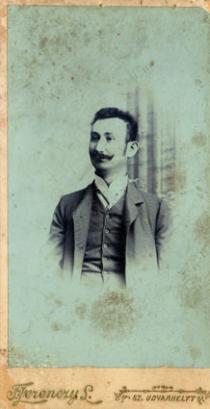

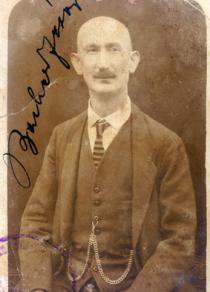

This is my father. I don’t know when this photo was taken, anyway, he’s not so young on this photo.

My father had a gold watch, but he didn’t really wear that. He was very modern, he visited Vienna, and saw wrist-watches there, so he had a wrist-watch too. He had a wrist-watch, not like this one, though this was wonderful. You can see it on the picture, it has a long watch-chain. I still have the watch-chain my father wears on this photo. My poor father died, then mammy divided it in three: she gave one part to her daughter-in-law, to my father’s wife, she gave one piece to me, and she kept one for herself. Ours got where the others, we had to surrender them. After my brother was taken to Ukraine, my husband was taken to Ukraine, mammy lived alone in Toplica, she didn’t live in Marosvasarhely. But she brought to Marosvasarhely her jewels, and they [the authorities] didn’t know her [so what kind of jewels she owned], and I could hide some of them. Like this one. I found it, because I had put it in a bottle, and I had buried it in my garden, that’s how I found it.

Not far from Gyergyovarhegy, about five kilometers far from where grandpa lived there was a huge timber mill with 6 frame-saws. The factory was installed in Gyegyovarhegy and Toplica. These two locations are quite close to each other. It takes half an hour by train. The one in Toplica was a large factory, with a few hundreds of workers, and if we take into account the employees working in the forest, it had a few thousands. The factory in Gyegyovarhegy had 6 log frames, the one in Toplica had 12 log frames and 12 saws. It had a few thousands of employees. At the beginning papa was cashier in Gyergyovarhegy. Well, it was close, and I don't know how, but he met mammy, who married him. Perhaps there was a cultural performance on May 10th, and perhaps the office-holders were invited and they went to see it. Mammy couldn't be more than twenty years old. They had a religious wedding surely, because there were many Jews in Gyergyoszentmiklos. Mammy lived in Gyergyovarhegy. I think they lived there for two years, dad was cashier there, and he got promoted, so they moved then to Toplica. When the director saw that my father was very good in his profession - actually he was a mathematical genius - he became a factory manager. The factory had two directors: a technical and an administrative director. My father was the technical director. He had a secure job and a great salary. He was the expert.

Dad didn't go to the synagogue on Sabbath, he had to go to the office. My mother didn't go to the synagogue on Sabbath, only on high holidays: at Pesach and at Yom Kippur. Sometimes I entered the synagogue for one hour or two. For example there was a synagogue in Toplica. But dad rented a large room, where the Banffy baths are today, I think it's transformed into a restaurant now. In the autumn, when we had holidays, dad rented it, I think on his own expenses, and they celebrated there, because there were many Jewish workers at the enterprise. There were at least 30-35 Jewish families there. And all the men went to the synagogue, and women too, but in a separate room. They had a Torah, he sent for a chazzan, they had everything. The room had glass above, like a glass door let's say, and it was open, so the chazzan's prayer was audible. And in the women's room tables and chairs were installed, that was the custom in villages. Before praying we all took breakfast. I don't know what the procedure is in the very observant communities, but we took breakfast. We went there with mammy. Mammy went up at nine o'clock, me at ten, half past ten and at one, at half past one it was over, and we left. We walked there, anyway this was the single way. And after that we had lunch, then we rested. Dad didn't go to the office at high holidays, at Shavuot and Yom Kippur.

Before school, I couldn't read and write yet, but my father taught me the French and the Hungarian cards. And how to play dominoes and chess. And it's also due to my father that I know the Hungarian history. He was a great Hungarian patriot. He brought me toys related to the Hungarian history. When he heard the Hungarian national anthem at the radio at noon - we didn't have television yet -, his tears were always flowing. The national anthem was always at noon. He was always a reader, he talked politics, and so he was aware of politics. My father was always a great admirer of Kossuth, therefore he brought me toys, for example a pack of cards with thirty-forty pieces, with questions related to history. When was the Battle of Mohacs? What does the Golden Bull mean? Things like this, and the answers were on the back. I had to learn all these, and from time to time he asked me the questions. My mother gave me books fit to my age. We had such a library, one could transform it into a public one. I read the newspaper since then, I order the newspapers even today. So I had a middle-class family.