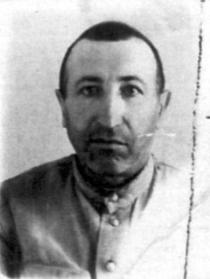

This is my brother Jacob Kipnis, standing, photographed with his fellow comrade in the Far East in 1940.

My brother became a member of the Communist Party in 1935 when he worked at the plant. The regional party committee appointed him as chairman of the ‘selpo’ – village trade association, network grocery of shops. He was also secretary of the party unit of the village and took part in dispossession of farmers. Someone even shot his gun at him one night, but only injured his arm.

In 1935 my brother was fired and expelled from the Party. Someone reported on him – he was falsely accused of dishonesty and bribing. An anonymous letter was enough at that time to accuse a person and fire him from work. There was no way to prove that you were innocent.

Shortly afterward he was recruited to the army and sent to serve in the Far East. My brother didn’t agree with his being expelled from the Party and wrote requests to the central committee of the Communist Party in Moscow. He was restored in the Party.

My mother begged him to return and I joined her in this urge. He demobilized and returned home at the end of 1940. He became a human resources inspector at the human resources department in Korosten. In March 1941 the military registry office sent him to take a training course in coding in Lutsk.

That was where he was when the war began. All cadets were given the rank of lieutenant and sent to the front. He was appointed to the railroad troops and retreated with them to Korosten. When he reached Korosten he ran home, but the house was locked – we had left it. He took a small pillow for the memory – it was called ‘dumka’ [thought] – that our mother had embroidered and left.

Shortly afterward the Germans occupied Malin and Korosten. My brother and 15 soldiers and officers of his military unit were captured by the Germans. They were locked in a wooden shed and there was a German guard near the shed. The shed had no foundation.

The officers tore off their straps so that the Germans couldn’t recognize their rank in case the Germans took them to interrogation in the morning and all captives began to dig a sap throwing the soil inside the shed to keep their plan secret from the Germans. When the sap was ready a few of them got outside and stabbed the guard with that same knife that they had used to make a sap.

All of them escaped, but only five of them managed to get to the Soviet troops. They went through the woods and all their food was what they could get in the forest: mainly these were berries. Jacob and our other militaries covered a distance of over 400 kilometers. They reached Chernigov where there was a sanitary train where my cousin Bronia was a medical nurse. She saw my brother in town by chance. She told us this story after the war.

This was the last information about my brother. He didn’t return from the war. Around 1947 we received a notification that he was missing. On the basis of this certificate my mother got an addition of a few rubles to her pension.