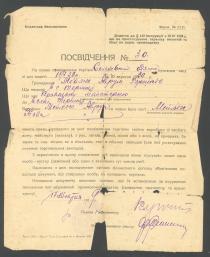

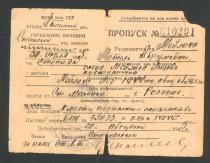

This is the pass permitting me to travel from Stepnyak, where I was in exile, to the town of Rossosh, where I won the contest for the position of history teacher in the institute. Without such a pass it was impossible to move anywhere in the war years - they just wouldn't sell you railway tickets. To obtain this permit, my wife's father had to bribe the chief of militia by way of giving him a live ram. The ram was earned by my father-in-law by repairing a separator for the collective farm. In acknowledgement a local Kazakh brought this ram on his horse directly to our place, and I took the animal to the chief of militia. The chief wrote out this pass for me right away. Such was the bribe story.

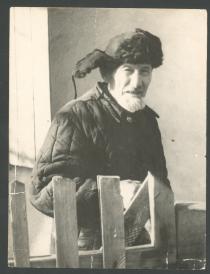

In Stepnyak I was friends with Kazakhs, Russians, Ukrainians and Germans, who were deported there. There was a Jewish family of the director of the Mechanical Factory. Certainly, I didn’t try to get acquainted with or visit him. He could be compromised by such an acquaintance. He was a good man, and he was also arrested during the so-called Doctors’ Plot investigation. But he was quickly released, because workers respected him a great deal. When he was arrested, the workers, about 100 of them, tried to defend him as much as they could. And they succeeded. After the war I was on very good terms with the inhabitants of Stepnyak. And when we were leaving, they went out to see us off and were very sorry that we were moving away, and we were sorry, too. The attitude towards us was most friendly. I remember with gratitude the Russians, Ukrainians and Kazakhs.

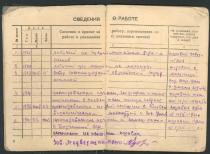

In Rossosh I worked from 1945 until 1949. I lectured on the history of the Ancient World and Middle Ages at the Teachers Institute. It was there that I defended my doctor’s thesis ‘Entry of Italy into the First World War.’ In 1949 a commission from the regional party committee arrived and they attended my lectures together with the pro-rector Efremov, a remarkable man. After lectures they told Efremov that they were very pleased with my lectures. And at a meeting in the institute they declared that I advocated cosmopolitan ideas at my lectures, and demanded that I be dismissed. Nobody of the institute’s staff supported them. I decided to resign in order not to let anybody down, and return to Stepnyak.

At night two militiamen took me to the state security building, the KGB, where I was interrogated, and during the interrogation a guard comes in and says, ‘There are some people there that want to talk to you.’ The guard remained with me, and the chief of the KGB went out to these people. He returned in ten minutes and asked, ‘What shall I do with you?’ I was surprised to hear such a question and said, ‘Give me an opportunity to take my family, my wife and two small children to her parents.’ He answered, ‘I’ll do that, but you promise to leave in the morning!’ It turned out, those were my students who came and asked not to let me go away…. But he released me, and I left that very day. It was the only time when I was persecuted and dismissed as a cosmopolitan. I never had any conflicts whatsoever for being a Jew.