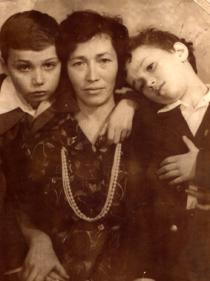

I, Lubov Rozenfeld with my sons Vladimir Matvienko (left) and Mikhail Matvienko. I decided to be photographed with them for the memory on the occasion of the end of an academic year. Signed on the backside: '1977. Misha - in the 1st form, Vova - in the 3rd form.'. Kiev, 1977.

I got married at the age of 28. I wouldn't say it was for love. My husband Vasiliy Matvienko, a Ukrainian man, was my student. I worked as a tutor in a vocational school: there were about 100 boys and adults under my tutorship. He came to school after the army and was a little younger than me. He helped me a lot: he gave orders to other guys and I felt comfortable with his input. In the evening my students accompanied me home: it was dangerous to go alone. At first there were 6 guys, then four, then two and then there was only Vasiliy left, and finally I got married … my mother didn't mind. We registered our marriage in a registry office. There were no celebrations. We bought a cake and had tea in the kitchen with my mother in the evening. We lived in our room in Kreschatitskiy Lane. Vasiliy learned the profession of a mechanic at school and later became a mechanic of the 6th category. He played the accordion well and I helped him to enter a music school. He finished it and often played at weddings or other celebrations. He was very talented, kind and loved me.

On 24 July 1967 our older son was born. I talked Vasiliy into naming our son Vladimir. I love my cousin brother Vladimir Rozenstein and wanted to name my son after him. Our younger son was born on 26 August 1970. I named him Mikhail after my father. I've never been religious, but it happened so that my older son was born on St. Vladimir Day by the Christian calendar and I named him Vladimir, and Mikhail was born on the day of St. Michael and I named him Mikhail. I had to leave Vasiliy, hen my younger son was 2. We were different, and besides, he drank and was terribly jealous. My husband never supported me or the children. We lived from one payday to another, but we didn't do that bad. The children had clothes and sufficient food. In summer they went to pioneer camps. I didn't dream about a car, new furniture or a vacation. We could only afford vitally important things.

My sons are very different like day and night. Vladimir didn't like school: I sent him to a music school to study playing the violin. He studied 5 years and quit. Then he learned to play the clarinet for 3 years. His teacher said he produced excellent sound, but he quit. Now he plays every now and then whatever is at hand. After finishing the 8th form he entered the technical school for treatment of metal with cutting. He is very talented: he draws well, but he never displays his works. He makes sculptures, and he is very artistic. When he mimics somebody it's very funny, but he takes no advantage of his talents. All he wants is to be like everybody else.

My younger son Mikhail is very different: he is lively and active. I taught my sons to ski and skate. Vladimir preferred to sit on a bench, but Mikhail enjoyed skating. He is also talented. He also learned to play the violin. His teacher said: 'He is a born musician'. He is an improviser by nature; it's hard for him to play by notes. He can also play the piano.

I worked as a tutor in the children's department of the railroad hospital for many years. There were 80 children under my tutorship. I arranged morning concerts for them, played the piano and the children performed. When my mother passed away I went to work for a private company since my salary wasn't enough to even pay my apartment fee. I've written essays, my thoughts and considerations. I've never shown them to anyone, but I believed that one day there will be readers.

I remain an atheist. Those who have shot children shot my hypothetical faith in God. If God is powerful and merciful, he shouldn't allow this. Somebody wise said: 'believers have no questions, they just believe, but atheists get no answers'. I've got no answers to my questions. There is no excuse to murder of children - children cannot be guilty.