Then there were the Jews who went from village to village carrying wicker baskets with “albastreala” [Editor’s note: Romanian for an indigo-blue substance that can decompose the color yellow and that is used at home and in industry to increase the whiteness of some objects.]. When women did laundry, they added albasteala to make them look cleaner and smell better. It also went by the name of mireala. It was also used to give lime a bluish tint. [Editor’s note: These practices can still be found today in the backwoods of Romania.]

But I can tell you that there were people who lived from one day to the next. They formed the destitute peasantry. I know this from my own experience. There were people who came to my father’s store to trade an egg for four lumps of sugar.

They went to the butcher’s and asked for a funt of meat – that only meant a quarter of a kilogram. [Editor’s note: ‘Funt’ is a Regional form of the Romanian ‘pfund’, an old weight measure unit equal to 0.5 or 0.25 kg – depending on the region where it was used. It comes from the German ‘Pfund’.]

People just couldn’t afford to buy by the kilogram. One would say ‘Sell me on credit and I’ll pay you on Saturday evening, as I’m going to Gherla to chop wood.’ He went to Gherla, did the work, got paid, and came back on foot, wearing opinci [Editor’s note: ‘Opinca’, pl. ‘opinci’ (Romanian), The oldest type of footwear is peasant sandals (opinci) worn with woollen or felt foot wraps (obiele) or woollen socks (caltuni). http://www.eliznik.org.uk/RomaniaPortul/footwear.htm]. ‘How much do I owe you, Mr. Blum?’ he would ask. There were eight Jewish families in Fizesul Gherlei: Mauritiu Blum, Herman Hiller, Weiss, Sigismund Feierstein, Rozika Deutsch, Baumel, Szerena Abraham, and Ludovic Feierstein.

We looked different from the peasants because of how we dressed. The peasants wore homemade clothes – like some still do today. As of 1943 or so, my own mother started to weave clothes at home, as we didn’t have money to buy new ones. We began to have our boots patched too.

We would show my father a broken boot, and he’d say: ‘Well, go and have another patch added.’ When the Passover had passed, people gave up their warm clothes and only wore a long shirt. That was all – no underwear or anything. We all had a long shirt and walked around barefoot. We only wore shoes on holidays. We, the children, would join the peasants’ kids and play in the field barefoot. My parents dressed modestly too – but they were Jewish clothes.

All my brothers graduated from primary school in Fizesul Gherlei 7 grades. Matei went to Gherla to study in a commerce school for an extra five years I believe. He worked for a Jew who owned a hardware store. But, one day, the man told him: ‘My boy, you should go home; I have no use for you here anymore’ – they had confiscated his store. So my brother came back home.

My parents owned a store until 1943. Then things got really hard… Here’s what happened. The store sold most of the items needed in the countryside: tobacco, alcohol, petrol, cotton, sugar, and so on and so forth. But the State began to enforce its monopoly in trading most of these goods; they started with tobacco and alcohol, but didn’t stop there. Soon, the items that my father could sell legally were limited to so few (candy, flour etc.), that the store couldn’t secure our living anymore. My parents had a very hard time.

Today I have this little home and a small pension – but it’s already more than we had back then… If they bought food, they ran out of money and couldn’t renew the store’s supplies anymore… Plus they had to provide clothes for the two sons who went to work [in the forced labor detachments] – and the Army didn’t give them anything. And there were three more children at home to take care of. Things were very, very tough. You can’t imagine how tough they were unless you were there… This is what happened in 1943.

After 1943 we had to wear the Yellow Star 5. Of course we had to. When we were among kids of our age – Romanians and Hungarians – we felt ashamed. It’s not like they pointed their fingers at us or beat us. It’s just that we were sort of embarrassed. But the only times we really felt discrimination was when we went to the so-called ‘pre-military training’ – they called it Levente 6 in Hungarian. We weren’t allowed to walk alongside non-Jewish recruits. They had special caps, while we only wore our everyday clothes and caps.

They took us to work at the priest’s house or at the places of the other Levente commanders. Most of them gave us something to eat. But the priest’s wife didn’t let us sit at their table. Nor did the notary, who had us clean his garden. If truth be told, we weren’t treated very badly – it’s just that we were tagged. Matei and Ernest were drafted and sent to the Hungarian labor detachments in 1942 and, respectively, in 1943. They didn’t give them working clothes – they had to bring their own.

After my older brothers, Matei and Ernest, had been taken to forced labor – along with all the other Jewish men –, my brother and I started working with horse-pulled carts. We borrowed them from the Jews who had been left at home (women, children and elderly ones). What did we use them for? Well, the Hungarians were looking for natural gas.

The Romanians were already extracting it in Sarmas and Sarmasel [Editor’s note: Currently in Mures County, in an area that remained under Romanian authority even after the Second Vienna Dictate] 4 and we were close to the border, which passed through Sucutard [currently in Cluj County] and next to the lake. So the Hungarians thought there must be natural gas here too.

They were using a method of detection based on coal. The coal was brought to Gherla by train from the mines and it had to be carried further by cart. This is where my brother and I stepped in. But we didn’t do it for nothing, you know? Both the families who owned the carts and us got paid.

We began to sense something bad was going to happen [before the deportation], but my mother kept saying: ‘Oh, it’s nothing really; they’ll take us to work, but the war will be over soon and we’ll be right back.’ At 16, I was the youngest in my family. Who could have foreseen the deportations? When talking to each other – in Yiddish –, my mother and father seemed to agree that we would only be taken to work somewhere else and we would return as soon as the war was over. My poor mother! She genuinely believed in this…

Then, one morning, in 1944, my brother and I were on our way to two Jewish families who lent us their carts. They lived in the opposite part of the village. When we reached the center of the village and crossed the bridge – I remember it was a clear morning, in the month of May – someone called us to the mayor’s office. We entered and found two Hungarian gendarmes and the mayor. ‘You are under arrest!’ he announced. I had no idea what ‘arrest’ meant, since I had never been ‘under arrest’.

But my brother Eugen, who was 2 years older than me, knew what it meant. They didn’t let us return home. They escorted us to the Jew who lived closest to the mayor’s office – a destitute fellow who made pottery and whose house was near the Christian-Orthodox church. He had a horse and a cart, so they made him and his family (4-5 children) board the cart and prepare to go. Then they took us home to get dressed for the road.

Our poor mother and father were already aware of what was going on. When we got home, the house was already surrounded by pre-military servicemen. When I got inside, my mother told me: ‘Put on an extra change of clothes.’ I packed a change of clothes and I put on an extra change, like she said.

My father grabbed some bread, a pillow and things like that – they didn’t let us exceed a certain weight. The carts were already waiting for us outside. We didn’t have a cart, so a Hungarian neighbor carried us in his. Most of the other Jews did have their own cart.

So they put us in the cart and took us to the brick factory in Gherla. All the carts were sent back to the village, where the deserted houses lay defenseless, with everything that had been left behind: clothes, furniture, and other belongings. As soon as we got to the factory, they confiscated my father’s wedding ring, my mother’s earrings, and my sister’s earrings too. The place was surrounded by gendarmes. We stayed there two or three weeks – I can’t remember exactly, but I think there were two.

We lived the sheds that were used to manufacture bricks. They didn’t have walls – just ceilings. We could only rely on the things we had brought along. Think about it: there we were, all the Jews from the villages located in Gherla’s proximity – a total of about 7,000 people. Each village had at least two or three Jewish families.

One day, the order to move out came. We could no longer carry any of the few things we had brought along – not even a pillow… They put us in train cars whose windows had been covered with planks and took us straight to the brick factory in Cluj. I was only a child and, although I was witnessing those things first hand, I didn’t realize why they were doing them. I’ll tell you the truth: after two weeks spent in Cluj, any sense of normality had been lost. Everyone cried. The only people who still prayed were rabbis and the really devout…

The others had lost all hope in God and even claimed – may God forgive me – that there is no God! You can imagine how serious things were, if people had reached this state of mind… And things were pretty serious. There were Jews whose legs were burnt with red-hot iron to make them confess where they had hidden their gold. They didn’t torture the ones from the countryside – only those who had owned large stores and were known to be well-off. You know how life is: some people get rich, others don’t.

My parents, for instance, didn’t go through this ordeal, because they were known to be poor – our captors were pretty well informed. No one came to help us and bring us food because the gendarmes were everywhere. Anyone who claims otherwise is making up stories! [Editor’s note: Mr. Blum probably refers to the individuals who claim to have helped the Jews in distress back in those days.] You know how it is: … There may have been one or two people, but the vast majority didn’t raise a finger. You know why? They were afraid.

Or they simply didn’t care: ‘Why go there and help them? Let them rot in hell!’ There are two kinds of human beings in the world: good and bad. When we were deported, some thought ‘It’s a good thing they’re finally gone’ and others thought ‘Maybe, but what about the children?’ You see? No one did anything. Romanians, Hungarians, Gypsies, Germans and the rest – they all just sat there and watched.

The way from Cluj to Auschwitz was by train. We were put in cattle cars. [Editor’s note: 16,148 Jews were deported from Cluj in the period 25 May - 9 June 1944.] Forgive me for saying this, but there was no place to relieve ourselves. No water or anything else.

Babies were crying in the arms of their mothers, whose bosoms were dry for lack of food. Whenever an elderly died, we would stack the body upon other corpses, to make more room in the crowded car. I didn’t do this myself, but I witnessed it being done. I was still young, so I didn’t quite grasp the meaning of what was going on. But can you imagine what was going on in that car? We finally got to Auschwitz [Mr. Blum’s voice is more and more feeble], and they made us get off.

The whole family was there. The Nazis were selecting the newly arrived and two groups were being formed: men and women. My brother Eugen and I were pointed in one direction, while my mother and my sister were sent to the other group. I don’t know what became of them. That was the last time I ever saw them… Some inmates later told me that they spotted them at work – which means they weren’t sent straight to the gas chambers. This is how we ended up in the Auschwitz-Birkenau labor camp.

They shaved our heads, removed our clothes, made us take a bath, and had us tattooed with numbers. I ceased to be an individual with a name as I became ‘Auschwitz 10919’ [Interviewer’s note: Mr. Blum shows the tattoo on his left forearm.]. There was a factory near Auschwitz. It belonged to I.G. Farben [German industrial conglomerate] and was called Buna. [Editor’s note: synthetic rubber plant located at the outskirts of the Polish town of Monowice; it was established in the spring of 1941.] 22,000 of us ‘Heftling’ – which means ‘inmates’ – worked there. [Editor’s note: Established in 1942, Buna was the largest sub-camp of Auschwitz.

In November 1943, it became a separate administrative unit designated Auschwitz III. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/Buna.html]. Next to our camp there was a place where they kept American prisoners of war – captured in combat or parachuted from planes and caught on enemy territory. They let them keep their uniform. There were thousands of them, but we only saw them from a distance. There was no contact with them – it was strictly forbidden.

In the morning we would get a sort of coffee. That’s what they called it, but it was anything but coffee – it was a substitute. They also gave us a little piece of bread. I don’t know what they made it from, but it wasn’t nourishing at all. You know that ‘real’ bread is rolled in flour after it’s done, to prevent loaves from sticking to one another – well, they rolled it in sawdust over there. A loaf was split in four quarters and had to suffice four people. There was also the synthetic marmalade.

And let’s not forget the ‘sausage’ – they called it ‘Wurst’; it looked like foam and was made from leftovers – certainly not meat or anything like it. At noon they gave us beet – the kind of beet used to feed cattle, not sugar beet. In the evening we got a sort of soup – but never as much as we wanted. The number of ladlefuls to which every inmate was entitled was very limited.

As for the ‘plates’, they were coarse metal bowls that were never enough. You had to wait for someone to finish eating to get their bowl. There were 50-100 bowls for ‘Essen’ – which means ‘food’ – and many more inmates. Trust me, we were like animals! It was every man for himself. If you didn’t hold on to your piece of bread, another inmate would grab it from you. Like animals, really.

In the morning and in the evening they aligned us and counted us. None of the 22,000 inmates was allowed to miss that count, unless he or she was dead. The wake-up call was at 4 or 5 a.m. They started early because they had to move us out of the camp, to the factory. It was already 10 o’clock when everyone had left the camp.

The inmates aligned for counting according to their barracks. The head of each barracks – called block leader – stood at the front of each group. I can’t remember the number of the barracks I lived in.

I only remember that the block leader was a political prisoner, as his badge indicated – a red inverted triangle superimposed upon a yellow one, forming the Star of David. I had my own badge here, on the jacket, and here, on the pants. [Editor’s note: Nazi concentration camp badges, made primarily of inverted triangles, were used to identify the reason the prisoners had been placed there.

The triangles were made of fabric and were sewn on jackets and shirts. These had specific meanings indicated by their color and shape: some groups had to put letter insignia on their triangles to denote country of origin. Red triangle with a letter: ‘P’ (‘Polen’, Poles), ‘T’ (‘Tschechen’, Czechs).

The most common colors were: black for the mentally retarded, alcoholics, vagrants, the habitually ‘Work-Shy’, or a woman jailed for ‘anti-social behavior’; green was for criminals; pink was for a homosexual or bisexual man; purple was for the Jehovah's Witnesses; red was for a political prisoner. Double triangles: two superimposed yellow triangles forming the Star of David was for a Jew, including Jews by practice or descent; red inverted triangle superimposed upon a yellow one, forming the Star of David was to tag Jewish political prisoners.

There were many markings and combinations.] The counting was made by the ‘Schreibestube’ [clerks], who kept a record of us all. Then the SS officer came and redid the counting. Then the block leader called our names. After we had eaten in the barracks, we would align according to the work squad we belonged to. Each squad was led by a Kapo wearing a green triangle.

Those were the actual convicts. The Nazis picked them from regular prisons and sent them to concentration camps, to be in charge of the inmates. They came in various forms – some were good people, some weren’t... ‘Hundert und fünf und fünfzich’ – 155: that was my work squad. When the block leader gave the order, we all went out marching in the sound of band tunes. When we got to the gates of the camp, there was a final counting. Then we went to work, with the Kapo in front.

We worked at the construction site of the new factory. There wasn’t such thing as a work schedule: we practically worked till we dropped. There were certain rules for the ‘deployment’ of the work squads. The SS would have them move in a certain order. We had to wait until we could line up and start marching. The factory was located about one and a half kilometer away from the camp. We walked all the way. Some began working at the construction proper, others did other things. I [recently] got involved in a discussion about gas.

I watched on TV that blast which happened in Bucharest. And I recalled the pipes… I was working at some sort of concrete foundation they were digging in the dirt; it was narrow and several kilometers long. I imagine they were planning to insert pipes, like one would do in the case of a refinery. That’s what I think they were doing.

The site was located next to the existing factory and was followed by two kilometers of empty land. Several squads worked there. The premises were surrounded with barbed wire and watched by guards posted every 50-100 meters. There was also an electrified fence. Just like in the camp. Those who claimed it was possible to escape from the camp didn’t know what they were talking about.

There were electrified barbed wire fences everywhere – so it was impossible to escape. The few attempts were mostly made by people who had lost all hope; they would usually be shot by the guard from the tower before they even got to the first fence. No one was allowed to pass that fence.

There was a sign with a skull and the word ‘Achtung!’ [‘Keep out!’], indicating that the territory beyond that line was off-limits. Further away there was another barbed wire, then another fence, then a final fence. They were all electrified and their height increased gradually. As if they weren’t enough, there was also the guard tower, outside the camp.

The barracks were very crowded – I think there were at least three hundred of us in each block. There were three rows of ‘beds’ and we were as crammed up as sardines. During the night, if one wanted to turn around, he caused the entire row to turn around at the same time. No mattresses, just straw. And there was a blanket ‘downstairs’ and one ‘upstairs’. We didn’t have separate beds – just three rows of planks.

There were times when we were so many that they had to use Zertlger. That was a sort of tent – like the ones the military use today – that could accommodate some twenty people. The worst thing that could happen to a tent dweller was to end up in the upper part – the sun really heated up that tent.

The transports kept arriving and there was no room for new-comers anymore. To be honest, I can’t remember exactly why they took us out of the barracks and put us there [in the tent]. But I suppose they did it to make room for the new-comers. We were already ‘well trained’ – we had got used to the camp’s routine. The Blockführer [block leader] simply showed up one day and told us: ‘Everybody follow me! From now on, this is where you will sleep.’

My brother and I lived in the same block; we even slept next to each other. I had the ‘bed’ no. 19 and he had no. 20. I was inmate no. 10919 and he was inmate no. 10920. He was a handsome fellow. So I kept very much in touch with my brother, but I didn’t know anything about the other members of my family. And I never found out what happened to them.

One day I hurt my hand [the index finger of the right hand]. The camp had a sort of infirmary, but the sick and wounded that got there didn’t come back alive – unless they were easily recoverable. The camp needed laborers, not sick people! IG Farben paid the SS a certain amount for each inmate that worked for them.

The corporation had a sort of contract with the Third Reich. So the SS had no interest in killing us all at once when they could trade us as workforce. This is why they built this infirmary. I remember this doctor from Cluj – his name was Kiraly. He took me to the infirmary and inserted a rubber tube in my finger to drain the pus. He’s one of the few people in the camp that I remember.

The camp was a terrible nightmare. And I believe the entire mankind should feel ashamed for what happened down there. Look, if a guy came to me with a gun in his hand and wanted to shoot me, it would only be fair that I defend myself and try to shoot him first – this I can understand; it’s common sense, after all. But torturing, gassing, and burning elderly people, babies, and little children are things that don’t make any sense! Here’s how I found out about the gassing.

There were a number of inmates that had been there since the beginning – Jews and non-Jewish Poles who had survived since 1939 or 1940 because they were in good shape when they arrived. We, ‘the new ones’, kept complaining about the living conditions and the ‘veterans’ told us: ‘Stop whining! For the past years, you’ve been eating well at home and living a normal life.

As for us, it’s been the same ordeal every day since 1939-1940. Wait till you see the smoke from the chimneys and you’ll be thankful you’re still alive.’ On occasion, we spoke in Yiddish with them. I mean, the older inmates did – I was just a kid [and he was too young to get involved in conversations with the grown-ups].

Soon we began to lose weight… Among us, we used to call one another a ‘Muslim’ – because of the way we looked. [Editor’s note: A Muslim represents in the Eastern Europeans popular believes someone who is very skinny and starving, a term associated with African and Asian poor developed areas.] Every week there would be an inspection.

The weakest inmates were taken away. The guards used all sorts of tricks. For instance, they would claim those people were taken to a place where they would regain their strength.

Then the Poles told us where they really took them: to the gas chambers and to the crematoria. We asked those veteran fellow-inmates when we would see our parents again and their evasive reply – ‘Don’t worry, that day will come’ – made us realize the terrible truth…

The Nazis didn’t see us as human beings. They were the only ones whose idea of a shower was lethal gas instead of water. We had been ‘lucky’: when they sent us to the showers, the day of our arrival, they really poured water. But many others got the deadly gas. Inmates who had been close to the crime scene told us the horrible details.

The gas fell down from the ceiling, but it was only when it came in contact with the wet floor that the deadly reaction was unchained. When the first victims collapsed, the others began to wander around like crazy, looking for a safer spot. But no spot was safe and the doors were closed tight and locked. In the end, the room was filled by a sea of dead bodies.

The SS had selected the fittest of the inmates and formed a special squad, called Sonderkommando – I don’t know what it means. [Editor’s note: The ‘Special Squad’, also known as the ‘Death Squad’, was formed of inmates who were in charge with the asphyxiation and the cremation of the deportees; their job was to keep the gassing chambers and the crematoria running properly. Their ‘office’ lasted for four months, at the end of which they were gassed themselves by means of a new special squad.] The members of the Sonderkommando lived in a separate camp.

They were the ones who entered the gas chambers and removed the corpses using pliers and crowbars. The Sonderkommandos were divided into several groups, each with a specialized function: some removed the bodies from the gas chambers, some cut the inmates’ hair, some extracted gold teeth and removed clothes and valuables etc. Every three or six months, the Sonderkommandos were gassed themselves. I didn’t see all these things with my own eyes, mind you – I learnt about them from ex-inmates, after we had been liberated.

Work [in the factory] continued until 15 or 16 January [1945]. I later heard from others that it may have been until 15-20 January. Then things got even harder. They stopped feeding us at all. Like I said, Mendl [Eugen] and I had been in the camp together ever since we had got separated from our parents. But, in the end [in 1945], we lost track of each other. When the Russians entered Poland, the Nazis began to evacuate Auschwitz-Birkenau – I was living in Buna [also known as Auschwitz III]. They started to herd us like cattle, by the thousands. My brother and I got separated from each other in this commotion and we never saw each other again. This happened in January 1945. They took us to Mauthausen, Austria. A part of the trip was made on foot and the other part – by train.

But the Americans were closing in, so we had become a burden for the Nazis. I spent about one month in Mauthausen. They didn’t put us to work anymore. They just kept us there with no food or anything. Many others arrived in labor detachments from other camps – some of them were people I knew. For instance, my brother Gershun [Ernest]. The Hungarians had taken him to forced labor in Ukraine. From there, he somehow ended up in Mauthausen. But he didn’t recognize me. He was so sick and weakened that he wasn’t aware of who I was anymore. He was a wreck. My cousin Ludovic Blum was in a better condition – at least he recognized me. He took me by the hand and urged me to keep marching, although I was tired and desperately needed to rest. But the SS would shoot the inmates who sat down.

So we [left Mauthausen and] ended up in a forest near an Austrian town called Wels. We were totally exhausted. I weighed no more than 21 kilograms… They wanted to get it over with and kill us in that forest – they really had no use for us anymore. But we were liberated by the Americans on 5 or 6 May 1945. The GIs took us to a barracks that was turned into a sort of hospital.

The place was enclosed and guarded by sentinels, so no one could walk in or out. They gathered all the physicians they could find because we needed a special diet. Many of the inmates who could move on their own had scattered in the neighborhood. The German and Austrian civilians – we were in Austria – took pity on them and gave them food. But the poor men – who had been starving for months and years – ate too much and died because their body couldn’t deal with the unexpectedly large food intake. So the Americans confined us in that hospital and fed us small portions.

They identified the doctors and nurses among us and – regardless of the reason why they had been sent to Auschwitz – they assigned us to take care of us. It didn’t matter whether they were Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, Romanians, Gypsies or any other nation. Whoever had basic medical training was forced to attend to us.

They started feeding us diet food – I don’t know what it was, but their intelligence knew all about it. [Editor’s note: What Mr. Blum means is that the Allies possessed information about the existence of the extermination and labor camps and about the way inmates were treated in these facilities.]

Anyway, they started by giving us instant oat porridge. I stayed in that hospital until October. My brother Gershun had died in the meantime [after they had met in Mauthausen]. Ant all the others were dead too. [Mr. Blum means Margareta and Eugen.] When I checked out from that hospital, I weighed 25 kilograms.

- After the war

While we were still in hospital, they asked us: ‘Where to now?’ The American and British armies had Jewish servicemen. They wore the Star of David on their uniform and urged us to go to Israel. But I was only a kid and, like many others, said that I wanted to go back home and reunite with my family.

One day they asked us for the last time and some of us said we had to go back to Hungary – that’s where we lived [Editor’s note: At the time of the deportation, northern Transylvania belonged to Hungary.] 4. Our passports arrived and we went to Hungary, near Budapest. The country was controlled by the Americans and the Russians – each party had its own territory.

The Americans accompanied us to the Danube. The bridge had been bombed, so we crossed the river on a pontoon bridge. In Budapest we found this organization… [Editor’s note: ‘Zsidó Deportáltakat Gondozó Országos Bizottsága’ (DEGOB), an organization financed by the American Joint Distribution Committee that helped the former concentration camp inmates to return home.

The organization was located at 2 Bethlen Sq.] We didn’t stay in Budapest long – the trains had began to run again. I was accompanied by my cousin Iosif Blum and by Geza Deutsch, a friend. The three of us eventually got to Fizesul Gherlei.

We couldn’t return to our houses – they had been confiscated. The mayor had assigned three families to live in my house. My brother Matei was already in Fizesul Gherlei when we got there. He had been to our house, but hadn’t moved back in, since there was no furniture left.

None of the Jews who returned from forced labor – my brother Matei, Ludovic Feierstein, and Emanuel Abraham, who was a former fellow-inmate of my brother’s – could return to their old places, so they rented a house together and started working. My brother opened a small store. Ludovic worked as a butcher – he only slaughtered small animals, like poultry and lambs. This is how they earned their living when I found them. I moved in with them.

We didn’t get any help from anyone. We received no foreign aids. The Joint 7 only showed up in 1947 or so – but they only brought clothes, not food. The Joint was based in America. And they had no idea we needed help down there in the countryside. [Editor’s note: What Mr. Blum means is that they had to get by without the organized forms of support that were active in cities – such as the Organization of the Jewish Youth.]

Our old house had been stripped of anything. After we were gone, the village leaders took all the ‘good stuff’: furniture, clothes – which my mother poor mother had prepared for our sister’s dowry –, blankets, pillows etc.

The ‘prey’ was split among the mayor, the gendarme, and other notabilities, you see? They even held a sort of auction for a barrel. We had no one to turn to. We had no choice but to act as unkindly as those who had acted against us… But we did get our house back in the end.

After he was given the old house back, my brother Matei opened a textile store. He married a woman named Miriam in 1946. She was Jewish too. She had been born in Cluj and she was religious. They had a son whom they named Iankef, just like my father – the baby’s grandfather.

But the newly emerged communist regime didn’t seem to have abandoned persecution as a means of governing the country; they were beginning to ask questions: ‘Who are you?’, ‘What are you?’ (My father had been a tradesman and this occupation was seen very badly by the new officials.)

My brother Matei got very upset and applied for emigration. He left for Israel in 1949. That was not the best time to travel, especially if you had a small child. He couldn’t fly, so he had to embark a ship. He lived in various places and spent most of his active life as a farmer in a moshav. His last residence was in Akko. [Editor’s note: Israeli town on the shore of the Mediterranean located between Haifa and Nahariyya.] That is where he passed away in 2002. His wife had died 2 years before.

During the entire duration of the communist era, all those who didn’t want to go to the army were sent to work – a rule that applied to everyone, Jewish or non-Jewish. [Editor’s note: In the communist period, people who refused to do the military service had to do community work instead.]

There were Jews who preferred to work. But I said to myself: ‘Damn it, I had my share of work without pay!’ And I joined the army. I was in Ploiesti and Campina, both localities are situated in the South of Romania. The military service lasted 2 years. I was discharged in 1951. I did it because I was simply fed up with shoveling dirt!

When my brother Matei left for Israel with his wife and daughter, in 1949, I was already serving in the army. I made no attempt to go with him. Perhaps if I had spent more time with him and he had insisted enough, he would have persuaded me to join them… But it wasn’t the case.

After I got back from the army, I lived with Ludovic Feierstein, the butcher. With my brother gone, the house was empty [in the sense that Mr. Blum didn’t have any close relatives near him]. I got along well with Ludovic, who was much older than me. He used to have a wife, Reghina Feierstein, and a little boy, Emil, but they lost their lives in the camp. His wife was the one who lent me the cart at the time when I was working in the village, before the deportation – Ludovic had been taken to forced labor in 1942 or 1943, but his family had stayed in the village until we were all deported. Then, in 1965, Ludovic left for Israel too.

Here’s how I met my wife. I had come back from the army to Fizesul Gherlei, but there were no Jewish girls in the village anymore. As you can imagine, back then, it was considered a shame for a Jew to marry someone who wasn’t Jewish. There were cases of Jews marrying Christian girls, but they were very rare.

Nevertheless, I didn’t find the thought of spending my entire life alone appealing at all. So I found me a Christian girl. Her name was Rozalia, nee Hideg. She was born on 16 September 1933 in Fizesul Gherlei. Hungarian was her native tongue. One of her uncles was a neighbor of ours and that’s how I met her. After courting her properly, I asked her if she wanted to marry me. She said yes.

She had no income. As for me, thanks to my trade, I did have nice clothes, but that was it – I had no fortune. So I told her: ‘Take a good look at me and think it over. I have nothing except the house where I grew up.’ She was poor too, but that didn’t matter. We went to the mayor’s office and got married. We didn’t have a religious ceremony because it’s not allowed for a Jew [in case of a mixed marriage]. We got married in 1952. We’ve been together for 53 years now.

We didn’t wish to leave for Israel, unlike many Jews who emigrated. Ludovic – a cousin from Iosif’s side – was among them. They kept leaving. Commerce was on the verge of a crisis – and most of the Jews had been involved in commerce. People began to face all sorts of shortages and Jews were the first who took the blame.

We felt that we didn’t belong here anymore. Some hesitated to leave because of their children, who had been raised here. But the same children also gave them a pretty good reason to leave – because there was no future for them here anymore.

Besides, many Jews wanted to keep the faith alive and were aware that interethnic marriages would cause the faith to fade away… [Editor’s note: With the Jewish population dramatically diminishing, religious Jews thought it was a moral duty to emigrate to Israel in order to avoid interethnic marriages.]

So I was left alone [without his brother and his brother’s friend]. I just didn’t go and that’s that! No point in discussing this. Before, we weren’t allowed to bury goyim in our cemetery. But look at people like my wife and me: we’ve been together for so many years.

So the rabbinate gave a decree that allowed it. Apart from that, the Jewish religion is still very strict. If it weren’t so, it would vanish. I don’t mean to sound patriotic or something – I’m just a country boy who never got further than 7th grade –, but here it goes: when you think of all the religions that disappeared over the centuries, you can’t but wonder at how the Jewish faith survived – even scattered in the four corners of the world.

I owned horses and a cart until 1962. I worked as a wagoner. I was also a bit of a butcher, but I was soon forbidden to work on my own – the State became the owner of everything 8. So I relied on my cart. Peasants would need to have a lamb slaughtered from time to time.

I took care of this, bought the hide, and took it to the authorities. They paid me and I, in my turn, paid the peasants for the hide. I had to deliver 150 hides. I did the slaughtering on Sunday and delivered the hides on Monday morning. When cars began to appear, I knew my cart had lived its days.

There was little left for me to do in my village, so I threw away my cart and started looking for another job. My friends found me a position at the sausage factory [in Gherla]. Two of their employees had been drafted, so there was an opening. They hired me as an untrained worker in 1959.

That was only fair, since I had no education except my 7 grades. When I came back [after World War II], I made no attempt to continue my education. When I moved to Gherla, I had already been working in the factory for some time. From 1959 to 1962 I commuted by bike from Fizesul Gherlei to Gherla.

The road had no asphalt. This was also true for the town proper, where streets were paved with stones, not covered with asphalt. The commute became a pain in the neck – I worked till late and got home close to midnight or even after midnight. So we decided to move to Gherla, which we did in 1962. We sold my parents’ house in the village and built this one over here.

When we moved in, it had no doors or windows. At first, we occupied a single room that we had fitted with windows. It took three years to finish the house – I was just a worker and didn’t have money… I spent 20 more years or so working in the sausage factory.

In the end, I was transferred to a butcher’s shop. Here’s how it happened. The Hungarian Jew who worked as a butcher in this State-owned consumption cooperative [Editor’s note: In the communist era, the service industry was dominated by the system of ‘consumption and credit cooperatives’, thousands of distinct State-owned ‘business units’ that activated in fields such as: retail, production, services, restaurants and tourism, wholesale trade with food, credits. These cooperatives formed Centrocoop (The Central Union of Consumption Cooperatives), a gigantic, centralized, State-controlled organization founded in 1950.] applied for emigration to Israel. The manager of the cooperative came to our factory to look for a new butcher.

My boss recommended me. I was just a worker, but my boss thought I would be good for that job. The problem was that the job came with greater responsibility: I was supposed to do bookkeeping too. So the manager of the butcher’s shop had to get the Party’s approval to hire me. [Editor’s note: Getting the Party’s approval for a transfer was a practically unavoidable step in a highly centralized, bureaucratic, State-owned, and Party-controlled economy.] My work schedule improved: 8 hours a day. For instance, at the factory, I was used to working until I finished my task, not according to a fixed schedule… I spent 32 years in this butcher’s shop. I was the one who kept the keys – my boss trusted me a lot. I retired in 1991.

I never had any problems at work because I was a Jew or because I had a brother who lived in Israel. After all, I was a simple worker… Had I held a higher position – like clerk – or had I been working for the Party, things may have been different. I never tried to hide my faith. When my coworkers saw me come, they would say ‘Here comes the jidan’. [Editor’s note: ‘Jidan’ is usually a derogatory term for Jew in Romanian, but, in this particular context it is used as a familiar and even kind appellation.]

But I didn’t mind; on the contrary I would admit it: ‘Yes, it’s true, I am a jidan’. Besides, they didn’t mean it as an insult, you know. In these parts, we don’t say ‘Jew’, but ‘jidan’. It wasn’t pejorative or anything. On occasion, my coworkers asked me to tell them stories from my deportation days.

Being a Jew is not easy. [Editor’s note: Mr. Blum often uses this expression in Yiddish. To illustrate it, he tells the following story.] There was a Jew in Gherla. His name was Bela Stein and he used to be a printer before the deportation. His father made kosher cheese and employed several Jews who milked sheep for him.

The entire family was deported. Bela Stein survived. When he came back he began the formalities to take the land of his family back. By 1946, he had got his properties back. But he couldn’t enjoy them for long: in 1948 the regime confiscated them again and sent him to the Canal, like all the other kulaks 9. [Editor’s note: In 1949 began the construction of the Danube-Black Sea Canal. Many of the workers were political prisoners from the communist jails. Work came to a halt in 1955, only to be resumed in 1975 and completed in 1984.

The Canal starts south of the town of Cernavoda and ends in Agigea, south of the city of Constanta. It connects the Danube to the Black Sea and cuts down the way to the sea with almost 400 kilometers.] The new regime finished the job of the Nazis and Hungarians: those who had escaped the Holocaust were deported by the Communists and ended up at the Canal. [Editor’s note: This must not be taken as a general truth; this is Mr. Blum’s generalization.] Stein only got away after friends of his from the US made pressures on the Romanian government. He left for Israel.

This wasn’t the only in which a Jew was released as a result of foreign pressure. For instance, there was another Jew from Dej who used to trade cattle… I don’t know what they had against him, but they put him in jail. In his days as a cattle trader, he had helped a shochet with kosher meat. That shochet, who had fled to America when the Communists came to power, went to our embassy in the US and arranged for the trader to be released.

I want to stress out that a destitute peasant had a far easier time than us. No one picked on him – they just let him live his petty life. But Jews were under constant suspicion. Think of that trial that took place in Hungary, before World War I [Editor’s note: Mr. Blum refers to the Tiszaeszlar trial.] 10 Jews were accused of using Christian blood when making matzah. That’s no story. It’s an accusation that has been inflicted on Jews since I don’t know when. Or think of the Dreyfus trial 11.

As a Jew, these things grieve me. But what about them? They killed my parents and my siblings. Isn’t that a shame for all mankind? No matter what they give me in compensation, they cannot redeem themselves. I may say I forgive them, but my heart will never forget what they did. Think of those who move to another faith… How can they do that? Don’t they think of their mother and father, who are in Heaven? What would they say if they knew their offspring gave up the faith they were born into? It’s the same with Jews.

Once a Jew, always a Jew! You can’t turn a Jew into a Catholic. Similarly, a Christian will never become a Jew, even if he formally converts to Judaism. We must be true to the faith we were born into. I told my daughter: ‘You tell everyone that you come from a Jewish father and a Hungarian mother. Whether they accept you or not – that’s their problem!’

The friends we had in Gherla were Jews, Hungarians, and Romanians. We used to visit the Jewish ones especially on Purim, when we exchanged the traditional cakes. When I was little, I would go around with cakes more often than after the war.

All these troubles caused some of the faith to be lost… But a rabbi said: ‘In the middle of all this cruelty, turn not to God, but to Man, for he is the one responsible.’ [Editor’s note: This phrase can be heard on the occasion of the Holocaust commemorations. Mr. Blum may have heard it from Liviu Beris, survivor of Transnistria, vice-president of the Romanian Holocaust Survivors’ Association.]

As a Jew, I always felt a bit fearful... I kept to myself more than others. I did play with other kids, but I hesitated before going to the teacher’s or to the priest’s house… I think I was born with this. I was fearful under the communist regime too. Did I have faith that things would get better after the war?

When I came back from deportation, no one welcomed me with open arms. There were some who said ‘The poor man, he has returned… Let’s give him a slice of bread.’ But there were others who thought ‘He should’ve stayed there!’ That’s why I say there are two kinds of people in the world: good and bad. I experienced this first hand. It’s true, I was a bit of a coward in the sense that I didn’t go after the ones who took away our things while we were gone.

But my brother spotted a guy who was using a pair of scales that had belonged to our store – back then, this was a valuable item, especially if you were penniless. The guy wouldn’t give it back, so my brother took his case in front of the mayor. Eventually, the man was forced to return the pair of scales.

My brother didn’t get involved in politics at all. That’s why he left. As for me, I didn’t care about Communism. I just did my job and cashed my paycheck. That was all. Let me tell you something: Communism wasn’t meant to be a dictatorship. It was supposed to be a form of socialism: if one has the right to own 100 hectares or a factory, the workers, in their turn, should have the right to say ‘Look, I won’t work for 1 leu, but for 5 because that’s how much I worth.’

This is what Socialism is about. I accidentally became a member of the U.T.M. [The Union of the Working Youth], but it did me good. I may have attended one or two meetings, but I never said a word. When they drafted me, they sent me to the school for instructors. Back in 1949 the army needed to create new officers. Everyone who had the right social origin could end up in the officers’ academy in Brasov.

My own social origin was a bit tricky. The ‘good’ part was that I was a Jew and my parents had been poor. The ‘bad’ part was that my father had been a tradesman and I had a brother in Israel. Still, they were willing to send me to the officers’ academy, but I declined. I chose the school for instructors instead. I was an artillery instructor and I was in command of three canons.

You see, I’m telling you things as they come to my mind – good or bad. My daughter, for instance, wanted to go to college and study cybernetics. I gave her money to go to Bucharest, but she brought it back: they had given her a scholarship.

She would come home once a month and I would wait for her at the airport. And now I’m asking you: could a worker’s afford college today? I have lived under four or five different regimes – and every one of them had good things and bad things. Take Communism, for instance. If the Russians hadn’t come, what would have become of all of us?

We would have ended up in the ovens! One should not condemn a certain regime, but the individuals who do bad things. The ones who do good things should be praised and the ones who do bad things should be eliminated.

Our only daughter, Berta, was born in 1955. She went to college in Bucharest and got a degree in economic cybernetics. She is not ‘officially’ Jewish – according to the Jewish tradition, you are a Jew only if your mother is Jewish. However, we registered her as Jewish in school. She now lives and works in Oradea.

She’s married to Francisc, a man who has both Romanian and Hungarian origins. Her surname as a married woman is Marian. They both have decent jobs, but they’re not rich or anything… My daughter thinks of herself as Jewish. She has a son, Petrisor, who has just graduated from college. He’s into commerce, just like his mother. She raised him as a Jew.

One more thing about the deportation. Speaking of the Righteous among the Nations… There were priests who said ‘What are you doing to these people?’ But there were also priests who said ‘Take them away, they don’t have the same faith as we do!’ That’s why I say that a man’s soul is his true religion.

I may not be an educated man, but you should take my word for it! One must respect other human beings, regardless of their differences. Think of the Ten Commandments. People who have lost their parents can at least visit their tombs. But what about us Jews? Where can we go to mourn our parents? In Heaven?! They turned them to ashes – and that’s a terrible crime.

After I came back from deportation, I didn’t observe all the religious tratisions. I have to admit I didn’t keep the kashrut, for instance. Since there weren’t enough Jews for a minyan in Fizesul Gherlei anymore, I came to Gherla for the high holidays: Purim, Pesach, Yom Kippur, and Rosh Hashanah.

But I didn’t keep the Sabbath as a holiday – I worked on Saturday… That was a sin. I did recite the Kaddish for my parents though. Now I’m the only Jew left in Gherla. I always go to Dej or Cluj for the high holidays. And I fast.

- Glossary:

1 Constitution of 1923: After the foundation of the modern Romanian state the problems of citizenship and civil rights of the Jewish community were largely debated, although this issue was not included in the first Constitution of 1866. After the Congress of Berlin in 1878, this problem became an issue of constitutional law.

During World War I several great changes were put on board, such as the new electoral system, the land reform and the extension of civil rights. They formed the main axis of the new Constitution of 1923, which allowed the Jewish community of Romania to receive Romanian citizenship.

2 Hungarian era (1940-1944): The expression Hungarian era refers to the period between 30 August 1940 - 15 October 1944 in Transylvania. As a result of the Trianon peace treaties in 1920 the eastern part of Hungary (Maramures, Crisana, Banat, Transylvania) was annexed to Romania. Two million inhabitants of Hungarian nationality came under Romanian rule.

In the summer of 1940, under pressure from Berlin and Rome, the Romanian government agreed to return Northern Transylvania, where the majority of the Hungarians lived, to Hungary. The anti-Jewish laws introduced in 1938 and 1939 in Hungary were also applied in Northern Transylvania.

Following the German occupation of Hungary on 19th March 1944, Jews from Northern Transylvania were deported to and killed in concentration camps along with Jews from all over Hungary except for Budapest. Northern Transylvania belonged to Hungary until the fall of 1944, when the Soviet troops entered and introduced a regime of military administration that sustained local autonomy.

The military administration ended on 9th March 1945 when the Romanian administration was reintroduced in all the Western territories lost in 1940.

3 Goga-Cuza government: Anti-Jewish and chauvinist government established in 1937, led by Octavian Goga, poet and Romanian nationalist, and Alexandru C. Cuza, professor of the University of Iasi, and well known for its radical anti-Semitic view.

Goga and Cuza were the leaders of the National Christian Party, an extremist right-wing organization founded in 1935. After the elections of 1937 the Romanian king, Carol II, appointed the National Christian Party to form a minority government.

The Goga-Cuza government had radically limited the rights of the Jewish population during their short rule; they barred Jews from the civil service and army and forbade them to buy property and practice certain professions. In February 1938 King Carol established a royal dictatorship. He suspended the Constitution of 1923 and introduced a new constitution that concentrated all legislative and executive powers in his hands, gave him total control over the judicial system and the press, and introduced a one-party system.

4 Second Vienna Dictate: The Romanian and Hungarian governments carried on negotiations about the territorial partition of Transylvania in August 1940. Due to their conflict of interests, the negotiations turned out to be fruitless. In order to avoid violent conflict a German-Italian court of arbitration was set up, following Hitler’s directives, which was also accepted by the parties.

The verdict was pronounced on 30th August 1940 in Vienna: Hungary got back a territory of 43,000 km² with 2,5 million inhabitants. This territory (Northern Transylvania, Seklerland) was populated mainly by Hungarians (52% according to the Hungarian census and 38% according to the Romanian one) but at the same time more than 1 million Romanians got under the authority of Hungary.

Although Romania had 19 days for capitulation, the Hungarian troops entered Transylvania on 5th September. The verdict was disapproved by several Western European countries and the US; the UK considered it a forced dictate and refused to recognize its validity.

5 Yellow star in Hungary: In a decree introduced on 31st March 1944 the Sztojay government obliged all persons older than 6 years qualified as Jews, according to the relevant laws, to wear, starting from 5th April, “outside the house” a 10x10 cm, canary yellow colored star made of textile, silk or velvet, sewed onto the left side of their clothes.

The government of Dome Sztojay, appointed due to the German invasion, emitted dozens of decrees aiming at the separation, isolation and despoilment of the Jewish population, all this preparing and facilitating deportation. These decrees prohibited persons qualified as Jews from owning and using telephones, radios, cars, and from changing domicile.

They prohibited the employment of non-Jewish persons in households qualified as Jewish, ordered the dismissal of public employees qualified as Jews, and introduced many other restrictions and prohibitions. The obligation to wear a yellow star aimed at the visible distinction of persons qualified as Jews, and made possible from the beginning abuses by the police and gendarmes.

A few categories were exempted from this obligation: WWI invalids and awarded veterans, respectively following the pressure of the Christian Church priests, the widows and orphans of awarded WWI heroes, WWII orphans and widows, converted Jews married to a Christian and foreigners. (Randolph L. Braham: A nepirtas politikaja, A holokauszt Magyarorszagon / The Politics of Genocide, The Holocaust in Hungary, Budapest, Uj Mandatum, 2003, p. 89–90.)

6 The Levente movement: Institution set up for the promotion of religious and national education, respectively physical training. All boys between 12 and 21, who didn’t attend a school providing regular physical education or who didn’t actually do a military service were forced to join it.

Since the Treaty of Versailles forbade Hungary to enforce the general obligations related to national defense, the Levente movement aimed at its substitution as well, as its members not only participated at sports activities and marches during weekends, but practiced the use of weapons too, under the guidance of demobilized officers on actual service or reserve officers.

(The Law no. II of 1939 on National Defense made compulsory the national defense education and the joining of the movement.) (Ignac Romsics: Magyarorszag tortenete a XX. szazadban/The History of Hungary in the 20th Century, Budapest, Osiris Publishing House, 2002, p. 181-182.)

7 Joint (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee): The Joint was formed in 1914 with the fusion of three American Jewish committees of assistance, which were alarmed by the suffering of Jews during WWI. In late 1944, the Joint entered Europe’s liberated areas and organized a massive relief operation.

It provided food for Jewish survivors all over Europe, it supplied clothing, books and school supplies for children. It supported cultural amenities and brought religious supplies for the Jewish communities. The Joint also operated DP camps, in which it organized retraining programs to help people learn trades that would enable them to earn a living, while its cultural and religious activities helped re-establish Jewish life.

The Joint was also closely involved in helping Jews to emigrate from Europe and from Muslim countries. The Joint was expelled from East Central Europe for decades during the Cold War and it has only come back to many of these countries after the fall of communism. Today the Joint provides social welfare programs for elderly Holocaust survivors and encourages Jewish renewal and communal development.

8 Nationalization in Romania: The nationalization of industry and natural resources in Romania was laid down by the law of 11th June 1948. It was correlated with the forced collectivization of agriculture and the introduction of planned economy.