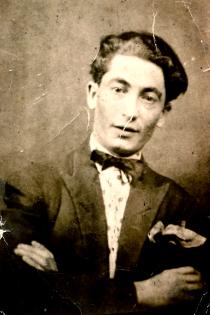

This is my father, Lazar Goldstein, before being drafted to the Romanian army, next to him is an upholsterer friend named Iancu. My father is the one on the left. Although the setting looks like the interior of a house, the photo was actually taken at a photo cabinet in the Jewish quarter of Dudesti. Iancu was one of my father's co-workers. My father was an apolitical man par excellence. He didn't read the newspapers, didn't comment on politics and wasn't interested in it. He remained the same pedantic individual, the same distinguished man who would spend one hour in front of the mirror every day before going to work. He used to shave every morning.

My father's only education consisted of four elementary grades, as he had to start earning his living at an early age. He left his home at about 18 and ended up in Buhcarest. I don't know who taught him carpentry, but he was very skilled. He owned a workshop in Bucharest, where he had two apprentices. He was very industrious and persevering and valued a thing that was well crafted. He made the pieces of furniture all the way from the beginning to the end. He often worked for important people, like the writer Liviu Rebreanu [Liviu Rebreanu (1885-1944): Romanian prose writer and playwright, author of significant social novels such as Ion, Rascoala - The Uprising -, and Padurea spanzuratilor - The Forest of the Hanged.] or the prominent politician Armand Calinescu [Armand Calinescu (1893-1939): president of the Ministers' Council, an anti-Nazi and anti-Legionary figure, advocate of the alliance with France and England; he had the courage to tell King Carol II, in 1939, that ?the Germans are a danger and an alliance with them equals a protectorate?. He was assassinated by the Legionaries on 21st September 1939, in Bucharest.].

The house and the workshop were in fact one and the same thing, and my mother would get upset because the house was full of sawdust. My father would have liked all the family to help him in his work, as the two apprentices weren't always there. I used to help him pretty often. Although I was only 10, I was familiar with timber and I enjoyed the smell of new furniture. My job was to polish the furniture. It was no easy job, for, if my arm got tired, I had to quickly remove the brush imbued with chemical substances from the piece of furniture, lest it should imprint itself and burn the material.

At a certain point, my father lost the workshop, because he didn't manage to pay his taxes. So one beautiful spring day, some people from the police and the city hall came. They were beating this huge drum, reading aloud the decision that empowered them to take my father's workshop away from him. It was a scene worthy of the Middle Ages. After that, my father became a free-lance worker. He would usually go to his customers' places.

He died at the age of 63, in 1963, and was buried at the cemetery on Giurgiului St., according to the Jewish ritual. We observed the Yahrzeit, and the one who recited the Kaddish was my brother.