Jerzy Pikielny

Warsaw

Poland

Interviewer: Kinga Galuszka

Date of interview: February-June 2005

My interviewee lives with his wife, Nina Barylko-Pikielna, in a beautiful apartment, full of light and filled with books. I recorded Mr. Pikielny's story in the course of four meetings. Later we met another couple of times to put the tale together. Fortunately, Mr. Pikielny found the time for reminiscing, although he's still an active and constantly busy person. Throughout our conversations he would modestly maintain his stories were not going to charm anyone. Everything he'd say, however, would form a surprisingly considered history of the Drutowski and Pikielny families of pre-war Lodz. I'd like to emphasize, in accordance with Mr. Pikielny's wish, that he gathered much of the information given here from other people, and that he never met some members of the family he talks about.

I remember Grandma and Grandpa Drutowski, my mother's parents, well. I was their single, beloved grandchild and that gave me, of course, many privileges. I often went to see them and stayed the night. Grandma and Grandpa were wholly assimilated. I don't recall them observing the Jewish traditions.

Grandpa's name was Maurycy Drutowski, son of Samuel. He was born in 1869 in Czestochowa as Moszek, but he always used the name Maurycy. He went to a Russian school. His hometown, Czestochowa, was under Russian rule at the time 1. It wasn't a Jewish school but a state-run one, and with a classical curriculum, with Greek and Latin classes. Grandpa, according to his own words, was, however, a very good mathematician. After graduation he studied in Zurich, Switzerland, at the technical university there, and graduated as a mechanical engineer. It was there he met his future wife, my grandmother, who lived in Zurich at a boarding school for young ladies. When he arrived in Lodz Grandpa started work at Rosenblat's Cotton Garments Factory on Karol Street, now Zwirki [the building still exists, at no. 36], as head of the mechanical department.

In 1908 Grandpa Maurycy and his brother-in-law Jozef, whom he'd had come to Lodz, opened the Drutowski & Imass Mechanical Repair Workshop at 255 Piotrkowska Street. On 11th April 1924 the company was renamed the Drutowski & Imass Electric Appliances Factory. They manufactured things including electric meters, which were widely used in Lodz. That I can confirm myself, because I worked as an electrician in the ghetto, and while it was usually repairing engines in the workshop, I did sometimes find those meters in people's apartments. At the 1929 Universal National Exposition in Poznan the company received two silver medals. Simultaneously the partners ran a technical office at 111 Piotrkowska Street. Following some arguments with his brother-in-law Grandpa left the company in March 1931.

As far back as I can remember, Grandpa never actually had a job. He was, however, an active expert for the Polish Mechanical Engineers' Association [SIMP], an expert legal witness in the fields of mechanics and technical appliances, and a member of that Association [details taken from the biographical dictionary Zydzi dawnej Lodzi (Jews of Old Lodz), Lodz 2004, vol. 4].

Grandpa was quite tall, and he had a moustache. He was often mistaken for a nobleman because of his dignified appearance, that and his name of course. Grandpa liked to play bridge very much. He used to go to a café next to our house at 8 Nawrot Street. The café was located on the corner of Piotrkowska and Nawrot streets and was the property of Mr. Piatkowski. Grandpa had a seat kept for him there. Everyone knew you could always meet him there, or telephone and ask the waiter, 'Is Mr. Drutowski there?' I remember going there with him. He'd drink his small latte and I'd have a cream filled meringue. Grandpa was always spoiling me and was very proud of me. Grandpa also had good relations with the streetcar drivers. A streetcar would approach the house on Radwanska Street, slow to a stop, and Grandpa would step out. He knew how to talk with the drivers.

Grandpa had a brother, Emanuel, who lived in Lodz, too. Emanuel was a banker, and he lived in a residential quarter of Lodz which was called Jordanow in pre-war times and Orchideen Park under the Germans. He had a son and a daughter; she did a degree in hotelliery. I don't remember their names. I don't know what happened to any of them. We heard, but I don't know if it's true, that Emanuel's son was in Lwow as the Germans marched in. Someone told us he leaped from the column and started to shoot at the Germans. And so they killed him. I didn't know any other relatives from my grandfather's side.

Grandma's name was Aniuta, nee Imass. She was from Chisinau [now the capital of Moldova]. She was born in 1877 - she was eight years younger than Grandpa. My grandparents settled in Lodz after they got married. Their last apartment was at 25 Radwanska Street. They had two children: a daughter named Czeslawa, my mother, born in 1897, and a son named Leon, born in 1899.

Grandma was rather small, quite thin, you could call her petite. Perhaps it had something to do with the angina pectoris she suffered from. Apart from the education she'd earned in Switzerland she didn't go to any school. She never worked. She told me that in 1905 2 there was a great demonstration in Lodz which the Cossacks were dispersing, and so Grandma went there to take part in it, against the Cossacks naturally. She didn't have to go, her status did not force her to fight and protest.

Grandma Drutowska had a heart condition all her life and for that reason I didn't have such good relations with her as with Grandpa. She had a brother named Jozef, whom Grandpa had come to Lodz from Chisinau. I remember I met him once at an ice-skating rink. We even talked. I see the way he looked as I close my eyes. He was a bit younger than Grandma, not too tall, plump. As for Grandma, I cannot say anything more about her.

I don't know if my grandparents spoke Yiddish. They were a wholly assimilated, non-religious family. I know for sure that in the ghetto Grandpa would still recite Greek poems he'd learned at school. I never heard them speak Yiddish, though. We never used that language at our home either.

I only remember one of my grandparents' apartments, the last one, on Radwanska Street. They'd lived on Andrzeja Street before that. Tuwim 3, whom my mother knew personally, lived nearby. The last house was new, they had radiators there, which was a sign of modernity. There was a sizable collection of books at Grandma and Grandpa Drutowskis'. They had the collected plays of Fredro [Aleksander Fredro (1793-1876): author of comedies of manners depicting the life of Polish provincial gentry]. They had a dog for a while, a German shepherd called Lot. But later Grandpa gave it to some forester.

Grandpa died in the Lodz ghetto 4 on 1st April 1942 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery on Bracka Street. Ghetto Jews were buried in a specially allotted part of the cemetery but my grandparents are buried outside that area - I don't know why. I don't remember the cause of his death but he'd probably got pneumonia, and he also suffered from Graves-Basedow disease [overactive thyroid]. The more important cause of his death was, however, the fact Grandma had died a year earlier and he couldn't bear it.

My grandparents' son Leon we nicknamed Lolek. He was two years younger than my mom. He was born in 1899 in Lodz. As soon as the Legions 5 were formed, Lolek, who was still underage, ran away to the army and so Grandpa went to look for him. He found him brushing horses in some unit. Lolek was a co-founder of the Polish scouting organization in Lodz. The troop was named after Tadeusz Kosciuszko 6 and Lolek was its scoutmaster. He probably served in the army in the 1920s.

First he studied at Warsaw University of Technology and later at the mechanical and electrical faculty in Liege, Belgium. After graduation he returned for a short time and started to work at his father and uncle's factory. But, just like his father, Lolek didn't get on well with Uncle Jozef and soon went back to Belgium.

In Belgium he met his first wife, Dennise. At first he worked in Cologne, Germany, and commuted there from Liege by motorbike every week, coming back home for Sundays. Every time he crossed the German-Belgian border the Germans would halt him and order a personal search. He said that later he'd head straight for the control point himself. Later on Lolek owned an oil boiler factory in Belgium.

After the outbreak of the war he left Belgium and lived somewhere in France, in the unoccupied zone [central and southern France, including the Mediterranean coast, was unoccupied]. His departure was partly caused by the fact that Dennise's family strongly opposed their marriage, mainly because of his Jewish origins - something which I learned of from Uncle Lolek's second wife. Lolek was only intending to be away for a short time. Apparently, when he returned in 1944 or 1945 Dennise was already with someone else. He remarried upon returning to Poland in 1947. His wife's name was Maria Kazimiera, nee Kuras. That aunt is not Jewish either. She was born on 7th May 1914. Now she's partly paralyzed and lives in the Matysiaki Old People's Home in Warsaw.

After returning to Lodz, Lolek started work at the Military Automotive Works. A few years later he was transferred to the Ministry of Light Industry and Crafts. That's when he and his wife moved to Warsaw. Later he worked in one of the Ministry's institutes. He died in 1964.

My mother, Czeslawa, was born in 1897. She went to a girls' gymnasium in Lodz. She wanted to enroll in a university but Grandpa wouldn't allow it. I know Mom was musically gifted, she used to sing and play the piano back before her marriage.

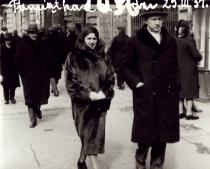

My mom loved traveling. She went to Palestine with my father in 1930- something, I'm sure she went to Venice as well. She led quite an active life. Mom told me an anecdote once: apparently I told a teacher I had to be independent, because if I waited for Mom to get home and help me do my homework, I'd never do anything. She had her favorite café - on the corner of Piotrkowska and Moniuszki streets - which she used to go to almost everyday. She'd meet her friends there, but unfortunately I don't remember any of them.

My paternal great-grandfather was called Todres Pikielny. He apparently lived in Navahrudak [now Belarus]. He had six sons and three daughters. The sons were called Abram, that's my granddad, Izaak, Jochel, Tobias, Mojzesz, and Markus. The daughters were Rachela, Merka, and Sara. I didn't know most of that family before the war. The information I'm giving here was gathered later.

All I know about Izaak is that all of his family perished during the Holocaust. Jochel was born in 1886. He owned a factory. His wife's name was Chaja Cyrla, she was born in the same year as her husband. They had three children. The daughters were Mina, born in 1896, and Erlora, born in 1898. Their son, Symcha, was born in 1892. They were all killed in the Holocaust.

Abram, my grandpa that is, and his brother Jochel launched a manufacturing company, which operated in Lodz up till 1927 under the name Jochel Pikielny & Heirs to Abram Pikielny. That same year, the A. & J. Pikielny Textile Industry Joint-Stock Company was established in Lodz. It was to incorporate all the assets and debts and continue the first company's operations. A branch of the company was opened in 1928 in Zdunska Wola [50 km south of Lodz]. My father's brother Henryk was the manager of that factory.

Mojzesz was born on 25th May 1869 in Yeremiche. He had a twin brother, Tobias, who died before the war. In 1889 Mojzesz settled in Lodz, where he and his brother-in-law manufactured part-silk handkerchiefs, and after that he founded a wool weaving mill with Tobias, which was later transformed into M. & T. Pikielny, Inc. His grandson, Henryk, the son of his son Maks, known in the family as Henio, a citizen of Brazil, recently filed a lawsuit against the Polish state to reclaim the factory. [Editor's note: Jews of Polish descent have the right to seek restitution of property nationalized by the Polish state after 1945.]

Mojzesz had two sons and two daughters. The elder son, Maks, was born on 22nd January 1899 in Lodz. His wife, Fryda - I don't remember her surname - came from Riga [today Latvia]. Maks and Fryda had two sons, Henio and Serge. Before the war we lived in the same house, at 8 Nawrot Street, us on the third floor and them on the fourth. I was very good friends with Henio. Mojzesz' other son was called William. He was born in 1903 and he died in a bombing in eastern Poland in 1939. His daughters were called Betty and Hala.

Tobias had three children; two sons: Jozef, who emigrated to Argentina, and Herman. His daughter's name was Frania. She married Izaak Hochmann. Shortly before the war the Hochmanns moved to Brazil. Frania had a daughter, Iza, and a son, Aleksander.

My grandparents' other son was Markus. He and his wife were in the Warsaw ghetto 7. They had two children. The son, Robert, was a painter. He lived in Paris from 1923 and he also died there after the war. The daughter's name was Lili. She was in the ghetto with her family and they managed to get through to the 'Aryan side.' They moved to the USA after the war and later to France, where they died.

I learned from Iza de Neyman, my Grandpa's niece, whom I met after the war, that Merka, her mother, married Aron Lusternik. They had several children. Their son Lazar was a famous mathematician. Some of that family left Lodz and moved to Russia during World War I. Lazar stayed there, and lived in the Soviet Union all his life. The other sons were called Anatol and Maks. The daughters were Roma, Roza, Helena, Iza, and Anna.

Iza's married name after her first marriage was Klein. She was an actress, performing under the stage name Iza Falenska. During the war she was in hiding in Warsaw on the so-called 'Aryan side.' After the war she moved to France; she lived in Paris at first and later moved to Nice. There she met and married Stanislaw de Neyman, who'd been the Polish representative in the League of Nations 8. Iza died in Nice around 1990.

Anna lived in Lodz before World War II. During the war she was in the Warsaw ghetto with her family, but they managed to get out to the 'Aryan side.' In January 1945 they moved to Lodz. In 1968 they emigrated to France, where they died.

Sara, another of my great-grandparents' daughters, had three children. Her eldest son, Jozef, emigrated to France in the 1920s. After World War II he married Merka's daughter Roza, and after her death they left for Israel. They couldn't emigrate before that because Roza couldn't bear the climate. Jozef died in Israel. Sara's second child, a daughter, Ala, moved to France in the 1920s just like her brother and died there, long after the war. Sara's youngest son was called Moniek, he lived and died in Israel.

My [paternal] grandfather was called Abram. He was born in 1865 in Yeremiche [today Belarus]. Grandpa Pikielny died in 1923, that is, before I was born. From what I've heard he had his brothers come from the Navahrudak area to Lodz. Grandma's name was Sara. As far as I know she was the only one in our family to observe the kosher rules. I remember going with her at the high holidays to the synagogue on Kosciuszki Street - the Germans burned it down immediately after taking Lodz - to the women's part of it of course. I don't know how Grandma died. I was only told she sold cookies in the streets of the Warsaw ghetto, just to get by.

My grandparents had at least three daughters and at least three sons. They were all married and had children. One daughter, my father's sister, was called Estera. She was born in 1893. She lived in Paris back before the war. Her husband was Mané-Katz 9. They didn't have kids, and parted back before the war.

Estera's second husband was an art critic named Pawel Barchan. He died in a concentration camp during the war. She survived. I kept in better contact with her after the war than before it. Estera was a painter. She was known as Estera Barchan. Unfortunately, she lost her sight later. She died in November 1990. She was buried in the cemetery in Levalois near Paris.

My father's second sister was called Raja. She married Leon Szyfman, who was a doctor in Lodz. He was drafted into the army in 1939. He was held POW in an Oflag 10, and that probably saved him his life. After the war he moved to Paris for some time but soon left for Israel. He was a Zionist even before the war.

Raja and Leon had two daughters, Niusia and Inia. They were slightly older than me. In 1962, Szyfman published a book in Israel, in Hebrew: 'Got My Whole Life Ahead.' It contained translations of the letters his daughters wrote him during his Oflag imprisonment. Leon had suffered from depression before the war, and they tried to lift his spirits by writing him. There's a Xerox of one of the letters and a card sent from Poniatow [about 35 km from Warsaw]. Here's a fragment of a letter written 9th August 1940: 'We're sending our beloved Daddy a photo of us playing volleyball. My face is in the shadow, and Inia is standing in the middle. We kiss your little nose, moustache and those sweet eyes of yours. We're outside our house on the corner of Zielna and Chmielna.' That means they certainly were in the Warsaw ghetto by then.

The last letter was sent from Poniatow, I guess. Szyfman's daughters wrote: 'Dearest, beloved Daddy, we received a card from you yesterday, and a letter a couple of days ago. I haven't written from here yet as we didn't have the forms, and it's forbidden to write too much anyway. We live in a room together with Stefania [a lady whom the girls knew].' I don't know who this Stefania was. Not everything in these letters is clear to me anyway. 'We have very good conditions here. Stefania is very kind to us, she's really sweet. We'd love it if you could drop her a line or two. We're healthy, we work, and it's really very good here. The countryside is beautiful, woods, fields, and meadows. We hope for the best and we're filled with faith, just hold on, Daddy, and believe we're going to be together, all of us. Lots of kisses, your longing Inia.'

'Beloved, sweetest Daddy-pie, today I got yet another letter from you. Sending letters is a bit tricky here. So don't you be upset by the frequent lack of news. It's much better for us here than in Warsaw. The living conditions are great, we're very well fed. Trust us, we're strong, and hope for the best. Our health is good and spirits high. Daddy, I'm not making this up just to put your mind at ease, promise. I've got my whole life ahead. I have lots of energy today to fight and the health to enjoy it. I want to get letters from you that are not sad, that are full of anxiety, but also of strength and hope. We'll build us a life, come what may. Waiting for your letter, your N.' [Mr. Pikielny knows the letters from the book 'Got My Whole Life Ahead.' There were facsimiles of the Polish originals in it, too.]

Iza de Neyman, whom I've already mentioned, told me about Niusia and Inia. She said there was a chance to get them out of the camp. Someone who came to take them decided he could only get one of them out, otherwise the risk would be too great. They refused. And they both died. One of my cousins reported that to Yad Vashem 11, told them about their solidarity. He informed them that the girls were killed in the Lodz ghetto and that's not true. They'd never been there. I don't know where Raja and her daughters died.

My father's sister Frania was born on 8th September 1894, and her married name was Stuczynska. She lived in Vilnius with her husband. They had a daughter, my age, called Lidia. She was probably born in Vilnius, on 15th December 1926. All of Frania's family was in the Vilnius ghetto 12, from where they were transferred to one of the camps in Lithuania and were killed there.

One of my grandparents' sons was called Henryk. He lived in Zdunska Wola, he ran the A. & J. Pikielny factory founded by Grandpa. His wife's maiden name was Mazo. I don't remember her first name. They had two sons. Romek, who was older than me, went to a Hebrew gymnasium in Lodz; he commuted there every day from Zdunska Wola. All of Henryk's family was killed. They say Romek was in a camp somewhere. He went outside a building and there was standing an SS-man who said he had to kill the first Jew he saw. And unfortunately Romek was that first one.

My grandparents' third son was called Maks. He had two sons. The elder one's name was Alek. I remember him being unhappy with the fact he'd been born during the summer vacation and so couldn't throw a birthday party. He had his bar mitzvah in 1939. I think the second son was called Bronek. I've heard Maks's family was in the Warsaw ghetto at first. They all died.

My father's name was Lazar. We called him Ludwik at home. He was born in 1890. He was very musically gifted and even wanted to become a conductor, but for sheer practical reasons ended up a doctor. I think he studied in Vienna, Austria. He worked at the Poznanskich Hospital on the street that's nowadays called Szterlinga. He was a urologist but since there was no separate urology ward at the time, his patients were treated in the surgical ward.

Some of the information I have about my father comes from the book 'The Martyrdom of Jewish Physicians in Poland,' published in the USA by the doctors Malowist, Lazarowicz, and Tennenbaum. The authors say my father got his diploma in 1925. Father used to write articles on medical issues for various magazines. He worked mostly in a Jewish environment so I'm pretty sure he spoke Yiddish.

Father met my mother thanks to his cousin, whom Mother went to school with and was close to. The young couple lived in Lodz on 8 Nawrot Street. That's the fourth house counting from Piotrkowska Street [Lodz's main street]. There were five rooms in the apartment. Father had his office there and he saw his patients in it. All the rooms were so spacious I could ride my bike indoors.

I was born in 1926. I didn't go to school until third grade because I was always ill, I often had bronchitis. At first I went to a private co- educational school called 'Our School.' Most of the students were Jewish. Two Jewish women ran it. We had teas with our class tutor in her apartment. We spoke with her about almost everything. I don't remember her name, unfortunately. At 'Our School' we spoke freely with the teachers about the opposite sex, something unthinkable at the all-male school I later attended.

Naturally, the classes at 'Our School' were given in Polish. There were religion classes, which dealt mainly with Jewish history. I don't remember the names of the teachers. I do remember some of my classmates, though. One of them, younger than me, was Tadeusz Noskowicz. We didn't know each other while at school, it was only after the war that we met and realized we'd attended the same school. Tadeusz emigrated in 1968 13, he settled in Sweden and worked as a doctor there.

Another one was called Manfred Sawicki. He was born in Germany but in, I think, 1938 the Germans deported all the Jews with Polish citizenship to Poland 14. He came to Poland with his whole family. Manfred moved to South America after the war. We had a classmate we were all in love with, Jola Potaznikow. I know she was in the ghetto and then probably in Terezin 15, where she met a boy, a Czech, whom she married after the war. Unfortunately, she died giving birth to her child shortly after the war. There were also this brother and sister, Zosia and Michal Linde. She was in my class and he was a grade higher. They both survived in the USSR.

From sixth grade on I attended an elementary school which was part of a boys' gymnasium. It was known as 'The Communal Gymnasium.' The school was located at 105 Pomorska Street. Boys of different denominations attended it. I was already aware of the differences between that and my former school. The main one was the relationship between teachers and students, which was not as casual at the gymnasium.

I remember a classmate from that school, Tadzik Tempelhof, who lives outside Poland today. He spent the war in the USSR. After finishing his studies he moved to Australia with his wife and son, but they couldn't settle in. The Polish community wouldn't talk to her because she had a Jewish husband and the Jewish community wouldn't talk to him because he had a Polish wife. As a result they returned to Poland and then moved to Germany, where they live to this day.

We didn't observe any religious rituals at home. Grandma Pikielny's was the only place we had some contact with the Jewish traditions. We had holiday dinners there. Although my father was the eldest it was usually his brother Maks who led the prayers. Alek, his son, was a year older than me and had had a bar mitzvah. I didn't have one, because in October it was already war. I guess if I'd been supposed to have one I would've had to be prepared for it earlier, and there'd been none of that. I did have Jewish religion classes at school though, because they were compulsory.

I knew we were Jews. I felt it was a strange thing to be. During a stay at the Rabka sanatorium I shared a room with a boy and I told him I was Jewish. I don't recall having any trouble because of that. I didn't speak of it the next time I was there, though. During another stay, I don't remember what year it was, I met a boy, older than me. His father was an officer of some kind, or maybe even the deputy mayor of Warsaw. The boy told me the Germans would do us [Poles] no harm, and if war broke out, we would win it of course, and we would drop Jewish heads on Berlin from airplanes. Such were the moods at the time.

A seamstress used to come to our house sometimes. She lived somewhere near Lodz. She was German and a Baptist. She wouldn't refer to Hitler by any name other than 'the Antichrist.' She had a son, older than me, who used to come and teach me carpentry, because I had a carpenter's workbench at home, which I 'inherited' from Uncle Lolek. When the war broke out it turned out the Baptist youth organizations were part of the Hitlerjugend 16.

In 1937 I went to Sopot [Sopot was part of the Free City of Danzig] 17 for the summer vacation, with a friend of a friend of my mother's to take care of me. I don't remember her name. There were lots of people at the beach who had flags with 'Hakenkreuze' [Ger.: swastikas]. They also organized a 'Blumenkorso' [Ger.: a sort of parade]. I remember a very pretty young woman riding a horse at the head of the procession. She had a 'Hakenkreuz' armband. I met that woman in Lodz after the holidays. There were no major anti-Jewish incidents at that time, just these demonstrations.

In 1938 we went to Orlow [now a district of Gdynia]. We went to Sopot to see the people we had stayed with a year earlier. They already had very few guests. Jews were only allowed to use the part of the beach right next to the toilets. It was an area the size of an average room. There were 'Juden verboten' [Ger.: Jews forbidden] signs everywhere.

In 1939 Lodz was taken in seven days. Following the order of Col. Umiastowski 18, men marched east. There was no military protection. Near Brzeziny [a town 10 km from Lodz], where the road was full of people, German planes would fly over and shoot at them with machine guns. There was no way through. My father went there as well, but seeing what was going on he returned to Lodz. There was a rumor my uncle Leon Szyfman was lying wounded in a ditch somewhere. My aunt went to look for him, but didn't find him. All that happened during those first couple of days. Later we lost touch with our family, except for my father's brother Henryk. My mother kept saying we ought to go east, do whatever it takes not to be under German rule. Both Grandpa and my father thought it was exaggerated out of all proportion, though, and that the Germans wouldn't do anything bad, because they're such a cultured nation. But Grandma Sara left, and so did Raja with her two little daughters, Niusia and Inia, and probably also Maks, my father's brother, with his wife and kids. They must have got stuck in the Warsaw ghetto.

In 1939 I was due to start gymnasium. But the Germans closed all the schools. They also banned Jews from crossing Piotrkowska Street, except at the two ends [Piotrkowska Street is Lodz's longest street, 4 km long]. Later there was a school in the ghetto for some time, but my parents wouldn't let me go there. I was home schooled.

At the end of November or early in December 1939 the Germans told us to leave our house. There were just the three of us at the time - Grandma, Mom, and me. Suddenly around twenty SS men in black uniforms and some Volksdeutsche 19 entered our apartment. We had two hours to leave it. We were only allowed to take with us what the Germans threw out of the closets onto the floor. It later turned out a German doctor took our apartment, one of those so-called 'Baltdeutsche' [people from the Baltic states who voluntarily accepted German citizenship]. There was an agreement between Germany and the Baltic states that the Germans from those countries would be resettled on the territory of the Reich. Lodz was part of the Reich...

Before the ghetto was closed my father decided to go to our apartment. He spoke with the German, I think the German let him take some tools. There'd always been a picture of me on my father's desk and it was still standing there after we'd moved out of the apartment. That stuck in my mind because it was incredible.

We spent a night at my classmate Rutka's parents'; they were neighbors from the house opposite. They were called Zylberberg. Later we moved to my uncle Henryk's parents-in-law, who lived in Lodz on Pomorska Street. They were called Mazo. My uncle and his family moved in as well, from Zdunska Wola [50 km south of Lodz].

At that time I became close friends with my cousin Romek and two non-Jewish girls living in the same house. One was older and the other younger than me. We wrote rhymes. I remember the first lines of one: 'On the third floor, by the sewer pipe, at the very top, live the Wysockis - quite a lot...,' I don't remember the rest of it. One of the girls wrote this rhyme: 'And that Mazo, that 'avant,' was such a bon vivant.' Those were still sort of carefree days. We stayed at that house until my father was assigned an apartment in the area it was already known would be in the ghetto. The address was 40 Zgierska Street.

We moved in in January 1940. It was a two-room apartment with a kitchen. The house had its own running water supply from a well. The house was connected to the mains sewage system. Those were luxurious conditions, considering the time and place. In Lodz there was running water and a sewage system downtown only, and not in every building at that. Unfortunately, the water-pipes stopped working in the winter of 1939/40 as there wasn't enough heating to keep the water running.

For some time three families occupied the apartment. Ours, Grandma and Grandpa, and the Zylberbergs we'd stayed with after being thrown out of our apartment. They lived in one of the rooms with their daughter, and I slept there, too, while my parents and grandparents lived in the other. They got an apartment afterwards and we stayed there. There were heating problems in the winter, so later we generally used only one room.

Grandma Drutowski died on 7th November 1940 and was buried in the cemetery on Bracka Street, the same one where we later buried Grandpa. Her funeral was my first exposure to the cemetery and the ceremonies. I don't recall any prayers being said. I remember how amazing the way people were buried seemed to me. The body is wrapped in a white shroud and put straight into the ground.

I already said my parents didn't let me go to the only school, which was on the other side of the ghetto. At first I went to my teacher's apartment. He tutored me through the gymnasium curriculum. Neither I nor Mom worked at that time. It was only later that we all had to have jobs to be safer. [Editor's note: having a job was protection from being deported from the ghetto.]

I started to work in a company collecting and recycling rags. It was 1941 I think. At that time Jews deported to the ghetto from the Sudety region [now the Czech Republic] had set up a workshop by the 'Sortierungs- und Verwertungshalle f. Abfälle' [Ger.: waste processing plant], producing artificial jewelry. These were brooches cut out of metal plates. I began to work with them. We spoke to each other in English, which I had apparently learned earlier, because we did somehow communicate. Later I worked at an electrical and mechanical workshop, 'Betrieb 39 Elektrotchn.-Abtlg.' [Ger.: Plant no. 39, Electrical and Mechanical Branch], repairing electric motors. I worked there until the ghetto liquidation. [Editor's note: when the Lodz ghetto was liquidated 80,000 people were sent to Auschwitz and about 800 stayed].

My mother worked in a workshop producing slippers, 'Hausschuh-Abtlg.' [Ger.: Slipper Branch]. The establishment was located on the ground floor of our house. It wasn't a particularly hard job, there was no harsh discipline enforced, Mom didn't have to go there at a particular time. All the workshops were registered and managed by the community administration [the Jewish Council]. We got wages and also ration cards, but I don't remember any shops. I think you could go to the baker's and ask for bread. You needed both the card and the money.

There was a black market in the ghetto but I remember going for coal and food to the other side of Zgierska Street. Zgierska Street was divided - both of the sidewalks and the houses were in the ghetto, but not the roadway. You crossed it using a footbridge. All of the food was transported via Zgierska. The staples were rutabaga and kale. Mom also started to make chulent. Before the war I didn't know such a dish existed. In the ghetto it had the advantage that you gave it to the baker on Friday and took it back ready to eat on Saturday.

In the workshop where I was employed most of the workers were intellectual youth, mostly leftist. Leftist ideas were attractive at the time, because they promised to solve all the problems which had led to us being in a ghetto and which we'd been more or less aware of before the war. I hadn't experienced anti-Semitism personally but I'd started to read the papers before the war and knew what was happening.

I soaked up those left-wing ideas in the ghetto. We arrived at work one morning and they wouldn't let us in. Apparently something was missing and they wouldn't let us in until it was found. After some time they pointed to the ones who could go in and the ones who could not. We told them none of us had stolen anything and there was no reason for some of us to be let in and some not. And so the fuss started, we were accused of mutiny and they wanted to fire us. That could be dangerous, because you had to work somewhere. I didn't tell anyone at home, especially in view of my father, who had typhoid fever, and I left home every morning as if nothing had happened. One of the foremen, a turner called Kolerszejn, accused us of propagating communist ideas, which according to him was unacceptable. Finally the argument was settled and we went back to work.

There was an underground youth organization in the ghetto 20. I was not a member myself but I did co-operate with its members. It was a conspiratorial group operating around the workshops I worked in. The group consisted mainly of young people, whose task was to spread leftist ideas and distribute the works of the Marxist classics [Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx, Rosa Luxemburg]. I know the organization had contacts with other such groups outside the ghetto. Thanks to that they had information on camps such as Chelmno 21 or Auschwitz. At some point they tried to spread that knowledge among the ghetto inhabitants. It wasn't perceived as credible, though. It's psychologically justified to some extent, that people wouldn't exactly embrace the news that their relatives were being killed or had already been killed.

The Germans, while preparing the liquidation of the ghetto, launched a special propaganda campaign, wanted to calm us. They tried to make us believe we were to be transported to another town, where we would carry on working. They encouraged us to take along everything we needed.

During the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto some 800 people were given the task of clearing the area. Some people went into hiding. Most of them were found. I know a tragic story, which I learned about a relatively short time ago from Dr. Mostowicz 22. Three young men were in a hideout and one of them caught typhoid. He had a very high fever. The others killed him, fearing his moans would lead to the discovery of their hideout. I knew the parents of the dead man, because his father was a doctor as well. They survived the war.

We stayed in the ghetto until the very end [August 1944]. Doctors were the last group to be deported. We were transported to Auschwitz in cattle cars, loaded in the morning. We saw Polish railroad workers along the way gesturing at us that we were heading for death. We reached the destination in about 24 hours, before dawn.

As we reached the ramp in Auschwitz-Birkenau we were told to leave everything in the cars. Men and women were separated. Afterwards both groups went through a selection, conducted by three or four SS men. They judged by people's appearance if they were fit to work. Both my father and I passed the selection. It later turned out Mom did, too. My father found that out when he started carting trash in Auschwitz, because people with a university degree were given that job. I was assigned to a different block.

They soon started to 'buy,' as it used to be called at the time, metalworkers [they were needed to work in the German workshops] in that block. They carried out a selection among those claiming to be metalworkers. The ones looking fit were picked out and sent to a different labor camp. You had to take off all your clothes.

I met a friend then, Bialer, who worked with me in the ghetto and was a member of the organization I spoke of. We started to hang out together and we were both 'bought,' to go to the AL Friedland camp [a subcamp of Gross Rosen] 23, where 500 people were transported. That was a place designed primarily as a labor camp. The conditions were rather harsh. Some of us went straight for factory training.

We worked in a plant owned by VDM, I think it was called Hermann Goering Werke, which manufactured plane propellers, and we also did some earthworks, or 'Stollenbau' [Ger.]. We dug large recesses in the slopes; I still don't know what they were for. It was a very hard job, the mountains were rocky and we had no special tools. We had a German foreman, an old man, who was rather decent but had no influence whatsoever. We were guarded by SS men, Germans, but also Ukrainians and Latvians, who were often worse than the Germans.

When the Soviet offensive reached Silesia, the death marches 24 began, which of course weren't called that at the time. All the camps were being moved further west. The people marched on foot, and had to stay somewhere for the nights. Our camp was one such place, along with the nearby unused Hitlerjugend camp.

On one such occasion, when I was lying ill in the infirmary, some fellow inmates rushed in to tell me my father was among the newly arrived. I asked the doctor, a Slovak, to let my father see me. He came and stayed with me overnight. Unfortunately, next morning he had to return to the group he'd come with from the camp in Kaltwasser [now Zimna Wódka]. In the middle of March 1945 he died in Flossenburg camp 25. He was probably killed.

A man called Abram Kajzer kept a diary during his stay at Kaltwasser camp and particularly during the march. He hid his notes in toilets. After the war he traveled the whole route again and collected them all. He wrote in Yiddish, because he didn't speak Polish, but in 1947 he asked Adam Ostoja of the Wydawnictwo Lodzkie publishing house to help him with the translation. The book was translated and published under the title 'Za drutami smierci' ['Behind the Wires of Death,' edited and prefaced by Adam Ostoja, Wydawnictwo Lodzkie 1962]. Kajzer wrote of being in Zimna with my father. He had fond memories of him.

Shortly after my meeting with my father I had an accident at work. A milling cutter injured two fingers on my left hand. The wounds wouldn't heal throughout the war, mainly because of malnutrition. Consequently, I was unable to work at all. It was sometime in March or April. I have some doubts regarding the exact date as we had no sense of time in the camp. We just knew if it was winter or spring.

Anyway, I spent the rest of the time in the infirmary. I came outside one day to chat with some friends. Suddenly someone came running to fetch me, as they were looking for me in the infirmary. I entered the room and saw all the patients standing naked before some Germans. One of them, uniformed, was collecting all the patients' charts. Behind him stood our 'Lagerältester' [Ger.: a prisoner in charge of all the others in the camp], a Jew from Lodz called Herszkom, and he gestured me to drop my chart on the floor and cover it with my clothes. So I did and stood naked, too. As soon as the Germans made sure they got all the charts, they left. A couple of days later a truck came and took all the people they'd taken away the charts from. I stayed. I guess Herszkom saved my life.

On 8th May 1945 at noon the SS guards ordered a roll-call. The weather was beautiful. The commandant of the Friedland camp, a captain, I think, said they were leaving, but not for long, and so they were leaving us there. They would know how we'd behaved as they returned. If we misbehaved, they'd punish us. A member of the German citizens' committee which had assembled in Friedland spoke next. He spoke in a different tone. He asked us not to leave the camp, so that we'd all be handed over to the Soviet authorities together. We were asked if we held any grudges against the leaving SS crew.

In the morning of 9th May it turned out the members of the committee had fled; the camp was situated next to a road leading to the town. We concluded we had to hide as well, because otherwise the retreating German troops could kill us. We ran uphill, into the woods. There were uniformed Germans there, very close to us, firing machine guns at the advancing Soviet troops. Later the German units moved away and the Soviets marched in.

That's how I made it through till 9th May. When the Russians entered, my friend Jakub Litwin and I left the camp. We had our camp clothes on. We were infested with lice. And in that state we went to the town next to our camp. It was called Friedland, currently Mieroszow [95 km from Wroclaw]. The town was already partially deserted, because the Germans had started to leave somewhat earlier. We found ourselves in a German woman's apartment, who welcomed us with open arms, although she hadn't been all that friendly towards us at the factory, where she'd worked as a nurse. We burned our clothes and took a bath.

We left her place the next day and eventually settled in the guards' room at the linen factory. A coachman working there lived in a two-story house by the gates. There was a room for the guards on the second floor, with a couple of beds. My friend Jakub and I moved in and dined downstairs. The coachman's wife cooked and we provided the supplies, which meant going over to the Soviet army cooks and asking them to give us something.

We became friends with a Tajik from the Soviet troops. I honestly don't know how we managed to communicate. He was a very nice guy. He asked us to pay him a visit, said if we came we would do nothing but lie back and eat water melons.

Soon Jakub's brother somehow learned of his lot and sent a car for him. Jakub was later to get a degree and become a professor of philosophy. He died of Alzheimer's five years ago. I was left alone. I heard my mother was in Lodz. It was May or June. So I went to Lodz and met my mother, but I don't remember how that was possible as I didn't know her address after all. Mom was staying with some relatives, who'd been in the Warsaw ghetto and later on the so-called 'Aryan side.' Because I didn't have a place to stay in Lodz, after a few days I returned to Friedland.

When she returned to Lodz, Mom went to our pre-war apartment, but the people who occupied it wouldn't even let her in. Mom filed a lawsuit and sent for me only after getting a court order that she was to get three rooms in the apartment. I came to Lodz sometime in August.

Mom started to work as a secretary in the Health Protection Society [TOZ]. Later she got a job at a textile industry export center, because she knew three languages - English, German, and French. She got married for the second time. She took her second husband's last name - Tikitin. My step- father was a doctor, Mom met him at the TOZ. She died in 1972.

After my return to Lodz I began to work at the Widzewska Manufaktura factory as an electrical mechanic. I enrolled in a school for adults. I went in at the fourth grade of gymnasium. I passed the lowers [Pol: mala matura] first and then the higher standard exams. [Editor's note: in the regular school system, examinations taken at age 16 and 18, respectively. The latter are school-leaving examinations at pre-university level]. I decided to become an electrical engineer. After graduating from school I moved with a schoolmate to Gdansk.

I began my studies at Gdansk Technical University in 1947. That's where I met my wife, Nina. Nina was born in 1930 in Warsaw, where she lived until the war. She did an engineering course, then a master's degree, then a PhD and a postdoctoral degree. The University of Helsinki awarded her a honorary doctorate.

My wife's brother was called Mieczyslaw. He was born in 1923 in Siedlice. He was a painter. He died in 2002 in Sopot. He had a wife, Eleonora, nee Jagaciak, and two children: Malgorzata and Mikolaj.

After graduation I lectured at Gdansk Technical University. I started a PhD at Warsaw Technical University. I never finished it. From 1956 until my retirement I worked in the Industrial Telecommunications Institute. Our son was born in 1953. He graduated from the Popular Music Department in Katowice. He has a son, Jakub.

My upbringing, but also my wartime experiences have made me a man who unequivocally declares not to believe in God. I think if God was truly the one to take care of justice, then what I've seen - and I'm not even speaking of what I've come through myself - cannot have been punishment for any kind of sins. And babies have nothing to be punished for. But in the Lodz ghetto the Germans would drop babies from the third floor straight onto the back of a truck, arrange them into an even layer, and then trample on them and lay a second layer... It's impossible to still have faith.

I didn't and still don't have any contact with the Jewish traditions. I'm a member of the Jewish Veterans and World War Two Victims Association 23, but that's an absolutely non-religious organization. I had a feeling I ought to get involved in social work, it's a kind of obligation that older people feel towards the young. I agreed to take part in the work of a welfare committee. That committee consists of representatives of various Jewish organizations. Recently I even joined the Association's Central Board.

I don't have any Jewish friends in Poland. I don't know if that's good or bad. Or what others think of it, either. I don't think only religious people can be Jewish, but maybe that is so to some degree.

Glossary: