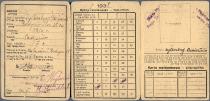

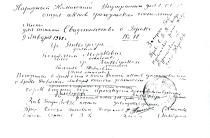

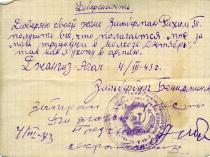

I have preserved this document since the war. This was issued by kolkhoz ‘Ekenchi Beshaldyk’ in Dzhangiz -Agach for my wife Rachela Zylberberg in 1943

I arrived in Gorky sometime in January - February 1942. At that point General Anders was organizing his army and I decided to join it. We were sent to Kuybyshev. I remember that several hundred of us slept on the station forecourt floor there, and the chaplain, Bishop Gawlina, brought us food.

A few weeks later smaller groups were organized and I and a group of about ten people went to Alma Ata, the capital of Kazakhstan, to the recruiting commission. The commission comprised two colonels, a Pole and a Russian. The Pole, when he heard that I had been stripped of my civil rights for ten years before 1939, quickly calculated the years and said, 'This citizen was supposed to be inside until 1940, and it's from then that his sentence of suspension of civil rights commences. That means that until 1950 this citizen has no rights in our country.' A repeat of what had happened in 1939. The other colonel, a Russian, didn't understand a word of Polish, but he was sure of one thing: I was not to be trusted. I was sent straight from there, under escort, to a coal mine in Karaganda.

That was my second camp. There were Russians, Jews and Poles working there. It was a brown coal mine, opencast. We would hack lumps out with a pickaxe and load them onto the wagons by hand. Then the wagons went out over ground. The conditions in the mine were so harsh that we couldn't have lasted very long there. We lived in a dig-out, where it was so damp that you could get tuberculosis very quickly. I was saved from a serious case of typhus. I survived because I was taken to a hospital. I remember clearly that I had a fever of over 41 degrees. The treatment involved my being stripped naked and wrapped, without any drugs, in a cold, wet sheet. When it dried quickly, another sheet was ready, and that way they succeeded in bringing my temperature down. A few people survived in a similar way, but the rest snuffed it. The so-called doctor who looked after us said to me, 'You've the heart of a horse!' When I came out of hospital I was in no state to go back to the mine. And from there I went to a place called Dzhangiz-Agach, not far from Alma Ata, to a kolkhoz called Ekenchi Beshaldyk, which in Kazakh means 'The Second Five-Year Plan.' My wife and some friends from our town were there.