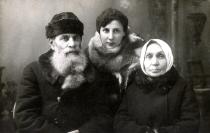

This is me and my family, I am on the right, next to me is my father Aron Deich, my brother Samuel Deich and my mother Rivka Deich. The picture was taken in a photo shop in Kiev in 1947 on the occasion of Samuel's departure to study in Leningrad.

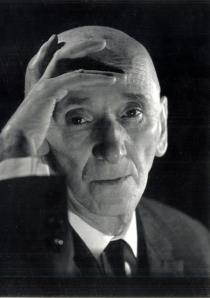

In the late 1940s the policy of formalism and cosmopolitism began [the campaign against 'cosmopolitans']. It was actually a form of state anti-Semitism. I was very naive, and at first I couldn't believe that an individual could be destroyed because he wasn't Russian or Ukrainian. Our teacher, Boris Liatoshynskiy, an outstanding composer and not Jewish, was among the first victims of the policy. He was fired and defamed. He was absurdly accused of formalism. Party activists called lyrical works that didn't openly call for the victory of communist ideas all over the world, formalism. This was why they destroyed talented people and replace them with whoever.

My father also felt the impact of the campaign. He was the head of a department at the Chamber of Commerce of the Art Fund. Akapian, the manager of the Chamber of Commerce, highly valued my father. When he was absurdly accused of not showing enough enthusiasm in the struggle for the ideals of communism, Akapian tried to defend him. He wrote letters to the party authorities, but it didn't help. My father was fired on the orders of the party authorities. He went to a high party official in Moscow to seek help. He was reinstated at work but not for long. Within some time he was fired again. He realized that he wouldn't be reinstated again. He found a job in a small office in Podol. My father was responsible for a department and successful at work.

In 1947 my brother received an invitation from his teacher Isaiah Bawler and left the Conservatory in Kiev to go to Leningrad. Samuel received a Stalin-stipend, a special scholarship that was only given to the best students. He graduated from two faculties: piano and organ. Later he also graduated from the post-graduate organ course.

In the same year, when I was a 5th-year student, my teacher took me to work in the evening music school which people called 'Conservatory for Workers'. This was the only school in Kiev where students, who worked during the day, could study in the evening. There were representatives of all layers of society, from the children of collective farmers to the grandson of a professor. Students had to pay a reasonable fee for their studies. It was very cold in the classrooms, and in winter we kept our coats on. Students had kerosene lamps and candles with them, since the light went out continuously. I worked at the school for 15 years. The students there were very inspired.